Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: ONE

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

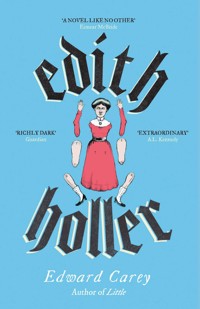

A witty and entrancing story of a young woman trapped in a ramshackle English playhouse and the mysterious figure who threatens its very survival, from the author of Little 'Extraordinary... funny, troubling, playful, magical and vastly energetic' A.L. Kennedy Norwich, 1901: Edith Holler spends her days among the eccentric denizens of the Holler Theatre, warned by her domineering father that the playhouse will literally tumble down if she should ever leave. Fascinated by tales of the city she knows only from afar, young Edith decides to write a play of her own about Mawther Meg, a monstrous figure said to have used the blood of countless children to make the local delicacy, Beetle Spread. But when her father suddenly announces his engagement to a peculiar woman named Margaret Unthank, Edith scrambles to protect her father, the theatre, and her play-the one thing that's truly hers-from the newcomer's sinister designs. Teeming with unforgettable characters and illuminated by Carey's trademark illustrations, Edith Holler is a surprisingly modern fable of one young woman's struggle to escape her family's control and craft her own creative destiny.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 533

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

‘An enjoyably uncategorisable and atmospheric book, a richly dark and idiosyncratic fairytale for grownups’

GUARDIAN

‘Filled with the author’s witty, curious observations and alive with his own illustrations, it’s a novel like no other’

EIMEAR MCBRIDE, AUTHOR OF THE CITY CHANGES ITS FACES

‘Funny, troubling, playful, magical and vastly energetic – sometimes all at once. Edith herself is a fierce, strange creature and entirely unforgettable’

A. L. KENNEDY, AUTHOR OF THE LITTLE SNAKE

‘There is much to admire in Carey’s inventive thespian netherworld and ingenious plotting’

MAILONSUNDAY

‘Nobody writes novels quite like those of Edward Carey. Flights of fantasy take off from bases of historical fact, while his own idiosyncratic illustrations pepper the page’

THETIMES

‘Singular – a dark delight from beginning to end’

ERIKA SWYLER, AUTHOR OF THEBOOKOFSPECULATION

‘Eldritch, raucous, blistering, beautiful, totally indelible’

MARIA DAHVANA HEADLEY, AUTHOR OF THEMEREWIFE

2‘This affirms the author’s standing as a major literary talent’

PUBLISHERSWEEKLY(STARRED REVIEW)

‘A wonderfully strange and quirky tale about the power of penning and performing tales’

KIRKUSREVIEWS

‘Carey excels in writing – and drawing! – peculiar characters, and the cast he creates for the macabre and fun EdithHolleris no exception’

NPRBOOK OF THE YEAR

‘At once delightful and uncanny, familiar and utterly unique, EdithHoller is a triumph from the first page to the last’

MOLLY GREELEY, AUTHOR OF MARVELOUS AND THE HEIRESS

PRAISE FOR

B: A Year in Plagues and Pencils

‘Characterful images are bound together here with words of wistfulness and modest hope’

OBSERVER

‘Whether a startled moggy or a panda-eyed Hamlet, each drawing is stamped with Carey’s unique style and off-kilter sensibility’

GRAEME MACRAE BURNET, AUTHOR OF CASE STUDY

‘There is so much sharp grace and so much generosity in Carey’s art; I loved this book, for its beauty, and for its tenacity of heart’

KATHERINE RUNDELL, AUTHOR OF THE GOLDEN MOLE

‘As Carey writes “There’s magic in the ordinary.” The best of us uncover it and pass it on. This book contains magic’

A. L. KENNEDY, AUTHOR OF THE LITTLE SNAKE

3PRAISE FOR

The Swallowed Man

‘Profound and delightful. It is a strange and tender parable of two maddening obsessions; parenting and art-making’

MAX PORTER, AUTHOR OF LANNY

‘Haunting. Geppetto’s voice, full of wistful overemphases and bewildered revelation, is absorbing as he takes in the oddity of his situation. And the book, sentence by sentence, offers much in which to luxuriate’

SUNDAYTIMES

‘A re-imagining of Pinocchio, told from the viewpoint of the beast-entrapped Geppetto, it surprises and delights, and saddens and gladdens, from start to finish’

BIGISSUE

‘A thing of physical beauty… The Swallowed Man can be read as an extended metaphor about the power of art’

THETIMES

‘A marvellous feat of storytelling that dives deep into the madness accompanying solitude and creativity’

DAILYMAIL

‘A tale with plenty to say about prickly father–son relationships and the responsibility that comes with creation’

MAILONSUNDAY

‘Inspired… a riff on the entwined themes of fatherhood and creative spark’

NEW YORK TIMES

‘A playful writer whose charming sentences are works of careful craftsmanship’

WASHINGTONPOST

‘When I say that this is a beautiful book, I mean that literally – the language as well as the art… A spectacular experience’

BILL GOLDSTEIN, NBC 4

PRAISE FOR

Little

‘Startlingly original… [Carey] finds and treasures the ironies and macabre eccentricities of Tussaud’s world. The pages are also enriched by his beautiful and haunting illustrations’

THETIMESBOOK OF THE YEAR

‘Weird, wonderful and unlike any other historical novel this year’

SUNDAYTIMESBOOK OF THE YEAR

‘Uniquely inventive… It is variously nightmarish, dreamy, sensual, emotionally affecting and very funny’

BIG ISSUE BOOK OF THE YEAR

‘Rich and engrossing, there is an extraordinary potency to Carey’s material… Visceral, vivid and moving’

GUARDIAN

‘A tale as moving as it is macabre’

MAILONSUNDAY

‘Strange and delightful’

