Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Origin

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

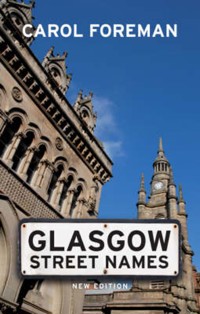

There is a story in the name of almost every street and district in Glasgow, with some tracing their origins to pagan times, long before Glasgow could even be called a city. In this hugely informative and entertaining book, Carol Foreman not only investigates the influences and inspirations for many of the city's most famous thoroughfares, but also considers the origins of particular districts, buildings and even the great River Clyde itself. This revised edition includes new information on city-centre street names from the M8 to the north bank of the Clyde, to Glasgow Green and Bridgeton in the east and to Kingston Bridge in the west. Also included are the districts of the Gorbals, the West End and Anderston. Packed with fascinating information and enhanced with over a hundred photographs and drawings, Glasgow Street Names is an indispensable book which introduces the history of the city in an imaginative and accessible way.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 248

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GLASGOW STREET NAMES

GLASGOW STREET NAMES

Carol Foreman

This edition first published in 2007 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published as Street Names of the City of Glasgowby John Donald Publishers, Edinburgh, in 1997

Copyright © Carol Foreman 1997, 2007

The moral right of Carol Foreman to beidentified as the author of this work has beenasserted by her in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publicationmay be reproduced, stored or transmitted inany form without the express writtenpermission of the publisher.

ISBN13: 978 1 78885 270 8

ISBN10: 1 84158 588 2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is availablefrom the British Library

Design and typeset by Mark Blackadder

Printed and bound in Great Britain byThe Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, Wiltshire

CONTENTS

Rough plan of the streets of old Glasgow

Introduction

The street names

Index

ROUGH PLAN OF THE STREETS OF OLD GLASGOW

INTRODUCTION

Most people have thought at one time or another ‘I wonder how that street got its name?’. When trying to research Glasgow’s streets, I discovered that nothing had been written about them since 1901. When the first issue of the book appeared, it was the first reference work of its kind to be published since 1901 when Hugh MacIntosh produced The Origin and History of Glasgow Streets. I decided to set this oversight to rights and began compiling Street Names of the City of Glasgow. I say ‘some’, as it is impossible within the limits of a single volume to detail them all – it would probably be a lifetime’s work.

In my first edition of the Street Names of the City of Glasgow (this publication is the second), I chose an area to work within, concentrating particularly on the City Centre, to the north the M8, to the south, the north bank of the River Clyde, east to Glasgow Green and Bridgeton, and west to the Kingston Bridge. For the second edition of Glasgow Street Names, I have added the Gorbals, Anderston, and the West End of the city to my original parameters.

This book is neither a street directory nor an architectural guide, although particular buildings and monuments of note have been included. Some streets have been missed out, their names being self-explanatory, some were ignored because they were named after worthy but uninteresting people. Other streets defied my powers of research. I simply could not discover how they got their names. Many names are nothing more than signposts today but have been included because they are tied to the ancient history of Glasgow and should not be lost in the mists of time. I hope you will forgive me if your favourite street has been omitted.

As streets derive their names from a variety of sources that often indicate the date they were laid out – local associations, sentiment, royalty, distinguished persons, historical events etc., there is a story in the name of almost every street and district in Glasgow. Some of them bear names bestowed on them in Pagan times, before there was a city of Glasgow.

As well as the origin of street names, included are those of the River Clyde and the Molendinar burn, plus those of monuments and areas with unusual names. The origins of districts such as Cowcaddens, Gorbals and Polmadie are also given. There is also a section headed Royalty that collectively describes many of the streets named after various members of Britain’s past royalty.

