Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

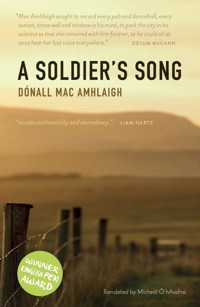

'Mac Amhlaigh sought to record every pub and dancehall, every sunset, stone wall and rainbow in his mind, to pack the city in his suitcase so that she remained with him forever, so he could all at once hear her lost voice everywhere.' – Colum McCann 'Mícheál Ó hAodha has done the literary world a huge service by translating Dónall Mac Amhlaigh's work into English.' – Gillian Mawson 'a work that exudes authenticity and immediacy.' – Liam Harte A Soldier's Song is a classic account of Irish army life by a working-class writer whose work and contribution to literary culture is only now being fully appreciated. It has the privacy and immediacy of a diary but holds the interest like a novel. It follows the adventures, trials and tribulations of Nuibin Amhlaigh who keeps getting into trouble in his good soldier's progress through army life. A lost treasure of Irish writing translated for the first time into English.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 482

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

About the Author

With Support from

Praise for A Soldier's Song

Title Page

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Parthian Translations 1

Parthian Translations 2

Parthian Translations 3

Supporters

Copyright

Dónall Mac Amhlaigh (1926-1989) was one of the most important Irish-language writers of the 20th century. A native of County Galway, he is best known for his novels and short stories concerning the lives of the more than half-a-million Irish people who left Ireland for post-war Britain.

A prolific journalist and a committed socialist in the Christian Socialist tradition, Mac Amhlaigh, whose diaries and notebooks are held in the National Library of Ireland, was a member of the Connolly Association in Northampton and contributed regularly to newspapers such as the Irish Press and a range of journals on both sides of the water throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In his writings, Mac Amhlaigh often provided the perspectives of the Irish in Britain on issues such as class, economy, emigrant life in England, the conflict in Northern Ireland and civil rights-related issues.

Mícheál Ó hAodha is an Irish-language poet from Galway in the west of Ireland. He has written poetry, short stories, journalism and academic books on Irish social history, particularly relating to the Irish working-class experience, and the Irish who emigrated to Britain. He is one of the very few poets since Ó Ríordáin to explore the metaphysical in the Irish language, his work encompassing themes of loss, longing, memory, love and forgetting in collections such as Leabhar na nAistear (The Book of Journeys) and Leabhar na nAistear II.

With Support from

Praise for A Soldier’s Song

Dónall Mac Amhlaigh’s contribution to Irish literature has been long neglected. He is the greatest chronicler of the Irish navvy slaving on English building sites. It is quite amazing that of all our emigrant millions the best that has been writ and said of their lives and times has been written in Irish. But before he joined the great exodus to the digging holes of England, Mac Amhlaigh was an Irish soldier. Not being a military people, the Irish people have little respect for their army. The author’s account, ostensibly autobiographical, but undoubtedly with some fictional flourishes as would befit a novelist, makes for a great read. This soldier’s story does not include great wars, but just the fun and competition and camaraderie and happenstances of young men who end up in uniform. It is funny and sad and wistful, and a portrait of a time and experience which has never been captured quite like this. Mícheál Ó hAodha’s translation brings us right into his world, giving the original Irish a new life with style and with verve.

Alan Titley, translator: The Dirty Dust: Cré na Cille

Mícheál Ó hAodha has done the literary world a huge service by translating Dónall Mac Amhlaigh into English. It is one of the few novels (in either Irish or English) which explores the ‘silent generation’ of Irish who emigrated, primarily to Britain, to find employment in the post war years. Originally written in a minority language which is fading fast, it explores Ireland’s urban environment as opposed to a rural one. As such, it is a unique and important part of Ireland’s social history.

Gillian Mawson, author of Britain’s Wartime Evacuees – Voices from the Past

Dónall Mac Amhlaigh’s A Soldier’s Song is a work that exudes authenticity and immediacy. It bears the stamp of the author’s distinctive voice and companionable persona, the idiosyncrasies of which translator Mícheál Ó hAodha has deftly captured in this fine translation that gives fresh, twenty-first-century life to a lost literary treasure.

Liam Harte, Professor of Irish Literature, University of Manchester. Author of Reading theContemporary Irish Novel 1987-2007 (2014) and The Literature of the Irish in Britain: Autobiography and Memoir, 1725-2001 (2009).

Dónall Mac Amhlaigh’s A Soldier’s Song demonstrates why Irish is one of the oldest written vernaculars in the world. In a language vibrant to its very core, Mac Amhlaigh gives a picture of a country and a people that have been central to the European imagination for centuries. He captures precisely the psychoses, the sadnesses, the joys and the prejudices of a people forced into the music of survival. This novel is as much about the change from rural to urban in Irish life as it is about a young man’s hopes and dreams in a post-war Europe just coming-of-age. Written just before he left Ireland for a new life in Britain, Mac Amhlaigh’s novel is a paean to the city of his birth – Galway – its people, pubs and streets. Like Joyce, Mac Amhlaigh sought to record every pub and dancehall, every sunset, stone wall and rainbow in his mind, to pack the city in his suitcase so that she remained with him forever, so he could all at once hear her lost voice everywhere.

