Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Origin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

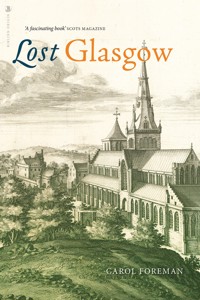

In this informative and beautifully illustrated book, Carol Foreman traces Glasgow's history through buildings which have been demolished, but which once played a central part in the life of the city. Beginning with the medieval age, she goes on to look at a massive selection of buildings right through to the 1930s. The result is a fascinating picture of how the city evolved and how major events over the centuries affected its trade, people and environment. Churches, banks, hospitals, theatres, cinemas as well as domestic buildings all feature in this illuminating journey through Glasgow's rich architectural past.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 269

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

LOST GLASGOW

To Iain Paterson with thanks for his help and patience in answering my many queries

This eBook edition published in 2013 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2002 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © Carol Foreman, 2002

The moral right of Carol Foreman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-634-2 Print ISBN: 978-1-84158-278-8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

CONTENTS

Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Medieval Town, 1175–1560

CHAPTER 2

The Reformation to the Act of Union, 1560–1707

CHAPTER 3

From Merchant City to Victorian City, 1707–1837

CHAPTER 4

The Victorian City, 1837–1901

Appendix

GLASGOW1

Glasgow to Thee thy Neighbouring Towns give place,

’Bove them thou lifts thine head with comely grace.

Scarce in the spacious Earth can any see

A City that’s more beautiful than thee.

Towards the setting Sun thou’rt built, and finds

The temperate breathings of the Western Winds.

More pure than Amber is the River Clyde,

Whose Gentle streams do by thy Borders glyde;

And here a thousand Sail receive commands

To traffick for thee unto Forraign Lands.

The buildings high and glorious are; yet be

More fair within than they are outwardly.

Thy Houses by thy Temples are outdone,

Thy glittering Temples of the fairest Stone:

And yet the Stones of them however fair

The Workmanship exceeds which is more rare.

That Neptune and Apollo did (it’s said)

Troy’s fam’d Walls rear and their foundations laid.

But thee, O Glasgow! we may justly deem

That all the Gods who have been in esteem,

Which in the Earth and Air and Ocean are,

Have joyn’d to build with a Propitious Star.

INTRODUCTION

While Lost Glasgow deals principally with Glasgow’s lost architectural heritage from medieval times to the end of the Victorian age, interwoven is the story of how the city evolved and how major events throughout the centuries affected its people, trade and environment. The area covered by Lost Glasgow is roughly that contained within the inner ring road (the M8 north of the Clyde), and buildings are grouped as to when they were built, not when they were demolished, allowing the history of the city to unfold. This would not have been possible if the buildings had been arranged in the order in which they were demolished, as most of ‘Old Glasgow’ vanished in Victorian times and most of the Victorian buildings that have been lost were destroyed in the second half of the twentieth century.

As Glasgow has lost so much of its architectural heritage, it has been very difficult to decide which buildings to include in Lost Glasgow. Consequently, there are probably many important buildings known to readers that have been omitted. For this, I apologise.

For the loss of so many of its historic buildings, Glasgow has only itself to blame. It has never been sentimental about its old buildings. It has been a point of civic pride to destroy and build better, and if old buildings got in the way of any new plan, they were swept away, supposedly in the name of progress. All that is left of the medieval city are the Cathedral and Provand’s Lordship (1471), just one of the thirty-two prebendal manses that existed around the Cathedral. The only other relics of ancient Glasgow are three seventeenth-century steeples, the Tolbooth (1626), at the foot of High Street, the Tron (1636), in Trongate, and the Merchants (1665) in Bridgegate.

Although the Georgians expanded the city outside its medieval boundaries, they unforgivably allowed the Bishop’s Castle to become a ruin and let the Cathedral fall into disrepair. They also destroyed the fifteenth-century St Nicholas Hospital and the seventeenth-century Tolbooth, Hutchesons’ Hospital and Merchants House. The historic Shawfield Mansion, one of the earliest examples of a Palladian villa in Britain, disappeared in 1795 to make way for Glassford Street.

