Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: NHB Drama Games

- Sprache: Englisch

101 great drama games for use in any classroom or workshop setting. Part of the Nick Hern Books Drama Games series. A dip-in, flick-through, quick-fire resource book, packed with 101 lively drama games suitable for players of all ages, with many appropriate for children from age 6 upwards. Whilst aimed primarily at school, youth theatre and community groups, they are equally fun - and instructional - for adults to play in workshop or rehearsal settings. 'An extraordinarily helpful compendium... a valuable help to directors, teachers and workshop leaders' Max Stafford-Clark, from his Foreword

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 212

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Dedication

Foreword by Max Stafford-Clark

Introduction

Acknowledgements

Part One – WARM-UP

Body

1. Rubber Chicken!

2. Greyhound Race

3. MTV Cameraman

4. Super Shake

5. Mirror, Mirror…

6. Yes, Let’s!

7. The Incredible Itch

8. Daily-Routine Disco

9. Cat and Mouse

Face

10. Pass the Face

11. Ooey, Gooey, Chewy Gum

12. Funny Face

Voice

13. Boom-chicka-boom!

14. The Ultimate Tongue-Twisting Challenge

15. Radio Shuffle

16. Soundscapes

17. Human Orchestra

18. Good Evening, Your Majesty

19. Sing-along Word Association

Part Two – FAMILIARITY

20. Anyone Who…

21. Red Ball, Yellow Ball

22. Name Tag

23. The Amazing ‘A’s Game

24. Elbow to Elbow

25. I Love You, Honey!

Part Three – ENERGY

26. Energy Ball

27. Splat!

28. Whoosh!

29. Yeehah!

30. Duck, Duck, Goose!

31. Fruit Salad

32. Shark Attack!

33. Captain Cod

34. Penguin Race

35. King of the Jungle

36. Character Corners

Part Four – FOCUS

37. Mexican Clap

38. Eyes Up!

39. Cyclops

40. Zip, Zap, Zoom!

41. The Land of Back-to-Front

42. Go Bananas!

43. Relay Rhythms

44. Meddling Monkey

45. The Imaginatively Titled Yes-NoGame

46. Colombian Hypnosis

47. Liar, Liar!

48. Wink Murder

Part Five – TEAMWORK

49. Ring of Hands

50. Wolf and Sheep

51. Tableaux

52. 1. 2. 3. Washing Machine!

53. Picture Postcards

54. Star Wars

55. Enigma

56. Doctor, Doctor!

Part Six – TRUST

57. Friendly Follower

58. Leap of Faith

59. Falling Trees

Part Seven – CHARACTER

Introducing Characterisation

60. Family Portraits

61. Lead With Your…

62. Themed Musical Chairs

63. Grandma’s Hat

64. The Ministry of Funny Walks

65. Emotion Machines

66. Psychiatrist

67. Object Puppetry Challenge

Character Development

68. Pauper to Prince

69. Aces High!

70. Slingshot

71. Max’s Motivations

72. Character Hotseat

Part Eight – STORYTELLING

73. Wally’s Wallet

74. Super-sized Stories

75. Story Circle

76. Hilari-tales

77. The Great Guild of Archaeologists

78. Illustration Station

79. Living Newspapers

Part Nine – IMAGINATION

80. Super Chair

81. The Magical Mystery Box

82. No, Not Me!

83. Bomb and Shield

84. Word Wizard

85. Why Don’t We…

86. Alien Interview

87. Pantomime Race

Part Ten – IMPROVISATION

88. Speed Scene

89. Freeze!

90. Cocktail Party

91. One-Minute Wonder

92. Gossip Stream

93. Bus-stop Banter

94. Dramategories

95. Death by Chocolate

96. Rub-a-dub-dub

97. Sit, Stand, Lie Down

98. Instant Opera

Part Eleven – COOL-DOWN

99. Pressure Gauge

100. 20-1

101. Ring of Trust

Cross-Reference Index of Games

Skills

Practicalities

About the Author

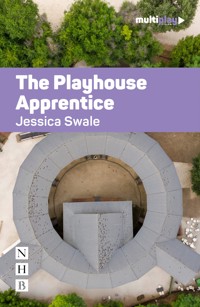

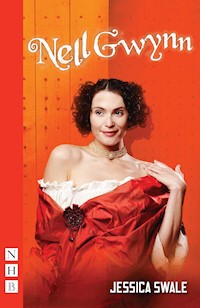

Other Titles in the Series

Copyright Information

For James, with love

FOREWORD

I know Jessica Swale as a conscientious, talented and intelligent, young director. She was my assistant on The Overwhelming, JT Rogers’ fine play that opened at the National Theatre in a National/Out of Joint co-production in early 2006. She was a warm, inventive and positive presence in the rehearsal room. The actors loved her. I was even more impressed when she started her own theatre company, Red Handed, shortly afterwards. It requires tenacity, vision and courage to start your own theatre company in these times.

