Femen E-Book

17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

'Ukraine is not a brothel!' This was the first cry of rage uttered by Femen during Euro 2012.

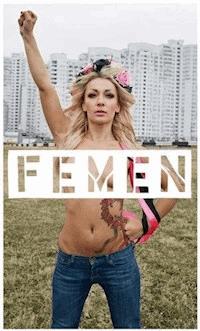

Bare-breasted and crowned with flowers, perched on their high heels, Femen transform their bodies into instruments of political expression through slogans and drawings flaunted on their skin. Humour, drama, courage and shock tactics are their weapons.

Since 2008, this 'gang of four' – Inna, Sasha, Oksana and Anna – has been developing a spectacular, radical, new feminism. First in Ukraine and then around the world, they are struggling to obtain better conditions for women, but they also fight poverty, discrimination, dictatorships and the dictates of religion. These women scale church steeples and climb into embassies, burst into television studios and invade polling stations. Some of them have served time in jail, been prosecuted for ‘hooliganism’ in their home country and are banned from living in other states. But thanks to extraordinary media coverage, the movement is gaining imitators and supporters in France, Germany, Brazil and elsewhere.

Inna, Sasha, Oksana and Anna have an extraordinary story and here they tell it in their own words, and at the same time express their hopes and ambitions for women throughout the world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 297

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

FEMEN

FEMEN

BY

FEMEN

With Galia Ackerman

Translated by Andrew Brown

polity

First published in French as FEMEN © Éditions Calmann-Lévy, 2013

This English edition © Polity Press, 2014

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-0-7456-8325-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

CONTENTS

Manifesto

A Movement of Free Women: Preface by Galia Ackerman

Part I: The Gang of Four

1. Inna, a Quiet Hooligan

2. Anna, the Instigator

3. Sasha, the Shy One

4. Oksana, the Iconoclast

Part II: Action

5. ‘Ukraine Is Not a Brothel’

6. No More Nice Quiet Protests

7. Femen Goes All Out

8. In Belarus: A Dramatic Experience

9. Femen Gets Radical

10. ‘I’m Stealing Putin’s Vote!’

11. Naked Rather Than in a Niqab!

12. Femen France

13. Our Dreams, Our Ideals, Our Men

One Year Later: Afterword by Galia Ackerman

Notes

PLATES

The 42nd annual meeting of the World Economic Forum Davos 2012

All photographs are the property of the Femen association, except for: page 2, top right © Alessandro Serranò/Demotix/Corbis; page 5, top © Tatyana Zenkovich/epa/Corbis; page 6, bottom © Jean-Christophe Bott/epa/Corbis; page 8, © Sergey Dolzhenko/epa/Corbis.

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE BODY, THE SENSATION THE WOMAN HAS OF HER OWN BODY, THE JOY OF ITS LIGHTNESS AND FREEDOM. THEN CAME INJUSTICE, SO HARSH THAT IT IS FELT WITH THE BODY; INJUSTICE DEPRIVES THE BODY OF ITS MOBILITY, PARALYSES ITS MOVEMENTS, AND SOON YOU ARE HOSTAGE TO THAT INJUSTICE. THEN YOU PUSH YOUR BODY INTO BATTLE AGAINST INJUSTICE, MOBILIZING EACH CELL FOR THE WAR AGAINST THE WORLD OF PATRIARCHY AND HUMILIATION. YOU SAY TO THE WORLD:

OUR GOD IS WOMAN!

OUR MISSION IS PROTEST!

OUR WEAPONS ARE BARE BREASTS!

HERE FEMEN IS BORN, AND HERE BEGINS SEXTREMISM.

FEMEN

Femen is an international movement of bold, topless activists whose bodies are covered with slogans and whose heads are crowned with flowers.

The activists of Femen are women who are specially trained, physically and psychologically, ready to perform humanist tasks of every degree of complexity and provocation. The activists of Femen are ready to face repression, and their motivation is exclusively ideological. Femen: the crack troops of feminism, its fighting vanguard, a modern incarnation of the Amazons, fearless and free.

OUR IDEOLOGY

We live in a world under the economic, cultural and ideological occupation of men. In this world, woman is a slave deprived of any right to ownership and, in particular, any right of ownership over her own body. All the functions of the female body are subjected to strict control and regulation by patriarchy.

