30,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

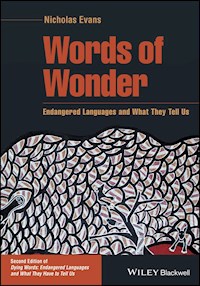

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Language Library

- Sprache: Englisch

The next century will see more than half of the world’s 6,000 languages become extinct, and most of these will disappear without being adequately recorded. Written by one of the leading figures in language documentation, this fascinating book explores what humanity stands to lose as a result.

- Explores the unique philosophy, knowledge, and cultural assumptions of languages, and their impact on our collective intellectual heritage

- Questions why such linguistic diversity exists in the first place, and how can we can best respond to the challenge of recording and documenting these fragile oral traditions while they are still with us

- Written by one of the leading figures in language documentation, and draws on a wealth of vivid examples from his own field experience

- Brings conceptual issues vividly to life by weaving in portraits of individual ‘last speakers’ and anecdotes about linguists and their discoveries

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 634

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Acknowledgments

Publishing and Copyright Acknowledgments

Text Credits

Figure Credits

Prologue

Further Reading

A Note on the Presentation of Linguistic Material

Part I: The Library of Babel

1 Warramurrungunji’s Children

Language Diversity and Human Destiny

Language Diversity through Time and Space

Where the Hotbeds Are

The Wellsprings of Diversity in Language, Culture, and Biology

Words on the Land

Further reading

2 Four Millennia to Tune In

An Incident at Mount Bradshaw

The Story of A

What Ovid Did in His Exile

Speaking to Other Hearts and Minds

Listening to the Word, Listening to the World

Glyphs, Wax Cylinders, and Videos

Further reading

Part II: A Great Feast of Languages

3 A Galapagos of Tongues

The Unbroken Code

Sounds Off

Knowing the Giving from the Gift

The Great Chain of Being

Further reading

4 Your Mind in Mine: Social Cognition in Grammar

Further reading

Part III: Faint Tracks in an Ancient Wordscape: Languages and Deep World History

5 Sprung from Some Common Source

The Careless Scribes

Back to the Old Wording: How the Comparative Method Works

Every Witness Has Part of the Story

Synchrony’s Poison Is Diachrony’s Meat

By the Waters of Lake Chad

Loanwords as Complication and Resource

The Linguistic Lens on the Past

Further reading

6 Travels in the Logosphere: Hooking Ancient Words onto Ancient Worlds

Tongue to Tongue: Localizing Languages One to Another

Words to Things: Matching Vocabularies to Archaeological Finds

Name on Place: the Evidence of Toponyms

Argonauts of Two Oceans

Long-Lost Subarctic Cousins

Lungo Drom: the Long Road

Further reading

7 Keys to Decipherment: How Living Languages Can Unlock Forgotten Scripts

Outwitting the Conquering Barbarians

Dying a Second Death

The Keys to Decipherment

Reading the Clear Dawn: Mayan Then and Now

Released by Flames: The Case of Caucasian Albanian

Zoquean Languages and the Epi-Olmec Script

Darkening Pages

Further reading

Part IV Ratchetting Each Other Up: The Coevolution of Language, Culture, and Thought

8 Trellises of the Mind:

The Linguistic Relativity Hypothesis and Its Precursors

How Closely Coupled

Move This Book a Bit to the South

The Flow of Action in Language and Thought

Blicking the Dax: How Different Tongues Grow Different Minds

Language and Thought: A Burgeoning Field

Further reading

9 What Verse and Verbal Art Can Weave

Extraordinary Language

Carving with the Grain

Improbable Bards and Epic Debates: the Singers of Montenegro

The Case of Khlebnikov’s Grasshopper

Unsung Bards of the New Guinea Highlands

No Spice, No Savor

The Great Semanticist Yellow Trevally Fish

An Oral Culture Always Stands One Generation Away from Extinction

Further reading

Part V: Listening While We Can

10 Renewing the Word

The Process of Language Shift

Let Us, Ciphers to This Great Account…18

Bringing It Out and Laying It Down

From Clay Tablets to Hard Drives

Further reading

Epilogue: Sitting in the Dust, Standing in the Sky

Notes

References

Websites

Both

Index of Languages and Language Families

Index

THE LANGUAGE LIBRARY

Series editor: David Crystal

The Language Library was created in 1952 by Eric Partridge, the great etymologist and lexicographer, who from 1966 to 1976 was assisted by his co-editor Simeon Potter. Together they commissioned volumes on the traditional themes of language study, with particular emphasis on the history of the English language and on the individual linguistic styles of major English authors. In 1977 David Crystal took over as editor, and The Language Library now includes titles in many areas of linguistic enquiry.

The most recently published titles in the series include:

Ronald Carter and Walter Nash Seeing Through Language Florian Coulmas The Writing Systems of the World David Crystal A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics, Sixth Edition J. A. Cuddon A Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory, Fourth Edition Viv Edwards Multilingualism in the English-speaking World Nicholas Evans Dying Words: Endangered Languages and What They Have to Tell Us Amalia E. Gnanadesikan The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet Geoffrey Hughes A History of English Words Walter Nash Jargon Roger Shuy Language Crimes Gunnel Tottie An Introduction to American English Ronald Wardhaugh Investigating Language Ronald Wardhaugh Proper English: Myths and Misunderstandings about LanguageThis edition first published 2010

© 2010 Nicholas Evans

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148–5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Nicholas Evans to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks, or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Evans, Nicholas, 1956–

Dying words: endangered languages and what they have to tell us/Nicholas Evans.

p. cm. – (Language library)

Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

ISBN 978-0-631-23305-3 (alk. paper) – ISBN 978-0-631-23306-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Endangered languages. I. Title. II. Series.

P40.5.E53E93 2009

408.9–dc22

for my parents and children, by blood and by teaching

Acknowledgments

My first debt is to the speakers of fragile languages who have welcomed me into their communities and their ways of talking, thinking, and living. †Darwin and May Moodoonuthi adopted me as their tribal son in 1982 and they and the rest of the Bentinck Island community taught me their language as if I were a new child. The community has extended its love and understanding to me and my wife and children ever since, despite the tragically premature deaths of so many of its members. I particularly thank †Darwin Moodoonuthi, †Roland Moodoonuthi, †Arthur Paul, †Alison Dundaman, †Pluto Bentinck, †Dugal Goongarra, †Pat Gabori, †May Moodoonuthi, Netta Loogatha, †Olive Loogatha, Sally Gabori, and Paula Paul. Since 1982 I have had the good fortune to be taught about other Aboriginal languages by †Toby Gangele, †Minnie Alderson, Eddie Hardie, †Big John Dalnga-Dalnga, and †Mick Kubarkku (Mayali, Gun-djeihmi, Kuninjku, and Kune dialects of Bininj Gun-wok), †David Kalbuma, †Alice Boehm, †Jack Chadum, †Peter Mandeberru, Jimmy Weson, and Maggie Tukumba (Dalabon), †Charlie Wardaga (Ilgar), †Mick Yarmirr (Marrku), †Tim Mamitba, †Brian Yambikbik, Joy Williams, Khaki Marrala, Mary Yarmirr, David Minyumak, and Archie Brown (Iwaidja). Each of these people, and many others too numerous to name and thank individually here, is linked in my mind to vivid and powerful moments as, in their own resonant languages, they discussed things I had never attended to or thought about before.

