14,95 €

Mehr erfahren.

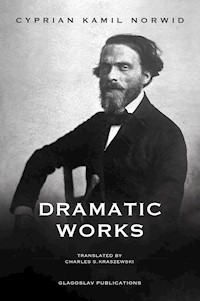

- Herausgeber: Glagoslav Publications B.V. (N)

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

‘Perhaps some day I’ll disappear forever,’ muses the master-builder Psymmachus in Cyprian Kamil Norwid’s Cleopatra and Caesar, ‘Becoming one with my work…’ Today, exactly two hundred years from the poet’s birth, it is difficult not to hear Norwid speaking through the lips of his character.

The greatest poet of the second phase of Polish Romanticism, Norwid, like Gerard Manley Hopkins in England, created a new poetic idiom so ahead of his time, that he virtually ‘disappeared’ from the artistic consciousness of his homeland until his triumphant rediscovery in the twentieth century.

Chiefly lauded for his lyric poetry, Norwid also created a corpus of dramatic works astonishing in their breadth, from the Shakespearean Cleopatra and Caesar cited above, through the mystical dramas Wanda and Krakus, the Unknown Prince, both of which foretell the monumental style of Stanisław Wyspiański, whom Norwid influenced, and drawing-room comedies such as Pure Love at the Sea Baths and The Ring of the Grande Dame which combine great satirical humour with a philosophical depth that can only be compared to the later plays of T.S. Eliot.

All of these works, and more, are collected in Charles S. Kraszewski’s English translation of Norwid’s Dramatic Works, which along with the major plays also includes selections from Norwid’s short, lyrical dramatic sketches — something along the order of Pushkin’s Little Tragedies.

Cyprian Kamil Norwid’s Dramatic Works will be a valuable addition to the library of anyone who loves Polish Literature, Romanticism, or theatre in general.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 615

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Dramatic Works

Cyprian Kamil Norwid

Translated byCharles S. Kraszewski

Glagoslav Publications

Dramatic Works

by Cyprian Kamil Norwid

Translated from the Polish and introduced by Charles S. Kraszewski

This book has been published with the support of the ©POLAND Translation Program

Publishers Maxim Hodak & Max Mendor

Introduction © 2021, Charles S. Kraszewski

© 2021, Glagoslav Publications

Proofreading by Stephen Dalziel

Book cover and layout by Max Mendor

Cover image: Photo of Cyprian Norwid by Michał Szweycer, 1856

www.glagoslav.com

ISBN: 978-1-914337-33-8 (Ebook)

Published in English by Glagoslav Publications in December 2021

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is in copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Contents

INFURIATING AND SUBLIME

Charles S. Kraszewski

A MOMENT OF THOUGHT

SWEETNESS

AUTO-DA-FE

CRITICISM

THE 1002ND NIGHT

ZWOLON

WANDA

KRAKUS, THE UNKNOWN PRINCE

IN THE WINGS

PURE LOVE AT THE SEA BATHS

THE RING OF THE GRANDE DAME

CLEOPATRA AND CAESAR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE TRANSLATOR

Notes

Dear Reader

Glagoslav Publications Catalogue

INFURIATING AND SUBLIME

INFURIATING AND SUBLIME

Charles S. Kraszewski

Several weeks ago, when I was nearing the end of this translation, I met a friend of mine for coffee. As he too is a poet and translator, and above all, a Pole, he smiled knowingly when I mentioned that I was working on Cyprian Kamil Norwid’s dramatic texts in preparation for the bicentennial of the poet’s birth.

‘What do you think of him?’ he asked.

‘I find him by turns infuriating and sublime,’ I said, although, admittedly, I used some rather less diplomatic language in place of that first term, which I choose not to repeat here.

‘Exactly,’ he replied, with a laugh.

And this is the general reaction of Poles when confronted with Cyprian Kamil Norwid, the great, quirky, lonely individual talent of the second generation of Polish Romantics. He is a genius — there are moments… check that… actually hours or days of magnificence and brilliance in his work; there are also moments… or, to continue with the metaphor of time, let’s say uncomfortable minutes, when his sublime genius outsoars our ability to follow. Norwid has a tendency to twist the Polish language into a form that, while it may — to him — more closely approximate exactly to what he wants to say, can be so strange that — to us — it becomes incomprehensible or (what is worse),

cute.

The English reader thus has a firm walking staff with which to steady his tread as he sets out to cross the elevated, yet uneven terrain, of Norwid’s poetic highlands — he already knows someone quite like him.

cyprian kamil norwid: poland’s gerard manley hopkins

When Robert Bridges brought out the collected poems of his deceased friend Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844 – 1889) in 1918, he did so, courageously, with a true poet’s intuition for great writing. He also did it with trepidation. Bridges was the poet laureate — a position not attained by going against tradition — which is exactly what Hopkins did. Although he was blamed by some of the younger generations of early twentieth century poets for ‘suppressing’ Hopkins’ work for so long, one cannot fault Bridges for his sensitivity to the capabilities of the wider public to digest the exotic fare prepared by the Jesuit poetic genius. One has grown accustomed to smirking at Bridges’ apologetic warning to the reader concerning ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland,’ traditionally printed at the very beginning of Hopkins’ works, as a ‘dragon folded at the gate to forbid all entrance,’1 but that is patently unfair. To switch to a culinary metaphor, Bridges is following soberly in the footsteps of St Paul, who in his letter to the Hebrews warned his auditors that they ‘are become such as have need of milk, and not of strong meat.’2

Again, our reference to Hopkins is not random. In nineteenth century Poland — or, rather, in the nineteenth century Polish diaspora — Cyprian Kamil Norwid (1821 – 1883) traversed an artistic arc quite similar to that of his British near-contemporary. A serious Catholic, Christianity so forms the basis of Norwid’s writings that, as Jan Ryszard Błachnio notes, he ‘significantly influenced … both methodologically and conceptually,’ the formation of John Paul II’s personalistic philosophy.3 As an artist, he was ahead of his time, departing from tradition, coining words as well as using words well-known in startling new contexts, just as Hopkins did in England.

