5,48 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: SAS and Elite Forces Guide

- Sprache: Englisch

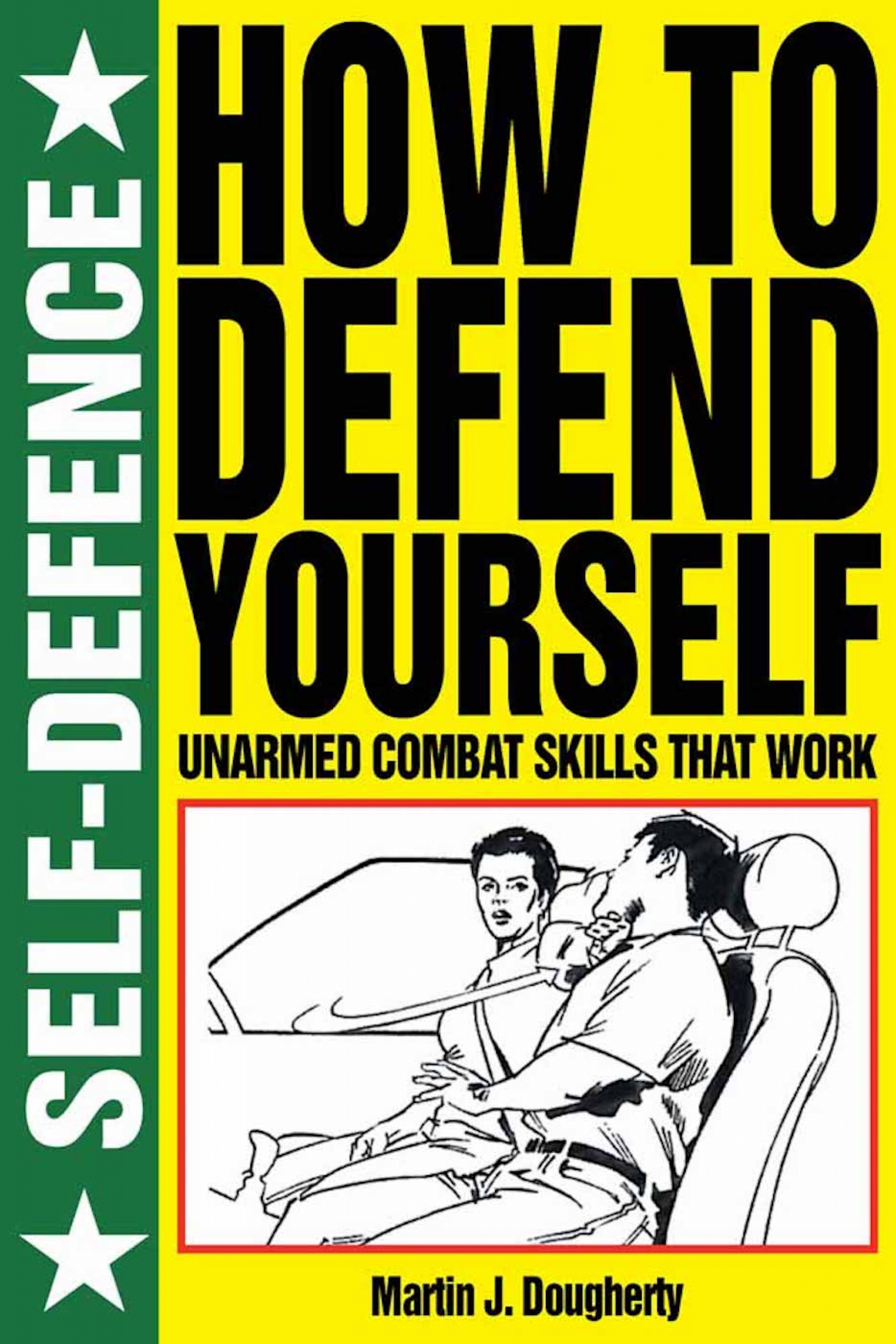

Duck punch, cover block and knee strike. Boxing, wrestling and Ju-Jitsu. Gameplan, lines of attack and final disengagement. If you can’t take flight, you’re going to have to fight. Extreme Unarmed Combat is an authoritative handbook on an immense array of close combat defence techniques, from fistfights to headlocks, from tackling single unarmed opponents to armed groups, from stance to manoeuvring.

