7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

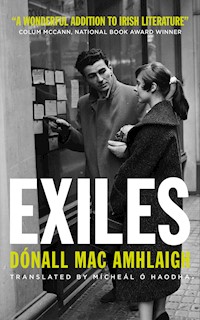

Two Irish migrants on the cusp of new lives in post-war Britain. Two young people who dare to dream of a better life, and dance the music of survival in their adopted homeland. Afraid that his wife and children will arrive over any day, Trevor is in a hurry to settle old scores with his rivals and to prove himself the top fighting man within his London-Irish community of drinkers and navvies while Nano seeks to escape the stifling conformity and petty jealousies of her peers and forget her failed love-match at home. Will Trevor finally prove himself "the man" and secure the respect that he feels is his by virtue of blood and tribe? Does Nano have it in her to break free of the suffocating bonds of home and community and find love with Lithuanian beau Julius? Written at a time when the Irish were "building England up and tearing it down again," and teeming with the raucous energy of post-war Kilburn, Cricklewood and Camden Town this novel is one of the very few authentic portrayals of working-class life in modern Irish literature.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Praise for Exiles

‘A hunger for the possibility of freedom. The tumbling of borders and convention. The migrants of Mac Amhlaigh’s Exiles fear the loss of home and its fixed reference points. Their voices swerve between two languages, two cultures, and two different ways of existing between the future and the past. A wonderful addition to Irish literature.’

Colum McCann, National Book Award winner with Let the Great World Spin.

‘Donall Mac Amhlaigh made a vitally important contribution to the literature of the Irish in Britain and indeed to the Irish diaspora worldwide. As with many working-class writers of his generation and writers of minority languages in particular, he didn’t receive the recognition he deserved while alive. Mac Amhlaigh’s Exiles demonstrates what the Irish and the migrant peoples of our day have always known – to be truly at home is not necessarily to sleep beneath a familiar roof. Home is not a particular place but is a community or a people and their sense of identity. I cannot stress strongly enough the importance of bringing this work to a wider readership.

Tony Murray, Director, Irish Studies Centre, London Metropolitan University and author of London Irish Fictions: Narrative Diaspora and Identity

‘Donall Mac Amhlaigh is the most perceptive and informed writer on the Irish in twentieth-century Britain. Mícheál Ó hAodha is to be iiicongratulated for making this masterpiece… available to an English-reading audience. It deserves a wide readership to remind us what emigration and exile was like for the generation who left Ireland in the 1940s and 1950s.’

Professor Enda Delaney, author of The Irish in Post-War Britain

‘Mac Amhlaigh’s novels and books have been rightly-praised for their exploration of the harsh lives of Irishmen who laboured to build up Britain again after the devastation of the two world wars. No less an achievement however, is his searing account of the lives and conditions of Irish women emigrants to Britain. Mac Amhlaigh’s intimate evocation of the inner-most thoughts and aspirations of Nano Mháire Choilm, the novel’s central female character, is on par with the masterful portrayals of this generation of Irish working-class women and their hopes and dreams by another great Irish writer, Máirtín Ó Cadhain.’

Máirín Seoighe, documentary-maker and producer of the series Imircigh Ban (Women Emigrants), 2015

‘Despite the massive Irish emigration to the cities of England it is an experience little explored in literature. But Donall Mac Amhlaigh was its great chronicler. He was the best man for the job as he both lived the life and imagined that of his colleagues. This great novel is his best achievement, richly translated for the first time. It captures those times of hardship, of fun, of love and of spite perfectly, when the Irish were ‘building up and tearing England down’. It is a story which appears to be documentary but is truly a sympathetic recreation through the imagination of what it was like for those hundreds of thousands of Irish who left our shores.’

Professor Alan Titley, translator, The Dirty Dust (M Ó Cadhain), Yale University Press

iv‘A valuable service [has been done by] Mícheál Ó hAodha… for the Irish Studies community worldwide, and especially for those of us who work on Irish immigrant culture in Britain. Although widely recognised as a classic of modern Irish-language fiction… [Exiles had remained] off limits to most Anglophone scholars because it [was] not available in English translation. In rectifying this discrepancy, [the translator] has produced a literary text worthy of the original, which deserves a wide readership not just nationally but globally.’

Dr Liam Harte, Senior Lecturer, in Irish and Modern Literature, The University of Manchester and author of The Literature of the Irish in Britain: Autobiography and Memoir, 1725–2001

We have very few published first-hand accounts of the life of the Irish navvy and worthwhile works of fiction by authors who knew whereof they spoke, are as rare as hen’s teeth. The books of Patrick MacGill, JM O’Neill, and Donal Mac Amhlaigh spring to mind. Mac Amhlaigh’s novel, [Exiles], written in his declining years, has until now been inaccessible to readers unable to read work in the Irish language. It is greatly to his credit that Mícheál Ó hAodha has performed this labour of love… it [should] be enthusiastically received, not only by scholars of Irish migration history, but also by that general readership which undoubtedly exists for authentic artistic insights into that now-vanished world.’

Ultan Cowley,The Men Who Built Britain: A History of the Irish Navvy

Exiles

Dónall Mac Amhlaigh

Translated from the Irish by Mícheál Ó hAodha

Dedicated to all my relatives in Leeds and Liverpool and the Irish who took the boat across the water.Mícheál

Contents

Chapter 1

On his way down to his train at Galway station, former soldier Niall O’Connell turned into the Philadelphia bar at the corner of Eyre Square. He set down his case and opened the packet of twelve Afton cigarettes he’d bought up in Renmore earlier. He had a good look around as the barman pulled his pint and took it all in – the baggage that most of the other customers had brought with them, the ancient advertisements for drink and tobacco, the rows of bottles that lined the shelves and radiated the wan, lonely light of the autumn sun, the damp, rust-coloured sawdust, cigarette-butts and ugly gobs of spit that littered the floor. It was more than three months since Niall O’Connell last stood in a pub.

