Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

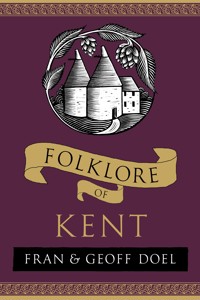

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Folklore

- Sprache: Englisch

Kentish folklore reflects the curious geography and administrative history of Kent, with its extensive coastline and strong regional differences, which are reflected in distinctive cultural traditions. Bounded by sea on three sides, Kent has the longest coastline of any English county and was the base for much maritime activity, giving rise to communities rich in sea-lore. Fran and Geoff Doel explore the folklore, legends, customs and songs of Kent and the causative factors behind them. From saints to smugglers, hop-pickers to hoodeners, mummers to May garlands and wife sales to witchcraft, this book charts the traditional culture of a populous and culturally significant southern county.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 268

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedication: for Ken Thompson (1919-2001) Man of Kent and Kentish Man

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Introduction

1 Spring & Summer Customs

2 Autumn & Winter Customs

3 Smuggling & Lore of the Sea

4 Hopping Down in Kent

5 Things Holy Healing Saints, Holy Wells & Hermits

6 Pageants & Street Theatre

7 Things Unholy Superstition & Witchcraft

8 Legends & Ghost Lore

9 Anti-Social Customs

10 A Question of Charity?

11 The Songs of the People

Notes & Acknowledgements

Appendix

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

‘Kent, sir – everybody knows Kent – apples, cherries, hops and women’, Mr Jingle says memorably in Charles Dickens’ Pickwick Papers, a novel with a partly Kentish setting where Maidstone features as ‘Muggletown’ and Cob Tree Manor as ‘Dingley Dell’. The Pickwickians and their host Mr Wardle like their food and a ‘Kentish stomach’ is traditionally a strong one. The Elizabethan poet Edmund Spenser also comments favourably on the women – ‘Lythe as Lass of Kent’ – and the traditional culture of fruit growing and hop picking is celebrated. What does Mr Jingle omit? Well, the plethora of Kent’s indigenous saints and its former greatness as the most famous pilgrimage centre in Britain; the richness of its folk drama and rituals; and its maritime heritage of fishing, trade and smuggling to name but a few.

Kent is bounded on three sides by sea and has the longest coastline of any English county which, according to Parish and Shaw’s Dictionary of the Kentish Dialect, contributed to the growth of a highly individualistic culture and in-breeding – hence the derogatory phrase ‘Kentish Cousins’:

This county being two-thirds of it bounded by the sea and the river, the inhabitants thereof are kept at home more than they are in inland counties. This confinement naturally produces intermarriages amongst themselves.

Far from being insular, the maritime communities of Kent used the sea and rivers as mediums of travel and the Kentish ports thrived, not just as fishing communities rich in sea-produce (and sea-lore), but as trading centres with considerable traffic in people and goods and of significance in war as well as peace since Kent was usually the prime target for planned invasions. The Cinque Ports (four of which – Sandwich, Dover, New Romney and Hythe – are in Kent) had the responsibility under various charters of providing either fighting vessels or transports in times of war from late Anglo-Saxon times to the seventeenth century. This could be up to fifty-two ships for fourteen days in any one year in return for extensive privileges. Beyond the specified number of ships and days, an agreed payment was made.

These privileges included ‘Den and Strond’ – the right to haul boats onto the shore and to dry nets on the strand or beach – and exemption or reduction of certain import and export duties. The post of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (usually combined with the office of Constable of Dover Castle) was created to safeguard the rights of these ports and to reflect their influence in government circles. Remaining privileges today include holding Courts of Brotherhood and Guestling once a year and rights of attendance at coronations.

Since medieval times Sandwich has had a Mayor Deputy in each of its ‘limbs’ who send representatives annually for the ceremony of Confirmation of Deputies. For the privilege of links with Sandwich and its Cinque Port status, the towns are levied annual ‘Ship Money’ – 10s from Brightlingsea; 3s 4d from Fordwich; and 1s 8d from Sarre, which for many years has pleaded inability to pay at the ceremony for diverse ingenious reasons!