Presented in a handy pocketbook format, Extreme Unarmed Combat’s structure considers the different fighting and martial arts skills you can use before looking at the areas of the body to defend, how to attack without letting yourself be hurt and how to incapacitate your opponent.

With more than 300 black-&-white illustrations of combat scenarios, punches, blocks and ducks, and with expert easy-to-follow text, Extreme Unarmed Combat guides you through everything you need to know about what to do when you can’t escape trouble. This book could save your life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 262

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

EXTREME UNARMED COMBAT

MARTIN J. DOUGHERTY

This digital edition first published in 2015

Published by Amber Books Ltd United House North Road London N7 9DP United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Instagram: amberbooksltd

Facebook: amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright © 2015 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978 1 782740 95 7

PICTURE CREDITS

All illustrations © Amber Books Ltd

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

www.amberbooks.co.uk

CONTENTS

Introduction

PART ONE: TOOLS

1. Basics

2. Defensive Tools

3. Striking Tools

4. Grappling Tools

5. Groundfighting Tools

PART TWO: APPLICATIONS

6. The Unarmed Opponent

7. The Armed Opponent

8. Firearms

9. Multiple Combatants

10. Distraction, Misdirection & Psychological Techniques

PART THREE: TRAINING

11. Physical Training

INTRODUCTION

Military, security and law enforcement personnel operate in an environment where extreme violence can erupt at any time. They often carry weapons, but weapons can be dropped, malfunction or run out of ammunition. When all else fails, unarmed combat skills can make all the difference.

The average police officer operating in a civilized area is less likely to encounter extreme violence than a soldier in a war zone, so for the most part we will consider military skills and applications. However, specialist police units such as hostage-rescue or Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT), anti-terrorist police and also those operating in unstable regions may well need to make use of the same kind of skills.

Police work can be dangerous, of course, and his uniform can make an officer the target for a level of deliberate violence not normally encountered by civilians. In this situation the officer may be fighting to survive rather than to arrest a suspect and, if so, may have recourse to some of the more aggressive skills in this book.

Law Enforcement

The line between ‘combat’ and ‘law enforcement’ unarmed combat skills is a blurry one at best. For example, Eric A. Sykes and William E. Fairbairn developed a system called Defendu, which is used as the basis of many modern unarmed combat systems. Defendu drew on experience gained in policing rather than military applications, but was then developed into a system to be taught to commandos and secret agents during World War II.

If suddenly attacked in close urban terrain a soldier’s ‘unarmed’ combat skills may be vital in creating space to use his weapon. His unarmed combat training also builds confidence and fighting spirit.

The similarly-named Defendo system was developed by Bill Underwood after World War II. His original system, named Combato, was an open-hand ‘combatives’ system for military applications and was extremely lethal. When asked to teach this system to law enforcement agencies after the war, Underwood instead modified it to create Defendo, which was less aggressive and better tailored to law enforcement requirements. Many elements were exactly the same in both systems.

Similarly the martial art of Krav Maga was developed as a result of its creator’s experiences fighting against Fascist gangs in the 1930s and was adopted by the Israeli armed forces. Variants have since been created for military, police and self-defence applications, all of which use the same basic techniques and concepts.

Depending on the circumstances, unarmed combat skills may be all that a soldier or police officer has at his disposal. They may also be used alongside a weapon. For example, a police officer may choose to employ his unarmed skills so that he does not have to use his weapon, and a soldier may have to use his combat skills in order to retain his weapon. This represents both sides of the same coin; unarmed combat skills give personnel an increased range of capabilities, and they are there when there are no other options.

Given all the other skills that police and military personnel must master, there is little time for training in complex martial arts systems. Some personnel do train in formal martial arts on their own time, but given that hand-to-hand combat is not the primary function of soldiers or police officers, the time available for ‘official’ training is strictly limited.

