Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

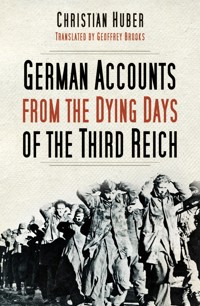

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

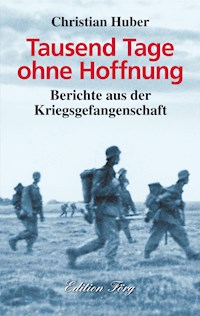

Unlike other historical depictions of the fall of the Third Reich, German Accounts from the Dying Days of the Third Reich presents the authentic voices of those German soldiers who fought on the front line. Throughout we are witness to the kind of bravery, ingenuity and, ultimately, fear that we are so familiar with from the many Allied accounts of this time. Their sense of confusion and terror is palpable as Nazi Germany finally collapses in May 1945, with soldiers fleeing to the American victors instead of the Russians in the hope of obtaining better treatments as a prisoner of war. This collection of first-hand accounts include the stories of German soldiers fighting the Red Army on the Eastern Front; of Horst Messer, who served on the last East Prussian panzer tank but was captured and spent four years in Russian captivity at Riga; of Hans Obermeier, who recounts his capture on the Czech front and escape from Siberia; and a moving account of an anonymous Wehrmacht soldier in Slovakia given orders to execute Russian prisoners.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 252

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Note: Whereas the military events correspond to the historical record, some of the persons mentioned herein have been given an alias to protect their identity.

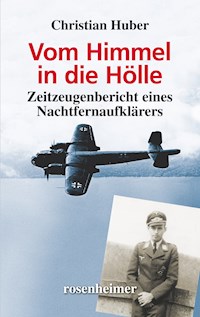

Original German language edition titled Das Ende vor Augen, first published by Rosenheimer in 2012

© 2012 Rosenheimer Verlaghaus GmbH & Co. KG, Rosenheim, Germany

First published in English 2016

This paperback edition published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Christian Huber, 2012

English edition © The History Press, 2016, 2022

Translation © Geoffrey Brooks, 2016, 2022

The right of Christian Huber to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 6918 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction by Roger Moorhouse

Prologue

1 Summer Night: Peter Stuffer, Obergefreiter, from Ruhpolding, Eastern Front, Army Group South

2 Hunted Down: Hans Klinger, Waffen-SS NCO, Eastern Front, Army Group South (Wasserburg)

3 Why We Were Fighting: Anonymous Paratrooper NCO Eastern Front, Army Group North

4 From the Ski Slopes to Siberia: Hans Obermeier, NCO, Eastern Front, Army Group Centre, Born Rosenheim 1925

5 Home and Yet Betrayed: Helmut Haubner, Sergeant, from Schnaitsee Bavaria, 1945

6 The Last Panzers at Libau: Horst Messer, Corporal, Eastern Front, Army Group North, from Bad Feilnbach

7 War Voyages on the Rhine: Joseph Rass, Senior NCO, Western Front, from Kolbermoor

8 Forester in Hell: Karl Hubner, Hermann Göring Regiment Driver/Flak-Gunner, Eastern Front, Army Group Centre, From Amberg

9 The Old Man of Gömörnanas: Memories of an Unknown Soldier, Eastern Front, Army Group South

10 Cemeteries: Gerd Rube, Second Lieutenant from Rimsting, Final Battle for Berlin

Introductionby Roger Moorhouse

The bloody demise of the Third Reich – the famed Götterdämmerung, the ‘Twilight of the Gods’ – has been much explored in recent years. A number of English-language history books have sought to reconstruct the final days of Hitler’s odious Reich, with varying results. But, in the vast majority of examples, one voice is crucially absent: that of the defeated German military.

This is a curious omission. It may be, of course, that many English-language historians lack the language skills to incorporate primary sources in German, or one might assume that there is some disinclination to include German military accounts, maybe for fear of arousing sympathy for the defeated enemy. But, the real reason lies with Germany’s curious process of ‘coming to terms’ with its past, Vergangenheitsbewältigung, in which the national mantra of contrition and collective guilt has effectively silenced the voices of veterans – many of them entirely blameless – who might otherwise have found publication. It is interesting that it is only in the last decade or so that the accounts of ordinary German soldiers have found an audience in Germany at all.

