15,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Merlin Unwin Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

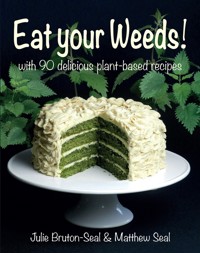

Why should we eat our weeds? Because they are delicious, they're nutritious, they're too good to waste. And they're free! This is more than just a recipe book, more than a foraging book. Professional herbalist and best-selling author Julie Bruton-Seal and Matthew Seal have both shared their expertise in Eat your Weeds! to give us the fascinating background to these overlooked wild plants, their historic uses, their medicinal benefits today and their culinary delights. Weeds are amazing beings that we have failed to see and failed to eat. But with these 90 delicious plant-based recipes, that is about to end.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

2

Jack by the hedge wraps, p160

3

Contents

6

If I should set downe all the sorts of herbes that are vsually gathered for Sallets, I should not onely speake of Garden herbes, but of many herbes, &c. that growe wilde in the fields, or else be but weedes in a Garden. – John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole (1629)

Preface and Acknowledgements

This book is a celebration of weeds, the resilient wild plants that have learned to live alongside humans and travel the world with them. These are companions of our backyard and probably yours too, though you may not have thought of them before now as sources of delicious food.

The title and full idea for the book arrived in a dream of Julie’s in October 2019, and we began work. We have long admired the strengths and virtues of our common weeds, and wanted to get to know them better. After much thought, we chose 23 plants and a mushroom that are widespread in Britain but also in the wider temperate world, and which we found tasty to eat in various forms. We also wanted to offer in-depth plant biographies to accompany the recipes, giving some idea of how certain weeds have been so successful.

Weeds are hated by gardeners, especially ground elder and honey mushroom, and in practice are almost impossible to get rid of. If you are stuck with these tenacious life forms, perhaps it’s time to appreciate their good side – if you can’t beat them, eat them!

Weeds are defined as plants in the wrong place, as outcasts, not welcome in our fields and gardens. But consider, there is no botanical family called weeds; a weed is a purely human construct. They are subject to our ‘plant blindness’, being too much under our noses to have been thought useful at all, while we look to exotic plants from far away. If we notice weeds at all, it is as enemies – they are in our way, whether farmer or gardener, and we are out to destroy them, always destroy.

It’s a mindset that we think needs to change. We propose that weeds can be a useful free food resource, a garden microcrop. They can and should be a delicious, local and sustainable addition to our everyday cuisine, offering us exciting new flavours. They are there as survival food if we need it, and grow happily without any help from us.

Like every project this one has deeper roots too. Julie has been co-author of a plant-based recipe book before, working with her friend Carol Tracy in the 1980s on Vegetarian Masterpieces. Self-published in spiral-bound format in Charlotte NC, it went into at least ten printings.

Matthew has another route into the present book. He remembers his father, George Seal, buying Sir Edward Salisbury’s Weeds & Aliens book in the New Naturalist series, when it appeared in 1961, for the then hefty price of 30 shillings (closer to £30 today).

The book itself revealed somebody taking weeds seriously and doing amazing research on plants that were usually dismissed, not discussed. Somewhere along the line Matthew ‘acquired’ the book, and it has been a background resource in the present project.

All of our previous five books together have featured recipes, whether ‘receipts’ in the old sense of herbal preparations or the modern notion of instructions for cooking food. The present book is really an extension of our recipe-making rather than a departure, with the subject matter now domestic weeds and the food recipes specifically plant-based.

Recipes can seldom be wholly original but we have taken inspiration from cuisines worldwide, and have tried to give a wide variety of ways to enjoy our chosen weeds. We hope readers will be inspired to embark on careful culinary experiments with their own local weed flora.

We have trialled all the recipes for ourselves, the process of collecting, cooking and photographing them testing – and rewarding – our patience and hunger pangs.

