Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

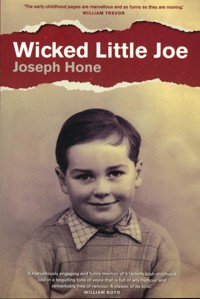

Ben Contini, a disenchanted painter of considerable talent, has just buried his mother. Rifling through the attic of her Kilkenny house he stumbles across a Modigliani nude, worth millions. Determined to learn the provenance of the painting, he and Elsa, a disturbed and secretive woman who accosts him at the funeral, become embroiled in the sinister world of Nazi art theft. But they are not the only one with an interest in the painting… Together they set off on a frantic journey that leads them from Dublin to France via the Cotswolds, down the Canal du Midi into Italy. The intrigue surrounding the shadowy half-truths about their exotic families becomes increasingly sinister as Ben and Elsa are forced to confront their pasts and their buried demons. Set in the 1980s, this is a fantastic new book from established thriller writer Joseph Hone, who weaves a breathless, galloping intrigue packed with narrative twists and sumptuous evocations of Europe's forgotten past.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 419

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GOODBYE AGAIN

Joseph Hone

The Lilliput Press

For Susie

Engaging in denial and repression in order to save oneself the difficult task of integrating an experience into one’s personality is of course by no means restricted to survivors. On the contrary, it is the most common reaction to the holocaust – to remember it as a historical fact, but to deny or repress its psychological impact, which would require a restructuring of one’s personality and a different world view from that which one has heretofore embraced.

—Bruno Bettelheim, Surviving the Holocaust, 1986

Contents

Title PageDedicationEpigraphONETWOTHREEFOURFIVESIXSEVENEIGHTNINETENELEVENTWELVETHIRTEENFOURTEENFIFTEENSIXTEENSEVENTEENEIGHTEENNINETEENTWENTYALSO BY JOSEPH HONECopyright

ONE

Ben’s Story

I saw the woman coming towards me at the reception in the big house at Killiney after my mother’s funeral.

My heart missed a beat. It was Katie.

But it couldn’t be her. Katie was dead. Yet how like her this woman was. The same measured, careful step, light on her feet, narrow shoulders. Same untended, short dark hair, flat-soled shoes, a casually unfashionable air. An impression of reserve: composed, decorous. Like Katie.

I was talking with the rabbi. My mother Sarah had been one of his congregation at the Adelaide Road Synagogue in Dublin. Now the woman hovered nearby.

I glanced at her again, uncertain. Perhaps it was the wine, promoting so strong a memory of Katie that I saw her now in any dark-haired woman, roughly the same looks, height and build. But no, this woman was so much like Katie – the same smallish height and build, the brown-green eyes, and the sharp cut of cheekbones, jawline, chin. Same compact body, where the shapes tended to be flat rather than curved, apart from the breasts, vaguely defined beneath a loose-fitting, navy-blue, silk blouse.

And more than the sum of all the parts – the same elusive ambiguous air: provocative yet guarded. A look that beckoned, but warned. ‘My body perhaps, but you will never possess me.’ It was as if Katie had been resurrected in a slightly altered physical state, but with a change of spirit and character, transformed into an easier, more available, less contrary person. A new Katie, who would wipe out the despair I felt in my loss of Katie herself – this new Katie, a wonderful gift, ready packaged, waiting for me a few yards away, a recompense.

My talk with the rabbi was interrupted by Sam McCartney offering condolences. McCartney was my mother’s solicitor and now sole executor of her estate. Ageing, in his seventies, but still a big, pushy, florid-faced man, an old rugby hearty who had once played prop forward for Ireland. He usually sported a houndstooth tweed jacket, sometimes a scarlet waistcoat. Loudly dressed, loud-mouthed. Now he was more soberly garbed. A man I’d never liked. Over-friendly, tricky. And partly to blame for some of the problems in my early life, through his influence over my mother – agreement about my ‘cheek’ as he’d put it to her, in my declining sensible jobs in Dublin after I’d left school and wanted to be a painter.

So I had no qualms in cutting him and moving towards the woman. Close to her now, the resemblance was more pronounced. This woman and Katie were almost twins. Seeing my surprise, and thinking it due to her having broken up my talk with Sam McCartney, she was apologetic.

‘I am sorry to interrupt. Forgive me.’

‘No, not at all. I’d had my say there.’ I couldn’t take my eyes off her, so that I had to apologize in turn. ‘Sorry … for staring.’

She made no acknowledgment of this. She seemed to have something more urgent in mind. ‘I don’t know quite where to begin,’ she said quickly.

She must have been in her mid forties. Katie had been the same age. Had been? It was hard to think of her in the past tense. And I’d tried not to think of her this way for nearly a week.

‘I’m sorry, Signor Contini,’ the woman went on, ‘I wanted to offer my sympathy on your mother’s death, but didn’t want to intrude at the service or cemetery.’

