Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

During the early twentieth century, professional gamblers were such a scourge in the smoking rooms of trans-Atlantic passenger liners that White Star Line warned its passengers about them. In spring 1912 three professional gamblers travelled from the USA to England for the sole purpose of returning to America on the maiden voyage of Titanic. "Kid" Homer, "Harry" Rolmane and "Boy" Bradley (Harry Homer, Charles Romaine and George Brereton) were grifters with a long history of living on the wrong side of the law, who planned to utilize their skills at the card table to relieve fellow passengers of cash. One swiftly fell under suspicion of being a professional "card mechanic", and was excluded from some poker games, but other games continued apace. This new book, the result of years of research by George Behe, reveals the true identities of these gamblers, their individual backgrounds, the ruses they used, and their ultimate fates after tragedy struck, as well as providing an intriguing insight into a bygone age.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 271

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

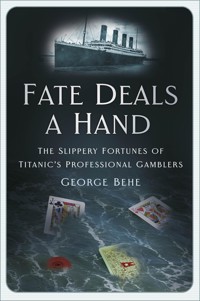

Front cover images, top: RMS Titanic departs Southampton on her maiden voyage (author’s collection). Bottom: White Star Line playing card and chip (author’s collection); other playing cards (spxChrome/iStock).

Back cover image: Text based on a White Star Line notice. (Author’s collection)

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© George Behe, 2023

The right of George Behe to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 237 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Titanic: Psychic Forewarnings of a Tragedy

(Patrick Stephens, 1988)

Lost at Sea: Ghost Ships and Other Mysteries, with Michael Goss

(Prometheus Books, 1994)

Titanic: Safety, Speed and Sacrifice

(Transportation Trails, 1997)

‘Archie’: The Life of Major Archibald Butt from Georgia to the Titanic

(Lulu.com Press, 2010)

A Death on the Titanic: The Loss of Major Archibald Butt

(Lulu.com Press, 2011)

On Board RMS Titanic: Memories of the Maiden Voyage

(The History Press, 2012)

Voices from the Carpathia: Rescuing RMS Titanic

(The History Press, 2015)

Titanic Memoirs

(three volumes, Lulu.com Press, 2015)

The Titanic Files: A Paranormal Sourcebook

(Lulu.com Press, 2015)

Titanic: The Return Voyage

(Lulu.com Press, 2020)

‘Those Brave Fellows’: The Last Hours of the Titanic’s Band

(Lulu.com Press, 2020)

The Titanic: Disaster: A Medical Dossier

(Lulu.com Press, 2021)

Letters from Titanic: Fine Press Edition

(The History Press, 2022)

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Prelude: Luodovic Radzevil and ‘Bud’ Hauser

1 The Gambling Techniques

2 The Non-Titanic Players

3 The Titanic Gamblers

4 On Board the Titanic

5 The Carpathia, New York and Afterwards

6 Jay Yates

7 The Three Surviving Gamblers

8 Gambler Legends

Appendix 1: ‘Old Man Jordan’

Appendix 2: ‘Doc’ Owen

Appendix 3: Harry Silberberg

Appendix 4: ‘Bud’ Hauser

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Several people were of great help to me while I was doing research for this book. Don Lynch, Philip Gowan, Mike Herbold, Hermann Söldner, Patrick Fitch and Brandon Whited all contributed important pieces to the puzzle, and I am deeply grateful to each of them for their assistance. Sandy Cottrell, reference librarian at the Macomb County Library, went to great lengths to obtain obscure 1912 newspaper microfilms for me, without which this book could not have been written. A special word of thanks goes to Bonnie Berg, who created the book’s pen-and-ink illustrations depicting the Titanic’s gamblers.

Finally, I owe a great debt of gratitude to someone I’ll never be able to repay. In September 1981 I first contacted Wallace B. Yates of Findlay, Ohio. Wally had carried memories of his conversation with Hanna Yates for half a century and very kindly answered the many questions I put to him. Wally and his wife Mabel travelled many miles in an effort to obtain new information about Jay Yates but were unable to find anything more. Wally’s own personal recollections were apparently the only ones extant in the Yates family, and it was with great sadness that, just two months after contacting him, I learned of his death on 2 December 1981, shortly after he suffered a heart attack. I hope my use of the information Wally gave me will, in some measure, repay the tremendous debt of gratitude I owe him. Mr Yates showed great interest in my project, and I hope he would have been pleased with the end result.