We have had enthusiastic support from friends, family and colleagues in tasting our food or our words. We particularly thank Jen Bartlett, Andrew Chevallier, Kaz da Silva, Maria Davidson, Charlotte du Cann, Mark Fairhead, Christina Gathergood, Fred Gillam, Christine Herbert, Valerie Macfarlane, Anne Roy, Helen Seal, Ruby Taylor and Monica Wilde. Needless to say, we alone take full responsibility for the contents.

All the photographs are by Julie, except for the author photo taken by Tarl Bruton. We thank the John Innes Foundation Collection of Rare Botanical Books, Norwich, for permission to reproduce the image of plantain by Maria Merian (1717).

Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal Ashwellthorpe, Norfolk, January 2022

8

Introduction

The same wild integrity that exists in plants growing in pristine wilderness areas is also found in the nature of the wild weeds growing in open lands around and in the margins of civilization. Wild weeds have an intrinsic wisdom for resilience and have mastered their abilities of survival. – Blair (2014)

Mowing the grass once a fortnight in pleasure grounds, as now practised, is a costly mistake. We want shaven carpets of grass here and there, but what nonsense it is to shave it as often as foolish men shave their faces! … Who would not rather see the waving grass with countless flowers than a close surface without a blossom? – Robinson (1895)

There is a sort of sacredness about them [weeds]. Perhaps if we could penetrate Nature’s secrets we should find that what we call weeds are more essential to the well-being of the world than the most precious fruit or grain. – Hawthorne (1869)

It would appear that at the moment many plants are beginning to speak up for themselves and call our attention to the fact that we have been completely ignoring them as weeds, or as rather insignificant local, outdated beings that have been superseded by the exotic exciting new favourites, often from overseas, often packaged as products. – Darrell (2020)

[there remains] a creeping garden beneath us, seeking an opportunity to flourish in the cracks of things we build. – Rees (2019)

The most important flowers in the world are not those Wordsworth saw – that sea of golden daffodils. It’s the one dandelion at the bus stop, the one brave soul poking out of the concrete. It’s the pure, simple beauty of nature, like the blackbird’s song. – Packham (2021)

As you learn and forage new plants it is important (and fun) to take the time to experiment with them. … Plantain can be turned into ‘seaweed’ … stinging nettles are beautiful and crunchy once fried and sprinkled with wild spices … curly dock leaves can become sushi wraps. … I tell my students that they don’t have to think outside of the box but can simply eliminate the box altogether! Think freely! Many edible foraged plants have culinary uses that are begging to be discovered. – Baudar (2016)

Why should we eat our weeds? Because they are delicious, adding a palate of new flavours in everyday cooking. They are also nutritious and too good to waste.

Weeds are actually more nutritious than most of the vegetables we grow or buy. They often have deep roots that loosen the soil and bring minerals up from far below. Weeds can help cover the soil, keep moisture in it and preserve its fertility.

They offer a second crop among our other plants, for free, and are often available in the late winter and early spring when our vegetables are yet to get going. When it’s time to weed, the edible weeds can be eaten. Why throw perfectly good food on the compost heap?

Weeds are strong and resilient, and can survive the vagaries of climate change better than our pampered crops. We now know that a greater diversity of plants enhances life in the soil, which in turn makes the soil more fertile and more able to hold water and to sequester greenhouse gases. Healthier soil means healthier food and healthier people.

Plants have been growing on Earth for millions of years, while we as humans are very recent arrivals. Weeds are the plants that have best adapted to our presence and activities, particularly since we adopted agriculture about 10,000 years ago. They have been our constant companions, but our relationship with them has usually been toxic and destructive.

Weeds are amazing beings that we have failed to see.

Weeds and weedness

Please don’t dismiss weeds as weedy. ‘Weedy’ or ‘weediness’ imply something weak, spindly, rather useless. In fact weeds are exactly the opposite.

People used to think that cleavers, for example, was weak because it draped itself over other vegetation. Scientists now say its stems have the highest breaking strains yet recorded in a land-based plant, and it has complex differential upper and lower spinal arrays, allowing it to cling or release as needed.

