Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

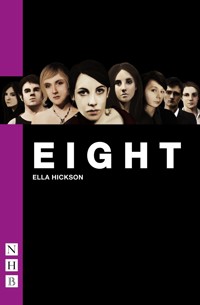

Eight compelling monologues offering a state-of-the-nation group portrait for the stage. From Millie, the jolly-hockey-sticks prostitute who mourns the loss of the good old British class system, to Miles, a 7/7 survivor, and Danny, an ex-squaddie who makes friends in morgues, Eight looks at what has happened to a generation that has grown up in a world where everything has become acceptable. Ella Hickson's play Eight was first staged at Bedlam Theatre, Edinburgh, during the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, in August 2008. It was awarded a Fringe First Award and the Carol Tambor 'Best of Edinburgh' Award. The production transferred to Performance Space 122, New York, as part of the COIL Festival, in January 2009, and then to Trafalgar Studios, London, in July 2009. In its original performances, each audience voted for four of the eight monologues that they wished to see, resulting in a different line-up at every performance. A ninth unperformed monologue is included in this edition. The monologues are ideal for performance by student and amateur groups; any number and any combination can be performed. They also provide excellent opportunities for actors looking for audition material.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 86

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

Premise

Original Production

Characters

Danny

Jude

André

Bobby

Mona

Miles

Millie

Astrid

Buttons

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Introduction

I created the characters of Eight in the hope of showing the effects, when taken to their extremes, of growing up in a world in which the central value system is based on an ethic of commercial, aesthetic and sexual excess. I, like my characters, am a twenty-something and have grown up in a world of plenty, unscathed by war or recession, a world defined by consumerist boom.

As far as I could see, the effect of such affluence was neither contentment nor discontent. It was, instead, wholesale apathy. In creating the characters of Eight I asked a group of twenty-somethings what they believed in – the almost unanimous answer was ‘not very much’.

Eight, then, when it was written, aimed to show a generation that had lost the faculty of faith. These eight characters are societal refugees – who are struggling to muster belief in themselves or the world around them. The result is either apathy or, perhaps perversely, fundamentalism. Faith is a human impulse; if there is no outlet for it in mainstream society it can become warped and misguided.

A year has passed since I wrote this play and much has changed. What was then a whisper of recession is now an undeniable reality. The students I was writing for and about had little idea about what the job market would look like by the time they tried to enter it the following September.

The next few years for recent graduates are going to be extremely tough – The Guardian recently announced that up to 40,000 of this year’s graduates will still be struggling to find work this September. Apathy is no longer going to be an option.

Whilst times will be hard – and I realise this may be easy to say when the worst is yet to come – I feel a little struggle may be no bad thing. For it’s only when times get really tough that you work out what really matters – and maybe, by then, we’ll be ready to believe in it.

Ella Hickson

July 2009

Premise

One of the central characteristics of the commercial world that Eight explores is ‘choice culture’. From channel-surfing to Catch-Up TV and X-Factor voting – we are a choosy bunch, we get what we want when we want it. Eight reflects this in its set-up.

When I directed the first production of the play, I offered the audience short character descriptions of all eight characters before the play began. I then asked them to vote for the four characters whom they wanted to see. As the audience entered the auditorium, all eight characters were lined up across the front of the stage – but only the four characters with the highest number of votes would perform. The other four characters would remain onstage, reminding the audience that in each choice we make we are also choosing to leave something behind.

Such a process is not essential for a performance of Eight and directors, of course, should remain in control of the line-up and order of play if they should so wish.

Eight was first performed at Bedlam Theatre, Edinburgh, during the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, on 2 August 2008, with the following cast:

DANNY

Henry Peters

JUDE

Simon Ginty

ANDRÉ

Michael Whitham

BOBBY

Holly McLay

MONA

Alice Bonifacio

MILES

Solomon Mousley

MILLIE

Ishbel McFarlane

ASTRID

Gwendolen von Einsiedel

Director

Ella Hickson

Stage Construction

David Larking

Technical Director

Xander Macmillan

The production transferred to Performance Space 122, New York, as part of the COIL Festival, on 6 January 2009, and Trafalgar Studios, London, on 6 July 2009.

Characters

DANNY, twenty-two

JUDE, eighteen

ANDRÉ, twenty-eight

BOBBY, twenty-two

MONA, eighteen

MILES, twenty-seven

MILLIE, thirty

ASTRID, twenty-four

(BUTTONS, mid-thirties)

DANNY

Danny is a well-built man in his early twenties. He sits on a black box in the centre of the stage with a corpse’s head lain across his knee, he is feeding water to the corpse. He is wearing jeans, a black wife-beater and black boots. Danny is twenty-two years old but he appears much younger; his learnt manner is one of faux aggression; however, he fails to disguise an underlying vulnerability. Danny is a little slow but essentially sweet.

Danny, hushed, talks to the corpse.

