11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

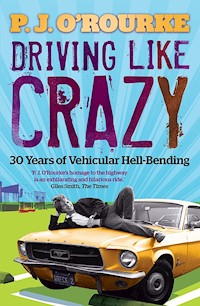

'America's greatest prose comedian' -- Anthony Quinn, Sunday Times Growing up as the son of a car dealer in Ohio, P. J. O'Rourke, 'the funniest writer in America', has always been crazy about cars. Driving Like Crazy revels in his love for all things vehicular. Jump in and buckle-up. P. J. O'Rourke delivers his rapid-fire wit from the driver's seat of Buicks, Land Rovers, Harley-Davidsons and at least one Soviet army surplus truck. Driving Like Crazy is a hilarious collection of fender-bending pieces that career along at O'Rourke's full-throttle, breakneck Gonzo best... Praise for Driving Like Crazy: 'A rollicking ride through three decades of O'Rourke's car journalism, combining classic articles and new material with his trademark merciless skewering of liberal niceties and political correctness at every turn.' Philip Sherwell, Sunday Telegraph 'P. J. O'Rourke's homage to the highway is an exhilarating and hilarious ride... Nobody can argue with the fantastic forward rush of O'Rourke's prose... it's why you're glad you went along for the ride.' Giles Smith, The Times 'O'Rourke is America's funniest writer, having stolen the flag of Gonzo from Hunter S. Thompson... The pieces make great travel writing - stripped-down, yet evocative. O'Rourke fans will find plenty to enjoy in Driving Like Crazy.' Stephen Price, Sunday Business Post 'Whatever the topic, P J O'Rourke is equal parts hilarity and extremity.' Daily Telegraph

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

DRIVING LIKE CRAZY

P. J. O’Rourke is the author of fifteen books which have been translated into a dozen languages worldwide, including Parliament of Whores and Give War a Chance, both of which were New York Times bestsellers. When not on the road, P. J. O’Rourke divides his time between New Hampshire and Washington, DC.

ALSO BY P. J. O’ROURKE

Ferrari Refutes the Decline of The West

Modern Manners

The Bachelor Home Companion

Republican Party Reptile

Holidays in Hell

Parliament of Whores

Give War a Chance

All the Trouble in the World

Age and Guile Beat Youth, Innocence, and a Bad Haircut

The American Spectator’s Enemies List

Eat the Rich

The CEO of the Sofa

Peace Kills

On the Wealth of Nations

First published in the United States of America in 2009by Grove Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in hardback in 2009 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2010by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © P. J. O’Rourke, 2009

The moral right of P. J. O’Rourke to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978 1 84887 337 7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn imprint of Grove Atlantic LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To David E. Davis Jr.Boss, mentor, road trip comrade, hunting companion,and—first, last, and always—friend

We drive our cars because they make us free. With cars we need not wait in airline terminals, or travel only where the railway tracks go. Governments detest our cars: they give us too much freedom. How do you control people who can climb into a car at any hour of the day or night and drive to who knows where?

— D.E.D. Jr.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Introduction: The End of the American Car

1 How to Drive Fast on Drugs While Getting Your Wing-Wang Squeezed and Not Spill Your Drink

2 How to Drive Fast When the Drugs Are Mostly Lipitor, the Wing-Wang Needs More Squeezing Than It Used to Before It Gets the Idea, and Spilling Your Drink Is No Problem If You Keep the Sippy Cups from When Your Kids Were Toddlers and Leave the Baby Seat in the Back Seat so that When You Get Pulled Over You Look Like a Perfectly Innocent Grandparent

3 Sgt. Dynaflo’s Last Patrol

4 NASCAR Was Discovered By Me

5 The Rolling Organ Donors Motorcycle Club

6 “Come On Over to My House—We’re Gonna Jump Off the Roof!”