Since ‘weediness’ is no longer a useful term we propose using weedness to describe the many features of weeds that make them so capable of survival. For instance, we identify seventeen measures of weedness for blackberry, king of weeds in our garden.

We invite you to see weeds in another light, to see them at all in fact.

We moderns do suffer plant blindness, and it’s a matter of re-education – weeducation, we’d say, tongue in cheek – to recover a form of seeing that we have lost. Gardeners are more likely than the general population to notice plants, but many weeds only make them ‘see red’ and think murderous thoughts.

We appreciate it is a big ‘ask’ to look at weeds as having any positive value, let alone eat them, but we think the effort will repay you. Others have made the same journey.

‘I will stop to notice thee’

The English poet John Clare (1793–1864) had deep weed (in)sight. He was a farm labourer, a ‘weeder’ in his own words, and he loved ‘all wild flowers (none are weeds with me)’ – for biography, see Bate 2004.

Clare’s poem ‘To an Insignificant Flower, obscurely blooming in a lonely wild’ (1820) begins

And though thou seem’st a weedling wild,

Wild and neglected like me,

Thou still art dear to Nature’s child,

And I will stop to notice thee.

First is stopping and noticing ‘an insignificant flower’. Then comes the belief that a humble weed can be the match of any garden flower:

For oft, like thee, in wild retreat,

Array’d in humble garb like thee,

There’s many a seeming weed proves sweet,

As sweet as garden-flowers can be.

Then empathy can grow. Without ‘improvement’ (cultivation), the ‘seeming’ weed is ‘wild and neglected like me’, he writes:

And, like to thee, each seeming weed

Flowers unregarded; like to thee,

Without improvement, runs to seed,

Wild and neglected like me.

Clare could just about hold together (at least in the first part of his life) his daily toil of hoeing weeds while taking time to name, versify and appreciate them.10

Daisies and speedwell flowering in a spring lawn

Identify & destroy?

What of us two centuries on? Ever since humans began manipulating the environment for our own ends, we have been editing out the plants that aren’t useful to us. Over time we came to see weeds as competition for the plants we wanted to grow. We now know that plant relationships are far more complex than that, with soil life, particularly fungal networks, connecting everything in an entangled web of interactions.

In modern-day chemicalised agriculture, weeds in mono-crops are often exterminated with herbicides. Gardeners also use chemicals to keep things tidy. The problem is that glyphosate (Roundup®), one of the most widely used weed killers, wipes out soil micro-organisms and damages our own vital microbiome.

We aren’t saying weeds should be left to take over the world, but believe that a better balance can be reached. If you are a gardener with an abundance of ground elder, you are never likely to be able to eradicate it, so why not live with it and learn to appreciate it by using it for food, medicine and flower arrangements?

We believe a lawn full of dandelions, daisies, plantain, yarrow and other plants is far more useful and interesting than a mown green grass monoculture.

Within the balance you draw for yourself we hope you can find a space to recognise your weeds and have an ongoing relationship that includes eating them and ingesting their powerful zest for life. Indeed, all green plants are embodied light.

Weeds are free, local and sustainable, and they grow, an unused, unseen resource, without us needing to do a thing.

Identify & harvest

With weeds, as with all wild plants you may be planning to eat, proper ID is essential. Rule number one is eat only what you are sure of.

We have provided clear photographs and other written identification details for all the weeds in this book. If you are unfamiliar with these plants you may also wish to have a field guide.

In the UK, try, for example, the photographic floras of Simon Harrap (2013) or Roger Phillips (1986), or the floral paintings of Marjorie Blamey (2003) – see References at the back of the book – or many another. Wherever you live you can find local equivalents.

Best of all, locate a teacher who can introduce you to any unfamiliar plants. Take any opportunity you can to go on herb walks. Contact a herbalist or forager local to you, by word of mouth or (in the UK) check listings with the Association of Foragers. If you take your children on plant walks you could be giving them a gift for life.

