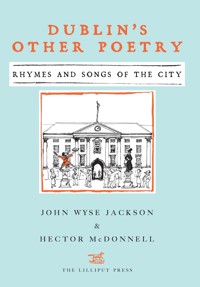

Dublin's Other Poetry E-Book

4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Dublin's writers rarely remain solemn for long: their wicked sense of humour has travelled the world. This is an irresistible new anthology of what used to be called 'comic and curious verse' about the city, written by some of her most entertaining poets and songwriters. Fashions in verse come and go. Too often we forget – paradoxically – the most memorable works of wit, sarcasm or absurdity. The ones gathered here were written over four centuries, and were inspired by many things – among them love, injustice, history, politics, animals and alcohol, but most of all by the citizens of Dublin themselves. Whether the lines are satirical, sentimental, subversive, sexy or just plain silly, you will find that many of them show a rare seriousness as well. Each poem comes with background information about where it originated, and each page is illuminated by Hector McDonnell's wonderful, witty drawings.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

DUBLIN’S OTHER POETRY

Rhymes and Songs of the City

Edited by John Wyse Jacksonand Hector McDonnell

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

The book is dedicated, with love, to Eoghan Mitchell and Rose McDonnell.

Contents

(Verses are arranged alphabetically by author or, if anonymous, by title. Inverted commas denote working titles supplied for this edition.)

Title Page

Dedication

Rhymes and Reasons: An Introduction

Allen, Fergus, To Trinity College, 1943

Allt, Peter, Poem

Balbriggan: At the Ladies’ Bathing Place (Anon.)

Behan, Brendan, The Old Triangle

Bonass, George, A Ballade of the Future

A Stout Saint

Caprani, Vincent, The Dubliner

Gough’s Statue

Choriambics from Carlisle Bridge (Anon.)

Craig, Maurice James, Kilcarty to Dublin

Curran, John Philpot, The Monks of the Screw

Daiken, Leslie, Les Jeunes à James Joyce

Dockrell, Morgan, Awkcents

Dollymount Strand (Anon.)

Donnybrook Fair: an Irregular Ode (Anon.)

Egan, M.F., Mystic Journey

Enquiring Edward (Anon.)

Epitaph (Anon.)

FitzGerald, Herbert G., Twice Nightly

The Graftonette, 1916

Fitzgerald, Mick, Me Brother’s a TD

French, Percy, A Case of Etiquette

The German Clockwinder (Anon.)

Gillespie, Leslie, Marching through Georgia

Gogarty, Oliver St John, The Hay Hotel

The Grand Canal (Anon.)

Guinness, Bryan, The Axolotl

Handcuffs for Two Wrists (Anon.)

The Hermit (Anon.)

Higgins, F.R., The Old Jockey

Irwin, T.C., A Lament for Donnybrook

It was at Darling Dublin (Anon.)

Jemmy O’Brien’s Minuet (Anon.)

Jones, Paul, A Plea for Nelson Pillar

Keegan, Charlie, Ode to a Giant Snail Found in a Dublin Garden

A Kind Inquirer (Anon.)

Ledwidge, Francis, The Departure of Billy the Bulldog

MacDonald, William Russell, A New Irish Melody

MacManus, M.J., Remembrance

Eden Quay

A Lament for the Days that are Gone

The Maid of Cabra West (Anon.)

Mathews, M.J.F., and Allen, Fergus, ‘An Exchange’

Milne, Ewart, The Ballad of Ging Gong Goo

Molly Malone (Anon.)

Murrough O’Monaghan (Anon.)

O’Connell Bridge (Anon.)

O’Flaherty, Charles, The Aeronauts

O’Meara, Liam, Moving Statues

Paddy’s Trip from Dublin (Anon.)

An Philibín, In Petto

The Rakes of Stony Batter (Anon.)

Saint Patrick (Anon.) and ‘Far Westward’

Sall of Copper-Alley (Anon.)

Sandymount Strand (Anon.)

Sayers, Dorothy L, ‘If …’

Shaw, George Bernard, ‘At Last I Went to Ireland’

Sheridan, Thomas, The Tale of the T[ur]d

‘An Invitation’

On The Revd Dr Swift (attrib.)

Smith, Daragh, The Sea Baboon

Brian Boru’s French Letter

Smythe, Colin, Ode to Sally Gardiner

The Song of the Liffey Sprite (Anon.)

The Spanish Lady (Anon.)

Stoney Pocket’s Auction (Anon.)

Swift, Jonathan, Cantata

Dean Swift’s Grace (attrib.)

‘Epitaph on John Whalley’ (attrib.)

Three Blind Mice (Anon.)

Thriller (Anon.)

Trench, J.G.C., The Sensible Sea-Lion

Varian’s Brushes (Anon.)