Thus military and police combat systems are a backup to other skills. They must be quick to learn and simple to use, yet effective under very difficult conditions. Whatever label is used – arrest and restraint, officer safety, close-quarters battle, combatives or hand-to-hand combat – the same factors apply. The system has to work quickly and completely; the opponent must be neutralized as fast as possible. Any other outcome can lead to disaster.

For most civilians, losing a fight can mean taking a beating, which is bad enough. For those who operate in a more extreme environment, defeat means death or capture. It can also lead to a failed mission and friendly casualties. Thus although unarmed combat is not the primary role of soldiers and police officers, they must be ready when it happens.

Law Enforcement Tip: It’s Not Like The Movies!

A real fight is never like a choreographed movie scene or martial arts sparring. It will always be a chaotic scramble; frightening, painful and desperate. Police officers and soldiers are trained to accept the reality that a win is a win, even if it looks like a scruffy mess.

Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) training is geared to a fair one-on-one fight with rules and a referee. It is, however, an excellent way to develop combat skills for any situation.

Martial Arts vs Unarmed Combat

It is impossible to say exactly when the term ‘martial arts’ was coined. Originally it meant something like ‘fighting skills’ and referred to life-or-death close combat. However, in the modern age the term has come to refer to a wide range of activities, some of them only vaguely connected with combat.

Some modern martial arts are useless for fighting. That does not make them worthless of course; they simply have other virtues and are often a worthy athletic endeavour in their own right. However, for those going in harm’s way as part of their occupational duties, these arts are of little value.

Other arts are more practical and often have real value in unarmed combat. However, it takes time to learn a martial art to the standard where it is useful in a fight, and along the way there are many hours spent learning skills that will never be used.

It requires long training to be able to make high kicks work in combat. For most personnel the time is better spent on other, less flashy, skills.

Special Forces Tip: The Red Light

Many military systems work on the concept of an imaginary ‘red light’. When the red light comes on it’s GO! GO! GO! until the threat is neutralized. The soldier must decide beforehand what will make the red light come on. It might be seeing an opponent’s fists come up or him reaching for a weapon, or it might be an order from a superior. Whatever the trigger, once the red light is on then the violence does not stop until the enemy is down and out of the fight.

For example, a sport martial artist will need to learn how to escape from a range of submission holds that a soldier on the battlefield is extremely unlikely to encounter.

With limited time available for training, the soldier needs to learn to deal with the most likely situations and to demolish his opponent fast rather than rolling around the floor for 10 minutes trying to apply an armlock. The converse is also true. A soldier or police officer trained in ‘quick and dirty’ unarmed combat methods would probably be defeated in a formal match with a trained mixed martial artist, kickboxer or judo player. Such a situation is beyond his area of expertise.

The fundamental difference between martial arts and unarmed combat training is that unarmed combat is 100 per cent geared towards the destruction or neutralization of the opponent. Restraints might be taught as part of an arrest and restraint package, but for the most part military personnel are trained to destroy their opponent, not merely defeat him.

Simple escapes from adverse situations, such as the ‘mount’ are a useful part of unarmed combat training. There is neither the time nor the need to get into the complexities of advanced groundfighting.

Where a martial artist might learn complex counters to an opponent’s martial arts techniques, the unarmed combat practitioner learns simple moves that will do maximum damage to the target. Not only is there little time for anything else, this is actually the most effective skill set. In an extreme environment, extreme measures are the key to victory.

Elements of military and law enforcement unarmed combat skills are highly useful for civilian self-defence. While the more extreme measures are not appropriate in most situations, a self-defence system drawn from military and police experience has much to recommend it. Not everyone has the time to study a martial art to a high level, and not all martial arts are effective for self-defence.

Military Systems

For someone who wants to achieve an effective level of self-defence capability without putting in endless hours, the military systems offer an indication of what works in a fight, and what can be quickly learned. This has led to the formulation of martial arts based around military principles. For example, the martial art of Krav Maga, based on the unarmed combat system of the Israeli armed forces, has recently become very popular worldwide.

