Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

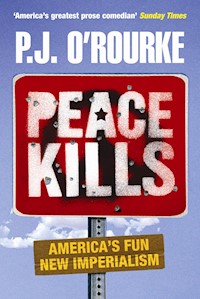

'A hilarious, no-holds-barred tour of the new world order, from 'America's greatest prose comedian' - Sunday Times Peace Kills is an eye-opening look at a world much changed since O'Rourke wrote his bestselling Give War a Chance in which he declared the most troubling aspect of war is sometimes peace itself. In this latest collection of adventures, P. J. O'Rourke casts his mordant eye on America's recent forays into warfare. Imperialism has never been more fun. O'Rourke first travels to Kosovo, where he meets KLA veterans, Albanian refugees and peacekeepers, and confronts the paradox of 'the war that war-haters love to love'. He visits Egypt, Israel and Kuwait, where he witnesses citizens enjoying their newfound freedoms - namely, to shop, to eat and to sit around a lot. Following 11 September, O'Rourke examines the far-reaching changes in the US, from the absurd hassles of airport security; to the dangers of anthrax. In Iraq, he witnesses both the beginning and the end of Operation Iraqi Freedom and takes a tour of a presidential palace, concluding that the war was justified for at least one reason: criminal interior decorating.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 269

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PEACE KILLS

ALSO BY P. J. O'ROURKE

Modern Manners

The Bachelor Home Companion

Republican Party Reptile

Holidays in Hell

Parliament of Whores

Give War a Chance

All the Trouble in the World

Age and Guile Beat Youth, Innocence, and a Bad Haircut

Eat the Rich

The CEO of the Sofa

PEACE KILLS

P. J . O'ROURKE

ATLANTIC BOOKS

LONDON

First published in the United States of America in hardback by Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in hardback in 2004 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Copyright © P. J. O'Rourke 2004

The moral right of P. J. O'Rourke to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

‘Homage to a Dream from Collected Poems by Philip Larkin, edited by Anthony Thwaite.

Copyright © 1988, 1989 by the Estate of Philip Larkin.

Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC, in the United States, and by Faber and Faber Limited in Canada and the United Kingdom.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 1 84354 272 2 (hardback)

1 84354 361 3 (trade paperback)

Printed in Great Britain by { }

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

In Memory of Michael Kelly

He could have advocated the war in Iraq without going to cover it. He could have covered it without putting himself in harm's way. But liberty is an expensive feast. And Mike was a man who always picked up the check.

CONTENTS

1 WHY AMERICANS HATE FOREIGN POLICY 1

2 KOSOVO November 1999 17

3 ISRAEL April 2001 31

4 9/11 DIARY 57

5 EGYPT December 2001 81

6 NOBEL SENTIMENTS 115

7 WASHINGTON, D.C., DEMONSTRATIONS April 2002 123

8 THOUGHTS ON THE EVE OF WAR 139

9 KUWAIT AND IRAQ March and April 2003 143

10 POSTSCRIPT: IWO JIMA AND THE END OF MODERN WARFARE July 2003 187

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I like the places I write about. I enjoy the people. I've had a good time wherever I've gone, Iraq included. My subject, in a way, is pleasure. This is really a book about pleasantness, which is why I dedicate it to Mike Kelly. He and I were drinking one night—a pleasurable occasion—and I remember him saying, "Wouldn't it be pleasant if we could do something with the forces of evil other than hunt them down and kill them?" If we increased funding and reduced class sizes at the fundamentalist madras schools … If all the Mrs. bin Ladens had access to day care and prenatal health services … If, when Germanic hordes were threatening Rome, a Security Council meeting of the United Despotisms had been called, and Marcus Aurelius had pursued a multilateral foreign policy working in cooperation with the Parthians, the Huns, and the Han Chinese … If Aztec priests had taken it on faith that their captives had a lot of heart … If Australopithecus and the saber-toothed tiger had engaged in meaningful dialogue …

How pleasing would the whole world be,If everyone would just say please.