Colum McCann, U.S. National Book Award Winner

A Soldier’s Song

Saol Saighdiúra

Dónall Mac Amhlaigh

Translated by

Mícheál Ó hAodha

Chapter 1

It is my last day working for the O’Neill’s in Salthill. It’s Monday, the 3rd of November, 1947. I’ve spent four months working as a waiter in the hotel here, but the tourist season is over now and I can’t expect them to keep paying me for the winter when there’s nothing to do around the place anymore. Myself and Maitias Ó Conghaile from Doire Fhatharta1 are enlisting in the army tomorrow – if we’re accepted that is; and then it’s goodbye to Galway for the next six months. We’ll be training up on the Curragh, in Kildare.

But then when I went down to Joe’s house, they thought that I’d lost the plot. I told them what I was doing and Joe says: ‘What the hell would you want to join the army for?’ grabbing the tongs and giving the fire a poke. His wife Meaig arrived in just then too carrying two buckets of water. She was just back from the well.

‘What’s this about the army? Who’s joining the army? It’s not that lazy little good-for-nothing of ours Peadar is it? He’s not going on about joining the army again, is he! As if it’d do him any good! All the young crowd today is the same. All they care about is soldiering – either that or leaving for England.’

‘Arah, keep quiet you, you divvy, and mind your own business, will you?’ says Joe gruffly, the same as always. ‘Peadar hasn’t a notion of joining the army. It’s Danny here who’s thinking of joining up.’

‘And that’s his choice too,’ says Meaig, once she realised that it wasn’t her own son that was joining. ‘Let him be let you. Shur, can’t the young lad do whatever he likes? There’s nothing wrong with the army at all, you know – shur wasn’t his own father in the army? I don’t know why people are always telling others what to do anyway – instead of just listening to them for a change. There’s no fear that they’d mind their own business anyway!’

Meaig was thick that she’d to go to the well when her husband and son were in warming their arses by the fire.

‘Eh? What’s this I hear about our Danny joining the army?’ says Daideo2 shifting beneath his quilt.

‘Hey – this lad here’s hoping to enlist in the soldiers the same as thousands before him. I don’t see what you’re all worked up about. God knows, you lot are worse than a pack of children, the lot of ye,’ says my cousin Peadar, chipping in.

‘Still, I think you’d be mad to tie yourself down like that Danny,’ says Joe.

‘The army? – There’s never any of God’s luck where there’s soldiers,’ says Daideo, gobbing into the fire. The ‘Tans’ came within a whisker of shooting him dead during the Troubles, the same man he’s had it in for soldiers since then – not that I can blame him in fairness. Joe shook his head ruefully: ‘I never passed that (i.e. Renmore Barracks) beyond that a chill didn’t go up my spine at the sight of the high walls and giant iron gates. It’d remind you of a prison more than anything else.’

Meaig opened her mouth to say something else, but Peadar got in before her. ‘Will you make us a cup of tea there Mam? Suit you better than spouting off about stuff that you know feck-all about!’

I stayed there with them until I’d my tea drank and left them to it. I could tell by him that Joe’d try and knock some work out of me if I hung around much longer. Maybe that’s the reason he’s not keen on me enlisting either. Many’s the day’s work that he’s got out of me for free. I don’t care anymore, though. I’ll do my own thing from now on, and I’ll be back here in spring again wearing my green soldier’s uniform with the help of God.

I felt a kind of sad leaving Joe’s house, especially when I looked across at the Burren Hills on the far side of the bay and the Aran Islands at the edge of the horizon – like something that’d emerged from the sea. Rahoon and Letteragh to the north of me and Barna Woods to the west, the entire landscape shrouded in that strange and beautiful silence that permeates autumn in this part of the world. I thought back to those days long ago when we arrived home from school, autumn afternoons just like this one, when we arrived in starved with the hunger. And no matter how hungry we were, we’d pray that our mother hadn’t made stew that day. Anything but stew!

I walked over to Salthill and called into the hotel to see whether they’d anything for me to do. They’d no jobs for me though and told me to take the rest of the day off instead. I’ll sleep in the hotel tonight, but from tomorrow on, I’ll be up in the Curragh of Kildare probably. I’ll be sorry to say goodbye to Seán and his wife after this long with them. They were always very nice and kind to me even if we got on each other’s nerves the odd time when things were hectic at the height of the tourist season; it was always worth it. They always treated me as just another member of their family and not like a boy who was working for them.

I went down to Micilín’s house (Maitias’ brother) in Buttermilk Lane and I stayed chatting with Micilín and his wife until Maitias arrived in from Tirellan where he’s working for a local farmer. God, but we’ve had some great nights in that house there, listening to the gramophone and dancing the ‘Stack of Barley’ and the ‘Half-set’. The Carraroe and the Eanach Mheáin3 people are the ones who go there most and you’d hear many fine songs sung in the real ‘sean-nós’ style in that place. Mugs of tea and big hunks of currant cake passed around the room then by Micilín’s wife and a nice long chat once the dancing was over and she told us all to go home for ourselves. Maitias and I went for a wander around Galway town then and we met the girls. The two girls we met had just finished work for the day – Juleen and Margaret – and they work over in the hospital laundry. Maitias and I started going out with them – him with Joyce and me with Margaret. We were going out with these girls ever since Race Week.4 I was only just back in Galway from Kilkenny when I met Margaret and I’d lost most of my Irish by then because of the length of time I’d spent away from Galway. Once I started going out with Margaret, my Irish came back to me again quickly as she has no English worth talking about. She’s a fine-looking girl with beautiful long black hair and she loves slagging and joking and having the crack. Mind you, she was a bit sad in herself tonight. She said she’d miss me when I’m gone. She told me she’ll be waiting eagerly for me to return to Galway again. I feel the same way about her as well, of course.

