Fantasy Art and Studies 8 E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Fantasy Art and Studies

- Sprache: Französisch

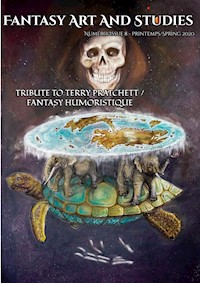

Ce 8e numéro de Fantasy Art and Studies rend hommage à Terry Pratchett, maître de la Fantasy humoristique. Introduit par un poème de Frejya Stokes, récipiendaire de la bourse Sir Terry Pratchett Memorial, il rassemble 8 nouvelles à l'humour ravageur signées par de nouvelles voix de la Fantasy française, et 4 articles analysant les oeuvres du maître et leurs adaptations. En bonus, retrouvez un entretien avec Patrick Couton, le talentueux traducteur français des Annales du Disque-monde. Le tout accompagné d'illustrations de Camille Courtois, Guillaume Labrude, Antoine Pelloux et Véronique Thill, et de la suite de la BD de Guillaume Labrude. This 8th issue of Fantasy Art and Studies is a tribute to Terry Pratchett, master of Light Fantasy. It is introduced by a poem by Frejya Stokes, recipient of the Sir Terry Pratchett Memorial, and it gathers 8 humourous short stories signed by new voices of French Fantasy, and 4 papers analysing Pratchett's works and their adaptations. As a bonus, read an interview with Patrick Couton, the talented French translator of The Discworld Series. This issue is illustrated by Camille Courtois, Guillaume Labrude, Antoine Pelloux and Véronique Thill, and it also features the new chapter of Guillaume Labrude's comics.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 291

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

EDITO

Sir Terry Pratchett a quitté ce monde en 2015, à l’âge de 66 ans. Il laisse derrière lui une vaste bibliographie, dont sa fameuse série Les Annales du Disque-monde qui a élevé la Fantasy humoristique au rang d’art. En tant que telles, les œuvres de Pratchett font partie des meilleures œuvres de Fantasy de la fin du XXe siècle et du début du XXIe. Sans surprise, elles ont imprimé leur marque sur la Fantasy actuelle, invitant auteurs et lecteurs à tourner en dérision les codes de la Big Commercial Fantasy tout en démontrant que la Fantasy peut être un miroir déformant de notre monde. Les univers et les personnages de Fantasy de Pratchett mettent en évidence les travers de la société occidentale, ses contradictions et les problèmes auxquels le monde moderne est confronté.

Les auteurs et les chercheurs de ce numéro hommage, introduit par un poème signé par l’actuelle récipiendaire de la bourse Sir Terry Pratchett Memorial, reconnaissent l’influence et l’originalité de la fiction de Pratchett, à travers 8 nouvelles par de nouvelles voix de la Fantasy française, qui rivalisent pour offrir d’excellents exemples de Fantasy humoristique aux personnages hauts en couleur, et 4 articles analysant les œuvres de Pratchett et ses adaptations. Les personnages de Catherine Loiseau regrettent le bon vieux temps où héros et vilains faisaient leur boulot correctement, dans un récit en accord avec l’humour de Pratchett. Caroline Duvezin-Caubet examine le recours aux notes de bas de page dans Les Annales du Disque-monde, soulignant que la vision et les idées politiques de Pratchett ne sont pas si progressistes. Dans la nouvelle d’Eric Morlevat, qui contient des notes de bas de page, un troll se révèle plus sage que les humains. François Bienvenu nous entraîne dans un monde régi par des magiciens pas si sages. Nicolas Auvray, pour sa part, s’intéresse à l’influence des règles algébriques sur le fonctionnement de la magie chez Pratchett, montrant que l’humour de Pratchett est souvent basé sur des théories scientifiques réelles. Par contraste, la nouvelle de Charlotte Efe fait appel à un humour pince-sans-rire basé sur la science des statistiques, tandis que Jordi Vila Cornellas nous emmène en Bretagne où des mages sont en compétition pour le poste d’archimage.

Au-delà de la magie et de l’humour, la fiction de Pratchett a aussi des liens avec le théâtre. C’est pourquoi Catherine Magalhaes et Maria Arvaniti examinent les adaptations théâtrales du Disque-monde.