The disintegration of ‘Old Glasgow’ began in Victorian times with the pioneering City Improvement Act of 1866, which set up an Improvement Trust to clear and redevelop 90 acres in the notorious slum localities around Trongate, Saltmarket, Gallowgate and High Street. Included were parts of Calton and the Gorbals. The designated area had a population of over 50,000. The railway companies also did their bit, as their viaducts and bridges swept through the heart of the historic city, tearing down seventeenth-century houses in the Bridgegate. The Union Railway Scheme alone demolished over thirteen hundred houses when it ran its lines through Gallowgate, Saltmarket, Bridgegate and Glasgow Cross, with the Improvement Trustees paying for the widening of spans to allow for more spacious street layouts.

The Trustees of the Glasgow Improvement Scheme had the wisdom to commission Thomas Annan to make a photographic record of the old streets, wynds, vennels and closes before they were cleared. Three editions of The Old Closes and Streets of Glasgow were published between 1868 and 1900; the last edition included photographs taken after Annan’s death in 1887. As the work of the Trust continued into the twentieth century, each edition had a different set of photographs.

Before the age of photography, illustrations by people like Joseph Swan, Andrew Donaldson, Thomas Fairbairn, William Simpson and David Small gave a wide-ranging idea of the city in the nineteenth century. Many of these illustrations appear in Lost Glasgow, as do maps showing the layout of the city through the ages.

As a matter of interest, no pictures of Glasgow exist before the end of the seventeenth century. Captain John Abraham Slezer, a Dutch soldier who came to Scotland in the 1660s and 1670s to help with military arrangements during the Covenanting troubles, was responsible for the first. While he moved about Scotland, he sketched many of the ‘interesting prospects’ he saw, but, as his sketches were not good enough for publication, after a visit to his native land he brought back a skilled ‘prospect’ painter, who drew 57 large views that were published in a volume called Theatrum Scotiae in London in 1693. Three of the scenes were of Glasgow – a view from the Merchants’ Hill (the site of the Necropolis), a view of the south riverfront, apparently from Govanhill, and a view of the College and Blackfriars Church.

Although portrayed as ruthless vandals who destroyed almost all of Glasgow’s old town and its Georgian buildings, in essence the Victorians were trying to improve the city, as by the middle of the nineteenth century the old town had become a vice-ridden overcrowded slum where cholera and typhus raged. Where they went wrong was that instead of just knocking down the slum dwellings, in their reforming zeal they destroyed many fine old houses around Glasgow Cross, the last of the half-timbered houses and the medieval houses around the Cathedral. While that was bad enough, under the guise of improving the Cathedral they mutilated it by demolishing its two medieval western towers. They also demolished buildings designed by the famous Adam brothers. Most inexcusable, however, was the greatest loss of all, the Old College in High Street, recognised as the finest group of seventeenth-century buildings in Scotland, which the University and the Council sacrificed to a railway company that demolished them.

Should we commend or condemn the Victorians for their redevelopment of the city? Possibly a bit of both as they did make the town a more pleasant and much healthier place to live, and if by removing the slums, which were the worst in the country, the picturesque was sacrificed, the means justified the end. Moreover, if they had not replaced the simple early eighteenth-century buildings extending west of Buchanan Street up to Blythswood Hill with exceptional office buildings designed by architects of outstanding merit, the city would not today be able to claim its title of ‘the foremost Victorian city in the world’.

If the Victorians, whose buildings were, on the whole, worthy successors of the old, were not the worst vandals of Glasgow’s historic buildings, who were? Our twentieth-century forebears, especially those of the 1960s and 70s, who blithely knocked down magnificent Victorian buildings and replaced them with concrete monstrosities that might have been economic and functional but added nothing to the street scene or the visual attractiveness of the city. In addition, the motorways, which began in the late 1960s to alleviate traffic congestion in the city, did more damage to it than had the Victorian railways.

