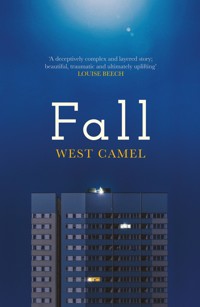

Fall: A spellbinding novel of race, family and friendship by the critically acclaimed author of Attend E-Book

West Camel

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Estranged brothers are reunited over plans to develop the tower block where they grew up, but the desolate estate becomes a stage for reliving the events of one life-changing summer, forty years earlier … the exquisitely written, moving new novel from West Camel. 'Unfolds like a spell' Carol Lovekin, author of Ghostbird 'A deceptively complex and layered story; beautiful, traumatic and ultimately uplifting' Louise Beech, author of This Is How We Are Human 'A mesmerising portrait of toxic family relationships: one that perfectly captures a turbulent era in a changing Britain. I was gripped' Caroline Wyatt _____________________________ Twins Aaron and Clive have been estranged for forty years. Aaron still lives in the empty, crumbling tower block on the riverside in Deptford where they grew up. Clive is a successful property developer, determined to turn the tower into luxury flats. But Aaron is blocking the plan and their petty squabble becomes something much greater when two ghosts from the past – twins Annette and Christine – appear in the tower. At once, the desolate estate becomes a stage on which the events of one scorching summer are relived – a summer that shattered their lives, and changed everything forever… Grim, evocative and exquisitely rendered, Fall is a story of friendship and family – of perception, fear and prejudice, the events that punctuate our journeys into adulthood, and the indelible scars they leave – a triumph of a novel that will affect you long after the final page has been turned. Illustrations by David F. Ross ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– **Shortlisted for the POLARI Prize** 'Fall's characters will haunt me, its story will stay with me and I will return again and again' Katie Allen 'Beautifully written, perfectly executed, a drama that captures your heart and mind' Anne Coates 'Architecture and morality: the only subjects worth writing about, and West Camel does so exquisitely through the eyes of people profoundly affected by both' David F. Ross 'A book about families, racism and the differences that bind us or push us apart …all bound up in West Camel's elegant prose' Michael J. Malone 'Suspense and twists keep you turning the pages, while the unfolding of complex characters and relationships draws you in' Valeria Vescina 'Both charming and conflicting … the author's enticing storytelling has totally, utterly hooked me' Sarah Sansom 'A page-turner and a literary delight, a book you devour' Liz Loves Books 'Immersive, beautiful, and haunting … I adored it' Live & Deadly 'A novel of mystic style and sensibility. West Camel tackles timeless themes of truth, power, family and justice … an extraordinary read' Richard Fernandez Praise for West Camel's debut novel Attend 'From its opening gambit to its final line, Attend demands and rewards attention' Foreword Reviews 'With its blend of dark, gritty themes and gorgeous imagery, this is a book to make you believe there's still magic in the world' Heat 'I've fallen in love with this absolutely glorious, spell-binding tale' LoveReading 'It's a genuinely pleasurable experience to encounter something couched in such alert and transparent language as West Camel's Attend … In three hundred finely judged pages, West Camel leaves the reader eager for more from his pen' Barry Forshaw, CrimeTime For fans of Sarah Moss, Bernadine Evaristo, Colm Toibin and Selina Godden

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 481

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

i

Twins Aaron and Clive have been estranged for forty years. Aaron still lives in the empty, crumbling tower block on the riverside in Deptford where they grew up. Clive is a successful property developer, determined to turn the tower into luxury flats.

But Aaron is blocking the plan and their petty squabble becomes something much greater when two ghosts from the past – twins Annette and Christine – appear in the tower. At once, the desolate estate becomes a stage on which the events of one scorching summer are relived – a summer that shattered their lives, and changed everything forever…

Grim, evocative and exquisitely rendered, Fall is a story of friendship and family – of perception, fear and prejudice, the events that punctuate our journeys into adulthood, and the indelible scars they leave – a triumph of a novel that will affect you long after the final page has been turned.

iii

Fall

WEST CAMEL

v

vi

Contents

1

From above, the city could be just another colour. A layer of lichen on bark. On a paving stone. Ragged-edged. Only slightly proud of the Earth’s crust.

But from lower down, a passenger bent into a window seat – while on the approach to Gatwick, Heathrow or City perhaps – might begin to see the tall buildings. From here they look like standing stones, arranged in the landscape according to some recondite scheme.

We can drop even lower, though, and now the estate by the river seems to be simply a haphazard grouping of shapes: rectangles and squares connected by the curved slips of roads, paths or bridges. Then a startling green swatch, dotted with pea.

Swoop still lower, and you might see that the various buildings are of different heights and in fact form a thoughtful pattern, giving each other space and meeting at purposeful angles.

And you might, if you trusted your wings enough to take you down even further, notice that the roofs are surprisingly pale and are topped with various boxes – sheds housing water tanks, maybe, or lift mechanisms and other plant.

And you might notice, on top of one building, what look like two dark glyphs; black letters that seem to be moving across the white page of this tower’s roof. And then you might glimpse what looks like a face, a grizzled head.

These are women, and one is beckoning to the other. They move to the edge of the page, and lean over the high, concrete balustrade at the top of this epically tall concrete tower, which beetles, in the words whispered by its architect as she bent over her drawing board more than fifty years ago, over the taupe Thames. You might see that they’re standing close together now. And you might even think you notice stress and concern in the tension of their bodies, in the way they’re pressed against each other, in the way they crane their necks to stare at something down below.

2

That something is – usefully for the beginning of a story – a someone: Aaron Goldsworthy.

Aaron has forgotten that the elevated walkway that leads from the parade of shops on Evelyn Street to the tower by the river is now partially demolished. The contractor’s fence, intended to prevent pedestrians using the walkway, was forced aside long ago, and he has stepped through the gap and reached the centre of the estate without once looking up from the envelope he holds in both hands.