In this book, she has written an extraordinarily helpful compendium and guide to drama games that will be a valuable help to directors, teachers and workshop leaders.

One of the strange anomalies of theatre is that ‘play’, ‘enjoyment’ and indeed ‘childishness’ is such an essential part of the rehearsal room, but we have to plan and work hard to attain it. The director must also then apply it. I recall clearly as a young director observing the rehearsals of a director who was slightly my senior. Her rehearsals were exuberant, inventive and original. But when I saw the eventual production that emerged from these rehearsals it contained very little of these qualities. We must structure and work for invention and spontaneity but we must then return to the text and apply it. The liveliness of the rehearsal room must inform the text.

Jessica’s book makes no claim to be either comprehensive or original. The games she lists are a stimulus to further invention and imagination: invent your own games. Her games have been pinched from everywhere. I recognised several of mine in there and in return I started making a list of games that I would pinch. I stopped when the list reached over twenty, and resolved to make the book a permanent assistant.

If you can’t get to a workshop run by Jessica Swale then invite her to your next party, whether it is for kids or adults. She will be of hilarious value!

Max Stafford-Clark

INTRODUCTION

Why Play?

To play needs much work. But when we experience the work as play, then it is not work any more.A play is play. Peter Brook

The concept of ‘play’ has been a foundation of theatrical tradition for many years, since Stanislavsky and his contemporaries incorporated exercises into rehearsals. Games are used in the pursuit of the soul of a character, to explore the ‘world of the play’ and to create dynamic relationships on stage. When used effectively, games can provide unparalleled opportunities for exploration and discovery. Whether working in a theatre company or in a school, in youth theatre or in outreach, they form an essential part of every modern practitioner’s toolkit.

The enduring popularity of drama games can be explained by the expansive range of skills that they develop in the participants. To actors, these exercises offer a lively means of exploring emotion, situation and character. For students, they provide an imaginative platform from which to jump, and in the community they offer a safe means of overcoming inhibitions and building relationships. Games can promote teamwork, spontaneity, confidence, trust and creativity, and many of them can be easily adapted to suit a range of workshop objectives. But how do you choose which to use? Where do you start and what are the challenges?

So often games are used as time-fillers by uninspired drama teachers who haven’t planned anything more structured to do. I remember the recurring feeling of disheartenment as a theatre-obsessed teenager, when, after playing Stuck in the Mud for half an hour, the drama teacher would utter the dreaded phrase, ‘We’ve got one hour left so… go off and make up a play.’ Such unstructured sessions may occasionally provide creative opportunities by accident, but they can hardly be classed as stimulating. Creating dynamic drama workshops is not difficult, it just requires forethought. Games must be carefully selected; each exercise should filter into the wider objectives of the lesson like a tributary into a river. A good facilitator uses games like bricks to build towards a specific outcome. Choose the wrong bricks, and the lesson crumbles.

Distinctions Between Drama and Theatre

Drama games can be as useful in a social or educational context as they are in the theatre. The activities in this book work equally well in both scenarios. Whilst, as a director, I have used many of these games in rehearsal, sometimes their most rewarding use has been in the classroom, where young and inexperienced students have surprised themselves with their own imaginative capacity.

The games arise from a variety of sources. Some have roots in traditional children’s games. However, it is vital to note that playground games and drama activities are not one and the same. Some forms of traditional play promote competitiveness and superiority. In contrast, whilst there is often room for individuality in drama, its primary aim is to develop collaboration as a form of creative learning. Drama is, in a sense, an extension of play, refining certain aspects of natural play whilst discouraging elements that are counterproductive in a creative environment, like egoism.

Positive skill-building is the foundation of ‘drama’ as an activity. This, in turn, is an ideal starting point for theatre-making. However, whether you want to extend your drama workshop towards the goal of performance is entirely your choice. Whilst theatre is a medium of performance created for the benefit of an audience, drama exists for the sake of its own participants. It is an active subject that uses theatrical values as a basis for creative engagement. This is a critical distinction to be made by those of us who work both as directors and workshop facilitators – it is all too easy to be unfair and demand great performances from workshop participants who simply want to ‘take part’ and gain social skills.