VANITYFAIR

‘In this gloriously gruesome imagining of the girlhood of Marie Tussaud, mistress of wax, fleas will bite, rats will run and heads will roll and roll and roll… I bloody loved it’

SPECTATOR

‘A gripping novel of shy wit and darkly humorous occurrences… Mesmerising in its virtuosity’

IRISHINDEPENDENT

‘Clever and intriguing’

DAILYMAIL

‘This historical novel about the wax-sculptor who would become the world-renowned Madame Tussaud looks uncannily like a real life classic’

WASHINGTONPOST

‘Full of rich detail and beautiful illustrations… A rare treat that will stay with you long after you turn the final page’

HEAT 5

‘Moving, dark, and occasionally heartbreaking – a book to be read by the light of a flickering candle’

NIGEL SLATER, AUTHOR OF TOAST

‘Compelling… Carey’s story is cinematic in scope and fairy tale-like in its attention to coincidence, and to the fateful cycle of pride and fall’

TLS

‘A darkly fascinating tale packed full of vivid historical detail and quaint, engaging characters’

SUNDAYEXPRESS

‘By turns witty, ghoulish and poignant – a historical novel unlike any other’

BBCHISTORYMAGAZINE

‘Poignant and absorbing’

LITERARYREVIEW

‘Written with relentless energy, flair and finesse’

HERALD

‘Carey’s flair for macabre whimsy has drawn comparisons to Tim Burton – but while death haunts this story, Little is a novel that teems with life’

TIME

‘Marie’s story is fascinating in itself, but Carey’s talent makes her journey a thing of wonder’

NEWYORKTIMES

‘A startlingly remarkable flight of historical fancy where fact, fiction, tragedy and Grand Guignol collide’

INEWSPAPER

‘The beautifully told (and illustrated!) story of the life of Marie Tussaud, or how tall trees can grow from small seeds. An eccentric atmosphere, a macabre sense of humour, we experience this book with a sense of youthful joy. An unmissable book’

OLGA TOKARCZUK, AUTHOR OF THEEMPUSIUM

‘Compulsively readable: so canny and weird and surfeited with the reality of human capacity and ingenuity that I am stymied for comparison. Dickens and David Lynch? Defoe meets Atwood? Judge for yourself’

GREGORY MAGUIRE, AUTHOR OF WICKED6

7

8

9

For Oliver 10

11

That, if I then had waked after long sleep

Will make me sleep again; and then, in dreaming

The clouds methought would open and show riches

Ready to drop upon me, that, when I waked

I cried to dream again.

William Shakespeare, The Tempest

Act III, Scene ii

And sometimes sent my ships in fleets

All up and down among the sheets;

Or brought my trees and houses out,

And planted cities all about.

Robert Louis Stevenson,

‘The Land of Counterpane’

The Harlots cry from Street to Street

Shall weave Old Englands winding Sheet

The Winners Shout the Losers Curse

Dance before dead Englands Hearse

Every Night & every Morn

Some to Misery are Born

Every Morn and every Night

Some are Born to sweet delight

Some are Born to sweet delight

Some are Born to Endless Night

William Blake,

‘Auguries of Innocence’ 12

Persons Represented

edgar holler, an actor manager

clarence utting, a businessman

oliver mealing, a playwright

mr. penk, chief cloakroom attendant

mr. peat, stage door keeper

master cree, assistant stage door keeper

mr. leadham, in charge of theatre donkeys

mr. collin, an understudy

mr. jet, a fireman

john hawthorne, an assistant to the stage manager

aubrey unthank, a boy in a suit

margaret unthank, a businesswoman

agnesia unthank, her daughter

nora holler, wardrobe mistress

belinda holler, backstage cleaner, sister to Edgar Holler

jenny garner, an actress

flora bignell, wig curler

miss tebby, prompt mistress

mrs. stead, puppet mistress

edith holler, playwright, daughter to Edgar Holler

Other actors and workers of the Holler Theatre, also insects and spirits found therein

SCENE. The Holler Theatre, Theatre Street, Norwich, 1901 14

Contents

I

A tour of my theatre.

1.

At home.

In Great Britain, in England, on the bump on the right that is about halfway down the country, by which I mean the rounded bit that has a pleasant and generous look to it, something like the handle of a favourite teacup, or the curve of a lovely ear, is East Anglia. The top of that bump is the county of Norfolk. A little to the right of the centre of Norfolk is a city called Norwich. Norwich, seen upon a map, is roughly the shape of a leg of mutton. In the centre-most point of Norwich, around the tip of the shank, is a castle called Norwich Castle. It was built by the Normans and is the type of castle called a keep. Ten minutes’ walk from the castle is the Holler Theatre. I have lived here, upon Theatre Street, my whole life. There are side streets around the building, they are called Chapelfield East and Chantry Road, and there is our neighbour the Assembly House and a little beyond that the church of St. Stephen, and that is the whole box around the theatre. I was born here and have not been anywhere else since, not even once.

The city of Norwich is visible to me from the theatre roof. The cathedral spire I can see, for example, and the castle on its high mound. Under the mound there is supposed to be a king called Gurgunt. Some say he founded the city, and that he waits in the deep with a whole army ready to rescue Norwich should it come to great peril. It is just a tale certainly, but a wonder tale nevertheless – it makes you feel that magic is local. Finally, I can see the back of the Bethel Hospital, founded in 1725 for curable lunatics. 18

I see all these buildings because they are tall and large and declare themselves well. But I have never once stepped inside any of them. I don’t go out at all, but stay in perpetual. For a better understanding of my life, you may buy a miniature Holler Theatre in card form, from Jarrold & Sons, the stationer, 1–11 London Street, which can be assembled at home. It is a beautiful toy and with it you may mount your own in-house performances; price 6d. But I live in the actual building.

There is a sign outside the theatre, the real theatre, that stays there day and night. No matter what play we are playing, still this sign stays the same; even when the theatre is dark, it remains. The sign says the holler theatre, home of the child who may never leave. Just next to the sign is a large plate glass window, and through the window can be seen a little room where the child who may never leave sits and is observed.