INTRODUCTION

It is a well-known fact that professional gamblers and con men secretly patronised the card rooms of transatlantic passenger liners during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and that these men often concluded their voyages in possession of more money than they started out with. The present author first revealed the existence of Titanic’s professional gamblers in 1982, when his article on the subject was published in the autumn and winter 1982 issues of The Commutator, the official journal of the Titanic Historical Society.

Unfortunately, in those pre-internet days serious researchers were forced either to borrow newspaper microfilms via interlibrary loan or else make personal visits to distant archives that did not participate in the interlibrary loan programme. The financial expense of making far-flung research trips severely limited the historical resources researchers were able to access in those days, and these informational gaps caused unavoidable historical errors to creep into Titanic books and articles that were being written during that period.

Times have changed, and nowadays electronic access to many archival collections has made it possible for researchers to rapidly sift through distant historical sources and uncover new information that otherwise might never have seen the light of day. This happened in the case for my ongoing research into the lives of Titanic’s professional gamblers, and I have taken full advantage of this present opportunity to correct a couple of historical mistakes in my original essay and add a great deal of new information that has come to light during the decades that have elapsed since its original publication.

This book is the author’s best attempt to present the definitive story of the three professional gamblers who survived the sinking of the Titanic.

George BeheGrand Rapids, Michigan, 2023

PRELUDE

LUODOVIC RADZEVIL AND ‘BUD’ HAUSER

The year was 1913, and Austrian barber Luodovic Radzevil found himself in dire straits when it became necessary for him to flee to England to avoid being conscripted into the army. After crossing the English Channel almost penniless, Radzevil began to evolve a plan whereby he could stave off starvation and perhaps even turn a tidy profit. The ex-barber must have had prior experience as a confidence man, because his scheme required such boldness and nerve that only an experienced practitioner of the art could have pulled it off.

Radzevil had learned his awkward, archaic English by studying a Bible. (Although its moral precepts were apparently lost on him, the Good Book at least made it possible for Radzevil to make himself understood.) Armed with this limited fluency in the language, Radzevil appeared at the White Star Line offices and offered his services as a steerage interpreter, claiming that he knew all the necessary European, Asian and African tongues.

The White Star official conducting the interview must have smiled sceptically as he asked the Austrian to say something in Chinese, but without hesitation the undaunted Radzevil asked the official to pose a question in Chinese so that he could answer it in the same language. Incredibly, on the strength of this audacious bluff, Radzevil got the job as interpreter for the White Star Line. His terms for employment were very simple: he wanted the equivalent of $10 in advance, a first-class passage to America and a blue uniform adorned with gold braid – and he received all three.

Using his cash advance, Radzevil instructed a printer to produce calling cards bearing his name and the title ‘official interpreter’. He then repaired to a holding area where emigrants were awaiting passage on a White Star ship and handed out his cards to these future steerage passengers. Although many people could not read the cards, they were suitably impressed and cowed by Radzevil’s resplendent blue uniform.

Next, the con man hurried to a nearby barber shop, where he determined the price of a haircut to be sixpence. Radzevil told the proprietor that a great crowd of customers would be arriving within the next fifteen minutes and would be presenting his ‘official interpreter’ cards. Radzevil instructed the barber to raise his prices for these people, charging two shillings per haircut and one shilling for a shave, and he specified that he would return later to collect 50 per cent of the barber’s inflated profits.

Rushing back to the holding area, Radzevil acquired a megaphone and informed the emigrants that the White Star Line required them to get a haircut and shave before boarding the ship, and for the next three days the barber shop was inundated with steerage passengers dutifully obeying the interpreter’s instructions. By the time it was over, Radzevil and the barber had both reaped a handsome financial reward from the transaction.

Next, the Austrian instructed the emigrants to visit a certain hardware store and purchase hunting knives as protection from the Native Americans who were rampaging in America, and the unfortunate people meekly followed his instructions. The interpreter was making plans for them to purchase new suits of clothing and visit a Turkish bath, but the White Star Line interrupted things by ordering the steerage passengers aboard ship.

Radzevil had planned ahead for this eventuality and is said to have had his cabin stocked with barrels of apples. The fruit was sold to his charges at two shillings each to supplement their diet of steerage food.