7 A Test of Men and Machines That We Flunked

8 A Better Land Than This

9 Getting Wrecked

10 Keep Your Eyes Off the Road 101

11 Comparative Jeepology

12 Taking My Baby for a Ride

13 ReinCARnation

14 The Geezers’ Grand Prix

15 Call for a New National Park

16 A Ride to the Funny Farm in a Special Needs Station Wagon Complete with Booby Hatch

17 Big Love

18 The Other End of the American Car

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Car journalism is not a solitary artistic endeavor. Obviously. You need a car to write about cars. And if that car is going to be more than four inches long and do something beside roll across the playroom floor for the amusement of my five-yearold son, Buster, then it has to be made by people other than me. Nor is there much that’s artistic about car journalism. Cars are a broad subject with all sorts of sociological, political, and even aesthetic ramifications. But a car is still a car. And there are only so many ways to say “some lunk did something in a clunker.” Thus there is a certain strain upon the language in car journalism. Take the accelerator just for instance. This must be pressed hundreds of times in even a cursory test of a car. As a result, to press the accelerator becomes:

Put the pedal to the metal

Push the go-fast pump

Lead foot it

Slip it the big shoe

Give it the boot

Give it some Welly

Stand on it

Crank it up

Ramp it up

Gin it up

Wind the speedometer . . . the tach . . . the gears

Wind it up like a Hong Kong wristwatch

Drop the bottle and grab the throttle

Floor it

And so forth. For this I apologize to the reader. And to the extent that such euphuistic rodomontade does not drive you crazy in the following pages, credit must be given to car journalism’s editors. Credit must also be given to fellow car journalists, car jockeys, and car nuts who can be counted upon for genuinely clever turns of phrase, which I can be counted on to swipe.

For some reason automobiles attract good people, the kind of people with whom you’d gladly go on road trips. And that’s the secret right there. You need a car to go on a road trip, and the kind of people you wouldn’t take on a road trip aren’t in the car.

Over the past thirty-odd years I’ve had the pleasure of going on road trips with all sorts of good people. Many are named in the text and more are named below. But I have neither the space nor the memory left to list them all. My apologies to anyone whom I’ve forgotten. I promise to pick you up if the Obama administration reduces you to hitchhiking on your road trips.

At Car and Driver and Automobile there variously are and were David E. Davis Jr., Jeannie Davis, Jim Williams, Brock Yates, Bruce McCall, Humphrey Sutton, William Jeans, Don Sherman, Patrick Bedard, Don Coulter, Michael Jordan, Mike Knepper, John Phillips, Kathy Hoy, Jean Lindamood/Jennings, Csaba Csere, Rich Ceppos, Aaron Kiley, Larry Griffin, Philip Llewellin, Harriet Stemberger, Trant Jarman, Greg Jarem, Mark Gilles, and Bill Neale. They can drive like crazy, every one of them.

At Esquire there were Terry McDonell and David Hirshey, the last two Esquire editors worthy of having the publication attach itself to their names.

And at Forbes FYI there was the inimitable Christopher Buckley who founded FYI because his father’s publication, National Review, did not devote adequate space to good food, good drink, good cars, and high living. Thus the question was raised, “What the hell are conservatives conserving?” At FYI Christopher had, fittingly for a conservative, two right hands: Patrick Cooke and Thomas Jackson. Let me shake (not stir) them both.

This book is a mixture of old things and new, not to say a mishmash. Mostly it’s a collection of car journalism from 1977 to the present, a sort of social history with all the social science crap left out. I’ve reworked many of the pieces because the writing—how to put this gently to myself?—sucked. I may not have become a better writer over the years but I’ve become a less bumptious and annoying one, I think. Also many of the original articles dealt at length with then-current minutiae that now has to be explained or, better, deleted. A couple manuscripts (especially “The Rolling Organ Donors Motorcycle Club”) were so bad that my old tear sheets served as little more than aide-mémoirs for the present chapters.

Anyway, to give the publishing history that is required by copyright law or publishers’ custom or some damn thing, the aforementioned motorcycle saga, the journal of a trip across America in a 1956 Buick, the story of Rent-A-Wreck, the tale of an off-road drive from Canada to Mexico, my record of discovering Jeep worship in the Philippines, the log of my trudge to Denver in a station wagon full of children, and the first two parts of the Baja memoirs were originally published in Car and Driver.

The third and most disaster-filled saga of the Baja ran in Esquire about the time that Terry McDonell and David Hirshey were getting out of there. The whole article is about what a godforsaken, star-crossed hell the Baja is, and some idiot from the Esquire promotion department called to ask me if I could write a sidebar about wonderful places to stay and fun things to do there.