All of which should serve to explain why this book is so important. Journalist Christian Huber has spent years collecting and editing the personal accounts of German veterans from southern Bavaria. The selection presented here is only a part of that collection; a total of only ten accounts, it is but a drop in the ocean of German memory, but it nonetheless has significant breadth, with contributions from members of the Wehrmacht, Waffen-SS and Luftwaffe ground forces.

There is also a good geographical and chronological spread. One contributor, for instance, provides a fascinating account of waiting on the banks of the River Bug in occupied Poland in June 1941 for the order to invade Stalin’s Soviet Union. Another tells the story of a bloody engagement with Yugoslav partisans in Bosnia in 1943.

The contributions surrounding events at the end of the war are similarly rich and varied. One describes being captured by the Soviets in the ruins of Königsberg; another found himself in hostile Czechoslovakia; a third escaped the ‘Heiligenbeil Cauldron’ in East Prussia, only to be thrust back into the Battle for Berlin. For all of them, the imperative was to head west: to surrender to the Americans and thereby avoid the grim fate that awaited them at Soviet hands – a sojourn of hard labour in Siberia.

The range of emotions on display are also interesting. For many, the war – by its close – appears almost to have taken on a life of its own. It had become something like a force of nature, something that had to be endured, and survived, but over which the individual could exert no influence at all. In addition, very few of the soldiers seem to have had the wherewithal and the mental strength to escape their fate – the Waffen-SS man being one exception.

In all, despite its relative brevity and its small sample size, this is a book with much wider horizons than the reader might at first suspect. It gives a taste of the German military’s view of the dying days of the war: the desperation, the resignation and the fear. As such it makes a genuine contribution to our understanding of a crucial and highly dramatic period.

Even if the political will existed to carry it out, it is probably too late now for a concerted oral history programme in Germany to record the memories of war veterans for posterity and for the benefit of historians. Nonetheless, for all their limitations, books such as this one are a welcome start along that road. They allow us a glimpse of a world of memory that has been neglected for too long and is now fast disappearing. For that they should be welcomed.

Roger Moorhouse2016

Prologue

‘And suddenly we are consumed by a fear that we have come too far ever to see the homeland again.’ What words could better describe the morale of the German soldier in the last few months of the Second World War than these by Bertolt Brecht? Fears for one’s family – the bomber war had long reached out to even the smallest towns – fears for one’s own life, fears about the impending defeat and an uncertain future: especially in the final and most bloody phase of the war, German soldiers were forced to shoulder an inhuman load. The end before their eyes, not one could know what the morrow would bring.

Over the years, the author contacted numerous former participants from southern Bavaria. From these meetings many friendships evolved. In long talks, German soldiers provided their very personal memories of the end of the war, made diaries and manuscripts available. From these sources ten differing stories bring the reader closer to the horror of it all.

1

Summer Night

Peter Stuffer, Obergefreiter1, from Ruhpolding, Eastern Front, Army Group South

June 1941. I remember it all as if it were yesterday. We had been on this bank of the Bug River for days. Faces bronzed, dust between the teeth. We were Franz Schenkenbach, known as ‘a Prussian thoroughbred’ because he knew no Bavarian dialect and couldn’t understand our jokes; little Hans Reichl from Raubling/Inntal, Georg ‘Schorsch’ Kramer from Hundham/Oberland, called ‘the Professor’ for his wire-rimmed spectacles; Gerd Ziefer, a great oak of a man. Also Auer, Unterhuber, Loferer, Meitinger, Bader, Rampfl, Baier, 120 others and myself.

We had plenty to eat and often would take long naps during the midday heat after gorging ourselves from tins. We slept sitting, standing and even walking, water bottle in hand. Little Hans Reichl was on watch leaning against a tree, rifle over his shoulder, his steel helmet pushed forward to cover his face. He was having forty winks when his knees buckled. He had fallen asleep in broad daylight. The muzzle of his carbine went through his upper lip and struck his front incisors. The first man of our company to be wounded on this bank of the Bug River. After a couple of days it had healed enough for him to lie alongside us in the trench. Bad luck for him, as we were were to find out.