A woman’s body has become separated from her, becoming the object of monstrous patriarchal exploitation. Total control over the female body is the main instrument of woman’s oppression. Conversely, a female sexual tactic is the key to her liberation. Woman’s proclamation of her rights over her own body is the first and most important step towards her liberation. Female nudity, liberated from the patriarchal system, undermines that system. It is the manifesto of struggle and the sacred symbol of female liberation.

Femen’s naked-bodied attacks lie at the heart of the historical conflict between ‘woman’ and ‘the system’, and they are its most obvious and appropriate illustration. The naked body of an activist expresses unconcealed hatred for the patriarchal order and the new aesthetic of the feminine revolution.

OUR OBJECTIVE

Total victory over patriarchy.

OUR MISSIONS

• By the power of daring and personal example, to pass a comprehensive feminine sentence on patriarchy as a form of slavery.

• To provoke patriarchy into open conflict by forcing it to demonstrate its anti-human, aggressive essence so as to discredit it once and for all in the eyes of history.

• To ideologically undermine the fundamental institutions of patriarchy, dictatorship, the sex industry, and the Church, by submitting these institutions to diversionary tactics such as trolling, to obtain their complete moral capitulation.

• To make propaganda for the new revolutionary feminine sexuality, as opposed to patriarchal eroticism and pornography.

• To inject modern women with the culture of an active resistance to evil and the fight for justice.

• To create the community that is most influential and best able to fight in the world.

OUR DEMANDS

• The immediate political reversal of all dictatorial regimes that create intolerable living conditions for women; in the first place, the rule of theocratic Islamic states practising sharia and other forms of sadism vis-à-vis women.

• The total eradication of prostitution, the most brutal form of women’s exploitation, by criminalizing the clients, investors and organizers of this slave trade. The absolute and universal separation of Church and state, with a ban on any interference on the part of religious institutions in the civil, sexual and reproductive lives of modern women.

OUR TACTICS: SEXTREMISM

Sextremism is the main new form of feminist activism developed by Femen.

Sextremism is female sexuality that has risen up against patriarchy by embodying itself in extreme political acts of direct action. The sexist style of these actions* is a way of destroying the patriarchal idea of the predestination of female sexuality, in favour of its great revolutionary mission. The extreme nature of sextremism is a manifestation of the superiority of Femen activists over the vicious dogs of patriarchy. The form of unauthorized sextremist actions expresses woman’s historical right to protest in any place and at any time, without coordinating her actions with the patriarchal structures that maintain order.

Sextremism is a non-violent but highly aggressive form of activism; it is a super-powerful, demoralizing weapon that undermines the foundations of a corrupt patriarchal culture.

OUR SYMBOLS

The crown of flowers is a symbol of femininity and proud disobedience. It is the crown of heroism.

The body-as-poster is a truth expressed by the body with the help of nudity and the signs drawn upon it.

The Femen logo is the Cyrillic letter Ф (F), which mimics the shape of the female breasts, the main symbol of the women’s movement Femen.

Femen’s motto: my body is my weapon!

OUR STRUCTURE AND ACTIVITY

The international movement Femen carries out activities on the territory of democratic countries and reserves the right to act on the territories controlled by dictatorial regimes. Femen is registered as an international organization, and is currently establishing national Femen groups throughout the world. It seeks to expand the geography of its activity by attracting new activists. The preparation of sextremists is carried out in several training centres such as in France. The movement is led by a coordinating council which includes the founding members of the movement and its most experienced activists.

OUR FINANCING

To ensure the activities of our organization, Femen accepts donations from people who share its ideas and methods of combat. Femen also sells clothing and accessories with its symbols, and art objects of its own making. The movement is not dependent on any investor and refuses on principle to accept any financial assistance from political parties, religious organizations, or other lobbyists.

All the funds earned and collected serve the goals of the movement.

The only source of distribution of Femen’s production is the site: <http://www.femenshop.com>.

INFORMATION

Femen professes the principle of openness to the media, to ensure maximum media coverage of its revolutionary activity in defence of women’s rights.

At the same time, the movement is involved in a campaign for information and aggressive propaganda on the Internet, using the Web to transmit its ideology. Femen is present on all major social networks and communities on the Net.

The official sources of information on the activities of the Femen movement are the website <http://www.femenshop.com> and the Facebook page <http://www.facebook.com/Femen.ua>.