During my research, I wore out much shoe leather tramping round Glasgow and all the information about the condition of buildings or the existence of streets was, to the best of my knowledge, correct at the time of publication. However, in a city things change all the time – buildings that have lain derelict for years are restored to their former glory, others are demolished, new streets appear and old ones vanish. I would also like to explain that some buildings no longer have their original numbers. Therefore, when I mention that a certain establishment was at No.‘X’ in a particular street a century ago, although the building still stands, it may have a different address today.

As a number of street names have conflicting explanations as to their origin, it is possible that many of you will find some that differ from those given. If so, I would not be averse to hearing what they are. Also, if any glaring errors have been made, please excuse them. I did not intend for the book to become a mini-history of Glasgow but as I delved into the past and fact after fact on every aspect of the city became known, that is what this book became. After all, people and events make a street, not just buildings.

Carol ForemanGlasgow, 2007

THE STREET NAMES

ABBOTSFORD PLACE, Gorbals

Originally called Laurie Street by James Laurie who, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, laid out the prestigious new suburb of Laurieston in the Gorbals. Later Laurie Street was renamed Abbotsford Place after the home of Sir Walter Scott in Roxburghshire. As Laurie had spent part of his life among high society in London, he named many of his streets after the lands and titles of members of the nobility.

The tenements built in Abbotsford Place were spacious, many having seven rooms, and were favoured by professionals such as doctors. They had Italianate Renaissance frontages and traditional Scottish circular stair-towers at the back. Abbotsford Place also boasted Georgian-style terraces. If the buildings in Abbotsford Place had survived for just a few years after the destruction of the area in the early 1970s, they would probably have been protected within a conservation area. Remaining is the former Abbotsford Primary School at the corner of Abbotsford Place and Devon Street, built in 1879 to an Italianate-style design by H.&D. Barclay. The carved heads above the doors, both front and back, are of eminent Scots. On the Devon Street frontage, the heads represent John Knox and David Livingstone. The school had a large central hall surrounded by classrooms, with a balcony overhead allowing classrooms at first floor level.

ABERCROMBY STREET, Calton

In early times, the road east from the city ran from the Drygate to Ladywell Street, over the Gallowmuir, along the Witch Loan to Barrowfield and the Dalmarnock Ford where the Clyde was crossed. Old maps clearly show Witch Loan (said to have been created by the masons who built the Cathedral and lived in Rutherglen), part of which was north and part south of Gallowgate. The southern part was named Abercromby Street (1802) in honour of Sir Ralph Abercromby, a distinguished British general mortally wounded at Aboukir during the Battle of the Nile in the war for Egypt against Napoleon. The section of Abercromby Street that meets London Road was originally called Clyde Street after local brewer John Clyde.

Sir Ralph Abercromby

The northern part of Witch Loan became Bellgrove, ‘bel’ signifying a prominence in the old Scots language, or ‘belle’ for beautiful in French. Bellgrove was once a narrow road with a row of trees down each side and a small ditch running from Duke Street to Gallowgate. On the east, at the top, stood Annfield Park containing Annfield House said to be haunted by a white lady and, on the west, villas with gardens where some married officers lived with their families when the infantry was in Gallowgate Barracks. The name Annfield was a compliment to Ann, the wife of James Tennant who about 1770 built Annfield House. Although the house was demolished in 1870, the name lives on in Annfield Place that fronts Duke Street. Recognised as the centre of the district, Bellgrove Street was crowded on holiday evenings such as Queen Victoria’s birthday.

ADELAIDE PLACE, Commercial Centre

Adelaide Place is named after the wife of William IV, the daughter of the Grand Duke of Saxe-Meiningen. Adelaide was born in 1818 and died in 1849, her husband having died in 1837, upon which Queen Victoria ascended the throne. William and Adelaide had no children, although William had ten illegitimate children by his mistress Dorothy Jordan.

Adelaide Place Baptist Church

At the corner of Adelaide Place and Bath Street is Adelaide Place Baptist Church, designed by Thomas Watson in 1877. Neo-classical in style with Italianate arches, it is the last remaining Baptist church in the city centre. Commercial conversion was completed in 1995 and the building serves as a guest house, nursery and auditorium as well as a church.