Weston, R.P., and Barnes, F.J., I’ve Got Rings on My Fingers

White, Terence De Vere, Onwards

The Wild Dog Compares Himself to a Swan (Anon.)

Williams, Richard D’Alton, Quodded

Zozimus, The Address of Zozimus to his Friends

The Last Words of Zozimus

Acknowledgments and Thanks

Index of Titles and First Lines

About the Author

Copyright

Rhymes and Reasons: An Introduction

We are very happy indeed to present Dublin’s Other Poetry to our ravenous readers. It is a sequel to our last volume, Ireland’s Other Poetry: Anonymous to Zozimus (2007), an anthology of Irish humorous poetry which drew material from all corners of the island, as well as from four centuries of history. Inevitably, there were several poems and songs about Dublin in it, but we are particularly proud of the fact that we have found so much good material that none of the ones from the first volume is repeated here. We hope you will discover many new favourites as well as a few unexpected twists to some old friends among the verses we have chosen for this collection.

What on earth, you may reasonably ask, do we mean by ‘Other Poetry’? The simplest answer is to suggest that you browse through the pages of this book. You will meet parodies, ballads, mock-heroic metrical narratives, bawdy odes, political and personal satires, unashamed doggerel, drinking songs, old-style light verse, comic recitations and even advertising copy for Dublin’s most famous product, Guinness, in addition to a clutch of curiosities that defy categorization. Now and again you may even encounter the deep note of true poetry, but we trust that you will find that all the entries are resolutely unpretentious, and that they also share a common purpose – a belief that life may be quite good fun. You will also notice (we hope) that almost every entry here uses metre and rhyme.

‘The troublesome and modern bondage of Rhyming,’ wrote John Milton in his preface to Paradise Lost, is ‘no necessary adjunct or true ornament of poem or good verse … but the invention of a barbarous age, to set off wretched matter and lame metre.’ Poets of the modern age have tended to agree with him: no longer are they expected to upset the fluency of their minstrelsy by going through an agonizing search for a rhyme for ‘silver’ or ‘orange’. Milton, however, would probably have been distressed to discover that most of today’s poets have also ditched the old, highly skilled practice of metrical prosody. Sometimes, admittedly, this has been replaced by a loose, vaguely rhythmical beat, but many contemporary poems can be distinguished from some weird form of prose only by an extravagantly low ratio of words per page and a certain preciousness of diction. These days, the antiquated fripperies of rhyme and metre are generally reserved for less high-minded endeavours – in short, for exactly what we have christened ‘Other Poetry’.

Happily Dublin has a long history of this sort of ‘unserious’ versemaking. The earliest poems in these pages come from the eighteenth century, the time of Jonathan Swift, Thomas Sheridan and their successors, who built up a lively habit of satirical verse. This form of educated satire ran in tandem with another, less polished, body of work by urban balladeers, dealing with city realities that were totally ignored by all other chroniclers, such as that anonymous sequence of macabre recitations of which the most famous is ‘De Night before Larry was Stretch’d’.

Dublin’s growing middle classes were soon adding new literary spices to this stew, and creating their own varieties of occasional verse, some of which even got into print. Various irreverent books such as Pranceriana and The Parson’s Horn-book appeared, poking fun in mock-heroic couplets at any august figures that deserved derision, such as particularly pompous provosts of Trinity College or bishops of the Established Church. Convivial societies were founded which held regular meetings in town to ‘quaff the flowing bowl’ and exchange their latest poetic offerings. Needless to say these were not always of the highest quality. On top of these delights, in the early decades of the nineteenth century, periodicals came and went too, like Grant’s Almanack, the Comet, Paddy Kelly’s Budget and the Dublin Satirist. There you could catch up on the latest gossip and scandal and try to make sense of their riddles, rhymes and rebuses. Apparently readers were hugely tickled by these anonymous effusions, though not much in these journals seems likely to tickle anyone’s fancy today, not even the contributions of a youthful James Clarence Mangan. Indeed, to modern eyes, most of the wit in these books and papers has quietly curled up and died, and so we have not burdened this collection with very much from them, entertaining though they must have seemed at the time.

There was however a much more creative printing industry operating in nineteenth century Dublin and catering for a mass public with less rarefied tastes. From the back rooms of bookshops and junkshops one-man presses poured forth a stream of crudely printed broadsheets bearing new and old songs, ballads and comic poems. This was the milieu of Dublin’s most famous old ballad singer, Zozimus – a small selection of whose work rounds off this volume, as it did the last. Cheap pamphlets were also churned out with the lyrics of the latest hits of the season, as performed on stage at variety shows in the Theatre Royal and elsewhere. Many of these songs and recitations were English imports, but Dublin compositions were equally popular, including the anonymous ‘Stoney Pocket’s Auction’, a ballad that itself explores this alternative Irish mythopoeia of song. (It may be found below on page 115.)

