Female Lines E-Book

5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

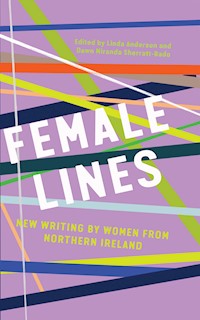

In 1985, The Female Line: Northern Irish Women Writers was published. A pioneering anthology at the time, it gave many Northern Irish women writers their first opportunity for publication. Now, over thirty years later, Female Lines: New Writing by Women from Northern Ireland – a stunning mosaic of work by some of the best contemporary women writers from Northern Ireland – acts as both a new staging post and a sequel to its vibrant feminist predecessor. Trans-genre in contents and including both experienced and newer women writers, this landmark anthology features women writers playing with different modes, forms, and innovations – from magical realism and surrealism to humour and multi-perspective narratives – and celebrates fiction, poetry, drama, essays, life writing, and photography. It considers how much has changed or stayed the same in terms of scope and opportunity for women writers and for women more generally in Northern Irish society (and its diaspora) in the post-Good Friday Agreement era. Northern Irish women's writing is going from strength to strength and this anthology captures its current richness and audacity. Featuring work by: Linda Anderson, Jean Bleakney, Maureen Boyle, Colette Bryce, Lucy Caldwell, Emma Campbell, Julieann Campbell, Ruth Carr, Jan Carson, Paula Cunningham, Celia de Fréine, Anne Devlin, Moyra Donaldson, Wendy Erskine, Leontia Flynn, Miriam Gamble, Rosemary Jenkinson, Deirdre Madden, Bernie McGill, Medbh McGuckian, Susan McKay, Sinéad Morrissey, Joan Newmann, Kate Newmann, Roisín O'Donnell, Heather Richardson, Janice Fitzpatrick Simmons, Cherry Smyth, Gráinne Tobin, Margaret Ward, Tara West, Sheena Wilkinson, Ann Zell.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

FEMALE LINES

New Writing by Women from Northern Ireland

Edited by

Linda Anderson and

Dawn Miranda Sherratt-Bado

FEMALE LINES

First published in 2017 by

New Island Books

16 Priory Office Park

Stillorgan

Co. Dublin

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Editors’ Introduction © Linda Anderson and Dawn Miranda Sherratt-Bado, 2017

Individual Pieces © Respective Authors, 2017

An excerpt from Deirdre Madden’s Time Present and Time Past is reproduced by kind permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

An excerpt from Lucy Caldwell’s Three Sisters is reproduced by kind permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

The Authors assert their moral rights in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-642-1

Epub ISBN: 978-1-84840-643-8

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-84840-644-5

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed by

New Island is grateful to have received financial assistance from The Arts Council of Northern Ireland (1 The Sidings, Antrim Road, Lisburn, BT28 3AJ, Northern Ireland).

Contents

About the Editors

Foreword

Introduction

FICTION

Waste

Linda Anderson

Egg

Jan Carson

Locksmiths

Wendy Erskine

Time Present and Time Past

Deirdre Madden

Glass Girl

Bernie McGill

Wish You Were Here

Roisín O’Donnell

All the Rules We Could Ask For

Heather Richardson

Winning on Points

Tara West

Let Me Be Part of All This Joy

Sheena Wilkinson

DRAMA

Three Sisters

by Lucy Caldwell

On Writing

Three Sisters

Lucy Caldwell

The Forgotten

by Anne Devlin

Waking The Forgotten

Anne Devlin

Here Comes the Night

by Rosemary Jenkinson

The Hijacked Writer

Rosemary Jenkinson

PHOTOGRAPHS by Emma Campbell

POETRY

Jean Bleakney

Maureen Boyle

Colette Bryce

Paula Cunningham

Celia de Fréine

Moyra Donaldson

Leontia Flynn

Miriam Gamble

Medbh McGuckian

Sinéad Morrissey

Joan Newmann

Kate Newmann

Janice Fitzpatrick Simmons

Cherry Smyth

Gráinne Tobin

Ann Zell

ESSAYS

Rewriting History

Julieann Campbell

Sisters Are Doin’ It for Themselves: The Practice and Ethos of Word of Mouth Poetry Collective, 1991–2016

Ruth Carr

Thatcher on the Radio. Blue Lights Flashing up the Road

Susan McKay

Reflections on Commemorating 1916

Margaret Ward

Notes on the Contributors

Acknowledgements

About the Editors

Linda Anderson was born and educated in Belfast. She is an award-winning novelist (To Stay Alive and Cuckoo, both published by The Bodley Head) and writer of short stories, performance pieces and critical reviews. Her short fiction has been published in magazines and anthologies including HU, The Big Issue, Wildish Things, The Hurt World: Short Stories of the Troubles and The Glass Shore. She taught at Lancaster University, becoming Head of Creative Writing from 1995–2002. In 2006, she launched creative writing at the Open University, chairing the largest writing course in the UK until 2014. She was awarded a Fellowship by the Higher Education Academy in 2007. She is editor and co-author of Creative Writing: a Workbook with Readings and co-author of Writing Fiction. She lives in Cambridgeshire, writing fiction and non-fiction and working as an editor.

Dawn Miranda Sherratt-Bado is an academic and a dual specialist in Irish and Caribbean Studies. She has taught at Maynooth University, the University of Edinburgh, and the Scottish Universities’ International Summer School (SUISS). She is author of Decoloniality and Gender in Jamaica Kincaid and Gisèle Pineau: Connective Caribbean Readings. She has also published in Irish Studies Review, Breac, Dublin Review of Books, Callaloo, and The Irish Times.