He gasps and sways. Then breathes out in relief. Four more absent-minded steps and he would have fallen – not to his death; the walkway is only a couple of storeys above the ground – but certainly to a broken-legged, fractured-hipped inconvenience. He raises his eyes towards the tower by the river. He thinks of the greyed tarmac at its base, empty and dusty now.

He shakes his head a little. It’s lucky he looked up in time. He has no one at home to look after him, so an accident like the one he has just avoided would, no doubt, have led to an extended hospital stay. And in his absence he is sure there would be some form of bricking up, of dismantling, of cutting off of water and electricity. If he were hospitalised, and maybe even sent to some care home or other to recuperate, he may never be back here again, living in Marlowe Tower. With him gone, the last remaining resident of Marlowe, they could get on with redeveloping it.

The evidence of the estate’s transformation is all around him – in the half-empty blocks, clothed for the most part in scaffolding; in the chalky scars on the side of the community centre; in the rows of yellow skips that now occupy the school playground. In hospital, he knows he would find it impossible to resist any longer. But he’s not. So he can. He will refuse whatever new offer the council makes him. They have made three already.

Aaron pauses for a long time, just a few steps back from the broken edge of the walkway. Below him, in the large open area in front of what once was a parade of shops, a group of teenagers are spread out across the space occupied by the now-dry reflecting pool and the benches that surround it. They hop onto the low walls that form the pool’s sides, then push each other off. Shrieks and running. Aaron looks at the envelope again, at his name on the white sticker. Then down at the cracked grey surface of the ‘town square’, as his mother had always called it. The ruckled bed of the pool is filled with debris now – leaf dust, a fanned-out newspaper, a scattering of plastic clothes pegs. Aaron’s sight is not what it was, but somehow he can still see rubbish clearly.

Looking up a little he notes that about a hundred yards away, after the demolished section, the rest of the walkway is still standing, arcing through the estate towards the foot of the tower by the river, meeting it at the second floor. A ripped and ragged tongue of tarmac and concrete pokes into the damp air towards him, tempting him into a ridiculous leap. He takes another step backwards.

He looks at the envelope again and recalls seeing the walkway as a single, bow-shaped piece of white card, curving its path through the model in his mother’s studio. Clive picked it up once – one evening when they stalked, shoeless and giggling, into the room and stared at the blocks and towers, all a perfect Lilliputian white. The studio was forbidden territory. They were allowed entry only with express permission. Even gazing upon Zöe’s creations required her personal supervision, it seemed. Clive had glanced at Aaron, and, without a word, reached his arm over into the middle of the board and tested the walkway with his finger. Then, realising it was not stuck down – Aaron knew exactly what his twin was thinking – Clive clasped the slim piece of card in his curled fingers and lifted it. Stepping back from the model, he brandished the long card sabre at Aaron, sweeping it across his face and aiming its point at his eye, until Aaron hissed, ‘Stop it!’ and, careful not to damage the piece, prised it from his brother’s hand. He replaced it carefully on the thick cardboard cylinders his mother had crafted as supports, delicately pressing it down, tracing the length of its elegant curve through the scissoring blocks, over the town square with its pool, above the little parks, and finally to the tall tower on the riverside.

Aaron turns with closed eyes and makes his way back to the road and then, via the cramped alleys and awkward, dog-legged route created by the construction company, through the estate towards Marlowe Tower. As he approaches the town square again, he passes the windowless end wall of a block. The mural that was painted on it thirty years ago has been draped with a veil of green plastic net. It’s come away from one corner and hangs down, revealing part of the faded scene: a dirty-grey Marlowe Tower is recognisable, but it is oddly bowed, bending over a group of children with skin in a variety of flesh tones, but with faces that are flat and unshaded, and look out at the viewer rather than at each other. Aaron remembers the group of artists coming to paint it. Residents watching from their balconies with folded arms. Asking the artists to come and paint their kitchens. Do something worthwhile for once. This is worthwhile, Aaron once heard an artist retort. It brings everyone together. What if we don’t want to be brought together? came the reply.

The group of teenagers is still in the dry reflecting pool. Most of them are black kids. One white. Maybe two. One he thinks is Asian, but he’s not really sure. They’re clustered together now, looking at something in one boy’s hands. He wonders whether they’ve ever looked at the mural. He’s not even sure they live on the estate. He doesn’t recognise any of them. He wonders if they recognise him. The skinny white man with long grey hair who still lives in Marlowe Tower.

Past the town square he notes that one of the longest blocks is completely gutted now. The workmen have removed nearly all the windows and Aaron can see blooms of wallpaper in the exposed living rooms. Further on, though, another block stands as it always has: all the windows curtained; plants and bikes on the balconies; music pulsing out of an open door; its raw concrete still a proud cliff face.

But when he turns the corner by the school, he stops. Ahead of him is a view he’s never seen before. The workmen have demolished not only the long section of walkway that passes over the school, but also the spur leading from it, south towards the park.

But they haven’t yet toppled the sculpture.

It once stood at the end of the spur, on a circular platform, high above the stage of the park’s outdoor theatre. Now though, with the branch of walkway gone, it sits alone on an unscalable pillar. More than twenty feet of moulded concrete, its shape still eludes Aaron’s eye, and the grey sky behind it now makes it seem obstinate. Its base is a hollow drum, perforated by a lattice work of slots and apertures. Inside there’s enough room for a person.

Aaron wonders how they’ll bring it down. He imagines it hitting the stage below. The loud crack of the impact. The thought makes him jerk, and he hurries on his way, little reminding yelps travelling up his leg from his bad right knee.

Finally, after a journey made at least ten minutes longer, Aaron is sure, by the destruction of the walkway, he reaches the tallest building on the estate: the riverside Marlowe Tower. The name can now only be read in the paleness left behind where the letters have been removed.

Aaron heaves aside another contractor’s fence and pushes open the door to the service stairs.

