Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Page to Stage study guides

- Sprache: Englisch

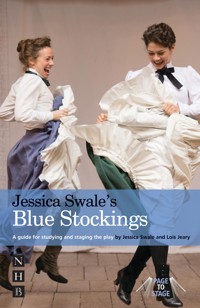

Jessica Swale's Blue Stockings is the empowering and surprising story of four young women fighting for their right to a university education in a world that assumed women belonged at home. First produced professionally at Shakespeare's Globe in 2013, and a sell-out success, it is now regularly performed by theatre groups in the UK and beyond, and widely studied by GCSE Drama students. This Page to Stage guide, written by the playwright, who also directed the first production at RADA, along with her assistant director Lois Jeary, is packed with contextual information, scene-by-scene and character breakdowns, and personal insights into the world of the play and the real lives that inspired it. An invaluable resource for those studying and staging the play, it takes you through the entire production process, considering each of the elements in turn, from sound and music to design and rehearsals. You'll also find notes from the original rehearsal process, extracts from working diaries, and interviews with key members of the creative team. Throughout, there are hints and tips on staging, and helpful games and exercises to bring the play to life on the stage and in the classroom. Highly accessible and uniquely authoritative, it is the indispensible guide for anyone studying, teaching or performing the play.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 295

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JESSICA SWALE’S

Blue Stockings

A Guide for Studying and Staging the Play

Jessica Swale and Lois Jeary

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

Blue Stockings in Rehearsal

The World of the Play

Character Profiles

Practical Scene Synopsis

Scene Timeline

Playing the Part

Staging Considerations

Staging Key Scenes

Blue Stockings in Production

Production History

Rehearsal Diary

Directing Perspectives

Scenic and Costume Design

Music

Character Study

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Glossary of Historical Figures

Endnotes

Page to Stage Series

About the Authors

Copyright Information

Introduction

ORIGINS

I never intended to write Blue Stockings. In fact, I never planned to be a writer at all. I thought that writers were middle-aged men with writing sheds and long beards. I live on a second floor, so have no shed, and thankfully no sign of a beard. But then something unexpected happened; I came across a nugget of history, an untold moment from the past, and that changed everything. I hadn’t been looking for a story, but one seemed to find me.

I was working as a theatre director with Max Stafford-Clark at Out of Joint, and was busy doing research for another play set in the 1800s. I was trying to work out what life was like for young Victorian women – what were their prospects, their hopes, their ambitions? In doing so, I stumbled upon the fact that most universities in England didn’t allow female students until the twentieth century. And, even worse, those that did tended to make life very difficult for those girls.

If you were a young woman at university in the late 1800s, your day might look something like this: you would walk a very long way from your out-of-town college to lectures, where you’d be mocked by both students and teachers, be forced to sit at the back, and have your work left unmarked or rejected. You would often be denied entry to your lectures because tutors would deem you a distraction or unworthy of their time. You would be humiliated in the street. And what’s more, because universities weren’t set up to accommodate women, you would have had great trouble going about your daily business. There were no toilets for women, so you may have had to carry a chamber pot with you, and hope to use it in a quiet street without being spotted. You may have been banned from the canteen in case you distracted the men on their lunch break. And what’s worse, you’d be told by all and sundry that you were unnatural – an oddity. You would be treated as an outcast. Men don’t want to marry ‘academic’ women, they want quiet wives who will be obedient spouses and good mothers. Who wants a wife with aspirations?! God forbid!

In the 1800s, most people (women included) fervently believed that a woman’s place was in the home. To be a nice, demure wife, who provided dinner and raised children, was the standard. Woe betide the woman who dared to have an opinion, let alone wanted a job! The idea that women might attempt to be more like men by pursuing careers was seen as the beginning of the end of society.

There was an overwhelming belief that women should not enter higher education. Many women didn’t go to secondary school, and those that did learned only the feminine arts, like needlework and flower arranging. Women didn’t need to learn; they just needed to behave. Therefore, most universities kept their doors firmly closed to women, regardless of how brilliant their minds were.

