Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

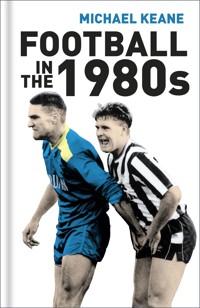

Do you remember a time when footballers' perms were tighter than their shorts? When supporters still swayed on terraces? When a chain-smoking doctor played central midfield for Brazil? Take a nostalgic stroll back to an era when football on TV was still an occasional treat, when almost anyone could finish runners-up to Liverpool and when finishing fourth in the top flight was not a cause for celebration but a sackable offence! Football in the 1980s is an affectionate look at all the essential facts, stats and anecdotes from the decade before the national game was commercially rebranded. Including both some of modern football's darkest days and its most memorable matches, Football in the 1980s will take you back to a time of tough tackles, muddy pitches and cheap seats. Read on for a grandstand view . . .

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 206

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover illustration: Wimbledon’s Vinnie Jones gets to grips with Newcastle United footballer Paul Gascoigne during their League Division One match, 1988. (Mirrorpix)

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Michael Keane 2018

The right of Michael Keane to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8956 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks are due to several people who have helped me put this book together. Firstly, thanks are due to the staff at The History Press, Beth Amphlett, and Mark Benyon, for commissioning and publishing my book. Secondly, thanks are due to my brother Gerard, whose idea it was for me to specialise in the 1980s, and also to my other siblings, Bridget, Richard, Mary and Stephanie, for helping me navigate the decade in one piece. Finally, I would like to thank my own team at home, my wife Gabby and our children Thomas, Oliver, Patrick and Annabelle, who are the stars of my show.

Michael Keane

INTRODUCTION

This book was written almost by chance and certainly for fun. The chance is easy enough to explain, as I will try to, and hopefully the fun will come in the reading of it.

Some time last year, on some errand or other, I found myself trawling through assembled junk in my attic. Once up there, I started to browse around to see what detritus I had insisted on keeping for years. After rummaging through various boxes, I soon found myself staring at the cover of one of my favourite ever singles, ‘My Perfect Cousin,’ by The Undertones, (it reached no. 9 in March 1980, in case you need to know). Whether you know the track or not – though God himself is rumoured to have it on his personal jukebox – does not matter, as it was the cover not the song that sent me spinning back into some serious nostalgia. On that cover is the unmistakable, spindly figure of a Subbuteo player. He is wearing red and white and has a full house cheering him on. This chance discovery sent me racing to find first my old Subbuteo set – just two drooping goal nets and scores of broken players remained – and then, in the next shoebox along, my old programme collection. It was almost entirely from the 1980s, as I drew the line at paying more than £1.00 for a programme many years ago!

Flicking through various old programmes transported me back in time; in an instant, I was once again tuning into World of Sport with Dickie Davies; I was enjoying the wrestling on a Saturday afternoon with my dad; I was listening to the football scores on my tiny transistor; and I was playing with my personally customised Subbuteo set. I had managed to travel nearly three whole decades in the ten minutes me it took me to hop up my attic ladder.

I gazed at programmes featuring badly permed footballers; I cringed with dismay at the fact files documenting players’ favourite meals and actresses; but I warmed to the memories of long-forgotten games that had seemed magical at the time. I had got the nostalgia bug and I couldn’t shake it. In fact, I got it so badly that the idea for this book first germinated and then started to grow.

I hope readers will share my enthusiasm for a decade in which I personally gorged on football. I feasted on FA Cup Finals, wondered at World Cups and simply shook my head at the state of the stadiums. All told, though, it was great fun for me to revisit memory lane and I hope you enjoy the trip too …

LOCK STOCK ANDBOTH BARRELS

In the 1980s there were some things you just took for granted: Margaret Thatcher won general elections, Liverpool won the league every year (almost), and Wimbledon won all the prizes for roughing up their opponents. Tales were plentiful of the The Dons’ antics under the stewardships of Dave Bassett and Bobby Gould: newly-arrived players found their suits were cut, on special occasions players were deposited in car boots and some poor souls were even tossed into canals!

Set against that background of pushing every boundary, the events of an afternoon at Plough Lane in February 1988 are not so hard to figure out. Midfield bulldozer Vinnie Jones was tasked with man-marking Newcastle United’s new kid on the block, a blossoming genius called Paul Gascoigne; he was not so much a bog-standard midfielder – more of a footballing Gandalf, with the tricks, twists and touches of a footballing wizard. For Jones, the afternoon’s assignment was a bit like being asked to try and catch the wind, but not quite so easy.

Faced with the impossible job of nullifying Gascoigne’s brilliance, Jones hatched a plan of his own. Eschewing all recognised tactical nuances, the Dons destroyer instead focused on the basics, and decided that, when the referee was not looking, he would cut off Newcastle’s supply lines by simply grabbing Gazza’s testicles. As the game petered out into a fairly drab 0-0 draw, Newcastle’s number eight was indeed unable to conjure up any great moments of magic, and so, not for the last time, Jones’ utilitarian approach enjoyed a measure of success.

The moment was captured in an image that almost defines the time it was taken in. On one side we see a stony-faced, snarling Jones, seeking any advantage he can muster as he squeezes the life out of an opponent. Then we see the victim, a still cherubic Gazza, wincing and grimacing, as his talent is temporarily reduced to rubble. Way back in the 1980s, in the days before uber-fit athletes and superstar players dominated, football could still make room for all sorts – for artisans and artists, for Jones and Gascoigne, for the good, the bad and the ugly!

ALL SIT DOWN

In the 1960s, under the management of Jimmy Hill, Coventry City quite rightly earned a name for innovation. Sky Blue Specials took travelling supporters on the train to away fixtures, the Sky Blue Pools raised cash and if that wasn’t enough you could also ring up Sky Blue Rose for the latest club news. Those innovations had Hill’s trademark vision all over them and in 1981 he was at it again as he oversaw the planning, design and completion of England’s first all-seater stadium, at Highfield Road.

Increasing disturbances, both nationally and locally, had persuaded the Coventry board that something had to be done to remedy football’s biggest ill. A combination of all-seated spectators, all-ticket matches and increased prices (£1.50 tickets rose to £5.00 if bought on match days), was the strategy, as City planned to price out the troublemakers and appeal to a new ‘family audience’. The opening day of the 1981/82 season saw real optimism as Dave Sexton’s young team beat Manchester United in front of a capacity crowd of 19,329. Briefly it seemed that Hill and Coventry might just be on to something.

Sadly, within weeks Leeds United fans found alternative uses for the shiny new bucket seats, hurling them in all directions; it seemed troublemakers could still make trouble whether standing or seated. The early season optimism soon gave way to some bleak realities, as attendances dipped and disturbances continued sporadically. The first season with seats saw crowds drop almost 20 per cent, and a similar drop in attendances in the second year left the Sky Blues averaging a miserable 10,500 per home game. The well-intentioned and undeniably brave experiment was at best faltering and at worst failing.

Two years after Highfield Road had gone all-seater, Coventry’s board accepted what seemed like the inevitable and decided to partially open the Spion Kop terrace; the scheme had obvious flaws – high pricing in a recession-gripped city was pretty obviously never going to work – but the fact the scheme was attempted gave just a glimpse of what a different type of future match-day experience could be like. Sadly, it would take later events at Hillsborough to force football to understand that change was needed. Coventry, like the rest of the footballing landscape, had just not been ready for the future.

THE GAME OF SHAME

The World Cup in 1982 is fondly remembered for many things – that dazzling Brazilian side, Paolo Rossi’s unparalleled marksmanship, even the tumultuous semi-final between France and West Germany might all spring to mind. One other memory, however, is a less welcome reminder of an otherwise excellent tournament. A match was played in which the normal rules of trying to outscore your opposition were lamentably ignored when West Germany met Austria in their final group match.

West Germany’s campaign had started dreadfully with a 2-1 defeat against unfancied Algeria, it was the first time an African side had beaten any European team, and it put the German’s pre-match predictions of seven or eight goals into sharp focus. Germany did improve, easing past Chile 4-1 in their next outing, while Austria steadily progressed with two successive victories.

Because West Germany and Austria did not play until the following day, when Algeria won their final group match the two European teams had time to race to their calculators to see what result would suit them both. A narrow German win would secure both their own progress and Austria’s, thereby eliminating Algeria. Though the scenario was clear, not many predicted what would pass for a football match the following day in the heat of Gijon.

When European Championship star Horst Hrubesch nodded Germany ahead after ten minutes, the game ended as a contest. The early 1-0 score line suited both teams, guaranteeing each a slot in the second round, so they simply stopped playing. For the remaining eighty minutes, over 40,000 fans whistled and jeered and waved white handkerchiefs as the teams endlessly passed sideways and backwards, mostly without even an opponent within 10 or 15 yards. The idea of a football match was simply abandoned as cynical pragmatism won the day.

Viewers of the match were united in their condemnation of both teams. French coach Hidalgo observed the teams could qualify for the Nobel Peace Prize, while unrepentant German boss Jupp Derwall argued that his only objective had been to progress to the next round. The game though did have one lasting legacy, however, as afterwards FIFA changed the rules to ensure all final group matches be played simultaneously, to avoid further outbreaks of collusion.

THE NUMBERS GAME

It has often been said that you can prove anything with statistics. While that may or may not be true, the following list of head-turning stats might give some food for thought …

£1,469,000 was the British record transfer fee as the 1980s started. It was paid by Wolverhampton Wanderers to Aston Villa for striker Andy Gray. At the time Wolves were a moderately successful top-tier outfit, but the transfer showed their increasing ambitions. After signing on in September 1979, Gray went on to score the winner in that season’s League Cup Final victory over Nottingham Forest and, for a time, the skies above Molineux looked as golden as the team’s shirts. As the decade went on, though, the club’s debts and playing fortunes both spiralled out of control, and after three successive relegations Wolves found themselves in Division Four by 1986.

Twenty-nine matches unbeaten from the start of the season was the run Liverpool’s 1987/88 vintage enjoyed in a league season of unparalleled excellence. Kenny Dalglish’s men equalled the then best-ever unbeaten start set by Leeds United in 1973/74. Bolstered by new signings Aldridge, Beardsley and Barnes, Liverpool were simply a class above most of their opponents as they produced fast-flowing football with a style and a swagger not always associated with previous, more efficient Anfield teams.

Ten straight wins was the blistering start to the league season that Ron Atkinson’s Manchester United team made in the autumn of 1985, with five of the victories being by three goals or more. FA Cup holders United simply tore into their opponents as they hit an irresistible run of form. Goals were shared out between Robson, Stapleton, Whiteside and chiefly Mark Hughes, but wherever you looked United seemed to have goal threats, and after an eighteen-year wait it seemed as if the league title was surely on its way to Old Trafford once again. Despite winning thirteen of their first fifteen matches, United’s title charge hit the rocks when engine-room skipper Bryan Robson endured prolonged layoffs. A collapse in form that extended well into the new year saw United’s title hopes splutter and choke before they finally limped home in fourth spot, having blown their best chance to be champions in a generation.

THE UNLIKELY LADS

On five occasions during the decade, teams went to Wembley and for the first time in their history won a major trophy. If you add on three successive first-timers appearing in FA Cup finals – QPR, Brighton and Watford each losing in their first cup final appearance, from 1982–84 – you might say the eighties were a more meritocratic time; the doors to the trophy cabinets could still be prised open by well-run teams, with a bit of momentum and luck …

1985 Milk Cup Final

Norwich City 1 Sunderland 0

Norwich had more than a bit of history in the League Cup. They had been Second Division winners in a two-legged final against Rochdale back in 1962, and had since lost in two finals in the early 1970s. Sunderland, by contrast, were debuting in the competition’s final, but just a dozen years earlier they had turned the football world into a frenzy by upsetting Leeds United in one of the great FA Cup final shocks.

Norwich and Sunderland struggled for most of the 1984/85 season against the threat of relegation, to which they both finally succumbed, and the distraction of a cup run to Wembley was very welcome. As both teams had found goals hard to come by the final seemed unlikely to be goal-fest – and so it proved, with one solitary goal separating the sides. Just moments into the second half, veteran Asa Hartford steered a shot goalwards only for it to be wickedly and decisively deflected off Sunderland’s Chisolm, leaving keeper Turner helpless in the Sunderland net. Within minutes Norwich had conceded a penalty, but Sunderland’s Clive Walker, probably their biggest threat, fired against a post, and that was the closest Sunderland would come. That year when Norwich finished their league campaign they were eight points clear of lowly Coventry City; unbelievably Coventry went on to win their final three rearranged games and Milk Cup winners Norwich were left with a sour taste in their mouths.

1986 Milk Cup Final

Oxford United 3 QPR 0

Oxford deservedly won their first, and so far only, major trophy with a sparkling attacking display at Wembley against a more fancied Rangers team who were second best all day long. Goals from Hebberd, Houghton and Charles gave United a 3-0 winning margin that did not flatter them; their incisive attacking play was just too much for Rangers.

At the time Oxford were enjoying the most memorable spell in their history, they had gone from Division Three to Division One in two years, going up as champions each year. Manager Jim Smith had overseen the spectacular run, but strangely his contract was not extended by Chairman Robert Maxwell. At the end of the 1985 season Smith took over at QPR, managing them against his old charges in the Wembley final. Oxford’s stay in the top flight lasted only three seasons and the intervening time has not been kind to them, years of decline leading to them slipping out the Football League in 2006. Fortunes have turned again recently though, and these days United are back in League One and have made two more recent visits to Wembley as runners-up in the Football League Trophy finals.

1987 FA Cup Final

Coventry City 3 Tottenham Hotspur 2

The Coventry City team of 1987 were a workmanlike team, organised and gritty, but were perceived to be lacking the star quality of their opponents, Tottenham Hotspur. Spurs’ line up was a who’s who of English football: international star Glenn Hoddle, World Cup winner Ossie Ardiles, forty-eight-goal striker Clive Allen and dazzling wideman Chris Waddle were all names to give Sky Blue fans nightmares.

The final was a thriller for neutrals. Spurs were ahead inside a minute through Clive Allen, and Coventry drew level after ten when Dave Bennett nimbly rounded keeper Clemence to score with a rare left-footed effort. This blistering start set the tone for a match that was dominated by neither team. Instead it ebbed and flowed throughout; the pre-match predictions of Tottenham dominance were certainly wide of the mark.

Spurs nudged ahead after a defensive mix-up led to Gary Mabbutt’s goal shortly before half-time, but just after the hour mark Coventry levelled again. Bennett hit the perfect cross, arcing the ball around the full back for striker Houchen to meet it with a spectacular diving header, as good as any seen in a Wembley final. City’s extra-time winner came courtesy of a deflected Lloyd McGrath cross; it struck Gary Mabbutt’s knee, and in that split second the die was cast. The ball looped up over Clemence and nestled in the far corner of the Tottenham net. For the first time in their 104-year history the Sky Blues had finally won a major trophy.

1988 Littlewoods Cup Final

Luton Town 3 Arsenal 2

When Luton played in this final they were halfway through a ten-year spell in Division One, enjoying the best period in the club’s history. The 1988 team was capable of a third consecutive top-ten finish and included some players other teams envied and feared in Mark Stein and Mick Harford. Opponents Arsenal, under George Graham, were emerging as top-six side who had already won the previous year’s Littlewoods Cup. They were on the up and were clear favourites for the ’88 final.

After thirteen minutes, Luton’s Mark Stein opened the scoring, smartly side-footing a through-ball home, and it was a lead they held for almost an hour. With less than twenty minutes remaining, Arsenal hit back with two goals in three minutes to turn the match around. Luton’s chances seemed to be slipping away when they then conceded a penalty, but reserve keeper Dibble pulled off another magnificent diving save, this time to his left, and they breathed again. Shortly afterwards, a bouncing ball in the Arsenal penalty area was not dealt with by Gus Ceasar, who famously stumbled as he tried to clear it, allowing Mark Stein to set up Danny Wilson for an equaliser. With the match just seconds from extra-time Luton sub Ashley Grimes crossed first time with the outside of his left foot and that man Stein was there again to steer a volley into Arsenal’s net and complete the incredible turnaround.

With little over ten minutes left Luton had trailed 2-1 and faced a penalty against them. They were not so much on the ropes as on the canvas, but thanks to some inspired goalkeeping and smart forward play they had roused themselves to deliver a stunning knockout blow.

1988 FA Cup Final

Wimbledon 1 Liverpool 0

This cup final is often heralded as the ultimate David v. Goliath showdown, and while that might be overstating things a little, as Wimbledon had finished seventh in Division One to Liverpool’s first place, the shock the Dons created by winning could have registered on the footballing Richter scale! How the footballing world was turned upside down can be read in more detail elsewhere.

SIMPLY THE BEST

At the 1982 World Cup finals, Brazil manager Telê Santana had a dream-come-true of a team. His list of talented individuals was long: Junior, the free-roaming full back who could appear anywhere; Socrates, the chain-smoking doctor with the deftest of touches, in the middle of the field; Zico, unlocking any defence with more tricks than Paul Daniels, up front. Santana’s boys looked expertly equipped to launch the country’s first serious attempt at the World Cup since the days of Pelé, Jairzinho and Carlos Alberto.

Brazil’s first match against the USSR signposted what they had in their team; trailing 1-0 after a goalkeeping fumble they produced two goals of the highest quality to win. Firstly, Eder hit a firecracker of a volley to level things up after the most insouciant of dummies from Falcao, before Socrates won it with an arrowing shot of such velocity that it might be still travelling if it had not hit the top corner of the Russian net. They were exhibition goals on the highest stage.

Next up were a Scotland team that had a few highly regarded players of their own, with a spine from Liverpool’s all-conquering team in Hansen, Souness and Dalglish. The Scots had the cheek to open the scoring with a superb David Narey strike from distance, but this was a bit like waking a sleeping tiger; once Brazil were roused there was only ever one possible outcome. First, Zico’s free kick hit the topmost point of Alan Rough’s left-hand post, leaving the keeper motionless. Then, Oscar’s header followed, before another very special strike, this time Eder chipping the static, suffering Rough to perfection from just inside the left-hand side of the penalty area. A thumping strike from outside the area by Falcao finished the scoring, but in truth this was less of a contest and more of a coronation; on this evidence, against a decent Scottish side, Brazil were playing on another level.

The routine four goal demolition of New Zealand that finished the group matches included two more memorable strikes from Zico – a scissor-kick volley and a calm side-foot after a perfect passing move. Argentina and Italy were up next, but neither had offered anything like the verve and firepower the Brazilians had demonstrated; Santana’s men were now not just favourites for the competition, they were favourites for the millions watching around the world and revelling in wave after wave of golden, attacking football.

Argentina were comfortably beaten 3-1: Zico poked in a rebound from Eder’s fierce free-kick, Serginho popped up with a header before the marauding Junior added a sublime third, racing on to Zico’s precision pass. Brazil were strong and seemingly getting stronger with each outing. The quality of the goals they were scoring was striking. If Michelangelo’s dad had given his teenage prodigy a pair of size 9 pumas instead of a paintbrush, he would surely have scored goals like these – they were skilful, incisive and thrilling; they were masterpieces.

All Brazil had to do was just keep up perfection, but next in line were the masters of spoiling and squeezing, the improving Italians. The Azzurri had a chance against anyone, as they had a gunslinger of a forward called Paolo Rossi whose shooting could be deadly. After five minutes it was first strike to Rossi, who nodded home only for the languid Socrates to calmly level soon afterwards – fifteen minutes in and we had a match on our hands.

Ten further minutes were played before what was perhaps the decisive moment of the match occurred: Cerezo’s square pass along his back line went straight to Rossi, who advanced, took aim and scored – 2-1 to Italy at half-time. Just after the hour, Falcao benefited from one of the cutest decoy runs you will ever see from Cerezo. In the blink of an eye his dummy run took out three Italian defenders, allowing Falcao to stride forward into into an empty penalty area and shoot powerfully past Zoff, now looking his whole 40 years of age.

Had Brazil only been able to hang on to the 2-2 scoreline, the semi-final berth was theirs. Had they been able to pick up Paolo Rossi, who completed his hat-trick when left unmarked at a corner, things would have been different. But this Brazilian team was a throwback to more light-hearted days, where you just played your game and did not worry too much about the opposition. Brazil’s own Achilles heel was the defence that sometimes patrolled behind their magical midfield; what they needed was a scrapper or a stopper, a Scirea, or a Gentile, rugged as the Rockies. Sadly for Brazil, though, there was no such ballast in the defence and the team that thrilled so many were soon packing their suitcases for home. The dream of relentless, carefree attacking football had run aground on the stony rocks of Italian pragmatism. On this occasion, perhaps sadly, the artists were undone by the artisans.