In order to describe the world more precisely, the poet coined new words, or extracted latent meanings from words that already exist, breaking them down into constituent portions or ‘coping’ words that were previously separate. As some scholars see it, Norwid was to the Polish language what Dante was to the Italian: ‘a translator of a theological language’ before professional theologians even set themselves to the task.4

The statement comparing Norwid to Dante may be true enough as far as their ‘theological’ content is concerned, but it would be an overstatement to carry the comparison into the literary field. For Dante, known and appreciated in his own time, whether loved or hated by his contemporaries, is also the chief creator of the modern Italian literary idiom itself. Norwid, on the other hand, like Hopkins in England, is indeed of seminal importance to the development of the contemporary poetics of his native speech, but only belatedly. Just as Hopkins had to wait, so to speak, nearly two decades after his decease to join the literary conversation in England and the English-speaking world, so Norwid, though befriending earlier poets of the Romantic generation such as Zygmunt Krasiński and Juliusz Słowacki and corresponding with Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, was generally unknown to the wider public in Poland until the chance discovery in 1897 (and thus, fourteen years after his death), of his work in a Vienna library by Zenon Przesmycki, who first went on to champion it. Ever since his adoption by the poets of the ‘Young Poland’ movement at the turn of the twentieth century, Norwid’s star has been in the ascendant. He is the darling of all aficionados of ‘challenging’ poetry; those who are fond of T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, or the afore-mentioned Gerard Manley Hopkins, will probably be attracted to Norwid’s work; fans of the (forgive me) undemanding sort of poet like William Wordsworth or Robert Frost, or the Beats like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, will most likely find him a bit too arcane.

The above is not at all intended as a dismissive statement. There is much to be said in favour of clarity and simplicity in poetic expression; Pound himself once stated that ‘poetry must be as well written as prose,’5 and for those who see the Apollonian, or classical, approach to poetry as something of an eternal standard, Norwid’s approach could only be taken as a fad, or an aberration. This reputation has dogged Norwid since his earliest years. The neoclassical poet Kajetan Koźmian, who hosted Norwid in 1842 during the latter’s trip through Kraków, noted this summation of the younger poet’s talents in his Memoirs (posthumously published in 1865):

Carried on the winds of popular opinion [Albert Szeliga Potocki] raved about Norwid, a good and pleasant young man, whom I met personally, in my own home, where I hosted him for several days. But although he drew very prettily, he wrote in too incomprehensible a way. Warsaw was echoing at the time with cries such as ‘Norwid, you eagle, your age is approaching!’ Potocki sent me his poems, completely incomprehensible, along with effusions of praise. When I charged him with levity in his judgement [płochość w sądzie] he began to squirm like a snake, admitting the justice of my charge to my eyes, while behind those eyes saying something else.6

The sort of thing that Koźmian finds ‘incomprehensible’ and many readers today find irritating, at least, is Norwid’s penchant for creatively deforming the Polish language by the creation of new words, such as we find in his lyric poetry, like wszechdoskonałość [‘universalperfection’] niedośpiewana [‘unsungtotheend’] and ożałobione [‘mourningshadowed’] all of which occur in one of his most famous poems, ‘Fortepian Szopena’ [Chopin’s Grand Piano], being a lament for both Chopin’s death, and the martyrdom of Warsaw at the hands of the Russians. Norwid gives free rein to his imagination in lyric poems — something that might be expected, taking into consideration the intimate nature of the genre, which, given the way communication occurs between poet and reader, may well embolden creative minds to striking linguistic experimentation shunned in other forms of literary composition. Readers of English poetry might be reminded here of E.E. Cummings at his best (or worst, depending on your point of view).7 In his dramatic works, Norwid coins words too. For one example, in Zwolon’s poetic monologue in the play of the same name — modelled on the Great Improvisation from Mickiewicz’s Dziady [Forefathers’ Eve], Part III (and thus a lyrical monologue) the character employs the metaphor of multi-faceted life as a lyre, or chord, a metaphor which was a favourite of Norwid’s. And here, the poet indulges in creative license with the phrase pierwsza odśpiewa / całostrunna (which we render as ‘the former sings / striking all-strings’).

The reader familiar with the Polish originals of these plays might well offer some other examples; the old-Slavic sounding title bestowed upon Prince Rakuz (in Krakus), Włady-Tur, a calque of ancient Slavonic roots signifying authority and the virile strength of a bull, is one that leaps to mind. However, in general, with a dramatist’s intuition, Norwid eschews such verbal gymnastics in his plays. Drama is not only a collaborative genre, obviously, it also relies on the immediacy of verbal communication, and the natural tempo of stage action allows for precious little pausing on the receptors’ part to puzzle out strange — if effective and rich — unfamiliar terms. As can be seen from his various introductions and initial didascalia to the plays, Norwid was concerned with their proper performance, whether he foresaw them as being staged, or read aloud by amateurs at social gatherings. In the introduction to Cleopatra and Caesar, he even goes so far as to warn the performers to pay special attention to the exigencies of metre, as in this poetic drama in blank verse they are deprived of the crutch of rhyme. Consequently, except where such was absolutely necessary — as in the case of the above-mentioned soliloquy from Zwolon, so strikingly similar, stylistically, to ‘Fortepian Szopena’ — I have generally smoothed over Norwid’s coinages where they appear, for to retain them would run the risk of creating a preciosity not entirely present in the Polish originals.

As a matter of fact, Norwid himself realised the danger of too violent a racking of everyday speech. In The Ring of the Grande Dame, the rather unpalatable character of Judge Durejko is satirised by his grotesque devotion to ‘purifying’ the Polish language by replacing foreign loan-words, such as ‘monologue,’ with Slavic coinages like sobo-słowienie [‘selfspeaking’] — derived from the works of the ‘national philosopher’ Bronisław Trentkowski. Just as the fashion for re-Slavicising Polish ended almost as soon as it began (and Norwid knew this, and laughed at it), and Trentkowski is a rather forgotten figure today, so Norwid cannot be said to have had the same sort of linguistic impact on Poland as Dante had on Italy. What characterises much of his poetic idiom — such quirky word-builds as described above — was not accepted into common parlance, except for a brief, though marked, influence on poets of the Young Poland period. And this influence was indeed brief; it did not extend much past the słopienie [‘wordcrooning’] of Julian Tuwim, and generally grates on the Polish ear today.

Despite all the boldness we usually associate with Cyprian Norwid, as a poet and a man, his great characteristic is modesty. He did not consider himself to be a lawgiver. In the strange unfinished drama Za kulisami [In the Wings], the play within this play, Tyrtaeus, written by the main character Count Omegitt, is whistled off the stage. Glückschnell, the theatrical promotor who (for reasons unclear) accepted the drama for production, explains its failure as partially arising from the author’s long absence from commerce with the living language of his nation:

In complete confidence, I would not conceal this from an interested party like yourself: by nature of his long and far-distant travels, he’s lost the active native pulse that, on the one hand, lends a writer’s language its peculiar strength, and on the other, incessantly fortifies his thought with the current needs of our society — and that is, I would say, what pleases… everyone.

