Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

EDWARD J. SMITH was the celebrated captain who went down with his ship. THOMAS ANDREWS was the great and selfless hero who died saving women and children. BRUCE ISMAY was the selfish coward who caused the ship to sink. When disaster struck on the night of 14 April 1912, the lives of everyone aboard the Titanic were changed forever. Lives were lost, heroes were made – and villains were cast. The Triumvirate is a minute-by-minute investigation into the three men at the heart of the tragedy and their actions on that fateful night, using the words of survivors themselves. After over a century of half-truths and tabloid lies, it is time to ask the question: are their reputations deserved?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

By the same author

Titanic: Psychic Forewarnings of a Tragedy (Patrick Stephens, 1988)

Lost at Sea: Ghost Ships and Other Mysteries, with Michael Goss (Prometheus Books, 1994)

Titanic: Safety, Speed and Sacrifice (Transportation Trails, 1997)

‘Archie’: The Life of Major Archibald Butt from Georgia to the Titanic (Lulu.com Press, 2010)

A Death on the Titanic: The Loss of Major Archibald Butt (Lulu.com Press, 2011)

On Board RMS Titanic: Memories of the Maiden Voyage (The History Press, 2012)

Voices from the Carpathia (The History Press, 2015)

Titanic Memoirs (three volumes; Lulu.com Press, 2015)

The Titanic Files: A Paranormal Sourcebook (Lulu.com Press, 2015)

Titanic: The Return Voyage (Lulu.com Press, 2020)

‘Those Brave Fellows’: The Last Hours of the Titanic’s Band (Lulu.com Press, 2020)

The Titanic Disaster: A Medical Dossier (Lulu.com Press, 2021)

‘There’s Talk of an Iceberg’: A Titanic Investigation (Lulu.com Press, 2021)

Letters from the Titanic (The History Press, 2023)

Fate Deals a Hand: The Titanic’s Professional Gamblers (The History Press, 2023)

Titanic Collections, Volume 1: Fragments of History – The Ship (The History Press, 2023)

Titanic: Her Books and Bibliophiles (Lulu.com Press, 2024)

Titanic Collections, Volume 2: Fragments of History – The People (The History Press, coming 2024)

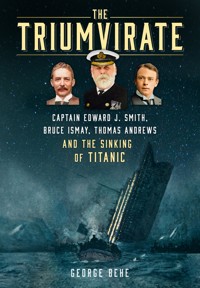

Cover illustrations: J. Bruce Ismay, Captain Edward J. Smith, Thomas Andrews (Author collection); Titanic sinking (Titanic, Filson Young, London: 1912)

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© George Behe, 2024

The right of George Behe to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 336 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Prelude to the Maiden Voyage

2 10–14 April

3 11.40 p.m.–12 a.m., 15 April

4 12–12.20 a.m.

5 12.20–12.40 a.m.

6 12.40–1 a.m.

The Eyewitnesses

7 1–1.30 a.m.

8 1.30–2 a.m.

9 2–2.20 a.m.

10 Public Perception of Captain Smith

11 Public Perception of Thomas Andrews

12 Public Perception of J. Bruce Ismay

Appendix 1: Hearsay Accounts of Captain Smith and the Child

Appendix 2: Rumour of Disagreement Between Smith and Ismay

Appendix 3: What if Smith and Andrews Had Survived?

Bibliography

Notes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I’m very grateful to my friends Don Lynch, Dr Paul Lee, Michael Poirier, Kalman Tanito, Randy Bigham, Tad Fitch, John Lamoreau, Daniel Parkes, Gerhard Schmidt-Grillmeier, John Maxtone-Graham, Olivier Mendez, Malte Fiebing-Petersen, Jack Kinzer, Peter Engberg, Lars-Inge Glad, Gavin Bell and the late Phil Gowan for contributing a number of the survivor accounts and photographs that appear in this book.

INTRODUCTION

This book started out with a simple premise – i.e., to thoroughly document the activities of the Titanic’s Captain Edward J. Smith during his vessel’s maiden voyage. However, I soon realised that Smith’s activities were intimately intertwined with those of two other ‘top players’ in the Titanic story – shipbuilder Thomas Andrews and White Star Line chairman Joseph Bruce Ismay. With that being the case, I expanded my coverage to include all three men – men whose post-disaster reputations differ from each other as greatly as night differs from day.

The fact that Captain Smith was the Titanic’s commander caused his decisions during the maiden voyage to be alternately praised or criticised by generations of Titanic researchers. By contrast, the activities of Thomas Andrews (one of the Titanic’s designers) resulted in his being universally regarded as a genuine hero, while the actions of Bruce Ismay were widely condemned by the general public and served to tarnish his reputation for the remainder of his life.

This book will document the words and actions of Smith, Andrews and Ismay throughout the entirety of the Titanic’s maiden voyage, beginning with the vessel’s departure from Southampton and continuing right through to her last few moments afloat. After describing each man’s activities during the first four days of the maiden voyage, we’ll examine the Titanic’s collision with the iceberg and will explore in detail how Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews went about determining the full extent of the damage their ship had just sustained. We’ll look at Smith’s eventual decision to evacuate his passengers from the sinking ship, and will then follow him and Andrews from place to place as they assist in alerting the Titanic’s passengers as well as loading and launching the lifeboats. Finally, we’ll show how Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews spent their final few minutes of life on board the Titanic, and will attempt to document the exact manner in which the two men met their individual fates. (It may come as a surprise for readers to learn that the so-called ‘legend’ of Captain Smith attempting to save a child is corroborated by a primary source, the existence of which few people are currently aware.)