Puis, Gabriel Féraud imagine un Seigneur Ténébreux confronté à une révolution sociale au moment même où ses troupes s’apprêtent à submerger le monde. Les personnages de Paul Vialart doivent assurément beaucoup aux membres du Guet d’Ankh-Morpork. Et Morgane, l’intrépide héroïne de Jonathan Jubin, est un bel exemple de femme forte et intelligente entourée par des pirates plus bêtes que méchants.

Enfin nous terminons ce numéro avec un entretien avec Patrick Couton, le talentueux traducteur français du Disque-monde, et le nouveau chapitre de la BD de Guillaume Labrude.

Bonne lecture !

Sir Terry Pratchett left this world in 2015, at the age of 66. He left behind a vast set of Fantasy works, including his widely acclaimed Discworld Series which has raised Light Fantasy to the level of art. As such, Pratchett’s works must be considered as some of the finest Fantasy works of the late 20th century and the early decades of the 21st century. Unsurprisingly, they have made their mark on current Fantasy fiction, inviting authors and readers alike to look at the codes of Big Commercial Fantasy with a humorous glance while demonstrating the potential of Fantasy to act as a distorting mirror of our world. Pratchett’s Fantasy settings and characters emphasize the foibles of Western society, its contradictions and the issues faced by the modern world.

The authors and scholars of this tribute issue, introduced by a poem by the current recipient of the Sir Terry Pratchett Memorial scholarship, acknowledge the influence and the originality of Pratchett’s fiction, with 8 short stories by new voices of French Fantasy, who compete to offer amazing examples of Light Fantasy full of colourful characters, and 4 papers analysing Pratchett’s works and adaptations. Catherine Loiseau’s protagonists mourn the good old time when heroes and villains did their job properly, in a story in line with Pratchett’s humour. Caroline Duvezin-Caubet examines the use of footnotes in the Discworld Series, observing that Pratchett’s vision and political ideas may not be that progressive. In Eric Morlevat’s story, which makes use of footnotes, a troll happens to be wiser than human beings. François Bienvenu introduces us to a place run by wizards who are not so wise. Nicolas Auvray, for his part, considers the influence of algebraic rules on the way magic works in Pratchett’s fiction, showing that Pratchett’s humour is often based on actual scientific theories. In contrast, Charlotte Efe’s narrative relies on a dry humour based on the science of statistics, whereas Jordi Vila Cornellas takes us to Brittany where three wizards compete for the archmage position.

Beyond the presence of magic and humour, Pratchett’s fiction also has links with theatre. Hence Catherine Magalhaes and Maria Arvaniti both examine the stage adaptations of the Discworld novels.

In turn, Gabriel Féraud imagines a Dark Lord faced with a social revolution at the very moment when his forces are about to submerge the world. Paul Vialart’s characters definitely owe to Pratchett’s Ankh-Morpork City Watch. And Morgane, the intrepid heroine of Jonathan Jubin’s story, stands as an example of a strong and clever woman surrounded by more stupid than dangerous pirates.

Finally we close this tribute issue with an interview with Patrick Couton, the gifted French translator of the Discworld, and a new chapter of Guillaume Labrude’s comics.

Enjoy!

Viviane Bergue

Sommaire

MIND HOW YOU GO

LE BON VIEUX TEMPS

FEET OF CLAY: FOOTNOTES AND AUTHORITY IN TERRY PRATCHETT’S DISCWORLD SERIES

À QUI, CE COIN DE PARADIS ?

HUBRIS OU LA COLÈRE DES MAGICIENS

SYMÉTRIES ET OPPOSITIONS LOUFOQUES DANS LES ANNALES DU DISQUE-MONDE

NOTE ELFIQUE N°537498 – PRÉSENCE IMPROMPTUE D’UN DRAGON

LE ZUGZWANG DE L’ARCHIMAGE

« LE DISQUE ENTYER N’EST QU’UN THÉÂSTRE1 »

HOLDING A WOSSNAME UP TO FANTASY: STAGING TERRY PRATCHETT’S WYRD SISTERS

LES ROIS NOUS SAOULAIENT DE FUMÉE

ENQUÊTE DE SENS

LA CHASSE AU TRÉSOR : ENSEIGNEMENTS ET FORTUNES DIVERSES

ENTRETIEN AVEC PATRICK COUTON

PROCHAIN NUMÉRO PROCHAIN NUMÉRO FABULEUX

POÈME

MIND HOW YOU GO

Freyja Stokes

Freyja Stokes was born in 1985, around 2 years after the publication of the first Discworld novel. Her lifelong love of Fantasy in general and the Discworld in particular has given her a permanently warped sense of humour, and also led to her becoming an early-career researcher at the University of South Australia where she is currently the Sir Terry Pratchett Memorial Scholar. Her research focuses on the Discworld as a framework for vernacular theory.