The Content of Your Workshop

The correct approach to workshop-leading has been a topic of debate for many years. Whether called a ‘workshop leader’, ‘director’, ‘teacher’, ‘difficultator’, ‘overseer’ or ‘side-coach’, the role of the drama facilitator is undeniably complex. As Joan Littlewood commented, ‘Chaos has to be very well organised.’

A well-run drama session can offer a creative springboard, a chance to escape into an imaginative realm, a means of making something visceral and exciting which, whilst temporal, is shared in that moment by the participants in the room. This is the joy of facilitating.

Whatever the educational goals of a workshop, be they theatrical, creative, social or academic, there are two essential aspects of a successful session:

1. The participants ought to feel that something has been achieved; they have created something, learned fresh concepts, gained skills or developed new bonds.

2. There must always be a sense of vitality and excitement. It is all too easy to lose sight of this in a quest to provide an informative experience.

You will undoubtedly find that, in an entertaining workshop, the students will absorb the material with ease. This explains why drama is now being used so frequently across the curriculum, and why issue-based theatre workshops are so popular in schools. As a young drama teacher, I was asked to teach Religious Studies in my free periods. I was hesitant to accept at first; however, I soon began to enjoy the challenge as I used drama to enliven the lessons. At the end of the year, my greatest concern was that other staff would think my students had cheated when final exam results revealed that every one scored over ninety per cent. But it was simply the use of drama as a kinaesthetic learning tool that helped them absorb the material so thoroughly – the story of John the Baptist as told on ‘J the B TV’ by a dynamic rapping trio certainly ensured every member of the class knew the tale inside out!

It is important to remember that there are no wrong answers in drama, and participants should not be discouraged for creating a ‘bad scene’. Of course, you can set parameters in order to improve technique, if your goals are theatrical, but always try and encourage participants to make improvements in a positive manner. ‘That was really dramatic, now try and turn to us a little more so that we don’t miss any of the exciting dialogue’ is far more encouraging than ‘Never have your backs to us when you are talking!’

In rehearsal, directors will be sure to find that the joy of playing often gives rise to creativity. I have often found the most original work with my theatre company, Red Handed, has sprung from game-filled rehearsals that allow the actors to experiment imaginatively with the text. Further, game-playing as a company allows a cooperative, creative spirit to develop that encourages greater collaboration. Whilst working with Max Stafford-Clark, I quickly learnt the benefit of using games throughout the rehearsal process to encourage actors to fully explore their roles. In early rehearsals he uses improvisation games to explore context and plot, then later exercises delve into the specifics of characterisation and objectives. His selective use of games encourages actors to work towards an incredible level of detail, that is electricfying in performance.

Safety and Welfare

The facilitator has certain basic responsibilities, regardless of the particular circumstances of their workshop. Hazard awareness must always be a primary concern. Always ensure that you arrive early enough to check the room for potential risks, and plan your workshop carefully according to the size of the space available. Think ahead about activities that include an element of risk. Trust exercises in particular, like Falling Trees (Game 59) or Leap of Faith (Game 58), ought to be used only when you know the participants well enough to trust them to undertake the exercises sensibly.

The facilitator must also take responsibility for the welfare of the participants. Non-actors will often be nervous about the level of public exposure they might be subject to. Confidence-building games are an ideal tool to encourage such hesitant participants. Attempt to structure each workshop so that participants work as a group before progressing to more demanding, creative activities in smaller teams or pairs. This allows the players to feel comfortable with each other before being put ‘in the spotlight’. A responsible facilitator will guide and encourage each participant through the creative process and watch carefully to ensure every individual is coping with the demands of the exercises.

The facilitator also has to be responsible for the emotional demands of the workshop, as acting so often entails the exploration of personal feelings. As theatre is a reflection of life, be aware that there can be participants who will have been affected by subjects in the drama. In asking the participants to share emotionally within the group, you are asking them to expose themselves in a manner that is unusual outside the theatre. In this context, the facilitator must be a supportive, caring coercer. Ensure you choose your activities carefully, in order to work at a level of emotional exploration appropriate for your group. You must remain aware that the process of making theatre is also about how to live, and about the sharing of values and ideals that should inform every rehearsal.

