Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Istros Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

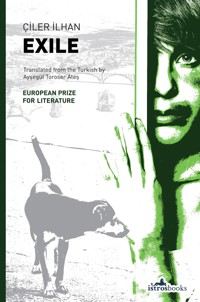

Exile is a collection of short stories with the taste of a novel. The over-riding theme is the sense of melancholy of those who have been alienated from their homeland, from their families or from society. By offering the reader short, vivid glimpses into other worlds; be they of real or fictional characters, Ilhan builds a patchwork of stories which highlight the lives of the dispossessed. As a woman writing in modern day Turkey, she is not afraid to take on the themes of honour killings or the American occupation of Iraq. All stories are open to her empathy and understanding. Born in 1972, Çiler İlhan worked as a hotelier, a freelance writer (Boğaziçi, Time Out İstanbul, etc.) and an editor (Chat, Travel+Leisure) at different periods of her life. İlhan, based in İstanbul, now works as the public relations manager of the Çırağan Palace Kempinski hotel. In 1993, she received a prestigious youth award for a short story. The award was a tribute to the memory of Yaşar Nabi, a leading publisher and writer. Ilhan's stories, essays, book reviews, travel articles and translations into Turkish have been published in a variety of journals and newspaper supplements.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 128

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ÇİLER İLHAN

EXILE

Translated from the Turkish by Ayşegül Toroser Ateş

For those exiled from their homes, their homelands, their bodies, and their souls...

in the hope that they may return to their homelands within.

English language edition first published by Istros Books London, United Kingdom www.istrosbooks.com

Originally published in Turkish as Sürgün, 2010

© Çiler İlhan, 2015

The right of Çiler İlhan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Translation © Ayşegül Toroser Ateş

Edited by Feyza Howell and S.D. Curtis

Cover design: Davor Pukljak, www.frontispis.hr

ISBN: 978-1-908236-25-8 (print edition)

ISBN: 978-1-908236-89-0 (eBook)

This project has been funded with support from the TEDA Programme of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Turkey.

EXILE

‘Exile is the unhealable rift forced between a human being and its native place, between the self and its true home: its essential sadness can never be surmounted.’

Edward Said1

1 Said, Edward. ‘The Mind of Winter,’ Harper’s Magazine, September 1984.

Zobar and Başa

It’s been so long since the drums and pipes fell silent in Hatice Sultan. Yesterday my Zobar and me, we went to take a look at our old neighbourhood. There’s no one left. Even Uncle Aziz has moved to Taşoluk... Zeynep, Gülfidan, Ertan Abi, every last one...

Aunt Emine had been the first one to leave. She moved to Izmir, to live with her daughter. Hers was the first house to be demolished. Then it was the turn of Gülbahar. Turned out onto the street in the middle of winter with two children, her house pulled down in the early hours, regardless of her tears.

Mustafa Abi turned out to be stubborn. He’s still in Neslişah with his wife and daughter, but the old coffee house’s closed down. Had he not owned his house he’d have been cooped up in Taşoluk a long time ago, like so many tenants. No one knows how long he’ll hold out. Some bloke or other comes over every day, asking him to sell his house.

Mother Milay and Coro moved to Edirne. When Mother Milay insisted she’d never live in Taşoluk, they took Yilo, Lola and the grave of Dobru and moved early one mornin’. I cried buckets over them. After all, we’d come to know them as our mother and father ever since I was five and Zobar seven. They’d taken care of us ever since they snatched us out of the clutch of the Grim Reaper back in Romania, so how could I not cry? My sweet Tinke kept licking my tears as I cried... ‘Come with us, we won’t move if you don’t come with us,’ they said; especially Mother Milay who insisted we go, pleading for days – ‘don’t make me leave my heart back here’ – but we didn’t want to. We liked Istanbul; ‘besides, we’ve grown up, we can look after ourselves,’ we said.

Soon, my Zobar, Cingo, Tinke and me, the whole gang, we’re gonna collect paper. In Taksim. We’ve been going up to Taksim ever since we moved to Dolapdere. But because I had a miscarriage, I can’t walk far. That’s how things are for now: It occurred to me afterwards that Mother Milay knew I was pregnant when we got married, ‘Are you pregnant or what, girl?’ she’d asked, but I’d paid no attention: She doesn’t miss a trick, does she?

Thank God the weather is fine. Cingo’s not fussed but Tinke’s over the moon. Her tail goes pat, pat, pat non-stop now she’s seen the sun.