Freyja Stokes est née en 1985, environ 2 ans après la publication du premier roman du Disque-monde. Sa passion impérissable pour la Fantasy en général et le Disque-monde en particulier lui a donné un sens de l’humour tordu permanent, et l’a aussi conduite à entamer une carrière de chercheuse à l’Université d’Australie-Méridionale où elle est l’actuelle récipiendaire de la bourse Sir Terry Pratchett Memorial. Ses recherches sont centrées sur le Disque-comme cadre théorique vernaculaire.

The Internet has shared this image around, emblazoned with the words “we are the grand-daughters of the witches you could not burn” and … I like it. It has a neatness to it, it is accessible: a piece of portable rebellion I can fit in my pocket. Hell, it could even be true.

Maybe.

Probably not. But it does make a good story. And any witch worth her salt knows all about the power in stories. Stories are the intersection of patterns, and choices, and if you can learn to grasp them just right, stories can be steered.

So, I choose. Here and now, I choose to make myself the witch.

I am finally growing into my rage.

Hold me under the water and I will grow gills, will breathe deep so I can spit salt-water back in your face. I will not drown my voice for you.

Pile the kindling at my feet, I will strike the match myself and laugh as your crocodile tears and wrung hands blister from the heat. You will feel the force of my fire, my fury, and you will know fear. I will not char my skin for you.

I will pile the stones on my own chest. My heart has carried heavier burdens, has been crushed before. I will weave the winds to reinflate my monde ribs, call down lightning to jump-start the beating - my beating heart is a battle-cry and it will not be extinguished.

I am growing into my rage.

You taught me to fear the beast, the wolf, the woods. You told me to put my faith in the woodsman and never question why the first answer was always the axe, something that could be stitched up neatly with a moral and a monster, but I choose compassion.

I choose the kind of kindness that knows the difference between want and need, I choose to care enough to ask questions, to ask why you cast them as the monster in the first place.

I choose the kind of compassion that can be ugly, that can leave open wounds, but will always do first what needs to be done and damn the cost. I will balance on the knife’s edge and make those choices that need to be made. That is part of the job. I can stitch myself back together again when I am done.

I will walk through the woods, fearless, because I know that I am the scariest thing in here. And I will open my arms to my familiars, seek out a place for them where you cannot touch them with your cruelty ever again - you will have to go through me first, and I am learning how to make myself immovable. I am learning that “coven” is just another word for family, that “family” is the strength to say “enough is enough”.

So, enough.

Enough of keep calm, of be patient, stay civil, of play nice and bite your tongue. Enough of “smile for me sweetheart” when you don’t even know my fucking name. My name is a talisman. My heart is not sweet, and it is not yours for consumption.

Midnight has been hanging in my closet gathering dust for too long, but it was always there. I carried it from place to place, never intending to need it.

But now, at long last, I am growing into my rage.

I will take up the cloak and the hat, I will weave the stars into them and fasten them in place with the moon, and if it makes you feel better, well, you can call me bitch, call me crone, cunt, slut, hag, whore, whatever epithet you think will bandage back together your beliefs. Whatever lets you believe I am the boogie-man, whatever you think will banish your uncertainties.

I am not here to convince you to like me. I have work to do.

Call me witch. A witch’s job, after all, is to come when called. Our job is to see first what is actually there, and I want you to know that we see through your bullshit. But we both know what scares you most is that we see you for what you are.

Call me too big for my boots. Well, all that tells me is I need bigger fucking boots. These boots were made for digging in, for growing roots and refusing to take even one step backwards, refusing to yield ever again. We are witches, and we are growing into our rage, and we will not wither. Given time even grass roots can crack concrete.