I would also like to thank my teachers and mentors in linguistics for the way they have imbued the field with fascination and insight: Bob Dixon, Bill Foley, Igor Mel’cuk, †Tim Shopen, and Anna Wierzbicka during my initial studies at the Australian National University, and more recently Barry Blake, Melissa Bowerman, Michael Clyne, Grev Corbett, Ken Hale, Lary Hyman, Steve Levinson, Francesca Merlan, Andy Pawley, Frans Plank, Ger Reesink, Dan Slobin, Peter Sutton, and Alan Rumsey. Many of the ideas touched upon here have developed during conversations with my colleagues Felix Ameka, Alan Dench, Janet Fletcher, Cliff Goddard, Nikolaus Himmelmann, Pat McConvell, Tim McNamara, Rachel Nordlinger, Kia Peiros, Lesley Stirling, Nick Thieberger, Jill Wigglesworth, and David Wilkins, my students Isabel Bickerdike, Amanda Brotchie, Nick Enfield, Sebastian Olcher Fedden, Alice Gaby, Nicole Kruspe, Robyn Loughnane, Aung Si and Ruth Singer, and my fellow fieldworkers Murray Garde, Bruce Birch, Allan Marett, and Linda Barwick.

In putting this book together I have been overwhelmed by the generosity of scholars from around the world who have shared with me their expertise on particular languages or fields, and I thank the following: Abdul-Samad Abdullah (Arabic), Sander Adelaar (Malagasy and Austronesian more generally), Sasha Aikhenvald (Amazonian languages) Linda Barwick (Arnhem Land song language), Roger Blench (various African languages), Marco Boevé (Arammba), Lera Boroditsky (various Whorfian experiments), Matthias Brenzinger (African languages), Penny Brown (Tzeltal), John Colarusso (Ubykh), Grev Corbett (Archi), Robert Debski (Polish), Mark Durie (Acehnese), Domenyk Eades (Arabic), Carlos Fausto (Kuikurú), David Fleck (Matses), Zygmunt Frajzyngier (Chadic), Bruna Franchetto (Kuikurú), Murray Garde (Arnhem Land clans and languages), Andrew Garrett (Yurok), Jost Gippert (Caucasian Albanian), Victor Golla (Pacific Coast Athabaskan), Lucia Golluscio (indigenous languages of Argentina), Colette Grinevald (Mayan, languages of Nicaragua), Tom Güldemann (Taa and Khoisan in general), Alice Harris (Udi), John Haviland (Guugu Yimithirr, Tzotzil), Luise Hercus (Pali and Sanskrit), Jane Hill (Uto-Aztecan), Kenneth Hill (Hopi), Larry Hyman (West African tone languages), Rhys Jones (Welsh), Russell Jones (Welsh), Anthony Jukes (Makassarese), Dagmar Jung (Athabaskan), Jim Kari (Dena’ina), Sotaro Kita (gesture in Japanese and Turkish), Mike Krauss (Eyak), Nicole Kruspe (Ceq Wong), Jon Landaburu (Andoke), Mary Laughren (Wanyi), Steve Levinson (Guugu Yimithirr, Yélî-Dnye), Robyn Loughnane (Oksapmin), Andrej Malchukov (Siberian languages), Yaron Matras (Romani), Peter Matthews (Mayan epigraphy), Patrick McConvell (various Australian), Fresia Mellica Avendaño (Mapudungun), Cristina Messineo (Toba), Mike Miles (Ottoman Turkish Sign Language), Marianne Mithun (Pomo, Iroquoian), Lesley Moore (Mandara Mountains), Valentín Moreno (Toba), Claire Moyse-Faurie (New Caledonian languages), Hiroshi Nakagawa (−Gui), Christfried Naumann (Taa), Irina Nikolaeva (Siberian languages), Miren Lourdes Oñederra (Basque), Mimi Ono (−Gui, and Khoisan generally), Toshiki Osada (Mundari), Nick Ostler (Aztec, Sanskrit and many others), Midori Osumi (New Caledonian languages), Aslı Özyürek (Turkish gesture, Turkish Sign Language), Andy Pawley (Kalam), Maki Purti (Mundari), Valentin Peralta Ramirez (Nahuatl/Aztec), Bob Rankin (Siouan), Richard Rhodes (Algonquian), Malcolm Ross (Oceanic languages), Alan Rumsey (Ku Waru, New Guinea Highlands chanted tales), Geoff Saxe (Oksapmin counting), Wolfgang Schulze (Caucasian Albanian/Udi), Peter Sutton (Cape York languages), McComas Taylor (Sanskrit), Marina Tchoumakina (Archi), Nick Thieberger (Vanuatu languages, digital archiving), Graham Thurgood (Tsat and Chamic), Mauro Tosco (Cushitic), Ed Vajda (Ket and other Yeniseian), Rand Valentine (Ojibwa), Dave Watters (Kusunda), Kevin Windle (Slavic), Tony Woodbury (Yup’ik), Yunji Wu (Chinese), Roberto Zavala (Oluteco, Mixe-Zoquean), Ulrike Zeshan (Turkish Sign Language).

A special thanks to those who arranged for me to visit or meet with speakers of a wide range of languages around the world as I researched this book: Zarina Estrada Fernandez (northern Mexico), Murray Garde (Bunlap Village, Vanuatu), Andrew Garrett (Yurok, northern California), Lucia Golluscio (Argentina), Nicole Kruspe (Pos Iskandar and Bukit Bangkong, Malaysia), the Mayan language organization OKMA and its director Nik’t’e (María Juliana Sis Iboy) in Antigua, Guatemala, Patricia Shaw (Musqueam Community in Vancouver), and especially Roberto Zavala and Valentín Peralta Ramirez for a memorable journey down through Mexico to Guatemala. Not all these stories made it through to the final, pruned manuscript, but they all shaped its spirit.