Foreword

Linda Anderson

From Pipedream to Publication

It was just after Christmas in 2015 when I received an email from Dawn Miranda Sherratt-Bado, who was teaching at Maynooth University. Her purpose in contacting me was to invite me to co-edit an anthology of writings by contemporary Northern Irish women as a follow-up to Ruth Carr’s The Female Line: Northern Irish Women Writers, the pioneering anthology published in 1985. Dawn proposed a celebration of women writers across multiple genres along with an exploration of how much conditions have changed in the past thirty years and what sort of obstacles might still remain. My immediate impulse was to say yes. The Female Line felt like a breakthrough publication at the time but women writers remained significantly marginalised. While some writers included went on to become prominent, others have ‘disappeared’, even after brilliant debuts: for example, Blánaid McKinney, whose story collection Big Mouth, published by Phoenix House in 2000, was praised as ‘among the best short fiction to appear, anywhere, in the past year or so’. A novel followed in 2003 but nothing since.

I hesitated. I had edited a huge, multi-authored book before and knew how such a project takes over your life and consigns you at the end stages to obsessive forensics of lucid sentence arrangement and comma placement. I also knew that the idea was a pipedream due to recent funding cuts in the North. But the idea and the timing felt right. Sinéad Gleeson’s The Long Gaze Back had recently been published. Although we didn’t know it yet, its Northern sequel The Glass Shore was in the offing. The ‘Women Aloud Northern Ireland’ events were being organised all across the region for International Women’s Day in March 2016. And Dawn has a quality of intrepid hopefulness about her, which is inspiring.

During the New Year period in 2016, I decided to say yes and soon embarked upon a period of intensive research and collaboration with Dawn and the contributors, and renewed contacts with some writers I had last met around twenty-five years ago. For me, it has been a kind of homecoming.

I had personally found Northern Ireland injurious to my writing, even my desire to write. My first novel To Stay Alive (1984), although praised in Britain and the US and shortlisted for major prizes, was described on the BBC Northern Ireland radio arts programme Auditorium as ‘immoral and amoral’ and a ‘potboiler’. I survived that particular weekend by conjuring, almost channelling, John McGahern, remembering how he had to quit Ireland and his teaching job after publication of The Dark in 1965. Another local radio programme interviewed me about the novel, playing the theme tune from the screenplay of Gerald Seymour’s Harry’s Game as prelude. I was asked why I was bothered about Northern Ireland after not living there for twelve years. Then I was asked if I hoped to make a lot of money, from a film perhaps. So the introductory music was an insinuation, not any kind of tribute! There were less hostile responses, of course, but I was disappointed when that novel and the subsequent one, Cuckoo (1986), were often read either as thrillers or as part of the hopeless ‘doom and gloom’ mood of Troubles literature from the eighties. I thought they were more innovative than either category, more challenging of societal structures and assumptions.

One of the redemptive aspects of my involvement in this project has been to discover that my experience of being dismissed, whether through vilification or indifference, was common to Northern Irish women writers across the various genres – and that it stubbornly persists. But it is also evident that things are changing for the better. This is partly due to women’s own activism, such as the Word of Mouth Poetry Collective’s sustained development of women poets over a twenty-five-year period; the recent campaign, ‘Waking the Feminists’; and the ‘Women Aloud Northern Ireland’ programme of events, conceived initially as a one-off burst of energy, which has now run for a second time. The Arts Council of Northern Ireland has a commendable record of funding support for individual writers and for projects like this book. Several Northern Irish women poets are bringing out individual collections with Arlen House in 2017-18. Special thanks are due to Dan Bolger and the team at New Island Books, who have done so much to promote women’s writing throughout Ireland. In the space of three years they have brought out three anthologies, the prizewinning duo The Long Gaze Back and The Glass Shore, now joined by Female Lines. Dawn and I could not be more delighted.

Introduction

Linda Anderson and Dawn Miranda Sherratt-Bado

Texts and Contexts

In her memoiristic essay ‘Thatcher on the radio. Blue lights flashing up the road’, Susan McKay evokes Northern Ireland during the 1980s, the milieu in which The Female Line: Northern Irish Women Writers (1985) emerged. It was a site permeated by ‘“The Violence”, as it was called,’ a place of sectarian and gendered violence where ‘armed patriarchs’ and ‘warzone women’ clashed. Amidst the conflict, the Northern Ireland Women’s Rights Movement marked its tenth anniversary by publishing The Female Line, the ‘first collection of writings by Northern Irish women writers,’ edited by Ruth Hooley (now Carr). This ground-breaking publication was a remarkable feat considering, as Carr notes, ‘The Troubles [were] never … very far from the door.’

2015 marked the thirtieth anniversary of The Female Line and it felt vital to publish an updated anthology which would explore conditions for women in Northern Ireland post-ceasefires, post-peace process, and post-Good Friday Agreement. What does it mean for women to write in a time of ‘post-conflict’, and what effect does this have on their work and on their lives? 2015 was also the advent of the ‘Waking the Feminists’ movement in the South. This begged the question of how much has changed or stayed the same in terms of scope and opportunity for women authors from Northern Ireland. Furthermore, in the wake of the 2016 Brexit referendum, and the collapse of the Northern Ireland Assembly and the UK snap election in 2017, Northern Ireland’s global position is once again precarious. Despite these circumstances, women writers from the North are flourishing due to more public platforms and greater publishing opportunities. Female Lines distils some of the powerful energy surrounding Northern women’s writing, while also addressing the legacy of The Female Line which, as Carr remarks, ‘is both handed down and self-written’.

In Female Lines, we trace the inheritance of the original anthology and follow its example by presenting a mosaic of new work by contemporary women authors from the North. This book captures a wide range of styles, forms, and perspectives and it includes short stories, flash fiction, extracts from plays and one novel, photographs, poetry, memoirs, and reflective essays. It showcases the work of thirty-two Northern women authors (thirty-one living and one deceased) and a photographer. The book features newly commissioned pieces wherever possible. Where this was not possible, we included the author’s most recent work.