If you see a plant often enough, and get close to it, touching and smelling, and best of all drawing it and sitting with it, you begin to know the way it 11carries itself, its form. In other words, you learn and intuit what the birders call ‘jizz’. Once knowing your plant’s jizz you can even recognise it from the car as it flashes by in the hedgerow (be careful, though, such botanising could become a dangerous habit!).

Remember that when digging up a plant, including a weed, if it is not on your land you need permission. In practice people might be happy for you to collect their weeds – they might even pay you to weed for them!

We give guidance on gathering/harvesting in each chapter but heed the general point to avoid plants that might have been treated with pesticides or other chemicals, or those close by the road. Of course, if picking weeds from your own garden, as we have done, you will already know whether they are organic and clean.

Weedness & bitterness

As part of becoming co-workers with your weeds we thought it useful to offer you extensive biographies of the weed subjects we have chosen. A plant like nipplewort, say, makes for wonderful eating but is relatively little known or appreciated.

Winter weeds: gathered abundance in our garden on a mild day in January

So in each of our 22 main chapters we begin with a section on weedness (‘what kind of a weed is …?’), followed by other sections related to history, uses, and gathering and cooking.

The weeds we have selected are the ones that grow around us, and that we like to eat. There are many more edible weeds in Britain and around the world, but most of the plants we have featured are worldwide weeds, found extensively in temperate regions.

Rebel botanical chalkers

France has taken a lead in banning herbicide and pesticide uses in public places (2017), and extended the ban to private gardens (2019). An unexpected outcome of these initiatives is a rising number of ‘rebel botanists’ internationally who delight in chalking the common names of weeds and pavement plants right alongside them. They then share the images on social media.

Hooray! A new visibility for the downtrodden and ignored flora of our streets. In London a French botanist, Sophie Leguil, has set up a More Than Weeds campaign and has secured the council’s permission to chalk the names of wild plants on the pavements of Hackney.

Usually this is illegal. Chalking on the pavement for hopscotch or naming weeds can land you with a fine of up to £2,500. Just let them try, we say! Meanwhile, as Leguil points out, ‘We talk a lot about plant blindness – what if putting names on plants could make people look at them in a different way? … I despair at how sanitised London has become.’

Source: Alex Morss, Guardian, 1 May 2020; updates in morethanweeds.co.uk, Le plan Ecophto II+, ecologie.gouv.fr.

Weeds, like other wild plants, will often have stronger flavours than we are 12used to. Most modern vegetables have been bred to taste more bland than their wild ancestors. This is particularly true of bitter flavours. Bitterness is a virtue in our book(s), as it was in ancient Japan, where sansai was the term used for ‘mountain vegetables’ or foraged wild plants.

Matthew practising what he preaches: rather gingerly picking nettles in Iceland

Bitterness as a taste is linked to good liver health, and bitter flavours stimulate digestion. Persist, and your taste buds will soon adapt and learn to welcome any extra bitterness that your weed meals give you.

We actually know very little of the chemistry of the plants we eat. Yes, there is data about the proteins, carbohydrates, fats and a few vitamins and minerals, and we generally have some idea of the calories certain foods provide. But plants and fungi (and their bacterial companions) produce a vast array of other compounds that contribute to their nutritional value and are vital for good health.

Overall, weeds and wild foods are nutritionally dense, which means you will need to eat less of them to feel sated. Stick with these wild tastes because you are taking in the plant’s wildness, its survival strength.

Be aware that weeds can vary in their flavours from one place or terroir to another, and at different times of year. Experiment with this diversity.

A note on presentation

We have our own style of presenting recipes, integrating ingredients and instructions into running sentences. We highlight ingredients in bold type. We feel this method is closer to how cooking actually takes place. A few cookbooks adopt this same style, and we find it much easier than having to go back and forth between a list of ingredients and the instructions.

We have taken inspiration from around the world for our plant-based recipes, and have tried to include a wide variety, both savoury and sweet, for food and drink, snacks or main meals.