In addition to monitoring the activities of Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews, we’ll be following the activities of Bruce Ismay throughout the Titanic’s maiden voyage and sinking in order to determine whether or not he truly deserves the unfortunate reputation that has been pinned to his coat-tails ever since the disaster.

This book won’t be telling the story of Smith, Andrews and Ismay by describing their bare-bones activities in general terms. Instead, we’ll be utilising the words of the three men themselves as well as offering accounts of their activities as observed by eyewitnesses who had personal interactions with the three men during the Titanic’s maiden voyage. In other words, we’ll be telling the stories of Captain Smith, Thomas Andrews and Bruce Ismay by utilising the voices of people who were there.

Through the years I’ve always been interested in figuring out exactly how Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews first determined that the Titanic had received her death blow while colliding with the iceberg. Hollywood always depicts an intense private conference between the two men during which Andrews explains to Smith why the ship cannot possibly remain afloat, but is this what really happened? Was Captain Smith truly ‘catatonic’ during the entire evacuation process, as one present-day author has claimed? How did Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews meet their individual fates when the Titanic went down? How did Bruce Ismay come to survive the disaster when the ship’s captain and builder both lost their lives? Were rumours of Ismay’s supposed cowardice based in fact? We’ll examine each of these questions (and others) as our story gradually unfolds.

While examining our various eyewitness accounts, one thing will quickly become apparent to the reader: different eyewitnesses to the same event or conversation often remembered things slightly differently. (Although the gist of their stories is usually the same, the exact wording or exact locations or exact times of occurrence of the events in question often are not.) For instance, did Captain Smith issue certain orders to the occupants of a specific lifeboat before that boat was lowered to the ocean’s surface, or did he use his megaphone to call out his orders after the lifeboat had already begun rowing away from the ship’s side? Although some of these questions are unanswerable due to conflicting accounts, I have done my best to illustrate each of these inconsistencies and have assigned a ‘probable’ time and location to each of our described events. Even so, and as author Walter Lord once pointed out, ‘It is a rash man indeed who would set himself up as final arbiter on all that happened the incredible night the Titanic went down’.

At any rate, I have done my best to tell the story accurately, but I invite readers to examine the eyewitness accounts and evaluate the actions of Edward J. Smith, Thomas Andrews and Bruce Ismay for themselves.

George Behe

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Joseph Bruce Ismay; Captain Edward J. Smith; Thomas Andrews. (Author’s collection)

1

PRELUDE TO THE MAIDEN VOYAGE

We’ll begin our presentation by reading the reminiscences of a number of people who were personal friends of Captain Edward J. Smith and who did their best to describe the kind of man he was …

*

‘Captain Smith loved the sea,’ remembered Mrs Ann O’Donnell, a friend of Smith’s since childhood:

From his boyhood days until he was placed in command of the greatest liners in the world, he felt a strong attachment for the sailor’s life. He was a kindly, thoughtful and genial man. He never rose above his position, and I never knew him to forget that once he was listed on the ship’s books as merely an able seaman. He never forgot his friends and loved to cherish memories of the days spent in the little town in England.

‘Capt. Smith was one of the bravest then that ever lived,’ Mrs O’Donnell went on:

He was never known to have flinched in the face of the most serious danger. The utmost confidence was always placed in him by the owners of the ships he commanded. He was thoroughly reliable and conscientious, and was loved by everyone who knew him. They could not help it, for he seemed to be a man who was a friend to all who understood him.1

Charles Lightoller was destined to serve with Captain Edward J. Smith as the Titanic’s second officer. Captain Smith, or ‘E.J.’ as he was familiarly and affectionately known, was quite a character in the shipping world, Lightoller wrote later:

Tall, full whiskered and broad. At first sight you would think to yourself, ‘Here’s a typical Western Ocean Captain. Bluff, hearty, and I’ll bet he’s got a voice like a foghorn.’ As a matter of fact, he had a pleasant quiet voice and invariable smile. A voice he rarely raised above a conversational tone – not to say he couldn’t; in fact, I have often heard him bark an order that made a man come to himself with a bump. He was a great favorite, and a man any officer would give his ears to sail under. I had been with him many years, off and on, in the mail boats, Majestic, mainly, and it was an education to see him con his own ship up through the intricate channels entering New York at full speed. One particularly bad corner, known as the South-West Spit, used to make us fairly flush with pride as he swung her round, judging his distances to a nicety; she heeling over to the helm with only a matter of feet to spare between each end of the ship and the banks.2

‘Capt. Smith was a man who had a very, very clear record,’ agreed Joseph Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line. ‘I should think very few commanders crossing the Atlantic have as good a record as Capt Smith had, until he had the unfortunate collision with the Hawke.’3

Sixth Officer James Moody had an equally high opinion and equally respectful attitude towards Captain Smith: ‘Though I believe he’s an awful stickler for discipline, he’s popular with everybody,’ Moody wrote in a letter to his sister.4

‘During most of my service I have been on ships with Captain Smith, of course, starting when he was a junior officer,’ Bathroom Steward Samuel Rule remembered. ‘A better man never walked a deck. His crew knew him to be a good, kind-hearted man, and we looked upon him as a sort of father.’5

‘Captain Smith ranked all men in the service, and he ranked them because of carefulness, prudence, skill and long and valued service,’ said the White Star Line’s Captain John N. Smith, who spoke with Smith on the same day he’d been given command of the brand-new Olympic:

He came down to the pier and clapped his hand on my shoulder. ‘Captain,’ he said, ‘they are making brave ships these days, and I am in charge of the bravest of them, but there will never be boats like the sailing ships we used to take out of Liverpool. Those were the clippers that made old England the queen of the seas.’ He said that the senior captain of the White Star fleet was a kindly, humorous, grave man, watchful from long sailing of the sudden and treacherous seas; gentle to those under him, but strict in the hour of duty.6

Captain David Evans, who had served as Captain Smith’s chief officer on the Majestic, spoke very highly of Smith and said he was the finest type of British sailor – a splendid fellow to get along with, although the strongest disciplinarian. If there was any man he would choose to sail a ship across the Atlantic, Captain Evans said Smith would be that man.7

*

Professional sailors weren’t the only people who had a favourable opinion of Captain Smith.

‘All the passengers were eager to meet Captain Smith,’ remembered Mrs L. B. Judd, who once sailed with him on the Baltic:

He was so different from the captain of the Finland, which vessel I took from New York to Antwerp on the outward trip across. The captain of the Finland was jolly and had plenty of time to converse with the passengers, but Captain Smith had little to say. He avoided talking with us although he was very courteous.

‘Every morning he would have an inspection of the crew,’ Mrs Judd went on:

He made it a practice of speaking a kindly word to each man. It seemed to me that they would do anything for him. Captain Smith was always occupied. He spent but little time in his office, being at his post continually. The passengers did not meet him at meal time as he dined alone in a private apartment. He was my ideal of a captain. He was too occupied to say more than a few words when spoken to. From his accent I gathered that he was of Scotch descent.8

*

Howard Weber, president of the Springfield, Illinois, First National Bank, chatted with his friend Captain Smith on the Olympic while returning from his last trip abroad.

‘The Titanic will soon be ready for the water,’ Smith told Mr Weber. ‘I expect to be given her charge, but somehow I rather regret to leave my present boat, the Olympic.’

‘I knew Captain Smith, not as an acquaintance, but as a good friend,’ Weber related later:

We always made it a point to be together on trips across the ocean, and he took pride in informing me of new appliances which the ships upon which he was placed had … Captain Smith was a congenial old man, and one people could not help liking. I was with him last time last year when we crossed the ocean on the Olympic. The captain at that time said he expected to be put on the new Titanic, but expressed himself as preferring just a little to stay with the Olympic … Officers of the White Star Line and Captain Smith himself believed just as sincerely as anything that the boat [Titanic] could not sink.9

George W. Chauncey, president of the Mechanics Bank, said, ‘I was a passenger on board the Olympic on her first eastward voyage, when Captain Smith was in command of her. I met the captain and found him a fine gentleman and a first-class mariner. He inspired everybody on board with confidence.’10

Mr J. E. Hodder Williams was another good friend of Captain Smith. ‘He was amazingly informed on every phase of present-day affairs,’ Mr Williams wrote:

and that was hardly to be wondered at, for scarcely a well-known man or woman who crossed the Atlantic during the last twenty years but had at some time sat at his table. He read widely, but men more than books. He was a good listener, on the whole, although he liked to get in a yarn himself now and again, but he had scant patience with bores or people who ‘gushed’. I have seen him quell both …

He had lived his whole life on the sea and … used to laugh at us for talking as if we knew anything of its terrors in these days of floating hotels. He had served his apprenticeship in a rough school, and knew the sea and ships in their uncounted moods. He had an infinite respect – I think that is the right word – for the sea.

Absolutely fearless, he had no illusions as to man’s power in the face of the infinite. He would never prophesy an hour ahead. If you asked him about times of arrival, it was always ‘if all goes well’. I am sure now that he must have had many terrible secrets of narrowly averted tragedies locked away behind those sailor eyes of his.11

Mr Hodder Williams continued with a few more reminiscences about his old friend:

Late in the evening the captain’s boy would come with an invitation to his [Smith’s] room on the bridge, and I learned something of the things hidden away behind an exterior that some thought stern and grim. Those keen eyes of his had pierced far into the ugly side of life as it flaunts itself on the monster liner, but they had never lost their power of pity.

I saw him angry once, and that was when a passenger made a slighting remark about one of the captain’s old officers having gone wrong. ‘How do you know that’s true?’ he asked, sharply. ‘If you want to, you can always hear enough stories about every officer to ruin his reputation.’ And later on I found that Captain Smith knew that the story was all too true, and that he had given up one of his few, so highly prized days between trips to journey to this man’s home and try to arrange for him to have a fresh start.

I could tell, too, of the time when he promised to sit by the operating table when a serious operation was to be performed on an old comrade, who felt that he could go through with it only if the captain were there all the time, and how he kept that promise to the letter.12

W. W. Sanford of New York City agreed:

He was the kind of man who is at his best in a crisis … I recall the last time I saw him we talked, principally of politics, in his cabin on the Olympic. He was a keen follower of the politics of this country and England, and his ideas were always worth listening to. He was a strong advocate of clean politics.