As a method of approach we consulted The Female Line, in addition to the anthologies of Irish women writers that followed in its wake: Wildish Things: An Anthology of New Irish Women’s Writing (1989), edited by Ailbhe Smyth; Wee Girls: Women Writing from An Irish Perspective (1996), edited by Lizz Murphy; The White Page/An Bhileog Bhan: Twentieth Century Irish Women Poets (1999), edited by Joan McBreen; Cutting the Night in Two: Short Stories by Irish Women Writers (2002), edited by Evelyn Conlon and Hans Christian Oeser; Sinéad Gleeson’s edited collections The Long Gaze Back: An Anthology of Irish Women Writers (2015) and The Glass Shore: Short Stories by Women Writers from the North of Ireland (2016); Washing Windows? Irish Women Write Poetry (2017), edited by Alan Hayes. For further research on the contemporary Northern Irish context we read widely, and the range of texts included two monographs which appeared serendipitously in 2016: Fiona Coleman Coffey’s Political Acts: Women in Northern Irish Theatre, 1921-2012 and Birte Heidemann’s Post-Agreement Northern Irish Literature: Lost in a Liminal Space. What emerged from this period of research was the sense that Northern women writers have grown in confidence, numbers, and reach. The parameters for selecting contributors were that the writers were born or currently reside in the North, or that they have cultural or familial connections to it.

Fiction: The necessity of risk

‘There is no point in making a thing … if there is no emotional risk to it.’ So says Liam, a college tutor in Bernie McGill’s story ‘Glass Girl’. And risk is a hallmark of the fictions included here, whether in subject matter, form or tone. ‘Glass Girl’ is a quietly passionate story about bereavement that shows the healing power of art and of sisterly love. A very different story, also about loss, is Roisín O’Donnell’s ‘Wish You Were Here’. Her keynote magical realism is at work in this story but it is digital technology that performs the ‘magic’ – by fabricating an ongoing ‘interaction’ with a dead father as a means of trying to circumvent mourning. Jan Carson’s fable-like ‘Egg’ uses metaphor in her characteristically playful yet profound way. A mother gives birth to a baby who is clutching a bird’s egg. She devotes herself to watching over the egg to the neglect of everything else. Does this conjure the currently stalled rebirthing of Northern Ireland or the power of any beguiling but paralysed potential to lay waste to a life? Similarly rich in allusion and reach is Heather Richardson’s ‘All the Rules We Could Ask For’. This is a sophisticated ‘anti-story’ with a godlike narrator who talks condescendingly about characters as if they are mere story ingredients as they are herded on to the red or blue staircases of a ferry about to set sail. It’s a story all about limits and containers, the things that control us. Two urban stories that are notably set away from tourist-trail Northern Ireland are Wendy Erskine’s ‘Locksmiths’ and Tara West’s flash fiction ‘Winning on Points’. ‘Locksmiths’ is set in an area of Belfast where violence, crime and incarceration are matter-of-fact. The dialogue between a mother and her disenchanted daughter vibrates with unspoken resentments. The daughter has embraced DIY, doing up the house left to her by her grandmother. But DIY is shown to be something deeper: autonomy, doing it for herself, turns out to be a survival strategy. ‘Winning on Points’ is a savage tragi-comedy about an expert form of loserdom, showing how the benefits system fosters an investment in maintaining ill health. Only two stories deal directly with the aftermath of the Troubles. In Linda Anderson’s ‘Waste’, a district nurse from Northern Ireland is weighed down by traumatic memories from the conflict but no one in her adopted England is interested in hearing her stories – until she comes across someone who does want to know – for all the wrong reasons. We have included only one novel extract, from Deirdre Madden’s Time Present and Time Past, which explores how a middle-aged brother and sister come to terms with their pasts, including an estrangement from the Northern strand of their family. Harking back to earlier national turmoil, Sheena Wilkinson’s ‘Let Me Be Part of All This Joy’ is set in a girl’s boarding school in Belfast after World War I, the Rising, and the partitioning of Ireland. It is a gentle comedy with a light, satirical touch – but with chasms of unarticulated sorrow underneath.

Drama: Very public platforms

The three playwrights included in Female Lines are also writers of fiction and have had their stories featured in The Long Gaze Back and/or The Glass Shore. Showcased here are two stage plays which premiered at the Lyric Theatre Belfast: Three Sisters, an adaptation from Anton Chekhov by Lucy Caldwell and Here Comes the Night, written in response to the Easter Rising centenary by Rosemary Jenkinson and containing her characteristically dark and witty criticism of current-day Northern Ireland. Anne Devlin’s radio drama The Forgotten was broadcast in 2009. It explores the influence and weight of what is forgotten through the crises of Bee, an artist whose health and finances are collapsing, forcing her to move back to her mother’s home.

We have included an opening extract from each play to provide the set-up and atmosphere, accompanied by specially commissioned essays describing the inspirations behind the plays, the processes of making them, and their reception. These personal essays provide fascinating insights into how plays are made. Anne Devlin, for example, describes the importance of anchoring each scene in a specific soundscape in radio plays. In the complex process of adapting a classic play, Lucy Caldwell pinpoints the need for some true and vital connection between it and its transposition to a new setting: ‘To be true to the play, I needed to be much truer to my new setting.’ Rosemary Jenkinson highlights the importance of a shared vision of the play with a responsive director. All three refer to incessant rewrites.

These writers also recount their personal experiences of the marginalisation of women playwrights. Caldwell and Jenkinson describe the band of local reviewers as particularly narrow-minded and begrudging towards plays by women, while Devlin sums up the process whereby the work of women playwrights goes out of print, is not revived, and gradually vanishes from the canon. Both Devlin and Jenkinson highlight the reinvigorating impact of the ‘Waking the Feminists’ movement, started in Dublin in late 2015. The theatre scene in Northern Ireland looks poised at a crucial moment of potential change. Other audacious talents, such as Stacey Gregg, Abbie Spallen, and Shannon Yee are beginning to have their work more welcomed in the North, instead of having to be feted and staged outside of it.