‘No, no, that’s quite all right.’ With several drinks on board already I found my stride with her in a bright manner. ‘Call me Ben. Certainly not “Signor”, I’m only half-Italian and barely know the country. And of course I don’t mind you coming here. My mother did have some friends of her own in Dublin. Though not many of this lot.’ I waved my bandaged hand – I’d burnt it the week before – at the room. ‘Half these dreadful businessmen and their pampered wives I don’t know at all. And most of the other half I’d prefer not to know. Very few of them knew my mother anyway. She was something of a recluse. But you knew her, obviously.’ I smiled. ‘You were a friend of hers.’

‘Well, no, actually. That’s the problem.’

She frowned, at a loss, and I saw a sudden look of fear in her face, as if she was about to be confronted by some danger in the big drawing room. This was unlikely, filled as it was by some sixty respectable, boring and now discreetly convivial mourners, including a government minister, crowding out the dark-panelled, heavily carpeted space with its two great mock-Gothic mullioned windows looking out over Killiney Bay. It was a premonitory alarm, I decided. The rough outlines for a full portrait that would one day tell the whole sad story. I gazed at her now, as if appraising her for that very portrait.

‘The problem?’ I asked.

‘Yes. You see, I didn’t know your mother at all. Or your father. Never knew anything about your family until my father spoke to me about you this morning.’

‘Your father?’

‘Yes,’ she rushed on, a memory of Middle Europe in her voice, firmer tones of America. ‘He’s very ill at home.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘He’s over eighty, and wanders. But he was quite clear this morning when he spoke to me about you and your family. He’d heard about your mother’s death somehow, and he said to me, “You must go to Sarah Contini’s funeral today, wife of old Luchino Contini. And speak to her son Ben. He’ll be there. He’ll explain everything. You must go and talk to him.” So, you see, here I am.’

‘Yes … there you are. And here am I.’

There was silence between us in the loud room, each of us gazing at the other uncertainly. The woman was clearly put out by the whole puzzling situation. For, equally clearly, she was a confident woman, keen to control things, to win. Just like Katie.

‘I’m sorry. It must all sound rather crazy. You see, I’ve no idea …’ She left the idea hanging in the air, even more put out by her failure to bring it to earth.

‘Well, I wonder if you’ve made some mistake? If perhaps you misunderstood your father?’

She frowned again, bridling at this. ‘No. No, certainly not. I heard him perfectly clearly. And he wasn’t wandering at that point.’ She looked at me dismissively, with rather the same air of smug detachment that Katie used to assume when she was in the wrong, and wouldn’t admit it.

There was a chill impasse between us until, with a small sigh, she relented a fraction, but in a manner that suggested I was a tiresome child and she was only doing so because she was a guest in the house, and still needed to talk to me.

‘The point is,’ she said pedantically, ‘I’ve no idea why my father said what he did. He didn’t explain anymore: went all vague again … he’s on morphine. But it seems clear he knew your parents well. Yet neither of my parents – my mother’s dead – ever mentioned your parents to me, or you. So I don’t know what he was getting at. Yet it was obviously important to him that I went to your mother’s funeral, and met you.’

‘Well, I’ve no idea why, either. Though, of course …’ I saw my advantage here, but didn’t press it in my tone. ‘I might know your family, might know the connection, if you told me your family name. Your own name?’

The point struck home. She was put out again, and disliked the position even more this time. ‘I’m sorry. I should have introduced myself at the start.’ She was flustered. There was a scattiness about her that I liked, quite at odds with her previously controlled and schoolmistressy air. She had lost control for a moment.

‘I’m … I’m Elsa Bergen, from further back up the hill, behind the Vico Road. Georgian house. We’ve lived there for years, since my parents came here from Austria as refugees after the war.’

‘There’s a connection, then. My father was a refugee as well. Luchino Mario Contini,’ I said with something of a flourish. ‘Italian-Jewish – he died here last year. And my mother was Dublin Jewish. But Bergen – that’s not a Jewish name. Refugees from where?’

‘Not Jewish, no. Catholic. My grandfather, then my father, they had an antiques shop in Vienna before the war. Mostly religious stuff – the family was very religious. But the shop was destroyed in the bombing there and most of his family killed. Except his wife, my mother, Anna, who died two years ago. My father was away in the German army during the war, and he survived as well. After the war, since they’d both hated the Nazis, and there was nothing left for them in Austria, they wanted a new life somewhere. They came to Dublin eventually, helped by the Quakers, and my father started another antiques and art shop here and bought the house in Killiney. I suppose you might describe my father as a “Good German”.’

‘You said he was Austrian.’