There are also self-defence systems that draw on military and security experience. The Modern Street Combat system taught by the Self Defence Federation is not a martial art as such; it is instead a pure self-defence system drawing on aspects of military combative systems, martial arts such as ju-jitsu and traditional western fighting systems such as Catch Wrestling.

Conversely, elements of some martial arts are used by military and law enforcement personnel. Aikido and ju-jitsu are often used as the basis for arrest & restraint training as they have excellent joint-locking techniques. Other martial arts are used by the military for training purposes. For example, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) is used by the US military.

This is not because soldiers are expected to roll around on the ground with Taliban fighters trying to get a submission hold; that would be ridiculous. However, training in a competitive grappling system like BJJ allows soldiers to engage in a safe but extremely demanding sport that builds confidence and fighting spirit as well as being a hard workout. The benefits in terms of confidence and offensive mind-set are immense, even though the skills themselves are not all that applicable to the battlefield.

Thus some martial arts are of use to the military even if their specific skills will not be used. Others can be plundered for their most useful techniques or concepts. But when it comes to training soldiers to fight, martial arts are put aside in favour of a quick-and-dirty fighting system that relies on a few simple moves done with guts and determination.

Military and Security Applications

Slightly different skill sets are necessary depending on the situation. Security professionals (e.g. doormen and bodyguards) and police officers often need to get control of a person without doing them much harm, and have to remain within legal limits while doing so. Military personnel attempting to capture a prisoner for interrogation or who are using a low-level response to a threat may also make use of control and restraint techniques. This might happen when protecting an installation from an intruder who might turn out to be fairly harmless, or when deployed on a peacekeeping mission.

On the other hand, any of these personnel can be savagely attacked in the course of their duties. In the event of a lethal threat, extreme measures are justified. A police officer who loses his weapon in a struggle with a suspect and thinks the assailant is going to try to use it against him, or a soldier whose rifle jams in a close-quarters urban battle, needs to make an overwhelmingly effective response to the situation. There can be no half measures in this environment; often it is literally kill or be killed.

If a suspect suddenly begins resisting whilst being handcuffed, the officer is placed in a dangerous situation where he may not have time or space to deploy his weapon.

Bodyguard Tip: What’s Going On?

It is impossible to respond effectively to a situation without information. That means keeping alert and watching for anything out of the ordinary. Violence can explode at any time, but good situational awareness will give you enough warning to deal with it.

Special Forces Tip: It Ain’t Pretty

Military personnel are trained to take the best opportunity that presents itself and to attack whenever possible. There is no time for elegant technique or subtle countermoves. The aim is to demolish the enemy, not dance with them.

A number of stripped-down civilian self-defence systems exist, which apply the principles of military unarmed combat. Whilst care must be taken not to use excessive measures, the civilian who is facing a brutal beating by a gang, or who is attacked with the intent to cause death or severe harm, needs to be able to respond at an appropriate level. Effective self-defence training (as opposed to martial arts) is not very different to the military unarmed combat systems. Quick and dirty, simple and effective – that’s what works in an extreme situation.

Legal Matters

As previously noted, sometimes it is necessary for military and law enforcement personnel to limit the level of force they use in order to remain within the law. This applies even more so to civilian security operatives and private citizens who might need to defend themselves. The law permits anyone who fears for his safety to use reasonable and necessary force to protect himself.

The situation is not enormously different in a war zone. Soldiers are bound by international law and will answer for unlawful actions. The main difference is the sort of situation they are likely to encounter. Obviously, when fighting a declared enemy who is armed with automatic weapons, grenades and possibly artillery responding in kind is appropriate. In any situation where a soldier would be justified in firing his weapon, any unarmed combat move is certainly lawful.

Soldiers operating in a combat zone are not merely entitled to engage the enemy with whatever means they have at their disposal, they are usually required to do so unless it compromises a more important mission. This includes lethal force. In civilian life, someone who rendered an opponent helpless and then stamped on their head or choked them to death would probably be prosecuted for murder, but in a war zone finishing off an opponent is often acceptable. Indeed, it may be necessary to the mission or to the survival of friendly troops. A hostile who can get back up and attack again is a continued threat that cannot be accepted.