ADELPHI STREET, Gorbals

Adelphi Street fronts the River Clyde and was named from the Greek word adelphi meaning ‘brothers’, in honour of brothers George and Thomas Hutcheson. In 1601, these philanthropic brothers founded a hospital in Bridgegate. In the seventeenth century a hospital was not primarily a place for the sick, but an almshouse for homeless pensioners. Although initially the hospital provided shelter, most assistance was given by way of pensions or grants paid to ‘decaye’ merchants or widows and daughters in distress who were living elsewhere in the town. In 1659, the merchants rebuilt the now dilapidated hospital in the Bridgegate, the new building having a 164-foot-high steeple that remains to this day protruding through the centre of the former fish market. Hutchesons’ Hospital purchased a portion of the original Gorbals lands in 1790 and named their holding Hutchesontown, with Adelphi Street as the principal street.

ALBION STREET, Merchant City

Albion is one of the ancient Gaelic names for Scotland. Built on church lands, this street opened around 1808. From the earliest July Town Council minute existing (1574), it appears to have been the practice to hold a ritualistic open court of the burgh on ‘Fair even’, 6 July. This took place on a piece of rocky ground called Craignacht, somewhere in the region of today’s North Albion Street, the fair itself being held in the garden of the adjoining Greyfriars Monastery. In 1820, Greyfriars United Succession Church was built on the site of the old monastery from which it took its name. Demolished in 1972, a car park replaced it.

Along Albion Street’s west side, just north of Ingram Street, is the Daily Express Building of 1936, mainly of glass and black Vitrolite, later occupied by The Herald and Evening Times. It is now housing.

Anderston’s main street

ANDERSTON

Around 1725, John Anderson, decided to feu a village on an unprofitable section of his land, Stobcross Estate, near Gushet Farm (later Anderston Cross, demolished to make way for the approach to the Kingston Bridge). Feu is the Scots word for fee, which in turn comes from the old French feu. The granting of a feu gives the right to use land and property in return for an annual payment called a feu duty. Anderson named his village after himself and ‘Anderson’s Town’ later became known as Anderston.

At first, only a few mean thatched dwellings were built in Anderson’s Town, and it was not until John Orr of Barrowfield bought the estate in 1735 that the hamlet enlarged. Weavers took up the first feus and some street names derived from their processes – Carding Lane, Loom Place, Warp Lane, all sadly gone. Industries were established – Delftfield Potteries in 1751, Anderston Brewing Company in 1762 and Anderston’s main street the famous Verreville Glassworks with its distinctive cone-shaped chimney in 1776.

Anderson’s coat of arms

Anderston became a burgh on 24 June 1824. As its coat of arms, the burgh adopted the arms of the Andersons of Stobcross, with a few additions; a leopard with a spool in its mouth, a craftsman and a merchant symbolising trade and commerce and a ship in full sail representing foreign trade. The burgh’s motto was ‘The one flourishes by the help of the other’. Burgh status was not to last long – it was only 22 years before Glasgow annexed Anderston, in 1846.

ARGYLE STREET, City Centre

Nearly two miles long, Argyle Street is split into two contrasting parts. From Trongate to the magnificent Central Station viaduct it is bright and cheerful and one of Scotland’s busiest streets (Glaswegians describe any place packed to the gunnels as being ‘like Argyle Street on a Saturday’) and beyond that it is drab and uninspiring.

As late as 1750, what is now Argyle Street was entirely out of town, the city’s western boundary being the West Port Gate at the head of Stockwell. Immediately outside this was an unpaved rural road containing a few malt kilns or barns and a handful of one-storey thatched houses. Over the years, the road went by the names of St Enoch’s Gait, Dumbarton Road, and Westergait (the way to the west). The last of the old buildings, a thatched malt kiln at the corner of Argyle and Mitchell Streets, was demolished about 1830.