And thank you, too, of course, thanks being what this part of a book is about. I thank Mike Kelly—a little late, as heartfelt thanks tend to be. But I assume that Mike is keeping current in Reporters' Heaven (open bar and porthole in the floor through which highly placed sources quoted on the condition of anonymity can be watched as they fry). A few years back Mike took over as editor of The Atlantic. I was writing for Rolling Stone, where my job was to be the Republican. After sixteen years even Rolling Stone had figured out that this made as much sense as offering readers a free bris. Also my excellent and long-suffering editor there, Bob Love, was about to head to someplace where "Marcus Aurelius" would not be mistaken for Beyoncé's latest brand of bling. Mike called and said, "I can pay you less."

Most of this book originally appeared, in somewhat different form, in The Atlantic, first under the brilliant editorship of Mike Kelly, then under the brilliant editorship of Cullen Murphy. If you think the book good, behold what three short Irishmen can accomplish when they've lost the key to the liquor cabinet. If you think the book otherwise, assume that, after a certain amount of feeling around in the carpet, they found it.

The first chapter contains material from a piece that appeared in The Wall Street Journal, on the op-ed page edited by Max Boot—may he long give enemies of America a taste of his name.

I'm not sure that Bob Love would care to do that to Robert Bork. But it was under Love's stewardship of Rolling Stone that "Kosovo—November 1999" appeared with its Borkian pessimism, doubtless causing a puzzled tug of a lip ring and a quick flip of the page by more than one reader.

As important as getting "Kosovo" into print was getting there in the first place. Irena Ivanova and Biljana Bosiljanova of the Macedonian Press Center made all the arrangements. Nothing has ever been simple or easy in the Balkans except for my stay there, thanks to Irena and Biljana.

My old friend Dave Garcia came from Hong Kong to travel with me through both Israel and Egypt, just for the hell of it. (Luckily, no literal experience of the cliché was had.) Dave has a knack for finding tequila in the least likely places. Besides being good company, he is universally simpatico. The most foreign foreigners take to Dave immediately. He understands their point of view. It is Dave's opinion that everybody's point of view can be understood if you stipulate that everybody is crazy. When it comes to intelligent treatment of foreigners, Dave is the next best thing to Thorazine.

Not that it was always the foreigners who needed the psychiatric aid. Talking to Ashraf Kalil was therapeutic in helping me cope with that maddening city Cairo. Michele Lieber was a link to sanity on 9/11/01, as was the Palm restaurant in Washington, D.C., where I've been taking medication for years under the supervision of Tommy Jacomo, Jocelyn Zarr, and Kevin Rudowski. And, during the initial weeks of the Iraq war, I would have gone nuts from boredom if I hadn't had excellent companions with whom to crawl the walls of Kuwait. Chief among these were Matt Labash and Steve Hayes of The Weekly Standard and the "room boy" at their hotel. The last shall go unnamed, but if any reader is offered the chance to direct a remake of Thunder Road set in Kuwait, please cast that young fellow in the Robert Mitchum moonshine-running hero role.

Alas, most of the time in Kuwait was passed sober, and there wasn't much to do but pass the time. Long conversations with pals when neither you nor they have had a drink can be a test of palship. I fear I received an "Incomplete." Others passed with honors: Alex Travelli of ABC, Simon McCoy and Philip Chadwick of Sky News, Cohn Baker of ITN, Ernie Alexander, Marco Sotos, Spanish documentary filmmaker Esteban Uyarra, and my friends Charlie Glass and Sal Aridi, whom I met at my virgin war, in Lebanon, twenty years ago.

ABC News, as it has many times before, allowed me into its Big Top and let me tag along with the parade of real journalists. I suppose they hope that one day I'll grab a shovel and clean up behind the elephants. In lieu of that, they gave me a part-time job as the world's worst radio reporter. ("This is P. J. O'Rourke in Kuwait City and not a darn thing is happening.") My boss in Kuwait, Vic Ratner—a real radio reporter with the old-school voice and the AK-47 delivery—was more than welcoming and patient. Thank you, Vic, and thank you, Chris Isham, Burt Rudman, Peter Jennings, John Meyerson, Deirdre Michalopoulos, Wayne Fisk, John Quinones, and all the cameramen, soundmen, and technicians in whose way I constantly was. Here's to you, ABC News—don't let them make you wear those mouse ears on camera.