Photography: Perspectival Shifts

The practice of fine art documentary photography developed as a reaction against the misrepresentational imagery of the North which circulated in mass media during the first decade of the Troubles. However, the photo-documentary mode was traditionally a male-dominated artistic practice in Northern Ireland. This occlusion of women’s visual narratives of the conflict continued into the peace process and it paralleled the general lack of attention to women’s perspectives within a patriarchal milieu. However, in the post-Agreement moment women photographers are responding to this effacement by addressing gendered viewpoints, as well as socio-political issues that affect women directly. Accordingly, contemporary photography galleries throughout the North also help to advance opportunities for local women photographers by commissioning, showing, and publishing their work. Female Lines features images from Belfast-based artist and activist Emma Campbell’s photo-documentary series ‘When They Put Their Hands Out Like Scales: Journeys’, which promotes the visibility of women who journey across the Irish Sea for an abortion. Abortion is only legal under strict criteria in Northern Ireland and Emma’s work interrogates the ways in which the issue of reproductive rights and the figure of the abortion seeker are framed within post-conflict public life.

Poetry: A larger elsewhere

One of the sixteen poets featured in the book, Mebdh McGuckian, was included in the original The Female Line. In the early nineties, she went on to be sometimes the sole female inclusion or one of a tiny percentage of women poets included in the notoriously closed shop of Northern Irish anthologies. We are glad to feature four poets who were members of the Word of Mouth Poetry Collective founded in 1991 by Ruth Carr and Ann Zell, partly in response to this silencing, dedicated to the development of their own and other members’ poetry. They are Joan Newmann, Kate Newmann, Gráinne Tobin, and the late Ann Zell. We include some of Zell’s ‘Donegal poems’, which evince love of that coastal landscape and its wildlife and are also suffused with a sense of her rural past in Idaho. We are able to include these poems thanks to the enterprise of Ruth Carr and Natasha Cuddington, who published the collection Donegal is a red door (Of Mouth) shortly after Ann Zell’s death in 2016.

Many other poets here also depict local places with precise and painterly detail. We have Jean Bleakney’s witty lament for the relocation of the Balmoral Agricultural Show (‘After the Event’); Gráinne Tobin’s view of a grand house in Ballynahinch (‘Passing Number Twenty’); Kate Newmann’s elegiac ‘The Wounded Heron’. Cherry Smyth takes us down a road in Ballykelly to Shackleton Barracks and straight into hell in her reimagining of what was done there in 1971. There is often too a reach beyond the North and beyond Ireland, for example in Celia de Fréine’s trilingual engagement with Rainer Maria Rilke’s poems in his French-language collection Migration des Forces; Cherry Smyth’s unflinching account of a failing relationship in Lisbon; Sinéad Morrissey’s multi-voiced dramatic poem ‘Whitelessness’ with its team of scientists and artists on a climate change research expedition in Greenland. Breadth of focus is also evident in poems inspired by history, myth and legend: we have Joan Newmann’s triptych of literary figures; Kate Newmann’s incantatory ‘The Leviathan of Parsonstown’ in which astronomical advance is pitted (literally) against the tragedy of the Famine; Colette Bryce’s tender portrayal of St Columba in ‘The White Horse’; Janice Fitzpatrick Simmons’ warrior ghosts in ‘View from Black Pig Dyke’ merging with modern atrocities. Personal poems include a number of portrayals of beloved fathers assailed by disease or dementia. Maureen Boyle’s narrative poem ‘Bypass’ casts herself and her mother as anguished relatives and enforced tourists when they accompany her father to London for heart surgery. Paula Cunningham in ‘Fathom’ uses the imagery of ‘Ariel’s Song’ from William Shakespeare’s The Tempest: ‘full fathom five thy father lies’, in an unusually upbeat poem in the face of memory loss. Miriam Gamble’s ‘Bow and Arrow’ takes a different approach, portraying her father as a boy shadowed unknowingly by an accident. Leontia Flynn’s Forward Prize-nominated ‘The Radio’ depicts a mother perpetually fearful for her family’s safety on their isolated farm during the Troubles. Constant news from the radio penetrates her strained body and mind. Motherhood is shown as ‘a heart of darkness’, a nonplussing burden shot through with jagged alarms. It is true to many people’s experience of the height of the Troubles: influxes of terror via the news every hour on the hour. Motherhood as unrelieved anxiety is also one of Moyra Donaldson’s themes in ‘The Sixtieth Year of Horror Stories’ and in ‘Mare’. It is not possible to give details of every poem included here but what is important to indicate is the extensive range of subjects and the fact that the chief delight of these poems lies in the singularity of each poet’s voice.

The essays: No more hidden histories

Margaret Ward’s ‘Reflections on Commemorating 1916’ explores the centenary celebrations of women’s contributions throughout the whole of Ireland, outlining the contradictions of an honouring of women’s participation while excluding women historians from speaking on panels or at events. Quoting Adrienne Rich, she warns against the erasure of historical evidence of women’s activism, something that deprives women of a sense of tradition and role models.

The four essays assembled here may well function as a repository of such evidence. It was not pre-planned or anticipated but the essays here all contain hidden histories or side-lined stories as well as insights about campaigning for change. Ruth Carr’s account of the role of the Word of Mouth Poetry Collective in developing the work and careers of its member poets (‘Sisters Are Doin’ It for Themselves’) is a case of twenty-five years of helping bring forth poetry that might otherwise have been consigned to silence. This essay truly gives a sense of different voices and experiences and captures the atmosphere of the best kind of writer’s workshop practice, at once so charged and so disciplined.