If Norwid’s poetic language — in these dramas or in his verse and prose — is taken into consideration, I feel that we would be hard put to consider it as a good example of the Polish current in his day. His older friend Zygmunt Krasiński, who most people would agree does not rise to the same level of poetic quality as Norwid, still has a rather limpid style in the prose he employs in his dramas. For example, consider this fragment from Krasiński’s Nieboska komedia [Undivine Comedy] — an intricate condemnation of the Count’s forefathers by the revolutionary Pankracy, as the two debate in the portrait-hung walls of the former’s palace:

Oh, sure — praise to thy fathers and grandfathers on earth as in… Yes, there’s quite a lot to look at around here.

That one there, the Subprefect, liked to shoot at women among the trees, and burned Jews alive. — That one, with the seal in his hand and the signature, the ‘Chancellor,’ falsified records, burned whole archives, bribed judges, hurried on his petty inheritances with poison. — To him you owe your villages, your income, your power. That one, the darkish one with the fiery eye, slept with his friends’ wives — that one with the Golden Fleece, in the Italian armour, fought — not for Fatherland, but for foreign pay. And that pale lady with the black locks muddied her pedigree with her squire — while that one reads a lover’s letter and smiles because the sun is setting… That one over there, with the doggie on her farthingale, was whore to kings. — There’s your genealogies for you, endless, stainless! — I like that chap in the green caftan. He drank and hunted with his brother aristocrats, and set out the peasants to chase deer with the dogs. The idiocy and adversity of the whole country — there’s your reason, there’s your power. — But the day of judgement is near at hand and on that day, I promise you, I won’t forget a single one of you, a single one of your fathers, a single scrap of your glory!

Compare this to a direct address of similar length from the Tyrtaeus section of In the Wings. Laon, returning home, addresses his stepfather Cleocarpus:

To see you at rest, O my lord and my father, I don’t know how fast I’d be able to urge my legs, but I was told at the Pnyx (something I might have surmised myself) that the debates at the Aeropagus on this pregnant night were to last long (as if they were ever any less weighty, any different). And so, in order not to be too far distant from your thoughts and wishes, I gladly accepted the call of my superiors to see to the men working at the port, to whom a free hand is proper, to the craftsmen who busy themselves with things which, if I may say so, are not completely unfamiliar to me. And there, like a fresh nut which, perfect in its roundness, sloughs off its heavy green coat when it is golden and ripe, thus did we slide into the waters of the sea a skilfully constructed, new Corinthian galley — not without the usual libations and the first gay turn around the harbour.

The first of these, that of Krasiński, reads smoothly, even in English translation, if I may be so bold to suggest; it is easy for us to suspend our disbelief and ‘be there’ in the chamber listening to the fierce exchange, following the ideas, not burdened at all by strained syntax. But Norwid’s fragment? Did even the most pedantic son ever say ‘Hi, Dad, sorry I’m late’ with such density? In reading through this text we get lost among Laon’s intricate tropes. It’s a wonder that Cleocarpus knows what his stepson is trying to say, although he goes right on after this with a speech in praise of sailing and maritime commerce — which might well be placed exactly where it is in the play, and make just as much sense, if Laon’s speech were completely excised. The reason for the discrepancy between these two works of the poet-friends? Krasiński, warts and all, has a fine ear for dialogue, and is able to create a believable, realistic verbal fencing match between the characters of Pankracy and Count Henryk (which we shall omit here, for considerations of space), no thrust or parry of which can be deleted without harming the whole. In Norwid’s play, Laon and Cleocarpus deliver soliloquies, recognising the (unnecessary?) presence of one another merely by waiting for the other to finish his spiel before beginning his own.

Of course, it is not always thus with Norwid’s plays. Passages from Cleopatra and Caesar, Wanda, Zwolon, Krakus, just about any of the plays here included, sparkle with polished repartee. We must also remember that Tyrtaeus is supposed to be a failure as a dramatic work, and whereas the conversation in the garden between Tyrtaeus and Eginea is brilliant, theatrically, the citation of Glückschnell’s words above might well be a veiled ‘note to self’ by Norwid.

norwid and the word

That said, one of the things that occurs to the reader of Norwid’s plays is that there are few Polish poets, certainly none among the Romantics, who pay such close attention to the word and, what we might call for lack of a better term, communication theory. Before we make too great an authority of Glückschnell, we ought to remind ourselves what his character represents. Just as his name suggests, he is after fortune (Glück), and quick! (schnell). No artist himself, he is a promoter, eager to make money by pleasing the audience, hoping, for example, that the serious, failed tragedy of Omegitt’s will not turn the audience away before he can pull them back in with the snappy songs and witty sketches that are slated to follow it. He is not even a competent critic, since, as he admits to another character, he wishes to follow the vacuous popular French author de Fiffraque around a bit to learn from him ‘what we are to think and write’ about the play that he himself has chosen to produce. Glückschnell sins at the other extreme: trafficking in pleasant banalities. Now, whereas plays, produced as they ought to be, on stage or in dramatic reading, do not afford the receptors much luxury to savour deeply every word presented by the poeta doctus, this brief exchange between Zwolon and a peremptory court official might be set forward as an example of the approach to the word that Norwid recommends:

GUARDSMAN

What do we have here? Are you casting spells,

Magician? Drawing runes and warlock wheels

On royal footpaths?

ZWOLON

With great calm.

Those are royal seals.

GUARDSMAN

What?!

ZWOLON

Royal seals. Look closely. Can’t you tell?

GUARDSMAN

No!

ZWOLON

The garden implements all bear that mark.

GUARDSMAN

Inspecting the impressions more closely.

Aha — I see…

ZWOLON

Like God’s word. So it goes:

From quire to quire

It flows on ever higher,

And here it sparks, while there it bursts to flame,

And lower still, its fire

Cheers, and feeds the plain

Still lower with lush green.

And there’s another might — of stone:

A stupid thing that hastes

About the ruts of waste

Where verdure is unseen

And so it mocks the truth with jibing splutter

And quire on quire slips down the crooked gutter.

Pause. He gazes at the sky.

It looks like we’ll have rain again tomorrow.

Goodbye.

He moves off.

The Guardsman sees Zwolon standing near some odd impressions in the dust and jumps to a wild conclusion. Calmly, Zwolon has him look more closely; to pause, and consider the evidence presented before speaking; in short, to take the time to interpret the matter set before him, just as a reader, or critic, ought to bend over a text. The Guardsman — like most of Glückschnell’s audience — is too impatient for that; he wants to consume and move on, not savour and delectate. The conclusion of this passage is a masterpiece of dramatic movement. Zwolon pronounces a brief sentence on ‘God’s word’ — an example of dense, challenging poetry — and when he looks at the flummoxed face of the Guardsman, unable to deal with anything more complicated than pleasantries and hasty charges, he breaks off with a — banal — comment on the weather forecast and walks away.