It is in this room that I have often performed my one-person dumb shows for the people of Norwich. I get into costume and act out all the parts. The people of Norwich come and watch me, and on a good day I may raise a crowd of fifty or more. Here have I been the mangy ghost dog of Norfolk mythology, Black Shuck, who roams the desolate coastline and the graveyards filled 19with Norfolk dead; indeed, the sight of the hound is a warning of imminent death. As Shuck, I growl and howl (without making a sound) at the people. Or else I am Boudicca, queen of the Iceni tribe, holding in my hand the head of a Roman soldier (got from the props room); or else, more quietly yet, I am Julian of Norwich, who was a woman who lived not ten minutes’ walk from here, long ago, back in the fourteenth century, and was an anchorite, voluntarily walled up inside the church of St. Julian, on St. Julian’s Alley in the district of Richmond on the Hill. She was the first woman to write a book in English, the very first. (We are both writers, Julian and I. I always keep a notebook and pencil about me.) She had visions, she did, and I act them out for Norwich, Norfolk.

I have visions, too, of a kind, when I let my imagination go as wild as Black Shuck. I have stories and tales for every day of the week. But most of all I am the discoverer of terrible secrets, I am Norwich’s detective, and I have uncovered something dark and wicked – which I shall come to by and by, and for which afterwards I may be blessed or cursed.

When I am done with my performance I draw the curtains, so that Norwich may know I am no longer available, and that the spectacle is done with – and then it may seem to them that I have died, or that perhaps I was never truly there. Sometimes, fairly often, when I am not at my post, a doll of me, the hard face made by the theatre’s puppet mistress, Mrs. Stead, the cloth body by the wardrobe mistress, Aunt Nora, sits there in my place. (When the doll of me needs to be replaced, if I have outgrown it or it has been accidentally damaged, its material is always taken apart and used elsewhere – nothing does go to waste in this theatre and all must be useful.) (On occasions I pretend to be the doll.) (And sometimes the doll and I sit together and we are twins. I make the 20doll move more than me, just to confuse.) (It must seem to Norwich that I don’t really exist at all, that I am only a person-sized puppet or doll. And perhaps I am, I think that sometimes. Father says it’s good they are not certain, it is an excellent device.)

I am Edith Holler. I am twelve years old. I am famous.

The year is 1901. The month is March, by which you’ll understand that the Christmas decorations have long been put away and that the pantomime season is quite ended. And what is most nationally pertinent is that the old queen is fresh dead. And the new king, Edward, looks like he has only a little life left himself.

My confinement is for my own safety. I cannot go out, for to go out would kill me.

I have been ill much of my childhood, laid often in my sickbed. They thought I should not last. It was diphtheria and it was meningitis and it was pneumonia; one woe, as they say, did follow on another’s heels. I was ill at my birth, and my own dear mother did die then – and so death is never far away. I should have died, I lay lost to the world in my bedroom, and they fussed over me. I have always been frail, Father is terrified for my life, and so I must keep indoors, and so I do.

And, which is even more: not only do my illnesses keep me inside, but there is also in addition a nasty curse from an unhappy old actress, which was given to me at my christening. But, though I do not travel, yet there is much to wonder over from my confinement, both within and without. From the walls of the Bethel Hospital, I do hear the dismayed inhabitants often enough. The hospital is just across Theatre Street, and from time to time I watch as the inmates in their courtyard act out their own strange one-man shows. Sometimes some of our actors suffer from a persistent confusion and they have need of the Bethel Hospital. I have 21known actresses to go across the road, as we call it, and never come back again. Never once.

Though naturally I cannot go out to school, from the roof I can see two gloomy factories of learning. Crooks Place Boarding School, very close to the theatre, is where some two hundred boys are educated and live and, like me, don’t get out much. I have watched the boys in their uniform when they come to their exercise yard, have seen them fight one another and play with conkers on a string. After that, I had Mrs. Cudden, one of the seamstresses, bring me in some conkers, and for a little while everything was conkers with me. I felt I was closer to the boys of Crooks Place then, and I found clothes like theirs in the wardrobe and went about for a while as a young fellow and I insisted they called me Bartholomew. But the distant boys never returned my waves – perhaps after all I was too far away; I did spy them only with my old opera glasses – and at last I said stuff them and their dull education. Not for me the conker, after all. It is not natural to me.

Another neighbouring property is the Assembly House. This was built as a place of entertainment and dancing, but in 1876 they took away all the entertainment and dancing – said no to the people falling in love, no to the married couples come for music, no to laughter and to cake, no to gaiety and to passion. Instead, they filled the beautiful place with learning and tore out all the light. They threw away all the young males and said, Don’t you dare come again, no, you must never. Instead they have there only girls. The girls go in, all uniformed, of a morning, to be taught how to come out proper Norwich ladies. They never wave back at me in their dull lines but look only downward, for I, they seem to say, am not an upright specimen. They think me like Peter the Wild Boy, a famous feral person who came from a woodland outside of the town of Hamelin, in Germany, and once lived in our city. But I cry for the occupants of the Norwich School for Girls. That wasn’t the point of that building, I have called to them from our roof. No, no, you have ruined it with your learning, with all the strict women come to 22suffocate love inside. You have killed the Assembly House, now it is merely another manufacturing shop and the soot that comes from the chimneys is all Latin and deportment.

I take a different school.

For a long time Mr. Lent, one of the old actors, was my teacher. He would make me speak the proper English and not slide into the Broad Norfolk that we have hereabouts. It never did for the daughter of my father, the great actor, to have a child that blurted ollustfor always or squitfor nonsense or muckwashfor sweat. Shakespeare must not be spoken with a Norfolk accent.

But I never speak onstage, I protested.