The piece on NASCAR appeared in Rolling Stone, also under the editorship of Terry McDonell.

Automobile published the essays about buying a family car and about traveling across India in a Disco II.

Forbes FYI printed the description of the California Mille where the Fangio Chevy was codriven by Fred Schroeder, who was the world’s bravest investment banker until collateralized debt obligations and credit swaps came around and showed that other bankers were more foolhardy than he. The California Mille is the brainchild of the estimable Martin Swig, whose car nut credentials can be summed up in the following anecdote: I was looking for the proper model designation of the Tatra T87, the Czech car from which Ferdinand Porsche stole the Volkswagen design. The Tatra looks like an over-scale VW Bug but has a big metal fin on the back, earning it the nickname “Land Squid.” I called Martin, described the Land Squid, and he said, “I own one.”

FYI also underwrote my Kyrgyzstan horseback ride where I discovered the six-wheel-drive Soviet Zil truck.

My obnoxious defense of SUV obnoxiousness was written for the London Sunday Times, and given the number of times the MG I owned in college broke down, the Brits had it coming.

And my proposal for a linear National Park went off into the ether of some Webzine called Winding Road that never paid me. The Internet in a nutshell.

I confess to a bit of self-plagiarism in this volume. The chapter about my trip across India was, in part, previously anthologized in The CEO of the Sofa. I’ve re-reprinted it because I wrote two versions, one for Rolling Stone emphasizing culture, politics, and economics in India and one for Automobile emphasizing the Land Rover Discovery II, out the window of which I was seeing the culture, politics, and economics of India. In CEO I mainly used the Rolling Stone article. Here I’ve combined both and written more about the driving. The driving was gruesome. “If it bleeds, it leads,” is always a wise rule in journalism. Another reason for giving India a second chance between book covers was that The CEO of the Sofa—an assortment of light and frivolous sketches from the happy-go-lucky Clinton era—had a publication date of 9/10/01.

I also palmed an item from Republican Party Reptile. It’s an instructional tract called “How to Drive Fast on Drugs While Getting Your Wing-Wang Squeezed and Not Spill Your Drink.” I couldn’t collect my automotive writing and not include this. Plus I’ve wanted an opportunity to respond to my youthful ravings ever since I turned fifty and my drug of choice became blood pressure medicine.

Speaking of age, my friends seem to be getting older. I don’t know what’s the matter with them. A number of the good people mentioned in this book have passed on the double yellow line of lifespan’s highway. Most notably the car world feels the loss of Jim Williams, Humphrey Sutton, Trant Jarman, and Bill Neale. Fortunately they were all careful to live so as to never miss a drink, a romance, or a fast drive. Every pleasure that you forego on Earth is a pleasure you won’t get in heaven.

One of my deceased friends had a brain tumor. He was lucky enough—or perhaps worthy enough—that his tumor seemed to destroy the parts of the brain that generate sadness, anger, irritation, and regret. He went off into unconsciousness with a smile on his face. He was blessed with a loving wife and she took care of him at home even after he became comatose. She used to speak to him as if he could hear, though he showed no sign of response. One day, as she was leaving the house, she reflexively asked her husband, “Is there anything I can get for you?”

He spoke for the first time in months. “Yes,” he said, “a ten-thousand-dollar blow job.”

I thank him for his inspiration. And there is one more thanks I need to give. For nineteen years she’s been with me through thick and thin. She’s vivacious and exciting. She’s a little unpredictable but she has a solid core of common sense. She’s glamorous but not flashy, powerful but not pushy about it. I can rely on her absolutely. And she’s more beautiful than ever, my 1990 Porsche Carrera 2. (And my wife is also fabulous.)