My Zobar’s been so absent-minded ever since we moved here. He doesn’t talk much, but he’s been eating his heart out, I know. He dug his heels in so we wouldn’t leave the neighbourhood, you know – ‘we’ll find a way to stay,’ he’d said to me, so he’s tried everything he could lately just so he could keep his word. You crazy boy, did you really think I’d keep my hopes up just because you said so? How were we to stay when the landlord had already sold our house? All the neighbourhood had taken off; how could we have stayed? Don’t I miss my house in Hatice Sultan too? Don’t I just? In fact, from time to time, I can’t help but cry. That’s when my Zobar takes me into his huge arms and says, ‘Don’t cry my beautiful Başa, we’ll go back to our Sulukule some day, we will for sure, you’ll see.’ But I know: Sulukule now belongs to others.

This morning, I realized that crying’s no help either. I whispered in my Zobar’s ear ‘Come, almond eyes, let ourselves be our homeland.’

CRIME

Iraq II

By the time the Americans came to Iraq, I’d long given up hope for both Iraq and for that scum who called himself a ‘father’. I was pleased. Pleased that piece of filth might finally get his just desserts. My sister Rana and I never got over the pain of losing our husbands.

Stupid me! Just goes to show I still hadn’t learnt my lesson after having seen so much wickedness even from my closest. Just goes to show I’d failed to understand how power makes the sons of Adam lose their humanity, turns them into demons. Just goes to show I’d failed even to imagine how ruthless foreigners would some day give birth to the demons within, how they would take to the streets and feast endlessly on these lands, these holy lands where civilisations once took root. It just goes to show that I didn’t realize that the soldiers who would go for their bullets, making no exception for children, and who would go for their zips, with no respect for mothers or daughters, would cast their humanity off and become possessed. It just goes to show that I failed to envisage that my Iraq would from then on live by night, by night alone, as if now located at the poles, where the sun would never again be able to extend its fragile visage over daybreak.

And that boy from Karbala, whose big brother was taken away in a night raid; I dream of him every night; his pupils dilated, behind his mother with his kid brother, leaning against the wall. As if the wall would help him. He is shivering like a leaf in his pyjamas, but the screams are the mother’s, crying for her elder son, who was taken from his house in the middle of the night to be carried first to torture and then to his death; what falls to his share is the silence of a grave. That dark-eyed boy in the newspaper who harbours in his eyes the sorrow of the world, the anxiety of the world. His picture won’t leave my desk; nor his face my dreams. Oh my mighty Mesopotamia! Oh how they have hurt you.

Ball

We were playing ball. There was our Sülo, there was Mehmet, there was Fedai, there was Ramazan, and there was Raşit. There was my big brother and Raşit’s big brother. That’s where we always play ball. Sülo’s team was winning again; doesn’t he just love himself as he sneaks past! At that moment, I saw my brother and Raşit’s brother wink at each other. I turned my head and looked; the gendarmes. I didn’t pay any attention. They always come and take our ball when we’re playing. We’re used to it now. They’d taken my big brother and Raşit’s to the station a couple of times and had beaten the living daylight out of them. They were forever accusing them of aiding the rebels, but they never do. Dad always kept us out of these conflicts. He’d promised mum before she died.

I thought the soldiers were going to take our ball again. But suddenly they started shooting. I saw my big brother on the ground. Five soldiers had surrounded him and were firing around his body. My brother had wrapped his arms tightly around his head. I tried to stop the soldiers. One of them punched me in the face and felled me. My brother tried to get up but they pushed him down. Then they started kicking him. Then they dragged him off into the minibus. They kept kicking him as they dragged him. I saw Mehmet running towards the village and I yelled after him, ‘tell my father, tell him to get to the station immediately’. I started to run. The minibus speeded up. I ran all the way to the station. It’s not far from where we play ball. They didn’t let me in. I waited – then Dad came. They didn’t let him in either. Ten minutes later the gendarme came over. Your son’s heart has failed, must have had a heart condition, he told Dad. It’s a lie. My brother was fit as a fiddle.

I’m a Bastard!

I’m a bastard! Literally a bastard! God, did I have to see my picture in the paper to realize this? The picture where I’m gagging that young girl? Newspapers said she was eighteen or twenty but she wasn’t even seventeen! After she saw the photograph in the newspaper my wife rang the station and yelled at me, ‘You’re a bastard!’ She said she was ashamed of me. I’m ashamed of myself too.