A number of institutions and programs have given me indispensable support in researching and writing this book: the University of Melbourne, the Australian National University, the Institut für Sprachwissenschaft, Universität Köln, the Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung, CIESAS (Mexico), OKMA (Guatemala), and the Universidad de Buenos Aires. Two other organizations whose ambitious research programs have enormously expanded my horizons are the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, and the Volkswagenstiftung through its DoBeS Program (Dokumentation Bedrohter Sprachen) and in particular for its support of the Iwaidja Documentation Program. In this connection, I thank Vera Szoelloesi-Brenig for her wise stewardship of the overall program, and many participants in the DoBeS program, especially Nikolaus Himmelmann, Ulrike Mosel, Hans-Jürgen Sasse, and Peter Wittenberg, for formative discussions.

The process of putting these obscure and disparate materials together into a coherent book directed at a broad readership would have been impossible without the generous support of two one-month residencies in Italy, one in Bellagio sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation, and a second in Bogliasco sponsored by the Bogliasco Foundation. I thank these two foundations for their wonderfully humanistic way of supporting creative work, and in particular would like to thank Pilar Palacia (Bellagio) and Anna Maria Quaiat, Ivana Folle, and Alessandra Natale (Bogliasco) for their hospitality and friendship, as well as the other residents for their many clarifying discussions.

Publication of this work was assisted by a publication grant from the University of Melbourne, as well as further financial support from the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, and I thank both institutions for their generous support.

At various points along the way Amos Teo and Robert Mailhammer checked the text and chased up materials, cartographers Chandra Jayasuriya (University of Melbourne) and Kay Dancey (Cartographic Services, RSPAS, Australian National University) produced the maps, Julie Manley assisted with many of the visuals, and Felicita Carr gave indispensable help in obtaining permissions on getting the final version of a sprawling manuscript together. Without them this book would still be a draft.

A number of people read and commented on drafts of the entire manuscript and I thank them for their perceptive comments and advice: Michael Clyne, Jane Ellen, Lloyd Evans, Penny Johnson, Andrew Solomon, and Nick Thieberger. David Crystal also read the entire manuscript, and gave invaluable writerly advice and support through the many years of this project’s gestation: diolch yn fawr! I am also grateful to Melissa Bowerman for her careful comments on an earlier version of chapter 8. Two anonymous reviewers for Blackwell also blessed me with incredibly detailed, helpful, and erudite comments.

The staff at Wiley-Blackwell have been a model of supportive professionalism, although my laggardliness has meant the project has needed to be passed through a large number of individuals: I thank Tami Kaplan, Kelly Basner, and Danielle Descoteaux.

Publishing and Copyright Acknowledgments

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the copyright material in this book. The following sources and copyright holders for materials are given in order of appearance in the text.

Text Credits

Fishman, Joshua. 1982. Whorfianism of the third kind: ethnolinguistic diversity as a worldwide societal asset. Language in Society 11:1–14. Quote from Fishman (1982:7) reprinted with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Rogers, Henry. 2005. Writing Systems: A Linguistic Approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. Material in table 2.1 herein reprinted with permission of the author and Wiley-Blackwell.

Cann, Rebecca. 2000. Talking trees tell tales. Nature 405(29/6/00):1008–9. Quote from Cann (2000:1009) reprinted with permission of Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Levinson, Stephen C. 2003. Space in Language and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Levinson’s figure 4.11 (p. 156) reproduced here as figure 8.3 with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Brown, Penelope. 2001. Learning to talk about motion UP and DOWN in Tzeltal: is there a language-specific bias for verb learning? In Language Acquisition and Conceptual Development, ed. Melissa Bowerman and Stephen C. Levinson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 512–43. The second half of Brown’s figure 17.2 (p. 529) reproduced here as table 8.2 with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Woodbury, Anthony. 1998. Documenting rhetorical, aesthetic and expressive loss in language shift. In Endangered Languages: Current Issues and Future Prospects, ed. L. A. Grenoble and L. J. Whaley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 234–60. Quotes from Woodbury (1998:250, 257) reprinted with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Hale, Ken. 1998. On endangered languages and the importance of linguistic diversity. In Endangered Languages: Current Issues and Future Prospects, ed. L. A. Grenoble and L. J. Whaley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 192–216. Quote from Hale (1998:211) reprinted with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Other copyright holders are acknowledged in the text, as appropriate.

Figure Credits

Photo in box 1.1 courtesy of Leslie Moore.

Figure 1.4 from Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona, James Manson (photographer), JWM ASM-25114, reproduced with permission of the Arizona State Museum.

Figure 2.1 from Florida Center for Instructional Technology, University of South Florida, http://etc.usf.edu/clipart/25300/25363/sahagun_25363.htm.

Figure 2.2 no. 14, part XI, p. 62 from the Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, Book 10: The People, translated from the Azetec into English, with notes and illustration, by Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O. Anderson (Santa Fe, NM/Salt Lake City: the School of American Research and the University of Utah, 1961), reproduced with permission of the University of Utah Press.

Figure 2.3 from the American Philosophical Society, Franz Boas Papers, Collection 7. Photographs.

Figure 2.4 reproduced with permission of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution (neg. no. 8300).

Figure 2.5 p. 53 in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 17: Languages, ed. Ives Goddard (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1996).

Figure 2.6 courtesy Turk Kulturune Hizmet Vakfi.

Figure 3.1 photo courtesy US National Archives, originally from US Marine Corps, No. 69889-B.

Figure 3.2 photo courtesy of Christfried Naumann.

Photo in box 3.1 from Georges Dumézil, Documents Anatoliens sur les Langues et les Traditions du Caucase, Vol. 2: Textes Oubykhs (Paris: Institut d’Ethnologie, 1962).

Figure 3.3 p. 104 in Nancy Munn, Walbiri Iconography: Graphic Representations and Cultural Symbolism in a Central Australian Society (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973), reprinted with permission.

Photo in box 3.2 by kind permission of Geoff Saxe.

Figure 4.1 photo courtesy of David Fleck.

Figure 5.1 illustration 3b in Alexander Murray, Sir William Jones 1746-1794: A Commemoration (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

Photo in box 5.1 courtesy of Michael Krauss.

Figure 6.4 pp. 77, 96, 218, and 220 in The Lexicon of Proto-Oceanic: Volume 1, Material Culture, ed. Malcolm D. Ross, Andrew Pawley, and Meredith Osmond (Canberra: Australian National University, 1998), reprinted with permission. Original spatula drawings p. 226 in Hans Nevermann, Admiralitäts-Inseln in Ergebnisse der Südsee-Expedition 1908–1910, ed. G. Thilenus, vol. 2 A3 (Hamburg: Friederichsen, De Gruyter & Co, 1934).

Table 6.3 adapted, with permission, from pp. 96–7 in The Lexicon of Proto-Oceanic: Volume 1, Material Culture, ed. Malcolm D. Ross, Andrew Pawley, and Meredith Osmond (Canberra: Australian National University, 1998).

Figure 6.6 reproduced with kind permission of H. Werner.

Figure 7.1 British Library Photo 392/29(95). © British Library Board. All rights reserved 392/29(95). Reproduced with permission.

