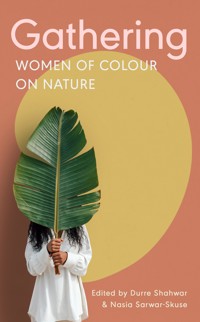

Gathering brings together essays by women of colour across the UK writing about their relationships with nature, in a genre long-dominated by male, white, middle-class writers. In redressing this imbalance, this moving collection considers climate justice, neurodiversity, mental health, academia, inherited histories, colonialism, whiteness, music, hiking and so much more. These personal, creative, and fierce essays will broaden both conversations and horizons about our living world, encouraging readers to consider their own experience with nature and their place within it.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 219

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Gathering

Published by 404 Ink

www.404Ink.com

@404Ink

First published in Great Britain, 2024

All rights reserved © respective authors, 2024.

The right of the authors to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining the written permission of the copyright owner, except for the use of brief quotations in reviews.

Editing: Durre Shahwar & Nasia Sarwar-Skuse

Illustrations: Haricha Abdaal

Typesetting: Laura Jones-Rivera

Proofreading: Laura Jones-Rivera

Cover design: Holly Ovenden

Co-founders and publishers of 404 Ink:

Heather McDaid & Laura Jones-Rivera

Print ISBN: 9781912489749

Ebook ISBN: 9781912489756

404 Ink acknowledges and is thankful for the financial support of

Books Council of Wales and Creative Scotland in the publication of this title.

Gathering

Women of Colour on Nature

edited by Durre Shahwar & Nasia Sarwar-Skuse

Contents

Foreword

A British-Ghanaian in the West Country: On symbols, myths and reimagining the British Countryside – Louisa Adjoa Parker

Nature is Queer: We Could Learn a Thing or Two from That – Jasmine Isa Qureshi

The Stones of Scotland / (a)version – Alycia Piromohamed

A Pencil, a Trowel and a Dinosaur Bone – Katherine Cleaver

From God We Come and To God We Return – Dr Sofia Rehman

In a Relationship with Sugar – Maya Chowdhry

I am Punk by Nature – Nadia Javed

The Gift of Healing – Susmita Bhattacharya

The Sacred Arbor: Trees, Mythology and Islamic Perspectives – Hanan Issa

an ecostory – Khairani Barokka

Until We Turn the Tide – Tina Pasotra

The Nature of White Sustainability – Sharan Dhaliwal

World and Being – Kandace Siobhan Walker

I Walk, the Sea Rises – Taylor Edmonds

Flowerpots – Durre Shahwar

Nature: A Recollection, A Reclamation – Adéọlá Dewis

Acknowledgements

Contributor Biographies

Editor Biographies

Illustrator Biography

Foreword

A cursory glance in any bookshop or library reveals that books on nature and climate crisis are predominantly written by white authors, while writers of colour are often overlooked. Yet the impact of the climate crisis is felt keenly by marginalised communities worldwide, particularly in the Global South. It is precisely this absence of intersectional stories, and the desire to amplify nature writing by women of colour, that led to the creation of this anthology.

Gathering arose out of a residency Durre undertook a few years ago, in which she explored her connection with the Welsh landscape as a woman of colour. She came to the end of that residency realising that there was more to be done; more writing and art by people of colour about nature, more inclusion of our voices in the fight to save our planet, and more autonomy over what we write about and how we write about it. Following insightful conversations between Durre and Nasia, the project gained its momentum.

Gathering felt fitting then as a title. A noun and a verb at once, signifying a move away from the individual into the collective, physically, and symbolically as this anthology does. The Welsh word for anthology is ‘blodeugerdd’. When translated literally, ‘blodeu’ means ‘flowers’ and ‘cerdd’ usually means ‘poem’ or ‘verse’. So ‘the flowers of verse’. The essays in Gathering aren’t poems or ‘flowery’ in the way that a literal meaning of both of those words might imply, nor in the way that writing by women about nature often gets negatively labelled as – quaint and twill. But what they do contain are different textures, colours, and scents that a verse of flowers might do. There are essays about the benefits of cold sea swimming, overcoming fear of solo hikes, the joy of discovery, the heartache of loss, the symbiosis of nature and faith, complex historical and contemporary narratives of exploitation and environmental destruction, as well as narratives of hope. All these essays underly a personal aspect that speaks to the embodied connection that we all have to whatever part of this earth that we occupy. The writers centre the environment from a backdrop to a protagonist, inviting us to explore the outer landscapes and the depths of our inner selves.