Thanks also to Alex Vogel, who did his best to repair a faltering ABC Land Rover in Iraq by phone from New Hampshire. Looting was rife in Iraq at the time and Alex asked— amid discussion of diesel compression loss due to piston scoring from desert grit—"If New York is ever freed from oppression by liberals, will there be looting in Manhattan?" I believe, Alex, that Manhattanites have been doing that all along, on Wall Street. But there will be plenty of sniping from The New York Review of Books.

Max Blumenfeld, from the Department of Defense, managed to get me to Baghdad, where Major William Dean Thurmond made me at home. Dean, you are an officer, a gentleman, and damn handy at making coffee in plastic sacks using the chemical heater packs from the Meals Ready to Eat. Additional thanks to Major Mike Birmingham, of the Third Infantry Division, and a tip o' the pants to Derek and Ski (they'll know what I mean).

At the Baghdad airport I was billeted with good friends of mine, the courageous and beautiful Alisha Ryu from Voice of America and the equally courageous if not quite so good-looking Steve Kamarow of USA Today. With us was The Philadelphia Inquirer's Andrea Gerlin, fresh from combat coverage with a brilliant idea for selling American women a fitness and weight-loss program based on sleeping in holes, getting shot at, and eating MREs. James Kitfield from The Atlantic's sister publication, The National Journal, was there as well. Kitfield is fluent in the language of the military, which is harder to translate than Arabic. Were it not for James, I would still be pondering what it means to be in a part of town that was "controlled but not secured" and thus I would be blown to bits.

We had, as I mentioned, a good time in Baghdad. Chaos is interesting. Reporters would rather be interested than comfortable. Put that way, it sounds noble enough. Put another way, we would rather be interested than well paid, worthwhile, responsible, or smart.

Fifty-nine years ago Iwo Jima might have been a little too interesting for this reporter. At least it's still uncomfortable. It was the idea of Tim Baney to take me to Iwo. Please use Baney Media Incorporated for all your television programming needs. (Except Tim doesn't do weddings, although for a price …) We traveled with ace cameraman Pat Anderson— three Irishmen again, but this time only one of us was short. Transport from Okinawa was arranged through the kind offices of Kim Newberry and Captain Chris Perrine, USMC. On the island battlefield we were entertained (if that verb ever can be used in connection with war) and instructed (a verb not used in connection with war often enough) by Sergeant Major Mike McClure, USMC, and Sergeant Major Suwa, Japanese Self-Defense Forces.

There are many other people to whom I owe thanks. My thanks credit is woefully overextended. I am in gratitude Chapter 11. Any number of debts of obligation doubtless will go unpaid as I attempt to settle my accounts. For years Max Pappas was my invaluable research assistant. I know he misses sitting in the kitchen trying to extract Dora the Explorer from the disk drive while dog and children gnaw on his pants cuffs. And I'm sure he's much less happy and fulfilled in his present position as policy analyst at Citizens for a Sound Economy, no matter what he says to the contrary.

Likewise, sisters Caitlin and Megan Rhodes escaped the same kitchen computer post to, respectively, go to college and pursue a career in Chicago. They are probably, this minute, sprinkling dog hair and Froot Loops onto their laptop keyboards for nostalgia's sake.

Dr. William Hughes has kept me healthy through years of Third World travel. He carefully researches the hideous diseases that rage in the places I'm about to visit, gives me a bottle of pills, and says, "Take these if you begin to bleed from the ears and maybe you'll live to be medevaced."

For all questions on military matters, I go to Lieutenant Colonel Mike Schellhammer, who introduced me to my wife and who, therefore, she tells me, cannot be wrong about anything. If there are errors about military-type things in the following pages, it's because Mike, an intelligence officer, is very tight-lipped. "I could tell you what I do," Mike says, "but I'd have to bore you to death."

Don Epstein and his colleagues at Greater Talent Network continue to find lectures for me to give and lecture audiences who do not throw things that are large or rotten.