Even so, said Mr. Lent, it hurts the ears and we’ll have none of it. Mr. Lent is gone now, but his lessons have not died with him. And since his passing I have greater study.

In my bedroom do I consider the history of Norwich. For, though twelve, I wonder if I am perhaps also ancient. In my bedroom, where I sit, I have about me all my toys, but also maps of Norwich throughout the ages. For Father had said to me, one day as I lay abed: You must not go out, but Norwich may come in. Ever after, I have made Norwich my great subject. Norwich is outside the dark interior of the theatre, and so to me Norwich represents life and space, and so as I ailed I had the idea that Norwich itself might save me. I demanded proof of Norwich, proof of it in all its different centuries. I clung to the city as I clung to life. I was given all manner of books and papers upon Norwich, Norfolk, for its study was all that would comfort me, and the more I studied the better I felt.

Norwich was my medicine. Norwich is my life. I think, though twelve, I must know Norwich better than anyone.

At first, I got all my information regarding Norwich from the stacks of shelves of the Norfolk and Norwich Subscription Library, which is on Guildhall Street. Norwich is the first city in Britain to have a public library. I eat it all up and remember much of it and it sustains me. Medieval Norwich, I may tell you, for example, had fifty-seven churches, which is very many. One of my uncles or 23aunts would fetch the books for me, but it was not long before I had read all the library had to tell me, and then I began to get sicker again, and my father in his desperation knew not what to do. It was Mrs. Stead, the puppet mistress, who understood the remedy and proclaimed it simply, ‘Yet more Norwich.’ And she, being an ancient and sensible and practical woman, was able to encourage the librarians on my behalf and new material was found. So I came by the Assize Rolls and the Assembly Rolls, the Quarter Sessions books, the Mayor’s Court books. Mrs. Stead set out in the morning with her empty basket, walked the short journey to Guildhall Street, and would return with new volumes. She would plump my pillows and sit me up in bed and say to me, ‘What have we here? Ah, I see LeetJurisdictionintheCityofNorwich. And what else? Here then the BookofPleas. And here we have the NorwichCensusofthePoor. There, Edith, that should keep you quiet for a while.’

Backdrop for a card theatre.

Those brave and clever librarians who, finding this need of mine an interest and a challenge, sought out their colleagues around the city, and so came papers from the Guildhall library, from the 24Cathedral library, from the library at City Hall. And thus I read on, my pale, long fingers upon Norwich, and I came to learn so much. I saw volumes from the poorhouse, from the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital, I read bastardy records, settlement certificates and removal notices, and many a load of old newspapers and worn-out bill stickers. It was a pleasure for them in the library, I think, to seek out these obscure pages and have them delivered, ever by Mrs. Stead, to a child that they had never met but had merely seen through a plate glass window – made, incidentally, on Wensum Street by the Norwich Glass Company.

As I read on – for I had time where others did not, and I spent patience upon so much communication that had been left lonely for many years – I began at first to have suspicions, and then to grow a terrible certainty, that something abominable was hiding in the pages of Norwich’s history. In the annals of the Surveyors, in the pages of reports from the Overseers of the Poor, in the statements of the Vestry and Parochial Church Council, I would find, almost always in single lines, disturbing reports: Child of Thomas Pelling wanting, Lakenham, last seen Fybridge; ward of Norwich, Carrow, missing at evensong; Mary White, child, & Richard Loftus, child, Colegate, not seen these past 100 days.A terrible secret began to grow in me, and the discovery of it sent me back into my sickbed and seemed to call me unto death. Indeed, I thought the secret would kill me, until at last I understood that it was the secret that was keeping me alive – and that I must tell it, I must spill my secret of Norwich upon the streets of Norwich, for I knew Norwich, though I have never gone out into it, better than Norwich knew herself.

Norwich steals life. Norwich murders.

Norwich has lost lives in so many ways over centuries, through fire and flood, through cruelty and negligence. Yes, yes, you will say, no doubt: but this is true of many a place. And you would surely be right. But here in this city of mine I have discovered something else, something unexplainable, something terrible that has been going on for centuries, that I rush to set it down: so many children have 25gone missing, there are lost children everywhere. From all corners of Norwich, from Conesford and Wymer, from Mancroft and Over the Water. Nor were they ever found. Not a one.

Norwich, I must own, is famous for missing children. In 1144 a tanner’s apprentice named William disappeared and they blamed the Norwich Jewry, housed between Haymarket and Oxford Street, saying they had murdered the boy for their rituals. And afterwards many Jews were murdered in retaliation. It is the first record of medieval blood libel to be found in all of Europe, here in our Norwich city. Now they acknowledge it wasn’t the Jews after all, but who then did murder young William, whose poor stabbed body was found in Thorpe Wood? No one can say, and though this murder did certainly happen before all the other children went missing, yet it seems to me a kind of precursor or warning.

Where do they go to, these missing children of Norwich? A single child missing will command the attention of an entire city, especially if that child is from a prosperous family: then everyone will look everywhere in suspicion, then the city will hold that missing face secure in its imagination. But what if there were a hundred and more missing, and all at a time – a hundred a year, say – then missing children will be a commonplace thing, and so seeing the bill posters with lists of the missing will become ordinary, and ordinary means invisible. It has gone on for centuries, I have found it out: children go missing in Norwich at a terrible number. Some five hundred over the years from Pockthorpe alone. True, sometimes in quiet seasons, maybe only four or five are lost, but this quietness is generally followed by a deluge of fifty or more suddenly absented.

Ah, you will say, let us call this missing of yours instead Small Pox and all is mended. Perhaps – but where then are the bodies? Why are their names in no death registers? Are these poorchildren? you will ask then. And I must say yes, mostly, but not always. Can you prove it, that these children were lost? you will ask. And so then I can show you the years – and centuries – of notices of children lost. It is a very incautious city, you will say. Yes, yes, but I will say: who takes the 26children and where do they go? And then you will say – for you have had a moment to consider, and you do not wish to descend with me into dark knowledge, lest it threaten the very foundations of history and governance – No, no, it is all too much, I cannot believe it. And in response I will say, You choose not to believe, because it is too terrible a thing, and so you ignore it – and thus it goes on.