I cannot imagine Captain Smith taking chances … His company might do so, but Captain Smith never. He was a shrewd, careful commander.13

‘There never was a braver or better officer than Captain Smith,’ said Irish businessman J. E. Graham, who made five crossings with Smith. ‘Although bravest of the brave, he was at all times cautious.’14

‘I have never known Captain Smith to take an unnecessary risk,’ wrote Joseph Francis Taylor:

He was always cool and thoughtful, attending to every detail of navigation and never flinching when he had to undergo hardships in his line of duty. Whenever we were off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland … he had the ship creep along slowly and he used every device known to ward off danger. The toot of a horn on another ship would cause him to stop his own craft dead and take locations before going on.

I believe that Captain Smith would allow no suggestion [from another person] to cause him to run into danger. In his long and honorable career at sea he met with but one mishap … the result of circumstances over which he had no control. The former accident I refer to is when the Olympic had trouble because of the suction created when she left port. For the benefit of those who have been misled by pictures supposed to be of Captain Smith, I will say this: He was 5 feet 11 inches in height, weighed about 200 pounds, wore a short gray Van Dyke beard and a mustache, and was the picture of vigor and alertness.

He resembled none of the Santa Claus style of pictures I have observed in a certain paper … He was a man who seemed to live on the bridge of his ship through life.15

Captain Anning, former captain of the White Star liner Persic, said that Captain Smith was ‘a man absolutely devoid of nervousness. He was one of the smartest navigators on the Atlantic. He had had a splendid career, serving at different periods in the Pacific trade between San Francisco, Japan and China before being transferred to the Atlantic.’16

‘Capt. E. J. Smith, commodore of the White Star fleet, believed he had been hoodooed,’ said retired English businessman J. P. Grant, ‘and several months ago told me that if he would have another accident with a liner of which he had the command he would resign his ship and retire into private life.’

‘Captain Smith was recognized as one of the ablest sea captains of the Atlantic, and White Star officials had the utmost confidence in him,’ Mr Grant went on:

Within the last three years, however, he seemed to be unfortunate in his commands. He was in the Olympic when this ship met with three accidents in one year. It was first struck by the British man-of-war Hawke, and the White Star line had to spend $500,000 to repair it. It then lost a blade of a screw by running into a submarine wreck and had to put into Belfast for repairs. When the ship left the Belfast harbor it ran aground.

It shows what great confidence his superiors had in him, because he retained his command of the Olympic until he was transferred to command the Titanic on its maiden voyage. In all these mishaps it was always found that Captain Smith was not to blame, but he came to fear his luck and often spoke about it to me.17

*

Captain Smith was a versatile man who had other talents besides seamanship. His friends Mr and Mrs Henry Buckhall were members of Long Island’s Nassau Country Club, and it was there they discovered that the good captain played a very respectable game of golf.18 Mr Buckhall said:

Captain Smith had nothing of the old salt in appearance … He was over six feet in height, well proportioned, fair complexion, and had the appearance of a military or naval officer. His manner was quiet and his address pleasing. It was not necessary for him to be severe in his tone on shipboard to command respect. His whole appearance did that, and as a prominent lady remarked, when introduced to him, ‘His countenance inspired confidence.’ He was very little in evidence on shipboard, being only where his duty called him. The large circle of friends among ocean travelers that he had was not created by his catering to their society.

He concluded:

Last fall, on Captain Smith’s return to New York after the collision with the Hawke, about one hundred of his friends gave him a dinner at the Metropolitan Club as an expression of their sympathy and confidence in him … Captain Smith made a very modest speech thanking his friends for their esteem. Besides good wishes, a purse of several thousand dollars was presented to him.19

*

But good seamanship, political savvy and good ‘golfmanship’ were insufficient to protect Captain Smith from every eventuality, as a 1909 American newspaper article made clear:

Captain Smith of the Adriatic … and the ship’s surgeon, Dr [William] O’Loughlin were invited to Marblehead to spend a few days. As they started ashore yesterday, they went to the customs office on the pier and offered the valises they carried for inspection.

Each officer was carrying a box of cigars, upon which the seals had been broken. In spite of their protests, these cigars were confiscated. In the doctor’s valise was a bottle of whisky. This suffered the same fate.20

‘Having fitted out this magnificent vessel, the Titanic, we proceeded to man her with all that was best in the White Star organization,’ White Star Line chairman Bruce Ismay said later:

and that, I believe, without boasting, means everything in the way of skill, manhood and esprit de corps. Whenever a man had distinguished himself in the service by means of ability and devotion to duty, he was earmarked at once to go to the Olympic or Titanic, if it were possible to spare him from his existing position, with the result that, from Captain Smith, Chief Engineer Bell, Dr O’Loughlin, Chief Purser McElroy, Chief Steward Latimer, downwards, I can say without fear of contradiction, that a finer set of men never manned a ship, nor could be found in the whole of the Mercantile Marine of the country, and no higher testimony than this can be paid to the worth of any crew.21

*

Captain Smith and Dr William O’Loughlin were good friends and had an excellent working relationship, and one day Dr O’Loughlin told his colleague, Dr J. C. H. Beaumont, how he came to be transferred from the Olympic to the Titanic. Beaumont later wrote:

Dr O’Loughlin, ‘Old Billy’ as we called him, had been for many years in the service, and I followed him up to the Olympic. Whether he had any premonition about the Titanic … I cannot say. But I do know that during a talk with him in the South Western Hotel he did tell me that he was tired at this time of life to be changing from one ship to another. When he mentioned this to Captain Smith the latter chided him for being lazy and told him to pack up and come with him. So fate decreed that ‘Billy’ should go on the Titanic and I to the Olympic.22

Just before the Titanic was delivered from Belfast to Southampton to prepare for her maiden voyage, Harland & Wolff’s managing director John Kempster asked Captain Smith if the traditional old-time seaman’s courageous fearlessness in the face of death still existed. Smith replied with emphasis, ‘If a disaster like that to the Birkenhead happened, they would go down as those men went down.’23

*

On 2 April the Titanic, under the command of Captain Edward J. Smith, completed her sea trials in Belfast.