Our recipes are generally quite simple, but they can be adapted and amended to suit your own preferences. Many can be used with other edible weeds than the ones we have chosen, and we encourage you to improvise once you learn to identify them confidently.

Get to know each plant through the seasons, and use your imagination to concoct your own recipes.

The old definition of weeds is that they are plants growing in the wrong place, from a human point of view. We are saying they are actually in just the right place, in our garden, for us to harvest.

We hope this book will inspire you to look at weeds with new eyes, as free ingredients for a venture into culinary ecology, as well as appreciate them for their own sake.

Measurements

We have given both metric and US cup measurements. The cups are standard measuring cups, with dry ingredients being measured level. The exact size of your measuring cup (US or UK) doesn’t matter as long as you use it consistently – it is the proportions that matter.

Eat your Weeds!

Yellow carrot, radish and Jack by the hedge salad

Alexanders

Alexanders (Smyrnium olusatrum) is a tall biennial (two-year lifespan) member of the Apiaceae (carrot family). Historically, it spread from the Mediterranean and made the switch from wild-gathered plant to garden crop, and back to wild. It was both food and medicine in Classical and medieval times. Losing out to celery as a salad crop from the 16th century, it is making a comeback as a winter-foraged wild food. The best eating is when leaves and buds are young and tender; the inner stem and roots can be braised or sautéed.

Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) Carrot family

Biennial. Dies back completely in summer, and reappears in autumn with lush light green growth.

Edible parts: Young leaves in winter; buds, flowers, stems and roots in spring; seeds in late summer.

Distinguishing features: Smooth shiny three-lobed leaves; smooth, hairless and hollow flower stalk; grows to over 1m (3.3ft), with umbels of small yellow flowers appearing in spring, followed by large seeds, which ripen to black. Smells of lovage or celery.

It’s important to know your ID in the carrot family, because there are poisonous members. The clinching factor for alexanders is that it is one of just three common yellow-flowered Apiaceae, the others being wild fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) and wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa). And it is lush and green through winter and early spring when most plants are dormant.

Caution: Avoid large quantities during pregnancy

Its certain aromatic or pungent flavour … would be too strong for modern tastes. – Pratt (1866)

… a timely potherb. – Lawson (1618)

[broth of alexanders] … which although it be a little bitter, yet it is both wholsome, and pleasing to a great many, by reason of the aromaticall or spicie taste, warming and comforting the stomack, and helping it digest the many waterish and flegmaticke meates [that] are in those times [spring] much eaten. – Parkinson (1629)

What kind of a weed is alexanders?

Geoffrey Grigson, writing in 1955, says alexanders is happiest and most frequent by the sea. He’s right, and sturdy stands of this vigorous and stately umbellifer proliferate in sheltered cliff and roadsides near eastern and southern coasts of Britain and Ireland, often on small islands. It is a scarce coastal species in parts of North America.

It also seems to be pressing inland, at least in our part of East Anglia, thriving in hedgerows some 55km (35 miles) from the Norfolk coast, and in gardens. The picture opposite shows alexanders by our garden shed. We sowed a few seeds in our garden some years ago, and it’s now a winter weed with us.

Look at the rootstock, spreading as wide as a fist with a taproot several feet deep (see p17), and the chest-high mass of stems and broad leaves, and you see why it can crowd out even its cousin hogweed. Alexanders is a biennial, and the first year of its life is spent building up that stealthy root system; the second year is given over to flowering, setting seed and then dying.

Our region is more or less at the northern edge of its wild-growing range. If it is spreading inland at a measurable rate it is also moving ever earlier in its growing habits. In a 17th-century herbal like that of John Parkinson (1640), alexanders is said to flower in June and July; we often have plants blooming in March.

It is an early responder to climate change, giving it competitive advantages over other plants and a nudge to us. In winter and early spring there isn’t a wealth of plants to gather, and foragers are taking the culinary hint. Alexanders is robust and can fill the ‘hunger gap’.