Reading about this – a subject on which I knew nothing – shocked me profoundly. I might have believed it, had it been hundreds of years ago, but this wasn’t the experience of women in ancient societies. It was little more than a century ago. My grandmother was born in the following decade. And this was happening in England. It felt very close to home.

I count my own university years as some of my happiest and most rewarding. It was a time when I was allowed the opportunity to grow up, flex my mental muscles and discover who I might go on to be. The idea that society would be appalled by women like me and my friends, who simply wanted to study, seemed outrageous. At first it made me angry; then it made me think; then, crucially, it made me want to speak. To talk about this injustice. To tell everyone that it happened. That here, in Britain, there was a time when women weren’t allowed to think and learn, and had to fight for their right to an education. To remind us how lucky we are to have access to learning, when so many women in the world don’t. In developing countries, as I write, one in two girls don’t have access to secondary education. Many have no access to education at any level. Today. The greatest way to empower people is to give them knowledge – to educate people so they can help themselves. Education is important and it is a right. It’s there in the Geneva Convention, alongside the right to freedom and the right to life. I wanted to write about that.

So there I was. With a subject I felt passionate about that needed a platform. And how could I make that happen? Simple. I worked in the theatre; it had to be a play.

The idea of making the play, however, was daunting. Creating a play is a huge task, and whilst I had directed many, I’d never written one. I needed to find a writer, who could write the script, which I would direct. But then I began imagining. I started to imagine a girl getting off the train, her dainty shoes a stark contrast to the crowd of men’s feet on the platform. I started imagining the girl who has to retake the year because her nerves get the better of her. The boy who meets the girl... the brave teachers and their sacrifices... the funny lessons on bikes...

And that was it. I couldn’t possibly hand it over to someone else. I had gone too far. I had to write it. And that was the beginning of Blue Stockings.

And when I wasn’t sure where to start, I returned to the research. I looked at pictures. I delved into the archives at Girton College. Wading through their stacks, I came across portraits, photographs of lectures and images of old Cambridge. But there was one single picture I couldn’t take my eyes off – an image that became the touchstone of the play and gave me motivation to write every time I lost my nerve.

It was a small photograph, taken in 1897, blurred and in black and white. In it, a mannequin is hoisted high on ropes above a street packed with men in boater hats. The mannequin is a girl on a bike, wearing blue stockings (a symbol of academic women). She’s strung up, helpless, a grim mockery of university women. Underneath her, the crowd are protesting. Nearby, students are throwing rocks and pulling down theatre hoardings. And, shortly after the picture was taken, the mannequin was paraded through the streets and set on fire, like Guy Fawkes, whilst onlookers whooped and cheered as the effigy of a young woman was burned in the heart of the city. And why? Because women had had the audacity to ask for the right to graduate. Asked to be recognised for work they had done. Having studied for three years, on identical courses to the men, all they wanted was for their qualifications to be recognised. And they were denied.

The emotions present in that moment. The fear that makes people burn effigies. The certainty with which the university campaigned to keep women out. The fact that men returned in their hundreds to vote against the women. And yet, in the face of this hatred and injustice, those girls sacrificed everything to stay. And they couldn’t have done it without brave teachers, often men, who put their own careers on the line to stand by their female students.

This was a time of turbulence and social change on a far wider scale. Industrialisation had swept the nation and changed the face of our towns and cities. We were on the verge of the Boer War, and the suffrage movement was beginning to spread. Change induces fear, and for many, women’s will to challenge the status quo was the tip of a much more dangerous iceberg in which England, as they knew it, was on the brink of irreversible change. If women weren’t content to stay at home as housewives, what would happen to the country? Who would nurture the children? What would become of the family? The nation? It would be a disaster.

Blue Stockings is a fictional story, inspired by real events. It tells the story of a group of extraordinary girls in their first year at Cambridge. The year is 1896. The girls were expected to develop into polite young ladies, with harmless hobbies like embroidery and flower arranging, before settling down to married lives. But was that enough for them? Absolutely not.