*

On 3 April the Titanic, under the command of Captain Smith, was midway on her delivery voyage from Belfast to Southampton.

*

On 4 April, at 1.15 a.m., the Titanic docked after completing her delivery trip from Belfast to Southampton, where preparations would continue for the vessel’s 10 April maiden voyage. Later that day, crewmen began signing onto the vessel in preparation for the voyage.

On 6 April 1912 Benjamin Steele, the Marine Superintendent at Southampton Docks, sent Captain Smith a message describing a possible danger to his future navigation of the Titanic:

Please note the following reports: Rotterdam, March 27 Rotterdam (3) from New York reports March 20 in lat. 40.24 N., long. 64.41 W. passed a piece of mast standing perpendicular, height about 10 feet, apparently belonging to submerged wreckage.24

*

On 8 April 1912 a lifeboat drill was held on the Titanic at Southampton, and the crew lined up in two rows on the boat deck while volunteers were called for. Someone in the second row pushed Fireman George Beauchamp from behind and, when he stumbled forward, he was thought to be a volunteer and was picked to man one of the boats during the drill.25

*

A standard form letter advocating safe and prudent navigation practices was issued by the White Star Line to each of its captains:

Captain [Edward J. Smith]

Liverpool

Dear Sir,

In placing the steamer [Titanic] temporarily under your command, we desire to direct your attention to the company’s regulations for the safe and efficient navigation of its vessels and also to impress upon you in the most forcible manner, the paramount and vital importance of exercising the utmost caution in the navigation of the ships and that the safety of the passengers and crew weighs with us above and before all other considerations.

You are to dismiss all idea of competitive passages with other vessels, and to concentrate your attention upon a cautious, prudent and ever watchful system of navigation which shall lose time or suffer any other temporary inconvenience rather than incur the slightest risk which can be avoided.

We request you to make an invariable practice of being yourself on deck and in full charge when the weather is thick or obscure, in all narrow waters and whenever the ship is within sixty miles of land, also that you will give a wide berth to all Headlands, Shoals and other positions involving peril, that where possible you will take cross bearings when approaching any coast, and that you will keep the lead going when approaching the land in thick or doubtful weather, as the only really reliable proof of the safety of the ship’s position.

The most rigid discipline on the part of your officers must be observed and you will require them to avoid at all times convivial intercourse with passengers or each other, the crew also must be kept under judicious control and the lookout men carefully selected and zealously watched when on duty, and you are to report to us promptly all instances of inattention, incapacity or irregularity on the part of your officers or any others under your control.

Whilst we have confidence in your sobriety of habit and demeanor, we exhort you to use your best endeavors to imbue your officers and all those about you with a due sense of the advantage which will accrue not only to the Company but to themselves by being strictly temperate, as this quality will weigh with us in an especial degree when giving promotion. The consumption of coals, water, provisions and other stores, together with the prevention of waste in any of the departments, should engage your daily and most careful attention, in order that you may be forewarned of any deficiency that may be impending, that waste may be avoided, and a limitation in quantity determined on, in case you should deem such a step necessary, in the interest of prudence.

Should you at any time have any suggestion to make bearing upon the improvement of the steamers, their arrangement, equipment or any other matter connected with the service on which they are engaged, we shall always be glad to receive and consider same.

In the event of a collision, stranding or other accident of a serious nature happening to one of the Company’s steamers, necessitating the holding of an Enquiry by the Managers, written notice of the same will be given to the Commander, who shall immediately on receipt of such notice hand in a letter tendering the resignation of his position in the Company’s Services, which letter will be retained pending the result of the Enquiry.

We have alluded, generally, to the subject of safe and watchful navigation, and we desire earnestly to impress on you how deeply these considerations affect not only the well-being, but the very existence of this Company itself, and the injury which it would sustain in the event of any misfortune attending the management of your vessel, first from the blow which would be inflicted to the reputation of the Line, secondly from the pecuniary loss that would accrue, (the Company being their own insurers), and thirdly from the interruption of a regular service upon which the success of the present organization must necessarily depend.

We request your cooperation in achieving those satisfactory results which can only be obtained by unremitting care and prudence at all times, whether in the presence of danger or when by its absence you may be lured into a false sense of security; where there is least apparent peril the greatest danger often exists, a well-founded truism which cannot be too prominently borne in mind.

We are,

Yours truly

[White Star Line]26

*

A newspaper interview with Glenn Marston (a friend of Captain Smith’s) described his interactions with Smith during an earlier voyage of the White Star liner Olympic:

Chicago, April 18 – That Captain Edward J. Smith of the Titanic knew that the steamer was not properly equipped with lifeboats and other life-saving devices, and that he protested against the lack of precaution, but without success, to the officials of the line, is the statement of Glenn Marston, a friend of the captain who is stopping in Chicago at the Brevoort Hotel.

Mr Marston is connected with the Public Service magazine and just returned from Europe, where he made an investigation of the government-owned utilities.

He has been a friend of Captain Smith for a number of years and on his trip abroad both crossed and returned on the Olympic, a companion ship of the Titanic, although slightly smaller in tonnage, which was commanded by Captain Smith.