Figure 7.2 p. 6 in Richard Cook, Tangut (Xīxià) Orthography and Unicode (2007). Available online at http://unicode.org/~rscook/Xixia/, accessed May 13, 2008.

Figure 7.4 figure 3, pp. 1–16, in Stephen D. Houston and David Stuart, “The way glyph: evidence for ‘co-essences’ among the Classic Maya,” Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 30 (Washington: Center for Maya Research, 1989). Reproduced with permission.

Figure 7.6 frontispiece in George H. Forsyth and Kurt Weitzmann, with Ihor Ševčenko and Fred Anderegg, The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Church and Fortress of Justinian, Plates (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1973).

Figure 7.7 adapted, with permission, from Zaza Alexidze and Betty Blair, “The Albanian script: the process – how its secrets were revealed,” Azerbaijan International 11/3:44–51 (2003). Available online at www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/ai113_folder/113_articles/113_zaza_secrets_revealed.html, accessed November 11, 2008.

Figure 7.9 drawing by George E. Stuart reproduced from Terrence Kaufman and John Justeson, “Epi-Olmec hieroglyphic writing and texts” (2001). Available online at www.albany.edu/anthro/maldp/papers.htm, accessed October 15, 2008.

Figure 7.11 from Terrence Kaufman and John Justeson, “Epi-Olmec hieroglyphic writing and texts” (2001). Available online at www.albany.edu/anthro/maldp/papers.htm, accessed October 15, 2008, reprinted by permission.

Figures 8.1 and 8.2 photos excerpted from film footage by John Haviland and Steve Levinson, reproduced with permission.

Figure 8.3 p. 156 in Stephen C. Levinson, Space in Language and Cognition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), reprinted by permission of Cambridge University Press.

Figure 8.4 photos by kind permission of Daniel Haun.

Figure 8.5 p. 430 in R. Núñez and E. Sweetser, “With the future behind them: Convergent evidence from Aymara language and gesture in the crosslinguistic comparison of spatial construals of time,” Cognitive Science 30, 3, 401–50 (2006), reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor and Francis Ltd, www.tandf.co.uk/journals).

Figure 8.6 p. 436 in R. Núñez and E. Sweetser, “With the future behind them: Convergent evidence from Aymara language and gesture in the crosslinguistic comparison of spatial construals of time,” Cognitive Science 30, 3, 401–50 (2006), reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor and Francis Ltd, www.tandf.co.uk/journals).

Figures 8.7–11 frames extracted from the video files of experiments reported in Sotaro Kita and Aslı Özyürek, “What does cross-linguistic variation in semantic coordination of speech and gesture reveal? Evidence for an interface representation of spatial thinking and speaking,” pp. 16-32 from Journal of Memory and Language 48 (2003). Reproduced with permission.

Figure 8.12 from Melissa Bowerman, “The tale of ‘tight fit’: How a semantic category grew up.” PowerPoint presentation for talk at “Language and Space” workshop, Lille, May 9, 2007.

Figure 9.2 from Milman Parry Collection, Harvard University.

Figure 9.3 photo courtesy of Don Niles, Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies.

Photo in box 9.1 courtesy of Nicole Kruspe.

Figure 9.4 photo by Mary Moses, reprinted with permission of Tony Woodbury.

Photo in box 10.1 courtesy of Dave Watters.

Photo in box 10.2 courtesy of Cristina Messineo.

Figure 10.1 photo courtesy of Sarah Cutfield.

Figure 10.2 photo courtesy of John Dumbacher.

Photos in box 10.4 top photo courtesy of Mara Santos, lower photo courtesy of Vincent Carelli.

For permission to use the painting “Sweers Island” on the cover of this book, I would like to thank Mornington Island Arts & Crafts and Alcaston Gallery, as well as the Bentinck Island Artists: Sally Gabori, †May Moodoonuthi, Paula Paul, Netta Loogatha, Amy Loogatha, Dawn Naranatjil, and Ethel Thomas.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions in the above list and text, and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Prologue

No volverá tu voz a lo que el persa

Dijo en su lengua de aves y de rosas,

Cuando al ocaso, ante la luz dispersa,

Quieras decir inolvidables cosas

You will never recapture what the Persian

Said in his language woven with birds and roses,

When, in the sunset, before the light disperses,

You wish to give words to unforgettable things

(Borges 1972:116–17)1

Un vieillard qui meurt est une bibliothèque qui brûle.

An old person dying is a library burning.

(Amadou Hampaté Bâ, address to UNESCO, 1960)

Pat Gabori, Kabararrjingathi bulthuku,2 is, at the time I write these words, one of eight remaining speakers of Kayardild, the Aboriginal language of Bentinck Island, Queensland, Australia. For this old man, blind for the last four decades, the wider world entered his life late enough that he never saw how you should sit in a car. He sits cross-legged on the car seat facing backwards, as if in a dinghy. Perhaps his blindness has helped him keep more vividly alive the world he grew up in. He loves to talk for hours about sacred places on Bentinck Island, feats of hunting, intricate tribal genealogies, and feuds over women. Sometimes he interrupts his narrative to break into song. His deep knowledge of tribal law made him a key witness in a recent legal challenge to the Australian government, to obtain recognition of traditional sea rights. But fewer and fewer people can understand his stories.

Kayardild was never a large language. At its peak it probably counted no more than 150 speakers, and by the time I was introduced to Pat in 1982 there were fewer than 40 left, all middle-aged or older.

The fate of the language was sealed in the 1940s when missionaries evacuated the entire population of Bentinck Islanders from their ancestral territories, relocating them to the mission on Mornington Island, some 50 km to the northwest. At the time of their relocation the whole population were monolingual Kayardild speakers, but from that day on no new child would master the tribal language. The sibling link, by which one child passes on their language to another, was broken during the first years after the relocation, a dark decade from which no baby survived. A dormitory policy separated children from their parents for most of the day, and punished any child heard speaking an Aboriginal language.

Figure 0.1 Pat Gabori, Kabararrjingathi bulthuku (photo: Nicholas Evans)

Kayardild, which we shall learn more about in this book, challenges many tenets about what a possible human language is. A famous article on the evolution of language by psycholinguists Steve Pinker and Paul Bloom, for example, claimed that “no language uses noun affixes to express tense”3 (grammatical time). This putative restriction is in line with Noam Chomsky’s theory of Universal Grammar, which sees a prior restriction on possible human languages as an essential aid to the language- learning child in narrowing down the set of hypotheses she needs to deduce the grammar underlying her parents’ speech.