Femen, Kiev, January 2013

* The French word ‘action’ is here used both in the sense of a ‘direct action’ and a ‘demonstration’ of an artistic-political kind. It has links with what in the English-speaking world are (or were) often known as ‘happenings’ or ‘performance art’, and – as the Femen themselves point out – with the politico-aesthetic movement known as ‘actionism’. (Trans. note.)

A MOVEMENT OF FREE WOMEN

Preface by Galia Ackerman

At the age of fourteen or fifteen, these girls started to get bored. Their friends spent their time drinking beer out in the street and chatting or taking drugs, but none of these four young Ukrainian girls were really into any of this. In their poor backwoods towns, Anna Hutsol, Inna Shevchenko, Oksana Shachko and Sasha Shevchenko were looking for a meaning to their lives. With the help of a few Soviet books, they fantasized about the days when communist youth built up the country. That was before their time. Only Anna, a little older than the other three, could remember her early Soviet days, a happy childhood which for her has the taste of tangerines and chocolate.

Although they had heard of Stalin’s crimes, as far as they were concerned this was all in the distant past, while in the last years of the USSR, their parents lived peaceful lives and felt useful and respectable. Of course, reality was more complex and much less rosy, and concealed profound inequalities. But for them, nothing could be compared to the toxic atmosphere of the 1990s or the 2000s. The girls felt hatred for the wild west-style capitalism that allowed a happy few to get rich quickly and scandalously, and that laid waste the lives of ordinary people, including their families.

Against this backdrop of a loathing for capitalism in its post-Soviet guise, Sasha, Oksana and Anna discovered a circle of Marxist-influenced people holding street discussions in their hometown, Khmelnytskyi, in western Ukraine. A group of young people met regularly to study Soviet philosophy textbooks found in attics, as well as the works of Marx, Engels and the nineteenth-century German socialist August Bebel.

These young people were opposed to the current political and moral consensus.

During perestroika and in the early post-Soviet years, it was customary – in Russia as in Ukraine – to denigrate the Soviet period.

In Ukraine, national grievances had been superimposed on this discourse: the Soviet regime was accused of political and cultural imperialism, as well as crimes against the Ukrainian nation. President Yushchenko demanded that the UN recognize the artificial famine of 1932–3, which killed nearly 6 million people in Ukraine, as genocide.

And so, if we stick to the economy, both in Russia and Ukraine, official propaganda presented this liberalism – a liberalism that amounted to the plundering of national wealth by a handful of oligarchs close to the government – in the same way as did the Harvard School: it was seen as the only viable alternative to the dark communist past. In reality, this interpretation mainly gave a fake legitimacy to grossly unequal regimes. The power of the propaganda machine was such that, apart from the communist parties – viewed as backward-looking vestiges from the past – voices advocating social justice were very rare.

In this atmosphere of liberal diktat, it required a certain intellectual audacity to claim kinship with Marxism in the same way as other radical factions, such as the current Left Front of Sergei Udaltsov in Russia. The street circle of Khmelnytskyi continued to evolve, and some of its members, including three of the future Femen, tried putting into practice the lessons learned, by founding an association for student aid.

Meanwhile, for an entire year, the girls studied Bebel’s Women and Socialism, which became their favourite book. It was a real revelation and they decided to dedicate themselves to fighting for the freedom of women. In Bebel, they found a ‘scientific basis’ for their spontaneous hatred of misogyny and capitalism, as well as of the religion that oppresses women, always and everywhere. Armed with this reading, Anna, Sasha and Oksana excluded their male friends from the association and created a new movement, New Ethics. Soon they moved to Kiev.

From spring 2008, their actions, which had initially been innocent and childish, involved dressing up and making a splash. They pondered. What should they protest against? How to find targets? During one of their brainstorming sessions, they found their first big topic: Ukraine is not a brothel. They rebelled against the sex industry that flourished in the country, under the aegis of the government, and against Westerners’ perceptions of Ukrainian women, those ‘Natashas’ ready to fall into the arms of a ‘Prince Charming’ for a pittance or the promise of a dolce vita abroad.