The history of alexanders

The scientific and common names are clearly Mediterranean. Archaeological finds suggest it was cultivated in Iron Age Greece (c1300–700BC), and the earliest written reference is in Theophrastus, the Greek ‘father of botany’ (c371–c287BC).

Its roots and shoots had become a popular potherb and vegetable by the time of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC. The English name Alexanders could be for the emperor, or indeed for the port in Egypt that he founded and which bore his name.

The plant’s Greek name hipposelinon means ‘horse parsley or celery’, while Columella, the Roman agricultural writer (ad4–70), knew alexanders as ‘myrrh of Achaea’, the then Latin name for Greece. A contemporary of Columella, the natural history writer Pliny (ad23/24–79), called it olusatrum, or ‘black (pot)herb’, the species name Linnaeus would choose for it in the mid-18th century. Pliny thought it a herb of exceptionally remarkable nature, and noted another name, zmyrnium, a reference to myrrh, the reputed taste of the plant’s juice.15

Ripe seeds of alexanders

The myrrh reference has followed the plant in its modern generic form Smyrnium. Some people do find the taste and scent myrrh-like, especially of the flower stalk, though others get more lovage in it; an old common name is black lovage.

There are as yet no British archaeological records of alexanders before the Roman invasion in AD43, but in 1911 seeds were found in a Roman-era well near Chepstow.

The consensus is that alexanders was among the plants that accompanied the Roman imperial takeover of Western Europe and North Africa. Some say the Romans used it as fodder for their horses as well as a boiled vegetable, a broth or the seeds as a condiment.

As both food and medicine alexanders continued to be a widely grown monastic plant in medieval times. Many scattered inland sightings of it in Britain relate to sites of kitchen gardens of former monastic houses.

By the time of the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s and 1540s, wild celery (Apium graveolens) was starting to be transformed by Italian agronomists into the blanched cultivated salad plant we know today.

Flower buds, showing the characteristic striped leaf bases that enclose them until they emerge

Around Europe celery’s milder taste came to be favoured over the stronger charms of alexanders, which lost popularity. In our own times alexanders is being newly appraised as a forageable weed.

Herbal & other uses of alexanders

Alexanders was classified as ‘hot and dry in the third degree’, and its actions were accordingly forceful. It was found to work strongly on the urinary and digestive systems, especially the seeds.

The English writer William Salmon (1710) summed up: alexanders effectually provokes Urine, helps the Strangury, and prevails against Gravel and Tartarous Matter in Reins and Bladder. In modern terms, he was calling it a diuretic, which cleared the urinary system, including kidney and bladder stones.

Roman writers knew alexanders as an emmenagogue, a herb to promote menstruation. Salmon confirmed that the plant powerfully provokes the Terms; it also expels the Birth (afterbirth). That is, 17it was and is a powerful uterine tonic, and should still be treated with caution during pregnancy.

Medieval root broths, made up of alexanders, celery, fennel and parsley, were used as purgatives for sluggish stomachs in the spring.

Alexanders was an ‘official’ herb of the apothecaries in the first London Pharmacopoeia (1618). But by Salmon’s herbal nearly a century later it had gone; he noted The Shops [ie apothecaries] keep nothing of this plant.

It was sliding out of favour in both medicine and cookery, though there are records of alexanders root sold for urinary problems in Covent Garden market in the late 18th century.

Of course, it does not follow that because alexanders has gone out of fashion it is no longer useful as a hedgerow medicine. The virtues the old herbalists championed remain valid, and clinical experimentation is opening up some intriguing new possibilities.

One is alexanders’ essential oil. Italian researchers in 2014 found that oil from the flowers induces apoptosis, or cell death, in human colon carcinoma cells. A 2017 finding is that this oil may be effective against the protozoal parasite causing African trypanosomiasis.

How to eat alexanders

Alexanders is also there to be eaten! It has a strong taste for our bland modern palates, which will usually prefer celery and parsnip to alexanders and lovage.