Norwid is a poet who knows the weight of words. It is no coincidence that two of his most sympathetic characters, two queens: Wanda and Cleopatra, in the plays that bear their names, have periods of silence, of keeping quiet, of not speaking, so long, as a matter of fact, that their subjects and intimates become unnerved. Sometimes, it is better to say nothing than to use speech improperly.8 In two of his plays, Zwolon and Krakus, the nineteenth-century Pole displays an uneasy sensitivity to the possible misuse of speech that predates George Orwell by over half a century. In the first of these, Zobor, a ruthless henchman of his absolute monarch, who hesitates not to bring negotiations to a satisfactory end by underhandedly slaughtering the other side, tells the scribe Stylec how he ought to approach recording what has just happened for posterity:

Describing victory,

Let your descriptions not be niggardly.

Use your imagination. Writing is

An art — these pages are clean canvases.

And as you write, show some liberality —

You are the one creating history —

Be as a trumpet: blaring, thundering,

And your inventions will become the thing

Itself. The writer’s might is chthonic,

Creating… truth. Where would Achilles be

If not for some well-crafted histrionics?

He who controls the past, controls the present and the future as well — for sure. Rakuz, the brutal usurping prince of Norwid’s retelling of the foundational myth of Wawel Castle in Kraków, establishes his own Ministry of Truth. First, he suppresses the historical record. When the cringing Szołom approaches him with his record of the final moments of the king’s life, which contains no explicit decision regarding the succession to the crown of Kraków, Rakuz commands:

You’ll no more touch those writings. Give them here.

For all times in his treasury they’ll be lain,

Despite the fact his will was none too clear,

And failed to indicate an heir by name.

Or, precisely because he failed to indicate an heir by name. If, in his Undivine Comedy, Zygmunt Krasiński predicted the class struggles that were to plague most of the twentieth century, in Krakus and in Zwolon Norwid prophesies the nefarious nature of totalitarianism. Consider how the exchange between Rakuz the usurper and his servile scribe develops following the lines just quoted:

SZOŁOM

When all a man’s strength is well-nigh consumed,

He’s like a candle as it’s burning down —

By this you’ll know the man who knows the runes:

For he can clarify, explain, expound —

O, for example, look here: see what I’d

Inscribed with my own hand next to those words:

‘By this, clearly, Rakuz is signified,’

Although he was awaiting both young lords…

RAKUZ

Such things, if anyone, the runesman can

Unravel — false appearances from truth —

I do not seek the praise of any man.

The truth is my concern alone.

SZOŁOM

In sooth!

RAKUZ

And truth is…?

SZOŁOM

Ah, what is truth?

RAKUZ

Truth is a word.

Whatever you redact, don’t hesitate

To bring to me…

Now, whereas Communism was little more than a word in the nineteenth century, totalitarianism has always been around, and the Warsaw native Cyprian Kamil Norwid was aware of how words can be used to affect, if not change, reality. Surely, the quip of Alexander Pushkin was known to him,9 who warned off Western Europeans from intervening in Poland’s uprising against Tsarist Russia with his condescending description of the war for national liberation as a mere ‘quarrel between brothers.’

But words can also be used as proper weapons, when they are in the service of truth. Krakus returns to Kraków and slays the dragon that Rakuz hardly dared approach, not with the strength of his arm, but by words, as the mystical Spring taught him during his rest in the Sapphire Grotto:

SPRING

Then no more sleep —

This wisdom keep

Ever present in your mind:

Poems can heal

And bite like steel.

Strike the dragon with such rhymes!

And here we have the true import of Norwid’s writing: it is in service of something else, something beyond literature. Chwila myśli [AMomentofThought], that early poem in dramatic form with which we open our collection, begins with a young man not understanding the anxiety that grips him. He wants to be a writer, but wonders if he has the talent to succeed as he would like, and if not, will he agree to be ‘drawn and quartered’ for money, writing the sort of things that the Glückschnells of the world pay good money to produce, and good money to consume? What is he to do? The answer to his anxious queries in that cold garret comes with the cries of some children in the building: ‘Mama, mama, we’re hungry! Give us bread!’ Norwid is too good a writer to have light-bulbs popping over the character’s head here; he is at first obtuse, responding to the cries of the hungry children with a clueless, self-centred thought: ‘They suffer in the flesh, and I, in spirit.’ Now, whether or not the sufferings of the soul can be as acute as those of the flesh, this is a rather cold and oblivious thing to say to the father of the children, who had just finished describing their plight in the winter. A Moment of Thought is exactly what its title suggests: a brief meditation that suggests rather than provides a developed answer to the dramatic conflict — in this case, what is the role, or even sense, of art in a world where hungry children freeze in winter? And although no definitive answer is given, one is certainly suggested: Whatever you do, whatever you busy yourself with, help others, if only you can. Norwid’s youth is worried about becoming an author. But what does writing matter? What he should be worried about is being a good man.

In Krytyka [Criticism] another of these brief dramatic sketches in verse, a similar question is put to the eponymous character who has just denigrated the use of modern, northern European models for artworks depicting Biblical scenes. The Secretary of the journal for which the Critic writes counters with words that might be considered Norwid’s own:

SECRETARY

One more question, if I may:

Now, is the goal of artworks to disguise

The word, or to reveal it to our eyes?

For truth is born each day; we’re ever turning

A new page, and with care: we’re ever learning

— Through nineteen centuries — that we’re to seek

In each and every person that we meet,

Though they be deeply hidden — Cross and gall,

Nail-head and tomb and glory’s ray, and all

The grand account of our salvation — stippled,

Shaded and bright, in both hale and cripple.

How else can virtue speak unto our heart?

Although the clueless Critic, satirised by Norwid, responds with his familiar ‘What sense, in that case, has the critic’s art?’ the message of the Secretary is as clear and simple as any parable from the New Testament: what is the ‘truth’ of an authentic setting, or a search for Middle Eastern / Semitic human types for Biblical paintings, in comparison to the truth defended by the Secretary: we are all of us children of God, and we are to see Christ in everyone we meet, not just those who look like Him on the outside. Norwid’s critic would find a lot to object to in Gaugin’s Tahitian Holy Families, while Norwid and his Secretary, on the other hand, would consider them greater than mere paintings: icons, which visually and immediately present a profound theological lesson concerning God’s love for us, all of us, and the love and respect He expects us to have for one another.

norwid, criticism, and truth

Speaking of critics, in general, Norwid has few kind words to offer them. The master-builder Psymmachus sums them up thus in Cleopatra and Caesar:

O, there’s no lack of critics, but the learned?

The competent ones? It’s like aboard ship:

Those without sea-legs tumble to the rail

To bark into the waves… their morning meal.