Thatched malt kiln at the corner of Argyle Street and Mitchell Street, drawn about 1820

Black Bull coaching inn

After the council took down the West Port Gate and Provosts Murdoch and Dunlop built twin mansions in 1750, the street rapidly filled, becoming Argyle Street around 1761 in honour of Archibald, third Duke of Argyll (spelling was flexible then). A short time later the Duke was dead and, when his funeral cortege passed through Glasgow on its way to the family burial grounds at Kilmun, his body lay in the city’s most fashionable hostelry, the Black Bull Inn, in the very street so recently named after him.A Marks & Spencer’s store occupies the site of the Black Bull that Robert Burns visited in 1787 and 1788, an association commemorated by a plaque on the store’s Virginia Street wall.

The first mention of Argyle Street in a business sense was in 1783 when R. Browne, Perfumer, advertised that he supplied ‘genuine violet powder for the hair of a neat, elegant and cheerful kind’. Around 1828, plumber George Douglas installed the city’s first plate glass windows in shops he owned on the north side of Argyle Street just east of Buchanan Street. It was considered generally ‘a great risk and monstrous extravagance’. In 1891 at No. 42, pool could be played every evening for 1s an hour at the Union Billiard Rooms, the largest in Scotland.

Across from Marks & Spencer is the site of Graftons’ Ladies Fashion Store, the scene of a tragic fire in 1949 when 13 women and girls died. Five employees saved themselves by climbing along the building’s top-storey ledge, crossing the roof of the adjoining Argyle Cinema and then dropping a considerable distance to the next building’s roof (the old Dunlop mansion) where firemen with ladders rescued them. Others jumped into Argyle Street where thousands of passers by gathered to watch the spectacle.

John Anderson’s Royal Polytechnic (the ‘Poly’ to all) took up the whole block between Dunlop Street and Maxwell Street. He introduced the department store to Scotland in the 1840s and claimed to have pioneered the idea of universal trading under one roof, his philosophy being ‘keen prices for a quick return’. In 1925, his son sold out to Lewis’s who gradually rebuilt the old Poly into the largest provincial department store in the country. The interior was modernised in 1988 and Debenhams now occupy the building.

Diagonally across from Debenhams to the west is Scotland’s oldest covered walkway, the Argyll Arcade (1828) built by John Robertson Reid who toured Europe studying arcades before deciding what kind to give to Glasgow. What he and architect John Baird came up with was an elegant, Parisian-style, hammer beamed, glass-roofed structure that connected Argyle Street with Buchanan Street. (The difference between the spelling of the Argyll Arcade and Argyle Street is that people spelled names any way they chose in the old days, and there are as many Argyles as Argylls on maps of the times. Today Argyll is accepted as correct.) From the beginning, children adored visiting the Arcade, loving the sheer magic of what appeared to them to be a ‘brightly lit cave’.

The Dunlop mansion in 1889, when it had come down in the world by being converted into shops

Just west of the arcade is Cranston House (the former Crown Tea Rooms), an eighteenth-century building gifted to Kate Cranston by her bridegroom in 1892. Miss Cranston remodelled the building with projecting eaves, gables, fancy dormers and a tower with a spire. The interior was by George Walton and the furnishings by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who turned the basement into a Dutch Kitchen with a fireplace as its focal point in 1907. A renovation some time ago uncovered the fireplace and decorative tiles, which were photographed for posterity.

Directly across the road from Cranston House is the neat twin-towered building that survived a demolition order in 1935. It opened in Edwardian days as Crouch’s Palace of Varieties, became the Wonderland Theatre, then the St Enoch Picture Theatre and is now occupied by shops.

The massive domed warehouse built in 1903 at the north-west corner of Argyle Street and Buchanan Street for Stewart & Macdonald Ltd. has two giant sculptured figures supporting the Argyle Street doorway. They were cheekily nicknamed Stewart and Macdonald after the proprietors.