They were women who wanted more. Who wanted experiences outside the world they were born in to. Women who I wanted to write about and who deserve to be remembered. Women who wanted to know. To understand the properties of light. To translate Virgil. To cure diseases, to invent, to comprehend the boundaries of space. They wanted to learn. And they would do anything for the chance to do so.

Blue Stockings is the story of those girls.

I wanted to call it Blue Stockings because the term tells us something of the perception of educated women over time. ‘Bluestocking’ was originally coined in the 1700s to describe clever women who met at literary salons to discuss intellectual ideas. Thus, to be a member of a Blue Stockings society was desirable and a privilege; to have knowledge and to be a little learned was seen as a classy pursuit. But, over time, it became a derogatory phrase used to poke fun at women who were perceived to be scholarly oddities – women who didn’t match the feminine ideal. So I wanted to reclaim the term.

Blue Stockings is two words as it is a deliberate reference to the clothing: in the play, the boys buy blue stockings to put on the effigy. Stockings are also a symbol of sex and female sexuality. It’s a bit cheeky. As the then Artistic Director of Shakespeare’s Globe, Dominic Dromgoole, said to me, ‘Good title, Blue Stockings. The women’ll come cos they’ll think it’s feminist; the men’ll come cos they’ll think it’s sexy.’

Some of you reading this book will likely be staging your own productions of Blue Stockings. I hope you enjoy this text as a helpful and inspiring resource. Compiled with my assistant director Lois Jeary, a formidable mind and a first-class researcher, this guide aims to take you through the process of staging the play, to consider each of the elements of production, from sound and music to design and rehearsals. You’ll also find notes from our rehearsal process, extracts from my working diaries, notes and exercises, ideas for you to try, and contextual research to immerse you and your company in the world of the play.

‘Let the petticoats descend!’

Jessica Swale

The playtext of Blue Stockings by Jessica Swale is published by Nick Hern Books (revised edition, 2014, ISBN 978 1 84842 329 9), and can be purchased with a discount from www.nickhernbooks.co.uk. All page references in this book are to this edition.

Cambridge on the day of the vote, 1897. Courtesy of the Mistress and Fellows, Girton College, Cambridge.

Blue Stockings In Rehearsal

The World of the Play

Blue Stockings is set in 1896–7 – a time when Queen Victoria was on the throne, the colonies of the British Empire spread from Newfoundland in the northern hemisphere to New Zealand in the southern, and only men who owned or rented property above a certain value had the right to vote.

In terms of both the law and the way society viewed them, Victorian women were second-class citizens; so the women in this play have a great deal to fight against, if their aim is to be taken seriously as intelligent citizens who might like the chance to work.

Understanding the historical context is crucial to telling the story of the play. Although the play is firmly set in Victorian England, there is a contrast between the expectations this sets up and the way its female characters behave. They are not your typical Victorians, and therein lies the drama. They are women who defy the conventions of their time; Jessica says the characters are ‘bursting out of their corsets – trying to move forward before their peers have caught up. It is important that, whilst they inhabit a Victorian world, the women’s energies and sensibilities are ahead of their time. That’s where the interesting juxtaposition lies.’

The actor, director or designer’s primary task is to interpret and bring to life the characters and text. Blue Stockings features both real and fictional characters and incidents, so thoughtfully applied research can illuminate those interpretations. Everyone uses research in different ways and, although some might do it purely for their own information, establishing ways to share findings amongst a cast ensures that everyone works from the same starting point.

In rehearsals, Jessica often gives each cast member a particular topic to research and then asks them to present their findings to the rest of the company, so that all can share in building the world of the play. It is important that actors choose a topic that relates to their character so that the research is useful rather than simply academic. Jessica also encourages actors to find a playful, fun, inventive way of sharing their findings, rather than simply giving a talk full of dry information. They may present it in an exercise, as a playlet or as a chat show. When rehearsing Hannah Cowley’s eighteenth-century comedy of manners The Belle’s Stratagem, they even had one research session that spoofed an episode of Made in Chelsea! The more palatable and active the information becomes, the more it will go in.

Here is a list of suggested research topics, followed by an introduction to some key themes:

• The history of Girton College – including Elizabeth Welsh and her predecessor, Emily Davies.