You will be in a bad mood with me by then, and irritated that a child, a girl, could so arraign you, and you will not acknowledge your ignorance, you will decide to refuse it. You will say to me, What a horrible child you are. Why cause this dark trouble? You have imagined it all. And have I?

Sometimes I doubt myself, and yet again and again I see in the ancient ledgers: child lost, children missing, boy twelve absent, girl seven unaccounted for, twins nine misplaced. What happened, I ask you, to Lolly Bowes? How did the life of George Kellet end? Who saw Nathaniel Bradshaw at his last, or Millie Bolton or Alfred Waltham? And for those lost children I do call out. How many children have you lost, O Norwich? Where, where is Polly Stimpson? Whatever happened to Martha Higg? Simon Pottergate? I begin to suspect that only people who keep very still may catch the truth that is there before us, for everyone else is too busy. Only I, in illness, with my time and study, in the gaslight in my bedroom, with books as my playfellows – only I might hear such truth in the small hours of the day, like the little tapping of a deathwatch beetle that can only be heard when all else is silent. It is a terrible thing, this knowledge of Norwich. I sit beside my secret day and night – a whole legion of lost children shut out in darkness – and it has made me ill. And I cannot unlearn it.

It was last summer when I came into my horrible knowledge, when I concluded at last that there was no doubting it anymore. Then I called out the names, that they might be heard again: Good morning, someone might say to me, and in response I would reply, MollyCruickshank!In the afternoon, at teatime, I would wonder aloud, EdwinBagshot?And when they tucked me in at night I would challenge them to know Samuel Carter,never seenagain.

27In response to so many names, my aunts and uncles made me sit out on the roof, looking at Norwich. There I stretched out my hands and wondered over my terrible discovery, I shivered over it, it made me vomit. Yet I own I did feel a little better being on the roof, up there standing beside the statue up at that height at the tip of the building’s façade. The statue is a Greek-looking lady and some say that she is Euterpe (the muse of lyric poetry) and others that she is Melpomene (the muse of tragedy) and some have wondered if she is Boudicca because she is holding a spear, yet that spear I think was actually only a support that once held a mask or a harp which the poor stone lady has long since dropped. Most people though forget she’s there at all, and fail to notice her atop the building. I lean beside the stained statue and look out at Norwich and am calmed, for there is so much to see there, and from my view I saw no children being forcibly lost. So I pretended, when I could, that all might be well. Look there, after all: at a right angle to the Bethel Hospital are the Chapelfield Gardens, which I can peer into and thus see a little nature and people walking about, and in the summer sometimes I can spy, upon the park benches, small scenes of love – for love may be found in my Norwich too. In the park I can see the Chapelfield Pagoda, a great iron pavilion. It looks Japanese but it was made by one of the sons of Norwich, or at least from nearby Wymondham, a man called Jeckyll did it. The pagoda is famous here, like me. But poor Mr. Jeckyll went mad and he was taken to the Bethel Hospital, across the street from both the theatre and the park. They never cured him, he died there under lock and key. I wonder if, like me, he looked out from a high window into Chapelfield Gardens at his rusting construction, and if that was a blessing or a sadness.

I wonder who will believe the truth of my terrible secret, or will they one day, as they did with Mr. Jeckyll, take me to the place that says it cures, though it doesn’t always. And then, if I am cured, will I cease to believe my secret? Will the cure let my hair thicken, make my long face rounder, my skin pinker? Will the cure let me travel? And I wonder, would I care to be cured? Could I trust in it?

28I do think I’d like to step out, if I could. Father says I mustn’t, though, and I shouldn’t like to worry Father, he can become very excitable if worried. He is as protective of me as many a parent found in fairy tales. And so I go up to the roof and look out all around at Norwich and feel a little calmed.

What I can’t see of Norwich, I can sometimes smell into. The fish market is close by, and the Market Place is hard by that, and these businesses have many things to sniff at. Sometimes I smell flowers and sometimes meat, but usually the fish beats out all the others. And yet, when the wind is right, even the fish will be outdone by the thick air of Beetle Spread.

Ah, now, it is most pertinent that I talk of the beetle. There’s generally, in the air of our city, a slight tang of Beetle Spread; we of Norwich have it in our lungs always. Beetle Spread is known of course throughout the country and even beyond. It comes in small 2 oz. jars, filled at the factory in Norwich, which is larger even than the cathedral. The symbol on the labels of Beetle Spread is a deathwatch beetle. Ah, you will say, here is a second mention of a deathwatch beetle!, and it is true I do often have these creatures in my mind. Our city has its most famous tale connected to Beetle Spread. You will probably know this tale already, but I’ll mention it here quickly just in case, because the missing children of Norwich are very connected to this ancient story – indeed, they are truly tangled up in it.

Perhaps you are not from Norwich. Perhaps you have never come here yet. We that live on the eastern side of the country are often forgot, I think, and so strange things may happen here and not be noticed far beyond – in London, say, or in Edinburgh. You may turn your back on us, but we do likewise upon you. We exist without you, we have no need of you. And yet perhaps we do, for we have lived alone in our deep east for so long that children go missing and ancient tales do have modern life. All that follows below – all my terrible understanding, all my study, all the black secrets – will not be comprehended without knowing the Norwich folk tale connected to Beetle Spread, for it is upon that tale that my discovery is centred. 29

Sometime in the fourteenth century (during the time of Julian the anchorite), Norwich was overcome by a great plague of beetles. The beetles, which are especially common in the flat, damp lands of East Anglia, are larger in this part of the world. An ordinary deathwatch beetle grows up to a half inch in length, but here East Anglian deathwatches have been known to reach near two inches. And these beetles threatened to devour the city, which was then mostly made of wood. All was nearly lost, it is said, and would have been entirely, were it not for a woman named Meg Utting.