My literary agent, Bob Dattila, maintains his remarkable ability to extract money from people in return for work that accidentally got erased in the hard drive; was lost by UPS; just needs a slight final polish; was e-mailed yesterday, honest, but the attachment probably couldn't be opened because of that computer virus that's going around; and is really, truly, completely finished in my head—and I just need to write it down.

The Atlantic is the only magazine in America with a readership and staff who are sitting, clothed, and in their right minds. Writing for The Atlantic is an honor I don't deserve, and you'd think Cullen Murphy would be able to tell that from my spelling, grammar, and punctuation. But when I read what I've written in The Atlantic, I find that it's, mirabile dictu, in good English. (Or, if the occasion warrants, as it does with mirabile dictu, it's in good Latin. The phrase is Virgil's—as if I'd know.) This is the work of The Atlantic's deputy managing editors Toby Lester and Martha Spaulding, of senior editor Yvonne Rolhausen, and of staff editors Elizabeth Shelburne, Joshua Friedman, and Jessica Murphy. Bless you all, and you, David Bradley, for buying The Atlantic and saving it from a dusty fate in library stacks next to bundles of Transition, New Directions, and The Dial, or a fate worse than dusty, running features such as "The Most Important One or Two Books I've Ever Read" by Charlize Theron.

Historically, Grove/Atlantic, Inc., branched from The Atlantic Monthly, although a cutting was made and transplanted into the rich mud of the New York literary scene, which, combined with a graft to the sturdy root of Grove Press, caused this metaphor to badly need pruning. Grove/Atlantic is a great publishing house, and I would say that even if it hadn't published all my books. Grove/Atlantic chief, Morgan Entrekin, is a true aristocrat among publishers, and I would say that even if I didn't owe him money. Go buy a lot of Grove/Atlantic books, no matter what the subject, and maybe Morgan will let me off the hook for that advance on my proposed Howard Dean presidential biography. You'll be doing a favor not just to me but to every person at Grove/Atlantic. They are all true aristocrats of publishing, albeit impoverished aristocrats due to—let's be blunt—you, negligent reader, spending your money on DVDs and video games. A prostration, a curtsy, a bow, and a yank on the forelock to Charles Rue Woods, archduke of art design; Judy Hottensen, maharani of marketing; Scott Manning, prince regent of public relations; Debra Wenger, caliph of copyediting; and Michael Hornburg and Muriel Jorgensen, potentates of production. Even if this book gets remaindered, it will be a royal flush.

There is one more performer of thankless tasks to thank. Tina O'Rourke provides sage editorial advice, pays the bills, keeps the books, raises the children, runs the household … But there are not trees enough to make the paper to give me the space to list all the things my wife does. I will be ecologically conscious and eschew sprawl by listing, rather, the things Tina does not do. She doesn't stare disconsolately at a blank page all day and come home reeking of cigar smoke and snarl at the kids and drink gin. And for these, and many other things, we love you, dear.

Let me close by acknowledging the inspiration I received from that now nearly forgotten deep thinker about foreign policy issues, General Wesley Clark. Addressing an audience in Keene, New Hampshire, during the 2004 presidential primary campaign, General Clark said, "I came into the Army because I believe in public service, not because I want to kill people." How surprised Saddam Hussein would have been to see General Clark in public, coming across the Kuwait border with a napkin over his arm, carrying a tray of bratwurst and beer.

Next year we are to bring the soldiers home For lack of money, and it is all right. Places they guarded, or kept orderly, Must guard themselves, and keep themselves orderly. We want the money for ourselves at home Instead of working. And this is all right.

It's hard to say who wanted it to happen, But now it's been decided nobody minds. The places are a long way off, not here, Which is all right, and from what we hear The soldiers there only made trouble happen. Next year we shall be easier in our minds.

Next year we shall be living in a country That brought its soldiers home for lack of money. The statues will be standing in the same Tree-muffled squares, and look nearly the same. Our children will not know it's a different country. All we can hope to leave them now is money.