• The daily routine at Girton.

• The riot and the vote on women’s graduation rights.

• The role of a university lecturer at Cambridge.

• What courses consisted of at Cambridge.

• What social lives were like in Cambridge.

• The geography of Cambridge – the town, the locations in the play, and what there was to do.

• Social class at Cambridge and beyond.

• Famous Cambridge students and their experiences.

• The science of the play, and astronomy in particular.

• Hysteria – the study of it and what people believed about it.

• Relationships – marriage, courting and expectations.

• Suffrage.

• Politics of the 1890s.

• Arts of the 1890s.

THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND

‘Under exclusively man-made laws women have been reduced to the most abject condition of legal slavery in which it is possible for human beings to be held.’1

Florence Fenwick Miller, in a speech at the National Liberal Club, 1890

The women in Blue Stockings defy society’s expectations of them. In order to communicate this spirit and zeal, actors need to have an understanding of what those historical constraints were. It is also helpful to appreciate that the play is set in a time when the position of women in society was starting to shift and campaigns for women’s rights were gathering momentum.

The nineteenth century was a time of division between the sexes that crystallised in the doctrine of men and women occupying separate spheres. The man’s role was considered to be engaging in public and economic life – going out to work, being the wage earner and representing the family in matters of law or politics. Meanwhile, the woman’s place was in the home with all its attendant domestic responsibilities, such as cooking, needlework and, perhaps most importantly, raising children. As the morally superior and yet physically weaker sex, middle-class Victorian women were to be shielded from the corrupting influence of society at large.

This was demonstrated through the rights that women were afforded. Before the 1880s, when a woman married, her property passed to her husband’s ownership and her individual legal identity ceased because she and her husband were considered to be one person under the law. In 1857, an Act of Parliament had made it easier for married couples to obtain a divorce; however, it ensured that doing so was much easier for men than women. For a man to obtain a divorce he needed only to prove that his wife had been unfaithful; for a woman to get a divorce she had to prove her husband’s infidelity and cruelty. Historically, the custody of children also passed to men. That had gradually started to change from 1839 onwards, when women started to acquire rights of access and custody for children in certain cases; however, a husband essentially retained rights over his wife’s body and the products of that ownership, which included children.

Many of those gradual gains in the legal status of women resulted from organised movements and campaigns. Arguably the biggest movement of the latter half of the nineteenth century was the campaign to grant women the right to vote. At the start of the century only a small percentage of wealthy men were entitled to vote; as the years went on, however, a series of reforms extended that right to more and more men. In 1866, a petition was presented to Parliament calling for women to have the same political rights as men, but the measure was defeated. Groups supporting women’s suffrage emerged across the country and in 1897 a number of them joined together to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, led by Millicent Fawcett.

The campaign for women’s suffrage can be broadly categorised into the ‘suffragists’, who campaigned through non-confrontational means, such as petitions and public meetings, and the ‘suffragettes’, who believed that radical methods were needed to achieve results. The Women’s Social and Political Union, founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, was a militant organisation that advocated for disturbances, such as window-breaking and arson, to command the attention of the press, politicians and public.2 As a result of their actions, hundreds of women were imprisoned, and the many who went on hunger strike endured force-feeding by the prison authorities. In 1918 the vote was granted to women over the age of thirty who met certain property qualifications. Then in 1928 the franchise was extended to all women over the age of twenty-one, granting women the vote on the same terms as men.

One of the highest profile opponents of the suffragists’ cause was Queen Victoria, and the significance of her reign to attitudes regarding women’s rights must not be underestimated. She was perceived as the epitome of womanly virtue during her reign from 1837 to 1901. Despite her being the most powerful woman in the world, various comments attributed to Queen Victoria suggest that she thought women should stick to their domestic sphere. Victoria was devoted to her husband, Albert, and they had nine children together; however, when Albert died at the age of forty-two, she went into deep mourning and resisted public engagements. At that time, the Queen’s withdrawal from public life attracted criticism and added weight to arguments that women were too volatile for public office.