Just as stupid an idea of ordering a drink was going back on the fags now, not that abstaining from them for a few months had diminished his love of them in any way. He had still been in two minds when he’d bought this packet in the canteen earlier. He wasn’t sure whether he should smoke them at all – or, at least that’s what he’d told himself, anyway! Truth is, they’d just been lying there in his pocket, secretly calling to him all the time, the same as a child promised a bag of sweets. The reason for him having given them up had gone, in any case: from now on, he could afford his own cigarettes and drink. Today was a significant day in his life. He could feel it. And it was a time for celebration. Still, his joy at returning his soldier’s kit to the stores for the last time early that morning had been tinged with regret. Saying goodbye to the army forever and having the big iron gates of the barracks 1clanging shut behind him, a strange feeling had come over him, that of an old prisoner suddenly released after years in jail. A wave of sadness had coursed through Niall and a lump had formed in his throat.

He grabbed his pint and backed away from the counter, away from the other travellers who were pushing forward now and ordering drinks, left, right and centre. The two barmen were under pressure, flicking the tops off beer bottles and dishing out pints as quickly as they could. He couldn’t remember seeing the Philly bar this crowded before, unless it was for the Galway Races. All the people in there were from Connemara: all speaking Irish, Irish, Irish. That sweet, melodious Irish that was music to Niall’s ears; he’d miss it now that he was leaving Galway, as surely as he’d miss the army itself. Even downtown earlier, when he’d done a quick trot as far as the bridge, he’d been surprised at the huge crowds of Irish speakers – almost all of them on their way to England, no doubt. Not that there was anything unusual in the people of Connemara and the Aran Islands heading across the water. After all, that was where all his army comrades had gone once they’d completed their term in the army. But on this Saturday, in the autumn of 1950, you’d have been forgiven for thinking that the entire population of the Gaeltacht was migrating, lock, stock and barrel, over to England. Because the Connemara people were everywhere: congregated in groups on street corners, in the doorways of the shops or standing out in the middle of the path, unwittingly impeding the other passers-by. They were typical country people in town for the day – meeting up and chatting, and everyone friendly and relaxed. This crowd was a mixture, some of them shy and inoffensive: like fish out of water now that they were in the city. Others still had a real lively energy about them – as if they couldn’t wait to go abroad. The majority were young people, men whom you could tell were powerful workers and swarthy-skinned girls – bright eyed and pretty – the type of girl whom Niall O’Connell had always found really attractive. It was really sad that so many young people had to emigrate like this, Connemara 2people especially. It was a disaster, Niall thought; of all the classes of people to be leaving the country! After all, this tribe of people were the real rightful heirs to the Irish nation! If there were any justice in the world….

If Niall had been running the country, he’d have tried his level best to keep these people at home – for the sake of the Irish language, as much as anything else. What was the point of all that talk they’d heard about independence – that blather about language and nation – if they were just going to let the wellspring of Irish culture disappear like this: thousands of people leaving forever on the immigrant boat! This was more than a catastrophe! It was a form of treachery to the ideals of the heroes of 1916 and the generations who’d come before them.

People were lashing into the drink heavily now, steeling themselves for the journey ahead. A few were already well-on-it and full of talk and bravado. Men leaned in on one another’s shoulders in that familiar fashion of the country people when they came together for a drinking session. That tribal camraderie that combined clannishness with a veiled sense of threat. This race of people were a strange breed in the way their loyalty to one another could transform itself in an instant and break into argument: it was love/hate as two sides of the same coin. This was a peculiarly Gaelic trait Niall understood because he knew these people intimately, and recognised their ways. His connection to them resonated at his core. Their ways were his ways. Most of all, he loved their authenticity, the sense of humanity that defined them and was rooted in their language. And if he’d been able, he’d have memorised and recorded every single word and gesture of these people; he’d have transformed himself into some kind of a recording machine for these Irish-speakers and their culture, and salvaged their memory as best he could. Theirs was a unique culture, one that they’d somehow managed to salvage from ancient times; kept with them through the toughest of ordeals. Their history was important. Their story deserved to be told. 3

To the left of Niall was a middle-aged man was who drunk and ready to sing – if anyone’d listen to him, that is! The man suddenly threw his head back and shut his eyes, then began working his hands, winding himself up to reach for the words of his song. He was ready to sing and yet he was on-edge. He’d a prickly look about him – it wouldn’t take much to start an argument with him.

‘Neós, an chéad lá den mhí is den Fhómhar, sea chrochamar na seólta….’

‘Well… now, on the first day of September, we hoisted our sails,’, he sang at the top of his voice, as if daring anyone to interrupt him….

‘Nár laga Dia thú!’ (May God never weaken you) someone called out in a mocking voice and a few men looked over in disgust at him, much as to say that they resented this old-fashioned carry-on of his. These latter men were the types who’d already spent a season or two working over in England, Niall suspected, because they were the types who’d little patience with the latest wave of emigrants – such as this singer – whom Niall suspected was probably leaving home for the first time. The singer stopped suddenly and glanced around the room. His eyes settled on Niall and stared at him as if taking him in properly for the first time. He swayed drunkenly but the next moment assumed a confrontational pose, as if to challenge this unwelcome intruder to the proceeding

‘Up Muicineach!’ the man shouted out in challenge.