We are growing things.

This is not your garden anymore and you are trespassing here.

You thought you planted weakness, but even flowers can kill you if you handle them without respect. You thought you planted control, but we are the fairy-tale woods, we are a forest, and a jungle, and wild things live here. We have flourished here in spite of you, and our roots run deep enough to hold us together.

And when the days grow long, and cold, we will pass down midnight, the hat, the cloak, the night sky, to our children, to our children’s children. They will inherit our world, our stories, not yours.

And we will tell them that midnight is their legacy, we will teach them how to draw down the winds and call up the seas, and how to care for growing things.

We choose this. We have chosen this. We have made ourselves the witches. We know all about the power in stories and we can make it true.

In time, our grandchildren will tell stories of witches, and of how we refused to be burned.

An Explanation (or “I can’t be having with this”)

Discworld fans will probably recognise a few pieces of imagery and turns of phrase in the poem above. That’s all well and good, but it doesn’t really explain why it matters beyond being a nod to a much-beloved author. To really explain how this poem relates to the work of Terry Pratchett, I first need to talk a little bit about the context in which it was written, so that means a quick tour of my childhood, my relationship to the Discworld, and to the Discworld’s witches.

I grew up surrounded by fantasy and science fiction, fairy tales, and most importantly, a lot of books that I had ready access to. I don’t recall when I first encountered the Discworld. It was, I think, somewhat before I picked up Pierce and probably after I had moved on from Dahl, but by the time I actually remember reading about Rincewind’s escapades I already knew the story. Of course, that could well be an artefact of how the Discworld itself is built out of culturally entrenched stories and folklore.

As a young and, by definition, foolish child I didn’t understand that you are not supposed to take stories seriously, or that fantasy wasn’t “real literature”. So, being the sort of child I was, and with the helpful indulgence of a parent who was happy to share their own love of “escapist” and “genre” fiction with me I devoured everything I could get my hands on (to the consternation of several of my teachers) and then proceeded to think about it very carefully1. As I grew up, I developed my sense of self, ideas about morality and justice and ethics, my understanding of the world at large, and the larger world in my own head, out of what I was learning. And a lot of what I was learning came from fiction. I could, in fiction, find and experiment with ideas and philosophies I couldn’t find anywhere else, and if I didn’t quite know what to do with an idea, I’d usually tuck it away to come back to later.

The Discworld has remained something I have come back to over and over again, and I still seem to get something different out of it every time. Lately I have been finding myself drawn to the witches, and to what they have to tell me about anger and choices. I think I can remember reading Equal Rites for the first time, though I’m not quite sure when that was. I’d like to say that it struck some chord within me, but mostly I was missing the series of (humorously) unfortunate events in the Rincewind books. It wasn’t until Wyrd Sisters that I really started paying much attention to the witches, and even that probably had more to do with the animated movie. Even so, Pratchett’s witches were a well-placed elbow in the direction that my perception of witches as characters and tropes in fiction developed.

Anger has been on my mind a lot in the last couple of years. There has been a lot for me to be angry about. But it was hard to shake the feeling that being observably angry was, somehow, wrong. As though no point would be taken seriously if not stated in it a soothing voice and from an artificially detached point of view. It’s a strange exercise to reconstruct what something meant to your younger self; the contemporary “you” has a tendency to creep in and re-arrange the mental furniture, so to speak. Looking back, I think that the witches of Lancre were my first encounter with the idea that anger is not something to be overcome or denied or resisted. Anger wasn’t an evil. It didn’t have to exist to the exclusion of empathy or compassion. It could be the appropriate response to a situation. And, importantly, under the right circumstances it could be useful. It has taken me a long time to wrap my head around that.

Like a lot of children, especially those who are raised as girls, I had grown up with the idea that strong displays of any2 emotion was inappropriate, embarrassing, and (worst of all) “attention-seeking”. Girls in particular are supposed to be “nice”, to be passive and self-effacing. We are supposed to want everyone to like us. Here I was as an adult, still subject to the social conditioning that had been ladled into my mind before I could make it up for myself. And I found that it was and is still a hard habit of thought to alter.