On the second floor, he pauses in the main foyer, glancing out at the river through the wired glass of the vast window as he fruitlessly pushes the lift buttons. For a second – a tiny, hopeful second – he thinks he hears the homely clunk and hum of the lift mechanism waking up and sending the lift down to collect him. But no; it’s been weeks now since the contractor turned off the power to the communal areas. So Aaron heaves another of the many sighs of which his days are made, and begins the long, slow ascent to his flat on the twenty-fourth floor.

As he opens the door to his corridor, he is met by the gush of grey wind that has become familiar since the window at the other end was broken by some careless workman. But this time, along with the unvoiced breeze, comes a chirr and a thud. He stops, his hand keeping the door to the stairs open. The wind picks up and finds its voice: a quiet clarinet. He lets the door swing shut and listens again. Nothing. It was a piece of scaffolding rattling. Or some blend of draughts and pressures opening and closing a door in one of the empty flats above him.

Aaron pulls out his key and limps towards his flat.

As always now, when he arrives home, he tours the rooms, flicking all the light switches on and off to check he still has electricity everywhere. Then he turns on the taps, letting them run.

Finally he takes off his coat and stands at the living-room window, glancing alternately at the thicket of towers across the river on the Isle of Dogs, and at the envelope, which he has dropped unopened on the dining table. He has had to collect all his mail from the post office for weeks now; the postman no longer delivers to Marlowe Tower. Another way his path has been narrowed. He never opens anything until he gets home, though; he reads his correspondence in his own living room, as if refusing to acknowledge the tiresome daily trip. His old neighbours told him many times to get himself an email account, sign up for the internet. Perhaps he should have taken their advice. But that would have been cut off by now too, wouldn’t it? And no company would come to Marlowe Tower to install those wires and boxes. And he doesn’t have a smartphone – he barely uses the small mobile he keeps in a drawer.

He realises now that he has laid the letter on his mother’s place, and, for a moment – a moment when he thinks he should be opening it; a moment when anyone watching would wonder why he isn’t – he thinks of her. He imagines her long fingers holding the corners of the envelope and examining his name on the label, then turning it over and squinting, as if trying to read the print through the paper, before handing it over to him and watching, eyes avid with expectation.

Aaron takes a single, long step to pick it up. The stretch is unwise; his knee screams with the strain. But Aaron ignores the pain. He stands back at the window and hooks a finger under the flap. The envelope opens with a little cloud of white dust.

Inside: a single sheet.

The Residents’ and Tenants’ Trust

3 April 2021

Dear Mr Goldsworthy,

Many thanks for your letter of 12 March regarding the offers to purchase your home you have received from Deptford Borough Council.

The trust is already aware of the redevelopment of Deptford Strand Estate and of the proposed sale of Marlowe Tower to Clive Goldsworthy & Co. We have been assisting former tenants and owners of properties on the estate with their negotiations with the council, so we feel well positioned to advise you about your case.

In regard to your question about Compulsory Purchase Orders, we’d like to reassure you. It is not possible for a local authority to force someone to sell their home without good reason. If the local authority does apply to a government department (in your case, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG)) to gain the power to purchase your home without your consent, that government department will then have to make a decision about giving those powers to the local authority. Its decision will be based on whether there is what is known as ‘a compelling case in the public interest’ for the local authority to force you to sell your home, and whether the local authority has made every effort to negotiate with you on the sale. The local authority cannot force you to sell purely out of commercial interest.

In terms of your specific case, it is our considered opinion that the various commercial interests involved in the proposed sale and redevelopment of Marlowe Tower will make it difficult for Deptford Council to argue that there is ‘compelling’ public need for you to sell your home to them, simply for them to sell the entire building on to another party. The proposed purchaser, Clive Goldsworthy & Co., clearly wants to profit from buying Marlowe Tower, redeveloping the property and reselling the renovated apartments. The commercial benefit to Clive Goldsworthy & Co. could therefore be deemed as greater than any public benefit from the sale.

This case is further complicated by the fact that Clive Goldsworthy & Co. has also been contracted to redevelop the rest of Deptford Strand Estate. Our work with former residents of the estate, and with other interested parties, suggests to us that there may be several ethical questions around the relationship between the two deals: the contract to redevelop the estate, and the proposed transfer of the ownership of Marlowe Tower from the Council to Clive Goldsworthy & Co.

Overall, we believe that you would have a strong case against any CPO should Deptford Borough Council attempt to serve you with one.

We do stress that if you decide to make any challenge, you should only do so with the appropriate legal representation. We would also advise that any dealings you have with Deptford Borough Council should be done in cooperation with other residents or former residents of Deptford Strand Estate, and again with legal representation. We are coordinating a collective challenge to many aspects of the project, so would be happy to add you to the group of residents and former residents we are working with. We also have a team of advisers who deal with cases like yours every day. You can speak with one of them should you wish to discuss your case further.

Please keep us updated on your situation, and do let us know should you wish to join our efforts to challenge the development.

Kind regards

Sally Perry

Advice Manager

Aaron looks out of the window again, this time directly at the white tower that stands slightly apart from the cabal of heavy buildings where bankers sit in rows. This tower lacks their height but is tall nonetheless. And it is nearer the river, with a good view of the estate. Of Marlowe Tower. Of Aaron himself, perhaps. Aaron stares at the top floor. Is Clive there today?

He looks down at the letter in his hand, its white similar to the white of Clive’s tower. Not once does Sally Perry mention that Goldsworthy is both his name and the name of the ‘proposed purchaser’ of Marlowe Tower and developer of the estate. Did she wonder about this apparent coincidence as she composed this letter?

He lifts it a little closer to his face and reads a few phrases again. The tone is personal and impersonal at the same time. Studiously so. He puffs a little snort of air out of his nose. What does it matter how she says what she says? What’s important is that the letter tells him what he wanted to know – what he thought, in general, lumpen terms, was the case.

He turns and floats the single page onto the table; at this distance the paragraphs are dark, uneven blocks.