Just after we were saying goodbye to the girls at the hospital gates they called us back again and told us to call to them again tomorrow afternoon again before we leave – that they’ve a message for us to do downtown for them. Then they ran quickly back inside into the hospital.

Maitias and I stayed chatting down near the bridge until fairly-late and to make matters worse again, Seán Ó Néill was still awake when I got back to barracks and insisted that we drink a few bottles of beer together to mark the occasion of our departure from here. Well – that’s me finished with the work in O’Neill’s pub now although they said that they’d welcome me back with open arms anytime I wanted a job there again. A hundred farewells to my small box-room at the top of their house and the stunning view of Galway Bay all laid out before you on a moonlit night. If I get on as well in the future as I did when I was working in Salthill, I’ll have no complaints. It’s time for me to stop writing this now and go to sleep.

1 Doire Fhatharta, Carraroe, County Galway.

2 Daideo – ‘Grandad’

3Eanach Mheáin – Annaghvaan

4Galway Races – The Galway Races is an Irish horse-racing festival that begins on the last Monday of July each year. It is held at Ballybrit Racecourse in Galway, Ireland over seven days; it is the longest of all the race meets that occur in Ireland.

Chapter 2

Maitias met me at the corner of Eyre Square the next day and we went over to the hospital to see the girls one last time. We got through the main gate without too many questions and into the laundry where the girls work. Oh little brother, but you couldn’t see your hand in front of you with the steam that was in the room and you couldn’t hear yourself think with the racket and spinning of the huge washing machines there. Once the steam cleared somewhat, we saw the giant vat of soap and water and the Connemara girls up to their elbows in water. We called over to the girls, but they just giggled and waved some old pairs of drawers in our direction. Margaret and Juleen emerged from the steam in the end, laughing and giggling at the antics of the other girls. They couldn’t talk to us for long though and we said goodbye quickly again. Believe it or not, they gave us a half-sovereign each as a parting gift! God knows, this was a very kind gesture on their part, especially when they aren’t very well off themselves at all; they only got paid one pound, one crown per month in addition to their food. I was lonelier leaving Margaret than I thought I’d be, but we’re going to write to one another every week until I’m back home again.

Maitias and I went over to Renmore again, but at the barracks gate, they told us that there’d be no doctors available for the next few days. We were better off heading down to Athlone ourselves we said, because there’d be a doctor there who could do the medical immediately. We got the three o’clock train, even if we were a bit quiet passing over the bridge at Loch an tSáile and on past Baile Locháin. When we enquired at the gate of the barracks in Athlone, the army policeman gruffly told us go away first, for some reason. It’s not as if we looked rough or untidy at all or that we were flat broke or whatever either. He let us in eventually and we followed the barracks assistant to the storeroom where we were each given a mattress, two pillows, and sheets and blankets. We were led into a long wooden cabin and told to pick where we wanted to sleep until the exam the following morning. Maitias showed me how to dress a bed the way that a soldier’s supposed to do it – (he spent a while in the Preparatory Corps so he knows these things) and then we went over to the canteen for a cup of tea. There were a good few soldiers there already, some of them drinking tea or playing billiards or just listening to the radio. I couldn’t but envy these lads who’ve their training done already, not that I’d want to be stationed in this barracks here, however. We’re lucky that we’re Irish speakers, otherwise, we wouldn’t be sent back down to Renmore again at all, once our training’s done.

We bought tea and scones and sat at the table nearest the fire, and one of the soldiers wasn’t long coming over to us, a big block of a lad with fair hair. He asked us where we were from and whether we’d been accepted for training yet and once we told him that we were joining the Irish-speaking An Chéad Chath, what do you know but didn’t he switch to Irish! He’d good Irish too, by my soul, other than that he had a strange dialect. He was from Turbot Island out from Clifden and he’d a year done in the Army already. I got the feeling that Maitias wasn’t over the moon that this fellow had joined us. I offered him a drop of tea and a few scones, and he kicked me in the ankle under the table unknown to the other fellow. This Clifden lad was broke; he didn’t even have a cigarette on him, but tomorrow’s pay-day – and so before he said goodbye again, he made sure to bum a few cigarettes off Maitias.

We headed out the town then and spent an hour or so hanging around. To be honest, the place didn’t seem like much to us. It wasn’t a very lively spot – not compared to Galway anyway. Back in Galway, you’d be meeting girls and boys from Connemara every few minutes as you walked down the street, but this place was different. It was strange to our eyes.

‘You’d be a long time waiting for someone to speak a bit of Irish to you here,’ Maitias says, ‘you might as well be out in Hong Kong for all the chances of that happening.’

I slept like a baby the first night even though the bed was as hard as a rock. In the morning, we ate breakfast in the canteen with the soldiers and then put the bed-frames and the bedclothes back to the store. We were brought down for our exams then – tests in numeracy, writing and geography – after which we’d to go to the doctor’s for the medical. Before this exam took place at all however, the Recruiting Officer asked us whether we’d still be happy to join the army even if one of our friends was refused admission on medical grounds. Maitias and I looked at one another momentarily before responding as neither of us was quite sure what to say to this. We told the Officer that it’d benefit neither of us to turn down our chance in the army just because another lad was rejected and so they went ahead with the medical. We needn’t have worried though because we were both out again two minutes later. We’d got through. Next, we were instructed to take the oath. We did that and then we were given our travel passes for the journey down to Kildare. One minute we were two ordinary civilians and the next we were fully-fledged members of the Irish Army! My heart swelled with pride and joy at my new status and I told Maitias as much too as we left the barracks again, seeing as I knew he felt the same way about it. He told me to cop on to myself though and that there’d be time enough for me to be talking pride and all the rest of it once I’d actually completed my army training and had my proper qualifications.