The Bug River: we could see it from our trenches. Our bank of the river was slightly elevated. Despite the broiling sun and the river nearby we were forbidden to bathe. ‘We are not here on a pleasure cruise,’ the sergeant said. We thought it was for reasons of military discipline and because the sergeant, Hemmberger from Swabia, didn’t want us to enjoy ourselves. Not until later did we learn that it was because of noise. Noise was what was needed least of all. Over there were the Russians – actually our allies then. Our company had marched across Poland, a real joy. We hardly ever saw the Polish enemy, only the clouds of dust they threw up in their retreats, and here at the Bug we met up with our ally, Ivan. That was almost two years ago now, in late 1939, and meanwhile we had had the experience of the French campaign in which we marched a lot but luckily were not asked to do much in the way of fighting.

We saw nothing of our current ally, the Russians, but instead swarms of mosquitos paid us a visit from the river morning and night. We would learn to fear this soft, high-pitched hum in quite another connection later. Our heads were empty and hollow. The photos of our loved ones at home were our mainstay. We could easily all be on holiday were it not for the questions which circulated amongst us, which tormented us, which for days would keep us awake at night. Where next? That was the most important of our questions.

‘The Russians will let us drive through to Persia, then we can get at Tommy through the back door,’ Schenkenbach laughed. Quite a few of us believed that the Russians would let us pull out for Africa, where Rommel was bringing the British to account with his Afrika Korps. At least we kept this particular hope alive. Or maybe Stalin had sold the Ukraine to Hitler? What else might it be that lay before us? Many of our generals had served in the Great War. They would not be so stupid as to begin a war on two fronts, we thought. Britain was far from defeated, even despite the battering it was suffering at the hands of the Luftwaffe. How bloody the reprisals would be was unknown to us on that 21st day of June 1941 on the steep bank of the Bug.

The heat of the afternoon was intolerable. To our surprise we received a supplement to our rations. One bottle of schnapps between four of us, and cigarettes. Marching rations for three days. Marching? To where? We had no idea that we were just a field-grey crowd of pieces on a giant chessboard, that fate had tossed us on this riverside and would soon put us harshly to the test. We were mountain troops: 2nd Company Gebirgsjäger 98th Regiment. From Lenggries, fate had taken us through Dukla in Poland to the Loire, back to the Swiss border and now finally to the Bug in Poland. And here we waited.

Most of us dozed until night came. We knew there was something different about today. Our lieutenant, Sepp Kerner, a cheerful, lanky type from Mittenwald, told us meaningfully at noon, ‘There is something in the wind,’ and to back this up the senior officiers, whom we hardly ever saw, came down in hordes directly to the river bank where they put their heads together. Secret discussions. In a couple of hours we would all know. Our sergeant advised us that until then we should get some shut-eye, but today we thought even less of sleeping than we had done in the short, hot nights preceding. Towards midnight lorries came up to our camp from the rear. In the bright moonlight we saw the rubber dinghies being carried at the back. A pioneer battalion. Slowly it dawned on us what this portended. Our thoughts swept homewards. A mood of depression spread. Although everybody had long been awake, hardly anyone spoke aloud. There was some whispering to be heard until our group leaders chased us out of the field camp. At 3 a.m. it was the end of the secret discussions. In a clearing in the middle of a gloomy wood, our platoon leader Kerner faced us, a pocket lamp dangling from his breast. White light. If it turned green, it would be too late for the world. Kerner read out the proclamation that would hurl us towards ruin. ‘Soldiers of the Eastern Front …’

Eastern Front? Despite the clammy heat the blood froze in our veins:

Soldiers of the Eastern Front! At this moment we are about to embark upon an advance, the like of which in extent and scale is unknown in history. United with Finnish comrades the victors of Narvik stand at the Polar Sea in the North. German divisions under the command of the conquerors of Norway are protecting Finnish soil shoulder to shoulder with the Finnish freedom fighters under their Marshall. The formations of the German Eastern Front stretch from East Prussia to the Carpathian mountains. On the banks of the Pruth, on the lower course of the Danube to the shores of the Black Sea, German and Romanian soldiers stand together under Head of State Antonescu. The purpose of this front is therefore no longer to protect individual countries, but to safeguard Europe and with it save all. Soldiers of the Eastern Front, you are called forward today to render this protection.