‘More or less the same thing then, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes. You could say the same about my father. He was a “Good Jew” from what little I gathered of his life in Italy. But a stupid one. He and his family wouldn’t deny their faith or hide during the war and decided to openly tough it out. They were very assimilated Jews. They never thought their Gentile chums, or their friends in the fascist militia, would get around to arresting and sending them off to the death camps. They were wrong. That’s just what happened to them. In 1943, after Mussolini’s government collapsed and the Germans took over in Italy, the SS and their Italian buddies started to hunt out the Jews seriously. They got my father and all his family, in Pisa where they lived, and north at Carrara, and packed them off to a camp for Italian Jews at Modena, and from there to Auschwitz. My father was the only one of his family to survive.’

‘I’m sorry,’ she said simply, eyes blinking. She touched her nose, unconsciously, then smoothed the minute crow’s feet either side of her eyes. Mottled-green pupils set in wide white ovals, long dark eyebrows. Yes, mid forties, I thought. A little younger than me. Fresh, sober, sensible. No make-up or jewellery. A neat, sharply ridged nose, fine mouth, delicate lips, half-open, showing the pips of bright teeth, her mouth like a moist cut in an autumn fruit. Beautiful, in an open-air, the hell-with-fashion manner.

And then the sort of athletic body I liked, equally unfashionable in these anorexic times. The firm neck set on an unexpectedly short torso, well-set breasts, the narrowing waist running out to wide hips, a compact backside, the sense of sturdy legs below that. I’d like to have undressed her and started to paint her there and then.

‘Yes …’ I said, thinking. Then I pulled myself together and shrugged. ‘My father, his family – a sad story, among millions of other Jews. Though he soon recovered himself, did very well when he got to Dublin. Married my mother: she was from a rich Dublin Jewish family, bought this great mock baronial pile. All these terrible pictures …’ I gestured round the room. ‘That one, of my mother.’ I pointed to a large, 1950s chocolate-box portrait over the fireplace of a youngish, somewhat plump woman, in pearls with permed hair, made to look exotic in a billowy eau-de-Nil tea gown.

‘My father had that commissioned by some terrible Irish artist. And the rest …’ I swung my arm further round the room. ‘Russell Flint reproductions – Persian Slave Market and such like. And Alma-Tadema. There’s one over there of his I particularly dislike.’ I took her over to it. ‘Egyptian Morning at the Baths. But did you ever see a woman’s nude body look like Russell Flint and Alma-Tadema has them? Quite sexless. A woman’s body is full of awkward shapes and lengths, unexpected crevices and colours, flattish bits and slopes and little hillocks. That’s where the beauty is. And the sexiness.’ I turned and looked at her, nodding briefly, in open appreciation of the real thing.

She was put out by my gaze. ‘Well, I’m very sorry about your father.’ Wanting to change the subject even more, she continued, ‘Was he a businessman?’

‘Yes, but he was a civil engineer as well, before the war. He and his family owned the Contini marble quarries outside Pisa, and a larger quarry at Carrara, one of the famous white-marble quarries there. Mussolini was always wanting tons of stuff for his bloody great imperial buildings, so my father was exempted from military service, and that’s what he made his business when he got over here to Dublin after the war: importing marble from Carrara, for fireplaces, floors, pillars, tables and tombstones. The lot. No artistic taste, but he knew about marble. That big fireplace he had made over there for example: hideous design, phoney Gothic with those simpering, half-clad maidens at either side – it’s dreadful, but the marble’s wonderful. Carrara Cremo. Pure, veinless white. Hard but smooth as soap. Run your hand over one of the girls – go on, try it – the marble is just like the inside of a real woman’s thighs. Michelangelo used the same sort. Cut it himself from the same quarry in Carrara for his statue of David.’ Now there’s a realistic body for you! No coy underplaying of the muscles and genitals – the whole thing about to explode with power and sex.’

‘Well, I’m glad your father was so successful when he came here.’

‘Oh, he did very well when he met my mother. And you know what?’ I drank again. ‘She hasn’t left me a penny! Just all these awful pictures. The house and the rest of her money all goes to a Dublin charity. A cruel, mean woman.’

‘I see.’ She was cool, clearly shocked that I should so openly disparage my mother.

‘You’d understand my feelings if you knew how she treated me. I’m not trying to drown my sorrows for her, I can tell you. It’s someone else who’s just died on me. Rather knocked me out.’

‘I’m sorry.’ She made no further enquiries here. She fidgeted. She would have made her excuses and left, I’m sure, but for the unfinished business she had with me.

‘So,’ I said, ‘it seems our parents knew each other. Both our fathers refugees from the Nazis, and our families living not half a mile apart here in Killiney. Yet you and I never met, know nothing of the other’s family. Strange.’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m sure we’ll find the connection.’ I looked at her now without desire and a sober smile. ‘Some simple explanation.’

She didn’t return the smile.