One striking aspect of Julieann Campbell’s ‘Rewriting History’ (about the ‘Unheard Voices’ project based in Derry) is the way in which she brings out the ongoing distress of survivors of violence, both the injured and the bereaved. We usually remember the iconic dead but know less about the everlasting pain of witnesses and survivors. One survivor of the Greysteel massacre says: ‘It feels like I and my mother weren’t even there.’ Susan McKay’s memoir of working in a Belfast Rape Crisis Centre during the eighties – ‘Thatcher on the radio. Blue lights flashing up the road’ – uses a patchwork method of mixing diary entries from the time with present-day reflection, adding vividness and authenticity to her account. Both of these writers describe the deep emotional toll of constant exposure to the suffering of others, what Susan McKay calls ‘vicarious traumatising’. McKay and Carr also write honestly about the rifts and divisions that could flash within their respective groups, threatening their stability or even their continuing existence. Not for the fainthearted, which brings us back to where the book fittingly ends – with Margaret Ward’s reminder of the transformative potential of women’s activism and the need to always guard against the suppression of the evidence.

The trouble with anthologies

There is a gap of thirty-two years between the publication of The Female Line in 1985 and this anthology, conceived as a response and staging post. We would appeal for more anthologies, with all kinds of different missions and reaches. Otherwise, there is a risk in the way that anthologies are seen as constructors of a canon. They can be used to cement existing hierarchies and unknown absences. There are other writers who could also have graced these pages, if only there were room enough. We pass on the torch.

FICTION

Waste

Linda Anderson

Her house was astonishing. None of the usual old-lady cushions and fringed antimacassars and little pictures and china cabinets. Her rooms were stark and spacious, furnished with overbearing items. Two grandfather clocks daunted me at once. So august and upright and with those weighty pendulums swinging away, drawing attention to themselves. A baby grand piano with the lid up. Who lives here, I wondered, picturing a severe regal person, obviously someone used to keeping people waiting. ‘Mrs Ball, it’s your district nurse,’ I called out as I had done upon entering by the prearranged unlocked door. Just at that moment the clocks chimed importantly and asynchronistically. It was as if one was goaded or reminded by the other but then could not catch up. What a racket! I looked around downstairs. The bossy grandeur of the place could not hide an air of neglect. There was a talcum of dust on the fine tables and chests. On the windowsill, segments of a dead wasp, curiously divided.

I ventured upstairs as noisily as possible, calling out her name, trying to keep embarrassment out of my voice. It is hard not to feel a sense of trespass when you enter the homes of strangers. The bathroom – another surprise. It was white. White tiles, white carpet, white bath, white toilet, white bidet, total clinical whiteout. There was even a white clock, a timepiece too far, in my opinion, in a house where the disappearing moments were already being announced every half hour (as I soon discovered) in the strident double act downstairs. Poor thing, I thought. Imagine being immobilised in this house listening to time draining away. I pushed the bedroom door and there was Mrs Zara Ball, propped up in bed with a hideous dog snoozing away on the pillow.

‘Well, there you are,’ I said with the kind of managerial cheer that usually works.

‘Never anywhere else at this hour of the day. You’re too early!’

‘It’s quarter past ten.’

She waved a hand dismissively.

‘I understand you’ve got a problem with some varicose veins, a bit of ulceration? … I’ll change your dressings up here. No problem. Then I’ll help you downstairs, if you like.’

She lifted up her great swaddling duvet so that I could peel the old compression bandages off her spindly, blue-snaked legs. The dog farted squeakily. Mrs Ball chortled then whacked him when the sulphurous odour reached her. ‘Casper! Filthy animal!’ It amazed me that the owner of the dazzling bathroom would share her bed with this unhygienic mutt. I watched him as I went about my cleansing and bandaging. He was a bloated poodle with the same dank tallowy hair as his owner. No barking, no tail wagging, no curiosity or hostility for the intruder. He was obviously her captive. A denatured dog, toxic with tinned meat. A dog with all doggy liveliness and inquisitiveness bored out of it. It repelled me with its distended gut and rank odours. Though I felt sorry for him, too, and even thought of offering to take him for a waddle over some real grass.

Don’t get involved, I thought.

It was less disconcerting to contemplate his appearance than his owner’s. Mrs Ball was a gaunt creature with a noble, aquiline face in repose. But when she talked, she could suddenly look like a mad hen with glittering, dead eyes. Unfortunately, she was appraising me critically too.

‘You look a bit hale and hearty,’ she said slyly.

‘It’s the cycling. I bike everywhere.’

‘Bit broad in the beam, aren’t you, despite all your exercise?’

I said nothing. I had already experienced quite enough below-waist attention from an earlier patient, one of those dirty-sad old men who lose their inhibitions along with everything else.

‘They ruin your figure, don’t they? Little sods.’

‘What?’

‘How many have you had?’

‘How many what?’

‘Children! Offspring!’

I didn’t answer, which did not deter her speculation.

‘You look like the mother of a big brood. I can just see you all in your various uniforms. You in that get-up with your pocketful of pens and your thermometer and them in their comprehensive school ones. Going round the supermarket like a Girl Guide troupe.’

‘So you imagine me as the mother of girls?’

‘Can’t see you handling a lad,’ she leered.

‘I have no children,’ I said. It came out like an admission of guilt. ‘I’m a career woman.’

‘That’s interesting. What was your career? Why did you give it up for this?’

She sounded so mean and merry. I felt about twelve years old. I quashed the impulse to blurt out that I had two degrees.

‘How about you? Diplomatic service?’

‘I was a kept woman!’ she said triumphantly or defensively, I wasn’t sure.

‘What a waste!’ I said.

Or what a mercy. All that waspishness confined to the home.

‘It was hard work.’

‘I’m sure it was.’ Especially for Mr Ball.

The career woman careered downhill on her bike (ecologically sound choice of transport, of course. Could easily afford a car blah blah), to her next appointment. She raced through the town, through her private map of it in which she linked each area’s preferred form of pet ownership with different kinds of ailment. Here we’re leaving the pooches ‘n’ piles belt, heading through paranoia ‘n’ reptiles down towards pigeons ‘n’ angina.