Argyle Street in the 1920s

West of the Central Station viaduct to the motorway all that is of interest is the former Anderston Cross branch of the Glasgow Savings Bank (1899–1900) by architects James Salmon Jnr. and John Gaff Gillespie.

BAIN STREET/SQUARE, Calton

In the heart of Barrowland, this area was driven through the narrow closes of New Street (including the notorious Whisky Close) as part of the City Improvement Trust’s programme to get rid of the town’s worst slums. It was named after James Bain (Provost 1873–77) whose wealth of knowledge and business experience proved to be of great service to the Council.

Flanking an entrance to the Barrows in Bain Street is the former William White Clay Pipe Factory (1877) that, in its heyday, produced around 14,400 pipes per day in 700 different designs. The distinctive red and yellow brick façade was originally intended to be stone but costs determined otherwise. It has now been converted to housing.

BARRACK STREET, Gallowgate

Built on lands anciently known as the Butts where the burghers mustered at the Wappenschaw (weapon showing) to practice archery, hence the Butts. It was there in 1544 during the minority of Mary Queen of Scots that the bloody Battle of the Butts was fought between Regent Arran and the Earl of Lennox. Although 300 fell on either side, Arran won, and Glasgow, supporter of Lennox, was plundered with even windows and doors being carried off. Covenanting times saw another battle in the same place. Defeated at the Battle of Drumclog in 1769, Claverhouse retreated to Glasgow. Encouraged by their success the Covenanters entered the city and clashed with royalist soldiers who ambushed them in the Gallowgate. This time they lost, and Claverhouse gave orders not to bury his enemies’ dead bodies, but to leave them for the butchers’ dogs to eat.

A large portion of the land was gifted to the government in 1795 as a site for infantry barracks. Barrack Street opened the same year and formed the eastern boundary of the barracks that accommodated 1,000 men and cost £15,000. Previously soldiers were billeted on the inhabitants. The first regiment to occupy the quarters was the Argyllshire Fencibles, commanded by the Marquis of Lorne, later Duke of Argyll. When, a century later, new barracks were built in the north-west of the city the Council hoped the War Office would hand the ground it had enjoyed the free use of back to the city for use as a much-needed garden space. But no, it was sold for a very large sum to a railway company.

Barrack Street, 1885, drawn by David Small

There was a pighouse in Barrack Street, not a curing house for pork, but a pottery.‘Pig’ was a Scottish term used for domestic earthenware said to derive from the Gaelic pigadu, an earthenware jug. Nowadays ‘pig’ is confined to hot water bottles, but it used to refer to pottery chimney cans and people used to say after a storm that ‘a pig had fallen aff the lum’. The Water Authority dug up several of these wares in 1913 and deposited them with the People’s Palace.

BARRAS (BARROWLAND), Calton

Most people believe that the name ‘Barras’, Glasgow’s famous weekend street market, is a corruption of ‘the barrows’, but there are more likely explanations of the nickname. The old city Gallowgate Port was called ‘The Eyst Barrasyet’ that means gate in, or beside, a barrier. Alternatively, the ground occupied by the ‘Barras’ was part of the ancient Barrowfield lands, said to mean either ‘the Burrow or Burgh Field’.

Regardless of the name’s origin, there is no doubt as to how the market came about. Few hawkers owned their own barrows and, in the early 1920s, Maggie and James McIver were in the business of renting them out to stallholders around Gallowgate at 1s 6d per week from their yard in Marshalls Lane. (Incidentally, it was in this lane that the first purpose-built Catholic chapel in Glasgow was built.) When several tenements were demolished in the area, the McIvers bought the ground to use as a permanent market site. They built stalls and, by 1928, the market was roofed and enclosed. Maggie McIver became known as the ‘Barrows Queen’.