Here you go, little one – head up, ’ave some water, come on, your lips are all crackin’, come on. Look, I can’t be doin’ everyfing for you, it’s ’ard enough sneakin’ in for nights, that fat bastard porter is gunna see me one a these days and I’ll get fuckin’ nailed. Now come on, darlin’.

You’re a nightmare, int you? I used to be the same. Mum always said I was a pain in the neck, always bawling when she was tryin’ to get stuff done.

Danny walks forward and begins to address the audience.

Mum used to work for one of them poncey magazines; it’s why we had to move up north, to Preston; it’s newest city in England, you know? I was dead excited, shouldn’t have been. . . borin’ as fuck here. Mum’s job was to make sure all the people on the front cover of the magazine looked right. I used to watch her, it was like magic, she’d give ’em big old smiles and scrape off all their fat, anything not perfect she’d jus’ rub out, make it disappear. When she was done all them people looked beautiful, like, like – dolls. The problem was it made me sort a sad to look at all the ugly people after that; all them people who look fat or spotty or just sort a strange, when Mum made it seem real easy to look just right.

At school, Hutton Grammar, I was never bright so sports were always my thing, and I was always big, like my dad has been. They used to call him Monster Cox, which I always thought was cos he was built like a tank but it turned out it was cos he had a massive dick. He died in the Falklands, he was a Sapper, part a the Royal Engineers, had a bit more up top than me. (Laughs – self-deprecating.) Mum always seemed a bit afraid after Dad had gone, she seemed sort a smaller, she didn’t look ‘right’. I guess that was why I wanted to get big, like Dad had been, to make things better – protect her, like.

I was sort of keen on goin’ down the gym after school, cos it helped wiv rugby, and girls and that, so Mum, for my eighteenth birthday, bought me my first tub a protein shake, CNP Professional. At first it was just a hobby. I’d do, say, two hours after school, not much, like, reps of twelve – squats, crunches, lunges, flat-bench press, barbell curls – just the usual stuff. But it started feelin’ really good.

I was feeling better and lookin’ better, I can’t remember which one came first – they sort of seemed like the same fing after a while. So I upped my hours. And yeah, there was pain but I could ignore it – I was focused like crazy; I felt I could do anything. I was like one a Mum’s pictures, getting tighter and bigger and more and more perfect.

And soon it came. I could feel it. Sitting at the back of the classroom – I could feel my traps straining to get out a my school shirt, and all the girls were lookin’ too, they could see that I was different, they could see the strength, the fearlessness – my body was proof of the size a my balls. I didn’t need to be a hero, it was enough just to look like one.

But, but after a while people stopped lookin’, and it didn’t feel so good, it didn’t feel right. I was still getting a bit bigger but the change wasn’t as, as powerful as it was at the start so I started thinking all the same things again like why I didn’t have a girlfriend, what the fuck was I going to do with my life and what Mum was going to do all on her own if I went ’n, ’n. . . It was like down the gym I’d felt perfect, unstoppable, and then suddenly nothing was perfect any more.

My dad always said, ‘The more you sweat in training, the less you bleed in war.’ (Trying to be brave.) So I signed up, 4th Battalion, Duke a Lancaster’s Regiment, trainin’ every Tuesday down Kimberley Barracks. We were the new boys; they called us Lancs in 4th Battalion, the babies. Hauled in one day ’n pretty much shipped out the next – direct service to Basra, unsure whether you had a single or return, that’s what all the lads said. We didn’t have a fucking clue what we were doing, but I wasn’t bothered, I was there to fight – end of. I was pretty popular too; apparently it’s quite comforting to have your arse covered by a lad built like a brick shithouse.

His vulnerability dissolves a little – his face hardens, suddenly he seems older, tougher.

’Bout halfway through my tour, the day came, the older squaddies had always said it; one thing’ll happen, one day and you’ll never be the same. Mine came, 24th June 2007, it was my twenty-second birthday. We’re creepin’ into some sleepy suburb, the Warrior tanks were following us up. Tension was up, the drivers were spiked, chewin’ coffee granules ’til they dribbled black – but all was quiet – we were just having a nose about – (Stops, stares at the audience.) – I’m out front. (Snaps head round.) Suddenly, in bowls a fuckin’ Yank Humvee – (Danny jumps on top of the box.) – they’re chargin’ through, all shouting ‘GET SOME’, pelting out bullets like it’s a fuckin’ fairground ride. . . my lot hit the deck thinking Jonny Jihad’s out to play – (He jumps down and hauls the corpse up in front of him as if it were a rubble barricade.) – I’m squatting, low behind some rubble, waiting for the storm to pass when ‘Booooom!’. . . There’s smoke, I can hear screams but muffled, like, and. . . I’m down. (He falls to the floor, begins to drag himself back up onto the box, panting, frightened.

![Swive [Elizabeth] - Ella Hickson - E-Book](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/c1d36d5853ef1a1adbb527a05898ff1e/w200_u90.jpg)