The twentieth century had barely begun when Kelvingrove House, designed by Robert Adam, was demolished to make way for a section of the 1901 Exhibition. Eleven years later, the Adam brothers’ Royal Infirmary was also demolished. There had been a public outcry, but public opinion rarely carried much weight in Glasgow when its leading citizens had made up their minds to do something. Actually, like its councils throughout the centuries, few Glaswegians bothered about buildings of historical or architectural merit. With a few exceptions, like the removal of the Cathedral towers, the Old College and some Adams’ buildings, they were generally in favour of redevelopment.

Glasgow, unlike many other great industrial centres, suffered comparatively little damage from enemy action in the two World Wars. In the 1914–18 war bombs were dropped on Edinburgh but none on Glasgow. During the 1939–45 war Glasgow was bombed several times, and although George Square narrowly escaped destruction in a night raid in September 1940, it was in the last raid on Glasgow in March 1943 that the only real architectural loss was suffered – an Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson church in Queen’s Park. (The heavy and prolonged night raids in the spring of 1941 were mainly concentrated on Clydebank and Greenock.)

Despite requiring no post-war reconstruction, after the Second World War the city planners were determined to turn Glasgow into ‘the most modern city in Europe’. They saw no merit in Victorian buildings, and if the plan put forward by Robert Bruce, the City Engineer, had been carried out, few if any of the city centre’s historic buildings would still be around today. Because the city was emphatically against a loss of population, Bruce opposed the Clyde Valley Plan of 1946 proposing that new towns should be built to relieve Glasgow’s housing problems. He wanted to demolish most of the city centre, including the City Chambers, and put up high-rise flats to house the population. Fortunately, Bruce’s plan was not executed, and in the 1950s peripheral housing areas were created – Drumchapel, Easterhouse, Pollok and Castlemilk. His ring road plan, however, revised in the Glasgow Central Area Report and Highways Plan of 1965, had the greatest impact on the city centre by cutting it off from its immediate surroundings. Later, the east part of the ring road was altered so that St Andrew’s Church and its environs were still within the city centre. The inner ring road cut through Anderston Cross, Charing Cross and St George’s Cross, and obliterated Cowcaddens. Sharing the blame with Glasgow for the destruction was the Secretary of State for Scotland who approved it.

In 1964, when the Royal Institute of British Architects held its annual conference in Glasgow, architects from all over Britain, most of whom had never been in the city before and who were under the impression that it was a slum ready for demolition, were so astonished by the city’s architecture that they said it had to be conserved at all costs. Chairman of the RIBA’s planning committee, Lord Esher, could not believe what he saw and said it was a great city built of stone, far better than we could build today. ‘We must preserve it,’ he said.

To preserve it, however, was not the aim of the city fathers, and Frank Wordsall, in his book The City That Disappeared, makes mention of what happened when the newly formed conservationists The Victorian Group asked the Lord Provost to join an organised walk around the city centre to draw attention to the wealth of buildings there. The idea did not appeal to the Lord Provost, who asked, ‘Do they seriously suggest that the local authority should have to carry the financial burden of preserving all the city’s Victorian buildings? I would not like the impression to get out that Glasgow was a Victorian city! Many old buildings will have to come down, and considering the state of them, whether Victorian or Edwardian, thank goodness for that.’ With an attitude like that from its first citizen, is it any wonder so much of Glasgow’s heritage vanished? Was it lack of education in matters architectural, no interest in the city’s past, or just that it was believed that new was better? Whichever it was, Glasgow was in danger of losing buildings of architectural excellence unequalled in Britain.