Well, Kayardild blithely disregards this supposed impossibility, and marks tense on nouns as well as verbs. If you say “he saw (the) turtle,” for example, you say niya kurrijarra bangana. You mark the past tense on the verb kurrij “to see,” as -arra, but also on the object-noun banga “turtle,” as -na. Putting this into the future, to “he will see (the) turtle,” you say niya kurriju bangawu, marking futurity on both verb (−u) and noun (−wu). (Pronounce a, i, and u with their Spanish or Italian values, the rr as a trill, the ng as in singer, and the j as in jump.)4

Kayardild shows us how dangerous it is to talk about “universals” of language on the basis of a narrow sample that ignores the true extent of the world’s linguistic diversity.5 Thinking about it objectively, the Kayardild system isn’t so crazy. Tense locates the whole event in time – the participants, as well as the action depicted by the verb. The tense logics developed by logicians in the twentieth century plug whole propositions into their tense operators, including the bits denoted by both verbs and nouns in English. Spreading around the tense-marking, Kayardild-style, shows the “propositional scope” of tense.

But learning Kayardild is not just a matter of mastering a grammar that no human language is supposed to have. It also requires you to think quite differently about the world. Try moving the eastern page of this book a bit further north on your lap. Probably you will need to do a bit of unfamiliar thinking before you can follow this instruction. But if you spoke Kayardild, most sentences you uttered would refer to the compass points in this way, and you would respond instantly and accurately to this request.

Pat Gabori is in his eighties, and the youngest fluent speakers are in their sixties. So it seems impossible that a single speaker will remain alive when, in 2042, a hundred years will mark the removal of the Kaiadilt people from Bentinck Island. In the space of a lifetime a unique and fascinating tongue will have gone from being the only language of its people, to a silent figment of the past.

Traveling five hundred miles to the northwest we reach Croker Island in Australia’s Northern Territory. There, in 2003, I attended the funeral of Charlie Wardaga, my teacher, friend, and classificatory elder brother. It was a chaotic affair. Weeks had passed between his death and the arrival of mourners, songmen, and dancers from many surrounding tribes. All this time his body lay in a wooden European-style coffin, attracting a growing number of flies in the late dry-season heat, under a traditional Aboriginal bough-shade decked with red pennants in a tradition borrowed from those wide-ranging Indonesian seafarers, the Macassans. His bereaved wife waited under the bough-shade while we all came to pay our last respects, grasping a knife lying on the coffin and slashing our heads with it to allay our grief.

Figure 0.2 Charlie Wardaga (photo: Nicholas Evans)

Later, as the men silently dug Charlie’s grave pit, the old women had to be restrained from leaping in. Then the searing, daggering traditional music gave way to Christian hymns more conducive to contemplation and acceptance. With this old man’s burial we were not just burying a tribal elder pivotal in the life and struggles of this small community. The book and volume of his brain had been the last to hold several languages of the region: Ilgar, which is the language of his own Mangalara clan, but also Garig, Manangkardi, and Marrku, as well as more widely known languages like Iwaidja and Kunwinjku. Although we had managed to transfer a small fraction of this knowledge into a more durable form before he died, as recordings and fieldnotes, our work had begun too late. When I first met him in 1994 he was already an old man suffering from increasing deafness and physical immobility, so that the job had barely begun, and the Manangkardi language, for instance, had been too far down the queue to get much attention.

For his children and other clan members, the loss of such a knowledgeable senior relative took away their last chance of learning their own language and the full tribal knowledge that it communicated: place-names that identify each stretch of beach, formulae for coaxing turtle to the surface, and the evocative lines of the Seagull song cycle, which Charlie himself had sung at other people’s funerals. For me, as a linguist, it left a host of unanswered questions. Some of these questions can still be answered for Iwaidja and Mawng, relatively “large” related languages with around two hundred speakers each. But others were crucially dependent on Ilgar or Marrku data.

My sense of despair at what gets lost when such magnificent languages fall silent – both to their own small communities and to the wider world of scholarship – prompted me to write this book. Although my own first-hand experience has mainly been with fragile languages in Aboriginal Australia, similar tragedies are devastating small speech communities right around the world. Language death has occurred throughout human history, but among the world’s six thousand or more modern tongues the pace of extinction is quickening, and we are likely to witness the loss of half of the world’s six thousand languages by the end of this century.6 On best current estimates, every two weeks, somewhere in the world, the last speaker of a fading language dies. No one’s mind will again travel the thought-paths that its ancestral speakers once blazed. No one will hear its sounds again except from a recording, and no one can go back to check a translation, or ask a new question about how the language works.

Each language has a different story to tell us. Indeed, if we record it properly, each will have its own library shelf loaded with grammars, dictionaries, botanical and zoological encyclopedias, and collections of songs and stories. But language leads a double life, shuttling between “out there” in the community of speakers and “in there” in individual minds that need to know it all in order to use and teach it. So there come moments of history when the whole accumulated edifice of an oral culture rests, invisible and inaudible, in the memory of its last living witness. This book is about everything that is lost when we bury such a person, and about what we can do to bring out as much of their knowledge as possible into a durable form that can be passed on to future generations.

Such is the distinctiveness of many of these languages that, for certain riddles of humanity, just one language holds the key. But we do not know in advance which language holds the answer to which question. And as the science of linguistics becomes more sophisticated, the questions we seek answers to are multiplying.

The task of recording the knowledge hanging on in the minds of Pat Gabori and his counterparts around the world is a formidable one. For each language, the complexity of information we need to map is comparable to that of the human genome. But, unlike the human genome, or the concrete products of human endeavor that archaeologists study, languages perish without physical trace except in the rare cases where a writing system has been developed. As discernible structures, they only exist as fleeting sounds or movements. The classic goal of a descriptive linguist is to distil this knowledge, by a combination of systematic questioning and the recording and transcribing of whatever stories the speaker wishes to tell, into at least a trilogy of grammar, texts, and a dictionary. Increasingly this is supplemented by sound and video recordings that add information about intonation, gesture, and context. Though documentary linguists now go beyond what most investigators aspired to do a hundred years ago, we can still capture just a fraction of the knowledge that any one speaker holds in their heads, and which – once the speaker population dwindles – is at risk of never coming to light because no one thinks to ask about it.

This book is about the full gamut of what we lose when languages die, about why it matters, and about what questions and techniques best shape our response to this looming collapse of human ways of knowing. These questions, I believe, can only be addressed properly if we give the study of fragile languages its rightful place in the grand narrative of human ideas and the forgotten histories of peoples who walked lightly through the world, without consigning their words to stone or parchment. And because we can only meet this challenge through a concerted effort by linguists, the communities themselves, and the lay public, I have tried to write this book in a way that speaks to all these types of reader.

Revolutions in digital technology mean that linguists can now record and analyze more than they ever could, in exquisitely accurate sound and video, and archive these in ways that were unthinkable a generation ago. At the same time, the history of the field shows us that good linguistic description depends as much on the big questions that linguists are asking as it does on the techniques that they bring to their field site.