When the ship finally reached New York, Radzevil debarked with new luggage, a new wardrobe, hundreds of dollars and the names and addresses of 1,500 immigrants – but he was not finished with them yet. The interpreter rushed out and rented an office in Manhattan before hurrying back to where the immigrants were awaiting clearance through customs. Addressing the crowd, Radzevil informed everyone that he would continue to work for their well-being in the United States and that if anyone wished to send money back to the Old Country, he would be happy to arrange the transaction. Radzevil also promised to arrange a military service exemption for anyone who wanted it (even though America had no draft at the time).

As the months went by, many of the immigrants came to Radzevil’s office to take advantage of his generous offer of help and entrusted money to him for transmission to relatives in Europe. When they later enquired why the money did not reach its intended destination, the wily Austrian blamed the mail service and implied that greedy mail clerks were stealing the funds. To allay suspicion, Radzevil carefully kept track of his customers’ losses and promised that his friend the president would assist him in the coming investigation.

This lucrative arrangement continued for several years until, by chance, the Austrian Consul got wind of the situation and informed the postal authorities, who quickly brought Radzevil’s career to a close.

*

The story of Luodovic Radzevil’s lengthy confidence game was first presented in a book by Jay Nash titled Hustlers and Con Men, but this kind of prolonged bilking of victims was not a usual feature of the typical shipboard bunco game. Most con men who operated on the great passenger liners brought their game to an end at the termination of a voyage, thus facilitating a quick, clean getaway with their ill-gotten gains. In addition, these grifters rarely attempted to cheat passengers in steerage and instead preferred to target rich passengers in first class, a practice that usually netted the con man a much higher profit margin in return for his time and effort.

The simplest way for a bunco artist to achieve his goal was to engage a potential victim in a dishonest game of cards. The smoking rooms and private cabins of the ocean greyhounds were usually the settings for these card games, and those belonging to the White Star Line were no exception. In our examination of these professional gamblers, let us leave Luodovic Radzevil and go back one year to 1912 – a year that several sharps would always remember and a year that brought the career (and life) of at least one other seagoing professional gambler to an abrupt close.

When B.J. ‘Bud’ Hauser boarded the Olympic at Southampton on 3 April 1912 he undoubtedly intended to arrive in New York with more money than he set out with. (He had done it many times before, the Olympic herself having been the setting for six prior coups.) Hauser was a man accustomed to living by his wits, and – had fate not intervened – this voyage might have proved just as profitable as the others. You see, Bud Hauser was a ‘sporting man’, a euphemism used early in the twentieth century to denote a professional gambler and confidence man.

Like many a sharper, Hauser made his living on board the ocean greyhounds and, by spending his evenings at cards in the smoking rooms, he could usually relieve unwary passengers of any superfluous cash they might be carrying. He was good at it, too, because his fine appearance and hearty manner served to disarm anyone who might suspect him of less-than-honourable intentions.

But Hauser’s wholesome demeanour was just the masquerade of a first-rate card mechanic. It was he who originated a novel method of cheating at bridge when the game was still new. (Hauser engaged a New York millionaire in a ‘friendly’ game but stationed a confederate in such a position that the millionaire’s hand was visible to him; the confederate, by the way he smoked his cigarettes and the drinks he ordered, conveyed information to Hauser about the victim’s cards, and the millionaire walked away from the table $60,000 poorer but perhaps a little wiser.)

B.J. ‘Bud’ Hauser.

Of course, Bud Hauser did not become a consummate con artist overnight. He was born in New York around 1874 and was one of three brothers who were taken west when they were very young. In 1894 Hauser returned to New York as the possessor of very definite sporting tendencies and brought with him a string of horses. Aided by a stable badge, he posed as an authorised betting commissioner – a ruse that continued until the Pinkerton Agency told him he was barred from all metropolitan racetracks.

After this setback, Hauser concentrated on improving his digital dexterity and developed a reputation as an excellent card mechanic and con man. After he began to travel outside New York he was arrested in Chicago for swindling a man out of $4,000. In 1900 he was back in New York and formed a temporary partnership with his brother George, and together they lured a man off an ocean liner and took him to Kid McCoy’s saloon. There they administered knockout drops to the unsuspecting pigeon and robbed him of bonds valued at $3,000. Hauser was eventually picked up by the authorities but was discharged when it was learned that the victim had returned to Europe.

At various points during his nefarious career Hauser was arrested on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1902 he was accused of a robbery in New York but was released on $3,000 bond. He promptly dropped out of sight and, for the next six years, he succeeded in eluding the district attorney. In 1908 he finally slipped up by assaulting a man in the café of the Waldorf-Astoria, which led to his capture on the old charge of jumping bond.