INTRODUCTIONTHE END OF THE AMERICAN CAR

The feminists grabbed our women,

The liberals banned our guns,

The health cops snuffed our cigarettes,

The bailout has our funds,

The laws of Breathalyzing

Put an end to our roadside bars,

Circle the Fords and Chevys, boys,

THEY’RE COMING TO TAKE OUR CARS

It’s time to say . . . how shall we put it? . . . sayonara to the American car. The American automobile industry—GM, Ford, even Chrysler—will live on in some form, a Marley’s ghost dragging its corporate chains at taxpayer expense. The fools in the corner offices of Detroit (and the fool officials of Detroit’s unions) will retire to their vacation homes in Palm Beach (and St. Pete). They no more deserve our sympathy than the malevolent trolls under the Capitol dome. But pity the poor American car when Congress and the White House get through with it—a lightweight vehicle with a small carbon footprint, using alternative energy and renewable resources to operate in a sustainable way. When I was a kid we called it a Schwinn.

Oh well, it’s been a great run these past 110-odd years since the Duryea brothers built the first American car in Spring-field, Massachusetts. If the Duryea Motor Wagon Company had been a success, Springfield, Massachusetts, might be today’s Motor City, full of abandoned houses, unemployment, drug dealing, violent crime, and racial tensions, which Springfield, Massachusetts, is full of anyway. But we owe the American car a lot more than just the entertaining spectacle of Detroit’s felon mayor Kwame Kilpatrick. In fact many people my age owe their very existence to the car, or to the car’s backseat, where—if our birth date and our parents’ wedding anniversary are a bit too close for comfort—we were probably conceived.

There was no premarital sex in America before the invention of the internal combustion engine. You couldn’t sneak a girl into the rec room of your house because your mom and dad were unable to commute so they were home all day working on the farm. And your farmhouse didn’t have a rec room because recreation had not been discovered due to all the farmwork. You could take a girl out in a buggy, but it was hard to get her in the mood to let you bust into her corset because the two of you were seated facing a horse rectum. It spoils the atmosphere.

Cars let us out of the barn and, while they were at it, destroyed the American nuclear family. As anyone who has had an American nuclear family can tell you, this was a relief to all concerned. Cars also caused America to be paved. There are much worse things you can do to a country than pave it, as the Sudanese are proving in Darfur. (And do we car nuts ever hear a word of thanks for this largesse from the scatter-skulled, face-skinned, limbs-in-casts skateboarders?)

Cars fulfilled the ideal of America’s founding fathers. Of all the truths we hold self-evident, of all the unalienable rights with which we’re endowed, what’s most important to the American dream? It’s right there, front and center, in the Declaration of Independence: freedom to leave! Founding fathers, can I have the keys?

The car provided Americans with an enviable standard of living. You could not get a steady job with high wages and health and retirement benefits working on the General Livestock Corporation assembly line putting udders on cows.

The American car was a source of intellectual stimulation. Think of the innovation, the invention, the sheer genius that transformed the 1908 Model T Ford into the 1968 Shelby Cobra GT500 in the course of a single human lifetime full of speeding tickets. Compare this to progress in the previously fashionable mode of human transportation. Equine design and production have remained much the same for three thousand years. And when it came to creativity nobody thought to put a stirrup on a saddle until about 500 AD. If the engineering development of the automobile had proceeded at that pace we’d be powering ourselves down the road by running with our feet stuck through a hole in the floor like Fred Flintstone. (Although it may come to that in the 2010 Obamamobile.)

And upon the fine arts the American car has had a welcome effect. The minute the house lights dim for a symphony, opera, or play, we can run out, start the car, and effect a welcome escape.

The saga of the American car is no abstract matter to me, no subject of fanciful theories. Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid may think they were transported home from the maternity ward on pink, fluffy clouds supported by cherubs but I know that the car got me to where I am.

My grandfather Jacob Joseph (“J.J.”) O’Rourke was born in 1877 on a patch of a farm outside Lime City, Ohio. He was one of ten kids. They grew up in a one-room unpainted shack. I have a photograph of them, lined up by age, staring at the photographer, amazed to see someone in shoes. My great-grandfather Barney was a woodcutter and a drunk and an illiterate. I have a copy of the marriage certificate with his X. Barney’s only accomplishment—aside from the ten prizes he won on the corn-shuck stuffing of the poor man’s roulette wheel—was to train a pair of draft horses to haul him home dead drunk, flat on his back, in his unsprung “Democrat wagon.” He died a pauper in a charity hospital run by the Little Sisters of the Poor.