He sighs. He should be victorious, but instead he is sad. Sad and thirsty. And after his extended walk and the climb up the stairs, his knee is complaining. He shuffles across the worn parquet to the kitchen, pours himself a glass of water, then shuffles back through the living room and steps out onto the balcony, where he sighs into a metal chair, propping his leg up on another.

He drinks. Closes his eyes. A friendly breeze plays a little with his long hair. He threads it back from his face and behind an ear, and turns his eyes across the river once more, staring with what feel like unblinking eyes. He sits very still for a very long time. It’s as if, as his limbs relax, they set and harden, becoming immovable. As if he’ll never get up from this chair again.

3

Clive is in the tower. And it could be that he’s staring back at his brother. It could be that their eyes meet above the impermanent furrows of the river, where the tide is just at its turn.

But here, at Deptford Reach, the Thames is too wide for them to see into each other’s eyes. And Clive isn’t in his apartment on the top floor. He’s in his office, three floors down. And while he is at his window, he’s not focused on the pale smudge on a balcony on the twenty-fourth floor of Marlowe Tower.

They haven’t seen each other for forty years.

Clive’s look lingers on a spot at the very top of the tower. His fine fingers find the edge of the model that sits on a table beside the window. Unlike the maquette his mother made fifty years ago, only the tower on his model is in three dimensions. The rest of the estate is displayed as a plan. Shapes and zones in various shades. He stares at the grey of the real block, caught briefly in a flash of sun. His mother insisted that it stood at just that angle, at just that place on the riverbank, towering over Deptford Strand.

He glances at the model version of the tower – renamed for her. Reclad. The blunt top smoothed with a parabolic curve of roof, beneath which two, perhaps three new penthouses will offer views of the bristling city.

The curve is itself a tribute, mirroring that of the long walkway. On the model he can trace the path it once took from the road to the tower, threading through the narrow spaces between the old, long blocks, the open spaces and the town square, then flying over the intersecting curve of the estate’s main road before passing over the primary school, widening outside the health centre and tapering to a point as it arrived at the main entrance to Marlowe Tower. Home.

Clive has been informed the walkway has now been partially dismantled. The school is already empty. The health centre and community centre both closed long ago. The plan shows no trace of them.

Clive recalls creeping into his mother’s studio with Aaron, both trembling with mischief, the evening of the day her model was brought back to their house in Blackheath. The sun slid through the slats of the half-closed blind. The card and balsa-wood blocks cast neat shadows over the greens. The façades of the towers were lit gold. And the walkway’s sinuating journey was proud and prominent. It was a perfect little world. And that was surely the problem, he thinks now. It could only exist for a moment, when the evening sun shone in horizontal stripes and the tiny stick figures in the town square and outside the school and shops made grey letters on the impossibility of the white concrete.

Try as she might, even Zöe Goldsworthy couldn’t make full-sized, fleshy humans stand in the right places. And not even a Goldsworthy building could awe its inhabitants into living in a different way.

The glass door to Clive’s office creaks. A hinge hidden in the edge is misaligned, he thinks. Details, he thinks.

—Clive? says his assistant.

He turns. Kulwant has a folder in his hands. Papers to sign. Permissions. Instructions, Proposals. Somehow today, the folder looks limp.

—Do we have any news? Clive asks as he moves over to his desk, gesturing to Kulwant to take a seat.

—Yes, we do. Deptford Council just called. Kemi.

Clive looks up as he’s opening his pen.

—About Marlowe Tower?

—Mr… Kulwant coughs …Mr Goldsworthy refused the council’s latest offer.

—Of course he did.

He opens the folder and sifts through the pages, looking for yellow stickers, signing as he finds them.

—Did Kemi say anything else?

—Royal Mail hasn’t delivered to the tower for several weeks now, says Kulwant. Unsafe access.

—I suppose he’ll be collecting it from the post office, then.

Clive glances, just briefly, at the window. Even from his desk at the back of the room, he can see Marlowe Tower. And for a flash of a second he imagines what Aaron is doing. He imagines correctly, even though he doesn’t know it. Having rested his knee, Aaron has fetched a loaf of bread from the kitchen, and is now sitting at the table, buttering a slice. Clive doesn’t know that there are blue-grey streaks in Aaron’s hair.

—And there really is nothing else she can do?

—He’s still a resident, says Kulwant. The electricity and water firms can’t deny him services. She says the council has done everything it can to make things, well…

Clive taps the nib of his pen on his jotter. His irritation concentrated into the tiny tattoo. For Clive dislikes – intensely dislikes – having his plans thwarted. ‘Why must you always have your way, Clive?’ Zöe used to say, as Aaron folded his lips to hide a smile. ‘It’s so unattractive.’

Just once he replied, ‘For the same reason you do. Because I think my way is best.’ He had expected some slicing reprimand, but Zöe focused her pale-green eyes on his and said, ‘And you’re most probably right. What you need to learn is the trick to getting your way.’ She widened her eyes. ‘I’ll teach you one day.’

Now he nods, and tells himself that she knew him all too well. He must have his way, and usually does. But this time his brother is preventing it. He sits unmoving on the other side of a screen that they drew between themselves forty years ago. And if he doesn’t move, the meagre money Clive will receive, and major effort it will take, to renovate the rest of estate is for nothing. ‘Aaron’s obdurate,’ Zöe used to say. ‘Aaron, you are infuriatingly obdurate. You can never be persuaded of anything.’ Clive tried to tease his brother with the word, but Aaron seemed to quite like the label.

Clive taps his nib with such energy now, a drop of ink flies out and lands on his cuff. He raises his hand slightly in order to gaze at it as it soaks into the fabric.

—There’s a lot of other, non-Marlowe stuff to discuss, says Kulwant. There’s the cladding issue, of course. They’re not convinced by the specs for the new stuff. They’re saying that post-Grenfell they need more assurances. They want a meeting.

Clive doesn’t bother to stifle his sigh before saying:

—If there’s a space tomorrow, let’s meet them then. Make an agenda. Five minutes each issue. And have them come here. I can’t be bothered with the fuss of getting down there.