So much for critics. They know how to clap

Or piss at one’s foundations. Spasmatics

With bladders full…

And in the play In the Wings, Norwid repeats the familiar canard of the critic as a failed writer — unable to be creative himself, he criticises the creativity of others. This argument, while it overlooks Samuel Johnson’s bon mot, that one needn’t be a joiner in order to tell when a table is crooked, is not the main philosophical reason behind Norwid’s disdain for critics. It is, rather, their lack of charity. As he puts it in the brief introduction to Krakus:

Today’s critics, dispossessed of that informality, simple, not to say Christian, which permits a person to respond directly to direct questions, are very defective in that first great virtue of brokering and mediating between works of literature and the readership. One might think that they preserve unto themselves a mandate of casual and persistent review and censorship, at the cost, indeed, of readers to whom the chief principles and truth of the literary art are unfamiliar — and who thus are presented merely with the particular works or reputations of such persons as they have permitted to exist!

As Norwid sees it, the critic has a ‘sacred’ obligation to help those who need him, the readers as defined above, and not to use the texts they criticise in order to further their own agenda; pulling others down, so as to appear to be above them. It is the careful critic who is needed, one who patiently bends over the given text, and after sensitive study, is able to extract the one important thing from it, the truth, for those who can’t access it otherwise.

Here we find another point of contact with Hopkins. The critics castigated by Norwid are like the interpreters of Sibylline oracles: the truth is there, but they are unable to suss it out. In Wanda, after Rytyger tosses the chalice he’d been drinking from into the woods, and an aerie of eagles take wing, the German runesmen opine:

The queen shall fall in love, and with such might

Not seen since ages hoary.

Four eagles, at your throw, took flight.

Great shall be her glory.

She’ll fall in love, and bathe her body white.

Ironically, their interpretation is correct, but in the most essential sense, they get it all horribly wrong. Wanda shall fall in love indeed — but with her nation, not with Rytyger. She will bathe her body white, but not in preparation for her nuptials, rather, she will cast herself into the Vistula, self-immolating in Christ-like fashion, to save her people the Wiślanie, and, by extension, Poland, from becoming subsumed into the German element through an unconsidered marriage to the German prince.

The truth is a slippery thing, but it is perceptible to those who follow it with humility. This is effectively borne out in that scene from Wanda’s twin Cracovian tragedy, Krakus. When Krakus, spurned and wounded by his own power-hungry brother and left in the forest, returns incognito to deal with the dragon plaguing the royal castle of Wawel, he finds his brother Rakuz, exhausted with watching, asleep in a chair. Gazing at him tenderly, from the new heights of his sublime, mystical enlightenment, Krakus whispers: ‘Mere presence at the crucial hour — what dare / Man hazard without peace, conscience, and prayer?’ Thinking to approach his brother, he decides better of it — let him rest, worn out, as Krakus mistakenly infers, with weeping for their dead father — and goes off to slay the dragon. The ironic thing is that these very same words were on the lips of Rakuz just before he dozed. However, he continues them, confessing that they are ‘Three things, of which [he’s] never had the pleasure / Of personal acquaintance…’

The truth, like our conscience, is inborn in all of us. That is what is suggested by this curious repetition. What we do with the truth makes all the difference, in our own lives, and in the life of the world, to say nothing of our eternal destiny. Norwid here is dramatically presenting the lesson given us on faith by St James. Faith? Without works? ‘Thou believest that there is one God. Thou dost well: the devils also believe and tremble.’10

norwid and the dantean approach to literature

At the base of Norwid’s writing is the Christian conviction that this life is not all there is, that happiness in this life is not man’s supreme aim, and that the eternal destiny of man, which is a gift from God, also carries with it responsibilities. This is what, in shorthand, we might call the Dantean tradition, after its greatest literary practitioner, although it can be found, of course, before theDivine Comedy and after, as it stretches into our own day — in the works of T.S. Eliot and Jan Zahradníček, to give but two examples. And so, in Zwolon, while Norwid does not push aside ideas of justice here and now (his ‘improvisation’ on the two colours — red and white — is a yearning for a just and free Poland) it is not something that should be fought for at all costs. There are more important considerations. The character of Szołom, whom we meet up with in Krakus as well as here,11 is a stirrer-up of strife, a person playing two sides of the same game for his own benefit, or, worse, the benefit of the destructive powers of the air. It is for this reason that, after the defeat of the rebels, when Szołom is skipping round Zwolon, seeking to engage him in conversation, alternatively fawning over and tempting him (if subtly), Zwolon first ignores him, and at last asks him ‘what is your name?’ — approaching the character as an exorcist might. Szołom, ‘bound,’ reveals his name (he is a servant of Spirit — but which ‘Spirit?’) and disappears.

Again, it’s not enough to recognise the truth; one must also use it, correctly. Gaius Valerius, in the dramatic poem Słodycz [Sweetness] is not necessarily an evil man. He keeps Julia Murtia imprisoned not because he is a sadist deriving pleasure from tormenting her. Rather, he is busied with an experiment: he has heard of these Christians, and wants to find out what makes them tick:

Should I declare her Christian, she’s undone.

She’s executed and… what would I have won?

Will that in some way heighten my control

Over her? Or will it transform her soul

Into a flower (if Plato is proved

Correct) — and if so, can a flower be moved?

[…]

… Where do these Christians get that inner strength?

I’ve seen troops hopelessly beset, veterans

Of ancient legions; I’ve known gladiators…

It’s something more than bravery —

He’s not after her death, he’s after understanding. However, when that opportunity is presented to him, in a dream, when St Paul appears to him, he reveals his true colours:

Old man — you, in that cloak of red you wear,

Barefoot, with flashing sword there at your side

Where we’ve but dark and empty pleats, who cried

That I might be entangled too — speak on!

I’m listening…

ST PAUL

In Gaius Veletrius’ dream.

The grace over which none

Of your fierce tormentings can prevail

I can give you — and with it, you might heal.

But why do you seek it?

GAIUS VELETRIUS

Quickly, unconsciously.

So I might overcome

Her!

ST PAUL

Touching Gaius Veletrius’ shoulder with the point of his sword.

Julia Murtia has died.

He sought it not for his own salvation, or to become one with her. He sought it as some unvanquishable talisman, with which he might overcome her — and in the end she overcomes him, by escaping in death to a greater freedom than he can imagine; a freedom he himself will never taste at his own passing, since he refused the one opportunity afforded him to grasp it. His death will lead to a deeper prison than hers in the Vestals’ gaol. For we live in an eternal moment of decision — as Eliot will say, each of our acts, however trivial, is a moral decision, for good or evil, with eternal consequences. The thrust of Norwid’s dramatic works, like the Divine Comedy of Dante, is to prompt us to choose wisely, so that we should not end up like his Roman high

priest.

notes on the individual plays

Though I hope not to become another Glückschnell, who would tell the reader ‘how we are to judge and how we are to write about’ the plays included in these Dramatic Works of Cyprian Kamil Norwid, I still would like to present a few short paragraphs on each of them, so as to set them in a more particular context than the general thoughts we have presented so far.

the shorter works

For most Poles, Norwid is above all a lyric poet. He seems to have approached the theatre with timid steps, as, in our chronological arrangement, we note that the first four plays are short sketches — scenes or tiny dramas (a genre initiated among the Slavs by Pushkin with his Little Tragedies), which can just as well be considered lyric poems in dramatic form,12 as small dramas in verse: A Moment of Thought, Sweetness, Auto-da-fé and Criticism.