Grandpa Jake left home armed with a fifth-grade education, heading for the bright lights of Toledo. It’s a short drive, as I remember from Grandpa taking me to see Lime City. But it’s a damn long walk. Grandpa went to work as a mechanic for a buggy maker. When horseless buggies came along he fixed them too. For the rest of his life he called cars “buggies.” It didn’t take him long to realize that cleaner hands were to be had and more money was to be made selling the things instead of repairing them. (And my uncle Arch’s birth date and my grandparents’ wedding anniversary were a bit too close for comfort.)

The upshot—by the time I arrived in the 1940s—was O’Rourke Buick. Grandpa and Uncle Arch owned the dealership. My father was the sales manager. Dad’s younger brother, Joe, ran the used car lot. Baby brother Jack was a salesman. Cousin Ide was in charge of the parts department. Various aunts and girl cousins worked in the office. The boy cousins and I got our first jobs cleaning and waxing cars. (Shorty, the old black man in charge, told me, “Always leave some lint in the corners of the windows, that way they know you washed ’em.”)

Arch’s son-in-law, my cousin Hep, would go on to run the Ohio Car Dealers Association and I would go on to do what I’m doing here. Which has something to do with cars, but there are times I wished I’d stayed in Toledo and starred in late-night local TV commercials: “Arrrgh, mateys, sail on down to Pirate Pat’s Treasure Island Buick, where prices walk the plank! And don’t miss our Pieces of V-8 used car lot! Free chocolate doubloons for the kiddies!”

Grandpa died in 1960, full of years and honors (albeit honors from Rotary, Kiwanis, and Lions clubs, Elk and Moose lodges, and the Shriners, as befits a good car dealer). My family owes everything to the American car. What with the inability to read and write and no food and all, O’Rourke family history does not begin until the beginnings of the American car. Now some O’Rourkes have even gone to college.

I take the demise of the American car personally. I’m looking around furiously for someone or something to blame. Ralph Nader for instance. What fun it would be to jump on him with both feet and send the pink Marxist goo squirting out of his cracked egghead. And let’s definitely do that even though Ralph is seventy-five and insane. But it took more than one man and his ignorant and ill-written book Unsafe at Any Speed to wreck the most important industry in the nation. (My high school girlfriend Connie had a Corvair. Connie was the worst driver in the world—and one of the fastest. If Connie couldn’t get that rear-engine, swing-axle setup to spin out and flip, nobody could.)

Pundits say there’s plenty of blame to be shared for the extinction of the American car. But I’m not so sure about that either. True, car executives are knuckleheads. But all executives are knuckleheads. Look at Bill Gates. If you were worth eleventy bazillion wouldn’t you give up on your That Seventies Show optometrist look and go to a barber college and get a decent $5 haircut? Labor union leadership is maddening. But it’s one thing to be mad at union leaders and another thing to expect them to stand on a chair at the UAW hall and shout, “We demand less money from the bosses!”

Car company workers are making $600 an hour plus overtime—or so it’s claimed. In the first place, these people get laid off every time a camel farts at an OPEC meeting. Maybe their pay is too high, but it’s not like they’re getting that pay. And their jobs are harder than being president. All Barak Obama has to do is look cool. If a couple hundred armed Secret Service agents had my back and were also ready to run down to the corner store and get me a pack of smokes, I’d look cool too. (And when you’re president you can’t get laid off. We know, because we tried with Clinton.)

American car designers and engineers are supposedly at fault because American cars fell behind foreign cars in sophistication of design and engineering. American cars fell especially behind during the 1960s era of chrome and tail-fin excess that car-hating Volvo-butts still like to natter on about. Too much jogging has addled their brains. There’s little chrome and barely a fin to be seen on American cars after 1960, excepting the modest lark tails on Cadillac rear fenders and the shark attack of the 1961 Chryslers. In fact, early ’60s American cars exhibit some of the cleanest, crispest, most restrained lines in automotive design history—the 1962 Lincoln Continental; the Avanti; the last of the Studebaker Hawks; the 1964 Buick Electra, Oldsmobile 98, and Pontiac Grand Prix hardtops; the 1965 Buick Riviera; those maligned Corvairs, including the Corvair Greenbriar precursor to the minivan; Mustangs; the 1965 Pontiac GTO and similar early muscle cars; and the 1964 Rambler American sedan in its own oddball way. Then, when it comes to down-and-dirty, gnarly, totally unrestrained lines, there’s the Corvette Stingray.