Proverbially Kentish miles were extra long, perhaps because of the vast breadth of the county (which seems to have been originally two distinct kingdoms and administrative areas surviving as East and West Kent, each with its bishopric) that gave rise to the proverb ‘Essex stiles, Kentish miles, Norfolk wiles, many men beguiles’. Early division may have a bearing over the long controversy about the distinction between ‘Men of Kent’ and ‘Kentish Men’, neatly summed up by Alan Major in his A New Dictionary of Kent Dialect:

Formerly ‘A Man of Kent’ was a man born between the Kentish Stour and the sea, all others being ‘Kentish Men’. Another version said that a ‘Kentish Man’ was one born in Kent, but not of Kentish parents, while a ‘Man of Kent’ was one whose parents and ancestors were Kentish. A more common version is that a ‘Man of Kent’ is one born east of the river Medway, while a ‘Kentish Man’ is one born west of the Medway.

Despite these apparent differences between East and West Kent, and affinities between West Kent and East Sussex (particularly with regard to folk songs and customs and smuggling and hop-picking traditions) there are distinctive features in Kent folklore, perhaps partly due to insularity caused by the bad roads through the rich and fertile Wealden clay, which gave rise to the proverb ‘Bad for the Rider, Good for the Abider!’

Kent has always been important and wealthy; Julius Caesar commented on how civilised the Britons were in the south-east and the wealth of Kent is cited in early proverbs:

A Gentleman of Wales, with a Knight of Cales*

And a Lord of the North Countrie,

A Yeoman of Kent upon a rack’s Rent

Will buy them out all three.

*A knight made by the Earl of Essex on his Cadiz expedition (1596)

Another proverb connects wealth and poverty to healthy and less healthy terrain in Kent:

Rye, Romney and Hythe,for wealth without health;

The Downs for health with poverty;

But you shall find both health and wealth

From Foreland Heath to Knole and Lee.

The first line refers to the area of Romney Marshe, the ‘sixth continent’, infamous for ‘Kentish Ague’, a kind of marsh fever. The marsh is one of several distinctive areas of Kent with their own economic, social and cultural traditions and terminology (such as the ‘Romney Looker’ meaning a shepherd). The Isle of Thanet is another and perhaps also are those former parts of Kent now sadly captured by Greater London (but which we shall nevertheless include in this book).

William Lambarde writes in his Perambulation of Kent that:

The yeomanrie, or common people… is no where more free, and jolly, than in this shyre: for besides that they themselves say in a clayme (made by them in the time of king Edwarde the First) that the communaltie of Kent was never vanquished by the Conqueror, but yeelded itself by composition.

Lambarde and other early chroniclers cite the traditional story that by their threatened armed resistance the people of Kent persuaded William the Conqueror to allow them to continue with their ancient customs, one of which was inheritance under the Gavelkind system, which legally remained as the Common law of Kent until the twentieth century. Lambarde says that:

Copyhold tenure is rare in Kent, and tenant right not heard of at all. But in place of these, the custome of Gavelkind prevailing every where every man is a freeholder, and hath some part of his own to live upon.

Alan Major defines Gavelkind as:

An ancient Saxon custom distributing an equal division of the lands of the parent among his sons or children. From the Anglo-Saxon gafol, a tribute, although it has been suggested gavelkind is a corruption of the German gieb alle kind (give all to the children).

As Percy Maylam pointed out in his detailed pamphlet on the subject in 1913, Gavelkind remained the usual system of inheritance throughout the kingdom until at least the reign of Henry III, so we need to look for another reason for its long survival in Kent; Percy Maylam suggests this might be ‘The small number of tenures in Kent held by knight service’, that is military service as opposed to the ‘non-military tenure of ‘free scotage’ or agricultural or monetary services.’