The Christian themes present in Norwid’s poetry, which we have noted above, can already be found in these first tentative dramatic sketches. Not only is Sweetness a story of Christian patience usque ad sanguinem, but A Moment of Thought is as well, even though it does not end with a definitive picture of the Youth’s next step, concludes with an expression of the sense of the universe, which indicates the path that will lead him to his answer:

We’ve still learned nothing. Nothing but the cross

That stretches wide its arms old folks to greet,

The youth to bless, and, bending through the rent

Clouds, peers to spell out from the children’s eyes

Whether these ribbons, which so thickly flow

Will be worth anything? Or disappear?

No! They won’t disappear. For deep inside

As long as — in thought, not in screams — grows

Pain, it shall burst into bloom, a thorny bow

To ply the heartstrings of all who live below!

As individual as Norwid is, he does emerge from a tradition that cannot but leave its mark on him. The tradition to which I refer here is not just Christian culture, but the works of the first generation of Polish Romantics. In Adam Mickiewicz’s Forefathers’ Eve, Part III, the Promethean hero Konrad learns that, even if we cannot fly before the throne of God to solve the problems of the world, we can make the world a slightly better place by small acts of charity. His selling of his signet ring as he heads off into exile in Russia, with half of the proceeds to go to the poor, and half for Masses on behalf of the souls suffering in Purgatory, is a concrete act of charity which outweighs by a thousandfold all the bombastic cosmic plans of saving his nation, which are doomed to failure from the start. Norwid learns from this, as here, his hero slowly comes to understand that our mere sensitivity to suffering prods us to ask questions and try to help others, and this, like Konrad’s humble gift of his ring, is sometimes quite enough.

A Moment of Thought is a work in which the main character asks himself what can fame, and writing itself, be worth in a world so full of human suffering. This questioning of the sense of writing (when there are so many more important things to do) is part of a current of self-criticism that runs through Norwid’s plays. It is taken up in Auto-da-fé, in which the main character, a writer named Protazy, uses books as kindling. At one point, considering the glut of printed works in the world (one can only wonder what he would think of our days of print-on-demand and electronic self-publishing!), he muses:

I don’t understand

This strange world any more. Each writer sets

A pen in his wife’s mouth; talking with friends

He thinks: ‘There’s a new page!’ And off he jets

To write it down. Men are no longer ends

In themselves, but merely means to spill some ink!

And for what? For a plasma ball that sparks,

Spitting some dim electrodes in the dark.

Writers, he suggests, are so in love with writing, that it elbows out living. People are not to be loved, experiences are not to be savoured, they are all but the raw material of literature. It’s hard not to agree that books written in this fashion are better tossed into the stove than set on the shelf.

This thought, too, is derived from an earlier work, the Undivine Comedy of Norwid’s older friend Zygmunt Krasiński. There, Count Henryk, a poet, is so enamoured of the make-believe world of the poetic ideal, that he drives his real family — a real wife and a real son — into tragedy on account of his mania. Norwid’s Protazy, unlike Count Henryk, is clear-eyed. Though he may have his own problems to deal with in respect to how he treats people (and how he thinks of himself) his burning of the books seems an almost subconscious desire on Norwid’s part to put art in its place.

Yet it is not only poets and writers who are to blame here. In Criticism, Norwid sounds a theme that he will repeat in Auto-da-fé: critics and readers rarely approach a book on its own merits. Rather, they seek out works, authors, and themes which validate their own way of thinking. In the former, the critic responds to criticism of his assessment of a book, which he judged not on its artistic merits, but on the ‘lesson’ it presents:

CRITIC

What? Virtue

Is not sufficient for a worthy book?

SOMEONE

Perhaps, but, for a work of fiction? Look —

Would you call that a novel, or a chart

Of your own views?

CRITIC

What else is the critic’s art?

And in the latter, Protazy, again:

As the lightning splits the air,

Leaping great distances to spread its light,

So, people say, is print. They may be right,

But when a person takes a book back home

And sits down on his chair or in his bed

To slice through page-ends with his knife, instead

Of reading, he but searches for his own

Thoughts in the author’s words, which, should he find,

He’s satisfied. This reader is a kind

Of writer, but a lazy one; from this,

It’s plain to see that readers… don’t exist!

In this, the little dramas are most similar to dramatised lyrics: there is not space enough for too many themes; most often, it is one thought, one idea, that the poet seeks to delve into with a pithy directness.

the 1002nd night

This early play, a comedy, is one of Norwid’s few completely finished works for the stage. With it, he introduces a motif that will accompany his dramatic writing to the very end: that of a hidden truth, masquerading, concealment. On the one hand, this reveals Norwid to be a very nineteenth-century artist, naively operatic, in the manner of Mozart/Da Ponte’s Marriage of Figaro or Shakespeare’s Two Gentlemen of Verona.

The Count (why are these people always counts?) believes that the mysterious woman who has arrived at the inn where he is staying in Verona is the same one who, as he understands it, rejected his proposal of love in a very insulting way — by sending him a letter that ends with ‘and here’s my reply —’ which reply is his own letter, returned to him. (We pass by the fact that a proposal of love sent to a woman by letter is itself a rather clumsy thing, if not adolescent). The woman wishes to look out on a storm from the window of the room occupied by the Count, in which she once stayed herself, and the Count plans on taking his revenge by hiding in the closet and then leaping out to confront her and her supposed husband when they arrive:

I — shall emerge, calmly, coldly — no exaggerations — and ask her to introduce me to her husband. I’ll fill in whatever she leaves out… with a smile… And then I’ll wish her bon voyage…

We’ll change the play into a still, deep, drama, or a casual comedy… at any rate… alea iacta est…

Some Caesar! At this point, we are beginning to wonder if the Count is fourteen…

He will confront her with… the second half of her letter, which she, distractedly, left in that very room, and which he — by improbable coincidence — found there… And yet Norwid shows a surprisingly mature theatrical sensibility by veering the story left at the very last moment. For when the Count leaps out crying triumphantly ‘A masterpiece of recklessness…!’ his voice dies off in embarrassment, for — the woman is a complete stranger. The masterpiece of recklessness turns out to be not the letter ‘she’ wrote him, but the opera buffa trap he laid. And thus, a play which seemed to be rolling in the well-oiled grooves of convention, with improbabilities that do not necessarily arise in a logical fashion, and melodramatic elements such as the closet-trap, are completely destroyed. Melodrama becomes absurdity, and in a way that underscores the primacy of unpredictable, real life over the contrived imagination that wishes to control it.

zwolon

If we were providing more than just the titles of the plays for dividers in these notes, here we would probably have something like ‘Zwolon, or a Guided Tour of the Polish Romantic Stage.’ For it is in this unfinished drama — still perhaps the most intriguing of Norwid’s works for the stage — where the great, idiosyncratic poet uncovers to our eyes the sources of his inspiration. Zwolon contains so many palpable allusions to the theatrical works of Mickiewicz, Słowacki, and Krasiński, topped off with Byron, as to seem something of a show-piece of a virtuoso musician, setting forth the range and variety of his skills.