Kulwant has already pulled out his phone. Makes quick notes on the pad in his hand.

—Have we had any more questions from Knights about funding tranches? asks Clive.

—Not yet.

—I’m surprised; they’re usually over-punctual. They’re bound to call today. Don’t mention… Clive waves his ink-stained cuff … I don’t want them spooked.

Kulwant stands up, takes the file from the desk and makes the door creak as he leaves the room.

Alone, Clive moves back to the window. As if the light and air will help. He carefully places the fingertips of one hand on the model table, twitches his wrist so they hop and fall in a quiet drum roll.

It pains him to see Marlowe Tower still shabby, still brutally grey, still blunted. Still thinking it is the future, still believing it is standing above the docks and a river busy with tugs and barges, when all of that has gone, leaving it an unloved tombstone. He swivels, as if to make for his desk, as if to write this thought down. But instead he taps his fingers, more roughly this time. The model quivers so that the curve of the new roof shifts, and the tower now wears it like a jaunty cap.

4

This time Aaron cannot wait to get back to his flat to open the envelope. It’s brown, and when he sees the Deptford Council logo it’s all he can do not to tear it open in the post office. He refused the council’s last offer, and they acknowledged this refusal. Have they found some new way to force him out? It’s four days since Sally Perry asked about joining her ‘collective challenge’; he’s still unsure what his answer should be. Have the council now slipped in front of him? Clive always told him he was too slow.

But the queue in the post office fills every part of the tiny shopfloor. He doesn’t want to open the letter here. Out on the street is no better; the growl of slow-moving truck traffic would prevent him from properly understanding what he’s reading.

He nearly squeezes through the gap in the fence to take the footbridge over Evelyn Street, onto the walkway. But he remembers in time and crosses the road to take the disjointed path through the estate.

At last, at the foot of Marlowe Tower, it’s quiet and lonely enough for reading. He could wait and climb the stairs, he thinks. But no, he doesn’t want to be breathless and dizzy. He slips a finger under the flap.

Housing Development Team,

Deptford Borough Council

8 April 2021

Dear Mr Goldsworthy

We are writing to you to invite you to a meeting with our housing development team and with the proposed buyer of Marlowe Tower, Clive Goldsworthy & Company.

This meeting has been suggested by the company as a way to discuss the options around the sale of your property that would allow you to remain living in the area, and possibly on the estate or in Marlowe Tower itself.

Present at this meeting will be myself, Alexa Douglas, Kemi Olawale of the housing development team, representatives from Clive Goldsworthy & Co. and Holly Bridges of Hearst and Binfield Conveyancers. We are also inviting the other owneroccupiers still resident in Marlowe Tower.

The meeting will be held at our offices in Deptford Old Town Hall, New Cross Road, on 23 April at 3pm and will last approximately one hour. Please let us know as soon as possible whether you will be attending.

We look forward to your reply.

Kind regards

Alexa Douglas, Assistant Housing Development Manager, New Projects, Deptford Borough Council

The page flaps in one of Aaron’s hands; the torn brown envelope flaps in the other. Two questions have formed in his head:

Will Clive be at the meeting?

Who’s still living in the tower?

He drops his hands to his sides and looks upwards, scanning the windows of the tower. Here and there a scrap of left-behind curtain, a concertinaed blind.

He turns his head. He cannot see Clive’s tower from here. The view is obscured by the two plane trees that shade the riverside path. He notices, fleetingly, their divergence: one leans towards the water; the other reaches upwards.

He’s been so sure no one else is left. He has felt for weeks – for months – that he is the sole occupant. He has grown comfortable with it. It has become something he might wear.

Clive is behind this letter, he thinks. It may be from the council, but it bears all his marks. Aaron can almost catch the smell of his twin; a semitone away from his own; how he knew which was his shirt, his shoes, his golden tie.

He looks at the letter again. The writing suggests someone junior. He probably met Alexa when the team visited the estate. It was last year, after the first lockdown, he remembers. They set up tables and chairs under a marquee on the town square, he recalls. A small group of the remaining estate residents put on masks and sat in a safely scattered formation to listen to the council’s reasonableness. This was Alexa’s first job, he expects. One more than him, though. A hair licks his neck.

How many exchanges has he had with the council now? Double figures, it must be. And this is the first mention of anyone else in the tower.

He looks up again, fruitlessly. Then across the river once more. Has Clive installed someone in the tower? No – Aaron can’t make sense of such a move. He stuffs the letter into the envelope and makes his way to the service stairs.

He doesn’t bother pressing the lift buttons as he stalks through the foyer on the second floor, on his way to the main stairs. The intention hasn’t formed in his mind quite yet, but once he has ascended the first three flights to the third floor and taken the necessary pause, he sees the door to the corridor ahead of him, steps forwards and pushes it open.

He stares down the length of the corridor. The doors to the flats stand open. Pale rectangles of light lie like mats in front of each entrance. At the end, the window is cracked. No one on this floor.

On the fourth floor he goes through the same procedure: standing in the doorway to the stairs and registering the open doors of the flats, the wedges of colour inside. Only now does he wonder why the doors have been left ajar like this. In the past, an empty flat would be secured. Steel anti-squatter barriers fastened over the frames. But not here, not with Marlowe Tower. Why was no one interested?

Zöe’s declarations about housing trail after him up the stairs to the fifth, sixth and seventh floors. ‘People need homes,’ she would say, at dinner tables over wine, on the telephone. To him and Clive at breakfast. ‘Good homes. Ones we’d be happy to live in ourselves. And that’s why we’re moving.’

He’s struggling for breath now and has to pause on a landing between the eleventh and twelfth floors. He remembers Zöe’s hands on their shoulders in the lift the first time they visited the estate – they were still so young he didn’t differentiate between the hand on Clive’s shoulder and the one on his own – and her saying, ‘You’re both going to love it here. It’s a completely new way of living.’