The train we boarded had just arrived in from Galway and by chance, we ran into a group of boxers from An Chéad Chath. They were on their way up to the Curragh for a boxing tournament. The lads all looked manly and neat in their fine-polished uniforms and shoes and their bright-shining brass – and the insignia of An Chéad Chath prominent on their uniforms. I can’t wait for my training to be done here so that I’ll be as well as qualified and as well turned-out a soldier as any of them. They all spoke Irish to a man and you’d go a long way before you’d find a finer-looking body of men anywhere, I’d say. On reaching Kildare, there was an army lorry waiting for us and Maitias and I were given our instructions straight away by an army sergeant there. We climbed into the back of the lorry and travelled out along the narrow road that splits the green sward of the Curragh Plain.

***

Our work today in McDonagh barracks – or the ‘General Training Depot’, as they call it – was the same as yesterday. After we’d collected our mattress and sleeping gear from the store we were brought over to a big barracks-room full of new recruits, all of whom were getting their beds ready for the night. There was a big turf fire at the top of the room, but the beds nearest the fire were all taken already by the lads who were ahead of us and so we’d to be happy with two beds far away from the heat. It doesn’t matter though, because we’ll only be in this room for a few days by all accounts. Once other Irish-speaking recruits arrive here, we’ll get our own room at the far end of the barracks. We started to unfold the blankets, but the Sergeant stopped us. ‘Don’t bother with that yet,’ he said, ‘come with me so that you can pick out your kit.’ We followed him across the square to another building and then upstairs to where the Quartermaster was dividing out the kit amongst the recruits. It was getting late and he was about to finish up for the day and he didn’t look too happy at all to see us arriving in. We got in the queue and I smiled at him but he was right-grumpy.

‘What’s the smirking for Sonny – did you win the Sweep or something?’ – he says.

The store-man who was helping the Quartermaster divide out the kit didn’t look like he was too thrilled either; they just handed us whatever was at hand and it was obvious they couldn’t wait to get rid of us. He handed me a uniform that I thought looked alright until Maitias told me in Irish that it was all rucked up at the back and looked ridiculous on me. Maitias was right, of course. I found a uniform that fitted me fairly well in the end, and was handed the rest of my stuff. Oh little brother, you wouldn’t believe the amount of stuff that we get as our kit – shoes, shirts, socks, brushes, a wooden belt, a cap, a work uniform or fatigues, a button-stick and don’t ask me what else – everything thrown into a big canvas bag. A kit-bag they call it. They give you a big wooden box to store all this stuff in and it’s back from the Depot again.

I don’t know how in Jesus’s name I’ll keep track of all this gear, especially seeing as there are a good many of the Dublin gang in the room and they’ve a reputation for stealing that goes back years. Maitias says that we need to buy two padlocks for our stuff now or we won’t have a razor left between us after a few days.

We got tea at half past four. The canteen is directly opposite the room here and I can honestly say that I never tasted a tastier loaf of bread than the one we got this afternoon. One loaf between every five of us is what we get here, but it’s not nearly enough really. I know that I could eat a full loaf myself, no problem. We’ll have supper in a while, but this is just a mug of porridge, the others tell us. What harm? We’re not broke yet. Shur, we can always pay a visit to the canteen later.

We were woken with a start this morning by the loud blast of the bugle announcing Reveille. Next minute, the big sergeant arrives into the room, walking stick in hand. He raps his stick on the edge of the door and makes a racket loud enough to wake the dead, then he’s down through the room prodding and poking everyone with the stick and bellowing at the top of his voice:

‘Rise and shine, beds in line. Sluggards arise and greet the day! Any man not out on parade in five minutes gets put up on a 117. That, for your information gentlemen, is an Army Charge Sheet and something you’d rather not get acquainted with too soon. Shake a leg there, now, everyone up!’

I nearly fell out of bed, I was in such a rush to get up! Maitias told me to take it handy and not to be making an idiot of myself in front of all these strangers here. We’re given a minute or two to dress ourselves and make the beds. He was in no rush and yet he was still ready quicker than I was. I was still only half-dressed and Maitias was ready to go out on parade, his blankets carefully folded, one on top of the other. I wasn’t the worst of the lads there though, as by the time I’d given my hands and face a quick rinse and went downstairs, some of the other lads were still fiddling with their laces and stuff. Others raced out to the washroom, tucking their shirts into their trousers and all the rest of it.

Breakfast was nice and tasty (pity there wasn’t more of it!); we got an egg and a slice of bacon each, a big mug of sweet tea and a fifth of that fine loaf with the black crust on the end of it.

We still had a fair bit of time yet to prepare correctly for the Morning Parade and I polished the buttons on my uniform and shoes while Maitias went out to the washroom for a shave. A long slate edge jutting out from the wall serves as the washbasin here and there’s plenty of cold water any time you want it. You use cold water for shaving. It’s tough, but that’s the way it is.