A war on two fronts. Within the hour we would cross the Bug with our pioneers. Already we could hear huge swarms of aircraft heading to the east. The humming overhead would last for hours. At any moment in this hour of destiny we expected to hear the artillery spewing forth into the night sky. The light of the pocket lamp at the breast of our platoon leader turned from white to green. The signal for us to board the dinghies. At that moment the war made its first shout, peace breathed its last. The attack on the Soviet Union began.

Three and a half years later my regiment had practically ceased to exist. Most of my comrades of the early days of the attack were already long dead. We had had the bad luck to become involved in the heaviest fighting straight away in the border region. No more marching to the sound of ‘Hurra!’; no longer a stroll as it had been in Poland. The Russians were of another calibre. From the first day onwards we tasted war on our lips. On the very first night we had our first dead and over thirty wounded. And so it would go on and on, almost every day, until our world went under.

I saw Reichl die when he threw himself on a hand grenade which one of the reserves, a man disliked by all, rolled intentionally into the trench. Reichl was first to see the danger, and threw his body on the grenade just as it exploded. His ribcage rose just a little, then he stretched out his limbs. He died at once. It was the first time that I was unable to bury a fallen comrade, for the Russians never gave us time for it. The sight of Reichl’s body tore my heart out and for the first time ever I burst into tears. That was two years ago in the fighting for Mount Semashko on the Black Sea. Almost every night I still see the dead Reichl, whose body saved our lives.

Not long afterwards ‘the Professor’, Kramer-Schorsch, came off particularly badly. South of Belgrade our regiment was encircled by the Soviets. We were in infantry trenches in a small wood. Luckily we had had a couple of hours to dig in deep before the Russians began to hammer our lines with everything they had. They were firing shells which exploded 1 or 2m above the ground and had a fearsome splinter effect. These shells reduced the little wood to tinder. Splinters whirred above our heads. A couple of metres away I heard a hell of a loud bang which burst my right eardrum. I ran to the impact point. The remains of a man had been hurled against a tree, torn to shreds and unrecognisable. When I asked who it was, I was told that it was Corporal Langhans. At home he had waiting for him a mother and a young fiancée. I had no time for reflection, it was crashing and banging wildly all around us. Fire was concentrated on our position; it was too late to run for it. Between the shell hits I heard shouts for help and groaning from the other end of the little wood. I knew the voice: the Professor. When the firing began to ease off a little I advanced cautiously towards the direction from where I kept hearing the cries. The infantry trench in which the Professor and Huber Eight were lying had been turned into a single shell crater.2 Both had been terribly wounded. The shell had taken off Huber’s legs. When I spoke to him he did not react. He was a stocky man, reliable and calm. I liked him a lot. I stroked his hands, he grew quieter, gave one last breath and then didn’t move again. One footstep away lay Kramer-Schorsch, the Professor. His wire-rimmed spectacles had been torn away by the air pressure of the explosion. Despite the dusk I saw that the explosion had taken off the lower half of his body. He was still alive, gabbling and tugging at the straps of his field pack. I helped him out and laid him flat on the ground. I stroked his lower arm. He noticed that somebody was caring for him and grew quieter. The next time I spoke to him there was no reaction. Carefully I broke off the lower half of the ID tags of both men and left quickly. That was a bad night. The Soviets kept at it. It was as well for me that they did, for otherwise I would have dwelt on the horrors I had seen.

I don’t know why I am remembering Reichl and Kramer right now. Perhaps because they were such cutting experiences for me. Death on the battlefield is often an anonymous death. We had to simply leave our fallen where they lay. Especially in winter, when the ground would be too hard for the spade. Snow and ice make for a temporary grave; the thaw in the spring releases the bodies again. The most horrific months in the East are April and May, I thought to myself, and found comfort in being so close to home and not having to cross over corpses.