Tweaking an old axiom, you only hear what you listen for, and you only listen for what you are wondering about. The goal of this book is to take stock of what we should be wondering about as we listen to the dying words of the thousands of languages falling silent around us, across the totality of what Mike Krauss has christened the “logosphere”: just as the “biosphere” is the totality of all species of life and all ecological links on earth, the logosphere is the whole vast realm of the world’s words, the languages that they build, and the links between them.

Further Reading

Important books covering the topic of language death include Grenoble and Whaley (1998), Crystal (2000), Nettle and Romaine (2000), Dalby (2003), and Harrison (2007); for a French view, see Hagège (2000).

The difficult challenge of what small communities can do to maintain their languages is a topic I decided not to tackle in this book, partly because there were already so many other topics I wanted to cover, but also because it is such an uphill battle, with so few positive achievements, and as much at the mercy of political and economic factors as of purely linguistic ones. Good general accounts of the problem can be found in Bradley and Bradley (2002), Crystal (2000), Hinton and Hale (2001), Grenoble and Whaley (2006), Tsunoda (2005). See also Fellman (1973) for an account of the successful revival of Hebrew pioneered by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, and Amery (2000) for an upbeat account of the attempts by the Kaurna people of South Australia to revive their language.

A Note on the Presentation of Linguistic Material

One of the themes of this book is that each language contains its own unique set of clues to some of the mysteries of human existence. At the same time, the only way to weave these disparate threads together into a unifying pattern is on the loom of a common language, which in this book is English.

The paradox we face, as writers and readers about other languages, is to give a faithful representation of what we are studying in all its particularity, and at the same time to make it comprehensible to all who speak our language.

The first problem is how to represent unfamiliar sounds. Do we adapt the English alphabet, Berlitz-style, or do we use the technical phonetic symbols that, with their six hundred or so letter-shapes, are capable of accurately representing each known human speech sound to the trained reader? Thus we can use either English ng or the special phonetic symbol ŋ to write the sound in the Kayardild word “turtle” (a: represents a long a, so the whole word is pronounced something like bung-ah in English spelling conventions). Or we can write the Kayardild word for “left” as thaku, adapting English letters, but we then need to remember that the initial th, although it involves putting the tongue between the teeth like in English, is a stop rather than a fricative. It sounds like the d in width or the t in eighth – try watching your tongue in the mirror as you say these – and can be represented accurately by the special phonetic symbol , where the little diacritic shows that the tongue is placed between the teeth: thus, .

Since so many of the languages we will look at have sounds not easily rendered in English, I will sometimes need to use special phonetic symbols, which are spice to the linguist but indigestible to the lay reader. If you are in this latter category, just ignore the phonetic representation. When the point I am making depends on the pronunciation I will give a Berlitz-style rendition, but when it does not you should just work from the gloss and the English translation. Note also that, since some minority languages have developed their own practical orthographies (spelling systems), it is often more appropriate to write words in these rather than in standardized phonetic symbols.

There is a second problem, perhaps a deeper one, as it engages with the inner concepts of the language, not just the outer garment of its pronunciation: how do we show the often unfamiliar packaging of its concepts? In the technical style of linguistics articles we have a solution to this: a traditional three-line treatment that transcribes each language phonetically on one line, then gives an interlinear gloss (or just gloss) breaking it down into its smallest meaningful parts, then a free translation into English.

Consider the problem of representing what Pat Gabori said in a Native Title hearing when he was asked to take an oath equivalent to “I shall tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.” I was interpreting in that hearing, and Pat and I had to confer for a while before he came up with the following formulation, which I will show the way that linguists would write it:

(1) Ngada maarra junku-ru-thu,

I only right-FACTITIVE-POTENTIAL

thaku-ru-nangku.

left-FACTITIVE-NEGATIVE.POTENTIAL

Literally: “I will only make things right, I won’t make (anything) left.”

Freely: “I will only make things correct, I won’t twist or distort anything.”

As you can see, the Kayardild version compresses two English sentences into just four words. Additionally, it uses a symmetrical metaphor (right → correct :: left → incorrect) where English only extends one of the terms (right) into the domain of truth and correctness. Setting the sentence out as in (1), by showing the word roots, makes this clear. Additionally, Kayardild can build new “factitive” verbs from adjectives, with the general meaning “to make, cause [some state X],” by adding a word-building (or “derivational”) suffix -ru. We could, of course, just treat junkuru- as a unit meaning “make correct” and thakuru- as a unit meaning “make wrong, twist, garble,” but then you would lose the logic of how the words are built up. And, finally, Kayardild verbs choose from a large set of suffixes that show tense (when) and polarity (affirmative vs. negative): -thu means “will,” while -nangku means “won’t.” They are glossed here as POTENTIAL and NEGATIVE.POTENTIAL.

You might ask why we do not simply translate -ru- as “make” and -thu as “will”? Well, there is a good reason not to do this: the translation would be rough and inaccurate. This is because -thu can also mean “can, may, should” – hence the gloss “potential” which aims to capture what is common in these meanings through a more abstract term. Likewise, -ru- does not correspond specially well with “make” since it only combines with words denoting states: to say “I made him come down/descend” I would take the word thulatha “descend, come down” and add a different suffix, -(a)rrmatha, giving thulathar-rmatha. This second suffix is used when causing an action rather than a state.

This method of interlinear glossing, then, allows us to show faithfully how words sound in the original language, translate them as well as possible into the language I am using to you, and at the same time display the grammatical structure of the original with as little distortion as possible. In general I will use this method to display examples, but in the interests of broader readability sometimes I will change the glosses of the original sources to make them more accessible without betraying the main point of the example.

In addition to the linguistic examples, I have had to decide what to do with the various quotes that pepper this book, from many languages and cultural traditions. In a book on the fragility of languages, this is not out of obscurity. A major cause of language loss is the belief that everything wise and important can be, and has been, said in English. Conversely, it is a great stimulant to the study of other languages to see what they express so succinctly. So in general I have put such quotes first in their original language, followed by a translation (my own unless otherwise indicated). I hope the slightly greater effort this entails for you, the reader, will be rewarded by the treasures you will go on to discover.

Most languages mentioned in the book can be located from at least one map, except for (a) national languages whose location is well-known or deducible from the nation’s location, (b) ancient languages whose location is not known precisely, (c) scripts. If there is no explicit mention of the language’s location in the text, use the index at the back of the book to locate a relevant map.

Part I

The Library of Babel

Tuhan, jangan kurangi

sedikit pun adat kami.

Oh God, do not trim

a single custom from us.