‘Up Down!’ Niall replied and someone skittered with laughter. Niall regretted his retort immediately. He knew how easily such smart-alec comments could start a row in a pub, and he’d never been fond of arguing or fighting. The man gave Niall another dizzy stare but then his attention shifted away. He began to whistle a reel. He’d an urge to dance now and so he drew his arms to his sides, pushed his two thumbs out in front of him and directed his eyes to a point somewhere at the far end of the room. Then he launched himself forward 4drunkenly. Niall backed out of his way and tried to attune his ears to the conversations that were going on around him. What he heard disheartened him, however. All the talk related to England and to what life was like across the water. These people had already left Ireland behind in their minds….

No, you f**r, you change in Birmingham, you’ve no business going to Rugby…. On the beet son, to Peterborough. That’s where loads of the Mayo crowd go, those hoors are going there for years. And I don’t need to tell you, Bartley, you’re way better off with an English contractor. McAlpine or Wimpey or one of them. Let the Irish ones go to hell, those b**ds would kill you with work…. Yep, the hoors, they were getting two pounds a day, seven days a week . Government work, son….

Wasn’t Niall lucky that he’d been thinking ahead and saving for this day – so that he didn’t have to leave like these lot here?! That would be his absolute last resort. He’d prefer to stay in an army uniform for the rest of his life than have to leave Ireland forever and be reliant on the English for his livelihood

He must have some good stuff in him all the same, seeing as his plans had worked out and he’d managed to put a small bit of money aside lately. I mean, there were plenty of distractions that he could’ve blown it on, no bother. Hadn’t Captain Delaney referred to him as ‘the entrepreneur’ – taking the piss out him? He was jealous because he knew that Niall was putting his weekly wages aside and saving it, whereas Delaney didn’t have it in him to save a single penny! Every Wednesday, Niall had left a full two pounds of his wages sitting in the book and used the remainder to get him through the week. This had been no mean feat when you saw your comrades heading down to town of a night and having good craic while you were left hanging around the barracks, stretched out on your narrow bed and staring at the ceiling. It had been tough to hold out, but Niall had managed it 5despite everything. That’s not to say that he hadn’t often been sorely tempted to give up and head out on the lash…. There’d been plenty of evenings when he’d been a right cranky b**ix because he was so sick to the teeth of staying in; he’d been at the end of his tether often enough: that desperate for even one pint of the black stuff. Never mind all the times he’d been dying for a smoke! He’d stuck to his plan all the same, and as the day of his release came closer, the temptation to break his strict regime had lessened and he’d sensed victory. And signs of it now – he’d a nice little stash of money set aside for himself. And he wasn’t dependent for his money on anyone else – whether Irish or English – unlike this poor legion of the dispossessed here now, all of whom had had no option but to leave home so’s they could earn a bit for themselves. Paddy Delaney could say whatever he wanted about him – but the joke was on him now!

Niall finished his drink and glanced up at the Fallers clock above the bar. He’d time for another drink. He didn’t need to be at the station yet. Now that he’d the sweet taste of porter on his lips again he couldn’t believe how he’d managed to stay off the drink as long as he had; he’d never have believed he had that much willpower in him. And as for the fags! The tobacco smoke worked its way down through him now in a wave of pleasure. It was just beautiful. Niall slammed his glass down on the counter and called another pint. He felt slightly dizzy now – between the cigarettes and the drink – but it was a nice dizzy, like a little dance of joy up and down his body. The crowd was pressing in on the bar and Niall backed out of the way, pint in hand. He was surrounded by people that would have stood out in any company. Even the way they dressed was distinctive – never mind their language and mannerisms. They had a wild half-subdued energy, something that distinguished them completely from people of other Irish regions. It was this same energy and dynamism that stood them in good stead over on the plains of England, where they tore into the work with great energy – eager to prove themselves. History and resilience was 6inscribed onto these faces of the west of Ireland. It was part of their Gaelic inheritance and make-up, and was passed on through generations. The men here were all style in their suits made to measure by the lame tailor down at the Long Wall, even if shop-suits were taking over in other parts of Ireland. Strangely enough, what was in for these lads was whatever fashion was on the wane elsewhere: the wide trousers, the long collars, the draped-shoulders look; and that wasn’t counting all the other showy details – side-folds, big glitzy rings, multi-coloured ties, high-necked jumpers and zips. Many of them still wore caps even though that was going out of fashion with the younger crowd. Some of the lads sported a fountain pen or a comb in their jacket pocket, a flourish that the east Galway people would have regarded as showy or effeminate!

Niall himself wore a tweed suit and proudly sported a fáinne. After all, it was up to Irish people to buy their own home-produced products, he believed, and wasn’t this as good an example of patriotism as any? Not that it was attracting too much attention right now! A little shiver of loneliness went through him once more. It’d have been nice had even one of the soldiers from the barracks – or indeed anyone he knew – happened to call in for a bit of a chat. All this, and the fact that he wouldn’t get much chance to speak Irish from now on, made the years before him seem a humdrum prospect.