Barrowland Ballroom (photograph by Iain Taggart)

The famous Barrowland Ballroom opened on Christmas Eve 1934. It was said that Lord Haw-Haw earmarked the ballroom as a target for the German Air Force during World War II because of its popularity with the American Forces. Billy McGregor and his Barrowland Gaybirds was the resident band, but over the years many celebrity bandleaders appeared including Joe Loss, Henry Hall, Johnny Dankworth and Jack Hilton.

BATH STREET, Commercial Centre

Bath Street was named to commemorate the city’s first public baths. In 1802, William Harley, a wealthy merchant, bought large stretches of the Blythswood Estate lands at Sauchie Haugh where he built his house Willowbank. To tempt people to build on his land he established a beautiful pleasure garden with summerhouse, bowling green and 30-foot view tower, known as Harley’s Hill, or later Harley’s Folly, where Blythswood Square now is.

King’s Theatre, Bath Street

When that novelty wore off, Harley came up with another ambitious scheme. Supply water directly to the citizens’ doors, all water then being available only from public wells. Purchasing a long strip of land to the south of Sauchiehall Street, he built a roadway on the line of what is now Bath Street. From fine springs near his house, he led water to a reservoir on Garnethill and, using special horse-drawn four-wheeled carts ornamented on top with a gilt salmon, supplied the city with water at a ½d the stoup. Each King’s Birthday the carts, decorated with flowers, formed a procession. This was Glasgow’s first effort to provide a public water supply on a large scale.

Taking advantage of the fad for ‘taking the waters’, Harley opened on his new road (at the corner of Bath and Renfield Streets) swimming and other baths with dressing rooms, reading rooms and various conveniences. Harley’s road was nicknamed Bath Street, which it remained.

Alongside the baths, Harley built a byre for 24 cows to provide his customers with milk. Then it occurred to him that Glasgow was in need of a proper supply of pure sweet milk. The byre expanded to an immense dairy of over 200 cows, milk houses and pigsties. Everything was spotless and ‘Harley’s Byres’ became a tourist attraction; even royalty visited them.

Alas, the Napoleonic Wars and speculative building developments ruined William Harley and he died in 1829 en route to St Petersburg to build a dairy for the Empress of Russia that may have restored his fortunes. Only the name of Bath Street remains to commemorate the enterprises of a man who was a true pioneer of the city.

Bath Street has two churches – Adelaide Place Baptist (1875) and St Stephen’s Renfield (1849). There was another church, the Elgin Place Congregational (1855), which was converted into a nightclub before it burned down in 2005 and had to be demolished. At the bottom end of this still elegant street, many original Georgian buildings remain while, at the top end The Griffin Bar (originally Kings Arms, 1903), with Art Nouveau woodwork and glass, and Frank Matcham’s red sandstone King’s Theatre (1904) are of particular interest. Surmounting the entrance to the theatre is its mascot, a little stone lion holding a shield.

BELL STREET, Merchant City

Some believe that the first post-medieval street in the city (1710) was named after John Bell, a Lord Provost of Glasgow, but others are of the opinion it was after James Bell of Provosthaugh who, among others, sold land and properties to the Council in 1676 for the formation of a new street (Bell’s Wynd).

For this exercise, Provost Bell gets the honour. An ardent royalist, he was present at the battle of Bothwell Bridge between the Covenanters and the Government troops led by the Duke of Monmouth, an illegitimate son of King Charles II. After the fight, Bell rode to Glasgow and sent out all the bread he could find to the Royalist army, and to each troop and company he gifted a hogshead of wine taken from the cellars of those citizens who aided the rebels. John Bell’s reward came on 27 October 1679. By warrant from Whitehall, the king authorised the Lord Chancellor to confer on him a knighthood. Two years later, the Duke of York, later King James VII, stayed at Bell’s Saltmarket house when he visited Glasgow.