A list of buildings of architectural or historic interest had been drawn up in the 1950s. However, as the greatest emphasis was on buildings dating from before 1700 and less significance was attached to a building the more recent it was, Glasgow was at a disadvantage – its buildings of interest were predominantly nineteenth and early twentieth century. Even the 1969 Act, which laid down that as an added precaution local authority consent had to be obtained before a listed building could be demolished, did not help Glasgow, as it was the local authority here that was doing the demolishing, often using the excuse that a particular building was dangerous and had to come down immediately. Other owners of old buildings were just as unscrupulous as the local authority, many deliberately allowing their properties to deteriorate in the hope that they would be allowed to demolish them.

In 1971 Glasgow appeared to have dropped its notorious hostility towards preservation and conservation, as it asked Lord Esher to make a general appraisal of the problems of building conservation in the city and to recommend what steps should be taken to set up and develop an effective policy for protecting and enhancing the city’s good buildings and townscape. Among Lord Esher’s many recommendations was the setting up of conservation areas such as Central, Kelvinside, Hillhead, Dowanhill, Pollokshields, Strathbungo and Dennistoun. (Today Glasgow has twenty conservation areas, ranging in character from the city centre and Victorian residential suburbs to the rural village of Carmunnock. These areas cover 1,423 hectares of the city and provide homes for 10 per cent of the population. The Central Conservation Area influences the commercial sector, both as a desirable working environment and as a visitor attraction.)

Lord Esher pointed out that conservation would cost money – from occupiers, the Corporation and central government – and would need consistent imaginative planning, but it would be worth it. ‘A great many Victorian houses in their old settings and Victorian monuments in the city centre are built with more craftsmanship than we can hope to emulate or than the world is ever likely to see again.’

As the 1970s was the worst decade in the twentieth century for the demolition of irreplaceable architectural and historic buildings in Glasgow, the Corporation obviously took little notice of Lord Esher’s recommendations. The exercise must just have been a ploy to keep conservationists quiet, as in 1972 the convener of the Highways Committee announced that he did not want the ‘new Glasgow to be a museum piece for the delectation and delight of visiting professors of architecture’. (There was no danger of that as the over-ambitious plans of the Highways Committee were responsible for unparalleled destruction throughout the city.)

By the early 1980s the local authority’s attitude to rehabilitation and conservation had begun to change, and many of the city centre’s Victorian buildings were renovated and stone-cleaned. Demolition was not quite as extensive and sometimes buildings were retained although their interiors were gutted. Other times only the facades were retained and incorporated into new buildings.

Although nowadays the aim of Glasgow City Council is to protect, enhance and promote the city’s rich and varied architectural heritage, if buildings of architectural or historic interest are to be retained, they need to be economically viable and functional. Owners are not interested in keeping them purely for their visual appeal, or for ‘prestige’ value, as the cost of maintaining them is incredibly high. Where maintenance has been ignored or where buildings have been vacated and become the target for vandalism, the Council can take statutory action against the owners to secure, repair or upgrade these buildings and return them to a productive use that may be different from their original purpose.

While it is clearly beneficial to find new uses for uneconomic obsolete buildings of architectural or historic interest, because of legislative controls restricting adaptation it is not always easy. Moreover, sometimes buildings have been so neglected that there is no option but to demolish them as they are either unsafe or reinstatement would be ruinously expensive. When that is the case, however, care should be taken to make sure redevelopment harmonises with existing buildings. Good-quality modern design can bring old and new together to create an attractive evolving urban landscape, and while Glasgow has various new buildings of which it can be proud, too many (particularly those of the 1960s and 70s) are shoddily built and of no architectural merit. Even if Glasgow had wanted to rebuild according to original designs, as did Germany, it could not have done so because, after the Second World War, officials destroyed many of the old architectural drawings.

Some old buildings are made economically viable and functional by the addition of extra floors of modern design, which, despite being set back behind the cornice and parapet level to make them as unobtrusive as possible, often do not sit comfortably with the original architecture.