(Indonesian proverb)

Oh dear white children, casual as birds,

Playing among the ruined languages,

So small beside their large confusing words

So gay against the greater silences …

(Auden 1966)

In the biblical myth of the Tower of Babel, humans are punished by God for their arrogance in trying to build a tower that would reach heaven. Condemned to speak a babble of mutually incomprehensible languages, they are quarantined from each other’s minds. The many languages spoken on this earth have often seemed a curse to rulers, media magnates, and the person in the street. Some economists have even implicated it as a major cause of corruption and instability in modern nations.1

The benefits of communicating in a common idiom have led, in many times and places, to campaigns to spread one or another metropolitan standard – Latin in the Roman Empire, French in Napoleonic France, and Mandarin in today’s China. Sometimes these are promoted by governments, but increasingly media organizations, aided by satellite TV, are doing the same: arguably Rupert Murdoch’s Star Channel is doing more to spread Hindi into remote Indian villages than 60 years of educational campaigning by the Indian government. We live today with an accelerating tempo of language spread for a few world languages – English, Chinese, Spanish, Hindi, Arabic, Portuguese, French, Russian, Indonesian, Swahili. Another couple of dozen national languages are expanding their speaker bases toward an asymptote where all citizens of their countries speak the one language; at the same time they are giving ground themselves in terms of higher education and technological literature to English and the other world languages. Humankind is regrouping, away from their Babel, some millennia after sustaining their biblical curse.

But many other cultures have regarded language diversity as a boon. In chapter 1 we shall begin by examining some alternative founding myths, widespread in small-scale cultures, that give very positive reasons for why so many languages are spoken on this earth. For the moment, though, let’s stick with the Babel version, but with the twist given to it by Jorge Luis Borges. His fabulous Library of Babel contains all possible books written in all possible languages, subject to a limit of 410 pages per tome. It thus contains all possible things sayable about the world, including all that scientists, philosophers, poets, and novelists might express – plus every possible falsehood and piece of uninterpretable nonsense as well. (We can extend his vision a bit by clarifying that all possible writing systems are allowed – Ethiopic, Chinese, phonetic script, written transcriptions of sign languages … )

For Borges, the Library of Babel was an apt metaphor because it allowed us to conceive of a near-infinity of stories and ideas by increasing the number of languages they were written in, each idiom stamping its great masterpieces with the rhythm and take of a different world-view – Cervantes alongside Shakespeare, the Divine Comedy alongside the Popol Vuh, Lady Murasaki alongside Dostoyevsky, the Rig Veda alongside the Koran. (We can of course expand his idea to include stories told or chanted in the countless oral cultures of the world and that have yet to be written down – a topic we return to in chapter 9.) As English, Spanish, Mandarin, and Hindi displace thousands of tiny languages in the hearths of small communities, much of this library is now molding away.

Our library will also contain grammars and dictionaries – of the six thousand or so languages spoken now, plus all that have grown and died since humans began to speak. (Of course most of these grammars and dictionaries have still not been written, and those from vanished past languages never can be, but remember that Borges’ Library contains all possible books alongside its actual ones!) In this linguistic reference section of the library we can read how, in the words of George Steiner, every language “casts over the sea its own particular net, and with this net it draws to itself riches, depths of insight, and lifeforms which would otherwise remain unrealized.”2 When we browse our way into this wing, we are looking not so much at what is written in or told in the languages – but what has been spoken into them. By this I mean that speakers, in their quest for clarity and vividness, actually create new grammars and new words over time. Ludwig Wittgenstein once offered his famous advice Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen – “whereof you cannot speak, thereof must you remain silent.” Fortunately millennia of his predecessors ignored this injunction, in the process forging the languages that we use to communicate today. Untold generations, through their attempts to persuade and to explain, to move and to court, to trick and to exclude, have unwittingly built the vast, intricate edifices that collectively represent humankind’s most fundamental achievement, since without it none of the others could be begun. The contents of this wing of the library are also teetering in disrepair.

In this section of the book we broach two topics. In chapter 1 we take stock of the astonishing linguistic diversity that still exists in those parts of the Library of Babel that are still standing, however rickety. We ask where in the world this diversity is found, how it has come to be, and what it means. In chapter 2 we examine the millennially slow dawning of interest in what these languages have to tell us, an indifference that has left huge and aching gaps in what we know about many past and present peoples of the world. By knowing what our predecessors were deaf to, we will be better prepared to open our ears to the many questions we will be raising in the rest of the book.

1

Warramurrungunji’s Children

Oh Mankind, we have created you male and female, and have made you into nations and tribes that ye may know one another

(Koran 49:13, Pickthal translation)

In the oral traditions of northwestern Arnhem Land, the first human to enter the Australian continent was a woman, Warramurrungunji, who came out of the Arafura Sea on Croker Island near the Cobourg Peninsula, having traveled from Macassar in Indonesia. (Her rather formidable name is pronounced, roughly: worra-moorrooo-ngoon-gee [wóramùruŋùi].) Her first job was to sort out the right rituals so that the many children she gave birth to along the way could survive. The hot mounds of sand, over which she and all women thereafter would have to purify themselves after childbirth, remain in the landscape as the giant sandhills along Croker Island’s northern coasts. Then she headed inland, and as she went she put different children into particular areas, decreeing which languages should be spoken where. Ruka kundangani riki angbaldaharrama! Ruka nuyi nuwung inyman! “I am putting you here, this is the language you should talk! This is your language!” she would say, in the Iwaidja version of the story, naming a different language for each group and moving on.

Figure 1.1 Tim Mamitba telling the Warramurrungunji story (photo: Nick Evans)

Language Diversity and Human Destiny

ŋari-waidbaidjun junbalal-ŋuban wuldjamin daa-walwaljun lilia-woŋaSpeech of different clans, mingling together…duandja mada-gulgdun-maraŋala dualgindiuDua moiety clans, with their special distinct tongues.wulgandarawiŋoi murunuŋdu jujululwiŋoi garaŋariwiŋoi garidjalulu mada-gulgdun-maraŋalaPeople from Blue Mud Bay, clans of different tongues talking together…buduruna ŋari-waidbaidjun woŋa ŋari-ŋariunWords flying over the country, like the voices of birds…(Song 2, Rose River Cycle, Berndt 1976:86–7, 197–8)

The Judeo-Christian tradition sees the profusion of tongues after the Tower of Babel as a negative outcome punishing humans for their presumption, and standing in the way of cooperation and progress. But the Warramurrungunji myth reflects a point of view much more common in small speech communities: that having many languages is a good thing because it shows where each person belongs. Laycock quotes a man from the Sepik region of Papua New Guinea saying “it wouldn’t be any good if we all talked the same; we like to know where people come from.”1 The Tzotzil oral traditions of the Mexican Chiapas give another twist to this tune: “while the sun was still walking on the earth, people finally learned to speak (Spanish), and all people everywhere understood each other. Later the nations and municipios were divided because they had begun to quarrel. Language was changed so that people would learn to live together peacefully in smaller groups.”2

I recently drove down the dusty road from Wilyi on the coast near Croker Island, to the inland town of Jabiru (figure 1.2), while working with speakers of Iwaidja, the language in which Tim Mamitba (figure 1.1) had told me the Warramurrungunji story. The 200-kilometer transect follows Warramurrungunji’s path, traveling inland and southwards from beach through eucalyptus savannah, stretches of tropical wetlands and lily ponds, and occasional sandstone outcrops whose caves hold vast galleries of rock paintings. It is a timeless landscape rich in wild food – magpie geese, fish, bush fruits, and yams. Its Aboriginal inhabitants can live easily through the year, finding all they need on their own clan countries. The few river crossings do not present geographical barriers. But Warramurrungunji’s legacy of linguistic diversity is clearly here. In a few hours on the road we passed through the territories of nine clans and seven languages from four language families, at least as different from each other as Germanic, Slavic, Indo-Aryan and Romance (see table 1.1).