Niall looked around to where a young woman was sitting by herself next to the door, anxiously fingering her marriage ring, turning it around as if it might give her some insight. Judging by the loving glances she was throwing in his direction, it was her husband that was standing in front of her. He was swarthy and hawk eyed, a strapping young fellow who held himself ramrod straight. Handsome, with high cheekbones and piercing green eyes, this man sported a chequered cap perched rakishly on his head and a tie that was secured so tightly it looked like it’d choke him. He was as fine-looking a man as any in the Philadelphia bar that day, a true Westerner if ever there was one. A 7thick ring made from the corner-piece of a three-pence coin adorned his right hand, and around his wrist was a strip of leather…. Here is one of the rightest, hardest men as ever there was, Niall said to himself in a respectful tone. But for the amount of attention your man was paying his wife, she might as well have been a hundred miles away! That he was already three sheets to the wind was clear from the heat of the debate he was engaged in with two other sturdy looking bucks. Both of these sported blue gabardine coats and caps, the peaks of which they’d pulled backwards, as if to somehow make themselves look neater or more compact. The men were discussing some feud about seaweed that a gang called the Whites had taken over with them to England, a feud that was so bitter now, someone could be killed. The fellow that had red hair was going on about the fighting prowess of some man called Pete Willie, while the other two were contradicting him.

‘Orah, God grant you luck,’ he said to the others. Even the best of the Whites wouldn’t last two seconds with Pete Willie, not two seconds, I’m telling you!’

‘By Jaysus, but you might be wrong there, Trevor. Colm Pats White is some man – I’m telling you now!’

‘Even if he’s good, Peteen has a punch on him that’d knock a horse – sure, they say he gave Thornton himself plenty of it back in Doire Nia one day there a while back?’

‘So they say.’

‘That’s what I heard, Coimín!’

‘I find that hard to believe,’ said the third man.

‘There’s two sides to every story.’

‘There is, and seven sides! Any of the Whites would match Pete Willie, I’m not saying Máirtín Thornton.’

‘I’m telling you now, Trevor, boy, there’s action in that crowd you don’t get in many.’

‘And, damn it all sure? Did I say that there was no action in them?! 8There’s action in them alright but sure, plenty of men have action in them – that’s not to say that any of them’d be able for Pete Willie.’

There wasn’t much in the way of a hankering for home amongst these lads, anyway; if that’s all that was bothering them now that they were leaving their native country! They were like a people that were blind to their own fate, Niall thought. And if that poor woman who looked like she was about to burst into tears was the big red-haired fellow’s wife – and sure enough, she was – how come your man wouldn’t spend his last few minutes with her now, instead of arguing like this about a crowd of idiots who were feuding with one another?

The same thought crossed Niall’s mind again up at the train station later on when he watched the same man saying goodbye to his wife. She was weeping in a heartbroken manner by then and, once the engine roared to life, she snuggled herself into him and held onto him as if she’d never let go. This display of emotion on the part of his wife embarrassed the man more than anything else because he shoved her roughly to one side and hopped onto the train. She wasn’t the only woman that was crying now, either, because everywhere you looked there were young women and their families in tears. One elderly man stood alone next to the edge of the platform and wiped his eyes with the corner of his bright Sunday bawneen as he shed copious tears. A young girl leaned her face against the carriage window, all the sadness of the world in her big tear-stained eyes. The same girl wound her handkerchief endlessly around her fingers as if she could squeeze her sorrow away in its folds. The sound of a woman’s laughter came from one of the carriages just then, a laughter that was the other side of tears. The people tried their best to blot out the sadness of the moment. Crowding onto the train were pensive-looking men who’d left their women and children behind them earlier that morning back west, men who’d tasted the bitter cup of necessity and would have given anything not to leave home or family behind – if they’d only had a choice in the matter. Other men who were in a different mood took 9their seats now, fellows who were well-on-it already and whose sole concern now was dominating one another in conversation. The latter were the lucky ones, in a way, Niall O’Connell thought: emigration didn’t bother them. And maybe they’d the right idea, really, seeing as they had to leave the country anyway. There wasn’t really much point in getting down and mournful about it, was there? That’s the way they saw it. Of course, Niall himself would’ve been making the same journey if it hadn’t been for the plans he’d put in place already. The truth was that there were better men than him now left idle and unemployed in every town in Ireland and there was no sign of the situation improving.

Niall boarded the train and took his seat in the same carriage as the big red-haired man and his two friends. Opposite him sat a dark, russet-haired girl who was travelling alone. The big man chatted away loudly with his friends, still oblivious to his wife who stood outside on the platform, her eyes glued to her husband as if absorbing this last sight of him with every fibre of her being. Two young girls – sisters, by the looks of them, tucked themselves next to the group of men, and began a conversation with a solid-looking young fellow with black sideburns and a gold wrist-watch. The sisters had black curly hair and hazel eyes. They were no more than seventeen- or eighteen-years old. A small streak of dust marked the corner of one girl’s eye – she’d been crying earlier. She’d recovered, however, judging by the way she was flirting with the buck with the sideburns. Niall had never found it easy to make casual conversation like this; he envied how easy conversation came to them.

It was a mortal sin, he thought, that such beautiful girls were being taken away across the water to a place where no-one would understand how unique and special they were. If the people running the country had been doing their national duty they’d have tried to keep all these people at home. The youngest of the sisters gave a heavy sigh as the train juddered and slipped slowly out of the station. A silence fell over 10the company. The big man looked over at his wife and signalled vaguely in her direction. He wasn’t too bothered, by the looks of things. It was different for Niall. A shiver of loneliness coursed through him and the train gave a hollow echo as they clattered over the boards of Lough Atalia bridge. He stared fondly out over the blue tract of water and at Moneenageisha on the northern side, and then the fortress-like walls of Renmore Barracks. Over to the south the shoreline was dotted with the small blue-coloured thatched houses of Ballyloughane and the smaller villages round about, villages Niall’d come to love over the previous three years – Ardfry, Tamhain, and further on down to Kinvara and Ballyvaughan. Even though Niall was leaving Galway for a new stage in his life, the loneliness went through him in that moment like a cold wind. There was nowhere in the world that he loved more than Galway.