It was a phrase they’d heard her use to anyone who frowned at the idea that she was taking her boys out of the elegant modern house she had designed, and down to the dirty banks of the Thames at Deptford, to live cheek by jowl with a woman who probably worked on the line at Peek Freans.

‘When I built the house in Blackheath, I said I’d be prepared to live in it myself, and I did,’ she would say. ‘And Deptford Strand Estate is the same. I’ll be proud to call a factory worker my neighbour. It’s a completely new way of living.’

The twelfth floor offers the same emptiness as the others. The new way of living is over. Aaron frowns. Did he say that out loud? He says it out loud:

—The new way of living is over.

His voice bounces off the concrete floor, the cracked render of the walls.

But there – is that a closed door?

His footsteps echo his voice as he walks along to the third flat on the right. Yes, closed. His stomach tightens. Stupid, he thinks. He spots the glint of the keep, halfway down the door frame. So the door’s not locked. What will he see if he pushes it open?

It takes some effort to raise his hand, brace two fingers and press them against the wood.

The door swings open, and Aaron is greeted by something very familiar. This flat has exactly the same layout as his own. He steps over the threshold, looks along the corridor and down the flight of steps to the bedrooms. Then enters the living room and stares around the dusty grey box. Yes, it is exactly the same as his flat twelve floors above. Only the angle from which he can see Clive’s tower is different. Fractionally.

Aaron taps his fingers on the gritty window ledge, glances at the walls: grimy Anaglypta. The floor – stains bloom; someone spilled something and let it soak through the carpet. He walks out and leaves the front door ajar.

He and Clive hadn’t been happy at first – to leave Blackheath, their garden. The view over the railway line from the back fence. The thick-trunked trees in the street. Their friends. But on that first visit, Zöe had promised them a glimpse of something secret. Something she had built especially for them. ‘A home is somewhere to play too,’ she’d said. And in one of the empty flats – pristine white and filled with the crunchy plaster smell – she’d opened a cupboard and pressed her fingers against one corner of wall at the back. A door had opened and Zöe had gasped dramatically, making them chuckle. Then she had passed through it, beckoning Clive and Aaron to follow. ‘You see how the flats are split-level – the living area on the higher level, the bedrooms on the lower one? Well the stairs in between create room for hidden passages. There are lots of places like these. And only the three of us know about it.’ Zöe had widened her eyes and her thick hair had fallen about her face, and in the dim light of the secret space she’d looked like the best kind of witch.

If she had really gone to the trouble of inserting all the ‘hidden places’, as she called them, just for Aaron and Clive’s benefit, then her plan had worked. Deptford Strand Estate was a vast playground built especially for them. They came to know every inch of it. Felt they owned every step and every alley. They’d gloried in it. And Zöe had gloried in their glory.

Re-entering the staircase, Aaron’s footsteps make a sharper echo. He takes the next flight with a little more energy. He got his breath back in the empty flat. But still he needs to pause on the next landing. And as he rests, does he hear his footsteps continuing to sound up the stairwell above him?

Or does he hear some other feet?

Now stopped. Just after his.

He moves on, but freezes on the third step of the next flight. Again, he hears it: an echo? Or other feet?

He recalls a game he and Clive used to play on this staircase. One starting at the top, on the thirtieth floor, the other at the bottom, they each attempted, by slipping into the corridors, to pass the other unseen. It was exhilarating – the scramble up the stairs to escape. The last-ditch attempts to wrestle himself free as Clive clung to his ankles. The stairwell had peeled with their screams. But it was quietly terrifying: the crowded-chest feeling he had as he craned towards the sound of Clive’s feet, trying to guess how far away he was.

Aaron blinks and twitches his mouth. How did he play it? By leaning heavily on the banister and treading as lightly as he could, he recalls. He tries it now. Reaches the next floor. And there, as he places a flat foot on the landing, he hears it. Hears them. Two steps. Two feet dropping one after the other. His heart breaks into a brief dance. He grips the banister, not to quieten his footsteps but to prevent himself sliding to the floor. He can’t seem to hear anything over the thump of his heartbeat.

How stupid.

But wasn’t this exactly how spooked he was by the game, back when he and Clive played it? He often gave up. Allowed his brother to catch him, so they could finish with the giddy grappling.

But how does this other person know how to play their game? Unless the other person is Clive.

No. That’s impossible.

Aaron has finally reached his own floor. He stops, listens; stops, listens. Then makes his way to his door. His opponent will win, it seems. Clive always won. He only ever played games he’d win. Games Aaron might win – the exquisite corpse, hangman – Aaron had to seek out Zöe for. Then Clive would move restlessly from room to room until Zöe stopped the game and said, ‘Go and play with your brother now, Aaron. Before he starts kicking the skirting boards.’

Aaron pauses at his door, fumbles in his pocket for his keys. As he pulls them out, he hears – distinct, clear, not playing a game, but moving with intent, footsteps passing quickly along a corridor somewhere above. Then the creak of a stairwell door swinging to. A pause. Then the slam of a flat door. The sounds form a little film.

He puts his key in the lock, and opens the door. Places the letter on the narrow shelf in his hall then goes back into the corridor, closing the door with the quietest of clicks.

Back at the stairwell he takes the flight with care but also with certainty. He’s no longer listening for someone playing a game with him, but for a clue as to which floor they might be on; which flat they have closed the door to. He checks floor twenty-five only briefly. He’s already presumed it won’t be that one; he’s lived in Marlowe Tower long enough to recognise footsteps directly above his head. The next floor he checks a little more carefully. All the doors are open. No one is here. The same for the twenty-seventh and twenty-eighth. And for the twenty-ninth. His breath is laboured now. A quiet dread somewhere deep in his belly has woken.

Floor thirty. A floor he has visited many times in the past. He pauses for a moment before opening the stairwell door. He looks through the wired glass and sees what he has been expecting – the regular rhythm of dark and light shapes on the corridor floor is interrupted here. One of the doors is closed.

He opens, passes through, and closes the stairwell door silently, then soft feet for all of the nine steps to the closed door of flat 304.