According to Mr Marston, Captain Smith had always insisted that the steamers that he commanded should carry an equipment of boats and rafts sufficient to take care of every passenger and every member of the crew in case of disaster at sea.

He had been successful in his demands until he took command of the Olympic, when he was unable to induce the officials of the line to carry more boats than were included in the original plans of the ship.

He was also unable to induce the company officials to equip the Titanic with additional lifeboats when he took command of that ship.

‘Captain Smith knew that the Titanic did not carry enough lifeboats and rafts,’ said Mr Marston last night. ‘When he went to Belfast, where the Titanic was built, just after he was notified that he was to take command he noticed the small number of life-saving devices and was not satisfied, he told me. I got into a discussion with him when I was returning on the Olympic, on what I believe was his last trip on that ship before he took command of the Titanic.

‘I noticed the small number of boats and rafts aboard for the heavy passenger-carrying capacity of the ship and remarked on it to Capt Smith,’ said Mr Marston.

‘Yes,’ he replied, ‘If the ship should strike a submerged derelict or iceberg that would cut through into several of the watertight compartments, we have not enough boats or rafts aboard to take care of more than one-third of the passengers.

‘The Titanic, too, is no better equipped. It ought to carry at least double the number of boats and rafts that it does to afford any real protection to the passengers. Besides there always is danger of some of the boats becoming damaged or swept sway before they can be manned.’27

Mr Marston asked Captain Smith why the company took such a chance, and whether it was to save money:

‘No,’ the captain is quoted as replying. ‘I don’t think it’s from motives of economy, as the additional equipment would cost only a trifle when compared to the cost of the ship, but the builders nowadays believe that their boats are practically indestructible as far as sinking goes, because of the watertight bulkheads, and that the only need of lifeboats at all is for purposes of rescue from other ships that are not so modernly constructed, or to land passengers in case of the ship going ashore. They hardly regard them as life-saving equipment.

‘Personally, I believe that a ship ought to carry enough boats and rafts to carry every soul aboard it. I have followed the sea now for forty years, and have attributed my success in not having an accident, until we were rammed by the Hawke in the Solent at Southampton, and I was exonerated in that case, to never taking a chance.

‘I always take the safe course. While there is only one chance in a thousand that a ship like the Olympic or Titanic may meet with an accident that would injure it so severely that it would sink before aid would arrive, yet if I had my way, both ships would be equipped with twice the number of lifeboats and rafts. In the old days it was different from today. With the mergers and Trusts in the steamship business, now the captain has little to say regarding equipment. All of that has been taken out of his hands and is taken care of at the main office.’28

In another interview, he said:

‘In the cases of ocean steamers,’ Captain Smith continued, ‘there is not one of the transatlantic liners that could not carry enough boats and rafts to carry every passenger aboard. Of course, such equipment would take up space, but it would make but little difference in the vessel’s tonnage.’29

‘What wind or weather would you fear, supposing your ship were in danger?’ a friend of Captain Smith’s asked him at dinner on the night before the Titanic sailed.

‘I fear no winds or weather,’ Smith replied. ‘I fear only icebergs.’30

*

‘Remember, upon the conduct of each depends the fate of all.’

– Alexander the Great.

‘Everybody, soon or late, sits down to a banquet of consequences.’

– Robert Louis Stevenson.

2

10–14 APRIL

10 April 1912

At about 7.30 a.m. on the morning of 10 April 1912, Captain Edward J. Smith, wearing a bowler hat and long overcoat, boarded the new White Star liner Titanic in Southampton, England.1 Captain Smith went directly to his cabin to receive the sailing report from Chief Officer Henry Wilde, and at 8 a.m. the Blue Ensign was hoisted at the ship’s stern while the crew began to assemble on deck for muster. The ship’s articles – the ‘sign-on list’ – for each department was distributed to the respective department heads.

On this morning Captain Smith was kept busy meeting and assisting the various officials whose approval was required before the vessel could put to sea. Captain Benjamin Steele, the White Star Line’s Marine Superintendent, supervised the muster as each man was scrutinised by one of the ship’s doctors. Another company representative examined each department’s final rosters and handed them to Captain Steele, who took them to Captain Smith for his examination and approval.

While the Titanic’s passengers were in the process of boarding the great vessel, the local Board of Trade inspector, Captain Maurice Clarke, was making his final check of the ship. Despite a rigorous inspection that even required the lowering of two of the ship’s lifeboats, Clarke’s final report never mentioned the existence of a fire that was currently burning in one of the ship’s coal bunkers. Even so, Captain Smith was probably assured by Chief Engineer Joseph Bell that the situation was under control, and that any potential damage would be confined to a small portion of the transverse bulkhead without endangering the soundness of the hull.

While signing the final documents, Captain Steele received the formal Captain’s Report from Smith, stating: ‘I hereby report this ship loaded and ready for sea. The engines and boilers are in good order for the voyage, and all charts and sailing directions up-to-date. Your obedient servant, Edward J. Smith.’ There were handshakes all around, after which the two officials left the bridge.2

At one point during the morning hours, young Roy Diaper accompanied his father on board the Titanic to have a few words with Captain Smith before the vessel left Southampton on her maiden voyage. Diaper remembered:

My … impression I got then was of a tall man completely bearded and he was wearing a frock coat; he had on a peaked cap … it had a small brim and small top. I remember my father speaking to him. Captain Smith didn’t speak to me, but he bent down and shook me by the hand. There was a tremendous bustle going on, and Captain Smith was surrounded by people.3

Marine artist Norman Wilkinson was paying his own visit to the Southampton docks on the morning of 10 April. He wrote later:

On reaching the jetty at the top of Southampton Water I saw the new White Star liner Titanic. She was to sail on her maiden voyage that afternoon. I said to my friend, ‘What a bit of luck. I know the captain. We will go aboard and look around the ship.’