Ha, bloody ha, I thought that day, after the Ball. That little encounter made me see myself all too clearly, me and my pathetic jokes, an attempt at superiority, me and my vaunted career. I was cheapskate community care, hired friend of the friendless, a shit-scraper. The housebounds were usually so glad to see me. I knew how to make myself chatty and cheerful, incapable of disgust as I assisted with various intimate necessities. I had trained myself not to flinch from ugliness. Yes, show me your warts and wens, your papery breasts, your acorn-studded limbs, your yellow eyes. I am Mrs Nursey Nice with a big valise crammed with soothing secret things – adult nappies, colostomy bags, dressings, and an array of salves and unguents that stink like a mixture of bonfires and sherry. Mrs Ball had managed to make me feel like the naked one and I didn’t like it. She had not just sneered at my job; she had pried and poked into my life. Served me right probably for being some kind of thief, a stealer of privacy. My patients had no choice but to expose their failing flesh to me. Some of my death’s doormen thought I should return the favour and I would have to swat many a sly lizardy hand sneaking up my blue cotton skirt. Like Mr Todd earlier that day with his up-and-under dive followed by smug impish looks. Those wizened flirts disturbed me despite my shockproof style. It was something to do with the way they held on to sexual hope, no matter how risible, importunate, or routinely rebuffed. That was impressive. But I found it galling to get offers from the drop-dead-any-minute when I was still susceptible to the drop-dead gorgeous. From whose point of view, my longings would be as clownish and misplaced as the geriatrics’ gropings of me. Inappropriate, that’s the word, the quelling word. Most of what happens to bodies, to persons, makes mischief with the notion of appropriateness and I know that. In my line of work, how could I fail to know that? But I could not remember ever having done a wild indecorous thing and I felt bereft. I felt ridiculous too for feeling so much, for letting the old bat get to me.

Just as I was getting off my bike, I saw something wonderful. A girl with two minky brown Labradors hurtling by. She was on roller-skates, holding the dogs’ leashes in either hand. The dogs were exuberant and bounding but she controlled their speed while propelling herself along with a sure grace. They flew like Boadicea and her horses. I was captivated by this vision … and just as suddenly crushed. There I was, so heavy and grounded and middle-aged. Like a statue forced to breathe. I had never been that girl. I had never given birth to such a girl either. God, where did that come from? I was feeling something alien, utterly unfamiliar. Now the old harridan was making me miss some phantom daughter! Images of our life together began to assemble swiftly: the Christmases, the school reports, the PTA meetings, the trips to McDonalds, the crises of puberty. My life, my real life, was so calm and eventless, it made me dizzy. My marriage had been short-lived, more of a matrimonial episode, or possibly an inoculation, to a man, suitably called Rob, whose face was coming back to me, his woeful handsome face with the frown scored into it like a wicket … Rob the spare-time lay preacher who lost religion but retained the fault-finding zealotry. His insults poured back: Why don’t you lighten up? Why do you have to disagree? Must you wear that thing? Why do you have to analyse me all the time? Why do you always have to be on top? Unfortunate phrasing seeing as he was forever complaining (complaining also) about my sexual conservatism.

Stop right there, I told myself. Mrs Ball was just a sour bully. I was giving her too much power over me. This was to do with a lesion in my pride from the past. Also, I was softened up by too many placid patients. Tomorrow I would armour myself with robust professionalism. Compassion even. A bit of mercy was probably in order, after all, for that bitter old bag whose antagonism was probably reflexive, entirely impersonal, just a way of staying interested in life.

The dog was waiting silently at the door next morning when I arrived ready to out-tough his owner. He raised his foggy pleading eyes but I was determined to ignore the weakened mutt. Mrs Ball was seated at the table, clipping something from a newspaper. She must be better? Of course, her poor ulcerated legs would have made her ill-tempered yesterday. ‘What’s this?’ I asked recklessly, expecting to see a collection of pious poems, gardening tips, cures for arthritis, pictures of royal persons. How easily my docile old-dear expectation revived itself! She leaned back to allow me to leaf through her album, which was stuffed with items about deaths. Deaths of strangers. British, European, American, whatever. Mostly described in the spare poignant detail of newspaper reports.

Mrs Ball collected deaths.

She brandished her new cutting. A honeymoon couple drowned while swimming in a river. Unaware of the dangerous currents … perhaps one drowned trying to rescue the other …

‘That’s tragic,’ I blurted.

Mrs Ball was serene. ‘Not what they expected, that’s for sure.’

‘Why? Why on earth do you want to compile this stuff?’

She shrugged. ‘I like research. I like collecting. I like jokes.’

‘Jokes?’ I gasped.

She pushed the album towards me again. ‘I defy you not to laugh at least once.’

All the deaths were spectacularly pointless, bizarre, or farcically ignominious. No common-denominator passings. None of your peacefully-at-homes. Famous-people-bite-the-dust seemed a favourite. Oh yes, Zara Ball enjoyed the grim demises of uppity celebs. There were more than thirty years’ worth. John Lennon was in there, Elvis upon that toilet, Princesses Grace and Di, Monroe, Mansfield, all the blondes, Amy and the other addicts, the Electric Light Orchestra cellist eliminated by a half-tonne hay bale bursting through a hedge to land on his car roof … She was also interested in lowly deaths, so long as they were ludicrous. I noticed that everything was methodically grouped. The woman was like death’s secretary, entertainments division. The categories seemed to be:

Self-sacrifice for trivial causes. The elderly woman who torched herself because she could not look after her garden. The man who was stargazing on his balcony with his beloved Chihuahua when a sudden meteor shower startled the dog into springing out of his arms and plunging several floors to its death. The inconsolable owner drowned himself in a nearby river. Hee haw.

Deaths following outstanding success or happiness. The student who gained the highest ever marks in his university’s science examinations, and hanged himself. Brides or grooms who snuffed it on honeymoon, or preferably at the reception. (Today’s bit of post-nuptial nemesis would slot in nicely.)

Bizarre methods. The man who drilled holes in his skull with a Black & Decker. The woman who committed suicide by drinking fifteen litres of water.