Gathering also evokes thoughts from Homi K. Bhabha’s essay ‘DissemiNation’ in which he writes about the gathering of scattered people, converging, and sharing lived experiences to create a singular fact of historical importance. Similarly, this anthology is a gathering of women of colour’s voices scattered across Britain, coming together to write on nature, creating a record of their diverse reflections, and experiences. It is a powerful act of writing themselves into conversations on nature.

It felt important to include this many different perspectives, voices, and styles of writing to reflect the way that nature is made up of so many layers that come together or pull apart. We didn’t set out to achieve a conclusive, definitive, or an authoritative book on nature. We set out to provide an instigation, to evoke curiosity, and to explore. To be playful, celebratory and gentle at times, and at other times, angry, bold, and defiant. And rightly so.

Yet, despite these varying perspectives, there are a dozen or more essays that could have been included. We hope that Gathering is the beginning of a larger conversation; that people feel themselves reflected in these words, or feel inspired to write their own, and that more spaces are created for people of colour to express ourselves unapologetically and beautifully as the writers in this book have.

The writers showcased in Gathering open doors to understanding and shift paradigms. They dismantle barriers and challenge stereotypes, inspiring a more inclusive literary world where all voices can thrive and contribute to the collective narrative. They foster an environment of empathy and shared experience through their unique perspectives. Their words build bridges across cultures and communities, connecting readers from all walks of life. We hope that Gathering serves as a testament to the strength of personal storytelling in these challenging times, fosters meaningful connections and sparks profound conversations, so that we find ourselves renewed with hope for the future.

We invite readers to embark on this transformative journey with us, traverse the pages of this anthology, immerse in the visions painted by these writers, and feel the pulse of nature resonate within your heart. Let us gather to celebrate and remind ourselves that nature belongs to all, and that only through collective appreciation and understanding can we protect and nurture our precious planet.

– Durre Shahwar & Nasia Sarwar-Skuse

A British-Ghanaian in the West Country: On symbols, myths and reimagining the British Countryside

Louisa Adjoa Parker

For too long, there has been a commonly held perception of the British countryside, which often evokes images of green fields and cattle with heads bent to the grass, or villages with windy roads and quaint, thatched cottages. Some might think of tea in the afternoon: scones and jam and thick yellow cream. Or the sea, with its dancing pinpricks of light, and long stretches of shingle or sand. Or farms, mud, tractors, smells of manure, glimpses of rare birds. It is a place many Brits like to holiday in, and there tends to be a somewhat romanticised view of rural Britain. Whatever springs to mind, the British countryside has long been presented as a space which is inhabited by – and exists purely for – people who are white. Tucked within this image is the idea that rurality represents the past, an imagined Golden Age, a simpler era, untouched by the trappings of modernity (which includes all the immigrants who came with it). And yet, although at first glance it might appear that the British countryside is predominantly inhabited by white people (at least in comparison with urban areas), its history is intertwined with Empire, colonialism, and slavery. In fact, as many of us are beginning to realise, the very symbols we take to represent Englishness – tea and sugar and country estates – are rooted in this history.

Alongside this, racism is often considered an urban issue – it doesn’t exist in rural Britain because there aren’t any people to be racist to there, right? At least, that’s the pervading opinion that’s long been present: ‘there’s no problem here.’ Yet the idea that African, Asian, and other global majority heritage people are purely urban dwellers is a myth. Many global majority people who migrated to the UK settled in cities, yes, but not exclusively – we have multiple identities and we have inhabited multiple spaces, like anyone else. This idea that Black/Asian equals urban seeps into many areas of everyday life – from advertising to music to football to literature to TV and film. People within the Black British aesthetic, for instance, are often presented as one homogenous being, all trainers and/or nails, wearing the latest clothes, speaking in the same London-Caribbean hybrid slang (‘urban’ slash ‘street’). Here, I want to share my lived experience of being a Black woman of British-Ghanaian heritage in rural Britain, as well as exploring symbols of rurality and how we can make space for global majority voices within them.