‘I’m sorry.’ I put down my glass. The wine had brought me to the desired stage of forgetting Katie, or rather, it had brought me to the comforting belief that she was still alive and I was with her again. It was time to properly concern myself with this revenant. ‘I’m sorry to have been abrupt about my mother. I loved my father, but not her. She disliked me and bullied him, and I hate funerals, except for this part of them, the wake – and I usually come to enjoy that too much. Listen, I’m sorrier still not to have offered you any refreshment: Miss? Mrs? Ms?’ I looked towards the table where the drinks were, which I’d ordered from Mitchell’s in Kildare Street – on my mother’s account. ‘Gin, whiskey? Wine?’

‘“Miss” I suppose, if you have to put a handle to the name. But call me Elsa. Elsa Bergen, my family name. Though I am married, legally at least. Don’t even know where he is now …’ She stopped abruptly, annoyed at herself for disclosing too much personal information. ‘I’m sorry. I don’t know what I was on about. Yes, a glass of wine would be lovely.’

We pushed our way to the drinks table. I reflected on the rider she had added to her marriage. I turned to her. ‘No need to be sorry, is there?’ I asked.

‘About what?’

‘Your still being married. A common situation. Been mine, with my wife, for years.’ I didn’t add that this had been Katie’s situation, too, married for almost as long, to a man who’d behaved badly to her and long separated without her ever bothering to divorce him. I just said, ‘Divorce is such a bore, and so bad for the children. Who wants to put even more money in the hands of the bloody lawyers?’

‘Yes.’

‘Unless one wants to marry someone else.’

‘Of course.’

Her face had brightened, perhaps at this idea of happy second chances. We’d got to the big table. ‘There’s some good red wine. A Châteauneuf, or even better, a white Châteauneuf.’

‘A small glass of white would be lovely,’ she said judiciously. I poured her a glass, another for myself. ‘Canapés?’ I asked. ‘Awful word. Titbits is much better. Though you Americans say “tidbits”. The old puritan ethic. But you’re right, that was the original seventeenth-century spelling of the word in England.’ I picked up a dish, then another. ‘Some cheesy things, salami and anchovies, and olives. I love olives.’ I offered her a bowl of big, purply black Greek olives.

‘So do I!’ She was suddenly excited, picking up one delicately, but unable to restrain the wolfing enthusiasm with which she ate it. ‘Kalamata!’ she said joyously, as if the Mediterranean fruit had released all her earlier inhibitions, her cagey, decorous formality. She was indecorous now, putting a hand almost roughly to her mouth, voiding the stone but not putting it aside, gazing at it as if it were a jewel discovered.

‘I love olives.’

‘Have another one.’ I took one myself. She looked at me, startled, as if waking from another dream.

‘No. No, I won’t.’ Controlled again, reverting to her earlier mood.

‘Go on, for goodness sake, if you like them!’

She looked at me again, seeming to draw confidence and daring from my gaze. ‘All right, I will!’ She took another olive, then a third. ‘I’m sorry to be greedy.’

‘You’re not. Expected thing to be at an Irish wake … and thirsty.’ I raised my glass. ‘Happiness,’ I said. ‘I don’t care for “Cheers” or “Your health”. I’d prefer a good whack of happiness, whether I’m cheery or healthy or not.’

She raised her glass and took a fourth olive. Gorging on the juicy fruit, fingertips becoming purple, our rapport changed: we might have been old friends. People were pushing around us, chattering, she had to raise her voice. ‘I do have some excuse, being greedy with the olives. I’m doing a book about them.’

‘About olives?’

‘Yes, olives and olive oil. The history and culture of the fruit, the different lands and landscapes which nurture it, its culinary, medicinal and other uses.’

‘That sounds like the stuff they put inside the jacket.’

‘Yes, it is. Just that.’

‘Someone’s actually going to publish it?’

‘Yes, in New York. I’ve done several other books. I travel round different countries, meeting the chefs, the cooks, making notes. Then I write it all up when I get back. Travel, comment, cookbook.’

‘Tremendous!’ I meant it, but I could see she thought I was being ironic. ‘Where do you get back to?’

‘New York … I have an apartment there. With frequent trips over here since my father became ill.’

‘Well, we’ve all got to drop off the perch sometime. Make room for the rising generation. World’s chock-a-block already, isn’t it?’

I took another gulp of wine, swaying slightly. I realized she was astonished by this drunken, tactless comment. ‘I’m sorry, I’ve been under the weather recently. Forgive me.’

I shepherded her away from the crowd round the drinks table, towards one of the big mullioned windows looking over the bay. We stood there silently, looking over the bright summer view, the unexpected clump of palm trees at the end of the garden, the crescent beach with its bathers and deckchairs to the left, the boathouse with my father’s old motor cruiser, the Sorrento, inside to the right and the blue waters of the bay straight ahead.

‘It’s supposed to be like the Bay of Naples,’ I remarked, quieter now, ‘which is why my father wanted to live here. I’ve not seen the bay of Naples, but I bet the light would be quite different, and the colours. You’d get that whitish Mediterranean blue inshore, off the shallow rocks. Ultramarine, then deep Prussian-blue farther out. The headland over there – that’d be washed umber, a touch of bright ochre.’