Once they’d passed Athenry, Niall felt a certain estrangement from the countryside. He was distracted by the russet-haired girl that sat opposite him, too. She was very pretty, he thought, a woman that it would’ve been easy to fall for; she was the type he’d have fancied himself – unless she was going out with someone else already…. The girl stared dead-eyed out the window as if intent on avoiding conversation with the other passengers. Every now and then however, she gave a flicker of a smile despite herself as she listened in on the conversation of the others. One of the gabardine coat brigade tried to make his way out into the aisle, giving Niall the chance to talk to her. He lifted her case onto the baggage-rack overhead and she thanked him politely. She told Niall that she was headed for a town called Norwold, a place that wasn’t too far away from London, from what she could tell. She’d got a job in a hospital there and she was going to give it a go and see how she got on. It was only recently that she’d decided to leave Ireland. It wasn’t that she’d any great hankering for England, she said, with a certain tinge of regret. There was a bit of a story behind this girl – she was someone who was emigrating almost 11against her will, Niall could tell. As if in recompense for this information, he told her that he was heading home to Kilkenny. He’d just completed his term-of-duty as a soldier in An Chéad Chath, the Irish-speaking battalion. Had he a job lined up back home, she asked Niall, and he told her about how he and Butler had plans to go into business together, something that’d keep the wolf from the door, God willing.

It was Kieran Butler, to give him his due, who’d ensured Niall hadn’t gone off the rails, as Niall had been a bit wayward prior to this. They had been schoolmates – for as long as they’d stayed at school that is – and it was when Niall was home on leave in early-summer that they’d decided to go into partnership. Kieran had a job in the city graveyard. It wasn’t the worse job in the world by any means, but – as Kieran’d say for a laugh – you’d be long enough there when you were dead – never mind spending all your days there when you were alive as well! There had to be other ways of making a living, he said, ones that didn’t involve being under someone else’s thumb all the time. You’d never get ahead in this life if you were always reliant on others for your weekly wage. It was lack of capital that was the biggest barrier to getting ahead, Kieran said. You just had to have a small bit to get off the ground first. If you had a bit of go in you and weren’t afraid to take a chance….

Something had stirred in Niall as they’d chatted that afternoon in Bridge House, looking out over the river Nore, Kilkenny Castle and all the new-shorn trees. There and then, he’d decided to come home again and give it a go….

Kieran’s plan was simple – put a small bit of money together and buy a horse-and-cart and timber cutting equipment, a two-handled saw, an axe and a wedge – and begin selling firewood around the town. Trees were cheap to buy, Kieran said. There were farmers around the place who’d as good as pay you to clear away fallen trees from their land and he’d a fair idea where they could get a horse and cart fairly 12cheaply too. ‘The brave man never lost it,’ said Butler, and – wasn’t this the truth? – nothing ventured nothing gained. Two hours later and the deal was done. They’d save as much money as they could in the meantime – waiting until Niall was finished with the army – then they’d get going properly with the business. You had to start somewhere, and seeing as they were at the bottom, there was only one way they could go… and that was up. Anyway, who’d heard of a soldier or a graveyard worker who made big money?

Their plan made good sense, the russet-haired girl told Niall, and she wished him all the best with his new business. Anything was better than just going with the flow. It was up to everyone to find their own niche in life….

Definitely – there was something eating this girl, Niall thought. And she wasn’t long divulging it to him, either. She was going out with a local lad back home and she mightn’t stay too long across the water because of this. She’d see how things went…. Life was strange and you never knew what kind of turn it might take. Just when you thought things couldn’t get any worse for you, there’s be a sudden turn up for the books – or, at least, that’s what the older people always said!

That other fellow must have been mad, Niall thought, because if he’d been going out with a lovely girl like her, there’s no chance that he’d have let her slip through his fingers and disappear off to England like this; no more than he’d let Peg Dineen slip from him either, if he thought that he was still in with a chance there…. Sure, wasn’t Peg one of the main reasons that he’d returned home in the first place – if she’d only realised it? Just thinking about her now sent a dart of longing coursing through Niall. Butler had already started working on the business. He’d bought a nice quiet-tempered pony already, as well as all the tackle and accoutrements; it wouldn’t be long as Kieran had said in his last letter before they had their own yard and a big sign high-up over the gate: O’Connell and Butler, Fuel Merchants. Niall reached across and offered the girl a cigarette but she politely refused. 13She never bothered with them, she told him. The two sisters didn’t smoke either, by the looks of it. They were chatting away now to the black-haired lad with the watch, and the gabardine-coat men. Everyone at their ease with one another now. The sisters were heading for Huddersfield, as was the black-haired fellow; it was the first time over there for the women but your man had spent two years there already. It was a grand place to work, he assured them. There was lashings of work available and as many Connemara people around as you’d ever wish for.

There were times when you didn’t need a word of English in the pubs or in the dance halls – that’s how many Connemara people were living there now. You’d almost think you were back home, a lot of the time. It was an amazing country, really; there was as much work there as anyone wanted. One of the sisters was going for hospital work over there and the other was hopeful of getting a job on the buses. A girl from their village was already working as a clippy in Bradford and there was no telling how much money she was making – if you were to believe what people said….