One of the advantages of Gavelkind was that if the father was executed for treason or other crimes, only his goods and chattels but not his land were forfeit to the crown, hence the Kent proverb:

The Father to the Bough, [the gallows]

And the son to the Plough

Earlier versions of this had ‘logh’ (meaning ‘place’) instead of ‘plough’. Another distinct feature of Gavelkind rehearsed in a Kentish proverb was that the widow of a tenant was allowed to keep the estate if they were childless or their children under age. If any of the children were of age, the widow kept half the estate during her lifetime. The relevant proverb, found in its earliest form in the Queenborough Statute Book, runs: ‘Si that is wedewe, si is levedi (She that is a widow, she is the lady).

Kent has had its fair share of political, religious and socio-economic rebellions and disturbances, with their own rich folklore and proverbial terms and sayings. ‘Kentish Fire’ for example was a term given to the continuous cheering common to the Protestant meetings held in Kent in 1828 and 1829 opposing the Catholic Relief Bill. The following proverb is a pithy reference to the social injustice of enclosures:

It is a fault in man or woman

To steal a goose from off a common.

But it admits of less excuse

To steal a common from a goose.

Kent’s rich folklore has been inseparable from its traditional culture – its economic, social and religious way of life – which has included saints and smugglers, hoodeners and hop-pickers. Evolving patterns of life still affect living and developing folklore; for example for people standing in the middle of West Malling: ‘If you can hear a train it’s going to rain’. Will Kent folklore and customs ever cease to fascinate patriots and friends of this remarkable and historic county? ‘It won’t happen till the moon comes down in Calverley Road’ as they say of impossibilities in Tunbridge Wells!

1

SPRING & SUMMER CUSTOMS

Traditionally, spring begins on St Valentine’s Day (14 February) when the birds mate – ‘the Birds’ Wedding Day’ as it was called in neighbouring Sussex. Geoffrey Chaucer, a poet with strong Kent connections, uses this tradition in his dream-vision poem ‘The Parliament of Fowls’ from around 1382:

For this was on seynt Valentynes day,

Whan every foul cometh there to chese his make,

Of every kynde that men thynke may

That sexual pairing on this day extended to human beings, at least symbolically and traditionally, is shown by the final verse of the folksong ‘Dame Durden’, found extensively in the south of England including Kent and Sussex:

Twas on the morn of Valentine

When birds began to prate,

Dame Durden and her maids and men

They altogether mate

Chorus

Twas Moll and Bet and Doll and Kit

And Dorothy Draggletail;

It was Tom and Dick and Joe and Jack

And Humphrey with his flail.

Then Tom kissed Molly

And Dick kissed Betty

And Joe kissed Dolly

And Jack kissed Kitty

And Humphrey with his flail

And Kitty she was a charming girl

To carry the milking pail

In Sussex the Copper family version bowdlerises the sexual word ‘mate’ to ‘meet’.

In the seventeenth century there was a custom (operating among the middle classes at least) that the first man to greet a lady on St Valentine’s Day would be her Valentine; husbands apparently didn’t count! This involved the man buying the lady a present, such as a pair of gloves and some harmless social contact later in the day (such as sitting next to each other at a Valentine’s Day feast); probably a kiss was also permitted. That the lady had to ‘accept’ the first comer, and therefore contrived to ensure the man was acceptable, is shown by the reference in Samuel Pepys’ Diary for St Valentine’s Day 1662:

Valentine’s day. I did this day purposely shun to be seen at Sir W. Battens – because I would not have his daughter to be my Valentine, as she was the last year, there being no great friendship between us now as formerly. This morning in comes W. Bowyer, who was my wife’s Valentine, she having (at which I made good sport to myself) held her hands all the morning, that she might not see the paynters that were at work in gilding my chimney-piece and pictures in my dining-room.

Originally gifts were sent to one’s Valentine; there are records of this happening in Roman society at this time of year and the festival, named after an early Christian martyr, may have absorbed features of some earlier celebration or ritual connected with springtime courtship. Love notes and cards became popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Shakespeare has a hero called Valentine who serenades his love outside her bedroom window in The Two Gentlemen of Verona and in East Anglia there are records of children singing love songs outside houses on Valentine’s Morn to collect pennies, which might be the remnants of an adult custom.