The quartermaster at the head of the gangway said that Captain Smith was on board and took us along to his cabin. He was nearly 60 years old with 40 years’ service in the Line and radiated Edwardian confidence. He gave me a warm welcome but said that he was extremely busy and would hand us over to the Purser, who would show us round. We made a thorough tour of the splendid ship. Over the mantelpiece in the smoking-room was a painting I had done as a commission for Lord Pirrie of Harland & Wolff of Belfast, who had built her. The subject of the picture was Plymouth Harbour.4

Captain Smith’s wife Eleanor and their daughter Helen also paid a brief visit to the Titanic that morning and visited the bridge before going ashore again. The family of Bruce Ismay, president and managing director of the White Star Line, toured the ship as well before bidding farewell to him and returning ashore.5

At around 10.30 a.m. representatives of the press were escorted to the Titanic’s boat deck, where they encountered Captain Smith standing near the bridge. Two press photographers snapped pictures of Smith on the port boat deck standing alongside the quarters of First Officer William Murdoch and Second Officer Charles Lightoller, and one photographer snapped two additional photos of the Titanic’s captain as he stood outside the vessel’s navigating bridge.6

Fifth Officer Harold Lowe was also participating in the ship’s pre-voyage activities and preparations. ‘The general boat list passed through my hands in being sent to the captain for approval,’ he recalled. ‘I glanced at this list casually, and remember from this glance that there were three seamen assigned to some of the boats and four to others.’7

As the Titanic’s noon sailing time approached, the various officials took their leave of the ship and all gangways except one were pulled ashore. Thomas Andrews, the managing director of Harland & Wolff, remained on board the Titanic in order to monitor the ship’s performance during the maiden voyage and make any necessary repairs that might be required before the vessel reached New York. Presently Andrews accompanied Bruce Ismay onto the bridge, where both men exchanged brief greetings with Captain Smith and Chief Officer Henry Wilde. Pilot George Bowyer also conferred with the Titanic’s master about the draughts, turning circles and manoeuvrability of the great liner.

At twelve noon Captain Smith gave the order to sound the Titanic’s whistles and cast off her mooring lines. Five tugs eased the great vessel out into the turning circle and, before casting off, they manoeuvred her bows into a position facing down the River Test. The engine telegraph rang down to the engine room for the ship’s screws to be engaged, and as the two huge bronze wing propellers began turning slowly, the Titanic eased ahead and gradually began to pick up speed.

While the Titanic was in the process of leaving Southampton harbour, she nearly suffered a collision with the liner New York when the latter vessel broke her mooring lines and was pulled away from the dock and into the channel towards the passing White Star liner. Quick work by attending tugs averted the collision, and after the danger was past a group of first-class passengers are reported to have discussed the incident with Captain Smith.

‘They tell me,’ said one of the group, ‘that the ship is absolutely unsinkable.’

‘Yes,’ replied Captain Smith:

that is correct. The whole ship is built of watertight compartments. Should one be smashed, it would fill with water, but this wouldn’t affect the rest of the ship. The crowd on board this ship is as safe as if it were on land – safer, for that matter, since on land, especially in your New York, one is apt to be run down with one of those automobiles. I never feel as safe on land as I do on water. You have to deal only with nature on water, and nature is usually kindly and regular in her habits. If you study your charts, you know pretty well just what she is going to do.8

*

That afternoon first-class passenger Robert Daniel was on deck with some friends and was taking special note of several well-known people nearby. Daniel ‘pointed out some prominent people’ whose number included Captain Smith, artist Frank Millet and others.9

As for Thomas Andrews, his subsequent days on board the Titanic were soon to settle into a regular routine and began at 7 a.m. when Steward Henry Etches knocked at his cabin door (A-36, at the aft end of A deck) carrying some fruit and a cup of tea. Etches knew this light breakfast would be the beginning of a busy day for Andrews, during which he would continue to add to an unending series of notes of ‘any improvements that could be made’ to the brand-new White Star liner. In looking around the cabin, Etches could see that Andrews ‘had charts rolled up by the side of his bed, and he had papers of all descriptions on his table during the day,’ and the steward knew that Andrews would spend his entire day ‘working all the time’ until evening arrived. ‘He had a separate cabin, with bathroom attached – the only cabin,’ Etches recalled.10

Bruce Ismay likewise knew that Thomas Andrews would be kept busy throughout the Titanic’s entire maiden voyage.