Lucky escape followed swiftly by termination. The American translator whose car was blown into a river during a storm. She managed to extricate herself and swim to shore, where a tree crashed on top of her, killing her outright. The Japanese man who escaped with minor injuries when his house collapsed in an earthquake. After treatment, he returned to search for important documents. The one remaining wall fell on him, bye-bye.

Machismo beyond the point of duty. The Polish farmer who was drinking with some friends when it was suggested that they strip naked and play some ‘men’s games’. This began mildly with them hitting each other over the head with frozen turnips. One man escalated the contest by grabbing a chainsaw and slicing off the end of his foot. ‘Watch this, then,’ shouted the heroic farmer, seizing the saw and cutting off his own head.

I slammed the book shut. ‘Perhaps those of us who are not dying had better get a move on,’ I said, getting the bandages out.

‘Oh dear, not even a titter,’ she mock-pouted. ‘Hah, we’re all dying, every minute. Only one end to the story. You should know that better than anyone.’

I thought she meant because I was a nurse. But she meant because I came from Northern Ireland, with its industry of stupid sudden exits. And over the next few days, she started probing. And I started acceding. Adding to her hoard. Pandering to her. The first one I told her about was the chief inspector in the RUC who survived gunfire, escaped with his life several times. The policemen at his local station fed themselves with takeaways from the nearby chippie. One day the inspector slipped and fell in the station porchway, hit his head and died. It was the slow lethal accumulation of grease drippings from the takeaways that had made that patch of floor so perilous. His own colleagues had killed their boss. Mrs Ball loved that one. It had the most thrilling ingredient – the high-status person brought low in the most unforeseen and undignified way.

Then there was the one about the woman who persuaded her husband to emigrate to Australia to obtain a better future for their children, far from all the bigotry and violence. Years later, she happened to be shopping in Sydney and stopped to watch a demonstration in support of the Irish hunger strikers. A sudden gust of wind caused a banner-holder to drop his flagpole. It struck the woman on the head … ‘Killing her outright,’ we chorused together – she knew the exact moment to chime in. I looked at her contented eyes and her hands clasped like a child’s. She’s mad, I thought. What’s your excuse?

The more Mrs Ball liked me, the more I disliked myself. Was I so easily cowed by this curmudgeon that I would do anything to sweeten her up? Would I start telling porn stories to my lechers next? Why not? The district nurse who dispenses a daily dose of the obscenity of your choice. Why did I go on propitiating her? I started to wonder if her steeliness fascinated me. No news of suicide bombers or sunken boats would put this lady off her breakfast. Perhaps sheer heartlessness kept her going. After all, her legs were leaking. Her ribs cracked if she sneezed hard. She was crumbling millimetre by millimetre. Maybe she needed to forestall her own death, even as it crept over her. Or maybe she was just bored. Sometimes she would yawn like a cat, showing her stumpy little molars. Her existence might be one long dull sentence enlivened by a bit of Schadenfreude. Whatever the truth of it, I was scared of her, especially when I was not in her presence. She became Mother Time in her clock-crammed house. A leering tricoteuse. Skeletal Lady Death wielding her fateful scissors. Then I would see her and she would revert to human scale. Her Woolworth’s scissors with little slivers of sellotape adhering to the blades. Her matted cardigans, her faintly vegetable odour. Her lumpy dog who sometimes snored during my rending stories. What a companionable trio we were. I had begun to talk to the dog when he was conscious or semi. I even fondled the blubber on the outposts of his being. Casper was too silly a name. I whispered Wolf to him like a secret code, trying to lure him back to doghood, to a state of grace. Wild boy, I said. Come on, Wolfie, bark like a dog, will you?

I kept on with my stories: the murdered by mistake; the poked to death by snooker cues; the hapless wanderers into the wrong bar … I was a funerary Scheherazade. Tacky, craven, and wrong. But I could not stop my ignoble threnody. Sometimes I wondered if I was getting relief from it, an illicit unburdening. Most people did not want to know about violent Irish deaths. Mrs Ball provided an audience, however cold-hearted. But one morning, mid-tale, I had a sudden memory of my friend Ruth’s daughter, Ellie, when she had just turned ten. I had gone round one evening to see Ruth and after some wine and chat, we decided to watch a television documentary on Colonel Gaddafi. Ellie was sitting at the table, drawing. I suppose we thought she was in her own world, tuned out, but the truth is we hadn’t thought at all. Just as the presenter described how Gaddafi had murdered his foreign secretary, then stored the body in the palace deep-freeze, so that he could enjoy a regular gloat over it, Ellie vomited, a great jet of sick erupting from her without warning and without strain. I envied her. For her intact humanity, her inability to conceal and her inability to accept.

I’m stopping this shit … this compliance.

I told Mrs Ball one more story, from my own family history. My great-grandmother nursed her son, Archie, through a life-threatening bout of pneumonia. She and his aunts and his sisters kept vigil over him night after night, cooling his brow, helping him breathe, praying. The doctor said there was no hope. But Archie recovered. Suddenly returned to himself, got up out of bed, shaky and renewed. His family rejoiced. Archie went down to the army recruiting office, lied about his age, joined up, and was killed at the Somme a couple of weeks later. His mother died of grief.

‘Don’t they always?’ Mrs Ball interrupted. His sister, I kept on, my grandmother, then lied about her age in order to emigrate to Canada. She was depressed for the rest of her life. Mrs Ball looked at me with haughty discontent and said nothing. The story fitted the criteria but my tone was wrong. I was insisting on the waste, the agony, the consequences.

‘That’s not one for the collection,’ she said finally. ‘That’s one of those women-moaning-about-men stories. Spare me that, if you don’t mind!’

I was the one who found her. It was just three weeks later. She was sitting neatly in a chair, her spectacles in her lap. Natural causes. She got off with an ordinary statistical death. Perhaps she would have found that inglorious, I don’t know. It was certainly deficient in comedy. While I waited for the doctor and for social services, I secreted the album (wasn’t it ours now?) in my valise.