Bringing the Text to Life

The process of bringing the text to life – of drawing out the characters from the words – can often be challenging. Sometimes it is tempting to follow an intellectual approach, methodically deconstructing the text. However, this can deaden the work and result in actors becoming detached. Stanislavsky portentously warns that:

Intellectual analysis, if undertaken by itself and for its own sake, is harmful because its mathematical, dry qualities tend to chill an impulse of artistic élan and creative enthusiasm.

He suggests an artistic approach, as, ‘If the result of scholarly analysis is thought, the result of artistic analysis is feeling.’ But how does one attempt artistic analysis? Surely it must be an imaginative approach, a playful approach, without the binds of academic deconstruction. Certainly, games provide one of the greatest tools for exploring the text creatively. Several games in this book specifically provide methods for investigating the spoken word (see Part Seven: Character). Through investigating specific language choices, objectives and interpretation, the actors will undoubtedly find detail and intrigue in the text that may have previously gone unnoticed.

How to Use This Book

This book is designed as a dip-in, flick-through, quick-fire resource book that you can sling into your bag and pull out at an opportune moment. However, the material here is also suitable for planning entire workshops from start to finish. The book is divided into sections that enable you to see the specific focus of each game easily, allowing you to plan where it might be best suited in a workshop – handy warm-up games to start off, followed by skills tasks, extended exercises, and finally, cool-downs, in order to ensure the participants have time to reflect and recover from their active drama sessions!

After the summary of ‘How to Play’, you will often find suggestions for ‘Variations and Extensions’. The ‘Variations’ provide engaging alternatives to usual play, to allow you to use the game again in a different session with a new slant to capture the players’ imaginations. The ‘Extensions’ show ways to develop the games, to explore skills in more depth, to pursue ideas further in the development of scenarios, to to delve into historical or theatrical concepts that relate closely to the games, thereby extending players’ intellectual and physical skills. Many relate directly to the National Curriculum, for leaders using the games for GCSE or A-level groups.

Whilst the book is divided into sections according to the primary focus of each game, almost every game teaches multiple skills and could fit into a number of categories. For this reason, at the bottom of each page you will find a panel summarising the key aptitudes tested by the game. You will also find a suggested minimum age of the players. The age guide is meant merely as a handy tool for planning, to suggest games that are particularly suitable for younger players. It is by no means intended to exclude others. Having used most of these games with both actors and students, I have found that many assumed ‘children’s games’ can yield imaginative, and often hilarious, results when played with adults. One of the benefits of creative games is that many can be played at different levels according to the players. Games like Freeze! (Game 89) and Word Wizard (Game 84) are particular examples, and I have often had to insist vehemently that it was time to move on when adult actors simply wanted to go on playing King of the Jungle (Game 35)!

In the panel following each game, alongside the age recommendation and skills, you will find a suggestion of the group size. This is a rough estimation but some games work less well – or would even be dangerous – with an inappropriate number of players: Leap of Faith (Game 58) and Friendly Follower (Game 57), for example.

You will also find a suggested time period for each game, which will help you to plan the content of a workshop carefully. The time period suggested is the actual playing time, so if you are using an activity for the first time, be sure to add extra time for explaining the rules and having a practice round. I’m sure you will often find that an exercise yields interesting developments; so often, the best workshops are those that naturally develop in an unexpected direction as a consequence of participants’ spontaneity and creativity. Do ensure, for this reason, that you do not try to cram in too many activities, to avoid frustration and to allow time to pursue imaginative discoveries.

You will also find an indication of any ‘additional requirements’ in the panel at the foot of each page, which indicates any factors that need to be prepared in advance; the use of props, for instance, or the provision of music.

There are many factors to take into account when planning a workshop, and so you will find a cross-reference index at the back of this book. This will allow you to select games using other useful categories, such as the key skills developed, group size (games for pairs, solos, etc.), games that require preparation, games for advanced players, and games that initiate further creative opportunities.

Every game in this book has been tried and tested, adapted, reformed and reused. Some games are favourites with young children, others with foreign students and others with professional actors; one thing is for sure – many of these games can be equally creative when played with five or fifty-year-olds! The games come from all manner of sources, and I have collected and edited them over the years. I apologise if any appear to be ‘other people’s games’, but games, like the plots of plays, are continually shared, borrowed, adapted and recycled. I have attempted to collect as wide a range as possible and not to replicate, and you will no doubt recognise some games under different titles. I have tried to give credit where credit is due, but most are from the melting pot of resources that is shared in modern practice.