We find alexander leaves have a strong celery taste, and, like celery, quickly become stringy, so are best used young and in moderation. We use the taste to good effect to flavour salt (see p20).

Once the plant produces flower buds, the flavour of these and the stems is much milder and more floral. Larger stems need peeling. The flower buds and young stalks are tasty cooked with broccoli. They can also be used in sweet dishes and combine well with rhubarb or angelica.

The roots can be cooked like parsnips but usually have a stronger taste.

The simplest recipe of all is to collect the black seeds, and dry and grind them, either manually in a pepper mill or electrically in a coffee mill. Treat the seeds as a black pepper-like condiment and invite them onto your table; the urban forager John Rensten (2016) uses the seeds to replace pepper in his wild chai recipe.

Alexanders roots: first year plants on the left, a second year plant, before flowering, on the right.

Alexanders Tempura

Alexanders makes great tempura. You can use the leaf stalks during autumn and winter before they get too fibrous, soaking them to make them curl beautifully, or use the peeled flower stems cut into rings in spring. Both are delicious, but with subtle differences in flavour.

For the alexanders leaf stalks, cut them into roughly 8cm (3in) lengths and cut two or three slits about a centimetre (½ inch) into each end. Discard any that seem too stringy. Leave in cold water overnight or until the ends have curled as much as you want them to.

Pick the alexanders flower stalks while the plant is in bud, before the flowers open. Peel to remove the stringy bits and cut them into rings.

For the tempura batter, mix equal parts flour and cornflour (cornstarch) and mix with cold water to the thickness of cream, just thick enough to thinly coat the alexanders when they are dipped into it.

Roll the alexanders in flour, then dip into the batter. Shake off excess batter, and deep fry in vegetable oil until golden.

Variations: You can use use sparkling water instead of plain water in the tempura batter.

Alexanders Salt

This method can be used for many of the weeds in this book. We’ve used it most often with alexanders, nettle and ground elder.

The initial step is to dry your herb, then powder it – a clean coffee grinder works well. The powder can be sieved to remove any larger bits that didn’t get powdered. The herb powders can be used as they are, to add to recipes or sprinkle on food, or made into this flavoured salt.

Mix 1 part ground dried alexanders tops

with 4 parts coarse salt (we used grey French sea salt)

and 1 part water, adding just enough to moisten the other ingredients.

Leave to sit for half an hour or so, then spread out on a tray in a dehydrator or a cool oven to dry, crumbling it with your fingers from time to time as it dries so that you don’t get big clumps of salt.

Store in an airtight jar.

Alexanders & Red Cabbage Slaw

This is a wonderful winter salad. Alexanders comes into its own when there isn’t much fresh greenery to be found. We usually blanch the alexanders to tone down the taste a little, but if your leaves are very young and tender and you like the flavour, use them raw.

For 4 to 6 people.

Blanch a few handfuls of alexanders leaves in boiling water for about a minute. Older leaves may need a little longer. Taste to check. Drain and drop immediately into cold water.

Mix together in a bowl: 1 cup chopped blanched alexanders, 4 cups finely mandolined red cabbage and 1 finely sliced apple, cut into slivers.

Toss with about 4 tablespoons of dressing – use your favourite, or our recipe below.

Top with a handful of toasted pumpkin seeds, and serve with more on the side.

Alexanders Stems

Alexanders flower stems are best harvested just before the flowers open. They need to be peeled, and are then very tender and succulent. The flavour is less like celery than the leaves and more fragrant, like angelica.

They can be used in either sweet or savoury dishes, including the tempura on p18. Try simply braising them with a little garlic and oil. They make a tasty syrup with sugar and lemon juice.

The stems combine very well with rhubarb. Peel the alexanders stems and remove any stringy bits from the rhubarb. Cut into chunks and place in a baking dish.

Sprinkle with brown sugar or coconut blossom sugar, cover with a lid or foil, and bake at 175C/350F for about an hour or until they are tender. They are delicious as is, or add a crumble topping.