He stands in front of it. He thinks he can feel a kind of muffling warmth. The rounded scent of a body that’s just come by. He holds his breath. Yes, there’s a thunk, a pink, a shuffling drag from within the flat. Someone is inside. Doing indoor things. In the flat where Annette and Christine did their indoor things forty years ago.

5

The summer they met the twins, the sun had scorched almost to white the grey concrete of the blocks and towers, of the river terrace, of the town square, of the parade of shops. The grass of the verges and lawns had faded to yellow and then almost to ash.

Zöe had been jubilant. See how the estate has matured, she would say, almost every morning, calling in through the balcony door. Aaron and Clive would come across her with her camera, photographing the end of Evelyn House, where the stack of balconies gave the impression of a ziggurat cutting into the solid blue of the sky, or in the town square, where the reflecting pool was filled with water again. She had pressed and cajoled until the council had agreed to turn the taps on, and it had become a paddling pool, not just for the estate’s children, but the adults too, cotton skirts and old suit trousers hitched to the knees.

Smashing, Zöe had said as she expounded upon the weather, telling the ‘tourists’, as she called the colleagues who would make the excursion into Deptford to visit her, how perfectly the estate had responded to the new climate. How perfectly the residents had adapted to the heat. Smashing, she had said, as if the weather and her design were one and the same, or least came from the same source. Something high above. Smashing, she had said, each morning that had dawned early and hot, bringing her out onto the balcony in her voluminous kimono, to look down on her creation.

By the middle of June, Aaron and Clive had finished their A levels, and the rules Zöe had about her sons’ timekeeping had relaxed in the heat. University, for Clive at least, wouldn’t start until late September. They took full advantage, staying out late into the tropical nights. Zöe would make a little show of disapproval in the morning, but they caught her on the phone to their grandmother one Sunday: ‘They’re out to all hours these days. But I’m happy to loose the shackles.’ Clive raised an eyebrow at Aaron. Their freedom had been bestowed.

It was one such evening, as they came home from a party with old schoolmates in Greenwich, that they met Annette and Christine.

They had jumped off the back of the bus as it passed under the walkway on Evelyn Street, the conductor shouting back at them that the stop was just here, you daft ha’p’orths, then mounted the stairs and swung idly along into the estate, playing the game where they collided with each other every few steps, bouncing shoulders, doing it harder and harder to push the other off course.

As they reached the town square, the blocks on one side of the walkway still half lit and awake, music drifting from a couple of windows, and a dog splashing around in the pool below, his owner smoking shirtless on a bench, they noticed two figures approach them from the opposite direction. Two young women. They were dark with the walkway lights behind them, but then, as they came nearer, both with the same swinging gait, the lights from the town square below lit up their dark skin, their dark hair in coiled braids, their dark legs beneath their skirts.

It was rare to see black people on Deptford Strand Estate, Aaron remembers thinking. This part of Deptford, and Bermondsey next door, still hadn’t started to mix. And wouldn’t. Not for many years. He and Clive knew the estate inside out, and he didn’t believe a single black family lived there. But there was something about the way these girls walked – the easy slowness, the way their slim bodies occupied space – that suggested they were at home.

The women both smiled and slowed as they approached Aaron and Clive, parted as if to allow the brothers to pass between them, but then stopped.

—Twins! they shouted, in gleeful stereo. Then they put their hands to their ears and let out a tuneful scream.

The dog paddling in the pool below stood still in the water and let out a single bark. Its owner frowned at the little group of silhouettes he could see on the walkway, then shook his head, as if to say that the heat was doing funny things to people.

The twins’ scream spread across the estate, breaking in little waves over the sills of the open bedroom windows. Those that slept stirred without waking. Those still awake opened their eyes wider and held their breaths.

Zöe, who had dropped off just minutes before, woke with a start. She looked around, as if searching for the reason she was suddenly sitting up. Her mattress was on her bedroom floor. She had asked the twins to drag it out onto the balcony earlier that evening. She had seen people sleeping outside on hot nights when she’d visited Turkey and Lebanon, before they were born, she’d told them. But her balcony wasn’t big enough for a double mattress, so she had settled for sleeping beside the open door.

She stood up and stepped off the mattress and out onto the balcony, gazing over the constellation of fluorescent lights, squinting a little, as if she needed her glasses. She certainly couldn’t see Aaron and Clive, far off, over the town square, with Annette and Christine. She leaned against the concrete parapet for a moment, her face thoughtful, her eyes still half in sleep, then stepped backwards. As she did so, her polyester nightdress caught on the stipple of the raw concrete, pulling the fabric away from her body. She plucked it back with an irritated flick.

Turning back inside, she stood, slightly unstable, on the mattress and pulled the nightdress off over her head, before opening a drawer and pulling out a lighter, cotton one. But in the act of unfolding it to put it on, she froze, looking sideways at her reflection in the mirrored door of her wardrobe. She dropped the nightdress on the floor and turned her body at an angle, the blue darkness and blue light welling up the sides of the tower from the depths of the estate. She stretched out an arm and put her leg forwards. Then stood straight, her arms hanging by her sides. The swell and sag of her belly showed that she had had babies. She placed her palm on her navel. Was she thinking she might have more?

She shook her head and lay down, naked, on the mattress.

On the walkway, as the scream still spread in a rolling ring, the four figures at its centre, Aaron and Clive glanced at each other, with the same wide-eyed expression on their similar faces. On Aaron’s it was shy but amused; on Clive’s, surprised and challenged.

Aaron took two steps past the women.

—You’re twins too, said Clive, staying where he was.

—We are, said one.

—Annette, said the other, touching her chest. This is Christine. She touched her sister’s shoulder.

—I’m Clive, and that’s Aaron. Clive gestured almost dismissively towards his brother.

Annette and Christine had moved slightly along the walkway, towards the road, and Aaron had drifted in the other direction, towards home. Clive still smiled, still waited, intrigued. A little drunk. The line connecting him with Aaron had stretched, the gap had widened; between them stood this new pair of twins.