The Power of Play

Having worked as a teacher, director and educator, I have used these games in a host of contrasting scenarios. I shall give just one example of the potency of games to yield benefits; it is an example that truly reflects their capacity to initiate creativity, theatricality, personal skills and community.

In 2008 I was invited to work as a theatre director for Youth Bridge Global, a non-governmental organisation founded by Professor Andrew Garrod, that uses theatre in the developing world as a vehicle for imparting skills and bridging social gaps. I travelled to the Marshall Islands, a tiny developing nation in the North West Pacific Ocean, tasked with the challenge of directing a bilingual version of The Comedy of Errors in ten weeks, with a group of the islands’ high-school students. On arrival I was shocked by the limitations of their English-language skills, and, not being a natural linguist, began to sweat profusely at the daunting challenge of creating a theatre production – a Shakespeare production at that – without a shared vocabulary!

Many of the cast had no previous experience of drama as there is no local theatrical tradition on the islands. Even more surprising was the lack of texts available to read, in either in English or Marshallese, so the students’ literary skills were extremely limited. This was surely going to be a test of the power of drama, and workshop games specifically, to bridge the vast gap between the team of tutors and the actors. Daily rehearsals would soon reveal whether workshops could genuinely make an impact amongst disenfranchised youth. The islands suffer from an array of social problems, mainly brought about through poverty and reliance on foreign aid. Today, aid from the US accounts for over sixty per cent of the country’s GDP, making the Marshall Islands the most foreign-aid dependent nation in the world.

Living in a community with few openings for self-improvement, the young people were hungry for this opportunity to develop skills and ultimately improve employability. Over the following ten weeks, the benefits of using exercises daily with the cast became almost tangible. With a limited shared vocabulary, the language of drama – action, movement, expression, sound – became our means of communication. Easy warm-up games that necessitated little grasp of English (Mexican Clap, Game 37, for instance) immediately gave us some common ground. The simple aim of achieving a shared goal transcended any language barriers and soon the kids were all whooping and laughing as they broke their own time record. As sessions progressed we introduced more complex games (Star Wars, Game 54, for instance) in which they began to work cohesively as a team… and learn a little more about Western culture! By week four, they had mastered the art of Freeze! (Game 89), arriving at some stunning improvisation scenarios, having built confidence over the previous weeks with imaginative exercises like Super Chair (Game 80). Working in this manner, slowly increasing the complexity of the tasks, the students’ skills improved steadily. Further, their English vocabulary was expanding dramatically; much more quickly, I am ashamed to say, than my Marshallese.

Their final performances exceeded all my expectations and remain a testament to the power of drama to build confidence and community. The incredible transformation of the nervous, script-shy auditionees to the exuberant cast in performance is due mainly, I am sure, to the playful work we undertook together in rehearsal. Through working closely as a company, making discoveries together, we were able to share our experiences and create an event in which we had all invested. Over the final few nights, word of the cast’s success spread quickly and well over a thousand local people turned out, alongside the islands’ President and many other notable local dignitaries.

Whilst I am incredibly proud of their performances, the greatest outcome is that the cast are now planning an independent production for next year. This will be the first ever Marshallese-produced play, to my knowledge. They now feel empowered to step beyond our outsider-led project, having found the skills and confidence necessary to ‘go it alone’. This, surely, is the ultimate goal of every drama facilitator; to be able to step back and confidently say, ‘Now you don’t need me any more.’ The games this group played over the ten weeks promoted confidence, trust, team-building and empowerment, always underscored with a sense of fun. I am convinced that our communal game-playing is responsible for this most gratifying result, and I urge you to use these exercises positively to encourage your actors, whether they are professionals, students, members of the community – or Pacific Islanders.

I hope you enjoy playing these games as much as I do.

Jessica Swale

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I feel privileged to have shared in the plethora of activities that characterise contemporary drama and theatre practice. These provide the foundations for this book.

My own work and philosophy owes a great deal to Max Stafford-Clark, an inspiring director whose use of inventive games in rehearsal encourages a level of detail that is magnetising in performance. The writings of Augusto Boal, Peter Brook and Mike Alfreds continually reinforce my belief in the importance of ‘play’ in making plays. In education, Catherine Saker and Ron Price are responsible for proving to me how much fun a drama lesson could, and should, be. Further, I am indebted to Professor Andrew Garrod, founder of Youth Bridge Global, for the opportunity to experience drama’s remarkable capacity as a development tool.