‘You’re obviously a painter,’ she said abruptly.

‘Yes.’

‘What sort?’

‘Just paintings.’ I continued to study the view. ‘It’s funny – your father and mine, if they were old friends – they might have stood here, right at this window, years ago, looking at exactly the same view. I wonder what they were talking about?’ I turned and looked at her, blinking after the glare of sunlight coming off the water. ‘Strange to think of one’s parents, all the vast amount of things we don’t know about them. What they did before we were born, and afterwards, when we weren’t with them? It’s the supreme egoism of children, isn’t it, to think their parents only had a life when they were physically with them, playing or reading to them or whatever, when of course that was only the tip of the iceberg of their lives.’

‘I suppose so.’

We looked out to sea, yachts and dinghies sailing over the choppy water, whitecaps riding further out in the bay. I turned to her again. ‘So maybe there’s no simple answer about why your father told you to come to the funeral, what it was that I was to “explain” to you. But we could work on it.’

‘Yes, perhaps. We’ll see.’ She stalled. It was clear she didn’t want to work on it, wanted to cut her losses and get away from me.

A big man, a building contractor, a client of my father, interrupted us then. ‘Your dear good mother, Benjamin …’ He grasped my hand for several minutes, maudlin, full of phoney commiseration and bonhomie.

After I’d done with him I looked round for Elsa. She’d gone. Just upped and left. We hadn’t said goodbye, and there was still the mystery of our family connection to resolve. The way she resembled Katie – what did this mean? Was fate giving me a second chance? Did I want this? Katie had behaved appallingly and I surely didn’t want a repetition of that.

I suddenly wanted this new woman Elsa – this Jekyll to Katie’s Hyde. I’d contact her later – if I felt like it. Bloody rude of her, disappearing like that without a word. Just like Katie, I thought, so often vanishing in the middle of a meal or during an interval at the theatre. Contrary. I went back to the big table, refilled my glass, and set about provoking the other guests.

TWO

Later, with all the convivial mourners gone, I stumbled around, alone in the drawing room, a little drunk.

Taking an opened bottle of the white Châteauneuf I moved about the house, from one overstuffed room to another. Mostly heavy Victorian furniture, but some fine Gothic revival pieces as well. My father had liked the style and collected it from various antique dealers. There were several original William Morris pieces: a dining table and chairs, an oak cupboard in the hall, a chest of drawers, cabinets and other pieces upstairs.

I swayed up the wide polished oak staircase to the bedrooms on the first floor and looked into the rooms – the guest rooms, my father’s bedroom (in my memory my parents had always slept apart) where there was an extraordinary piece of furniture, a dressing-room toilet cabinet designed by William Burges, a splendidly quirky Victorian architect and furniture maker. The cabinet was delicately made, beautiful – largely done in pine, painted in red, yellow and black washes, with intricately worked brass fittings, cornerings and handles.

I opened it, displaying the rows of little drawers inside, pigeonholes, a mirror, various clever places for toilet knick-knacks, a cupboard below containing a chamber-pot, washbowl and jug, all painted with garlands of bluebells and daisies.

I pulled out one of the little drawers. A cut-throat razor, a decayed shaving brush, an old bottle of Collis Browne’s Tonic.

At the back of another drawer was a collection of small black-and-white photographs. My parents at the Dublin Horse Show years before. But then, beneath these, I came across something quite different. An older photograph. My father as a young man in an Italian army officer’s uniform, smiling, pleased with himself. I’d not known my father had been in the army and thought he’d been exempted. Then I noticed the pith helmet and the Africans.

Of course. This was before the war, Mussolini’s barbarous campaign in Abyssinia. My father had served out there, and here he was, at the head of a line of bedraggled, wounded and manacled Abyssinians. And my father holding the first of them, pulling him by a chain attached to his neck. I was surprised.

I went into my mother’s big bedroom looking out over the bright, early-evening light on the bay. I sat down on the canopied four-poster bed. There was a formal studio portrait on a bureau nearby. My parents shortly after they’d married, sometime in the early fifties. They were smiling at each other. Not like later.

My father, small with darkly brilliantined hair, neat moustache, suave good looks, very Latin; almost a caricature of an Italian. His chest puffed out, with the same aggressive confidence of the earlier African photograph, but matured, diluted in this later portrait by his dark bedroom eyes, softened with intimations of passion, warmth, even nobility.

Cruelty and warmth. The photographs reflected the extremes in his character. He’d been a man of extraordinarily varied and unsettled temperament. Quick to anger, with a ruthless edge to him, but then as quickly silent, as if stunned, when he became gentle and penitent, filled with tearful innocence.