Shrovetide

Shrovetide is a moveable spring festival; the name derives from two Anglo-Saxon words meaning ‘the time to be shriven’ – to confess one’s sins before the forty-day Lenten fast during which the consuming of meat, milk, eggs, butter and cheese were forbidden on weekdays. The ‘shriving bell’ (later known as the ‘pancake bell’ at Maidstone) summoned people to church in pre-Reformation days. After the service and shrivings there was the consumption of food forbidden in Lent incorporated into traditional pancakes to be used up and then the playing of rough sports such as street football and cock-fighting which were also frowned upon in Lent. The pancakes and violent sports survived the Reformation and there is a reference to the ringing of the pancake bell in Maidstone to encourage the wives to begin the repast. Taylor’s ‘Jack-a-Lent’ (1630) includes a recipe:

There is a thing called wheaten flowre, which the cookes doe mingle with water, eggs, spice and other tragicall, magicall inchantments, and they put it by little into a frying pan of boyling suet where it makes a confused dismall hissing (like the Learnean snakes in the reeds of Acheron, Stix, or Phlegeton), untill, at last by the skill of the Cooke, it is transformed into the forme of a Flap-jack, cal’d a pancake, which ominous incantation the ignorant people doe devoure very greedily.

At Olney in Buckinghamshire there is a famous Shrove Tuesday Pancake Race for the housewives, who toss pancakes in saucepans as they race, which has recently been copied by a local ladies’ society in Tunbridge Wells. Shrovetide afternoon continued as a half-day holiday for schools into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with the tradition of ‘barring out’ the teacher, who was only admitted to the classroom on condition that he or she agreed to a half day holiday. Consequently all sorts of strange customs and sports are recorded on Shrove Tuesday afternoon such as this one, reported to the Gentleman’s Magazine ‘as occurring in an unspecified East Kent village’ in 1779:

I found an odd sort of sport going forward: the girls, from 18 to 5 or 6 years old, were assembled in a crowd, and burning an uncouth effigy, which they called an Holly-Boy, and which it seems they had stolen from the boys, who, in another part of the village, were assembled together, and burning what they called an Ivy-Girl, which they had stolen from the girls; all this ceremony was accompanied with loud huzzah, noise and acclamations. What it all means I cannot tell, although I inquired of several of the oldest people in the place, who could only answer that it had always been a sport at this season of the year.

Easter

Because of the significance of the Last Supper and the Maundy traditions (based on Christ’s commands to his disciples to assist the poor), Easter was a favourite time for bequests giving annual doles to the poor. Kent’s most famous Easter tradition, the Biddenden Dole, is covered in chapter 10. Egg rolling derives traditionally from north-west England, but in Tunbridge Wells eggs have been rolled on Easter Monday in the Calverley Gardens since the 1970s.

May Garlands

The first of May celebrates the beginning of summer in the traditional calendar with maypoles, may garlands and Jack-in-the-Greens. May Day was an unofficial bank holiday for many years and in the morning children used to carry May garlands from door to door, sometimes with a doll therein representing the May Queen, singing a song which included requests for the customary tribute and inappropriate religious reminders of man’s mortality. The Whitstable May Song is typical in this bizarre mixture of celebration, begging and gnomic religious reflection:

The first of May is garland day, we wish you a merry May,

We hope you like our May garland because it is May day.

A branch of May we have brought you and at your door we stand,

It is but a sprought, but well budded out by the work of our poor hands.

This morning is the first of May, the primest of the year,

So people all both great and small, we wish you a joyful year.

We have been wandering all the night and almost all this day

And now returning back again, we’ve brought you in the May.

I have a purse upon my arm and drawn with a silken string.

It only wants a few more pence to line it well within.

Come give us a cup of your sweet cream, or a jug of your fine beer

And if we live to tarry the town, we’ll call another year.

The life of man is but a span, he’s cut down like the grass,

But here’s to the green leaf of the tree, as long as life shall last.