I just didn’t think. My Boss had given us all strict instructions,‘Be on your guard during the Tunceli trip of Our Esteemed Minister, or I’ll have you all!... Grab anyone that speaks, that squeaks, that stirs, that budges, or does anything at all and drag’em away!’ he said. Then, when that girl suddenly cried ‘Our Esteemed Minister!’ while Our Esteemed Minister was speaking – and it was just my bleeding luck, I was right next to her, wasn’t I – and I never thought, just shoved both hands over her mouth. And not just her mouth, either, I saw later in that photograph in the newspapers: I’d smothered her – her nose, her eyes – and she wore glasses too, and I grabbed them off in a rage! My mouth pursed in rage as if I’d kill her. And bugger it if our Inspector hadn’t also heard her shouting ‘Our Esteemed Minister!’ and turned up right beside me ordering ‘run her in straight away!’ Chuffed to bits I was doing a great job, I was in his good books, you know, I dragged her away and stuffed her into the patrol car. Mind you, I was still proud of myself. Who could say she wasn’t a separatist?

She started crying inside the car. I didn’t give a damn. I was saying to myself, this little bitch will give us a couple of names now, who knows, we might even corner those responsible for yesterday’s attack. How that would please my Boss! I’ll boast about it to my wife.

We slammed her into a cell at once. Naturally, I joined the interview too; well, we caught her, we’ll make her talk. She’s in custody at the most infamous station, I was saying to myself, she has no choice but to spill the beans. And I’ll become the pride of the station. Boy, was I proud of myself. An hour, two, three – not a word. She was crying buckets. ‘I’m not a separatist or anything, all I wanted was to say to Our Esteemed Minister, “my family is not letting me go to university, please help me.”’ ‘Look here,’ I said firstly, ‘pull the other one, you little bitch, it’s got bells on.’ So Ahmet and me, we tried all the tricks we knew: Anything, you name it but still, nothing.

Then someone pulled strings and we had to let her go after six hours. Without getting a word out of her. Yet at home I was still telling myself that there was definitely something fishy about this girl.

Dear God! Never realized how innocent her little face was! I never realized until I saw it in the newspaper.

You Killed

You killed my mother. You killed my father: My uncles and my aunts. You killed my grandmother and my grandfather: My cousins, their wives: My father’s sisters, their husbands. You killed me within.

You killed my beloved, my husband, my love. You killed love.

You killed the flower within me.

You dried up the rain. You drained the water. I’m dried up.

You rooted out the tree of life our orphaned arms had nourished within us.

You cut the climbers we’d raised under each other’s light, each other’s shadow.

You destroyed the road along which we could never have walked without being united.

My days, my nights.

You imprisoned my breath.

You sewed my lips together.

My nails no longer grow.

You froze the lakes. You froze my blood.

My joy, my hope.

You froze me within.

You sucked out my soul.

You stole my old age.

My cheeks.

My cheeks hurt.

What has my Hrant2 done to you?

You killed. You killed me too.

2 Hrank Dink, a Turkish-Armenian journalist assassinated on 19 January 2007

Batman

‘Why do so many women commit suicide in Batman?’ they ask.

There is nothing we can add to life, other than death.

We are invisible at home and in the street. Like an old piece of rag that cleans the floors, the windows, the doors. We are put to all sorts of work. Life becomes even more unbearable once we start to blossom, once we are fragrant. Bored with our mothers, whose breasts have sagged, whose flesh has lost their firmness from giving birth a dozen times, the gazes of our fathers alight on our newly budding breasts. Suddenly our mothers go blind, our brothers deaf.

‘Why do so many women commit suicide in Batman?’ they ask.

There is nothing you can add to our life, other than death.

When we grow a little older we are married into other families. But we are found not to be virgins, for we are not. And in the morning of that very same night, we are dumped back in front of our fathers’ doors like milk that has gone sour. What a calamity! The dirty linen could not be kept secret, the true colours are revealed; the world is set ablaze. A scapegoat from among the destitute, the poorest wretch in the village is used to restore the family honour; this dog deflowered my lovely daughter on this and this date, before she could give herself to her husband, he is to be blamed! Yet words don’t suffice to clear the honour of a family. Someone must be hurt, blood must be shed. So that all should believe that the house the girl came from is immaculate.

The family elders speak: The boy who deflowered our girl on this and this date has a sister – doesn’t matter that she’s eleven or twelve, she’s a woman – we will deflower her.

One morning, as she’s out fetching water from the well, the wretch’s sister is held down and raped, with the help of the female relatives if necessary (what is there to be surprised at, after a point there’s no telling what’s right and what’s wrong) – so that everything fits into place. So that the father of the deflowered girl can brag: Mehmet, we know your son deflowered my daughter on this and this date, my honour has been avenged, we have deflowered your girl in return. We’re even.

‘Why do so many women commit suicide in Batman?’ they ask.

Instead, you should ask: Is a man’s blood sweeter than that of a woman?