It is a veritable anthology of influences.13 We have a meeting of conspirators under the leadership of a timid cénacle chief such as we find in Słowacki’s Kordian, a blind boy-poet of the Orcio type (an allusion to Krasiński’s Undivine Comedy — although, it seems, this blind boy is not doomed to fade away; he triumphs in the end), a nod to the very roots of the great-souled Byronic traditions with the addition of a sardonic character named Harold, and — most tellingly — a long soliloquy spoken by the main character, Zwolon, which is a clear homage to the greatest improvisations of the Polish Monumental stage: Kordian’s soliloquy on Mont Blanc and — of course, the greatest of them all — Konrad’s fierce, despairing (and wrongheaded) diatribe against God in Part III of Forefathers’ Eve.

However, Norwid’s Zwolon differs from the romantic heroes such as Konrad and Kordian in this, that heisnot a rebel. This should not be misunderstood as to suggest that Norwid was any sort of loyalist. Nothing can be farther from the truth. Norwid was no less an advocate of national self-determination, yearning after the independence of partitioned Poland, than the great Romantics, whose exile from the fatherland he shared. But whether it be because Norwid came of a later generation that witnessed (as a child and as an adult) two armed uprisings end in tragedy, or because of his authentic Christian faith, which, while not necessarily quiescent or pacifistic, preferred the arms of the Spirit to those produced by armament factories, he longs for the reconquest of Polish independence through victory in the moral struggle. And so, to give but one lyrical passage from Zwolon’s ‘great improvisation,’ striking in its similarity to the more exalted bits of ‘Chopin’s Grand Piano’ with its longing for a Poland of ‘transfigured wheelwrights,’ where Christ rules ‘incarnate upon Tabor,’ Norwid’s hero exults in a mystical vision of his country:

From her I lived, and lived with her. Her I now wish to see

So perfect, and full of being, to be

Like the nation’s eagle, in a flash, like a young thing

Of another world… leading the rushing throng,

And psalter-in-hand, leading the nation in song!

Like streaming choruses, with rhythm angelic,

Aquiline, lyric,

From Lech to Lech the national glory

And she, with outstretched hand, toward the wings falling there,

Gathering from the air

The echoes of history,

That might tangle-twine in wreaths, of this land!…

Again, this is not quiescence by any measure. Norwid castigates evil directly where he finds it, and the very fact that the revolutionary party succeeds in violently overthrowing the unnamed, quasi-tyrannical king at the conclusion of the play is evidence enough of his understanding that, yes, at times, violence can be justified (as in a just war) to achieve moral aims. But just as the definition of a just war requires a careful ascertainment of war aims before the battle is joined, so in Zwolon Norwid cautions the hotheads against mistaking simple adrenaline and bloodlust for righteous ire. After the chilling character Bolej is introduced, who cannot sleep because of his desire to slash and kill and burn, Zwolon appeals to the crowd:

ZWOLON

Gesturing at Bolej.

This young man, nourished, as he says, on gore,

Is no son of freedom — he’s nothing more

Than judgement’s slave. And you, and those

Beneath thatflag unfurled — which of you knows

Exactly what it means?

SZOŁOM

Traitor! Be gone!

His words would douse the ardour of the throng!

ZWOLON

Citizens! Citizens — but of what state?

The fatherland, or despair?

SOME

Ah — hear him prate!

ZWOLON

For I’m not sure — you’re rushing off to die;

Is there any among you fit to seek

Life? Everyone would die for freedom’s sake,

As if only the tomb were liberty,

And any sort of perishing, the gate

To immortality. Ah, but revenge

And liberty — these are quite different ends!

And often, when the two are so entwined,

And vengeance is achieved, avengers find

They’ve lost their freedom…

The argument is both practical and Christian. Practical, in that one can never tell whether violence may not lead to even greater oppression (of which the recent history of Norwid’s Poland offered ample evidence) and Christian, in that it reminds the mob of the fact that their enemies are people too. The laws of God must always be respected, especially in cases where one finds oneself in a desperate situation that calls for violent action. In other words, there are things even more important than national independence. This sentiment veers quite near heresy in the ears of the earlier generation of Polish Romantics, and it is no surprise that Zwolon’s words not only fall on deaf ears, they arouse the people against him — and this will eventually lead to his death.

Norwid’s Zwolon, again, is no Byronic rebel. He is, rather, a prophetic spokesman of Christian truth — a representative of the King of Kings, the Order of all orders, against which Mickiewicz, boldly and beautifully, had his Konrad arise on behalf of justice for the nation he loves.

Zwolon’s diametrical opposite in the play is the character named Szołom. Just as Zwolon’s name suggests his character as one ‘called, elected,’ so does that of Szołom, from the verb oszołomić [‘stun, bewilder,’ by extension: ‘lead astray by obfuscation’], aptly summing up the character of this figure, who appears in Norwid’s works like the wandering Jew. In both this play and the later Krakus, Szołom is a servile tool of power, more than willing to set aside morality in order to serve a strongman. In Zwolon, his character is that of an agent provocateur: he stirs up the rabble to their rebellion in order to give the King an excuse to set his realm in iron order by moving strongly against an uprising. It is significant that, towards the end of the play, when everything seems to have gone wrong for him, the rat leaps from the sinking ship. Coming across Zwolon, he starts to skip round him with blandishments:

SZOŁOM

In travelling attire.

What have they won for us? Ruins on all sides,

Great man — blood, shame, and poverty, and waste!

In vain I begged, yes, in vain I cried

‘Brothers! I like not the look on their faces,

Those fighting boys!’ Destruction and disgrace!

Pause. He continues following the silent Zwolon, peering continually into his eyes.