So why not do as we have done the very first day of May?

And from our parents we have come, to roam the woods so gay.

And now we bid you all adieu and wish you all good cheer,

We’ll call once more unto your house before another year.

God bless our Land with power and might, send peace by night and day.

God send us peace in England, and send us a joyful May.

In some areas in Kent, May Day was called Garland Day; the earliest reference we have to a procession carrying a May garland in Kent is in 1672, when one was ambushed by the press gang looking for recruits to fight the Dutch. Thomas Trowsdale wrote a detailed account of ‘Garland Day’ at Sevenoaks in 1880:

This morning I had the pleasure of witnessing a lingering remnant of the olden observances of “Merrie May-day”. Numbers of children went about from house to house in the Sevenoaks district in groups, each provided with tasteful little constructions which they called May-boughs and garlands. The former were small branches of fruit and other early blossoming trees secured to the end of short sticks, and were carried perpendicularly. One of these was borne by each of the children. Two in every group carried between them, suspended from a stick, the “May-garland”, formed of two transverse willow hoops, decorated with a profusion of primrose and other flowers, and fresh green foliage… At every door the children halted and sang their May-day carol, in expectation of a small pecuniary reward from the occupants of the house… Middle-aged matrons who have resided in this part of the ‘garden of England’ all their lives, speak in terms of pardonable pride of the immense garlands of their girlhood. Forty years ago, I am told, the May-garlands often exceeded a yard in diameter, and were constructed in a most elaborate manner.

Another account of nineteenth-century garlanding comes from Bearsted:

The custom of “garlanding” occupied the girls on May Day. They would dress a doll suitably for the occasion, and would then fix it to two garlanded hoops. The whole would be covered with a sheet, which was lifted for a small token to reveal the undoubted beauty of some of the creations of flowers.

A photo from around 1913 shows a May Day procession of infants at Hadlow School. A May Queen was chosen by votes by the children and was given a cross and chain by the wife of the vicar; other girls acted as attendants and dresses were kept at the school. The custom was recorded as late as 1933 and there was also Maypole Dancing.

The association of young girls with garlands has a sadder connotation in the widespread custom of ‘virgin’ or ‘maiden’s garlands’ hung in church at the funerals of young unmarried girls. Such a garland was noticed at Plaxtol Church in 1836 – ‘a garland and a pair of gloves cut in white paper hanging from the roof’. A letter to the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1747 from a Bromley correspondent records the discovery of a garland by the parish clerk who:

By his digging a grave in that church-yard, close to the east of the chancel wall, dug up one of these crowns, or garlands, which is most artificially wrought in filigree work with gold and silver wire, in resemblance of myrtle… whose leaves are fasten’d to hoops of larger wire of iron, now something corroded with rust, but both the gold and silver remains to this time very little different from its original splendour. It was also lined with cloth of silver.

Jack-in-the-Greens

Jack-in-the-Greens (men in wicker casings stuffed with evergreens) were sometimes known as the ‘chimney-sweepers garlands’, because the earliest accounts and drawings of them (from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries) associate them with that occupation. The earliest surviving references are from London, but in the mid-nineteenth century many chimney sweeping families migrated to towns in the south-east, taking the custom with them. The tradition is documented in a number of Kentish towns, such as Lewisham, Deptford, Greenwich, Bromley and Orpington, and has been revived at Whitstable and Rochester. There is an eye-witness account of the Lewisham Jack-in-the-Green in 1894:

May Day, 1894, at Lewisham. In the High Street, at the inn near St Mary’s Church, we saw a Jack with a Queen of the May, two maidens-proper, one man dressed as a woman, and a man with a piano-organ. The organ was playing a quick tune and the Queen and the maidens danced round the Jack with a kind of “barn-dance”, the Jack turning the other way. The man-woman sometimes danced with the maidens, turned wheels, and collected pence. The Jack was a bottle-shaped case covered with ivy leaves and surmounted by a crown of paper roses. The Queen wore a light-blue dress and had a crown similar to Jack’s. The senior maiden wore a red skirt and a black body; the junior wore a white dress; each wore a wreath of roses. The man-woman wore a holland dress and over it a short sleeveless jacket; his face was blackened, and had a Zulu hat trimmed with red, the brim being turned up.