Scottish government ministers are responsible for identifying buildings of special architectural or historic interest throughout Scotland. Glasgow has around 1,800 buildings listed as being of special interest. They are graded A, B and C(S) according to their merits. Category A covers buildings of national and international importance, such as Glasgow School of Art, and accounts for 15.45 per cent of all listed buildings in Glasgow. Category B (69.65 per cent) takes in those of regional or local significance, and Category C(S) (14.90 per cent) contains buildings of more modest architectural or historic interest. The interiors and exteriors of category A, B and C (S) buildings are statutorily protected and are covered by a range of listed buildings controls – they may not be demolished or altered without prior listed-building consent from the local planning authority. (By the time of publication of Lost Glasgow, the number and categories of listed items in the city may have changed. Some buildings may have been demolished and others might have been reclassified as styles, attitudes and values change. Areas and buildings once seen as ordinary can, over time, be perceived in a different light, perhaps as well-preserved examples of a particular style. Historical evidence can also change the assessment of items.)

In conclusion, after many years of misguided planners undervaluing and destroying Glasgow’s architectural heritage, today its planning authority, in tandem with heritage societies like Historic Scotland and the Scottish Civic Trust, does all in its power to ensure that the city remains the ‘foremost Victorian city in the world’.

CAROL FOREMAN, 2002

CHAPTER 1

MEDIEVAL TOWN, 1175–1560

Nothing is known of Glasgow’s history for five centuries after the death in AD 603 of St Mungo, Glasgow’s patron saint, who established a church and a community on the banks of the Molendinar Burn around AD 543. We can only begin to chart the development of the city from 1116, when King David I, then Prince of Cumbria, restored the see of Glasgow according to the canons of the Church of Rome and appointed his tutor, John Achaius, to the bishopric.

At David’s command, one of Bishop Achaius’ first duties was to detail all the lands and possessions that had once belonged to the church of St Mungo. This famous document, called ‘The Inquest of David’, listed the territorial possessions throughout the diocese, information that is invaluable as there is a dearth of records from that early period. Among the lands restored to the church were Ruglan (Rutherglen), Perdeyc (Partick) and Guven (Govan), all names that have survived until today. New lands were bestowed on the see when David became king. Under Achaius, the diocese was divided into two archdeaconries, Glasgow and Teviotdale, and various offices and prebends were established. A prebend is a share in the revenues of a cathedral or church allowed to a clergyman who officiates at stated times.

In 1124 Bishop Achaius began building a cathedral on the site of St Mungo’s church, and after its consecration on 7 July 1136 the little cathedral town by the Molendinar began to play a part in the affairs of the kingdom.

Achaius was not only Bishop of Glasgow. He was Chancellor of Scotland and from the first had to fight the English claim that his bishopric owed obedience to the Archbishop of York. The fight was still going on in 1175 when Jocelin, Abbot of Melrose, was chosen to be fourth Bishop of Glasgow. No sooner was Jocelin elected, however, than he went to Rome and secured a papal order that the Scottish bishops should yield obedience to Rome alone. The diocese of Glasgow covered a large geographical area, with over 200 parishes from Luss in the north to Gretna in the south, and because of its importance was recognised by the Pope as a ‘special daughter’ of the Holy See. The see was raised to an archbishopric in 1492 with jurisdiction over the bishoprics of Dunkeld, Dunblane, Galloway and Argyll.

George Henry’s mural in the Banqueting Hall in the City Chambers representing King William the Lion granting the charter for the institution of Glasgow Fair.

As a reward for Jocelin’s success in Rome, King William the Lion granted Glasgow a charter in 1175 making it a burgh of barony with the right to hold a weekly market on Thursdays. Being a burgh of barony meant that the city, and the church lands round it, belonged to the Bishop. He was the overlord of the whole area and, like any baron, had powers of life and death over his serfs and the right to collect taxes from the freemen living in the burgh. He also appointed the provost, bailies and sergeants of the town. In 1450, Glasgow became a burgh of regality, the Bishop representing the king’s authority rather than, as before, ruling in his own right. It was not until 1611 that Glasgow became a royal burgh directly answerable only to Parliament and the king. In 1690, William and Mary granted the city ‘the power and privilege to choose its own magistrates, provost, bailies and other officers’.