She had ever been strange and obscure, this Meg; some said she was mad, others that she was evil, but most of all people said she was very hungry. A poor, unmarried woman, and such people can be especially unlucky. Only her sister would speak to her, and that sister would give her half her meagre victuals and so kept them both alive. But now she was about to become our city’s saviour, for Meg Utting had contrived a way of collecting the beetles. One afternoon, in her despair, knocking her head against the oak beam of her hearth, she noticed beetles come rushing out; she crushed them underfoot. In her curiosity, she banged her head once more, and yet more beetles came. By this action, unbeknownst to her, she was simulating the reverberations of some primal beetle mating call, and thereby she brought beetles in swarms to her house. The more she banged her head against the beam, creating a rhythmic thump, the more the beetles rushed towards her. The streets around her home, Fishergate Street, Peacock Street, and Cowgate Street, became so thick with beetles that it was as though a strange muddy river were flowing towards her in a terrible hurry, until the waves broke at the house of Meg Utting.

The best way of demolishing the pest, Meg discovered, was to cook it. She had a great pot on her stove, and when it filled with beetles – by now they were dropping from the ceiling – she let them simmer and boil. What I find most extraordinary about this story, however, is what happened next: somehow, Meg discovered that 30the cooked beetles, all mixed together, had a taste that was quite marvellous.

Meg Utting began to sell her beetle jam, as she called it then, and soon all of Norwich came to eat it. She made a small fortune from it, in time, and even married a man much younger than herself, a freeman of the city. She had a sister, Meg did, as already mentioned, but it is said that she never helped her sister when she came asking, and the sister died in poverty and of starvation. But that sister’s last words, it is said, were to curse Meg, and to proclaim that one day a child would come into her life and that child would be the death of her. ‘Maybe today, maybe tomorrow, maybe not for many a year, but the child shall come, and that shall mean your end.’

Eventually – it may have been from all the knocking of the head against the beam, or perhaps some of the beetles had got inside her head – Meg Utting went mad. She was seen about the streets, crying out, threatening the children. She came to be mockingly called Mawther Meg, mawtherbeing our local, mostly ill-meant word for girl or woman; also, our Norfolk word for scarecrow is mawkin, and I have often felt these words and their meanings – the beetle woman and the bird scarer – must be related. This name was often reduced, further, to Maw Meg.

It was around this time that the children of Norwich first started disappearing. Some people muttered that Mawther Meg had eaten them or drowned them in the Beetle Spread. That people were eating their own children now on buttered bread. Some mused that she was an ancient, evil spirit come up from hell; others that she had mated with a great beetle devil that lived in the nearby Thorpe marshes. Whatever the truth, Meg Utting grew thinner and thinner, despite all the Beetle Spread, until she appeared the physical embodiment of Hunger itself.

It is certain that from this date the children of Norwich started to be lost in large numbers.

31When a child disappeared, the reason given for it was the legend of Maw Meg. Crowds of Norwich hid behind the terrible story. Be careful or Maw Meg will get you, they warned, and it was a great game – but also, you see, a child did go missing and was never found.

Who the real Maw Meg was cannot now be known. But what is certain is that she gave us the Spread, and the making of it became a great business, and we have had it here with us ever since. Every jar of Beetle Spread, even now, is said to contain at least one deathwatch beetle. There is a statue of Meg near the Erpingham Gate of Norwich Cathedral (named after Sir Thomas Erpingham, who led the archers at the Battle of Agincourt), and beside her is a statue of our other great Norfolk hero, Horatio Nelson, who went to the Norwich School nearby. People who come to Norwich, I am told, most often head to see the statue of Maw Meg Utting; indeed it is a custom to touch one or two of the bronze beetles at the statue’s feet. Touching these beetles is supposed to bring you good health (likewise the Spread), and so the statue of Meg Utting is much more touched than the one of Horatio Nelson, for touching Horatio Nelson is not supposed to do you any good at all, and may even diminish your person – the admiral’s statue having but one arm.

In my bedroom is my typewriter table and upon it is my seaweed-coloured typewriter. It is like a building, this machine. Like a parliament or opera house upon my table. Father gave it to me. It is very modern. It came up from London in its own crate and says in golden letters the english standard typewriter, 2 Leadenhall St., London EC. It is not a children’s object, but beside it I have a toy model of HMS Victory.

Like many a Norwich child, I also keep close at hand the toy variously called the Beetle Rattle or the Deathwatch Dummy or the Beetle Clacker, sometimes just called the Meg Peg. It is, as you probably know, two wooden spoons bound together with leather straps, bowl against bowl; you pull back one spoon from the other, stretching the leather, and 32then let it go so that it makes a loud clack that is supposed to replicate the noise of a deathwatch beetle. The toy is supposed to summon beetles. I myself have never had much luck with it and consider it a dull enough project. But I do hear, sometimes, the noise of the Meg Pegs as the Norwich children play in the park.

Forgive me: I was talking of the Spread. Every one of the jars says UTTING’S BEETLE SPREAD and in slightly smaller letters of norwich. People of Norwich (and many who are not) eat Beetle Spread on toast or cheese or fruit or chicken or ham or bacon, or place a spoon of it in a mug of hot water and drink it in the winter. It is a most versatile substance, said to be beneficial against most ailments. In the summer, also, if spread on strips of paper, it can catch flies.