The Whitstable tradition of the Jack-in-the-Green on May Day survived until about 1912; a photograph of about 1910 survives, when a procession of morris dancers accompanied the Jack from outside the Duke of Cumberland, Horsebridge, to the site of the maypole. The Whitstable tradition has been successfully revived and moved to the early May bank holiday.

The well-known Rochester historian Edwin Harris witnessed the custom in his youth, and wrote two accounts, the first in a pamphlet published in 1899:

The first of May, the Sweeps used to perambulate the City of Rochester and district with a “Jack-in-the-Green” and collect money for a carousal. Also on the same day children from the country would carry garlands from door to door, soliciting money, with the usual phrase of “Please remember the Garlands”.

In 1932, in one of a series of articles on Recollections of Rochester for the Chatham, Rochester and Gillingham Observer he gave a more substantial account:

There was a row of very old-fashioned cottages at the rear of the (Cock) tavern… The first of these cottages was inhabited by Mates, a sweep, from which circumstance it was sometimes called Sweep’s alley… I have on several occasions seen the sweeps making their “green castle” there for the May-day festival of Jack-in-the-Green.

The “green” would be about six feet high, smaller at the top than at the bottom, which allowed the Jack to walk. On a level with his face was a small square aperture to enable him to see where he was going, also, incidentally, to admit of a quart pewter pot to be passed to him. At many of the public houses a pot or pots of beer would be given, and of this Jack would have his share, and as he danced and rotated as the party progressed, it was no wonder that he began to feel giddy and the green to wobble about in a strange manner.

On one occasion the morning of May Day was very bright, but also very cold. In the early evening the party returned with the green covered with snow; a snow-storm had started in the afternoon and was continuing as they returned.

Sixty years ago it was not considered May Day if we had not seen at least three Jacks-in-the-Green and their attendants from Rochester and Chatham.

SOOTY ATTENDANTS

Besides the Jack-in-the-Green there was always one man dressed somewhat like an Admiral, wearing white trousers and a crooked hat. He carried a long and large brass spoon, with which he collected the coppers. Several boys and young men in sooty clothes carried their copper shovels which they beat with their brushes, keeping time with the music, and at least half-a-dozen girls and young women dressed in short muslin frocks, like Columbines in a pantomime, and their hair adorned with flowers, would dance round and round the Jack-in-the-Green, beating tambourines in which they also collected coppers as opportunity occurred.

The band usually consisted of two men, one playing a violin and the other a big drum and the pandean pipes… The last of this band… was the wife of the master sweep in her Sunday-best clothes; she walked with the musicians and usually carried a shopping basket which had two flaps. As the money was collected, it was handed to her and a flap of the basket would be lifted and the coins dropped in. By the end of the day it became a weighty load to carry, as the contributions were mostly in coppers.

The author of Dr Syn, Russell Thorndike, in his biography of his sister Sybil (written in 1950) recalls a childhood memory of their time in Rochester where they were brought up:

Another fear we had was Jack-in-the-Green on May Day. Once, two of his mummers hoisted him over the wall, and he called out at us.

The Rochester celebrations were also on the first of May, but the popularity of its revival in the 1970s by Gordon Newton and the Motley morris (which included the rousing of the Jack from his winter slumbers in a nearby woodland at sunrise) has led to its expansion to the whole of the early May bank holiday weekend event entitled the ‘Sweeps’ Procession and May Festival’. The Jack is particularly featured in the Monday afternoon procession through the town, which usually starts from the Castle and features nearly 100 morris sides and groups of youngsters dressed up as ‘climbing boys’.