To give a rough idea of how different the languages are at the two ends of this transect, consider the useful sentence “you eat fish.” Taking Iwaidja from one end, and Gun-djeihmi from the other, we compare kunyarrun yab and yihngun djenj – of which only the final -n in the two languages, which marks non-past tense in both, is historically relatable. Imagine I had driven from London to Moscow – 15 times as far. The Russian equivalent ty esh rybku, although incomprehensible to English ears, contains three cognate elements, at least if we cheat a bit by taking the earlier English version thou eatest fish: ty (with English thou), e (with English eat) and -sh (with the older English suffix -est in eatest). And if I satisfy myself with a shorter trip to Berlin – still more than five times the Wilyi-Jabiru trip – we get the almost comprehensible du ißt (isst) Fisch, in which every element is cognate.

Figure 1.2 Clans and languages in northwestern Arnhem Land

Some of these languages are now down to just a couple of speakers (Amurdak) or have recently ceased to be spoken (Manangkardi), but others are still being learned by children. Bininj Gun-wok, the largest, now has about 1,600 first-language speakers as members of other groups shift to it. But the average population per language in this region is much smaller, probably less than 500 speakers. And many are even smaller: a recent study by Rebecca Green4 on Gurr-goni, a few hundred kilometers to the east of the Warramurrungunji track, suggests it has been quite stable for as long as anyone remembers, never with more than around 70 speakers.

Table 1.1 Clans and languages along the 200-kilometer track from Wilyi to Jabiru3

ClanLanguageLanguage familyMurranIwaidjaIwaidjan; IwaidjicManangkaliAmurdakIwaidjan; SouthernMinakaManangkardiIwaidjan; IwaidjicBorn/Kardbam (Alarrju)Bininj Gun-wok (Kunwinjku dialect)Gunwinyguan (Central)MandjurlngunBininj Gun-wok (Kunwinjku dialect)Gunwinyguan (Central)BunidjGaagudjuGaagudjuan (Isolate)Mandjurlngun MengerrMengerrdjiGiimbiyuManilakarrUrningangkGiimbiyuBunidj Gun-djeihmi,Bininj Gun-wokGunwinyguan (Central)Mirarr Gun-djeihmi(Gun-djeihmi dialect)Each person from this region has one “father language,” which they have special rights in, by virtue of the clan membership they get from their father. This vests them with authority and spiritual security as they travel through their ancestral lands. In traveling to places that have not been visited for some time, clan members should call out to the spirits in the local language, to show they belong to the country. Doing this with visitors is the duty and right of a host. It is said that many resources, such as springs, can only be accessed if you address them in the local idiom. For these reasons there are intimate emotional and spiritual links between language and country. Travelers sing songs listing the names of sites as they move through the land, and switch languages as they cross creeks and other clan boundaries. In epics of ancestral travels it is common to flag where the characters have got to simply by switching the language the story is told in – as if the Odyssey were told not just in Greek, but in the half a dozen ancient Mediterranean languages Ulysses would have encountered in his travels.

Throughout Aboriginal Australia, speaking the appropriate local language is a kind of passport, marking you – both to local people and to the spirits of the land – as someone known and familiar, with the right to be there. I once went out in a boat with Pat Gabori to map a Kayardild site a few kilometers off shore, in the company of several Kayardildtalkative senior women and a few children who did not know their ancestral language. Pat and the women called out in Kayardild to the spirits and ancestors of the place, identifying themselves and introducing the silent children, and explaining gently that the children’s inability to speak Kayardild did not make them strangers – they just hadn’t learned the language yet.

A more extreme illustration of this principle comes from a story Pluto Bentinck, another old Kayardild man, related during a Native Title claim. When asked if traditional law included sanctions to be taken against trespassers, he cited an incident during World War II, when a hapless white airman swam ashore on Bentinck Island after his plane crashed in the sea. Pluto told me the man had said danda ngijinda dulk, ngada warngiida kangka kamburij (“this is my country, I just speak this one language”), as he struggled ashore without his Berlitz Kayardild phrasebook. When I asked him how he knew what the man had said, when he himself knew no English, Pluto replied: Marralwarri dangkaa, ngumbanji kangki kamburij! (“He was an ear-less (crazy) man, he spoke your language!”). Speaking English on Bentinck Island, in Pluto’s view, was tantamount to claiming it for English speakers. Nyingka kabatha birdiya kangki! Ngada yulkaanda mirraya kangki kabath! he had replied to the man (“You found the wrong words! I’ve found the right words, since forever”). Ngada bunjiya balath, karwanguni, Pluto continued: “And I clubbed him in the back of the neck”.5

Normal members of Arnhem Land society are highly multilingual, often speaking half a dozen languages by the time they are adults. This is helped by the fact that you have to marry outside your clan, which likely means your wife or husband speaks a different language from you. It also means that your parents each speak a different language, and your grandparents three or four languages between them. The late Charlie Wardaga, my Ilgar teacher, was typical. Knowledge of Ilgar, Manangkardi, Marrku, Iwaidja, and Kunwinjku came to him from his grandparents and parents. Although he lived mostly on lands where Ilgar, Marrku, and Iwaidja were the locally appropriate languages, he married a Kunwinjku-speaking woman from a mainland clan and would regularly speak Kunwinjku with her and her relatives, or when traveling to distant communities as a songman. In this system your clan language is your title deed, establishing your claims to your own country, your spiritual safety and luck in the hunt there. Meanwhile the knowledge of other languages gives you the far-flung network of relatives, spouses actual and potential, ceremonial age-mates and allies, which makes you someone who counts in the greater world. This combination of highly developed multilingualism with strong attachments to small local languages is by no means an Arnhem Land oddity – around the world, it is common in zones of high linguistic diversity, like Nagaland in northeastern India, or the Mandara Mountains of Cameroon (see box 1.1).