His eyes in this photograph showed something else beyond the seductive Latin airs, the genial man about town with other Dublin businessmen, drinking gin and tonics in the old buttery bar downstairs in the Hibernian hotel. There were shadows in his eyes, the haunted look of a man who, at thirty, had seen and experienced the very worst in Auschwitz.

My mother, by contrast, showed a complete innocence in the studio photograph. A pleasant, round face, untouched by life. She was not like that later, when experience had laid hands on her. A face increasingly racked by pain and bitterness, vented often on me – I’ve never known why.

Taking the bottle I went up to the second floor where there was a long, glass-roofed landing with rooms to either side, guests’ and maids’ rooms years before. It was hot under the glass roof, where the sun had blazed down all through the long hot day. I sat on the floor, back against the wall, took the bottle, drank, closed my eyes and tried to laugh at my life.

I’d been a good all-round athlete at St Columba’s College, my school up in the Dublin mountains: a first-team cricket and rugby player, and I became a quick hand at boxing too, as a middleweight, taught by a burly cocksure ex-army sergeant, Johnny Branigan, who I had once surprised with a fast left hook to the jaw, stunning him for a moment, before he tried to do the same to me. After making a century in a cup match, I’d thought about becoming a professional cricketer with Middlesex. But when I was sixteen I fell in love with my father’s motor cruiser, the Sorrento, still moored in the boathouse, crewing it with my father in all sorts of weather, up and down the Irish Sea. The passion I came to have for boats then, thinking I might join the British navy, until I got the recruiting brochure and application forms, and felt the cold shadows of hierarchy, duty, restrictions – not the freedom of the seas.

Eventually I realized I was best of all at painting and sculpting. A gift for drawing and colour, and handling clay. The art master at St Columba’s encouraged me. So at sixteen I finally decided to be a painter. I remember the day in the art class when, annoyed at the general standard and leaning over a painting of mine, and in front of all the other boys, he said, ‘Contini here, you’ll never take a leaf out of his book. He has the gift, and you lot of pampered little jades don’t.’ The man was queer and fancied me as well as my work, but all the same he was probably right. I did have a gift. So I’d said to him, just to give cheek, ‘Yes, Sir, I’m going to be a painter!’ Then added for good measure, ‘And a sculptor.’ In fact, I was just an ambitious and aggressive schoolboy.

In any event my mother thought my being a serious painter was a hopeless idea, but my father encouraged me, paid my fees at the old College of Art in Kildare Street, and did the same later, financing me at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, where I studied painting and sculpture. My father was always keen for me to do well as an artist, and I liked him for that as much as anything. Now, thirty years later, I was still a painter – but blocked. Nothing decent done since the trouble with Katie brewed up two years ago. It used to be portraits and nudes, good stuff usually. Forceful, strong colours, the right lines and musculature. Paintings, and some commissioned sculpture, where there was nearly always more than the sum of the parts. That surprising extra – a hidden thought or sexiness in the sitter revealed, but in the art world now a painter scorned, with hardly a penny earned from my work in the last two years. I took another swig of the Châteauneuf.

I’d started out well enough after I’d left the Beaux-Arts, and stayed on in Paris. I’d soon come to sell my work well at a small Left Bank gallery. I’d begun painting in the manner of several artists. Something of Utrillo, then Soutine, Modigliani. School of Paris style. Street scenes, portraits, nudes. Particularly nudes. I’d been fascinated by women’s bodies ever since I was a child, about eleven, in bed with flu, and had a big Phaidon art book, Modern Masterpieces, which I’d found in the library. Halfway through there was an erotically reclining nude by Modigliani: it struck me with a blood-tingling sensation. I was startled by the provocative ease and availability of the woman, eavesdropping on her at a very private moment.

The picture stirred me sexually, so that I’d taken paper and traced it, my flu-fever seeming to increase the stimulation I took from it, copying it repeatedly, as if the better to possess every line and contour, every secret part of this marvellous woman. My mother found some of these tracings in my bed after I’d got up one day. She was shocked. ‘What’s the matter?’ I’d challenged her. ‘It’s a modern masterpiece. It says so on the cover of the book.’

Later on in Paris the lines of my work became more rounded, the colours softer and more varied – Pissarro and Bonnard became the great influences. Pissarro for his street and river scenes, Bonnard for his nudes.

The way Bonnard handled the flickering points of light in a bathroom, on the tiles, a mirror, the bath water, on the skin of his wife immersed in the mottled, green-blue, seemingly molten liquid. There was a hidden sexuality in the colourings and the vague composition that made the woman seem ethereal and unavailable, all the more desired.

Portraits and nudes. The first became my bread and butter, the second my passion – when I returned to London in the seventies and married Angela – living in London near Primrose Hill, where the two children had been born, Molly and Beatrice, before the marriage started to disintegrate.

Angela had eventually taken up with an older married lover, an architect in Yorkshire, who wouldn’t divorce and marry her. The usual story. She’d gone up to live near him in Yorkshire, where the two girls had gone to a Quaker boarding school that I’d paid for in those financially balmy years.