During this struggle, which involved dozens of actions, the movement became more structured and renamed itself ‘Femen’. In 2009, Inna, a student in Kiev who came from another provincial city, Kherson, joined the trio from Khmelnytskyi. These four were the backbone of the group. Gradually, Femen found its trademark: a young topless woman with a crown of flowers on her head. In this book, they explain in detail the meaning of this ‘outfit’ that makes them recognizable worldwide.

In 2009, power in Ukraine was still in the hands of the coalition that emerged after the Orange Revolution. This revolution was a disappointment for many Ukrainians because the government – partly hampered by the global crisis – turned out to be unable to improve the economic situation in the country and to fight corruption. At the end of 2009, the country was polarized on the eve of the presidential election. Viktor Yanukovych, defeated in 2005, faced both the outgoing president Viktor Yushchenko and Yulia Tymoshenko, the former muse of the revolution who in the meantime had become an opponent and rival to Yushchenko. As in the past, Yanukovych was supported by the Russian regime.

The Femen, who do not want to be limited to issues traditionally seen as ‘feminine’, decided to join in the political struggle. They took up a position that would give them a very negative press in the eyes of many Ukrainians, choosing to be neither for the ‘blue’ camp of Yanukovych, whom they considered as a puppet of the big oligarchic capitalists of east Ukraine, nor for the ‘orange’ camp (supporters of Yushchenko or Tymoshenko), because of their political and economic fiasco. They harboured a particular hatred for Tymoshenko, an elegant and charismatic woman who was prime minister from December 2007 to March 2010, because in their view she did nothing to combat the sex industry or to improve the status of women. However, once Yanukovych had assumed power, the situation soon became clear to the girls. Despite its flaws, the Orange Revolution had brought several freedoms, while the regime that took over was becoming increasingly repressive. From this period, Femen grew politically more radicalized. Their new enemy was dictatorship. The police, the judiciary and the SBU, the security service of Ukraine (an offspring of the Soviet KGB), kept them under surveillance. They experienced their first appearances in court, their first stays in jail and their first interrogations by SBU officials.

They realized that fighting for women’s rights in today’s Ukraine would be difficult and would involve rebelling against the police state. They also realized that Ukraine would never be free while Russia was governed by the ‘Putin system’, and they saw themselves as morally obliged to support the Russian opposition as it challenged the massive frauds perpetrated in the general elections of 2011. Femen undertook a series of spectacular actions both against the Yanukovych regime, in Kiev, and the Putin regime, in Moscow: they were held in Russian prisons.

What is extraordinary in Femen, and makes them very special in the post-Soviet arena, is their openness to the outside world. These girls respond to the status of women or the drift towards dictatorship in Ukraine, but they also show their solidarity with the democratic struggle of others. After their protests against the Putin regime – protests that were not actually much to the liking of the Russian opposition movement, which is too inward-looking and unappreciative of the boldness of these ‘little Ukrainian girls’ – they decided to attack the regime of Alexander Lukashenko, the Belarusian president who is considered to be the last dictator in Europe. Their Belarusian tour in December 2011, where they fell into an ambush laid by the sinister local KGB, was probably their most terrible experience. It could have ended in real tragedy. In two or three years, the girls had become seasoned fighters who, with their naked bodies covered with caustic slogans, were defying police officers armed with batons.

Quickly, they embarked on a new battle. As atheists since their teens, they have fully assimilated Marx’s famous phrase, ‘religion is the opium of the people’. For them, religion is a tool for patriarchy to dominate women. The Femen therefore decided to launch an attack on clericalism, whether Islamic or Christian, because it is always women who suffer from it. After protesting in 2010 against the Iranian judicial decision to stone Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani to death, they gave a major role to anti-clerical struggle in their actions, from 2011 onwards. They were protesting in the Vatican and Kiev, in Moscow and Istanbul, in Paris and London.

We need to understand how much the Femen are going against the grain in Russia and Ukraine. In these countries, the Orthodox Church, which was persecuted in the Soviet period, has risen from the ashes but is gradually placing itself at the service of the state, to the point where it has become the de facto state religion in Russia. The Femen denounce its reactionary and outdated teachings, and its collusion with corrupt regimes. They denounce it even more violently than do the women of Pussy Riot. With the same energy and determination, they address the medieval practices of countries where sharia law prevails. They are not afraid of brushing against the spirit of tolerance of our Western soci-eties: they call a spade a spade. In their view, for example, Europe must refuse to accept the wearing of the niqab or burqa. ‘Muslim woman, get undressed!’ – this is the slogan that best summarizes the appeal made by Femen to the Muslim women of the world, and especially those who live in the Western world.