As time went by, and the habit of reading spread, the second half of the nineteenth century saw a succession of comic magazines in Dublin – Pat’s Paper, Zozimus and a dozen others. Usually written by small groups of like-minded friends, few of them lasted long, but they often contained witty excursions in verse, offering rare insights into changing moods in the Irish capital during the half-century that led up to independence. Just about the last magazine in that mould was Dublin Opinion, which began with the foundation of the state in 1922, and it was by far the best of the lot. Some verses from that paper appear in Ireland’s Other Poetry, and a couple more have found their way into this volume too, as well as some spirited examples from some of its Victorian predecessors.

During the twentieth century, several writers, both amateur and professional, have found outlets for their ‘Other Poetry’. During the 1920s, for instance, George Bonass, a career civil servant, was given a regular spot for his occasional verse in the Dublin Evening Mail, while the journalist M.J. MacManus had various collections of his rhymes and parodies published in book form. At both Trinity College and University College, Dublin, undergraduates contributed verses to student magazines, and TCDMiscellany in particular was so productive that a book of the best of it was issued in 1945, and sold well. Several of these student scribblers later became celebrated for quite different achievements, including the late Conor Cruise O’Brien. He had copious quantities of light verse published in TCD Miscellany, but it was all so topically allusive that only detailed annotations would make it comprehensible today, and in the process half the fun would melt away. So, alas, nothing by the Cruiser appears here. Happily, however, the book opens with a TCD poem by one of his near contemporaries, Fergus Allen, now one of our most admired ‘proper’ poets.

Chance has played a large part in the survival of certain strands of ‘Dublin’s Other Poetry’, such as the off-colour verses that have always circulated by word of mouth through the city. The ruderies of Oliver St John Gogarty were eventually collected in book form, and so too were Daragh Smith’s almost legendary ‘medical verses’ (two of which are in this collection), but it is now very difficult to locate other similarly ephemeral verses, many of which may not even have been written down. The following snatch of Dublin ribaldry, for example, would almost certainly have been lost to posterity if James Joyce hadn’t put it into Ulysses, where Molly Bloom remembers hearing some lads chanting it one day at the corner of Marrowbone Lane. It is of course a riddle, about repairing a sweeping-brush:

My Uncle John

Has a thing long,

My Aunt Mary

Has a thing hairy,

And he puts his thing long

Into my Aunt Mary’s

Hairy …

On the flyleaf of Ireland’s Other Poetry we asked readers to tell us about any further interesting verses, ephemeral or otherwise, that they felt we ought to have put in the book. We are grateful to the many kind people who sent us suggestions (including, in some cases, their own compositions). Several of these discoveries appear in this volume, and more may be read on a webpage that we set up for the purpose, which can be visited at http://irelandsotherpoetry. spaces.live.com. If you know of anything good that we may have overlooked, we would still be delighted to hear from you by email at [email protected].

Gathering and organizing material for this book has once again been a very happy task for both editors. Hector has enjoyed making his drawings to illuminate the verses, and John has enjoyed looking at them. When the previous volume appeared, one reviewer was disappointed that we hadn’t included an essay tracing the origins and history of ‘Ireland’s Other Poetry’. You won’t find one in this book either, so we will all have to wait until a full academic treatment of the subject is eventually written by somebody else. In the meantime, if you are pining for literary history, we have tried to supply in the headnotes a little more information about the poets and their work than we did in the first book. As before, the entries are arranged alphabetically by author, or by title where the author is unknown to us, and there is an index of titles and first lines at the back of the book.

John Wyse Jackson Hector McDonnell

DUBLIN’S OTHER POETRY

Fergus Allen

What we mean by ‘Other Poetry’ remains something of a movable feast, but one branch of it is certainly light verse. Lately this has fallen into disrepute, perhaps because too often it degenerates into throwaway doggerel. But along with wit, successful light verse demands a high degree of technical skill as well. The real powerhouse of this sort of poetry in twentieth-century Ireland was Trinity College Dublin, so it is pleasing that we can begin our alphabet with an excellent example fromTCD Miscellany in the 1940s. The decade was probably the light-verse heyday of that most exceptional undergraduate magazine.

Fergus Allen (b. 1921) is far more than a composer of light verse, of course. As a prizewinning ‘proper poet’ he has issued four fine collections of his work in the last two decades, and we are duly grateful to him for allowing us to pluck this apprentice piece from obscurity.

The verses were an ironic reply to a recent article in the paper about Trinity’s place in modern Ireland:

It is not, to be sure, easy to change a tradition that has run in a single groove for centuries … It is well to be reminded once in a while that T.C.D. possesses a Gaelic Society … Trinity can, if it rids itself of ancient prejudices and outworn ideas, play no small part in this great national work.

– Irish Press, November 23, 1943.