As for engineering you’ll note that Carroll Shelby did not create the Shelby Cobra by taking a 1961 AC Ace and sticking an AC Ace engine in it. America made the best engines in the world—compact, powerful, gas-station-mechanic-proof V-8s that were overbored, understressed, and delivered terrifying horsepower at comforting rpms. American engines were cheap to make, simple to fix, and easy to hot-rod. Europe was producing more complicated and—to be fair—more efficient engines. But Europe had to. European cars were taxed by engine size as though performance were a disease of the liver. European gasoline cost more per liter than Château Lafite 1961. And European racing formulas stipulated a volume of displacement that wouldn’t get an American eighth grader drunk if it were filled with bourbon.

European chassis and running gear were more complicated as well—birdcages, monocoques, unibodies, four-wheel independent suspensions, five-speed synchromeshes, rack-and-pinion steering, and disc brakes that squealed like a girl. Wonderful stuff—light, nimble, and damned near useless in America. Useless, that is, when it wasn’t broken. American roads, American weather, and Americans took that fancy European engineering and smashed it to bits as if it were a dainty Dresden china teacup.

Among people who have no idea what they’re talking about there is an idea that nifty, thrifty, and brilliant automobiles were being manufactured first in Europe and then in Japan. Meanwhile America was turning out clunking, profligate, and stupid lead sleds. That’s crap. And so were—and are—most of the cars made in Europe and Japan.

By the end of the 1950s American cars were so reliable that their reliability went without saying even in car ads. Thousands of them bear testimony to this today, still running on the roads of Cuba though fueled with nationalized Venezuelan gasoline and maintained with spit and haywire. This was a big change from just a few years before (as readers of a following chapter on a trip across the United States in a 1956 Buick will note).

American cars were sophisticated when sophistication was called for. Foreigners have yet to figure out how to make decent power steering or a worthwhile automatic transmission. But American carmakers have always favored solidity, plain mechanicals, and sturdy overbuilding. (And, P.S., that 1964 Electra hardtop could be had new for four grand.)

There’s nothing special about a leaf-spring-mounted solid rear axle. However, it’s the thing to have if you decide to use your Fairlane 500 to pull a wheat combine. Americans have been known to do that. Disc brakes are better than drum brakes, but drum brakes are less expensive to make and assemble. Drum brakes fade but they do work the first time you use them. As the great American car journalist Brock Yates has pointed out, car journalists tend to forget that the point of brakes in an emergency stop is to stop you once. If you have to make emergency stop after emergency stop, you have a problem worse than your brakes.

American carmakers made—and, after dozing at the wheel in the ’70s and ’80s, still make—cars well suited to their country and their customers (and particularly well suited to the size of both).

Foreign carmakers, on the other hand, were making my 1960 MGA with foot wells constructed of wooden boards that rotted, leaving me running with my feet stuck through a hole in the floor like Fred Flintstone. At an SCCA time trial, one of the MG’s ridiculous, untuneable SU side-draft carburetors sprayed gasoline all over my red-hot exhaust headers causing a very rapid clearing of the pit area. Also, as I was pulling out of the driveway one day, the MG’s radio caught fire. “Home by Dark” was the motto of the Lucas Electrical Company, which also made the parts on a friend of mine’s Riley roadster. The Riley’s battery exploded when we tried to give the car a jump-start because some idiot Englishman had specified positive grounding.

Noted car photographer Humphrey Sutton drove a Mini (an original 1960s Austin one) over a protruding New York City manhole cover and tore the oil pan and crankcase out of the car. Another time, in Scotland, Humphrey got a Fiat 600 so firmly jammed in reverse gear that it had to be driven (Humphrey swore this was true) backward from Glasgow to Edinburgh.