—Philip Larkin "Homage to a Government" England, 1969

1WHY AMERICANS HATE FOREIGN POLICY

I was in Berlin in November 1989, the weekend the wall opened. The Cold War was over. The ICBMs weren't going to fly. The world wouldn't melt in a fusion fireball or freeze in a nuclear winter. Everybody was happy and relieved. And me, too, although I'm not one of those children of the 1950s who was traumatized by the A-bomb. Getting under a school desk during duck-and-cover was more interesting and less scary than the part of the multiplication table that came after "times seven." Still, the notion that, at any time, the U.S.S.R. and the U.S.A. might blow up the whole world— my neighborhood included—was in the back of my mind. A little mushroom-shaped cloud marred the sunny horizon of my future as an internationally renowned high school JV football player. If On the Beach was for real, I'd never get tall enough to date Ava Gardner. What's more, whenever I was apprehended in youthful hijinks, Mutually Assured Destruction failed to happen before Dad got home from work. Then, in the fall of 1962, when I was fifteen, Armageddon really did seem to arrive. I made an earnest plea to my blond, freckled biology-class lab partner (for whom, worshipfully, I had undertaken all frog dissection duties). "The Cuban missile crisis," I said, "means we probably won't live long. Let's do it before we die." She demurred. All in all the Cold War was a bad thing.

Twenty-seven years later, wandering through previously sinister Checkpoint Charlie with beer in hand, I felt like a weight had been lifted from my shoulders. I remember thinking just those words: "I feel like a weight has been lifted …" A wiser person would have been thinking, "I feel like I took a big dump."

Nastiness was already reaccumulating. I reported on some of it in ex-Soviet Georgia, ex-Yugoslav Yugoslavia, the West Bank, Somalia, and Iraq-ravaged Kuwait. The relatively simple, if costive, process of digesting the Communist bloc was complete. America needed to reconstitute its foreign policy with—so to speak—a proper balance of fruit and fiber. The serious people who ponder these things seriously said the new American foreign policy must include:

• Nation-building;

• A different approach to national security;

• Universal tenets of democracy.

This didn't occur to me. Frankly, nothing concerning foreign policy had ever occurred to me. I'd been writing about foreign countries and foreign affairs and foreigners for years. But you can own dogs all your life and not have "dog policy." You have rules, yes—Get off the couch!—and training, sure. We want the dumb creatures to be well behaved and friendly. So we feed foreigners, take care of them, give them treats, and, when absolutely necessary, whack them with a rolled-up newspaper. That was as far as my foreign policy thinking went until the middle 1990s, when I realized America's foreign policy thinking hadn't gone that far.

In the fall of 1996, I traveled to Bosnia to visit a friend whom I'll call Major Tom. Major Tom was in Banja Luka serving with the NATO-led international peacekeeping force, IFOR. From 1992 to 1995 Bosnian Serbs had fought Bosnian Croats and Bosnian Muslims in an attempt to split Bosnia into two hostile territories. In 1995 the U.S.-brokered Dayton Agreement ended the war by splitting Bosnia into two hostile territories. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina was run by Croats and Muslims. The Republika Srpska was run by Serbs. IFOR's job was to "implement and monitor the Dayton Agreement." Major Tom's job was to sit in an office where Croat and Muslim residents of Republika Srpska went to report Dayton Agreement violations.

"They come to me," said Major Tom, "and they say, ‘The Serbs stole my car.' And I say, ‘I'm writing that in my report.' They say, ‘The Serbs burned my house.' And I say, ‘I'm writing that in my report.' They say, ‘The Serbs raped my daughter.' And I say, ‘I'm writing that in my report.'"

"Then what happens?" I said.

"I put my report in a file cabinet."

Major Tom had fought in the Gulf War. He'd been deployed to Haiti during the American reinstatement of President Aristide (which preceded the recent American unreinstatement). He was on his second tour of duty in Bosnia and would go on to fight in the Iraq war. That night we got drunk.

"Please, no nation building," said Major Tom. "We're the Army. We kill people and break things. They didn't teach nation building in infantry school."