TO TRINITY COLLEGE, 1943

Four hundred years have well-nigh passed,

The shades of night are falling fast,

Can aught avail our noble caste,

My Trinity?

This place where Art and Science wed,

Where scholars stalk and angels tread

And join to praise the mighty dead

Of Trinity!

Where shapes of things to come are shaped,

Where locks are neither picked nor raped—

The Gaelic League has got us taped,

My Trinity!

They soon will come, a Celtic rout,

Athirst for blood, incensed with stout,

To throw our foreign culture out,

My Trinity!

Is this the working of the curse,

Is this the Anglo-Irish hearse,

To hear the natives speaking Erse

In Trinity?

With curling lip and scornful eye

We hear the Gaelic hue and cry,

We watch the peasants passing by,

From Trinity!

Our sneer of cold command still quells,

We’ve got the savoir-vivre that tells,

We’ve got the blasted Book of Kells,

In Trinity!

Spirit of Cromwell! Rise again

And subjugate by sword or pen

These rude, uncouth, untutored men

To Trinity!

Peter Allt

Behind these atmospheric lines lurks Molière’s play, Les Precièuses Ridicules, a satire on Mme Rambouillet’s ‘salon bleu’ in early seventeenth-century Paris. When the elegant and gifted Peter Allt (1917–54) wrote them in the late 1930s, he still had his major work on Yeats’s poetry ahead of him, but would already have been quite a catch for any of Dublin’s literary ‘at-homes’. Quite an aesthete himself, Allt had a provocative turn of phrase – he once compared Patrick Kavanagh and other ‘revolutionary’ Irish poets like him to ‘coal-heavers at a sherry party’. He died tragically young, in a railway accident.

POEM

Ghost of a ghost of Madame Rambouillet

Presiding like a blanket in the room,

My wings well clipped; tongue clipped; perforced to stay

I smile like one who has foreseen his doom,

Or a cynic faute de mieux accepts a destined tomb.

My lady hostess polymath advances

(On charm and sausages her poets fed),

Sidles, with twisted neck, and sidelong glances

‘And what is it you do, my dear?’ I shake a golden head

Glumly; and wonder why the paths of glory

Lead (so monotonously) to a double-bed.

Scented, tattooed, and clad in velvet breeches

I am engulfed with Baudelaires and Nietzsches.

Sandals and sweaters, purple shirts, green bows,

Marlowes pursue me, Michelangelos.

Anonymous

The nineteenth century saw many periodicals come and go in Dublin. Ireland’s Other Poetry (this book’s predecessor) found several good verses in Richard Dowling’s light satirical magazine of the early 1870s, Zozimus – named after the Dublin balladeer who became our book’s patron saint.

Ten years later, Zozimus had folded, but a similar humorous journal, Pat’s Komik, usually known simply as Pat, was being produced by W.P. Swan ‘at the Carlton Steam Printing Works, 9 William Street’. There, the resident poet (or band of poets – contributors were strictly anonymous) presented an occasional series of lively odes, called ‘Lyra Liffeiana’, about celebrated spots in and around the city. Some of the best (or oddest) of them are reprinted in this volume. This one, a frothy, briny confection about the popular northside resort of Balbriggan, appeared in Pat on 9 September 1882.

BALBRIGGAN: AT THE LADIES’ BATHING PLACE

By this town so famed for hoses,

Where the seaweed thickly growses,

Summer zephyrs softly blowses,

Yachts with sails as white as snowses,

Or at anchor safe reposes,

Fishing smacks as black as crowses,

Or little pigs with trichinosis

(Not the nasty smacks you knowses,

That elicit cries of woeses,

When they tingle on elbowses),

But the sort we sometimes rowses,

Where the tide it ebbs and flowses,

Right upon your back you goeses,

Nothing seen but knees and noses,

And ten funny little toeses,

Fishes flat with eyes like sloeses,

Blush as rubies red or roses,

Saying ‘Oh! what shocking showses!’

Vulgar crabs cry ‘Hokey Moses,

Where in goodness are their clotheses?’

Brendan Behan

Brendan Behan (1923–64) set little store by literary copyright, at least where others were concerned. His memory, under siege though it often was, retained countless verses and songs from many sources. Some of these he adapted for recycling in the normal literary way, but more often he changed them spontaneously during performance. The suspicion remains, therefore, that he was not in fact the originator of the song below; however he was certainly the one who made it familiar: his best play, The Quare Fellow, can hardly be imagined without it.

THE OLD TRIANGLE

A hungry feeling

Came o’er me stealing

And the mice were squealing in my prison cell,

And that old triangle

Went jingle jangle

Along the banks of the Royal Canal.

To begin the morning

The warder bawling

‘Get out of bed and clean out your cell,’

And that old triangle

Went jingle jangle

Along the banks of the Royal Canal.

On a fine spring evening,