Car and Driver editor David E. Davis and Brock Yates drove a 1964 Rover 2000TC from Chicago to New York and were so impressed they called it “the best sedan we have ever tested,” resulting in loud vender complaints and a major falloff in subscription renewals. “We made that claim,” said David E., “before we discovered the screw under the Rover's hood that, if given a quarter-turn counterclockwise, caused everything to fall off the car.”

In college, after my MG imploded, I had a 1960 Mercedes 190 sedan that blew a head gasket because it had had its head gasket replaced. The mechanic hadn’t tightened the head bolts correctly. I mean, he’d tightened them with the correct amount of torque but he hadn’t tightened them in the correct order. By way of contrast, the next car I had was a 1959 Plymouth Belvedere with Chrysler Corporation’s ancient L-head 6. There was a leak in the radiator hose. I didn’t notice because the bong was blocking my view of the temperature gauge. Anyway, I ran every ounce of coolant out of the cooling system and the engine seized. I duct-taped the radiator hose and filled the radiator with a bystander’s garden house. The Plymouth started on the first try and ran for years.

I could go on. And I will if you get me started on the rice-burner junk prior to Datsun’s 510 and 240Z. Early generations of Japanese cars were styled by the Hello Kitty factory and had model designations such as “Sapsucker,” “Blowfly,” and “Hello Kitty.” Early generations of Japanese motorcycles weren’t much better. My 250cc Suzuki X6 Hustler (there’s a name) fried a spark plug every hour. The only way the plug could be changed was by using a 15/16ths box-end wrench with a dip. This awkward bugger of a tool had to be carried bungee-corded to the rear fender of the X6 along with a box of spare Champions. As for other highlights of Japanese engineering, remember the Honda Dream with square shock absorbers?

No, the American car industry was not destroyed by its cars. The American car industry was destroyed by the Fun-Suckers. You know the Fun-Suckers. You may be married to one. The Fun-Suckers go around saying how unsafe this fun thing is and how unhealthy that fun thing is and how unfair, unjust, uncaring, insensitive, divisive, contagious, and fattening every other thing that’s fun is.

The Fun-Suckers are a bit too careful, a bit too concerned, a bit too scrupulous. That’s bullshit. They’re evil and they hate us. The motive behind spoiling things for others and then throwing a wet blanket over the rained-on parade is a matter of neither caution nor morals. The Fun-Suckers suck the fun out of life in order to gain control. They’ve found a way to achieve power without merit. Nothing requires less information, education, or accomplishment than saying that everything’s wrong. It’s wrong to risk lives, wrong to use up earth’s resources, wrong to pollute air, wrong to support an economic system that heightens income inequalities, wrong to own a big, expensive car, drive it fast, and vote Republican.

The Fun-Suckers have been around forever. But they didn’t used to have the influence they have now. The ruling class of yore was too fond of its dangerous fun. The nobility was having a ball (and PETA be damned) chasing game animals through the serfs’ standing corn and chasing serfs as well if any buxom serf lasses were spied. Dukes and princes spent their days warring with infidels and each other and their nights feasting themselves into oblivion. The Fun-Suckers had to rely on religious zealotry to make others miserable and themselves important. Fun-Suckers were reduced to burning a few books and witches, pestering Copernicus and Galileo, and making everyone eat carp pie on Fridays. (Although, to judge by the cumbersome impracticality of medieval armor, knights and squires may have had to deal with a Ralphius Naderum.)

Even the threat of damnation failed the Fun-Suckers when the Enlightenment dawned, and elite thinkers like Voltaire gave up the idea of hell for the idea of a hell of a good time. And yet Fun-Sucking was not to be thwarted. The invention of democracy gave the Fun-Suckers a party platform. What better way to gain power without merit than by being the kind of pea-brained, unaccomplished Fun-Sucker who runs for political office? And what makes a better stump speech than saying that everything’s wrong? Elect the Fun-Sucker.

Cars were a perfect opportunity for Fun-Sucking. Ruining cars could produce an even bigger sensation (and government) than the Fun-Suckers’ previous golden oldie, Prohibition. After all, at any given moment there are a few people on the wagon and hence not affected by Prohibition. But Americans never get out of their cars.

Cars were everyplace. We couldn’t do without them. The car business was too big, complicated, and socially prominent to go on the lam. Cars were a way for the Fun-Suckers to clamp their lamprey jaws onto everybody’s seat upholstery.