My latest re-read of the Discworld books has been a lot less casual than usual; I’m working on a project that requires me to comb through the books more methodically, and also to read and consider as much as I can of other people’s analyses of Pratchett’s body of work. It’s an enthralling process, full of side-tracks and fascinating connections, that I could spend a lifetime exploring. So, I guess I’ve been in the right headspace to start unpacking some of those ideas that I had put away for later. I was never very good at “nice”, though I certainly tried. I have, however, long believed in the importance of being kind. And I wonder if perhaps Granny Weatherwax might have been my first exposure to the idea that niceness and kindness are ultimately very different things. And how anger, when taken with the choice to take on responsibility, becomes fuel to effect meaningful change.

Right now the world is, both metaphorically and in many places literally, on fire. In the face of something that monumental, it’s easy to feel helpless. It can feel like we are staring down a foregone conclusion, like the story is set in stone. Our minds run on stories. So right now, I think we need witches. They remind us that things can be changed. That small acts of compassion are powerful. That we can choose to take up the role, if we put our minds to it. I’m a quiet person by nature; I’m not at home in crowds, or talking to strangers. Confrontation terrifies me down to my boots. Despite my best efforts, I am frequently still reflexively apologetic, and awkward, and anxious — and yet this poem was written to be performed, to be shared, and to be spoken aloud. Because there are things I should be angry about, and I am also no good at doing nothing. If I am going to be angry then I can learn from better minds than my own how to put that anger to good use. Because I can’t be having with this, so I guess I’d better start doing something about it.

1 A couple of decades later, and I have thoroughly refused to learn any better. As a result, I am now partway through spending several years writing an academic thesis essentially about how I was right all along. This, I have on good authority, is what many theses are essentially about, which is comforting to know.

2 But particularly stereotypically non-feminine.

FICTION

LE BON VIEUX TEMPS

Catherine Loiseau

Catherine Loiseau est née dans le Nord. Le virus de l’écriture l’a prise à 16 ans et ne l’a pas lâchée depuis. Elle s’est tout de suite orientée vers les littératures de l’imaginaire, avec une préférence pour la Fantasy et le Steampunk. Elle aime tisser des univers riches et créer des personnages complexes. Elle adore entremêler action et réflexion, aventure et humour. Elle partage ses loisirs entre l’écriture (bien entendu), mais aussi le dessin, la couture de vêtements d’inspiration victorienne, et l’apprentissage de l’escrime Renaissance italienne.

Catherine Loiseau was born in Northern France. She got infected by writing at the age of 16 and never recovered since. She immediately turned to imaginative fiction, with a preference for Fantasy and Steampunk. She likes weaving rich universes and creating complex characters. She loves intertwining action and reflection, adventure and humour. She shares her free time between writing (of course), drawing, sewing Victorian-inspired clothes, and learning Italian Renaissance fencing.

Azalphon contemplait le paysage par la fenêtre de son donjon et poussa un profond soupir. Il s’ennuyait ferme. Pas le moindre aventurier à l’horizon. Pas même un groupe de marchands à attaquer ou une troupe de gobelins à décimer. Le calme plat. Il soupira de nouveau. Sabrylyn releva les yeux de son grimoire et lui adressa un regard noir.

« Si c’est pour tirer la tronche comme ça, tu peux aller le faire ailleurs !

— Merci de ta sollicitude, » répondit-il à son épouse.

La sorcière se préparait à répliquer, lorsqu’un coup frappé à la porte l’interrompit.

« Oui ? » appela Azalphon.

Un homme entra, petit chétif, le teint verdâtre. L’un des assistants d’Azalphon.

« Maaaaître, un intrus a pénétré dans votre donjon. Il a massacré trois orques, avant qu’on arrive à l’arrêter. Nous le tenons prisonnier dans la salle des tortures !

— Eh bien quoi ? Qu’attendez-vous pour l’éliminer ?

— C’est que… il prétend vous connaître et il aimerait discuter un moment avec vous. »

Azalphon fronça les sourcils. Il s’apprêtait à refuser et congédier le domestique, quand Sabrylyn renifla d’un air méprisant.

« Ah, encore un de tes amis sorciers débiles qui vient picoler ! »

L’intervention de sa femme décida Azalphon à aller voir de quoi il retournait. Tout lui semblait préférable à la compagnie de cette harpie. Il suivit son assistant jusque dans les profondeurs du donjon, là où se trouvait la salle des tortures.