My Black African father came from Accra, Ghana in the 1960s and married my white English mother from Reading. I was born in Yorkshire in 1972, which was a time of open, hostile racism in the UK; to be of mixed heritage was tough. Just before my thirteenth birthday, after my parents split up, I moved from Cambridgeshire with my mum and siblings to Paignton. South Devon was familiar – I’d been going to visit my English grandparents there since I was six. But the reality of living in a seaside town was different to being a visitor there – you see the rot under the veneer, the darkness that hides underneath the sunlit towns where people go for sun, sea, and sand. You soon learn the land itself is infused with racism, along with other ‘isms,’ and that for those viewed as outsiders, life can be hard.

Our new home was opposite bluebell woods. The first thing I noticed about Devon was that it was entirely white. There were no other brown-skinned people around, or if there were, I didn’t see any. The town I had left was surrounded by countryside, but it had been more multicultural. Here in Devon, other than my siblings, I was ‘the only one.’ And my difference did not go unnoticed by the local children. Most of the boys racially abused me and made it obvious they saw me as a female body to sexually experiment on, not as a ‘proper girl’ they’d be proud to be seen with. The girl next door was generally kind, although she merrily informed me that her dad hadn’t wanted ‘blacks’ living next door. He was, nevertheless, friendly enough when he got to know us. As far as I am aware, these kids – and their parents – had never seen a Black or brown person before, other than on the telly.

The land around me soon became my home, a second skin I inhabited. I explored the woods, climbing the steep paths strewn with rotting leaves. I walked our dog and played with my so-called friends, chucking firelighters into piles of leaves, trying my first cigarette, having my first kiss. As I got older, I found solace in the woods, and at times I’d take myself off to sit on a tree branch, watching the world go by. A mile away was Preston beach, with its terracotta sand and cliffs, where you could walk over the damp sand to Paignton, with its rusty pier and games arcades. I wasn’t a strong swimmer but enjoyed swimming in the shallow edges of the sea. In Totnes, where I went to school, there was the river Dart as well as woods and fields; spaces where I’d hang out with my friends, away from adult eyes. I took the land for granted the way young people tend to do – it was simply there. I didn’t appreciate its full beauty until I was older.

And yet the reality of being a Black/mixed teenage girl in these spaces was a strange, challenging, and often upsetting one. Although I’d grown up with racism, here it was supersized, like stepping back in time. My face looked wrong against this rural backdrop, this place of sea and green and palm trees. People like me, I was told, belonged in cities, and yet, here I was! What was I doing here? Where was I really from? Like many young people of mixed heritage, I struggled with my identity. An added layer for me was that of rurality. I had no role models in the countryside. I didn’t know what to wear, how to style my hair, I didn’t know how to be. So, like most teenagers, I wore the clothes my friends were wearing, tried, unsuccessfully, to style my hair like a white person’s. I wanted to be white and thin and have long straight hair. I hated being me. I escaped into a world where I was obsessed with boys (then men) who didn’t love me, as well as smoking, drinking and drugs.

When I was nineteen, I moved with my baby daughter over the Devon border into Dorset, to a small seaside town of Lyme Regis, famous for its fossils and literary connections. I went on to have two more daughters as a solo parent and wanted to bring my children up in what seemed like a safe space: low crime, white sand and gold-topped cliffs, a silvery light like no other in the sky above the bay. It was the 1990s now, and no-one wanted to be a racist. Yet in some ways it was safe, and in others it wasn’t. My daughters and I experienced daily microaggressions, comments about, and the touching of, our hair, racist jokes, and hearing inappropriate terminology and racism towards other ethnic groups. A friend once explained at length how she hated all the Asians coming to Britain.

‘What about the Raj?’ I said, ‘What Britain did to India? The famines?’

‘F**k me,’ she replied, ‘I don’t know anything about that! I was too busy chasing boys at school to learn anything.’

I bumped into the same friend years later in the supermarket she worked in, after I’d moved away. She started on about Brexit and how we had ‘too many immigrants.’

‘Mate, I’m the daughter of an African immigrant,’ I said, finally empowered by knowledge and the recent cultural shift in a collective understanding of race. ‘I think we’re going to have to agree to disagree on this one.’