Oh! There was big money to be made over there, alright… no word of a lie. That said, they worked ferociously long hours for it, the Mayo women and the Donegal women, especially. They were mad for overtime, the young man confirmed. Some of them never wanted a day off and just worked non-stop from Monday to Sunday; some sort of madness for work and money came over them the minute they crossed the water! Wasn’t it a great thing too – to have the freedom to work as much as you wanted? – the younger of the sisters said. It beat working as a domestic for half-nothing back in Salthill, Galway, any day of the week! People were getting chances now that they’d never got before and they had to grab them with both hands.

The talk of England went on for a long time and only gradually petered out, as darkness fell. It was as if the loneliness of their leaving had usurped the moment again. Even the big red-haired fellow went 14silent and stared out of the window. They were passing through the countryside around Westmeath. The atmosphere was slightly awkward now that everyone had gone silent. It was as if all the energy and life had drained out of them as night drew in. What kind of a curse was on the Irish that they were driven out of their own land, generation after generation? Niall cursed to himself. Not only that, but they’d been an independent country a full thirty years since!

On an impulse, Niall blurted it out. Did it bother her that so many of the Irish were leaving home like this? The russet-haired girl stared at him momentarily as if confused by his question. It was a real failure, certainly, but there didn’t seem to be any way out of it, she said.

And maybe there wasn’t. either…. And yet this resigned and helpless attitude irritated Niall and made him angry at his own country and people. It couldn’t be that God had pre-ordained matters in this way – that the Irish were always exiles – so that in the end, there was no-one whatsoever left living in Ireland. Now and then the train stopped at some small country station or other and voices reached them from the other carriages: a sudden screech of laughter or notes of music. Youngsters passed up and down the passageway outside their carriage, giddy young lads horsing around and burning up some of their pent-up energy.

Most of the youngsters emigrating had only a little English; in truth, it may prove that they would be the last flowering of the Gaels and their culture, really. Christ, Niall said to himself. Why in God’s name was it that they always had to emigrate when it was all the anglicised bucks that were sitting pretty on the wealth of the country? It was enough to drive you mad and make you despair.

‘Yes, you’re probably right,’ he replied to the girl who was on her way to Norwold – wherever that was. ‘There’s nothing that can be done about it.’

‘We’re nearly landed now, I’d say,’ the girl said. She was right: the carriage was growing dark and filling with shadows. Scenes of the 15night outside were reflected through the windows, like ghosts of their own souls. A feeling of dejection came over Niall, for some reason: he was keen for this part of the journey to be over. He couldn’t wait to be chugging along southwards from Kingsbridge.

A yellow-red glow hung over Dublin city, the street-lights sparkled on the Liffey as they crossed over the bridge towards Westland Row. Only a few people disembarked from the train there because most people were heading for the boat at Dun Laoghaire, and it occurred to Niall that he was the odd one out here; the only one not taking the boat across the water with all these other people.

‘Well, I hope things work out well for you over there, sister’, he said, and shook hands with the girl, feeling awkwardly formal. Niall felt a slight lump in his throat as a dart of loneliness went through him, an emotion he couldn’t trace to its source.

Niall O’Connell had another pint in O’Mara’s on Aston Quay and then got the bus that brought him out to Kingsbridge; as always, when he was on Liffey-side, he felt estranged from the big city streets and the crowds of people rushing along them. There was something about all those ancient buildings and tall dark hallways that depressed him, even if he couldn’t explain why, exactly; there was something unsettling about these strange streets and faces. He wasn’t at home here. In his heart of heart, he knew that this city didn’t really belong to him at all. His mood brightened again on the train southwards, however.

There wasn’t any word of Irish to be heard now but at least he felt an affinity of sorts with the other passengers in the carriage; they offered some sense of permanency: they weren’t leaving their country forever. From now on, he’d have to make his own way in life as best he could, but who knew what the future held; maybe he could do his own small bit for the country? Even to keep living in Ireland now was an act of patriotism; it was some form of what the politicians referred to as ‘practical patriotism’, and it was now up to him and his like to offer 16their lives for Ireland, just as previous generations had once died on her behalf. Niall was glancing at a copy of the Evening Mail that he’d bought from a poor-looking ragamuffin boy on O’Connell Bridge when a small elderly man began to make conversation with him, and they continued chatting until they reached Carlow where the old man got off the train. It was nice to have had the company. A former hero of the Irish War of Independence, the man thought that Ireland was a great country now; life was improving every day, he maintained, they were building fine new houses instead of the miserable cabins that had been there when England ruled the roost; they had their own energy supply and their own industries, they had their own army and their own government (in most of the country anyway – and they’d have it all back sometime in the future); they were respected in the United Nations and in other foreign countries now as well. Normally, Niall wouldn’t have bothered arguing with an elderly man but his smugness annoyed him, especially when Niall thought of all those fine Connemara people who’d be ploughing the waves across the Irish Sea tonight – and all because they didn’t have any work in their own country. What about all the emigration, he asked the old man crankily? What about the way the countryside was left decimated as the nation haemorrhaged its own people? Was it a sign of progress that the pride of Ireland was leaving in droves every day? Niall asked. The man, who was sitting beneath an old smudged picture of Keimaneigh, gave a small understanding laugh but his eyes lit up all the same; there was nothing he seemed to like better than having a bit of debate with this assertive young lad.