‘He was about the ship all the time, I believe,’ Ismay recalled later:

Naturally, in a ship of that size, there were a great many minor defects on board the ship, which he was rectifying. I think there were probably three or four apprentices on board from Messrs. Harland & Wolff’s shipbuilding yard, who were there to right any small detail which was wrong … A door might jam, or a pipe might burst, or anything like that, and they were there to make it good at once.11

Even so, Thomas Andrews and Bruce Ismay never had any detailed discussions about the Titanic while the vessel was at sea. ‘The only plan which Mr Andrews submitted to me,’ Ismay testified later, ‘was a plan where he said he thought the writing room and reading room was unnecessarily large, and he said he saw a way of putting a stateroom in the forward end of it. That was a matter which would have been taken up and thoroughly discussed after we got back to England.’12

First-class passenger Antoinette Flegenheim was well aware of the fact that Captain Smith, Bruce Ismay and Thomas Andrews were all on board the Titanic during the maiden voyage. ‘Not only was the best commander of the fleet at the helm,’ she said later:

but the chairman of the line was there, as well as the chief draughtsman of the company that had built this fine ship. And to the latter many went to express their congratulations for having designed such a wonder. Some others, myself included, went to him with less excitement, to suggest adjustments, tweakings. Things that required his attention, really, for as much as Titanic closed perfection, it never actually fully reached it. Complaints were not scarce.13

But Thomas Andrews didn’t wait for complaints and suggestions to be brought to him – he actively sought them out, as Stewardess Violet Jessop remembered:

Perhaps we felt proprietary about this last ship because, in our small way, we were responsible for many changes and improvements … There were things of seemingly small importance to the disinterested but of tremendous help to us, improvements that would make our life aboard less arduous and make her more of a home than we had hitherto known at sea.

It was quite unusual for members of the catering department to be consulted about changes that would benefit their comforts or ease their toil, So when the designer paid us this thoughtful compliment, we realized it was a great privilege; our esteem for him, already high, knew no bounds.14

Indeed, Titanic’s victualling staff was so grateful for Thomas Andrews’ show of concern for their welfare that they decided to do something about it. Jessop continued:

Rather diffidently, they asked this always approachable man to honour them by a visit to the glory hole, which he did to receive their warm-hearted thanks … His gentle face lit up with real pleasure, for he alone understood – nobody else had bothered to understand – how deeply these men must feel to show any sentiment at all; he knew only too well their usual uncouth acceptance of most things, good or bad.15

‘I was proud of him,’ Stewardess Mary Sloan said of Thomas Andrews:

He came from home and he made you feel on the ship that all was right. It was good to hear his laugh and have him near you. If anything went wrong it was always to Mr Andrews one went. Even when a fan stuck in a stateroom, one would say, ‘Wait for Mr Andrews, he’ll soon see to it,’ and you would find him settling even the little quarrels that arose between ourselves. Nothing came amiss to him, nothing at all. And he was always the same, a nod and a smile or a hearty word whenever he saw you and no matter what he was at.16

During his typical workdays on board the Titanic, Thomas Andrews wore a set of blue coveralls whenever he went down into the engineering department, with a second set of coveralls being reserved for his trips to the boiler rooms; one or the other of these two sets of coveralls could often be seen thrown onto Andrews’ bed whenever they were not in use. During his own workday, Steward Etches knew he might meet Mr Andrews ‘in all parts [of the ship], with workmen, going about. I mentioned several things to him, and he was with workmen having them attended to. The whole of the day he was working from one part of the ship to the other.’17

Meanwhile, down in the Titanic’s boiler rooms, the stokers sliced and scraped as they shovelled coal into the ship’s hungry furnaces. ‘My recollection is that between Southampton and Cherbourg we ran at 60 revolutions,’ Bruce Ismay recalled later.18

Despite the fact that the coal fire burning in one of the Titanic’s bunkers was being kept a secret, word of its existence was gradually leaking out and making its way to the passenger decks. ‘The first day at sea passengers heard reports that the Titanic was afire,’ Mrs Thomas Brown reported later. ‘The officers denied it, but I was told on good authority that there was a fire in one of the coal bunkers and a special crew of men were kept at work day and night to keep it under control. I believe this to be true.’19

After the Titanic touched at Cherbourg, France, on the evening of 10 April, Thomas Andrews penned another quick letter to his wife. ‘We reached here in nice time and took on board quite a number of passengers,’ he wrote. ‘The two little tenders looked well, you will remember we built them about a year ago. We expect to arrive at Queenstown about 10.30 a.m. tomorrow. The weather is fine and everything shaping for a good voyage. I have a seat at the Doctor’s table.’20

That evening Mrs Elisabeth Lines was in the Titanic’s first-class dining room when she noticed a nearby man reposing in the ‘seat of honor’ that she supposed was reserved for the ship’s captain. ‘He sat at the head table, and I supposed he was Captain Smith,’ Mrs Lines testified later. ‘I asked my table steward in the dining room if that were not the captain and he said yes, the first evening that we were out.’21

This was not the last time that Mrs Lines would see Captain Edward J. Smith during the Titanic’s maiden voyage …

11 April 1912

After departing Cherbourg on the evening of 10 April, Titanic steamed through the night towards Ireland, and on the morning of 11 April Thomas Andrews wrote another letter to his wife that was later posted at Queenstown. He reported that everything on board the ship was going splendidly and that he was pleased to have received so much kindness from everyone on board.22

That morning a general inspection of the Titanic’s watertight doors took place, and a drill was conducted in order to make sure they were all operating properly. ‘I saw them closed at bulkhead door inspection on the day after we left Southampton,’ Steward John Hart testified later. ‘The Chief Officer came round with Mr Andrews, the man representing Harland & Wolff’s.’ It was Hart’s duty to close one of the watertight doors on E deck, and it was his understanding that these manual tests were conducted ‘in case anything should go wrong with the machinery leading from the bridge in closing those doors’.23

It was Bruce Ismay’s understanding that the Titanic’s engines were making seventy revolutions during her crossing to Ireland,24