My acceptance of myself and embracing my Black, rural identity has been a long journey. The turning point came when I was studying, and learned about Black British history, across the UK and in the countryside. I learned that we have been coming here for centuries, as – amongst other things – enslaved African ‘servants’, soldiers, sailors, entertainers, refugees, writers and abolitionists, and more recently, students, migrant workers, healthcare and catering workers. A fuller, reimagined history of rural spaces helps us all understand that we are connected, and that migration is not a contemporary phenomenon. It helped me to understand I have the right to belong. My journey also included working hard to undo the racism I’d internalised as a child, as well as researching and writing extensively about rural racism and diverse history in rural areas. Only now, in my fifty-first year, do I feel I fully belong in this space, and in my own skin. I am a Black woman of mixed heritage who lives in the countryside, and that’s okay.

My research also led me to understand what it is like for others, that people with African, Asian, and other global majority heritage experience racism, which ranges from microaggressions to verbal and physical assaults. Although we are individuals, with different backgrounds and protective factors in place, there are many commonalities. Most of us witness and/or experience racism, to some degree. Many of us feel isolated without others who share our ethnic heritage. We are both highly visible – we stand out, and can’t ‘blend in’ – and invisible, when it comes to being heard and represented.

There is so much power in representation. The first time I saw an image of a Black woman in the countryside was like finding a nugget of gold. The photo, in which the woman, in white jacket and boots, headwrap, camera in her lap, her head turned away from the camera, was part of a series called Pastoral Interlude by the photographer Ingrid Pollard. It was beautiful, and it subverted the idea of who belonged in the countryside, opening the doors for people like me.

Another pivotal moment was reading the poem ‘In My Country’ by Jackie Kay. I related so much to her poetics of walking in the countryside as a Black woman, I felt I had been seen – here was someone who knew, who got it.

There have been several changes in recent years when it comes to conversations around ‘race’ and ethnicity in rural spaces. There has been a shift in the demographics in the countryside over the past couple of decades. In the southwest where I live, there has been a visible increase in the numbers of global majority people living in and visiting the region. As well as this, since the murder of George Floyd and spread of the Black Lives Matter movement, there has been a shift in local organisations’ understanding of racism and a clear desire to do more (or at the very least, to be seen to be doing more). There has also been increased interest in who is accessing the countryside with a focus on ‘race’ and class, and a shift in the ways we tell the histories of rural spaces; all part of a wider, global movement to decolonise our education systems, public spaces, as well as hearts and minds. Decolonisation can be a contentious issue, with some rejecting the need for it at all, and others disagreeing on the best way it should be done. I understand that for some, there is a real fear that our national identity and heritage may be lost, replaced with the unfamiliar, strange and ‘woke.’ Yet for me, it can only be a good thing – undoing the wrongs of the past, making space for diverse stories to be told, telling the stories of both colonisers and the colonised, and in doing so, shining a light on the long, dark shadow of Empire.

At the time of writing, I have been thinking about symbols of rurality, who they represent, and how these can be widened out to include ethnically diverse people. Recently, I went to meet with Professor Corrine Fowler, author of Green Unpleasant Land, to talk to her for her forthcoming book. As I drove through the village of Tolpuddle, where we were meeting to walk and talk, I reflected on how going to strange villages has never felt safe. I found myself scanning my surroundings as I drove, and noticed a Black binman, chatting and laughing with a white person. It must be okay here, I thought, irrationally. But as I drove past the St George’s flags and houses, I started thinking more about the symbols of rural village life and who and what they represent.

‘I’ve never seen a Black woman driving a tractor,’ I said to Corrine, as we walked through the Dorset countryside. ‘Or any woman, for that matter. It’s usually young white men.’ And there are spaces within villages that feel particularly unsafe. I won’t, for example, walk into a country pub alone. That moment when the room goes silent, and people’s heads swivel as one towards you feels too much to bear. Where are you from? they seem to say, and what are you doing in our pub?

Another symbol of country living which cuts across class: ‘Hunting-shooting-fishing,’ I said to Corrine as we watched men in waders cast their lines into the river. ‘I’m a vegetarian! I don’t do any of that sh*t.’

She laughed. ‘I’d never heard them all put together like that.’

I talked to my husband about symbols when we went to the small seaside town of West Bay in Dorset recently. We looked around an antique centre, and I spotted a number of black figurines and masks which were parodies of Black people from the past. I braced myself, as I tend to do, for golliwogs, which are often to be found in shops and pubs in the countryside. For people like me, who grew up facing an ugly parody of myself grinning eerily from the marmalade jar over my breakfast, they are a symbol of hate and dehumanisation.

‘But you can’t get rid of the symbols,’ my husband said. ‘They’re part of what makes the countryside.’