‘She looks emaciated,’ the doctor opined. He sounded accusing.

‘I don’t think she had much appetite,’ I said. ‘But she had meals-on-wheels every day.’

‘Did she eat them?’ he asked caustically.

‘I was only here for a half hour each morning.’

He relented. ‘Her daughter died that way, you know. Self-starvation. Thirty-five years ago. She weighed four stone at the end. Zara did everything she could. Begged, bribed, forced the girl into hospital, left her alone, refused to leave her alone … And the girl dwindling and disappearing all the time …’

Wolfie whined and I said suddenly: ‘I think I’ll take him out of here for a while. Maybe I’ll look after him tonight. Until something can be decided.’

‘That would be kind. I wouldn’t hold out much hope for him, though. No one will want to take on that pathetic lump.’

I knew where the redundant leash was hanging and hurried to get it, afraid that I might faint if I did not get outside. I heaved Wolfie into my arms and deposited him in my bicycle basket, where he stayed during the rest of my rounds, quivering like a lightning rod. Each time I reappeared from some doorway, he howled in a mixture of protest and relief. Back home I sat looking in disbelief at my newly acquired encumbrances. That woman’s dozy dog and vile scrapbook! She had probably destroyed her own daughter. Put her on a diet at eight years old, most likely. I remembered Mrs Ball’s contempt for any sign of spare flesh. The girl dwindling and disappearing all the time … Served her right, oh yes. But then I began to imagine it. The girl unstoppably capsizing herself and her mother. For good. Forever. Really, I had understood nothing. Couldn’t, wouldn’t, didn’t see the terror and rage behind Mrs Ball’s masquerade. Never once did I see Zara (Zara!) bleed through her mask.

‘You can’t trust me, Wolfie,’ I said and he moaned. I guessed he must be hungry. A safe bet with Wolfie. I found some ham and chicken slices for him in the fridge and bulked it out with potato salad. The death album was sitting on the table. I flicked through the pages. Away from Zara’s necrophiliac zest, they seemed just a pile of random sad stories. They needed nothing from me, no compensatory reverence. But I needed to do something. Wolfie was settling into his post-prandial snooze when I put the leash on him. ‘New regime,’ I told him. ‘Meal, then exercise. You’ll get to like it.’

We climbed the hill up to the park. Wolfie could not believe his escape from custody. He snuffled the leaves, groaned ecstatically at the breeze. We started to walk faster and then broke into an enfeebled run. ‘That’s it, Wolfie!’ When we were out of breath, I stopped by a gigantic sycamore tree. Wolfie sniffed voluptuously at the dog pee, all the urinary telegrams from his lost tribe. His joy, so simply returned to him, made me laugh out loud. I took out the album and began to rip and dismantle it. I flung the pages, the yellow curled ones, the fresh white ones. The wind whipped them into the air or chivvied them over the ground. Wolfie looked at me, inciting me to start walking again. We were elated with the unrecognisability of ourselves. From the top of the hill, I looked back at the deaths. They were flying away, far away from all gloating or grieving.

Egg

Jan Carson

You were born with a bird’s egg tucked inside your hand.

It looked like a starling’s egg, but it could just as easily have been a robin’s. They are a very similar shade. Your eyes are the same high August blue. You are also lightly freckled.

At first, I did not notice the egg. I was drunk on the just-born smell of you. Your foldable arms, your ears, and feet – which were just like adult feet, only greatly reduced. I was worn out from all the pushing and shoving. Then, the sudden rush of you, coming in a flood at the end.

‘This is really happening,’ your father said. And just like that, it was already over.

You came thundering out of me fist-first. Fingers curled round your thumb, tight as a walnut shell. After your arm came your head, a second arm and a single torso, a pair of pancake-flat buttocks and two legs with feet like full stops clamouring on either end. You were all there. Every bit of you in the proper place and working. Every bit but your left arm, which stayed stubbornly up for almost a week.

‘He’s ready to punch anybody that gets in his way,’ your father said, and laughed like this was a good thing. I didn’t think it was. You seemed far too furious for a brand-new person. ‘Is this normal?’ I asked. It was not normal. The midwife had never delivered a fist-first baby before.

‘Don’t panic,’ she said. ‘He seems fine. I’ll just check him over to be sure.’

Then, she whisked you away for weight and length and swaddling in a clean, white blanket. When you returned, you looked exactly like babies are meant to look. All blink-eyed and freshly pink. If I held you right I couldn’t even see your strange arm sticking up from under the blankets.

‘Isn’t he perfect?’ I said.

Your father didn’t reply. His face was trying not to fold.

‘What’s he holding?’ he asked, unpeeling the blanket to examine your curled fist.

‘Nothing,’ I said. ‘It takes babies a while to uncurl. He’s been bunched up inside me for nine months. No wonder he came out funny.’

‘I think he’s holding something,’ your father said. He could see the pale of it glowing between your fingers.

I took your little nugget of a hand in my own and began to unpeel your fingers. I went at you slowly, gently, like tiny steps on ice. Baby fingers are brittle as bird’s legs. I didn’t want to snap you. It took a minute, maybe ninety seconds to prise your hand open. Your father and the midwife hung over me, holding their breath as if just the thinnest puff of it might break you. I could see parts of the egg straightaway but I didn’t say anything until it was fully exposed.

‘It’s an egg,’ I said. ‘The baby’s come out holding a bird’s egg.’

No one spoke. There wasn’t even a peep out of you.

I lifted the egg up and held it, very gently between my finger and thumb. It was almost like holding air. So light. So easy to ruin.

‘This was inside me,’ I said. ‘How did it get there?’ My own voice was swimming away from me. I thought I might faint.

‘Did you swallow it?’ asked the midwife. ‘No, that makes no sense. How would the baby get hold of it?’