Law Enforcement Tip: Keeping Control

Most aggressors will only attack if they think the odds are good. Police officers are trained to control a situation so that a potential assailant does not get too close or move around behind them where they can attack on their own terms. Maintaining good awareness of the situation is essential to avoid being blindsided. Tactical mobility, changing position to keep potential assailants within the frontal arc, is an effective tool, but it is also possible to use obstructions to limit the opponents’ options. Police officers will also issue commands, such as, ‘Do not attempt to go behind me!’ or ‘Stay there!’ This not only asserts dominance over the situation but also informs the potential assailant that the officer knows exactly what he is up to.

Nor need the soldier worry too much about his level of force. If an enemy is trying to restrain the soldier to take him prisoner, or is trying to make an unarmed attack against an armed soldier, this makes little difference. What matters is that the target must be identified as a declared enemy whom the soldier has permission to operate against, and the soldier’s actions must not contravene international law. Executing enemy wounded or prisoners is murder, even in a war zone, but killing a sentry to prevent him raising the alarm is a necessary part of warmaking.

In short, military personnel are subject to ‘rules of engagement’, which dictate what targets can be engaged and in what circumstances. These rules apply whether the soldier is calling in an airstrike or engaging in unarmed combat. Decisions about whether or not to engage are made before the fight begins, possibly by the other side in the event that they initiate an attack. Either way, once in contact with an enemy who is determined to kill him, all the soldier needs to worry about is winning the fight.

Surrendering property in return for not being cut or stabbed is a reasonably good outcome. However, if the assailant tries to use the weapon, or attempts to abduct his victim, then the only option is to fight. A knife attack justifies extreme measures; anything less will fail, with fatal consequences.

PART ONE:

TOOLS

For most people, the possibility of encountering violence in their daily lives is remote. Crimes are committed of course, and disputes can escalate, but in most cases if we do not go looking for trouble, it is fairly unlikely to find us.

The chief reason for this is that there are those who are willing to go looking for trouble on our behalf. Soldiers may be sent to a conflict zone, or have to fight to protect our nation. Police officers will respond to an emergency call. These people voluntarily go in harm’s way to protect others. It is only right, then, that have at their disposal a suitable set of tools.

Many of those tools are physical, for example, firearms, body armour and communications equipment. Opposition will often surrender or melt away when shots are fired, or when it becomes obvious that armed force is about to be used. But there are other tools at the disposal of a soldier or police officer. Most of the time they cannot be seen, but they are there when there is nothing else. And that can make all the difference.

A good ‘ready stance’ is a starting point from which to move, defend or attack. It is extremely important to set yourself correctly – No Stance: No Chance.

1

Huge buildings are constructed on firm foundations. In the same way, a good set of combat skills requires a sound grasp of the basics.

Basics

When extreme violence erupts, you fight with what you have. In the case of a soldier in a war zone that can mean a rifle or machine gun, grenades, a bayonet and an assortment of heavy pieces of equipment that can be used to bash an opponent. Improvised weapons can be grabbed from the ground or the surroundings – it is possible to do a lot of damage with a rock, a stick, a spanner or a fire extinguisher.

However, sometimes a soldier will be thrown back on his own resources and must use his body for both attack and defence. This can happen for all kinds of reasons, for example, if hostiles have infiltrated a supposedly secure area to try to take a hostage or prisoner, or weapons might be dropped in close-quarters battle. With no time to arm himself properly, the soldier fights as he stands.

So what does he have at his disposal? What tools does the unarmed soldier or disarmed police officer have to save himself from attack? If he has been properly trained, he will have some lethal skills at his disposal and, more importantly, the will to use them.

Vulnerable Points

A soldier’s equipment may get in his way during unarmed combat, but it also greatly reduces the options available to an attacker. Body armour will stop or at least mitigate most blows, and there is no point at all in striking a helmet or a loaded rifle magazine.

Military combat systems must take into account both the encumbering nature of standard equipment and the lack of available targets. The face, throat and groin are all still accessible and are preferred targets for military unarmed combat. Not coincidentally, these are also some of the most vulnerable parts of a human being.