We were ordered out on parade then, where a different sergeant again spent a while trying to get us some way organised before the Company Lieutenant appeared. He was a very young man to be at that rank, I thought, but he walked up and down and inspected us all closely, then gave us a short lecture. You’re in the Army now, he said, and we can make a good life for ourselves here if we want to. It’s up to ourselves. If we do everything that we’re told, no one’ll find fault with us, but if we try and act all hard and that, we won’t be long finding out that the Army can be ten times harder than us. And we won’t be long finding out who’s really in charge either, he told us. To have a fine, manly life for ourselves while we’re wearing the uniform, we’ve to make sure we complete our duties carefully. We need to understand that the sergeants and other army personnel here, irrespective of rank, are our friends, he said. We shouldn’t ever hesitate to ask them for help at any stage, especially if we’re anxious or worried about anything. One lad standing behind me mumbled sarcastically under his breath all the while the Lieutenant was talking. This fellow was in the Army before by all accounts, but he left once he’d his initial training over with. I don’t know what in the name of God brought him back here again because all he’s done since yesterday is give out everything about the Army non-stop. This fellow has the ability to talk without moving his lips, like a ventriloquist nearly, and it’s hard to tell where the muttering is coming from sometimes. Maitias says that this trick of being able to talk under your breath like this is a pure sign that he’s spent time in the glasshouse or Military Prison, but I don’t know if that’s right or not. When we scattered after parade, Sergeant Sullivan came in with orders for me and Maitias. Sullivan’s a wiry, tough-looking fellow with ginger hair, and he has the bluest and most piercing eyes I’ve ever seen. It’s like he’s looking right through you. I wouldn’t like to draw this fellow onto me, I can tell you.

We’ll have our own room shortly, he told us, as soon as other Irish speakers arrive here. We’re to have our training in Irish and that’s what we’d prefer too seeing as I can’t see us really gelling with the crowd that we’re in with right now – because of different languages. For example, Maitias and I were chatting last night after ‘Lights Out’ when we heard someone sniggering in the dark. The sniggering went around the room until everyone was laughing and mocking us – for speaking in Irish, of course!

Maitias’ very impulsive and he jumped out into the middle of the floor and challenged them. This quietened them for a while even if there were still some smart comments from the ones who were taking the piss out of us after this too. I told them that it was a bit rich for them to be making fun of us, considering that we had two languages and they had only one – ‘and that one only half-right at that.’ Oho son, but that really got their goat! Next minute a big, tall fellow jumps up out of his bed in anger to tell me that I was ‘out of order’ saying the likes of this:

‘That’s a very serious thing to say about anyone, making out we’re illiterate or something. I’m not forgetting that remark, mind, and I’ll make a complaint to the C.O. tomorrow.’

I wouldn’t mind but this fellow could tear me apart if he wanted to; he’s bloody huge – never mind running off to the Company Captain with his stories.

We spent the day at various odd jobs. First, we’d to leave our civvies in the kit-bags in the store, take a bath, get a haircut and then sign various papers. We were marched up to the Medical booth this afternoon for blood tests and who was there already when we got in but the lads we’d been exchanging jibes with last night! You should have heard ventriloquist-man giving out as we moved up the line to give blood. The way he went on you’d have sworn the medical orderly was ready to stab us with a pick instead of getting the small pin-prick that we got in the end!

‘There’s no need for this at all,’ he said, chewing the top of his thumb where they’ll be taking the drop of blood from in a minute. ‘There’s no need for this at all. It’s all just stupidity and show. I was here before and they took my bloods already. Surely that’s down on paper somewhere. Wouldn’t you think they’d just go and check the records they have already, instead of making a pin-cushion out of me again?’ He kept whining like this until they took the blood sample from him and then went off holding his ‘injured’ thumb.

Group ‘O’ seems to be the most common blood group by all accounts, and tomorrow, I’ll be given a small medal with this blood group marked on it in addition to my I.D. number. ‘89383, Private, Mac Amhlaigh, Dónall’, is who I am now and my comrade Maitias is ‘89382, Private, Ó Conghaile, Maitias’. Seven-and-twenty a week is our pay until we’re fully trained. Then we do a one-star or two-star trial maybe, and if that goes alright our pay’s increased. You get a pay rise of seven shillings a week for every star you get.

This camp is a good and healthy place and it’s no wonder, seeing as at the lowest point out the countryside here, you’re as high up as the top of Nelson’s Pillar in Dublin – or that’s what they say anyway. There are thousands of sheep grazing the plains around here and strangely, they aren’t a bit shy of people. In the mornings they’re standing in the doorway as soon as you go outside and they sniff around the swill-barrels outside the canteen on a regular basis. There are seven barracks altogether in this Camp, each of which is named after the leaders of the Easter Rising. There are two picturehouses here too as well as one ‘dry’ canteen; we’ve plenty of opportunities to spend some of our wages here so I plan on sending a half-sovereign home every week with the help of God.

Today we were moved downstairs to the bottom room and Maitias and I grabbed the two beds closest to the fire the minute we went in, needless to say. Sergeant Red said that he expected us to keep this room as clean as snow at all times; for some reason, I felt that he was directing this instruction at me mainly. Another lad joined us today, Ó Murchú (Murphy) from Limerick, and he has excellent Irish, even if he didn’t go past National School for his education. He’s a small, bony but muscular fellow who always has an anxious look about him – as if he’s expecting someone to play a trick on him or to cheat him out of something any minute. He and his father worked for a local farmer down in Limerick until recently and they were paid 70 pounds a year in total – this was their pay, including the use of a house, a garden, milk and the like. Isn’t this a strange arrangement all the same? To give Connemara it’s due, at least every man working there has his own smallholding and isn’t at the mercy of some local big farmer or landlord. As the song goes:

Seal ag tarraingt fheamainne cur fhataí is ag baint fhéir,

Is ní raibh fear ar bith dá bhoichte nach raibh áit aige dhó féin,

(At times cutting seaweed, sowing potatoes or saving hay, / And there was no man so poor that he didn’t have his own patch for himself.)