I rarely saw Angela now. Our relationship had drifted into indifference on her part and dulled incomprehension on mine. I’d never understood what she saw in the architect – a rather pompous, abrupt little man with a cracked front tooth, called Arthur. I always thought I had much more going for me.

I saw the two girls now and then: we were good, if rather distant friends. Molly, the elder at twenty and at university in Scotland, wants to be a forester. She has a boyfriend in the Highlands who works for the Forestry Commission. Beatty, two years younger, is still at the Quaker school doing A levels. Angela survives financially. A little money of her own and the lover subsidises her. Of course I should have divorced her years ago. She had behaved badly, running off like that with the shyster architect, but why divorce when no one else had come along whom I wanted to marry?

Until Katie, four years ago. I wanted to marry her all right. After three years of barely flawed happiness, I certainly wanted that. When I eventually asked her she said yes. The next day no, then finally chucked me, and then killed herself. Was it an accident? Perhaps the diary and scrapbook I found in her canvas bag will explain things. The bag she’d left last week, after I’d talked again about a proper future together, before she’d refused my offer and driven off without another word. A journal of some sort, when I’d looked at it briefly, but interleaved with dried wildflowers, Paris Metro tickets and the like from our country walks and trips abroad. An Album Consolatum, it might have been.

She’d had no need of this, I thought. She’d lived with me so tentatively and abandoned me so unexpectedly and completely a week before – why should she ever need to console herself for something she had never lost? She left me half an hour after we’d made love that summer afternoon – a last gift, and a permanent goodbye. I jumped into my old Bentley and followed her up the mile-long farm track that leads from my old barn in the Cotswolds to a small road at the top.

Near the top of the track I saw her car, rammed into the big beech tree in the flax field. By the time I got there the engine was on fire, flames licking up from the badly crushed bonnet. I thought she was dead, slumped over the wheel, the rim pressed into her chest. She wasn’t dead. She pulled herself back and opened her eyes, and then the engine began to flame viciously, fire starting to engulf the car.

The windows were closed. ‘Get out, for God’s sake! Open the door, the windows!’ She wouldn’t. She sat there, immobile, her hair starting to singe, the body I had made love with half an hour before being consumed by fire, incarcerated in the steel oven of the car.

I pulled at the door handle. I couldn’t open it. ‘Open the door, Katie! Open, push it!’

She wouldn’t, or couldn’t. Instead she turned her head, and out of the pall of smoky fumes that were beginning to envelop her, she looked at me dismissively in that silent way she had of saying no. Elusive, unpossessed to the last. I kicked at the door like a madman. I didn’t know if I was trying to save her or punish her, if I wanted her dead or alive, for I had come to hate her in these last years as much as I loved her.

I managed to get the door open at last and tugged at her, trying to drag her out, but she clung fiercely to the wheel, the flames leaping up from the dashboard, and my hair was beginning to singe. I had to retreat. ‘Get out, Katie, for God’s sake. Get out!’ I screamed.

Then I heard a shout behind me. I turned. It was Tom Phillips, my farmer landlord who lived at the head of the track, running towards me.

‘Quick!’ I said when he reached me. I had to save her life, which was mine as well, I realized, for I loved her then without reserve, knowing there might be only seconds left to save us both.

Tom and I, diving into the smoke and fire, finally managed to drag her out of the car. We were too late. Her dark hair was gone and only the stubbled, sooty crown of her skull was left. She was half-naked, her clothes burnt away, some still burning. Patches of the skin on her face had peeled away, displaying little volcanoes of bubbling, bleeding red – the fatty flesh of her breasts and biceps blistering, suppurating. She fell out of the car into the flax field, like a collapsed scarecrow, still smoking. And my last sight of her, before I had to turn away, was her face among the crushed blue flax, a happy-anguished face, seeing all that was special there for an instant, that particular nose that had rubbed mine, the small mouth that had kissed, the eyes that had seen, ears that had heard – all her senses that I had shared, the whole life that I had loved burnt out of her. The ambulance came and took her away. Tom took me back to his house, where I called one of Katie’s grooms at the riding school she owned, and told him what had happened – that Katie had been taken off to the hospital in Oxford. The groom, a taciturn fellow, barely responded, as if I’d just called to say she’d be late for tea. Since Katie hadn’t any close relations, I told the groom to call her friend, Monika – the only friend of Katie’s that I knew about – who lived next-door to the riding school. ‘Ask Monika to go to the hospital, deal with things,’ I told the man. Then I could speak no more. Katie was surely dead.

I stayed up at the farmhouse with Tom and his wife Margery. They gave me a tot of brandy and later a young policeman came to interview us. I told the man all that had happened, and Tom confirmed it. The policeman took our names and addresses, and Tom brought me back to my barn, where I started in on the drink; the last of some cooking brandy and a bottle of Bulgarian red, gone before Tom arrived down the lane again with a message from Sam McCartney in Dublin. My mother had died that afternoon. Would I come straight over? Tom said he’d drive me to Birmingham Airport the next morning. I could think of nothing but Katie then, anguished, the pain only beginning.