There was more courage by far in negation

Than in stoking just ire into the elation

Of bloody vengeance! Knowledge directs lives

Better than swords — a mere temptation

For children! What are swords? Are kitchen knives

Not made of the same steel? And so, why not

Make flags of tablecloths, with which to march

To cheering crowds through a triumphal arch

For having nobly with a pork-chop fought?

Pause. Szołom continues to skip at Zwolon’s side, glancing up at his face

beneath the brim of his hat.

Am I not right, sir? Wise men know it’s all

Spirit, yes, the Spirit’s what it’s all about!

But those men! They’re unlearned — like some pagan rout!

And in the end, upon the learned falls

The blame, and we, what can we do but bear it?

With a sad gesture, he halts Zwolon.

So let us suffer. Meanwhile, in that spirit,

I bid farewell to you.

ZWOLON

Tell me your name.

SZOŁOM

Dodging aside.

Szołom, a servant of the Spirit.

What is worth pointing out here is not so much the cringing nature of Szołom as Zwolon’s calm, though stern, engagement with the lackey. As mentioned above, ‘Tell me your name’ is an allusion to the rite of exorcism. Commanded to reveal his identity, the demonic spirit (what ‘Spirit,’ indeed, does a wretch like Szołom serve?) falls under the control of the exorcist, who moves on to expel him. Szołom’s sudden disappearance after telling his name — even though he previously announced his desire to leave, after his attempt at self-justification — sets this scene in the context of the exorcism of Mickiewicz’s Konrad by Fr Piotr. And once more, the distinction between Norwid’s Christian hero and the rebels of the earlier Romantics is set in high relief.

the kraków plays

In 1842, on his way to further artistic studies in western Europe, Norwid passed through Kraków. As Kazimierz Wyka tells us:

Such a journey of several months constituted the realisation of the programme of the Romantic grand tour […] Due to different political conditions, this programme could be realised by the first generation of Polish Romantics [such as Mickiewicz, Słowacki and Krasiński…] in a manner different to that in which it was by the second romantic generation, to which Norwid belonged. […] The former were still capable of truly grand romantic voyages — one example of which is presented by the second act of Kordian: Italy, Rome, London, Mont Blanc. […] The Romantics at home in Poland could not indulge in such journeys because of political concerns — ever-present police observation, the necessity of obtaining a foreign passport, and also monetary worries. […] All that remained in place of this was to wander about the country. […] A trip through Poland, however, had its own justifications and nomenclature. Because Romanticism awakened lively interest in the historical past of the country as well as the material relics and other testimonies to that history — called the fatherland’s antiquities — these journeys were known as ‘travels into antiquity.’14

No other region of Poland presented the ‘traveller into antiquity’ with so many witnesses and relics to the historical past of Poland than Kraków. The mediaeval core of the city, crowned by Wawel, that royal necropolis and treasury, as well as traditions such as the Lajkonik, impressed Norwid to such an extent that, in Wyka’s estimation, he becomes the first of a long line of Cracovian poets, including Wyspiański, Czyżewski and Gałczyński, who poeticised the city and its celebrations.15

Among the relics in the region of Kraków are the ancient mounds of Krak and Wanda. These neolithic tumuli have been associated from ancient times with the pre-Christian rulers of the Wiślanie: Wanda, who rejected the hand of a German prince in order to guarantee the national autonomy of her people, and Krak, who founded the city that bears his name after overcoming a dragon laying waste to the surrounding countryside. These mounds inspired Norwid so, that he not only created two of his most successful, and complete, dramas, Wanda and Krakus, the Unknown Prince, but dedicated the first, in gratitude — not to any person, but to the mound of Wanda itself! This very fact opens our eyes to his spiritual kinship with Wyspiański, who also testified to his love of the ‘stones’ of Kraków. As Wyka points out, ‘After all, both of these compositions close with an apotheosis of place, apotheoses played out in a manner that cannot but have attracted Wyspiański, as they are in such great agreement with his own theatrical imagination.’16

Who can say if Wyspiański’s great theatrical triumph Acropolis — in which there are no human characters, but only vivified statues and tapestries from the Wawel palace and cathedral complex, to say nothing of the enlivened tomb of St Stanisław, which (or ‘who?’) falls upon King Bolesław Śmiały in Wyspiański’s retelling of that conflict — would have come about, if it were not for the anthropomorphosised characters of the Threshold and the Spring, who play such a key role in the mystical scenes of Krakus?

This play, which, as Norwid himself notes, forms a dramatic diptych with Wanda, provides us with a glimpse into the poet’s theoretical musings. In his introduction to Krakus, Norwid defines tragedy thus:

As far as I am personally concerned, I believe tragedy to be the making apparent of the fatal nature of history, society, the nation, or the age proper thereunto. Consequent to this definition, it plays an auxiliary role in the progress of morality and truth. For this reason, it is no wonder at all that tragedy could, and indeed had to, be possessed of an almost ritual gravity.

These words should be borne in mind when considering Krakus’ triumph over the dragon — defined by the elderly Hermit (a nod, again, towards Słowacki’s Balladyna) as a progeny of ‘the first snake, by Virgin’s foot / […] crushed; / your dragon’s merely an offshoot / Of that first evil,’ where, it is not with steel, but with grace and virtue — and song — and truth — that the victory is won:

KRAKUS

Song.

Come forth! Now! By the faith of faiths

I conjure you, who gnaw the soul —

Your spell is gone with your last breaths;

My spell, it is no spell at all!

God knows how much sin, foul and black

Impels me here to sling this word

Into your face — my only sword

This lyre; this song — my only act —

My song is now no song at all!

Although this play is set in the ancient pagan past, and we do not witness Krakus’ baptism, it is the ‘faith of faiths’ — Christianity — that triumphs over the enemy of all mankind, the devil; Rakuz, who remains in paganism (even after the victory over the dragon) is not only impotent in face of the evil, but becomes the evil after the death of the dragon by his jealous murder of his own brother. Krakus, who slays the snake, triumphs as a Christian hero.

Likewise, Wanda, a princess of an even earlier age than Krak, does not merely commit suicide in order to avoid an unwelcome marriage; in Norwid’s retelling of the story, at the key moment of the drama, she is granted a vision of Christ’s sacrifice on Calvary, and this indicates to her what she is to do. Her death is not a suicide, it is a sacrifice on behalf of the good of her people, and thus raises her to the dignity of a Christian martyr:

WANDA

My good people — I’ve seen above our land

God’s immense shadow, like a straight road, run;

It was but the shadow of His hand,

And that hand — pierced — for through the palm the sun

Shone unimpeded… Staring like a bird

Flying in darkness toward that chink of light,

Suddenly, something in my spirit stirred

To a sure knowledge of what I must do…

She takes a candle from the hand of Piast, and ascends the pile.

Then, more quietly: