Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

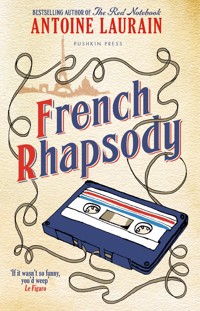

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Discontented middle-aged doctor Alain Massoulier has received a life-changing letter - thirty-three years too late. Lost in the Paris postal system for decades, it offers a recording contract to Alain's old band The Holograms, which split up long ago.Now, overcome by nostalgia, Alain decides to track down his old bandmates - including the alluring singer he secretly loved. But in a world where everything and everyone has changed, where will his quest take him?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 279

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1praise forFrench Windows

‘Masterful storytelling that brings the streets of Paris to life. And enough twists and turns that will leave you wondering what the hell is going on right until the last page’

Sun

‘Intriguing, comic and poignant by turns, this is a sheer delight’

Guardian

‘This short but sweet mystery is … a delicious jeu d’esprit’

The Times

‘French Windows oozes Parisian perfection with a good dose of mystery, intrigue, and suspense from a master storyteller’

Chicago Book Review2

praise forAn Astronomer in Love

longlisted for the dublin literary award 2024

shortlisted for the edward stanford viking award for fiction 2024

winner of the prix de l’union interallié and the grand prix jules-verne 2023

‘Perfect for the poolside or sitting outside a café with a pastis and olives – and bound to give you just the same cheering lift’

The Times

‘A brilliant love story … The supporting cast, including a not-quite-dead dodo and a zebra, will have readers laughing and crying in equal measure’

The Lady

‘Cinematic and enchanting’

ForewordReviews(starred)

‘Simply beautiful. An enchanting dual-timeline story of a love written in the stars’

Fiona Valpy, author of TheDressmaker’sGift

‘A witty, lovely, surprising triumph’

William Ryan, author of AHouseofGhosts

praise forVintage 1954

‘A glorious time-slip caper … Just wonderful’

Daily Mail3

‘Delightfully nostalgic escapism set in a gorgeously conjured Paris of 1954’

Sunday Mirror

‘Like fine wine, Laurain’s novels get better with each one he writes … a charming and warm-hearted read’

Phaedra Patrick, author of The Curious Charms of Arthur Pepper

praise forThe President’s Hat

‘A hymn to la vie Parisienne … enjoy it for its fabulistic narrative, and the way it teeters pleasantly on the edge of Gallic whimsy’

Guardian

‘Flawless … a funny, clever, feel-good social satire with the page-turning quality of a great detective novel’

Rosie Goldsmith

‘A fable of romance and redemption’

Telegraph

‘Part eccentric romance, part detective story … this book makes perfect holiday reading’

The Lady

‘Its gentle satirical humor reminded me of Jacques Tati’s classic films, and, no, you don’t have to know French politics to enjoy this novel’

Library Journal4

praise for The Red Notebook

‘A clever, funny novel… a masterpiece of Parisian perfection’

HM The Queen

‘In equal parts an offbeat romance, detective story and a clarion call for metropolitans to look after their neighbours… Reading The Red Notebook is a little like finding a gem among the bric-a-brac in a local brocante’

Telegraph

‘Resist this novel if you can; it’s the very quintessence of French romance’

The Times

‘Soaked in Parisian atmosphere, this lovely, clever, funny novel will have you rushing to the Eurostar post-haste… A gem’

Daily Mail

‘An endearing love story written in beautifully poetic prose. It is an enthralling mystery about chasing the unknown, the nostalgia for what could have been, and most importantly, the persistence of curiosity’

San Francisco Book Review

5

6

7

8

9

Within all of us there are secret things, obscure, profound impressions, which, like the rest of our previous existence or the glimmerings of a future life, are a sort of psychic dust, ash or seed, to be remembered or foreseen.

Henri de RégnierLes Cahiers (1927)10

Rhapsody:

In classical music, a rhapsody is a free composition for a solo instrument, several instruments or a symphony orchestra. Quite similar to a fantasia, a rhapsody almost always draws on national or regional themes.12

A Letter

The assistant manager, a tired-looking little man with a narrow, greying moustache, had invited him to sit down in a tiny windowless office brightened only by its canary-yellow door. When Alain saw the carefully framed notice, he felt nervous laughter return – but more hysterical this time, and accompanied by the disagreeable feeling that if God existed, he had a very dubious sense of humour. The notice showed a joyful team of postmen and -women all giving the thumbs up. Running across the top in yellow letters were the words ‘The future: brought to you by the Post Office.’ Alain chuckled mirthlessly. ‘Great slogan.’

‘No need to be sarcastic, Monsieur,’ replied the civil servant calmly.

‘Don’t you think I’m entitled to a little sarcasm?’ demanded Alain, pointing to his letter. ‘Thirty-three years late. How do you explain that?’

‘Your tone is not helpful, Monsieur,’ replied the man drily.

Alain glared at him. The assistant manager held his gaze for a moment, then slowly extended his arm towards a blue folder which he opened with some ceremony. Then he licked his finger and started turning the pages, rather slowly. ‘And your name is?’ he murmured, not looking at Alain.

‘Massoulier,’ replied Alain.

‘Ah, yes, Dr Alain Massoulier, 38 Rue de Moscou, Paris 148e,’ the civil servant read aloud. ‘You’re aware that we’re modernising?’

‘The results are impressive.’

The man with the moustache looked at Alain again in silence and seemed about to say something sharp, but apparently thought better of it.

‘As I was saying, the building is being modernised, so all the wooden shelves, dating back to its construction in 1954, were taken down last week. The workmen found four letters which had fallen down the back and were trapped between the floor and the shelves. The oldest dated back to … 1963,’ he confirmed, reading from the file. ‘Then there was a postcard from 1978, a letter from 1983 – that’s yours – and lastly, a letter from 2002. We took the decision that, where possible, we would deliver them to their recipients if they were still alive and easily identifiable from their addresses. That’s the explanation,’ he said, closing the blue file.

‘But no apology?’ said Alain.

Eventually the assistant manager said, ‘If you wish, we can send you our apology form letter. Would that be of use?’

Alain looked down at the desk where his eye fell on a heavy cast-iron paperweight, embellished with the insignia of the postal service. He briefly saw himself picking it up and hitting the little moustachioed man with it repeatedly.

‘For whatever purpose it may serve,’ droned the man, ‘does this letter have a legal significance (with regard to an inheritance or transfer of shares or similar) such that the delay in delivery would activate legal proceedings against the postal service—’

‘No, it does not,’ Alain cut him off brusquely.

The man asked him for his signature at the bottom of a form that Alain did not even bother to read. Alain left and stopped 15outside in front of a skip. Workmen were throwing solid oak planks and metal structures into it, shouting at each other in what Alain believed was Serbian.

Passing a mirror in a chemist’s window, Alain caught sight of his reflection. He saw grey hair and the rimless glasses that his optician claimed were as good as a facelift. An ageing doctor, that’s what the mirror reflected back at him, an ageing doctor like so many thousands of others across the country. A doctor, just like his father before him.

Written on a typewriter and signed in turquoise ink, the letter had arrived in the morning post. In the top left-hand corner was the logo of the famous record label: a semicircle above the name, featuring a vinyl record in the form of a setting sun – or maybe a rising sun. The paper had yellowed at the edges. Alain had reread the letter three times before putting it back in the envelope. His name was correct, his address was correct. Everything was in order except for the date, 12 September 1983. That date was also printed over the stamp – a Marianne that had been out of circulation for a long time. The postmark was only half printed but you could clearly read: Paris – 12/9/83. Alain had suppressed a fleeting guffaw like an unwelcome tic. Then he had shaken his head, smiling incredulously. Thirty-three years. That letter had taken thirty-three years to travel across three arrondissementsof the capital.

The day’s post – an electricity bill, LeFigaro, L’Obs, three publicity flyers (one for a mobile phone, one for a travel agent and the third for an insurance company) – had just been brought up by Madame Da Silva, the concierge. Alain had considered getting up, opening the door and catching Madame Da Silva on the stairs to ask her where the letter had come from. But 16she would already be back downstairs in her apartment, and anyway, she wouldn’t be able to help him. She had merely brought up what the postman had delivered to the building.

Paris, 12 September 1983

Dear Holograms

We listened with great interest to the five-track demo tape you sent us at the beginning of the summer. Your work is precise and very professional, and although it needs quite a bit of work, you already have a sound that is distinctive. The track we were most impressed by was ‘Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On’. You have managed to blend new wave and cold wave whilst adding your own rock sound.

Please get in touch with us so that we can organise a meeting.

Best wishes

Claude Kalan

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR18

The tone was polite but friendly. Alain focused on the words ‘precise’ and ‘very professional’ whilst noting the slightly derogatory repetition of the word ‘work’. And the letter ended on an encouraging note, an affirmation in fact. Yes, thought Alain, ‘Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On’ was the best, a jewel, a hit, whispered in Bérengère’s voice. Alain closed his eyes and recalled her face with almost surreal precision: her big eyes, always vaguely worried, her short haircut with the fringe sweeping over her forehead, the way she had of going up to the mic and holding it with both hands and not letting go for the whole song. She would close her eyes and the soft voice with its touch of huskiness was always a surprise coming from a girl of nineteen. Alain opened his eyes again: ‘a meeting’ – how many times had the five of them uttered that word. How many times had they hoped for a meeting with a record label: a meeting at eleven on Monday at our offices. We have a meeting at Polydor. That ‘meeting’ had never been forthcoming. The Holograms had split up. Although that was not exactly the right term. It would be more accurate to say that life had simply moved on, causing the group to disperse. In the absence of a response from any record label, they had each gone their own way, disappointed and tired of waiting.

Still half asleep in her blue silk dressing gown, Véronique had just pushed open the kitchen door. Alain looked up at her and handed her the letter. She read it through, yawning.

‘It’s a mistake,’ she said.

‘It certainly is not,’ retorted Alain, holding out the envelope. ‘Alain Massoulier, that’s me.’

‘I don’t understand.’ Véronique shook her head, indicating that untangling an enigma so soon after waking up was beyond her.19

‘The date, look at the date.’

She read out, ‘1983.’

‘The Holograms, that was my group, my rock group. Well, it wasn’t rock, it was new wave; cold wave to be exact, as it says here.’ Alain pointed to the relevant line in the letter.

Véronique looked at her husband in astonishment.

‘The letter took thirty-three years to travel across three arrondissements.’

‘Are you sure?’ she murmured, turning the letter over.

‘Have you got another explanation?’

‘You’ll have to ask at the post office,’ concluded Véronique, sitting down.

‘I’m going to! I wouldn’t miss that for the world,’ replied Alain.

Then he got up and started the Nespresso machine.

‘Make me one,’ said Véronique, yawning again.

Alain thought it was time his wife cut down on the sleeping tablets. It was distressing to see her every morning appearing like a rumpled shrew. It would take her at least two hours in the bathroom before she emerged dressed and made up. So all in all it took nearly three hours for Véronique to get herself properly together. Since the children had left home, Alain and Véronique found themselves living on their own as at the beginning of their marriage. But twenty-five years had passed and what had seemed charming at the beginning was becoming a little wearing, and now long silences stretched out over dinner. In order to fill them Véronique talked about her clients and her latest decorative finds, while Alain would mention patients or colleagues, and then they would fall to discussing their holiday plans although they could never agree where to go.

Backache

Alain stayed in bed for a week. The day the letter had arrived, he’d been laid low with backache which he first diagnosed as lumbago, then sciatica, or maybe neuralgia. Or perhaps the cause was not medical at all. He hadn’t carried anything heavy, or made a sudden movement and heard a suspicious crack. He couldn’t exclude the possibility that the pain was psychosomatic. But whatever the cause, it didn’t change the fact that he was lying in bed, in his pyjamas, with a hot-water bottle under his back. He was on painkillers and moved around the flat like an old man, taking little steps, with a look of suffering on his face. He had instructed his secretary, Maryam, to cancel all his appointments until further notice and then go home herself.

The day the letter arrived had seemed endless. Like some strange mirror effect the letter’s thirty-three-year delay seemed to have infected the passage of time, causing it to slow down. At four o’clock, Alain felt as if he’d been in his consulting room listening to the ills of his patients for about fifteen hours. Every time he opened the door to the waiting room, it seemed to have filled up again. An outbreak of gastroenteritis was the reason for all the people. He had listened to dozens of accounts of diarrhoea and stomach cramps. ‘I feel as if I’m going to shit my brains out, Doctor!’ had been the colourful expression the local 21butcher had used. As Alain listened to him, he decided to stop buying meat from him.

The day should have passed in calm contemplation. You think you have buried your youthful dreams, that they’ve dissolved in the fog of passing years and then you realise it’s not true! The corpse is still there, terrifying and unburied. He should have found a grave for it and something funereal should have followed his reading of the letter, funereal and silent, accompanied by incense. Instead, it seemed as if the entire city had made its way to his apartment to regale him with sordid tales of their intestines, their diarrhoea, and their flushing toilets.

Little Amélie Berthier, eight years old, had come with her mother. She didn’t have a stomach bug, she had a sore throat and repeatedly refused to open her mouth. Sitting on the edge of the examination table, the little minx shied away, shaking her head, every time Alain approached with the disposable tongue depressor and torch.

‘You must sit still,’ he said sternly.

The child had calmed down immediately and let her throat be examined without any more fuss. Alain then wrote the prescription in heavy silence.

‘She needs discipline,’ her mother volunteered reluctantly.

‘Possibly,’ replied Alain coldly.

‘But what can you expect with a father who’s never there …’ said the mother, leaving the sentence unfinished in the hope that the doctor would ask her about it.

Alain did not. After ushering them out, he allowed himself a few minutes’ break, massaging his temples.

The surgery had ended at twenty past seven with a patient whose eczema had flared up again and who had come to add his 22contribution to the day. Before that there had been an earache, a urinary tract infection, several cases of bronchitis and more gastroenteritis. Alain had uttered the somewhat pompous phrase ‘intestinal flora’ several times. He had often noticed that patients with stomach bugs liked to be told they ‘must boost their intestinal flora’. They always nodded gravely. Becoming the careful gardener of their insides was a project that gave them purpose. After accompanying his eczema patient to the door, Alain washed his hands thoroughly and then poured himself a strong whisky in the kitchen. He practically downed it in one. Then he went out to one of the cupboards in the corridor and started to empty it. Soon the iron, diving masks, files, beach towels, and folders of the children’s schoolwork were spread all over the floor. He wanted to find an answer to the question that had been nagging at him all day – had he kept the shoebox containing his photos of the group and the cassette? He wasn’t sure any more. He could clearly picture it on the upper shelf where it had been for years. Had he plannedto throw it out or had he actuallythrown it out? The assorted pile of little-used objects expanding on the carpet seemed to indicate the latter. It was maddening. The only thing Alain wanted to do at that precise moment was to put the tape into the old Yamaha cassette player and listen to the band again. And he especially wanted to hear ‘Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On’. The music and Bérengère’s voice had been playing in his head all day.

‘Idiot, idiot, idiot …’ muttered Alain. He must indeed have thrown it away. Now he remembered. He’d wanted to sort out the cupboard two or three years ago, over the long Easter weekend. He’d used a large bin bag and he must have chucked the box in without even opening it, in amongst the out-of-date bills and the old shoes no one wore any more. He had even 23thrown away things from his parents’ time which hadn’t been moved for years.

At the back of the cupboard, behind three overcoats, he spied the black case with Gibson on it and at his feet he saw the Marshall amplifier. He pulled the case out carefully and unzipped it. The black lacquer of the electric guitar was as shiny as ever; time had not taken its toll. Ten years ago his children had asked to see it and Alain had shown it to them although he had refused to play anything. They thought it was funny that not only did their father possess an electric guitar, but that he actually knew how to play it. Alain ran his fingers over the strings then quickly zipped up the cover and put the guitar back in the cupboard behind the winter coats. That was when he noticed his back was hurting. An hour later he was in bed.

Sweet Eighties

It had all started with an advert in Rock&Folk. ‘New-wave band the Holograms and their singer Bérengère seek electric guitarist. Good standard required for young but motivated group. Come and audition before we get famous!’ Alain had turned up at the appointed place: the garage of a house in Juvisy belonging to the parents of the bass guitarist who’d been recruited a few weeks earlier by the same method. That afternoon three boys tried out and Alain had been chosen after giving a rendition of part of Van Halen’s ‘Eruption’,a bit of Queen, and Pink Floyd’s ‘Another Brick in the Wall’.

It’s always the same with bands. A group of individuals with different aims get together united by a love of music. They play on their own at home and want to meet other guys and girls who also play on their own at home. They want to create the kind of sound that’s not on the radio. They feel they’ve captured the essence of their era and they want to share it with their generation and more widely with that vast, mysterious entity called ‘the general public’. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Indochine and Téléphone all started like that – with an advert, a meeting and a stroke of luck. At that time when you still have your whole life ahead of you, when the field of possibilities seems wide open, at that age when you can’t for a moment imagine being fifty-two – even the thought of it seems a fantasy. You’re going to be twenty for eternity and beyond, 25and what’s more, you are exactly what the world is waiting for. As a general rule, you are still untouched by tragedy: you still have your parents; your life, and that of those around you, is stable. Everything is possible.

Vocals: Bérengère Leroy

Electric guitar: Alain Massoulier

Drums: Stanislas Lepelle

Bass: Sébastien Vaugan

Keyboard: Frédéric Lejeune

Music by: Lejeune/Lepelle

Words by: Pierre Mazart

Produced by: The Holograms and ‘JBM’

One girl, four boys. That was the Holograms. Five people from diverse backgrounds who would never otherwise have met, drawn together by music. A middle-class doctor’s son: Alain. A provincial girl from Burgundy who dreamt of being a singer and had come to Paris to study at the École du Louvre: Bérengère. A dentist’s son from Neuilly, enrolled at the Beaux-Arts but only interested in drums: Stanislas Lepelle. The son of a train driver who played synthesiser and longed to be a songwriter: Frédéric Lejeune. And finally the son of a cobbler from Juvisy with a little shoe-repair and key-cutting shop: Sébastien Vaugan, who could play bass guitar like no one else. Then Pierre Mazart, their lyricist, had arrived. A bit older than them and with no connection to music, he sold objets d’art and was destined to be an antique dealer. Passionate about literature and poetry, he had taken up the challenge of songwriting in English and was responsible for the track that would have been their hit, ‘Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On’. It was a 26quote from Shakespeare, a mysterious, esoteric quote which fitted the new-wave aura perfectly. Bérengère had met him at a party thrown by students at the École du Louvre, along with his younger brother, Jean-Bernard Mazart, known as JBM.

Stretched out on his bed, Alain was hit by a sudden wave of nostalgia, or perhaps it was despondency, maybe even the beginning of depression. In any case, none of the props of his trade – stethoscope, blood pressure cuff, syrups, pills – would be any use in diagnosing the problem or supplying a remedy.

When the Holograms were around, there had been forty-fives; he would go and buy them at the record shop or at Monoprix. The record shop had been replaced by a grocer whose late opening had seen off the Félix Potin on the street. And that shop had changed hands several times before becoming what it was today, a phone shop selling the latest iPhones and iPads with their apps for downloading music or film.

The photographic shop had also disappeared. You would go there to buy Kodak films with twelve, twenty-four or a maximum of thirty-six exposures, and sometimes when you collected them a week later, half the pictures were fuzzy. Now even the cheapest mobile phone allowed you to take more than three thousand photographs for free, visible immediately and often of extremely high quality. Uttering the phrase ‘I’ll just take a photo with my phone’ would have made you sound like a lunatic thirty-three years ago, thought Alain. Being able to phone anyone you liked in the street was not even a dream in 1983, not even an idea, not even foreseen. Whatfor?most people would have replied to the idea of an iPhone.

What remained now of the 1980s? Very little, if anything, 27concluded Alain. Television channels had multiplied from six to more than a hundred and fifty according to the satellite subscription he had. Where there used to be just one remote control, now you had to juggle with three (flat-screen TV, DVD player and satellite box). These machines were constantly updating and three-quarters of their buttons remained an unused mystery. Everything was digital now and so sophisticated that it was possible to do almost anything sitting in a café. The web had given unlimited access to everything, absolutely everything: from Harvard courses to porn films, by way of the rarest of songs that previously only a few fanatics scattered across the world would have possessed on vinyl, but which were now available to anybody on YouTube.

The print editions of the Encyclopædia Britannica and its door-to-door salesmen no longer existed – everything was on Wikipedia. The medical dictionary with its horrifying illustrations which had previously been the domain of professionals was now available to absolutely anyone in three clicks. And there were forums where patients played at being trainee doctors. In never-ending discussions sometimes going on for several years. Laymen, with no one to moderate their opinions, exchanged erroneous diagnoses and inappropriate treatments. For a long time now, Alain had had to put up with patients interrupting him with the infamous ‘Yes, but, Doctor, I read on the internet …’

And what of the ‘idols’ of that era? David Bowie had emerged from his British solitude to launch a final album, Blackstar, only to bow out of life two days later. The accompanying video was a carefully orchestrated farewell to his fans. U2’s Bono only cared about poverty and about becoming Secretary General of the United Nations – and perhaps that’s what he would become one 28day. Ravaged by plastic surgery, Michael Jackson had finished his life as a quasi-transsexual dependent on sleeping pills right up until the final overdose, with his career overshadowed by sordid rumours of his behaviour with little boys. As for the enigmatic Prince, before he was found dead at his Paisley Park studios, he had only made rare appearances for unexpected secret concerts, and other than that only communicated through the web, making new songs available for download. No one knew if he still had a following who bought them.

Of course there were idols today. Alain knew about Eminem, Adele, Rihanna and Beyoncé, but beyond that … The few times he had seen them on music channels had convinced him that the vast majority of music produced round the world today oscillated between rap and pop, sometimes a fortuitous blend of the two, and invariably involved videos of young girls dressed like high-class prostitutes, wearing too much make-up and gyrating around gleaming expensive cars. All the songs sounded the same; they were quite stirring, but aimed squarely at fickle adolescents, who would quickly move on and forget them. The Holograms did not have that problem: no one had forgotten them because no one had ever heard of them.

Enthusiastic Beginnings

They would get together to practise at the weekend. Usually in Juvisy, in the garage of Sébastien Vaugan’s neat stone villa. Sébastien’s father’s Peugeot 204 had to be driven out and parked on a little side street first. Vaugan, who had just passed his driving test, took care of that, mostly before the others arrived. At the back of the garage there were lots of tools attached to the wall and there was a wood lathe which the cobbler had used to make his dining-room table and chairs himself. In addition, there was an old Communist Party poster probably dating back to the sixties, which exhorted the workers to unite for the Revolution. Vaugan wouldn’t talk about that. His father was a member of the Party, but Vaugan was a reserved young man who never spoke about his personal life apart from bass and records.

Bérengère had encountered Lepelle one afternoon when she was going to meet her boyfriend at the Beaux-Arts. The brass band of the famous college was in full flow in the courtyard and Lepelle was in charge of taking the money. In a break, Lepelle had hurried over to the young girl who was watching the band play and smoking a cigarette.

‘What you’re listening to is rubbish. I don’t care about that poxy band or about taking money. What I’m into is drums. I’d like to join a group, a real group. I want to be a drummer.’30

‘Like Charlie Watts?’ Bérengère had asked him.

‘Better than Charlie Watts!’ Lepelle had replied. ‘He’s not that good, Charlie Watts, although I’m glad you mention him; normally when people talk about the Stones they only talk about Mick Jagger or Keith Richards. Are you into music?’

Bérengère had replied that she was a singer. Two months earlier she had discovered a piano-bar in a cellar near Notre-Dame, called L’Acajou. She had gone for an audition and now sang there two nights a week from ten o’clock until midnight. She earned a hundred and fifty francs a night, just pocket money. She sang Barbara, Gainsbourg, a bit of Sylvie Vartan, but what she loved most was Bowie and, more than anything, ‘wave’.

Lepelle had gone to L’Acajou one evening and met the pianist. He said he was a bit too old to set up a group, but he knew a lad who was great on keyboards – the son of an old regiment mate by the name of Frédéric. He gave them his phone number. Frédéric Lejeune joined their project. The first three Holograms were therefore keyboards, drums and a singer, and they played at open-air concerts and in little suburban venues.

One evening, Lepelle suddenly said, ‘Would you like to go out with me? You’re very beautiful, really.’

‘Thanks for the “really”.’

‘I didn’t mean it like that. You know what I meant …’

There had been an embarrassed silence, then Lepelle heard her say, ‘You’re cool, Stanislas, but I don’t want to go out with you.’

‘OK,’ Lepelle said reluctantly, ‘well, we’re not going to break up the group over this.’ He then went on, mendaciously, ‘Anyway, I have so many girls after me at the Beaux-Arts, I can’t handle them all.’

31It was decided that they should make the group bigger. They couldn’t carry on with just the three of them; they needed a bass player and an electric guitarist. And also they couldn’t just go on doing cover versions, they needed to write their own songs. Frédéric Lejeune composed nice tunes, but, according to Lepelle, they lacked ambition. A guitarist and a bassist would bring a new element. The three decided to put an advert in Rock&Folk. Ten bassists turned up. Most of them were not nearly good enough, but then Vaugan began to play. When he finished his piece, he looked up and murmured, ‘I don’t do that very often, it’s my first audition.’

‘And your last,’ Lepelle responded, ‘because you’re with us now. Don’t you agree, Bérengère?’

Then there had been the audition for the guitarist and Alain was chosen. Now the Holograms were five.

Lejeune’s melodies improved, Bérengère’s voice became more and more assured, Alain perfected his solos whilst studying for second-year medicine, Lepelle neglected the studios of the Beaux-Arts in order to concentrate on his drumming and Vaugan’s playing remained excellent even though he was busy with his carpentry training. But the words of their songs still posed a problem. Lepelle had undertaken a first draft of three songs but the words were ridiculous: mysterious girls, nights without end under a red moon, what a boon. Alain had tried to write one too but no one had liked that either. Vaugan refused even to try, as did Lejeune. They had quite liked Bérengère’s attempts, but judged them a bit too feminine.

They looked into the cost of hiring a studio but it was exorbitant so they had opted instead to record some songs in the Vaugans’ garage. This necessitated stopping mid-song when a moped went by or when the neighbour’s dog barked. 32The resulting sound was not great, but acceptable for a demo to be sent to a record company. In the end, though, the group decided to wait until they had ‘something mind-blowing’, to quote Alain, before they sent anything off.

‘You’re right, man,’ Lepelle decided, ‘we need a songwriter and a proper studio. And we’ll have to sing in English if we want to have worldwide appeal. We’re not trying to be Indochine or Téléphone. We want to be better than U2, better than the Eurythmics, better than Depeche Mode. We’re the Holograms and we’re going to be the best!’