Au milieu des machines diaboliques et ustensiles en tout genre, les orques avaient dressé un chevalet. Un homme y était ligoté. Ses cheveux blonds tiraient sur le gris, son corps était couturé de cicatrices. Malgré son âge, il affichait toujours une musculature spectaculaire. Azalphon le reconnut immédiatement.

« Manar le Magnifique ! Ça faisait un bail ! »

L’intéressé releva la tête. Un sourire éclaira son visage.

« Je passais dans le coin, alors je me suis dit que c’était l’occasion de visiter ta tour. Dans l’temps, t’avais de chouettes trésors à piller.

— Dans le temps, oui, » convint Azalphon.

D’un geste, il congédia les domestiques. Il tira un coffre et s’assit à côté de Manar. Le barbare gigota pour éprouver la solidité de ses liens.

« Bravo pour tes gardes à l’entrée, ils savent comment ficeler un bonhomme. C’est dur de trouver des orques capables de nouer une corde correctement, de nos jours.

— M’en parle pas, soupira Azalphon. Mais alors, qu’est-ce que tu deviens ? Ça fait un moment qu’on t’a pas vu dans la région. »

Manar haussa les épaules comme il put.

« Bof, je voyage pas mal, je pille, je détruis les temples de divinités maléfiques, la routine, quoi. Et toi ?

— Les aventuriers, les sortilèges… Rien de nouveau par rapport à l’ancien temps. »

Les deux hommes restèrent silencieux et s’étudièrent. Manar avait vieilli, mais Azalphon devait reconnaître qu’il l’avait fait avec plus de classe que lui. Le magicien s’était empâté avec l’âge. Les longues robes noires qui mettaient si bien en valeur sa silhouette androgyne trente ans plus tôt le boudinaient maintenant.

« J’aurais jamais cru dire ça un jour, mais la belle époque me manque, le temps où toi et les sorciers maléfiques faisiez régner la terreur dans le coin, » avoua Manar.

Azalphon opina. Lui et le barbare s’étaient affrontés à maintes reprises, mais toujours dans les règles de l’art. Au final, Manar était devenu un très bon ennemi, plus fidèle et constant que les rares amis qu’Azalphon avait pu compter.

« T’as des nouvelles de tes compagnons ? demanda-t-il à Manar.

— Ermirol et Pram ont pris leur retraite y’a quelques années. Tormir est maître d’armes d’un des royaumes du sud. Hurn et Gorog sont morts en pillant la tour d’un seigneur noir, les risques du métier. Les autres donnent plus signe de vie.

— Et Ravenelle ? » s’enquit Azalphon.

La mention de la splendide et sulfureuse combattante arracha un sourire au barbare.

« Elle s’est mariée. Mais pas avec moi. »

Il ne put empêcher l’amertume de teinter sa voix.

« Et toi, tu louchais bien sur cette sorcière, Sabrylyn ? Vous arrêtiez pas de vous battre, mais personne était dupe, ça se voyait qu’elle te plaisait. Faut dire qu’elle était plutôt pas mal…

— Ben je l’ai épousée au final, et je crois que j’aurais mieux fait de la flamber sur place la première fois où je l’ai rencontrée. Heureusement pour toi qu’elle ne sait pas que tu es là. Sinon, elle t’aurait déjà balancé un « mort de masse ».

— Elle a pas changé d’un poil.

— Hélas non. »

À nouveau, les deux hommes marquèrent une pause.

« Les affaires, ça va comment ? » l’interrogea finalement Manar.

À tout autre que le barbare, Azalphon aurait répondu que tout se passait bien. Mais Manar était son meilleur ennemi, il pouvait se confier.

« C’est pas évident. C’est plus comme avant. Les aventuriers jouent plus le jeu comme vous. Je sais pas lesquels sont les pires, les petits jeunes qui débarquent sans aucune préparation et se font zigouiller à l’entrée, ou ceux qui étudient ton donjon pendant six mois, rentrent, évitent les embuscades, piquent le trésor et se tirent. Voilà des semaines que mes orques ont pas eu droit à une baston correcte. Toi et ta bande, vous m’auriez jamais fait un coup pareil. Vous tombiez dans les pièges, vous hésitiez pas à vous friter avec les patrouilles. C’était le bon temps, j’avais une vraie qualité de travail. Maintenant, tout fout le camp ! »

Manar opina. Azalphon remarqua alors combien il semblait fatigué. Des rides profondes creusaient son visage. Ses yeux bleus avaient perdu leur éclat.