The nineteenth century was even harder for women at the other end of the socio-economic spectrum. Working-class women had no choice but to work, often in domestic service or factories, to support their families, yet hours were long and wages were low. Housing conditions for the poor were crowded, although the only alternative for people who could not support themselves was to go into a workhouse. Gradually, however, working women organised into groups. In 1888, women and girls working at the Bryant and May match factory in London went on strike over unfair dismissal and their working conditions; eventually their demands were met and their strike led to the formation of the Union of Women Match Makers. Occasionally women from more privileged backgrounds had to work, usually as governesses, teachers or nurses, and some of those women were to form the vanguard for women’s education.

In the first half of the century, the education of women in England was entirely piecemeal. A lucky girl may have been allowed to join her brother’s lessons with his tutor, or attend the local church school, while others may have benefited from the instruction provided by governesses, but generally girls were schooled in only those ‘accomplishments’ needed for a blissful domestic life: music, drawing, dancing and needlework. Gradually, secondary schools were established to provide a more rounded education to girls, and by the end of the century universities and colleges were enabling women to study at a level never previously available to them.

GIRTON COLLEGE AND THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

‘A flowing river is no doubt more troublesome to manage than a tranquil pool; but pools, if let alone too long, are apt to become noxious, as well as useless.’3

Emily Davies, founder of Girton College, The Higher Education of Women, 1866

In 1869, Emily Davies co-founded the first English college to offer a degree-level education to women: Girton College.4 Initially, the college’s five female students lived in Hitchin, a town thirty miles south of Cambridge, taking classes from Cambridge lecturers who were supportive of their cause, but in 1873 the college and its fifteen students relocated to the outskirts of Cambridge. The building was designed by Alfred Waterhouse in a neo-Tudor style constructed out of red brick, and even the architecture seemed determined to challenge the status quo: in contrast to a lot of the older colleges, the rooms at Girton were arranged along corridors rather than around staircases.5

In the meantime, Newnham College had been set up as a home for women to live in while they attended lectures at Cambridge, yet the approaches and profiles of the two institutions differed markedly. Whereas Newnham allowed women to study at the level and pace that suited them, Girton aimed for its students to match the men from the outset. Emily Davies believed that the curriculum offered to women should reflect what was being offered to men, so the students at Girton took preliminary examinations before starting out on their chosen Tripos (honours degree).6 They did so despite having no official recognition from the university, which took until 1881 to allow the women to sit its examinations formally (and until 1948 to award them degrees).

Almost from the outset, the University of Cambridge lagged behind other institutions in terms of women’s education. In 1878, London University became the first to award women degrees, and affiliated colleges around the country offered women opportunities denied to them at the country’s leading academic institutions. What accounts for Cambridge’s reluctance to allow female students to study and graduate on equal terms to men? The university’s tremendous history and the weight of tradition must certainly have played their parts.

The University of Cambridge was founded in 1209 and is made up of constituent colleges, the eldest of which is Peterhouse. Trinity College (where all the male characters in Blue Stockings, except Will, study or teach) was founded by Henry VIII in 1546, more than three hundred years before Girton was established. Cambridge therefore represents centuries of tradition and of educating the country’s male leaders, scientists and poets. Until 1926 the highest governing body in the university was the Senate, which was comprised of all graduates.

From speaking to the King’s College archivist, Jessica discovered that it was not until the 1880s that King’s began to admit boys through merit. Before that it was entirely through privilege; if you went to Harrow or Eton, you did not have to sit the exam to get in, you just got given a place. In 1896, eighty per cent of the Fellows (the role that Mr Banks is offered at Trinity) would have been Etonians, and boys often brought their servants with them to college. She also discovered that King’s College voted to allow lecturers to decide individually whether to allow women into their lectures or not, rather than imposing a blanket policy upon them.

When the question of admitting women to the university was first raised, it was perceived as a threat to tradition. Then, as now, Cambridge provided students with a rigorous, highly academic education and was one of the most respected higher-education establishments in the world. Admitting women, who would most likely not have had the same level of schooling as their male counterparts, posed a risk to that reputation. Moreover, the university was so ingrained in the livelihoods of the British Establishment that, for some, the fact that the women’s colleges admitted students from a more diverse range of socio-economic backgrounds threatened the privilege they enjoyed – and the British class structure as a whole.