We of Norwich are very proud of Beetle Spread. Here, where the Spread is made, the air itself is often spread with it. Sometimes the city may fall under a dark and ruddy fog, caused by an accident at the factory, when some quantity of Spread has become airborne. On such occasions we all go inside (I don’t mean me of course, for I’ve never left) and wait for the cloud to pass. Afterwards, we wipe our windows with newspapers (I don’t mean me of course), and the newspapers always come away red. Have I mentioned that Beetle Spread is red? Oh, but surely you’ll know that. It has been red for centuries, though originally it was black or brown. It is red now because at some point, no one can say exactly when, madder root was added to the ingredients. We have much madder root in our Norfolk and have for a long time used it in our dyeing of clothes – hence the famous red Norwich shawl – and hence the square of the city called the Maddermarket, which is where they sell the root. At one time our River Wensum ran red because of the dyeing of materials, and today it runs red on account of excess Beetle Spread as it flows from the factory. I cannot see the River Wensum, I have indeed never seen it, but I know it is there, for I have been told about 33it often enough, and I do believe it is a truth that if I got into the Wensum and swam (I cannot swim), getting very red I suppose at first but then less and less so, I would arrive at last to a place called Great Yarmouth. But I don’t go swimming to any (Yare) mouth great or small, I stay here inside the bounds of Theatre Street, Chapelfield East, Chantry Road and Assembly House.

Here in the theatre, if we are low on pins or spirit gum, we have often been known to fix our wigs or beards with a little Beetle Spread. One of the disadvantages of the Spread is that people can roll a small ball of it and pop it in their mouths and then chew it for hours (making their teeth red – oh, the red teeth of Norwich!) and then, inevitably, after a time, after the taste has gone or jaw ache has set in, they often spit it out, on the street or even upon our front-of-house carpets (which are red in colour because of the Spread, in the hopes of disguising it). Cleaning up after Beetle Spread gum is a time-consuming business. The smell of the Spread is hard to explain to the uninitiated. It is like a concentrate of meats. It is like a new animal not yet named. It is like a strange and uninvited intimacy.

Something else about Beetle Spread: I think the missing children are inside it.

I know this was alluded to before, but then it was said in jest and to frit the Norwich slums. But I think it is true. I came to this one morning as I sat propped up by pillows in my sickbed, studying the Norwich lost. A piece of toast beside me with butter and Spread. I read about the lost children, I took a bite of toast. Ernest Ridings I read, and I took a bite of toast. Bess Tollymash I read, and I took a bite of toast. Susie Headley I read, and I took a bite of toast. And then I stopped. I dropped the toast, it fell Spread-side down upon my sheets, a great red mark there.

Oh!

I no longer eat the Beetle Spread. I will not have it near me.

2.

Birth of a playwright.

Perhaps I should describe myself. How to turn my eyes upon my very own self? To give you the correct idea of me?

I am more bony than bonny, I admit, and just a little taller than average. I am flat of breast and likewise of feet. My hands and feet, though narrow, are rather large, so I may grow long in time, and one day I may fill out and thus become a woman.

I look a bit washed out, a bit rag doll you might say. My skin is very pale, almost all white. My own hair is a sort of greyish red, somewhat fair but a dull colour, and sometimes seems as ashy as my flesh, and so it may be said I am only one colour altogether. Except my eyes, which, like Father’s, are a very pale blue. ‘You look like you’ve seen a ghost’ is a common enough observation. ‘You look like a ghost’ is not unheard-of either.

Well, then, if I am monochrome, I do embrace it. I clothe myself in greys and whites. I am perhaps a little mouldy, a touch mildewed, slightly foxed; I am an old book, a little yellowed, mothlike. I do need, probably, a little airing out. Also I have become crooked, perhaps, being so shut up for so long. My body grows awkwardly on account of my illnesses and does not mature. My voice is generally rather raspy.

What else must I say, or else my life be misunderstood?

I have told one story from Norwich; it is necessary that I balance it with one from within the theatre. How I have relied on stories in my sickbed. They have saved me certainly. For we are made of stories, surely, and some are true and some are not, and some are 35part truth and part lie – well, and perhaps that can be said of all stories. But there is a particular story of this theatre that I am told a great deal, everyone here knows a version of it, but it is Father who is the most regular teller and indeed he does narrate it very dramatically. It is dear to him, because the story is about me. It is the story of my curse.

It happened at my christening – which was upon the stage, this was a family custom, we always had the Bishop of Norwich come in for it, the stage set up for the cathedral in which Thomas à Becket was murdered – and chiefly concerns one of my old aunts. Everyone here to me is uncle or aunt, you see, or, if they are younger, cousins – though we are related not necessarily by blood but by profession. This particular aunt was no longer allowed to perform on account of her failure to remember her lines, though she insisted she could. She was not my real aunt, but a woman named Lorena Bignell, and came originally from Lowestoft in Suffolk. There are always several retired actors about; they are looked after here and find small jobs about the theatre – Father keeps them useful for as long as is possible, and they do on the whole prefer to be around the theatre than in some kennel for old people or in the workhouse or in the Bethel Hospital.

Since her banishment, Lorena Bignell had kept herself miserable in the wardrobe until she delivered her last, and most magnificent, performance. She appeared in one of the theatre’s grand boxes attired in a yellowed and ripped wedding dress, and in front of my family and all the actors, all the stagehands and crew, the orchestra, the puppeteers and the laundresses and wig people and carpenters and candlemen (this was shortly before the gas was put in), and even the prompter, Lorena Bignell spat and cried and placed a curse upon me. She was very fine and exact in everything she delivered, not a word was garbled; all was crystal clear and unforgettable. If I ever should set foot upon Norwich streets, she proclaimed, I would die. Then, as if this itself were insufficient, she added – after a grating moan – not only that I would die, but that the entire theatre would come tumbling down. 36

Ah, I see now that I must clarify.