Ten years before the street opened there was a flesh market in the area, the main place to buy butcher meat in the city. The Herald, or as it was then, The Herald & Advertiser, was printed for 22 years at 6d a copy in Bell Street, (Glasgow Herald Close) also the home of the second Glasgow Police Office, one stair up. Bow’s Furniture store at the corner of Bell Street and High Street was the first shop to have an electric sign and, a year later, the first to receive the electricity that was supplied to Glasgow in 1890. The shop was converted into flats.

Bell Street, 1876, drawn by David Small

Nothing exists of the original street and nearly all the late Victorian warehouses, such as those built in 1881–83 for the Glasgow & South Western Railway, have been converted into housing.

BELL O’ THE BRAE, Townhead

In old Scots, the Bell o’ the Brae is a term applied to the highest part of the slope of a hill, ‘bel’ signifying a prominence.

The name is rarely used in Glasgow today, but in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it was the most important spot in Glasgow at the intersection of High Street with the Drygate and Rottenrow where the Market Cross stood. Dangerously steep in early times, the ascent was lowered in 1783 to make the Cathedral more accessible to churchgoers. Over the years, more was sliced off the top causing the removal of many picturesque wooden houses that fronted the street.

Bell o’ the Brae, seventeenth-century thatched cottages

Glasgow’s first battle took place at the Bell o’ the Brae. Around 1300 there was an English garrison in the Bishop’s Castle at the top of High Street. Sir William Wallace attacked the Castle and the English chased him down High Street, but just there, as planned, the Scots turned to fight. Another Scottish force, led by Wallace’s uncle, Auchinleck, came up the Drygate and attacked from the rear. The English, hemmed in back and front, were defeated. Some cast doubt on the authenticity of this tale, but all histories of Glasgow include it.

Today Burnet & Boston’s competition-winning, red sandstone, crow-stepped tenements sweep majestically round into Duke Street and George Street (1901). The buildings are Arts and Crafts versions of seventeenth-century tenements and replaced the old thatched, wooden houses and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century tenements that once lined the street.

BERKELEY STREET, West End

Berkeley Street can be regarded as a continuation of Bath Street across the motorway. It was named after Thomas Moreton Fitz-Harding, sixth Earl of Berkeley (1796–1882). For a time the family owned Berkeley Square in London. At the corner of Berkeley and Claremont Streets stands the former Trinity Congregational Church converted for use by the Scottish National Orchestra Society in 1978 and now known as Henry Wood Hall.

The infamous Dr Edward Pritchard who poisoned his wife and mother-in-law once lived at No. 11 Berkeley Terrace. He was known as the ‘Human Crocodile’ as he had his wife’s coffin lid opened so that he could kiss his victim on the lips. In 1865, 30,000 people watched him hang in front of the prison at Saltmarket. It was the last public hanging in Glasgow.

No. 11 Berkeley Terrace

BENNY LYNCH COURT, Gorbals

Benny Lynch Court, designed for the New Gorbals Housing Association, was named in honour of one of the Gorbals’ most famous sons, Benny Lynch (1913–46), regarded by many as Scotland’s greatest boxer.

Benny’s story was from rags to riches and back to rags. Of slim build, only 5 feet 3 inches in height, and at the tender age of 21, he was the first Scot to win a world title – the flyweight championship of 1934, beating Jackie Brown, who had held the title for three years. He defended and retained his British and World titles against Pat Palmer in 1936. In 1937, he fought American Small Montana in London and after a 15-round fight was pronounced the winner. The fight is still regarded as the finest-ever flyweight match. His most celebrated local fight was in 1937 when he beat Peter Kane at Shawfield Park by scoring a knockout in the thirteenth round. That was the last time that Benny was able to meet the 8-stone maximum for the flyweight class and he took solace in drinking and finished-up fighting in the boxing booths of his youth. Continuing to treat whisky as food, a penniless and ill Benny Lynch was taken to the Southern General Hospital on