For the women who got to Girton, it nonetheless provided opportunities to study and socialise in ways that had been hitherto unimaginable. Along with those freedoms, there came responsibilities, and students found their days and nights regimented and regulated by college authorities, who were cautious not to allow any scandal to derail their mission.7 It was also not unusual for a student’s education to be interrupted by pressures from home. For example, Constance Jones, who later succeeded Elizabeth Welsh as Mistress of Girton, was in her mid-to-late twenties when she matriculated in 1875. Jones was the eldest of ten children and the education of her brothers was of higher priority; various interruptions to her studies meant it took her five years to achieve a first-class pass in her exams.8

Trips to Girton informed much of the early work on the play. When Jessica and designer Philip Engleheart visited Cambridge they subjected themselves to the ‘Girton grind’, walking uphill from the centre of town to Girton. When they finally reached the college, an unexpected entrance revealed how students might have snuck past the disciplinarians. ‘There was a little short cut through some bushes, which I think is the way we got to it,’ Philip says. ‘Imagining that it was the exact way the lads would have got in, or the girls would have got out, was really exciting.’

Visiting Cambridge certainly helped actress Verity Kirk to understand what Girton would have meant to her character. ‘Everyone always says that it is magical – and it is,’ she says. ‘Going into rooms where there are just books and books and books, you get the feeling of what that would have meant to somebody who loves to read.’ To her, Cambridge ‘felt like it had this legacy of learning that sucked you in and felt like the only place in the world.’

Jessica’s Reflections on the Research Trip

In every production I’ve directed, I’ve tried, if possible, to do a relevant day trip. Not only can it offer great research opportunities towards understanding the world of the play, but it’s a great opportunity to bring the company together and to help them all invest in the piece as a group. We visited a sheep farm for an adaptation of Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd, and Austen’s house for Sense and Sensibility, went to Bath for Sheridan’s The Rivals and to an Iraqi centre for Judith Thompson’s Palace of the End. So, of course, nothing would make more sense than for the cast and crew of Blue Stockings to spend the day in Cambridge.

We organised visits to the archive at both Girton and King’s (an all-male college until the twentieth century), and also visited places featured in the play. But, I think, more than the specific fact-finding, to spend time in the city helps them to understand the scale of the fight. The college buildings are so grand and imposing, it’s rather like standing amidst cathedrals. The air of formality, the scale of the architecture, the gown-wearing, the manicured lawns – it really hasn’t changed much since the time the play is set. It was fascinating, and pretty incredible, to think the action of the play, to a large extent, really happened. To look at the window where they hung the mannequin. To work out which shop would have been the haberdashery where the confrontation takes place... There’s a wooden-beamed, old-fronted shop right on the market square; I think it’s there – I can almost see Holmes going in now to buy his gloves from Mrs Lindley. All in all, a very moving experience.

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

‘The advantage of the emotions is that they lead us astray, and the advantage of science is that it is not emotional.’

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1891

The nineteenth century was a time of startling technological advancement following the Industrial Revolution of the previous century. The characters in the play would have directly benefited from developments, like the growth of the railway and steam travel; and would have been aware of major scientific discoveries, like the pasteurisation process. Yet recognising how recently life-changing technologies like the light bulb were invented also helps actors to appreciate how forward-thinking the characters are, and how the women’s studies place them at the cutting edge of scientific endeavour.