Thanks to their anti-clericalism, the ideology of Femen can take on sharper edges. They are carrying out spectacular and more dangerous actions against what they see as the three manifestations of patriarchy: the sex industry, dictatorship and clericalism. Added to this are, of course, their purely anti-capitalist demands such as their actions at the World Economic Forum in Davos. According to Femen, women are the first victims of the poverty imposed by the masters of the world.

The European media, but also the media of many other countries, eagerly cover the actions of Femen. It’s as much the form as the content that attracts them. Each time, they can watch a mini-drama where the spectator’s interest is aroused by the danger faced by the women taking part. Reports on Femen rarely explain their doctrine, but abound in spectacular photos. And of course, these young women are the food and drink of directors of documentaries.

How could it be otherwise? These girls sound the alarm on the bell tower of the cathedral of Kiev, climb the walls of the enclosure at Davos under the noses of snipers positioned on the roof, protest topless outside the largest mosque in Istanbul and attack the Catholic fundamentalists of Civitas disguised as ‘naughty’ nuns, wearing the inscription ‘In Gay We Trust’ on their chests. And snapshots of them fighting with the cops or security services are all part of the ‘show’. We are confronted with a new phenomenon: the Femen use the means of an increasingly radical artistic actionism for purely political reasons, while deliberately refusing to recognize themselves as artists. This is the price these bold women pay, in full awareness, for the dissemination of their ideas.

In autumn 2012, the Femen moved to France, while maintaining their office in Kiev. It was at this time that I made their acquaintance. I met Inna, then the other three founders, Oksana, Sasha and Anna, passing through Paris. I built up this book from dozens and dozens of hours of interviews with them. These are their words. Why did I want to write this book for them?

As a journalist and expert on Russia and the post-Soviet world, I had for several years been interested in the phenomenon of young radicals who preach Marxism and socialism, despite the disaster represented by the Soviet experience. The way I imagined Femen – as young idealist girls rebelling against untamed capitalism in its oligarchic version – was largely confirmed upon my first contact with them.

But I discovered much more than this: four young women of extraordinary courage, creative and modern and, above all, full of compassion for the women in distress around the world. And because they feel a genuine compassion, they are also capable of a fierce hatred for those who cause suffering. In this, they are of the same metal as the great revolutionaries. The Femen seem to me to be the heirs of the long line of rebellious women from the Tsarist era, such as Vera Zasulich, Vera Figner, Catherine Breshkovsky, Alexandra Kollontai, and many others. But of course, in the age of the Internet and of show business, their passion can lead to very different results. Instead of drifting into terrorism, the Femen, radical at heart, have found a method of tackling their enemies that is both fun and highly symbolic: they use the naked body instead of a gun or a bomb.

So why did I decide to help them tell their stories? Despite a number of ideological differences (I’m not a Marxist and I’m agnostic rather than atheist), I feel close to their struggle. I can only share their revolt against the sex industry, which is an abomination. But it is especially their fight against dictatorship that inspires me with the greatest sympathy. In Soviet times, I systematically supported dissidents and, nowadays, the democrats who oppose Putin’s regime and other autocratic regimes in the post-Soviet world. I was and remain a close friend of some key figures of dissent and opposition in Russian politics, such as Anna Politkovskaya, Elena Bonner, Alexander Ginzburg, Vladimir Bukovsky and Sergei Kovalev, just to name a few, even if some are unfortunately no longer among the living. And I maintain my friendship with a great Ukrainian dissident who lives in France, Leonid Plyushch.

That leaves their anti-clericalism. The Femen are convinced atheists who believe that all religion oppresses women. This is historically true, but different religions have not evolved in the same way. Protestants and liberal Jews have come a long way in giving women an equal place to men. The Catholic Church, once the Church of the Crusades and the bonfires of the Inquisition, is also changing slowly but surely. However, the Russian Orthodox Church, faithful to its Byzantine and Tsarist traditions, has become the pillar of the Putin regime. This government, which for years has crushed political opposition and the free press, and which finally lost its legitimacy in the last general election marred by massive fraud, relies more than ever on the Church which, for its part, is taking this opportunity to extend its influence, including in Ukraine. Should we tolerate this collusion between the Putin government and the patriarchal Church, some of whose hierarchs have emerged from the KGB? For me, the answer is no. Without sharing their militant atheism or supporting some of their actions, their denunciation of the positions of the Orthodox Church seems justified.