No doubt about it, there was emigration and a lack of work but, then, it wouldn’t always stay this way. After all, Rome wasn’t built in a day. You had to walk before you could run, and we had to give the country a chance yet. We’d been under the British yoke for years and years; we’d been beaten down and destroyed by them – or nearly destroyed, anyway, he said. Those devils had never managed to quite 17get the better of us despite their best efforts. Look at how the embers of freedom had smouldered away within us for centuries and we’d had the courage to fight back again and achieve independence, even after long years of oppression. There was nothing that he wouldn’t do to protect the freedom that we’d now achieved, the old man said. Nothing at all. No young hooligan of a British soldier would ever set foot on our land again, no way; he’d have to deal with him first! And it wasn’t the end of the world either that there wasn’t a man or woman in the country yet over the age of thirty who hadn’t been born beneath the English flag. Hadn’t he seen big changes, even in the short years since he’d been out with his gun himself, and nearly all of them for the better, too? Ardnacrusha, Bord na Móna, the beet factories – there hadn’t been sight nor sign of any of those when the English were in charge; and there wouldn’t be neither had the British still been here. Look at the way we’d remained neutral during the war! It was thanks to the Long Fellow, Dev, God bless him; he was the only person that could have brought us safely through that crisis, and in spite of Churchill and Hitler himself. The nation would be forever in Dev’s debt for this. We needed to be patient, therefore, the elderly man said, in summary; if we were, we’d see the country thriving again one day, all the way from Rathlin Island down to the Blaskets. Niall hadn’t it in him to contradict the man; he and his like weren’t to blame for the bad state Ireland found herself in now either – whoever else was responsible for it. His generation had done their best when they’d had the chance – that was as much as you could ask for.

Yes, Niall had said to the old hero. There’s a lot of truth in what you’re saying, for sure. First there was Carlow, Bagenalstown, and then onto Gowran. As they came closer to his destination, Niall felt a little anxious. It must have been his longing for home again. He wanted to get going on his life as he’d planned it out. And he wanted to meet Peg Dinneen again if she was still around. A whole raft of different feelings coursed through him at once, leaving him with a vague 18uncertainty. He took a heavy drag on his cigarette as if trying to savour the full significance of the moment: this, his return home. One part of life had just ended; another was about to begin, and he needed to soak up every minute of it, draw it out for another while and prepare himself for whatever the future might hold; it beckoned to him as a veiled woman might signal in secret.

They were already crossing the bridge at Malogue, and the street lights at the edge of town winked one by one. The train slowed and came to a stop. Everything was as Niall remembered it the first day ever; for a moment, he imagined that he’d gone back into the past or that time had stood still. He stood for a moment at the door of the station and looked down the street. What he saw only added to his illusion of it being an unchangeable place. They were still there, the same group of men, all with their backs to the wall outside Ritzy Gorman’s pub, silhouetted in a yellow streak of light. They all had the same lazy look; it seemed as though they’d never moved. Across the road from them, the lights of Saint John’s Church illuminated the people coming and going in dribs and drabs from Confession, the elderly men lighting their pipes at the gate of the church, groups of women chatting together in groups. Down on High Street, the weak chimes of the City Clock announced time as the smell of turf fires wafted across the cool air of night. Niall took it all in again, and a warm familiar feeling came over him. The unease he’d felt earlier dissipated like a thin layer of fog beneath the sun’s rays. He swung his small travel case and walked quickly down towards the town, whistling quietly to himself with contentment. He was home again.

Chapter 2

Norwold hospital was situated on the edge of the town. It had a nice area of land around it with a border of evergreen trees. Gravel walkways led to the hospital grounds from the main road, and into a large three-storey brick building covered in thick ivy. The place was very different from the way that Nano had imagined it. She’d pictured it as a grim place, empty, bare, cut off from the normal flow of the world and the eternal stream of traffic outside. It wasn’t as she’d imagined it at all when she’d sent in her letter applying for the job as nurse assistant…. Unqualified nurse assistants urgently required. Good pay and board. RC Church nearby. Address your correspondence to The Matron, Norwold Hospital, Norwold, England, the advertisement in the Connacht Tribune went. Nano had, for a few weeks, mulled over whether to apply for the job before putting pen to paper. And, even then, she’d been unsure. She’d been in two minds until the very last minute, or at least that’s what she’d told herself. Thinking back on it, however, Nano knew that she’d made up her mind the instant she read the advertisement: she’d already decided in her heart. She didn’t have much of a choice, really, because if she’d stayed at home, she’d be in the way of her brother, and it was well past time for him to get married. Her only other choice was to leave, and hope that Máirtín would get a move on once she’d gone. But what were the chances of that, really? The truth was that Máirtín had no control over his situation – no more than she did. He was in a bind as much as any man had ever been.

It had been on the Sunday night after the ceilidh in Spiddal when 21they were cycling home together that she broached the question of the hospital job with Máirtín for the first time. She’d already put the letter in the post by then and this was probably the reason that she’d felt a bit out of sorts earlier that evening. She’d been in a strange and melancholy mood all evening, a feeling that she couldn’t really pinpoint other it being down to her having already made her decision. It was as if she was seeing the old place and everyone in it properly for the first time ever – as though through someone else’s eyes. She noticed things afresh, details that she’d never noticed properly before. It was as if change had crept up on the place, almost without her noticing. All those young and pretty fillies were turning into beautiful-looking young women before her very eyes, all the long-limbed youths transforming themselves into handsome men. Looking back on it, this was something that had frightened her: it was strange the way all the crowd she’d grown up with were getting old already, the fresh beauty of youth abandoning them like leaves on autumn trees. Combined with this mixture of sadness and regret that drifted over her then was the feeling that she should make her peace with certain people that she hadn’t spoken to for a long time. She started chatting to Julie Phádraig Pheicse, a lump of a girl whom she hadn’t had much time for since they’d had a row one day in the sock factory, a factory that was closed down now. She did the Stack of Barley with some tough young lad from a village back further west, a fellow who never shut up all the while they were dancing and kept asking could could he leave her home. It was as if she’d already left this place in her mind, there was no point in having a row with anyone because she was no longer part of this community. This feeling had stayed with her all night until the ceilidh came to an end and they played ‘Amhrán na bhFiann’ (The Soldier’s Song).