It is also possible to kick the legs or to try to break an arm, or to throw the opponent into the ground hard enough that he is injured by the fall. A downed opponent can also be finished off with the boots and, as a general rule, protection such as body armour is much less effective when a soldier is flat on his back being stomped on. A primary goal of most unarmed combat systems is to avoid this happening.

Special Forces Tip: Fight on your Own Terms

Special forces units are almost always outnumbered. They win by keeping the enemy off balance and confused. They fight on their own terms, not those of the enemy.

Principles of Unarmed Combat

The key principle of unarmed combat is the intent to do as much damage to the opponent as possible in the shortest time. There is no room for fair play, and dirty tricks are in no way dishonourable. Indeed, they represent a shortcut to victory and possibly the only chance of survival.

The most important thing a soldier takes into combat is a will to win and a willingness to hurt the opponent. He may not want harm anyone – most people, soldiers included, do not actually like causing suffering to others – but what he wants is irrelevant. What matters is what he must do in order to survive. Facing an enemy who is willing (and perhaps even eager) to kill him, the soldier must respond with the same level of aggression and violence or perish.

The combat skills an individual has, coupled with his strength, fitness and sense of tactics, are all tools that can be used to good advantage. They are, however, entirely worthless without a guiding will. A soldier who hesitates to strike a killing blow or panics in the face of extreme aggression is likely to lose. Thus military training fosters an aggressive mind-set, enabling the soldier to put aside other concerns and get the job done. It is this ability to get stuck in and dish out damage that will carry the soldier through a desperate situation.

In short, everything else depends on a willingness to fight.

Attack: the Best Form of Defence

As a general rule, being on the defensive leads to defeat. Martial artists and sport fighters can afford to play a subtle and clever game, drawing the opponent into making a mistake. A soldier has no time for that, even if it is likely to work. Instead he will take every opportunity to attack, overwhelming the opponent before he can act or help can arrive.

If he is aggressive enough, the soldier may not have to defend at all. Even facing multiple opponents, if he keeps moving and attacking he may confound their attempts to launch attacks of their own without actually defending as such.

Special Forces Tip: Defence

Defence is what you have to do when you screw up. If you’re being attacked then you’re not fighting on your own terms, you’re allowing the opponent to dictate what’s happening. That’s bad.

Any defence that is made must serve two purposes. Firstly, it must defeat whatever attack is incoming or at least mitigate it sufficiently that the soldier can survive it. He may be in pain or even need medical attention afterwards, but if he has defeated an opponent intent on killing him then that’s a win. Secondly, defence should not be purely defensive. Dodging a blow is of little value if the soldier gets hit again a second later, but dodging a blow and landing one of his own is a step towards victory.

Obviously, some defensive measures are necessary or the soldier will be taken out of the fight by anyone who succeeds in launching an attack of any sort, but the soldier must use an aggressive offensive-defence as much as possible and if he is forced entirely on the defensive (for example he is grabbed and held) then he must find a way to retake the initiative as fast as possible.

Stance and Movement

Many martial arts are excessively concerned about ‘stances’, many of which are unnatural and/or limiting in various ways. Whilst probably useful within their own environment, stylised martial arts stances are irrelevant to extreme situations. You do not win by standing around in an impressive stance; you win by doing something.

Most unarmed combat systems teach a basic ‘ready’ stance or guard position, but that’s all it is – a starting point. Once a fight starts the soldier needs to be moving constantly, aggressively advancing on his opponent and taking him out of the fight before moving on to the next target. A guard or ready stance is just a position you pass through on the way to doing something useful; it is not an end to itself.

The basic ready stance is not unlike a boxer’s guard. The strong hand (usually right) is kept back whilst the weaker one is advanced slightly. Hands are up and usually open rather than being balled into fists as this gives a greater range of options. Elbows are held in close to the ribs for protection. The body is turned at about 45 degrees to protect the internal organs. Feet will also be turned in slightly, with knees flexed ready to move. From this position the soldier can move in any direction and turn to face new threats.

Ready Stance

If violence erupts then the soldier will not spend much time in a ready stance – he will be far too busy attacking, moving or defending. Thus there are no points to be scored for a perfect ‘fighting stance’. All that is necessary is for the soldier to be able to launch powerful strikes, to avoid being hit or grabbed, and to move around freely.