Or in journalism school, either. The night before I left to cover the Iraq war I got drunk with another friend, who works in TV news. We were talking about how—as an approach to national security—invading Iraq was … different. I'd moved my family from Washington to New Hampshire. My friend was considering getting his family out of New York. "Don't you hope," my friend said, "that all this has been thought through by someone who is smarter than we are?" It is, however, a universal tenet of democracy that no one is.

Americans hate foreign policy. Americans hate foreign policy because Americans hate foreigners. Americans hate foreigners because Americans are foreigners. We all come from foreign lands, even if we came ten thousand years ago on a land bridge across the Bering Strait. We didn't want anything to do with those Ice Age Siberians, them with the itchy cave-bear-pelt underwear and mammoth meat on their breath. We were off to the Pacific Northwest—great salmon fishing, blowout potluck dinners, a whole new life.

America is not "globally conscious" or "multicultural." Americans didn't come to America to be Limey Poofters, Frog-Eaters, Bucket Heads, Micks, Spicks, Sheenies, or Wogs. If we'd wanted foreign entanglements, we would have stayed home. Or—in the case of those of us who were shipped to America against our will, as slaves, exiles, or transported prisoners—we would have gone back. Events in Liberia and the type of American who lives in Paris tell us what to think of that.

Being foreigners ourselves, we Americans know what foreigners are up to with their foreign policy—their venomous convents, lying alliances, greedy agreements, and trick-or-treaties. America is not a wily, sneaky nation. We don't think that way. We don't think much at all, thank God. Start thinking and pretty soon you get ideas, and then you get idealism, and the next thing you know you've got ideology, with millions dead in concentration camps and gulags. A fundamental American question is "What's the big idea?"

Americans would like to ignore foreign policy. Our previous attempts at isolationism were successful. Unfortunately, they were successful for Hitler's Germany and Tojo's Japan. Evil is an outreach program. A solitary bad person sitting alone, harboring genocidal thoughts, and wishing he ruled the world is not a problem unless he lives next to us in the trailer park. In the big geopolitical trailer park that is the world today, he does.

America has to act. But, when America acts, other nations accuse us of being "hegemonistic," of engaging in "unilateralism," of behaving as if we're the only nation on earth that counts.

We are. Russia used to be a superpower but resigned "to spend more time with the family." China is supposed to be mighty, but the Chinese leadership quakes when a couple of hundred Falun Gong members do tai chi for Jesus. The European Union looks impressive on paper, with a greater population and a larger economy than America's. But the military spending of Britain, France, Germany, and Italy combined does not equal one third of the U.S. defense budget. The United States spends more on defense than the aforementioned countries—plus Russia plus China plus the next six top defense-spending nations. Any multilateral military or diplomatic effort that includes the United States is a crew team with Arnold Schwarzenegger as coxswain and Nadia Comaneci on the oars. When other countries demand a role in the exercise of global power, America can ask another fundamental American question: "You and what army?"

Americans find foreign policy confusing. We are perplexed by the subtle tactics and complex strategies of the Great Game. America's great game is pulling the levers on the slot machines in Las Vegas. We can't figure out what the goal of American foreign policy is supposed to be.

The goal of American tax policy is avoiding taxes. The goal of American health policy is HMO profits. The goal of American environmental policy is to clean up the environment, clearing away scruffy caribou and seals so that America's drillers for Arctic oil don't get trampled or slapped with a flipper. But the goal of American foreign policy is to foster international cooperation, protect Americans at home and abroad, promote world peace, eliminate human rights abuses, improve U.S. business and trade opportunities, and stop global warming.

We were going to stop global warming by signing the Kyoto protocol on greenhouse gas emissions. Then we realized the Kyoto protocol was ridiculous and unenforceable and that no one who signed it was even trying to meet the emissions requirements except for some countries from the former Soviet Union. They accidentally quit emitting greenhouse gases because their economies collapsed. However, if we withdraw from diplomatic agreements because they're ridiculous, we'll have to withdraw from every diplomatic agreement, because they're all ridiculous. This will not foster international cooperation. But if we do foster international cooperation, we won't be able to protect Americans at home and abroad, because there has been a lot of international cooperation in killing Americans. Attacking internationals won't promote world peace, which we can't have anyway if we're going to eliminate human rights abuses, because there's no peaceful way to get rid of the governments that abuse the rights of people—people who are chained to American gym-shoe-making machinery, dying of gym shoe lung, and getting paid in shoelaces, thereby improving U.S. business and trade opportunities, which result in economic expansion that causes global warming to get worse.