In December 1908 Hauser was arrested once again on Broadway after advertising in the newspapers (using the alias McCafferty) that he would give tips on the horse races and pick a winner every day.

At about this time he began to travel the ocean liners utilising his expertise in card and dice manipulation. On 31 December 1910, upon the arrival of the Cunard liner Campania, Hauser was arrested as a dice swindler.

Despite his many arrests, Hauser actually spent very little time behind bars. In fact, his friends all claimed he was never convicted of any crime, even though he was often apprehended and accused. Hauser had good looks and a hearty, breezy manner that seemed to make his victims reluctant to appear against him in court, and so the gambler’s sea-going career flourished. He often teamed with other ‘deep-water men’ like W.J. ‘Doc’ Owen, Colonel Torrey (Willie Green), George McMullen and Frankie Dwyer, and these confidence men would divide up the spoils of war at the conclusion of each voyage.

Hauser usually booked onto a ship using the pseudonym ‘Barton J. Harvey’, letting it be understood that he was a son of the Harvey who founded the system of hotels and cafes on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroad system. Byron J. Harvey, the true son of the restaurateur, was well aware of Hauser’s use of the family name; indeed, ‘Barton J. Harvey’ was often mistaken for Byron Harvey due to the similarity in names, and the gambler did nothing to discourage this confusion.

Hauser was using the Harvey alias on his 3 April 1912 trip on board the Olympic, and the voyage to New York was proceeding smoothly. He was described as the liveliest man in the smoking room and caused much comment by the ‘reckless’ way he played cards and the great diversity of his alcoholic refreshment (absinthe, straight rye whiskey, champagne, and more). He also made a daily visit to the ship’s Turkish bath, perhaps attempting to blunt the after-effects of his nightly revelry. Every evening at around 9 p.m., however, our man would abandon the social atmosphere of the smoking room and retire to the privacy of his stateroom. It was rumoured that he and several other passengers played cards there until the wee hours, but no detailed information is known. It was later claimed that on the first day of the voyage Hauser and his fellow grifters fleeced Olympic’s passengers of a sum approaching $10,000.

On the evening of 9 April 1912 Hauser, as usual, had been drinking rather immoderately, and as 9 p.m. approached he lay down his cards and left the smoking room. After stopping off to enjoy another brief session in the Turkish bath, he retired to his stateroom. What happened to him after that is uncertain, and it is possible the facts were deliberately obscured by the gambler’s colleagues.

In the stateroom next to Hauser was a man who booked on the passenger list as ‘A. McClellan’. At about 5 a.m. the next morning, when Olympic was 150 miles east of Ambrose Channel, ‘McClellan’ said he heard a commotion in Hauser’s stateroom followed by the sound of a man groaning. He arose and went next door, where he found the gambler tossing around on his bed with a cold breeze sweeping through the room. ‘McClellan’ called a steward, who immediately notified ship’s doctor J.C.H. Beaumont. Upon entering Hauser’s stateroom, Dr Beaumont found his patient lying in his berth dressed only in his underclothing, semi-conscious and groaning from the severe pain in his heart region. Stimulants were administered to the stricken man, but they had no effect. The physician remained with Hauser until 7.55 a.m., at which time the gambler expired. It was said that three other professional gamblers who were on board Olympic were acting as nurses in the stateroom when Hauser died.

When word of Bud Hauser’s death leaked out, rumours raced through the Olympic’s company like wildfire. One of the most common stories was that ‘Barton Harvey’ had lost heavily at cards to a group of professional gamblers (!) and had died of a heart attack in his stateroom. Another story claimed that ‘Harvey’ had won a large amount of money from several gamblers and was so slow to pay the debts he had incurred earlier that the gamblers attacked him in the smoking room, after which he retired to his stateroom and died of his injuries.

When the Olympic docked in New York on the afternoon of 10 April 1912, the ship’s officers denied these rumours. Dr Beaumont reported that ‘Harvey’ had died of ‘heart disease following alcoholic poisoning’. The physician even sent a telegram to the Harvey family notifying them of their ‘son’s’ passing, and detectives employed by the White Star Line went aboard the Olympic to investigate the death.