Do not please think that this whole business was prompted by my father not inviting my aunt to the christening – that I’m simply reviving the story of SleepingBeauty, performed often upon our stage. No, Lorena Bignell had been invited. In her day, she had been a most moving tragedian. The trouble was that she had been abused and murdered, haunted and despised, so many times onstage that the plays had leaked into her mind, and unlike the greasepaint it could no longer be washed off. She had become a woman much given to howling, very angry and uncertain, twitchy and confused. Yes, the poor woman had been ill-used – and it was my father, playing, as he so often did, the villain, who had done it all to her. And so, to get at him, Bignell cursed me. But it was more than that. Oh, she was a good one, and thorough. It was a performance so distinguished that it is still spoken of today. Some argue that she cheated, that her methods were not to be found in the script, that strictly speaking her performance was not theatre at all but something more rightly called a ‘demonstration’. (Norwich, may I say, is a famous city for rioting; much town property was destroyed in one of our worst riots, in 1766, and for their part in the uprising two men, John Hall and David Long, were hanged at Norwich Castle.) Others say that Lorena Bignell did in fact work from the script but rewrote it to serve her own ends. And that last I would agree with, because this extraordinary gesture of hers, within a playhouse, in front of a sizable audience, rewrote my entire life.

So then. Here it is, as it has been told to me: Aunt Lorena Bignell died in an explosion of blood.

37My aunt spurted from the balcony onto the stage and everywhere in between. She was afterwards to be found, in fact, everywhere – all over the stalls, for example, and the balcony was most spoiled. A good portion of her had reached the stage itself, which no doubt would have made her very happy. For days thereafter there was much mopping and scrubbing – the remaining Bignell was worse than even Beetle Spread – and it took a time, I am told, for the smell to surrender.

To this day, no one is quite sure how my aunt Lorena exploded. It was the most marvellous effect. Several members of my family, myself included – using dummies, you understand – have tried to recreate her extraordinary exit, but the result has always been a disappointment. She had burst into a hundred thousand bits, she had spread herself all over the auditorium. I was baptised twice, once in blessed holy water and once also – there were drops dotted about my gown – in blood, in ruddy flecks provided by my very recently expired so-called relative. This same christening gown is now framed and hung front of house, so that all may see the old blood upon it and remember my curse. Thus was I marked on my first day of life. The many people who had come to witness my christening were given also an Aunt Lorena bath; thereafter, thus besmirched, they walked Aunt Lorena severally all about our city, to the portions called Tombland (it is called this not because of tombs but from an old Scandinavian word meaning ‘empty space’) and Heigham, Millgate and Hellesdon, Lakenham and Pockthorpe, Old Catton and Sprowston, and even into their homes, because she was there upon their clothes and skin.

In consequence of this event, unlike my aunt Lorena in so many bits, I am not allowed out. My aunt’s explosion had sealed the severity of her curse. Without it, an exception might perhaps have been made, some way found to circumvent her fury. But Aunt had gone out in a large red puff, a crimson explosion, and that had sealed me, forevermore, inside. There is even a small bronze plaque affixed to the railing of the box: 38

UPONTHISSPOTEXPLODED

LORENAAUGUSTABIGNELL

And thus began my father’s worrying. Not only had Mother died, but I was ill and cursed right from the start. The actors shook their heads. The doctors shook their heads. There was death all about me. I had not much time; Oh, the poor child. And so I was born to stay inside.

I should include a very small addendum here. It is possible that this story is an exaggeration; it is quite possible that my poor aunt did not explode as such, indeed she had been coughing a good deal, I have been told, and it is very possible that in fact my aunt, as a result of a severe lung infection, haemorrhaged, and that a little blood did indeed come from her mouth, perhaps even a quantity. It is difficult, at this distance, to know exactly. Certainly she died, and probably she bled. We who live in the theatre here have some belief in magical things. Rules that apply to other buildings do not apply here. In the theatre we strive to make the impossible possible, to believe in and convince our public of fantastical personages and happenings. Very frequently, for example, we bring back old dead kings (not Gurgunt under Norwich Castle, but the ones often called Henry or Richard) and have them alive here upon our stage. All this makes it seem possible, then, that Lorena did explode, but also that she merely leaked. I cannot say which is the truth. But in either case she did deliver her curse. In either case she did die very shortly afterwards, perhaps even instantly. And so, as we are a very suspicious people – we believe in curses and in dying curses particularly – and so here I am and ever likely to remain.

It is well known that ravens must be kept at the Tower of London, or else the Crown will fall and Britain too. That is a London belief. We in the east of England have our own thinking: it is lucky to have a bent sixpence in your pocket; if you shiver, someone is walking over your future grave; if you break two things, you will surely break a third; if you put a broom in the corner, you are sure to receive 39strangers; if you stumble upstairs, you will marry before the year ends; if you eat pork marrow, you will go mad; you must never look at a new moon through glass; a horse has the power to see ghosts; you must always burn a tooth after it has been drawn, otherwise, if said tooth should be eaten by a dog, you will grow a dog’s tooth; a child cursed indoors will die outdoors.

Well, then, I am one of those.

My prison. My palace. My home. Every day and only.

It is a very old building, our theatre, and it has been rebuilt and added to over centuries. Its foundations, so they say, are in part Roman stones moved over from the city of Colchester after Boudicca had destroyed it, but I cannot say if this is true or only another story. When the Saxons conquered Norwich, the spot was made into a great beer hall; thus it stood a long time, and was the place where revellers would come and perform. In the sixteenth century our site was the White Swann Inn, and it was here that the Norwich Company of Comedians did gather and play. At first our theatre was religious, but then it shoved God off and became more and more secular. Increasingly it was about us mortal people and how we rise and fall and how sad we are and how happy and how brief.

In 1754 our neighbour, the Assembly House, was built. Here the well shod of Norwich came to dance and fall in love and have concerts and proper entertainment. At length that uprightness did spread out from the Assembly House until it infected the White Swann, and so at last, three years later, we became an actual theatre. The New Theatre we were called then, and our first show was TheWayoftheWorld