« Tu sais, c’est pas facile pour les aventuriers non plus, ceux de la vieille école. Y’a les petits jeunes qui nous font de la concurrence, on doit rester au meilleur de notre forme pour pas être dépassés. Essaye donc de courir dans un couloir avec des rhumatismes ! »

Azalphon montra ses doigts déformés par l’arthrose avec une grimace compatissante.

« Les sorciers noirs, c’est plus ce que c’était non plus. De nos jours, n’importe quel clampin peut ouvrir une tour. Alors entre ceux qui sont trop faibles ou trop radins pour mettre des pièges, et ceux qui t’en collent à tous les coins de salle, c’est dur de bosser correctement. Je regrette le bon vieux temps, quand on pouvait parcourir un donjon et qu’on savait que le maître des lieux allait nous laisser nous battre un peu. »

Azalphon acquiesça.

« Je te raconte même pas les princesses ! Elles ne souhaitent plus être sauvées ! Elles parlent de prendre leur destin en main. La dernière que j’ai libérée m’a fichu une droite !

— J’ai arrêté d’enlever ces mijaurées depuis des années ! s’exclama le sorcier. C’est plus de tracas qu’autre chose ! Les succubes, même combat. Elles veulent plus servir d’appâts aux hommes, soi-disant que c’est dégradant. Les guerrières du Chaos refusent de mettre le bikini en métal traditionnel et réclament des armures, comme les orques. C’est de plus en plus compliqué de recruter du personnel de qualité. »

Manar opina.

« J’ai vraiment l’impression d’être devenu un vieux con, avoua-t-il.

— Non ! protesta Azalphon. C’est le monde qui est devenu con, pas nous. »

Il arracha un maigre sourire au barbare.

« Des fois, je me demande si je devrais pas raccrocher tout ça, avant de me rendre à l’évidence. L’aventure, je suis bon qu’à ça.

— Sabrylyn voudrait qu’on transforme le donjon en centre de vacances, mais moi je suis pas chaud. Je suis un sorcier noir depuis des années. Je tue les gens, je les massacre, je les torture, je fais régner la terreur ! J’ai pas envie d’accueillir des troupeaux de gamins !

— Comme je te comprends ! »

Un nouveau silence ponctua la conversation.

« Tu… tu comptes faire quoi, du coup ? demanda finalement Azalphon.

— Bof, je sais pas trop. Je pense que je vais continuer quand même l’aventure. Ça… ça t’ennuie pas si on se mitonne un petit affrontement à l’ancienne dans ton donjon ?

— Quoi, que tu te libères, que tu assommes les gardes et que tu retournes la tour ? Non, pas du tout ! Bien au contraire, ça me fera plaisir de combattre un adversaire à ma hauteur pour une fois ! J’ai un nouveau sort de boule de feu que j’adorerais tester. Sabrylyn va râler, mais je suis sûr qu’elle sera contente de te balancer un ou deux éclairs ! »

Le visage de Manar s’illumina à ces mots.

« Non ? Des boules de feu et des éclairs ! Oooh, vous êtes géniaux.

— Je te laisse te libérer, alors. Je dois organiser ma défense. Et s’il te plait, fais-moi honneur !

— Je n’y manquerai pas. »

Azalphon sortit de la salle de torture en sifflotant. Comme au bon vieux temps.

ARTICLE

FEET OF CLAY: FOOTNOTES AND AUTHORITY IN TERRY PRATCHETT’S DISCWORLD SERIES

Caroline Duvezin-Caubet

Caroline Duvezin-Caubet defended her PhD on neo-Victorian Fantasy in 2017 at the University Côte d’Azur (France). Her research focuses on speculative fiction (sometimes with a Victorian content, but not always) and she has published articles on twenty-first century Fantasy novels by Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman, Seanan McGuire and Heidi Heilig. She is currently teaching as an adjunct at the University of Poitiers.