Would you believe it? I’m only in the army a few days and I already have a ‘charge’ against my name! We were on parade at nine o’clock this morning and the Lieutenant doing a careful inspection of us when he asked me whether I’d shaved that morning.

‘I didn’t sir,’ I replied.

‘Oh, do you see this Sergeant,’ he says turning to the ginger-haired Sergeant.

‘How come you didn’t shave?’ the Sergeant says gruffly.

‘Well, I don’t ever shave to be honest’, I says. ‘Because I haven’t started shaving yet.’

‘Oh, he doesn’t ever shave himself,’ repeats the Lieutenant, ‘have we any medicine for that one Sergeant, I wonder?’

‘Yes, we do sir. I’ll charge him after parade is over,’ says the Sergeant.

I was sent over to the Company Captain once we were finished and charged with being ‘unshaven on parade’. He let me off though when I explained that I didn’t know about this rule that you’d to start shaving yourself once you enlisted. The Sergeant gave me a right dirty look as I passed him on my way out of the Company Office.

Maitias tells me that I have to be on alert about them from now on as they’ll be watching me carefully to make sure I don’t make any other mistakes. Maitias knows a lot about the Army and he’s the great ‘survivor’ no matter what he does, so I’d be as well listening to him. We got a fine dinner today, a lovely piece of trout each with peas and potatoes. We were allowed just three potatoes each, but I felt full leaving the table all the same. I thought the food was fine, but the ventriloquist-fellow thought the fish was rotten. I’ve never come across the likes of him before. He complains about the slightest thing. Maitias calls him a ‘barrack-room lawyer’ and he’s warned me to steer clear of him as he’s trouble.

We spent the day learning how to march correctly in formation and were all fairly tired by the end. The Sergeant is witty and he’s full of quips and smart-alec stuff, but if you laugh at anything he says, he gives you a right bollocking. I was nearly fit to burst a few times and at one stage I couldn’t help myself and gave a snigger. He read the riot act with me. Maitias is very good on the marching and never needs correction on it.

This basement room we’re in is grand and comfortable and we’re at home here already, unlike the room above where the other crowd slagged us off for speaking Irish. Maitias reckons our gang will be as strong and close-knit as any soon – a lot more so than the crowd upstairs. Maitias ’s the type who likes a bit of rivalry methinks. He’s not gone on that shower upstairs and makes it very obvious.

Saturday, 8.11.1947

We’d a great big parade this morning – the Leader’s Parade – and it was one hell of a sight. Hundreds of soldiers in full battle-dress, spick-and-span, out on the large square, and the band playing marching tunes. All of us recruits were on parade and we looked fairly pathetic really compared to the crowd who’ve guns already. The Barrack Leader, a small wiry man with a swarthy face, went around inspecting us. He’d a pair of leather boots up to the knees and a riding crop under his arm. After the parade, our rooms were inspected and everyone had to stand next to their bed, their kit-box open next to them.

The Sergeant came around first to check that everything was in order. I thought my kit-box was fine, but when he came to me, he let a shout out of him: ‘The Chamber of Horrors!’ he says. ‘All y’need now is the Mummy!’ I had to empty everything out of the kit-box onto the floor straight away and then put it all back in again as quick as I could. The Company Captain inspected us a short while later again and he didn’t fault me on anything even if Sergeant Red stopped and had a good gander at me and my kit. We’d the rest of the day off and Maitias and I went for a walk around the camp. It’s a hellish lonely and isolated place really when you take it all in. Please God, I won’t have to stay here for good.

We’d to be back in time for tea and that Rattigan fellow, the perpetual whiner, sat at the same table as us. We’d eggs for tea, but he turned his nose up at the sight of them, like they were rotten or something. When the orderly dished out the food, he picked up one of the eggs and gave it a sniff.

‘The hen who laid this egg must be drawing the pension for years,’ he said.

‘What’s wrong?’ the barracks orderly asked.

‘O, nothing at all, Sarge, nothing at all,’ he says.

No sooner was the orderly gone but your man was in full-flow again though:

‘There y’are. You’re not even allowed open your mouth in this place. You might as well be in Russia.’

Maitias says that your man is a gammon hard-chaw and that he’s intent on causing trouble. Two other recruits joined our group this afternoon, a young lad from the Aran Islands, Martin Cooke and a lad from Tooreen in Mayo, by the name of Connery. I knew the pair of them to see already from Galway. The lad from Aran has hardly any English, but he’s a nice lad and bright, and I’ve no doubt that he’ll get on well here. The other lad’s very polite and I’d say he’s well-educated. Our number is gradually increasing. There’s a big group of new recruits from Dublin down the block from us here too. None of them are that big or strong, but they’re very cocky all the same. They christened me ‘Dev’1 from day one.

One of these lads asked me for a loan of my knife at tea-time. He told me he’d left his own knife back in the room, so I gave him a loan of mine. After tea I followed him out of the canteen and over to his room. Like a fool, I thought that he’d forgotten to give it back to me. When I asked him for it back, he looked at me as if like I was some sort of a nut.

‘Knife?’ What’re you on about?’ he says.

‘The knife I gave you there in the canteen just a few minutes ago.’

‘You never gave me any knife,’ he says. ‘Who’re you anyway? I never met you before in my life. Isn’t it true for me lads?’

‘True for you,’ chorused the other lads. I knew then that I was only wasting my time. I’d probably have to fight every one of them to get that bloody knife back again.

‘I must have made a mistake about the man I gave it to so,’ I said.

‘That’s right Dev,’ says your man.