As the nineteenth-century American naval hero Stephen Decatur said in his famous toast: "Our Country! In her intercourse with foreign nations may she always be in the right; but our country, right or wrong, should carry condoms in her purse."

One problem with changing America's foreign policy is that we keep doing it. After the Cold War, President George H. W. Bush managed to engage America—in spite of itself—in the multilateralism of the Gulf War. This left Saddam Hussein exactly where we found him twelve years later. Like other American achievements in multilateralism, it wasn't something we'd care to achieve again. The east side of midtown Manhattan, where a decent slum once stood, is blighted by the United Nations headquarters. And, in the mountains of the Balkan peninsula, the ghost of Woodrow Wilson wanders Marley-like, dragging his chains and regretting the deeds of his life.

President Bill Clinton dreamed of letting the lion lie down with the lamb chop. Clinton kept International Monetary Fund cash flowing into the ever-criminalizing Russian economy. He ignored Kremlin misbehavior from Boris Yeltsin's shelling of elected representatives in the Duma to Vladimir Putin's airlifting uninvited Russian troops into Kosovo. Clinton compared the Chechnya fighting to the American Civil War (murdered Chechens being on the South Carolina statehouse Confederate-flag-flying side). Clinton called China America's "strategic partner" and paid a nine-day visit to that country, not bothering himself with courtesy calls on America's actual strategic partners, Japan and South Korea. Clinton announced, "We don't support independence for Taiwan," and said of Jiang Zemin, instigator of the assault on democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square, "He has vision."

Anything for peace, that was Clinton's policy. Clinton had special peace-mongering envoys in Cyprus, Congo, the Middle East, the Balkans, and flying off to attend secret talks with Marxist guerrillas in Colombia. Clinton made frantic attempts to close an Israeli-Palestinian peace deal. What if the Jews control the Temple Mount and the Arabs control the movie industry? On his last day in office, Clinton was still phoning Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams. "Love your work, Gerry. Do you ever actually kill people? Or do you just do the spin?"

Clinton was everybody's best friend. Except when he wasn't. He conducted undeclared air wars against Serbia and Iraq and launched missiles at Sudan and Afghanistan. Clinton used the military more often than any previous peacetime American president. He sent armed forces into areas of conflict on an average of once every nine weeks.

Then we elected an administration with adults in it— Colin Powell, Dick Cheney, and Donald Rumsfeld. Gone was the harum-scarum Clinton policy-making apparatus with its frenzied bakeheads piling up midnight pizza boxes in the Old Executive Office Building. They disappeared, along with the clinically insane confidants—vein-popping James Carville, toe-sucking Dick Morris—and the loose haircuts in the West Wing and the furious harridan on the White House third floor.

President George W. Bush's foreign policy was characterized, in early 2001, as "disciplined and consistent" (— Condoleezza Rice): "blunt" (—The Washington Post), and "in-your-face" (—the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace). Bush began his term with the expulsion of one fourth of the Russian diplomatic corps on grounds of espionage. He snubbed Vladimir Putin by delaying a first summit meeting until June 2001, and then holding it in fashionable Slovenia.

On April 1, 2001, a Chinese fighter jet, harassing a U.S. reconnaissance plane in international airspace, collided with the American aircraft, which was forced to land in Chinese territory. Bush did not regard this as an April Fools' prank. By the end of the month he had gone on Good Morning America and said that if China attacked Taiwan, the United States had an obligation to defend it.

"With the full force of American military?" asked Charlie Gibson.

"Whatever it took," said Bush.

The president also brandished American missile defenses at Russia and China. The Russians and Chinese were wroth. The missile shield might or might not stop missiles, but, even unbuilt, it was an effective tool for gathering intelligence on Russian and Chinese foreign policy intentions. We knew how things stood when the town drunk and the town bully strongly suggested that we shouldn't get a new home security system.