Caroline Duvezin-Caubet est docteure en études anglophones de l’Université Côte d’Azur depuis 2017, sa thèse s’intitule « Dragons à vapeur : vers une poétique de la fantasy néo-victorienne contemporaine ». Elle s’intéresse surtout aux littératures de l’imaginaire (parfois sous un angle dix-neuvièmiste, mais pas toujours) et a publié des articles sur différents romans de Fantasy du vingt-et-unième siècle de Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman, Seanan McGuire et Heidi Heilig. Elle est actuellement ATER à l’Université de Poitiers.

“ Pterry’s footnotes are hit or miss. Some are hilarious, some are just unfunny. Usually the shorter they are, the better”: this comment from user raisindot, answering a discussion topic about readers’ “slightly mixed relationship” with footnotes in the Discworld books on a forum,6 constitutes an apt summary of how people react to Sir Terry Pratchett’s humour in his long-running series. The narrator’s tendency to digressions and non-sequiturs sometimes appears like a test of patience which can easily lose new readers; aficionados often have a preferred reading order to advise, and even for them, individual novels can be hit-or-miss. In that spirit, it seems wise to approach this distinctive stylistic feature of the Discworld series qualitatively rather than quantitatively: this article is structured around the close reading of only four footnotes which, while their selection was subjective, I believe to touch upon key features of the writing and worldview used throughout the forty-one novels.

Since the reader is likely to skip around and seek out the narrative arcs of individuals or groups, (like the very popular Watch novels), exploring the Discworld is not a linear narrative process, and neither is it straightforward on a linguistic level. Pratchett, who “[o] ccasionally […] gets accused of literature”,3 often plays around with the surface of the page, changing font sizes, depicting silence and staging either auditory or visual puns which are difficult to translate. Footnotes, however “genre-bending” they might be in fantasy as “a scholarly graphotextual device […] of seemingly foreign import”,4 at least come with familiar literary critical backgrounds like Gérard Genette’s work on paratexts in Seuils.5 However, these tools are not necessarily applicable to Pratchett’s light fantasy, as his meta-literary creativity lies more in the network of allusions that in obvious metalepses: he does not, for example, resort to the guise of a fictional editor annotating a found manuscript. The voice of the narrator remains constant between the main text and the footnotes, and if there is, as Shari Benstock argues, often “a discernible shift in the critical stance of notations […], a breakdown of the carefully controlled textual voice”,7 it seems quite subtle. I will however utilise and adapt some critical tools of science-fiction and several different theories on humour for the purposes of examining the mechanics of the footnotes.

Footnotes are read as harbingers of clarity, order and seriousness, a way to organise thoughts upon the page and not weight down syntax in the main text, striving for a classical purity of aesthetics. 8 This is diametrically opposed to the Discworld aesthetics, and, as will be shown through the different examples, this cultural connotation of the footnote is obviously turned on its head. Nevertheless, the footnote remains tied with authority through the figure of a writer, editor and creator distributing knowledge, however parodically. How does this spectre of authority interact with the poetics and politics of the Discworld?

On the Shoulders of Elephants: Worldbuilding and Encyclopaedia

The first two books stand as prototypes for the Discworld series: while flawed and not truly representative of the finished product, they are also a fascinating archive. Therefore, the first footnote analysed here is the first and only one in The Colour of Magic, located close to the beginning. Rincewind and Twoflower, who are riding away from Ankh-Morpork, are stopped by Bravd and the Weasel, who were watching the city burn:

‘Your pardon, sir–’ he began.

The rider reined in his horse and drew back his hood. The big man looked into a face blotched with superficial burns and punctuated by tufts of singed beard. Even the eyebrows had gone.

‘Bugger off,’ said the face. ‘You’re Bravd the Hublander,1 aren’t you?’

Bravd become aware that he had fumbled the initiative. […]

1 The shape and cosmology of the disc system are perhaps worthy of note at this point.

There are, of course, two major directions on the disc: Hubward and Rinward. But since the disc itself revolves at the rate of once every eight hundred days (in order to distribute the weight fairly upon its supportive pachyderms, according to Reforgule of Krull) there are also two lesser directions, which are Turnwise and Widdershins.