The following is a timeline of the major scientific and technological advances in the years immediately preceding the time in which the play is set. It is based on a list of inventions that Jessica compiled during her preparation and shared with the actors:

1824 First public steam locomotive carries passengers.

1838 First photograph is taken using the daguerreotype process.

1839 Pedal bicycle invented by a Scottish blacksmith.

1840 Postage stamps are used in England for the first time.

1843 The first Christmas card is sent.

1844 The first Morse code message is sent.

1845 First inflatable rubber tyre designed.

1846 Discovery of the planet Neptune.

1850 The domestic Singer sewing machine is invented.

1852 First public flushing toilets open in London.

1853 Postboxes first used in Britain.

1859 Charles Darwin publishes On the Origin of Species.

1863 The first London Underground line opens for business.

1872 The penny-farthing bicycle is invented.

1873 The first typewriter with a QWERTY keyboard is manufactured.

1875 Cadbury makes its first chocolate Easter egg.

1876 Alexander Graham Bell is granted a patent for the telephone.

1878 Electric street lighting is first introduced in London.

1879 Albert Einstein is born.

The light bulb is patented.

1883 Britain’s first electric railway line is built in Brighton.

1885 First motor car built.

1886 Sigmund Freud sets up his clinical practice in Vienna.

1887 The Gramophone is invented.

1888 The Kodak camera and film is made available to consumers.

1894 Moving pictures (‘the movies’) first comes to Europe from America.

1895 First radio signal sent.

The X-ray is discovered (as Edwards talks about in the play!).

Character Profiles

THE GIRTON WOMEN

TESS MOFFAT is a first-year student at Girton College in Cambridge. She is one of a small yet significant number of women who are studying at university level in the country at this time, and although the students at Girton take classes and examinations, they do not yet have the right to graduate. At Girton, Tess has a passion for astronomy and ambitions to travel across South America charting the stars. Her essay on Kepler is used as an exemplar by both Mr Banks and Mrs Welsh to demonstrate the academic capabilities of a woman’s mind.

As a young girl, Tess was always hungry for knowledge. In Act Two, Scene Nine, she recalls climbing on to the roof of a local school so that she could eavesdrop on the lessons, which tells us that whatever minimal education she had access to was not enough for her. She admits she used to ‘wreck Mother’s nerves with worry’ and if Tess was not initially allowed to attend school, perhaps that incident might have encouraged her parents to let her do so.9

We learn more about Tess’s home life in Act One, Scene Eight, when she is visited by her childhood friend, Will Bennett, a student at King’s College. Will has promised Tess’s father that he will look out for her while she is at Cambridge, but tells her: ‘Your father had no idea what he was sending you in to’ (p. 43). Although Tess’s parents are supportive of her studying at Cambridge, and have given her permission to do so, Will suggests that they would be uncomfortable with the recent events at Girton, as the college gears up to campaign for the women’s right to graduate.

Although Girton might have appeared to be a place where women could go and study quietly, the graduation campaign will put it in the spotlight, perhaps nationally. Tess’s parents would probably want to protect her reputation by making sure she is not associated with any political activity, particularly if the campaign has any association with suffrage. We might expect that Tess’s parents would have sought to shelter her from such controversy when she was growing up.

Tess is unmarried and does not have children, although in Act Two, Scene Five, she tells Celia that she would like to be a wife and mother one day. In Act One, Scene One, Tess first tells Carolyn about Will. Later, Will declares his love for Tess, but she is unable to reciprocate as she has fallen for another student, Ralph. When Ralph meets another woman and decides to propose, it falls to Will to tell Tess. The play ends with Will promising to wait for Tess until she feels able to love him, but it is interesting to consider how and when Tess realises that Will could be the man for her.

Tess is the first student that the audience meets, and she is the central protagonist. The character evolved considerably during the writing of the play. In the early version of the script performed at RADA, the central protagonist was called Gertie Moffat; by the time the play was produced at Shakespeare’s Globe, her name had been changed to Tess and the key events of the play were reshaped around her. In early drafts, the incidents of the play were more equally divided between the four female students; however, when redrafting for the Globe, Jessica ensured that the story was told more from Tess’s perspective: ‘I wanted the play to be more filmic, and films are almost always focused through one character’s perspective. There’s so much story to tell in Blue Stockings, I thought we would invest more fully if we were allowed to see the whole of one character’s experience, rather than splitting our time. That’s why I refashioned the play around Tess. And I changed her name because I thought “Gertie from Girton” just sounded silly!’

Jessica’s Reflections on Writing for a Central Protagonist