The Fun-Suckers started small, with seat belts to make sure we’d be trapped inside flaming car wrecks and padded dashboards so we wouldn’t injure our knuckles while pounding the dash in frustration as we burned to death. Then the Middle East’s predatory goat molesters gave Fun-Suckers the excuse they were looking for, with the 1973 oil embargo.

The Fun-Suckers were able to turn the automobile into a public enemy, an outlaw they could persecute without compunction. Cars were shackled with five-mph bumpers that spoiled the styling of everything from 3.OCS BMWs to landau-style vinyl-roofed opera-windowed Gauche DeVilles. The idea was to make us fun-lovers look ridiculous, to turn us into objects of popular ridicule and scorn. The Fun-Suckers are doing the same thing to our kids by making them wear bike helmets, knee and elbow pads, shin guards, safety goggles, and steel-toed boots to use the teeter-totter at the playground, after which they have to wipe themselves all over with Purell hand disinfectant.

Our children tamely submit to this because they were torn from our fun-filled arms as babies and strapped, belted, buckled, and bound into lonely, isolated rear-facing infant carriers where they grew up without normal social contact or human interaction, causing them to become the passive teen video-gaming thumb-twiddlers and pasty Facebookers who are tweeting, texting, iPhoning, and Wii-wiggling like Internet-wits while they sprawl in front of the high-def TV in our homes. These pallid adolescents are easy prey to the brandishers of Nerf hope and the loose change makers who are sucking fun in the Obama administration.

The fifty-five-mile-per-hour speed limit had a similar intent. The dreary and tedious rate of travel was meant to produce “highway hypnosis” in the American electorate so that the Carter White House’s pointy-headed grand wizards of the Fun Sux Klan could employ posthypnotic suggestion to make people do their bidding. Americans would be rendered so zombielike and devoid of free will that, heedless of all pangs of conscience or instincts for self-preservation, they’d reelect Jimmy Carter. Fortunately, Jimmy’s brother Billy had too many beers, told all, and the plot was foiled.

CAFE standards were imposed to make American cars use less gas and thereby keep the oil crisis going longer. If American cars used less gas the world wouldn’t run out of oil. And as long as the world didn’t run out of oil the sheep-humped sheikhs of the Mideast’s giant kitty-litter tray—the Fun-Suckers’ most important allies—would remain rich, powerful, and happily mutton-buggered.

Pollution controls were installed on automobiles to increase the amount of pollution. You’ll recall that, at first, air pollution from cars was nothing but a wisp of smog in the sky, easily remedied with a tune-up and positive crankcase ventilation. Then the atmosphere filled with lead that damaged our brains, followed by carbon monoxide that poisoned our bodies. Now hydrocarbons cook the planet and melt the ice caps and cause us all to die of heat prostration and drowning. That’s no fun. Truly the Fun-Suckers are wicked, wicked people.

Next came the DUI hysteria with legal blood-alcohol levels lowered to the point where you can’t drive a car all Sunday if you received communion at 8 A.M. Mass. This was the Fun-Suckers’ most obvious attempt to create a police state since it takes one full-time police officer for each adult male in America to enforce current DUI laws.

Drinking and driving is not a problem and never has been. Bravery and driving is the problem. And beer makes young men brave. The answer isn’t more cops. The answer is more drugs. Give those young men some peyote and mescaline and LSD with their beer and watch their bravery vanish. Mile markers jump out from the berm, hopping on their single legs and forming into packs. Their rectangular, numbered heads flash with green reflective menace. The centerline rises from the pavement. The giant yellow-striped serpent coils to strike. Meanwhile, a highway overpass gapes—the jaws of hell. Abandon all joyriding ye who enter here. Those young men will be crawling down I-40 at fifteen miles an hour the way I was forty years ago.

And then there is the air bag. It kills short people when it deploys. It kills short people, but what it does to short people who are smoking big cigars is too horrible to contemplate. I’m about the height of New York’s Mayor Bloomberg. I do love my double-corona Havanas with a ring guage equal to my number of years on the planet. I don’t think I have to spell out who is #1 on the Fun-Suckers’ hit list.