Reichl and Kramer were history, and I never saw again the remnants of my company, my platoon, or my group at the Bug River. Repeatedly in those last months of the war I had the misfortune to be obliged to join a variety of units directly from further training, convalescent leave or from the thick of a fight. It was a bitter experience because one never knew where one’s own comrades,3 the soldiers one knew, had gone. In strange units one felt helpless until the first firefight, until someone relied on you and they knew that you were reliable. I have seen soldiers shattered at not being able to return to their own unit after leave or being wounded. In the closing months of the war it was frequently the case, and I was no exception. I cannot even give a clear account of how I finished up here near Posen. For days I had been marching at the trot towards the West amidst a mob which was not my own. The Eastern Front no longer existed. Our march was more like taking flight. Fortunately we had a first-class captain, a Rhinelander, leading our alarm unit of forty men. I do not recall his name. Whenever we were called upon to resist a Soviet advance, he always took great care to ensure that we had a decent position, that we dug trenches in such a way as to offer the greatest fire power with our few weapons. In reality we were capable only of slowing down the advance of the Soviet spearheads for a short while; he knew this as well as we did.

That morning at the end of January 1945 we came to a halt between Posen and Schneidemühl at a place which I think was called Waitze. It was at a fork in the road. Some regimental commander or other, the chief of an interception staff or a battalion commander had decided that this fork was important. Therefore we turned back, had a look over it for a couple of hours and stopped our retreat. We set up our heavy MGs [machine guns] in two farmhouses. We still had a couple of hundred rounds; God only knows where the captain got them from. The rest of us were on a small hill. The captain picked four reserves as he had been trained to do. We almost laughed when he ordered them to fall back and hold themselves in readiness for ‘an emergency’. The whole Wehrmacht was an emergency. And what would these four men be able to pull off against Russian tanks?

We had only just finished digging in when we heard the noises of war rolling towards us. What would our mob be able to achieve without panzers, without heavier weapons than MGs? Then the first columns came down the road towards where the road forked. At the last moment the captain cried out, ‘They are not Russians! Don’t shoot!’ Waltzing towards us came an indescribable collection of humanity, oxen, heavy farm horses and half-starved cattle. Hundreds of women, old people and children on wooden carts, on foot, dressed in rags and tatters, apparently with the last of their belongings. There were horse-drawn waggons, perambulators and hand carts. Women carried crying babies in their arms, very ill children lay on plank-beds drawn by gaunt horses. It was difficult to say which would die first, the people or the cattle.

These refugees from Schneidemühl and Posen all gathered suddenly at this godforsaken fork in the road, and although we were expecting the Russians to appear at any moment, we crept out of our holes, let the people see who we were and caught a glimpse of a smile here and there. Our field-grey mob with a couple of machine pistols and a captain who looked experienced apparently won their trust. We made them feel safer. Swiftly the captain sorted out the entanglement of waggons, animals and people. There was a big release of pent-up emotions but finally they formed into orderly lines.

‘A huge mess,’ said one of my companions, a stranger to me as yet.

‘It looks very bad. But the Russian fliers don’t like it when it’s sunny.’ We looked up to the sky and prayed that it would remain so.

We struck up conversations with the refugees. They described how they were forced out. Two days ago Nazi Party functionaries had turned up in every small village and ordered the inhabitants to make their way westwards because the Russians were approaching. Many had less than twenty-four hours to pack up their belongings. Many farmers preferred to remain where they were but the SS and police insisted that they leave. Nearly all of them had to abandon their cattle. A few tied a cow to their waggon – fresh milk for the road. Many of the refugees were grouped in families or with neighbours from their hamlets. Dying or even dead family members were not left behind.

The columns were averse to setting off for the next few hours. For reasons best known to themselves, the Russians were not interested in this swarm of bodies. Towards evening the artillery fire grew less. Refugees reported that some of them had never even seen a Russian. At dusk, when the trek resumed, our captain sent a patrol off to the East: ‘Have a look at what’s up back there.’ When the three men returned at midnight, they reported abandoned villages and farms, animals in distress in their stalls and in the fields. It was as if humanity had died out.