Far beyond their glamorous political activities, the adventures of these four young Ukrainian women are well worth being known and understood.

These ardent girls, who advocate resolutely European values, are a symbol of hope for our old continent, even if we do not always agree with their ideas or methods. It is as if it were from an all too often disregarded Eastern Europe that the vanguard of bright, bold forces were disembarking. What will the future of Femen be? Their Paris training centre, open to activists from around the world, is there to train the ‘soldiers’ of feminism, so as to attack the oppressors of women and to allow women to be free and fulfilled. Is this the beginning of a global feminist revolution, something for which Femen yearn? We can only hope so.

Part I

THE GANG OF FOUR

We’re sometimes called the ‘gang of four’. ‘We’ are Inna Shevchenko, Sasha Shevchenko (it’s a very common name in Ukraine, we’re not related), Oksana Shachko and Anna Hutsol. And ever since we formed the core of Femen, we’ve been inseparable. Three of us, Anna, Oksana and Sasha, are from the same town in western Ukraine, Khmelnytskyi. There we started to study philosophy and to be politically active, before arriving in Kiev. As for Inna, she comes from the town of Kherson, near Odessa, and she joined the other three founding members of Femen in Kiev, to become the fourth ‘pillar’.

What was life like for each of us before Femen? In what families did we grow up? Why did we feel the need to fight for women’s rights? How did we become atheists in a post-communist Ukraine where religion is taking over in ever more important areas?

1

INNA, A QUIET HOOLIGAN

I was born in a ‘godforsaken hole’ in southern Ukraine, in other words in a small provincial town, Kherson. They speak Russian there, like in Odessa, which isn’t very far away. It’s still a very Soviet town, where the USSR still seems to be in existence and nothing ever changes. It was in this quiet town, that’s infuriated me ever since my childhood, that I very soon started to tell myself I’d make a life for myself elsewhere.

When I was a little girl my only friends were boys, and I loved climbing trees. I dressed in shorts and sneakers; I hated dresses. This made Mom furious: she really didn’t like the fact I wasn’t like a model little girl. I didn’t even refuse to wear dresses, but Mom just knew I’d immediately get them dirty and tear them, either by climbing an oak tree or playing with stones on a construction site. Near our apartment block, there was one such site and in the evening, when the workers left, our little gang invaded it and built castles out of the bricks. I needed freedom, and instead of playing with dolls or messing about in a sandbox, I preferred to join the boys on more out-of-the-way expeditions. I didn’t want to be a boy, but I liked having them round me. I was a kind of quiet hooligan, who never took part in fights. The only person I quarrelled with from time to time was my older sister.

Apart from that, I was a well-behaved child. My parents never gave me a spanking. In fact, I’m lucky to have a very nice family. I’d define my mother as an ‘ideal woman’ for Ukraine. She was a chef in a restaurant before becoming chef in a university cafeteria. She’s a typical Ukrainian woman who works full time but also keeps her house spotless, cooks, and takes care of her husband and children without losing her temper or, more precisely, without ever showing her emotions – a nice, quiet, positive and very pleasant woman. But she’s not a fulfilled woman, even if she doesn’t complain about anything. She bears her fate, like a donkey carries its load, without realizing she could have had a different life. I suffered for her. In those days, I didn’t know the word ‘feminism’, but I thought this life was unfair. And the fact it was the norm was no consolation to me. I realized early on that I never would live like her. On the other hand, my sister, who’s five years older than me, completely internalized this model. In fact, she married at nineteen, had a child at twenty-one, and lives and works in Kherson. However, we’ve remained very close, and she’s always supported me.

Dad is a very emotional man, sometimes short-tempered, but he has a good heart too. In the family, we never had any real arguments. With his sense of humour, my father’s always turned any conflict into a mere joke. Our parents argued with my sister and me, without it ever turning nasty.

Dad’s a retired soldier, a former major in the troops of the Ministry of the Interior. I’ll never be able to imagine him without his uniform. During our childhood, when our parents went out, my sister and I would take turns to dress up in Dad’s uniform, but we never had any desire to try on Mom’s dresses or high heels. And when he got promoted, we’d make a hole in his epaulette to screw in a new star. For us, it was a sacred ritual!