The presence of the Bishop, the clergymen connected with the Cathedral and their many servants, together with the additional wealth brought into the town from the revenues of the extensive diocese, resulted in the king granting the city the right in 1190 to hold a yearly fair. A fair was a valuable privilege, as without it the trade coveted by the Bishops could not have been attracted to their burghs. The fair was to be held for a week commencing 7 July. A charter of 1211 confirmed the fair, ordering the King’s Peace to be kept during this time under a fine of 180 cows for manslaughter.

The fair established commerce in Glasgow, including trade with foreign countries, particularly France, with whom Glasgow had dealings from a very early period. A charter of 1363 says that among the articles on sale at the Glasgow Fair were French gloves and that Mary, Countess of Menteith, granted her kinsman Archibald, the son of Colin Campbell of Lochow, the lands of Kilmun on Cowal, the reddendo (service to be rendered) being the yearly payment of a pair of Paris gloves at Glasgow Fair.

As Bishop Achaius’ cathedral had been destroyed by fire in 1192, Bishop Jocelin began rebuilding it, and in 1197 enough was ready for a rededication. Jocelin also built a tomb to St Mungo. Jocelin died on 17 March 1199 and was buried on the right-hand side of the Cathedral’s choir. If it had not been for Jocelin’s biography of St Mungo, Glasgow would have known nothing of its patron saint. It is also to Jocelin that Glasgow owes its burghal constitution, the institution of its markets and fair, and the foundation of its great church, which subsequent Bishops added to almost until the Reformation.

CATHEDRAL TOWERS

Additions to the Cathedral included the Consistory House and the Tower at the western end. The Consistory House, at the southwest, had probably been intended for a tower but instead of being carried up was finished with gables. In the ancient records, it is called the library house of the Cathedral and for 200 years the ecclesiastical courts were held in it. It was a picturesque building supported by buttresses and was lit on the south side by various windows, square-headed and pointed. The taller, square northwest Tower was 126 feet high, and on each side near the top were two windows with rounded arches. In the upper part of the Tower were grotesque sculptures. During its lifetime the Tower served as a prison, a court, a chapel and a burial place. Although it is not known exactly when the Consistory House and Tower were built, the mid-thirteenth century is thought to be correct.

Apart from their antiquity, both buildings were valuable in adding to the beauty of the Cathedral, and the Tower, although not in keeping with other parts of the building, was essential to the proper balance of the structure. Yet, incredibly, in the 1840s the Consistory House and the Tower, both in a perfect state of preservation, were pulled down. At the time, the Glasgow Herald noted that a man was seen stirring the burning rubbish – the priceless post-Reformation records of the Cathedral.

One excuse for the vandalism was that two finer towers, which would improve the Cathedral, would replace the Consistory House and the Tower. Other excuses were that the Tower was an eyesore out of keeping with the Cathedral’s magnificence and that the Consistory House and the Tower were later in date than the nave and therefore not part of the original church design. When the Tower was demolished, however, it was found that the aisle window against which it had been built had never been glazed, proving that the Tower was added after the nave had been started but before it was finished. If the Tower did not form part of the original design of the Cathedral, therefore, its erection must have been decided on before the nave was completed. The Victorian architect John Honeyman believed the Tower to be coeval with the nave and fellow architect R. W. Billings thought the west doorway of the nave and the lower stage of the Tower were the oldest portions of the Cathedral.

View of Glasgow Cathedral with the Consistory House and Tower intact.

While Glasgow’s Victorian city fathers considered the Consistory House and Tower to be unimportant architecturally, old council minutes prove that their predecessors had regarded them as part of the ancient structure, thus equally deserving preservation with the other parts of the Cathedral.