—You live in Marlowe Tower, don’t you? said Christine, pointing past Aaron.

—We saw you. Annette looked over her shoulder at Aaron, then at Clive. But we didn’t see you were twins until now. You dress yourselves different.

—So do you, said Clive, pointing at their gypsy skirts – Annette’s cream; Christine’s dark blue with lace trim.

There was a pause, everyone smiling in the warm darkness.

Both Aaron and Clive sensed they were outranked. These were women. No longer teenagers like them. Aaron moved another few paces towards the tower, and Clive was pulled an unwilling step in the same direction.

—Are you going home? Annette turned on the spot as he moved. Her eyebrows were raised.

Clive stopped again, as if she was challenging him.

—Where are you off to, then? he said.

—A party, said Christine. Then, directing her words down the walkway to Aaron: a late, late party.

—We’re just coming back from one, said Clive to Annette. Finished too early.

He looked over at Aaron. We’re ready for more, aren’t we? his expression asked.

—Come with us, then, Annette said. We’re only just starting. It’s not like you got school tomorrow or something. And she delivered a laugh like she was ringing a bell, throwing out a hand as if she held a clapper.

—I’m going to university in September, said Clive, a little too loudly.

—Time to celebrate, then.

Annette threaded her slim arm through his. Her smooth, dry skin made him feel damp and sweaty. And try as he might, he couldn’t stop the smile on his face giving him an innocent, eager look.

Aaron expected Clive to look back and check. They’d told their mother a vague time they’d be home. If they were going somewhere else, they should tell her a new time.

But Clive didn’t turn. He’d never not turned before. Aaron stayed where he was, his shoulders angled away from the other three.

It was Christine who turned. Even in the darkness her small smile told him she knew what it was to be the cautious one. She sauntered back. He couldn’t hear anything, but he felt she was quietly singing a song. She held out a hand towards him as she approached. And then, with a lighter touch than her sister, placed one hand on his forearm and moved it just a little, so she could put her arm through his.

—The best parties are in the middle of the night, you know. And anyway, you have to come now. We’re twins, you’re twins. I don’t know why that’s a reason for you to come with us, but it is.

A spritz of delight made Aaron grin. Christine grinned back even larger. She was impossible to refuse.

—Listen to my sister, Aaron. There’s no way you can’t come too.

Annette’s voice bounced along the walkway like a colourful rubber ball.

Clive looked back too. Christine was talking. Aaron attending, relaxed, in her care, in the curl of her smile.

They crossed over Evelyn Street, then tripped down the steps and into the park, the darkness here a hunter green.

—Where’s the party, asked Aaron, the empty vault between the trees oddly unfamiliar, seeming to hitch his excitement.

—New Cross, answered Christine, Annette saying the same a split second later, their voices juddering.

—At a friend of our landlord’s, said Christine.

—It’s his birthday. Annette produced an envelope from the fringed handbag that swung at her side.

—Fifty, said Christine.

—Fifty? repeated Clive, and stopped himself saying, we’re going to a fiftieth birthday party?

—Fifty, said Annette and Christine, and laughed as if it was funny. A dog barked somewhere out of sight.

The party was in a battered Victorian house in the centre of a short terrace, a remnant of the long rows that once spread among the confusion of railway lines between Bermondsey, New Cross and Deptford. The front door was open and the sash windows at the front were pushed up; silhouettes swayed across the nets inside, the music broadcasting from the bay and echoing off the long, low block of flats opposite.

People were draped over the front steps. And even now, Aaron and Clive can both remember the smell of grass – still rare then. Aaron can recall looking at the windows of the block across the road and wondering if the police might not turn up soon, if he and Clive shouldn’t turn tail. He must’ve caught Clive’s eye.

Clive saw Aaron’s face, flat and still, his eyes blinking, roving over the tableau on the steps, the man with the impressive afro, leaning against the doorpost. The twins surged up the steps – Annette pulling Clive with her; Christine and Aaron close behind. The man in the doorway nodded his afro low, smiling, and they pushed into the narrow hall, people lining the walls on either side. And Clive realised, just as Aaron did, that they were the only white people. Clive looked back. Aaron gave him a smile. The noise was warm. The heat loud.

—Ronald, called Annette.

Ahead of them, a man turned around.

—My girls. His rasping tenor cut through the music, and he put his arms out – one for each twin.

In the net of low lights from the various rooms, Clive saw the man’s fat dreadlocks, held back at the nape of his neck and falling over his shoulders as he bent to hug the twins.

—We’ve brought some new friends, said Annette, touching Clive’s arm. Christine pushed Aaron forwards.

—They live in Marlowe Tower, said Annette.

—And they’re twins too, said Christine. Look.

They lined themselves up either side of Clive and Aaron.

—A pretty picture, said Ronald, and held his hands up as if taking a photograph with an invisible camera.

—I’m Clive. Clive put his hand out to shake, trying to recover his confidence.

—Ronald.

—And this is Aaron. Clive put his arm on his brother’s shoulder. The muscle was taut.

—Welcome, boys, said Ronald.

—Happy birthday, said Aaron.

Clive realised in a rush that their hands were empty.

—Sorry, we haven’t brought anything. They … And the names escaped him for a second.

Aaron noticed before Ronald did:

—Annette and Christine, they only just invited us.

Annette spun round from a conversation she’d been having with a tall woman behind them.

—We found them coming home just as we were leaving, and decided to bring them. Twins, you see.

—Neighbours, said Christine.

—Don’t fret, boys, said Ronald. On my birthday, bring yourselves, and bring love, and that’s good enough for me.

He laughed with a hissed kissing noise. What he said had tickled him, but Aaron and Clive didn’t know why.

—Get yourselves some drinks, boys. Kitchen’s down there, said Ronald, his warm hand pushing Aaron gently towards the stairs. And then he turned, someone’s arm wrapping itself around his shoulders.