If I got good grades in school and worked hard, this was also thanks to my father. He always talked to me as if I was a grown-up and kept telling me I was studying for myself, for my future. When I started at primary school, he told me that my adult life was about to begin. I quickly realized that there was a hierarchy at school: some children are better liked by the teachers, who straightaway help them and stimulate them. It’s a virtuous circle: if you work hard, you’re appreciated by the teachers, and they push you to develop your abilities and become even better. From the first year, I wanted to be the class representative. And I conducted the first electoral campaign of my life. I was elected by a show of hands. In fact, the role gave me a serious responsibility because it meant keeping a register of late arrivals and absences, organizing and lining up the pupils for outings and so on. I held this position throughout my time at school, up until my final exams.

Around the age of twelve, I went through a bit of a crisis. I suddenly realized that the boys preferred girls with dresses and pretty little shoes. As I wanted to be first in everything, I started to dress in a more feminine way and I grew my hair down to my waist. The effect was instantaneous: a lot of boys fell in love with me, including some of my friends. There were plenty of girls who wanted to be my friend because I was the leader of the class, but I thought they were airheaded chatterboxes and I kept my distance. I’d just one girlfriend who was also an excellent pupil. We shared the same table and with her I felt comfortable. In my class, out of twenty-two pupils, there were only seven boys. With my one girlfriend and these boys, we formed a separate group, away from the other girls.

When I was about fourteen, I developed a new ambition: I got it into my head that I’d become president of the school. For us, this was an important function, much more than being just class representative. The school president attends school board meetings and voices the wishes and grievances of the pupils. He or she also organizes competitions and festivals – an important personage, in short. And then the title itself is rather flashy: president! In theory, you can take on this post when you’re in the fifth year of secondary school but, in general, pupils vote for people who are in their final year. So my chances of being elected in the fifth year were almost zero. Still, I decided to stand against the nine other candidates. We campaigned for three weeks. We handed out leaflets and each made two public presentations of our platforms. These presentations took place in the main hall where candidates had to go on stage and try to convince the audience. Almost all the pupils took part in the elections, we all wanted to play at democracy, that game for adults. In each class there were ballot papers and boxes. The count was conducted by teachers and pupils drawn by lot.

The day after the election, our class was on duty to maintain order in the school. As class representative, I had specific obligations: I had to place pupils at monitoring stations in the canteen, the schoolyard and so on. Just then, the headmistress ran up and whispered in my ear that I’d won. It turned out that I’d won the majority of votes in thirteen classes out of fifteen – it was an outright victory! That was how my career as president started, and I was re-elected twice, in the last two years at school. This was my first ‘political’ experience, an unforgettable one, the start of which coincided with the 2004 presidential campaign.

The two main presidential candidates in Ukraine were Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych, who was backed by the outgoing President, Leonid Kuchma. Back in Kherson, everyone supported Yanukovych, both my family at home and the teachers at school. And then pressure was put on us too. For example, Mom told us that, at her workplace, officials in the local government had threatened to fire anyone who voted for Yushchenko. I tried to explain to my mother that this was bollocks, but she was scared. In eastern Ukraine, most people were aware that Yanukovych wasn’t a good candidate, but, out of fear of retaliation or indifference, many were ready to vote for him in spite of everything.

I remember propagandists from the Donbas, the stronghold of Yanukovych, claiming, ‘He’s a local lad, he went to prison, like so many other people, for snatching hats.’1 This kind of activity is usually carried out by small-time thugs who snatch the hats off people’s heads and only give them back if they’re given a few coins in exchange. That said, metaphorically speaking, this is how the majority of Ukrainians live – committing petty crimes to survive when they’re living in poverty. So it was a clever propaganda technique to present Yanukovych as a man of the people challenging the intellectual Yushchenko, the candidate of the Ukrainian-speaking elite and married to an American. The Yushchenko couple also spoke Ukrainian at home, and their children wore traditional costumes, shirts with embroidered collars, which was both incredible and intolerable for people in eastern and southern Ukraine. Indeed, the Soviet propaganda that supported Yanukovych presented Ukrainian nationalism as a kind of backwardness. To have a career, you absolutely had to be Russian-speaking.