When I told Maitias later what’d happened, he said that it was easy-known I was a ‘red-arse’ – a new recruit who’s still learning the ropes.

Sunday really dragged that first week, especially seeing as we’d no duty after the Parade Mass. I wrote a letter home telling them what things were like here, and then another one to Margaret. I spent the afternoon relaxing on the bed and I left very lonely thinking about Galway. With God’s help, it won’t be long before I’ve completed my stint here and we’ll be stationed back in Renmore. Patrick Connery here is actually a relation of Sean-Phádraig Ó Conaire, the writer, believe it or not. Signs on it too, he wrote an essay for the magazine Ar Aghaidh recently and it was as good as anything I’ve ever read in Irish. Myself and the Aran lad praised the essay to high heaven, but Maitias said that he thought that kind of work – reading and writing – is just stupidity and a waste of time really. It’s a pity I don’t have any small book with me here that I could pass the time with at night.

We were given our rifles the other day. They’re very heavy considering how small they look. We were in the storeroom and the Quartermaster handing them out, when he says:

‘Now young soldiers, take good care of these guns while you have them and you won’t go wrong. A soldier’s best friend is always his gun.’

Rattigan laughed sarcastically at this. ‘Not at all,’ he mutters under his breath. ‘They’re the friggin’ worst friend a soldier can have.’

We were given other stuff as well as the guns – a water bottle, a tin hat or helmet, a pack, a groundsheet and a handful of straps, two pouches and a wide belt to keep everything in. This is our equipment or kit and when we got back to the room, the red-haired fellow showed us how to fold the groundsheet properly and pack everything together. I could have been there till kingdom come for all I could manage it though. I just couldn’t get all the stuff packed together right. If I don’t have it done fairly well by tomorrow, the red fellow’s going to kill me, he says. Slowly but surely, our room’s getting fuller. Three other recruits arrived today, one from Cavan and another from Dublin, a lad by the name of Begley who seems very nice. The third lad is from Newcastle West in County Limerick and his surname is Hartnett. Begley has good Irish, but the other two lads have very little. The reason that they’ve been assigned to the Irish-speaking group, is that there aren’t enough Gaeltacht people joining as recruits, I think. These lads won’t be long getting comfortable speaking Irish, I’d say.

Myself and the lad from Cavan spent a good while chatting to one another by the fire this evening. He was telling me about the wild times he had when he was at college in Dublin before this, out drinking and pawning things to get money and all that. He hadn’t bothered with any study, he said, but this was what’d done for him in the end. Like me, he likes reading and he brought a book of English poetry with him from when he was in college. I felt sorry for him when I saw him trying his best polishing his uniform buttons with brasso. There was more brasso on him than there was on the uniform for a finish and so I’d to show him how to use the button-stick properly. Maitias says that he’s never seen anyone as awkward as this fellow in his life before. He said that watching us two was like watching a cat trying to teach a hen how to swim.

Maitias and Murphy have no bother keeping their uniform and clothes clean, but I’ve a long way to go to be as good as them in this department. I watched them the other day when they were polishing their shoes. The first thing they did was scrape the shoes with a razor blade until they were white as snow. Then they spread the red dye or ink out onto the shoe-leather and let it dry for a while. Next, they poured more red ink into a box of ‘Ruby’ and set fire to it. The ‘Ruby’ melted and mixed in with the ink, after which they applied this mixture to the shoes. If you’d seen the gleam on those shoes when they were done with them! I’m so bloomin’ awkward that if I tried the same trick, I’d have nothing, only red fingers by the end of it.

It’s great the way that we’re all getting to know one another and more used to one another’s ways in the room here. We were sitting around the fire tonight having the chat. You’d have sworn we all knew each other for years. It’s funny the way that both languages (Irish and English) are mixed together here too and the new lads trying to speak Irish, especially when they’re talking to the lad from the Aran Islands. Martin Cooke’s Irish is a bit different from the Irish the Connemara lads have also. He pronounces his words in a softer way somehow and his accent isn’t as strong as theirs.

Of course, there are differences in the Irish spoken between one village and another, back home in Galway. Even where I’m from, the Irish is slightly different from further west in Barna, or further back in Connemara too. The dialect in my homeplace, Knocknacarra is closer to Menlo-Irish or Claregalway-Irish, I’d say. I’ve met people from Inisheer over the years and I always thought that their Irish was Munster Irish really. For example, they pronounce the word mór (big) as múr. I picked up a good bit of Munster Irish when I was at school in Kilkenny and something happened tonight that proved this. Maitias was helping me put my kit in order and when he was finished, I said to him:

‘Gura maith a’d a Mhaitias, déanfaidh mé rud ort fós.’ (Lit: ‘Thanks Maitias, I’ll do something for you yet.’)

He gave me a confused look.

‘I mean that, “I’ll do you a good turn sometime”,’ I explained to him then.

‘Oh! You’d a right to say that in the first place. I thought you were threatening me or something! What you should really say in Irish is: ‘Déanfaidh mé rud duit.’ (Lit: ‘I’ll do something for you.’) But sure, there isn’t any good Irish where you’re from!’

Next thing Limerick poked his nose into it. He said that I was the one who’s Irish was correct – and that really put the cat amongst the pigeons, I can tell you! Next thing, the pair of them were slagging one another off with Maitias saying that Limerick, as with all the Munster crowd, had nothing only book-Irish really.

Maitias and I received letters from the girls today. They hand out the post at dinner-time in the canteen. As you’d expect, most of them were marked ‘Mr’ instead of ‘Private’ and the sergeant handing them out said: ‘There are no “Misters” here, please – only “Privates”. You leave your titles behind you when you come here.’