We had only a couple more hours’ peace. Before first light the sky was lit by gun flashes. As usual when they decided to advance, the Russians began with a massive artillery barrage. We had tremendous luck. The two farmhouses in our vicinity and our mob only came under fire from a couple of mortars while everywhere in our surroundings the earth was churned by Stalin’s organs [katyusha rocket launchers] and heavy shellfire.

We knew what was coming, and I knew that we wouldn’t be able to hold off the Russians for more than ten minutes. While it was still dark I had got to see the inadequacy of our defensive line. The farmers had made us hot soup, and I took some to each trench I could find. To the left and right of us were a couple of infantrymen in holes like ours, to our left behind us were some Volkssturm, small groups of old men and schoolboys. Many wore Reichspost or Reichsbahn uniforms, others had a Wehrmacht greatcoat over civilian clothing. Some of them were armed with old sporting guns. These were the miracle weapons that our glorious army leadership had promised us.

Then the Soviet artillery fire ceased, the mortar range lengthened, and the bombs passed above our heads. Whenever the Russians attacked, these were the eeriest minutes. I break out in a cold sweat even today when I think of it. Then I saw them and I caught my breath. Hundreds, no thousands of Russians were heading for our small position with wild Hurrahs! Our MGs gunned down the frontal assault of the first rank, but the second and third ranks kept coming. Soon we began to run short of ammunition. The Russian anti-tank guns took out our two MGs with direct hits, having had plenty of time to take aim. We had nothing more to offer and now the Russians were at our trenches and we were simply overrun to the left and right of us. As I fired at the Russians nearest me with my machine pistol, I felt a stabbing pain in my shoulder. It hurt so much that I almost fell unconscious and dropped my weapon. It felt like a large shell splinter had penetrated my upper arm. It wasn’t bleeding much but the pain was so intolerable that I lost consciousness for a while.

When next I opened my eyes I found myself in the Waitze schoolhouse. A paramedic was standing near me, looking at my wound as if mystified. ‘It’s not bad,’ he stammered, but I knew better. A splinter from a phosphorus shell had got into the flesh of my arm, and was quietly burning its way ever deeper down towards the bone. I hope I’m not going to lose my arm, I thought, as I saw some Russians standing at the door. They treated our wounded in the school correctly. Whoever was able had to undress to his underwear. The Russians went through our things closely. We got some of the clothing back but naturally they retained our boots and anything of value. Later a Russian doctor appeared and treated the worst cases. He took care of my own wound apparently he knew what had to be done. I lost consciousness again for some hours and then found myself in a Russian lorry heading eastwards. After four and a half years fighting, the same period of time awaited me in captivity. Siberia. But the Russian doctor saved my arm.

__________________

1Obergefreiter is equivalent to a British lance corporal, but without NCO (Non-Commissioned Officer) status.

2 Men with the Bavarian surnames Huber and Meier were so numerous that each was given a number as a suffix to his name for identification purposes.

3 ‘Comrade’ was not a political term; German soldiers used it to indicate a man who had seen action at the front.

2

Hunted Down

Hans Klinger, Waffen-SS NCO, Eastern Front, Army Group South (Wasserburg)

What was to become of us? We had become seized by doubt. We were nervous, excitable. For weeks we had been fighting a much more powerful enemy, had sustained heavy losses and rushed from one setback to another. The signs of the final collapse were unmistakable. We had been on the Danube near Vienna since the previous day. We were ready. My motorcycle platoon had dug in again; in a small wood we parked the few armoured scout cars we still had. They meant everything to us. They kept us alive, were our insurance. They gave us the chance to withdraw from dangerous situations, like the one we were in right now. I kept a nervous, constant watch on the other bank of the Danube through binoculars. Ivan was already nestling there, bringing up mortars and guns. Two T-34s were feeling their way cautiously towards the bridge. More and more tanks. Beforehand, when we were on the other bank of the Danube ourselves, we destroyed a number of them. What use had that served? They just kept on coming as though they were multiplying at will, ugly creatures of fable which crushed everything: defensive positions, the power to resist. Even fighting morale began to fade beneath their murderous tracks.