Hands can be loosely curled or held as fists; it does not matter all that much so long as they are up and ready to strike or defend the head. Normally the strong hand is kept back and the weaker hand (usually the left) is advanced. This soldier may be left-handed, or may have switched to a ‘Southpaw’ or ‘Opposite-Lead’ stance for tactical reasons.

Keep Moving

Movement is the key to success and survival in battle. Constant movement makes the soldier a difficult target for unarmed attacks or anyone trying to shoot at him. It is important to move fast but to remain well balanced to launch an attack, so often a ‘shuffle’ style of movement is used. This maintains the guard position and avoids compromising balance by crossing the feet.

The Shuffle

Normally, we cross our feet when we walk, but this can make a soldier very vulnerable. If he is attacked in mid-stride he will not be able to react immediately, and his balance will be compromised. Most combat movement uses a ‘shuffle’ for this reason. A shuffle maintains the same lead, i.e. if the left hand is forward, it remains so.

Rather than stepping normally, the soldier pushes off with his back foot (B) and advances his lead foot, then brings his back foot up so that his feet are once again about shoulder width apart (C). Going backwards is the opposite; the front foot drives the motion and the back foot makes the step.

The basic principle of the shuffle is that it is all about pushing rather than stepping. To move forwards, the soldier drives himself with his back foot and lifts the front one just enough to make the step. Then he brings up his back foot so that his feet are once again about shoulder-width apart.

Backwards is the opposite; the soldier drives himself backwards with his front foot (this does not work well if he stands upright with straight legs; a slightly crouched posture with flexed knees facilitates rapid movement) and steps with the back foot, then catches up with the front one.

Law Enforcement Tip: Seize the Initiative

Police officers are trained to take control of a situation, to act rather than reacting to what the opponent does. They decide what they want to do, and then do it, forcing the opponent to try to catch up.

Diagonal movement and sidestepping use the same principle; the soldier pushes himself in the direction he wants to go, then moves his foot to that location. This is the opposite of normal walking, where the lead foot steps and the body then catches up.

Sometimes a soldier will take a normal step or run if it is appropriate. He might also dive, roll or jump as necessary. There are no hard-and-fast rules for movement in combat, other than this: however the soldier moves, he must get where he is going fast and ready to attack or defend when he gets there.

Aggression and Tactics

As already noted, pure defence does not win fights. It is necessary to do harm to the opponent and desirable to do it as early in the fight as possible. An opponent who is down and out of the fight cannot attack, which means that the soldier has successfully defended against whatever he might have done.

Simply piling into the nearest enemy can be surprisingly effective, but it is generally necessary to temper aggression with judgement. Where a soldier faces multiple opponents, the nearest may not be the most dangerous or the ideal target. It may be better to shove one opponent into another, neutralizing them both for a couple of seconds, in order to gain time to destroy a third.

Bodyguard Tip: Remember What You’re Trying to Do

Bodyguards are there to protect the client, not to win a fight with attackers. Fixating on one aspect of a situation can leave a dangerous hole in your capabilities, so be constantly aware of what’s going on and ready to respond to a new threat.

Striking and Grappling

Most military unarmed combat systems rely heavily on striking methods. This has some big advantages, notably that it will take an opponent out of the fight fast without entangling the soldier with his enemy. Sophisticated joint-locking techniques can be hard to apply in the middle of a fight, and the last thing a soldier needs is to find himself struggling with one opponent while another hits him from behind.

Thus ‘grappling’ techniques are secondary to striking techniques for all-out combat. Grappling is useful in certain circumstances, however. It can be used to control an opponent so that he can be arrested or captured, it can be used to disarm an opponent or break his limbs, and it can be used to silently kill an enemy who has been surprised or overwhelmed.

Grappling techniques are also frequently used in conjunction with strikes. For example, an opponent can be grabbed around the head, kneed in the body and then slammed into the ground to do further damage. Not only will this cause injury but it also puts the opponent in a position where he is extremely vulnerable.