My letter was in Irish and Maitias’s was in English. It was written kind of funny really, even if Maitias couldn’t see the humour in it. You couldn’t say that there wasn’t poetry in it though. Here’s one sentence from his letter: ‘Sometimes I saunter up as far as the station, thinking that some wind will blow you down to me.’

Many Gaeltacht people have the habit of writing to each other in English, even if they always speak to one another in Irish. We spent a while drilling with our guns today. The guns are heavy, awkward-enough old pieces, to be honest. The red-haired Sergeant was on our case because we were so slow moving our guns when marching and every minute, he was: ‘Pull that bloody bolt towards you, ’83 McCauley! Stand up straight Hartnett!’ and all the rest of it. He has an ugly habit of dragging English adjectives into his Irish when he’s giving orders. His Irish is fairly fluent, but he always hesitates and has to think before he says anything – or that’s what I think anyway.

Daily life here is like school in some ways. It’s very regimented and everything is divided up along into the same time slots each day. A set amount of time is spent marching, learning in class, or maybe doing athletics or playing sport. I can’t swim and neither can the lad from Aran, but we were brought down to the baths today all the same. Everyone jumped into the water straight away, but I just stood on the edge of the pool, hesitating. Next thing the ginger fellow sneaks up behind me and shoves me into the water. Luckily, it wasn’t too deep and I managed a crab-like swim and got out of the water again. I felt really great after swimming however and on the way back for dinner, I was thinking quietly to myself. ‘Here goes now Dónall; now’s your chance to do what you always dreamed about since you were young – to be a soldier and to have good crack with all the other lads. Isn’t this a great life really? It beats working in the mill or even working in O’Neill’s hotel, good as it was.’

1Dev – De Valera

Chapter 3

We’re here a week now exactly. A week is just a short time and yet we’ve got to know lots of new people and learned new things. We received our wage packet today at half past one – we were only owed a half-week’s wages, but we couldn’t have been prouder the lot of us, as we walked up to the table to receive our pay. You have to take the money in your left hand and make a bowing motion with your right before turning sharply on your heel and exiting.

An old woman in a dark shawl and an old-fashioned black hat was sitting outside the front-wall of the barracks today selling sweets and fruit from a big basket. She’d a small donkey and cart from which she was also selling various provisions too. She’s a throwback to the old days, that’s for sure. They say that she’s been selling her wares from outside the barracks here since she was a small girl. Most of us couldn’t pass by without buying something from her and the minute we got paid, we all bought something off her – even though it’ll be time for dinner soon. Limerick didn’t bother going out to her, though. He’s thrifty and he went back to the room without spending so much as a halfpenny. Everyone’s entitled to their opinion, but if we were all that tight, the poor old sweet-woman would never make a living!

You’ve never seen the like of Big Reaney before in your life. He’d eat a rake of sweets and then go straight back out for more. Today’s a sort of a half-day really and we spent the afternoon playing cards or athletics; even if you don’t take part in the sports, you still have to go down to the playing pitches with the others so we were all marched down there after the two o’clock parade. A small group of us didn’t bother with sport and spent the rest of the afternoon wandering around. Cooke, Maitias, Limerick and myself; none of us have the slightest interest in sports or boasting about how good we are at them either – unlike some of the other lads here. Limerick is already old and worn-out from too much heavy physical labour. His joints are all so swollen and stiff that I doubt he ever played sport when he was younger. Tonight, when we were tidying up, ’06 Reaney whispered in my ear and we headed down to the wet canteen for a drink. You can’t buy pints in the canteen so we made do with bottled beer. A bottle of beer is sixpence. That’s a mark-up of one penny on every bottle – compared to buying beer out in a hotel or a pub outside somewhere. The place was packed with recruits, some of whom were drinking beer for the first time, I’d say. I had a real thirst on me as I’ve barely had a drink since I first started hanging around with Maitias. ’06 and I were birds of a feather though, and when the barracks orderly came in to close up for the night, the pair of us were still sitting there and nice and well-on-it, the same as the others there. We got to our feet straight away though and returned to our quarters in a nice orderly fashion as befits new soldiers.

Chapter 4

I was given three days C.B.1 today and it was stupid how it happened. We were just back in barracks after a spot of training on taking up positions. We’d to come indoors because it was lashing rain outside. It was fairly dark when we got back to the room, and the Sergeant reached for the light-switch to turn it on. The brass cover for the switch wasn’t back on properly because someone’d been messing with it this morning. And when the Sergeant reached over to it, the cover fell onto his hand and hurt him. I was closest to him when it happened and so he turned on me, those piercing eyes of his drilling right through me. ‘Who took the cover off the switch?’ he bawled out. And for some bizarre reason, it was right then and there that all good sense abandoned me. ‘Me’ I says, inexplicably. I don’t know what got into me, it must have been a rush of blood to the head or because I got a sudden fright or something. Whatever it was, I blurted this out anyway, and the lads stared over at me like I’d just lost my mind.

‘What’d you do that for?’ the Sergeant asks.

‘Just for the crack,’ I says, like the fool of long ago. You might as well be hanged for a penny as for a pound. Oh God! That’s when he went ballistic altogether! He stormed out of the room in a fury and wrote a charge out against me straight away. Next, I was ushered in to face the Company Captain for the second time since our arrival here and as you imagine, he didn’t go as soft on me this time. He read out the charge to me and said:

‘Guilty or not guilty?’

‘Not guilty, sir,’ I replied.