When it was decided to demolish the Consistory House and Tower there was a public outcry, but despite important people, many of them architects, remonstrating with the council the Consistory House was demolished in 1846 and the Tower in 1848. When the Tower was removed, a large tombstone was found in the centre of the floor of the chapel with an armorial bearing on a corner, thought to have been the arms of the fourteenth-century Cardinal Walter Wardlaw. Before anyone could be found to properly decipher the arms, however, the stone was broken up and built into the north buttress of the west side of the Cathedral. The removal of the Tower was described as an act of barbarism.

Drawing of the west elevation of Glasgow Cathedral showing the Consistory House and Tower.

Although Glasgow has never been kind to its old buildings, the removal of the Consistory House and the Tower was the worst desecration of a building in the city and the mutilated Cathedral remains to this day a monument to ignorance.

This is the only picture extant of a Glasgow pre-Reformation church other than the Cathedral. It is from Captain John Abraham Slezer’s Theatrum Scotiae, published in London in 1693. The volume contained fifty-seven large ‘prospects’ of Scotland, three being of Glasgow – the Merchants’ Hill (the Necropolis), the south river-front, and a bird’s-eye view of the College and Blackfriars Church. The view was taken shortly before lightning destroyed the church.

BLACKFRIARS CHURCH

The Cathedral was not the only church in medieval Glasgow. There was also the church of the Black Friars. On the east side of the thoroughfare that became High Street Pope Gregory had founded a monastery in 1240 for the Dominicans, or Black Friars, whose church was built before 1246 – possibly in the preceding century. When King Edward I of England was in Glasgow in 1301, he lodged with the Black Friars, their establishment being the only place in the town capable of receiving the royal retinue. Like other Dominican buildings, it would have been highly furnished. The church, which had a steeple similar to that of the Cathedral, was described by Glasgow’s first historian, M’ure, as ‘the ancientest building of Gothic kind of work that could be seen in the whole kingdom’.

After the Reformation, the Crown bestowed Blackfriars Church upon Glasgow University, at that time still in the same part of town. In 1670 lightning struck the church, splitting the steeple from top to bottom and setting it on fire. The church was never restored and lay in ruins for years until a new church of a very different style was erected in its place in 1701. This was the Old College Church, which was demolished in the 1880s when the University moved to Gilmorehill.

Front view of Old College Church, 1848.

BISHOP’S CASTLE

Next in importance to Glasgow Cathedral was the Bishop’s Castle (roughly where the Royal Infirmary now stands), the residence and administrative headquarters of the Bishop, who had secular and spiritual responsibility for the burgh.

There are no records to show when the Castle of Glasgow, for such it was, was built. The first mention of it is in 1258 in the Chartulary of Glasgow (Chartulary – the city register), which refers to Bishop William de Bondington and states: ‘His palace is without the Castle of Glasgow’. The name Castle appears again in 1268 and 1290 when it is said to have a garden.

Painting by Thomas Hearne, c. 1782, of the Bishop’s Castle with Bishop Cameron’s Tower in the foreground. In the background is Glasgow Cathedral. The single-storey building across from the Tower was known as Darnley’s Cottage as it was built on the site of the Erskine Manse where Lord Darnley was alleged to have lodged in January 1567 when he was sick with smallpox and where his wife, Mary Queen of Scots, visited him.

Although the appearance and extent of the original Castle are uncertain, it is known that around 1438 Bishop Cameron added a great tower and that about 1510 Archbishop Beaton fortified it with a 15-foot-high wall with a bastion, ditch and tower. Archbishop Dunbar built the last addition around 1530, a towered gatehouse.

The Castle was both palace and stronghold, and in 1300 an English garrison held it until Wallace’s victory of the Bell o’ the Brae (the steep part of High Street that led to the Cathedral). When John Mure of Caldwell and others stormed and plundered the Castle in 1515, Archbishop Beaton began an action against Mure for ‘Wrangwis spoliation’ and detailed the goods stolen. Mure had to make restitution. It was after this raid that Archbishop Beaton built the 15-foot high wall.