A reporter on the dock managed to interview ‘A. McClellan’, the man who had discovered Hauser’s plight. ‘McClellan’, a soft-spoken Australian, well groomed with a neat black moustache, told the reporter that ‘Barton Harvey’ must have fallen asleep without covering himself and that the combination of a cold draft, recent Turkish bath and alcohol would have been enough to kill any man. The reporter queried the Australian about the rumours of large gambling stakes during the voyage, and ‘McClellan’ laughed and said he had won more money on a single horse race or a single hand of cards than had changed hands during the Olympic’s entire voyage. He told the reporter, ‘A five-pound note was the biggest bet I saw made, and that was on the ship’s pool.’

The reporter happened to notice a curious fact while he was interviewing ‘A. McClellan’. The man’s baggage was sitting on the dock next to him, but the name printed on it was ‘A. McLenna’. The reporter did not know he had been questioning George McMullen (also known as ‘Australian Pete’ and ‘The Indiana Wonder’) and that McMullen was a card sharp and one of Bud Hauser’s regular travelling companions. For that reason alone, it is almost certain that McMullen did not tell the reporter everything he knew about Hauser’s final hours. (As will be seen, professional sharps could be both inventive and reticent when asked to tell the truth about their activities.)

Four or five additional sharps were on board the Olympic during this crossing, and before the ship docked one of them sent a wireless to New York informing fellow con artists of Hauser’s passing. A delegation of sharpers went down to the dock to meet the Olympic and bid farewell to their departed brother-in-arms. These men met with the sharps who made the crossing and discussed the many stories told about Hauser. It was learned that gambling profits had indeed been very small on this crossing, the potential victims having been very conservative at betting. As was common among bunco men, the sharpers showed little sympathy or concern for their late associate, and the last we hear of Bud Hauser is that his body was ‘awaiting any undertaker who may call for it’.

The death of a well-known professional gambler on board the Olympic was no doubt a great embarrassment to the White Star Line, but this awkward state of affairs was completely forgotten in light of events that were to occur only four days later. For on 10 April, the same morning that Bud Hauser died, the Olympic’s younger sister was beginning the first day of her maiden voyage – and she, like the Olympic, was carrying a full complement of sporting men.

1

THE GAMBLING TECHNIQUES

The advent of regular passenger services across the North Atlantic was a godsend to both European and American confidence men. After booking passage on one of the ocean greyhounds, a professional gambler could leisurely browse through the first-class passenger list in search of suitable quarry. After finding a potential victim, the gambler might engage his target in casual conversation, always taking care to ask about the man’s family. This was not only disarming, but it also helped the gambler to judge his victim’s standard of living and approximate worth. A crossing of five or six days would give the sharp ample time to cultivate the good will of his intended victim, which was usually not too difficult. People always seemed to be less suspicious of strangers on board a ship than anywhere else, and it was this trusting, naïve attitude that brought more than one ocean traveller to the brink of financial ruin.

It did not take long for the shipping lines to realise that professional gamblers were present on their ships. Many lines tried to make their passengers aware of the problem by printing cautionary statements in their passenger lists as well as on signs posted in the smoking rooms. Many passengers enjoyed their card games too much to be deterred by these warnings, though, and many of these people eventually fell into the waiting hands of a sharper.

‘It has always puzzled me why passengers, who are usually men of a certain amount of common sense, allow themselves to be fleeced by the professional gamblers who frequently cross in the large passenger steamers,’ Captain Bertram Hayes once wrote in regard to the gamblers who booked passage on his own White Star vessels. He continued:

Most of these gentlemen carry the trademarks of their profession written all over their faces, and one would think that alone would prevent others from associating with them in any way, let alone from playing games of chance with them. There are exceptions, and I remember one man being pointed out to me who had the manners of the proverbial meek and mild curate, and dressed himself in a kind of a clerical costume to assist him in his business. For the first few days he played with the children on deck and so ingratiated himself with the parents, and I heard that he made a very good haul during the last day or so of the passage … Most of them are well-known to the office staff, and also to the ship’s people, and I should think it must be a little disconcerting to them to be greeted by the Second Steward when making application for their seats at table with the remark, ‘What name this time, sir?’ as very often happens. The police on either side of the Atlantic, too, inform us when they know that any of them are crossing.