‘I’m not saying we should get rid of them,’ I replied, ‘but open them up to include more people. Where are the images of Black families having a cream tea? Or doing outdoor activities? Where are the images of Black or Asian women with mud under their fingernails?’

‘Like yours,’ he said.

‘Exactly!’ I love gardening without gloves, digging my bare hands into the earth, in spite of the mud left under my fingernails afterwards. My nails, it has to be said, are definitely not ‘on point.’

And the biggest, most prominent symbol of all: the country house and estate. Much work has uncovered links between these places and our colonial past, and we are learning what is hidden behind these walls, what might be buried in the grounds of manor houses. It is uncomfortable for some but imagine how uncomfortable it feels for people like me, who have known the history for some time. Here is a place I do see myself reflected, but most often, as a victim.

There are various campaigns, currently, to increase access to the countryside, to make space for a range of people, and for global majority people to reconnect with nature and the land. And yet there is still much to be done – simply having larger numbers of African and Asian diaspora people in the countryside is not enough. We need, as a community, to change the infrastructure, ensure everyone’s needs are met, fully understand the history, ensure global majority people can see ourselves reflected in the landscape, and challenge racism and other forms of discrimination in all their guises.

In the countryside, already complex issues of identity and ‘race’ have further layers of complexity. Many from the wider white rural community often have little face-to-face interaction with people from ethnic backgrounds different to their own. But we live in the twenty-first century. The internet exists and there’s a wealth of information out there. It’s easier than ever before to learn about colonial legacies and ‘race’ and the experiences of those who have been marginalised and ‘Othered.’ It is possible and easy to learn beyond your own experience.

We need to dismantle myths and stereotypes and find ways to represent the full breadth of human beings in ways that are authentic. As well as this, people from the wider, white British community can act as allies to those of us who have been racialised as ‘Other’. The beautiful rolling hills and coastlines are for all of us. Together, we can reimagine the British countryside (and all it represents) and make space so that everyone is welcomed.

Nature is Queer: We Could Learn a Thing or Two from That

Jasmine Isa Qureshi

I am a biologist. Well, I’m a failed biologist. I didn’t enjoy academia and the symmetrical balance we as students were forced to teeter upon to reach an ending that I saw as just being the beginning again, but with a different flavoured topping.

Biology to me is magic. It is Sorcery. Squishy, living, breathing, toxic, untameable, nonsensical, dribbling, all-powerful magic. By magic, I am suggesting the abstract concept and title of ‘magic’ as pertaining to beauty, and ‘chaotic’ behavioural observation (chaos theory), chemistry – a science often referred to as ‘magical’ due to its explanation of natural processes in terms we cannot directly sense, and spontaneous reaction. I am suggesting that biology is an art of exploration. The art of asking questions, and the art of finding out.

Words such as ‘magic’, and ‘art’ are normally personifications of more emotionally charged subjects, such as literature, and music. However, these terms can and should be used for science-based subjects too, especially biology and ecology, thus closing the gap between ‘creative’ subjects, and seemingly ‘non-creative, fact-based’ subjects.

This gap ignores the intersectional and interwoven discrepancies that exist in all subjects and concepts. It limits the flexibility of perspectives that are needed to progress our understanding. Unlearning the bias of ‘emotionless’, and linear/binary science theory and study, helps us to collate the natural world into magic and art, and promotes a more ‘passion-based’ approach (which also seeks to topple false hierarchies, the viewing of nature as a simple ‘resource’, and promotes respect of the natural world, and by extension, the rest of the world).

Furthermore, this flexible, more creative approach, also allows gatekeeping to be disintegrated, and elitist methods of teaching and accessing resources around these subjects to be disallowed. Nomenclature – and its usage as a key factor of identification – may be a small part of what we see, and perhaps rudimental, but its influence cannot be ignored. It often acts as an obstacle to those without the specific experience or background to access its pre-empted concepts.

To me, biology, and indeed the behaviour of the natural world is the music produced by the alchemy of existence. Music must be studied with care and attention. The overall passion, flexible mindset, creative flair and love a musician has will be the deciding factor in the quality of music. The same is true for a biologist. For example, as an ecologist and someone with a specific love for entomology and invertebrates, if I am to study an animal in this environment, I must approach this study from an angle with as little anthropocentric bias as possible, because viewing wildlife with ‘human characteristics’ can cause entire conclusions to be drawn upon false pretences.