Other Kent May Customs

The popularity of May garlands and Jacks-in-the-Greens may be connected to the banning of maypoles by Act of Parliament in 1644. Although maypoles were legalised again with the accession of Charles II, they never fully regained their earlier popularity. On May Day 1660, four weeks before the return of the King to England, Samuel Pepys was told ‘how the people of Deale have set up two or three Maypoles and have hung up their flags upon the top of them’. Pepys also records in his diary that his wife went to bathe her face in May morning dew, which was said to be very good for the complexion. In the early sixteenth century, Catherine of Aragon and her ladies-in-waiting had done the same thing in Greenwich Park. Catherine and Henry VIII were treated to an elaborate May Day celebration at Shooters Hill in 1516:

The King and the quene, accompanied with many lords and ladies, roade to the high grounde on Shooters hill to take the open ayre, and as they passed by the way they espied a company of tall yeomen, clothed all in grene, with grene hoods and bowes and arrowes, to the number of two hundred. Then one of them which called hymselfe Robyn Hode, came to the kyng, desyring him to see his men shote, and the kyng was content. Then he whistled, and all the two hundred archers shot and losed at once; and then he whisteled again, and they likewyse shot againe; their arrows whisteled by craft of the head, so that the noyes was straunge and great, and muche pleased the kyng, the queen, and all the company. All these archers were of the kynges garde, and had thus appareled themselves to make solace to the kynge. Then Robyn Hood desyred the kyng and quene to come into the grene wood, and to see how the outlawes lyve. The king demaunded of the quened and her ladyes, if they durst adventure to go into the wood with so many outlawes. Then the quene said if it pleased hym, she was content. Then the hornes blewe tyll they came to the wood under Shooters Hill, and there was an arber made of bowes, with a hall, and a great-chamber, and an inner chamber, very well made and covered with floures and swete herbes, whiche the kyng muche praised. Then said Robyn Hood, Sir, outlaws’ breakfast is venison, and therefore you must be content with such fare as we use. Then the kyng and the quene sate doune, and were served with venison and wine by Robyn Hood and his men, to their great contentacion. Then the kyng departed and his company, and Robyn Hood and his men them conducted; and as they were returnyng, there met with them two ladyes in a ryche chariot drawen with five horses, and every horse had his name on his head, and on every horse sat a lady with her name written… and in the chayre sate the lady May, accompanied with lady Flora, richly appareled; and they saluted the kynge with diverse goodly songs, and so brought hym to Grenewyche. At this maiying was a greate number of people to beholde, to their great solace and comfort.

Bringing maypoles and garlands into communities is an aspect of a wider tradition of decking houses with greenery on May Day of early derivation. In the 1420s the corporation of New Romney paid men from nearby Lydd ‘when they came with their May’. Queen Elizabeth visited Sandwich in early May 1572, ‘every house having a nombre of grene boughs standing against the dores and walls’. May Day was known as ‘Flowering Day’ in Tonbridge in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when Head Boys from Tonbridge School collected flowers from neighbouring gardens to decorate the town and classrooms. On the 2nd or 3rd of May, Masters and Wardens of the Skinners Company (which endowed Tonbridge Public School) visited for a procession and church service and the High Street was decorated with birch boughs. An account of 1799 mentions a dozen old women from the nearby almshouses strewing flowers at the doorway of the school for the governors to walk over. In 1825 the date of this visitation was moved to July.

Morris Dancing

Morris dancing traditions are not as extensive for Kent as for other parts of the south of England but morris dancers are recorded as greeting Charles II in Kent on his return from exile. A parson in 1672 recorded that:

Maidstone was formerly a very prophane town, insomuch that I have seen morrice dancing, cudgel playing, stoolball, cricket, and many other sports, openly and publicly on the Lord’s day.

Sadly, no traditional morris steps survive from Kent, but a number of fine revival teams feature Cotswold morris dances. Stansted Morris originated in 1934 and metamorphosed into Hartley Morris in 1952, which is still going strong, celebrating its 50th anniversary in the year before the writing of this book. The Hartley morris men have an enormous repertoire of over a hundred dances and can be seen dancing outside of many of the most attractive and best ale pubs in West Kent on Thursday evenings in the summer.