Hayes went on to explain:

We cannot refuse to carry them, as steamship companies are what is known as ‘common carriers’, and by law are compelled to sell a ticket to anyone who has the money to pay for it and whose papers are in order, providing there is accommodation available in the ship … Short of actually pointing them out to each individual, every effort is made on the ship to protect their fellow passengers from them. Notices are printed in the passenger lists which everyone gets, and, in addition, notices are posted in the public rooms warning people not to play cards with people whom they don’t know, as professional gamblers are known to be on board. Yet they somehow manage to ingratiate themselves, and I have had many complaints from passengers who have been fleeced. They seldom, if ever, play for high stakes in the smoke room; that is usually done in their own staterooms or in those of their victims.

Travelling first class on a great ocean liner was a mark of prestige for ‘people of quality’, and it was natural to assume that one’s fellow passengers were of the same respectable social standing as oneself. These people often welcomed the opportunity to spend much of the voyage engaged in a game of poker or bridge whist. It was a chance to relax with old friends and new acquaintances, enjoy good fellowship and conversation, and to test one’s skill at his favourite game of cards. Under circumstances like these, the thought of one player deliberately cheating the others rarely occurred to the average player until it was too late, but there was always a ready supply of card mechanics ready and willing to apply the shears to the sheep. These men were aware that, in cards, manipulation was more profitable than speculation.

There were two varieties of these boatmen – the amateur cheat and the true professional. The amateur was a man who had a legitimate means of earning a living and only cheated at cards to supplement his income. His basic reason for cheating was greed, but sometimes a man might have a psychological need to win at any cost. One might think these part-time cheats were apt to be small-time businessmen, but this was not always so. Many of those who were ultimately exposed as cheats proved to be very wealthy people, sometimes even millionaires. One of these men, when caught, explained that he was financially secure on paper, but that certain business setbacks often caused him great difficulty in securing ready cash to meet his payrolls. Cheating at cards provided him with that ready cash.

In a different league altogether was the professional gambler. Whereas the amateur cheat was motivated by greed, it has been said that the professional was actuated by love of the game itself. Winning was not his sole delight, but equal pleasure was derived from ‘making the hazard’. A man who made a successful living from card manipulation lived under the constant threat of exposure, and this fact made him prone to thrive on the danger involved. As one gambler put it, ‘I cannot understand honest men. They live desperate lives, full of boredom.’ The professional enjoyed matching his wits and skill against the untrained senses of his intended victims, and he usually succeeded in his efforts. His winnings were called ‘pretty money’ and were generally spent very freely, the gambler being both generous and careless with his bankroll. On those rare occasions when fate went against his best efforts, the professional sharp was normally philosophical about his losses. Strangely enough, it was usually the amateur cheat who was the hardest loser, since the professional took both prosperity and adversity in his stride and recognised that an occasional loss was inevitable.

Captain Bertram Hayes once wrote:

Personally, I have no sympathy with anyone who loses money to them, and when they come to me for advice as to the best means of getting it back, I always say the same thing: ‘If you had taken my advice, or rather the company’s, you would not have lost your money. The only thing to do, if you consider you have been swindled and have paid by check, is to stop the check by wireless and stand the consequences.’ Sometimes out of curiosity I ask them: ‘Would you have taken his money providing you had been allowed to win?’ And they always answer: ‘Yes.’ They acknowledge, too, that they have read the notices warning them against playing with strangers, and sometimes add in mitigation of their foolishness: ‘But I had a few drinks before the smoke room closed, and they followed me down to my room, and it was there I lost my money.’

‘Doc’ Owen.

Captain Hayes recalled how a well-known professional once attempted to gain the good will and trust of his fellow passengers on board a certain White Star vessel under Hayes’s command:

The proudest man that I think I have ever carried was a well-known gambler, ‘Doc’ Owen by name … It was some years ago that he embarked at Liverpool on the old Majestic carrying a large silver loving cup under his arm, which he said had been presented to him by his fellow passengers on the Celtic, by which ship he had crossed to England, as a token of their regard for him. The inscription on the cup bore out his statement, and he never seemed to tire of showing it to everybody while he was with us, crew as well as passengers.

John Neville Maskelyne, the noted nineteenth-century stage conjuror and card expert, wrote that the American card sharper was better able to make a successful living than his English counterpart. Many of the older methods of cheating were tolerably well known to American gamblers but were practically unknown in England. According to Maskelyne, the average English sharp was ‘in a condition of unsophisticated innocence’ compared to a professional gambler from the United States. Yankee ingenuity apparently came to the fore whenever newer and better methods of card manipulation were found to be necessary.