It was when they’d negotiated the hill and were freewheeling down the other side that Nano raised the question of the hospital with Máirtín. The magical white gleam of the autumn sun illuminated the 22small rocky fields, it shone golden and smooth on the surface of the sea as the wheels of their bicycles whispered secretly on the tar road. This moment was beautiful; so too was the night, and it only bolstered the intimation that Nano had felt earlier; it was a reminder to them of life’s fleeting nature. By this stage of their lives, they should not have been returning from a ceilidh; they should have been busy with their own lives, raising their own family in their own house.

‘Guess what I did the other day, Máirtín?’ she asked him half-quietly.

‘What? I don’t know, I swear!’ A surge of anger enveloped Nano. How could Máirtín be so oblivious to the conflict that was going on inside her? She felt an urge to hurt him back, to pierce his complacency.

‘I wrote to England, to Norwold, wherever that is, looking for a job in a hospital there. It was in the Connacht last week.’

Máirtín didn’t reply: he was a man of few words at the best of times. Normally his silence wouldn’t have bothered Nano in the slightest. Máirtín Bhid Antaine had never been much of a talker and anything he said was carefully weighed-up beforehand. He had a quiet confidence and he was a kind-hearted man, and if it wasn’t for the fact that there were family issues preventing him, they’d have been married years ago.

‘Looking for a job, is it?’ he said, but Nano couldn’t read anything into his deadpan tone. For a while, there was no sound in the world except for the whisper of the bicycle tyres along the gravel road. A little later, as they stood outside the gate of her house, Máirtín asked Nano to wait and see how things turned out.

‘You’d be better off waiting a while so that we can see how things go, Nano,’ he said, but despite herself, she reacted badly.

‘See how things go, Máirtín? By God, but we’re long enough waiting to see how things go – and we’re not seeing anything!’ She was tempted to add ‘we’re long enough looking at one another’, but 23that would have been going too far. That would have been unfair to him, because the truth was that Máirtín wasn’t to blame for their situation any more than she was herself.

Nano Mháire Choilm was twenty-six years of age and Máirtín Ó Spealáin was thirty. It was time for the pair to get their act together, but how? It was the old mother-in-law situation. Máire Bhid Antaine would never have welcomed a new bride onto her turf, no matter how fine and easy-going a person she might be. And Nano had no interest in forcing herself on her either. There were two women in that house already, in any case, even if Máire was counting the days until her sister Anna in Boston sent for her. And it wasn’t as if Máire was standing in the way of Nano coming into the family either; she’d said as much to Nano often enough; she, more than anyone, would’ve loved to see Máirtín married. But Mammy was the problem, said Máire, adopting the English term and imbuing the word with a certain grandness, as was a habit of hers. Mammy was the boss, when it came down to it. Nano forgave Máire this little hint of grandeur because Máire was still young. And she’d plenty of good points about her too, to give her due; and anyway, her opinion didn’t carry any weight. It wasn’t true to say that Máirtín was completely under his mother’s thumb either, even if this was the main reason that he wasn’t married yet. It wasn’t as simple as this, unfortunately. Bhid Antaine held an advantage over her son that was difficult to counter; she had a problem with her heart that meant Máirtín couldn’t put too much stress on her. Nano knew full-well that Máirtín would go to England or anywhere else with her the next morning rather than waste any more of her life on her back here – if he’d only been allowed to. But he wasn’t! He was completely trapped here and unable to move backwards or forwards, really. Because his mother’s health was so bad, Máirtín couldn’t take the chance of pushing her beyond her limits. His mother was a woman who hadn’t had it easy, as Máirtín had explained to Nano: he couldn’t just leave her there at home and entirely reliant on the neighbours, 24given that that she was so fragile and coming to the end of her days. But then, of course, he wouldn’t have had to leave her at all had his mother just given in a little bit, had an ounce of understanding or had been less stubborn. The problem was that his mother didn’t have any ‘give’ in her. And any time that Máirtín raised with her the question of marriage and bringing a woman into the house, Bhid Antaine’s response to Máirtín was always the same – it wasn’t the right time yet and she wouldn’t be in their way much longer. In reality, the old woman was just using her heart problems as an excuse, Nano knew – and this was not to her credit! In truth, Máirtín’s mother could probably still live on for years and if she had her way, there was no chance that they’d be married this Advent nor the following Advent, nor any other Advent for the next ten years. Meanwhile, they’d be getting older all the time, Máirtín and herself, the same as all the other couples who let the years pass them by until, by the time they finally got to the altar, they were nothing but a laughing stock. Wasn’t it often said of youngsters who were itching to get married in that part of the country that they should go and ‘get a room in Bohermore’ – the new housing estate in Galway city – seeing as they’d be a long time waiting to get the home-place. And these younger couples were the more enthusiastic and go-ahead ones – or the ones lacking sense, whichever way you looked at it. Nano Keane would’ve preferred to move away from the countryside and into a housing-estate in the town, bad as it was, rather than this never-ending dance of courtship that herself and Máirtín had going on. But look it! Even that solution had been denied them!

‘If I could get our Peadar to come home,’ Máirtín always told Nano, ‘I wouldn’t spend another day in this place.’ His repeating this mantra was by now like rubbing salt into the wound, however. It made no sense.