‘It must have been an accident,’ I said to Tom. ‘We’d had a row, so she drove away like fury, then skidded off the track and straight into that beech tree.’

‘I don’t know about an accident,’ Tom said. ‘The track is dead straight there, and firm. Nothing to skid on, and the beech tree is a good twenty yards off the track, the sun behind her, and the car almost new. You’d have to have had a real intention to drive into that tree.’

Maybe Tom was right. It hadn’t been an accident. It was suicide. After all, I’d seen her face, entirely conscious, scorning fate, making her own funeral pyre. That would have been very like her. Why should she kill herself just because I’d asked her for a proper life together? That was hardly a killing matter. If it was suicide there must have been some other reason. Only one thing certain – Katie was gone and all I had of her now were definitive memories.

Even when she was alive they often seemed definitive, since latterly I never knew if I was going to see her again. After weeks without seeing her – my only contact just an evening phone call now and then, when I’d try, and usually fail, to get through to her from the phone box beside the pub I went to near Chipping Norton, she would turn up out of the blue for sex in the afternoon, or sometimes for the night, and then disappear for another few weeks or longer.

I’d learned to be without her in any real sense. I lived alone and tried to bury myself in my work, painting furiously, each canvas worse then the last, and working on a nude sculpture of her in red Cornish clay.

My last good painting was of Katie, done over two years before, during our good times. I’d painted her lying naked in the foreground of the hazy, mauve-blue flax-flowered field beyond my barn, at the end of the long track, in the middle of nowhere.

I’d sold the painting for £6000, surviving for the last few years on the £4000 or so – after my dealer’s commission – that her naked body had fetched. The money was just enough for the rent, paint, canvases, smokes, drinks, food and petrol for the battered old green 1947 Bentley that I’d accepted instead of a fee for a portrait ten years before. I should have taken cash. I was running out of it even then, and I didn’t have enough to pay the rent of the flat in Primrose Hill, so that after Angela left I abandoned the flat and looked for something in the country.

I found the old barn by chance, travelling the north Cotswolds one day. I’d stopped at a pub in Chipping Norton and asked the landlord if he knew of anywhere to rent, an old barn or outhouse, as a studio. It was market day. He pointed to a sharp-faced, birdlike little man in a cloth cap sitting with a large jolly woman in the corner. ‘Ask him – Tom Phillips, local farmer. He might have something.’ He did.

I paid him only a nominal rent of £20 a month for the barn. Tom just wanted me to legally occupy the building to keep one of his scheming daughters and her husband at bay, who had started to convert the barn, assuming, wrongly, that her father was leaving her the place. His daughter had already installed an open staircase, half an upper floor and two large skylights, which made a fine north-facing studio.

I lived downstairs in the long open space, the birds high above me. Several pairs of immigrant doves came and went over the seasons and years, nesting way up in the rafters, flapping and warbling urgently in the spring, chuckling softly on dark winter days, a chorus of quiet ease, their white droppings and feathers coming to litter the floor like a strange snowfall – rafters from which I’d hung a battered chandelier, an old theatrical prop, made of gilded papier-mâché, heavily baroque, which I’d found in the local dump.

Downstairs there was a huge open fireplace at one end, flagstones and bare stone walls. A divan bed, tattered carpets, a sofa with the stuffing leaking out, some old armchairs, tables and bookshelves that I’d picked up at local sales or from the rubbish tip. There was electricity but no telephone, plumbing or water. I had to go out the back to a hand pump for that. No lavatory either. I used the ancient privy in a rackety wooden shed behind the barn.

Everything was basic in the barn. That was the thrill of the place – that it wasn’t a house, simply four bare walls and a roof, the long empty space downstairs a stage that I could make over entirely in my own images, moving the furniture about or just sitting there thinking of things, looking at the partly completed clay nude of Katie, drinking a glass or two of cheap Bulgarian red, listening to my Verdi CDs or an old Richard Tauber tape on my music centre and not worrying about the dirt. A roaring log fire in winter, cool within the great thick walls in summer. No sound but the wind in the corn, or the strange delicate swish of the breeze as it passed over the mauve-blue flax, moving across the hazy flowers in a long wave, the hand of God. Bright mornings of birdsong – crows in the beech trees, larks in the spring air. I love the place, though now and then I feel I could do with some company.

On winter Sundays I went up to the farmhouse and had elaborate teas with Tom and his wife Margery, the last of the old-fashioned farming people in the area. Great slices of breadcrumbed ham, cut from the bone, cold roast beef, horseradish sauce, Branston pickle, tomatoes and salad cream, all manoeuvred onto thick slices of fresh, crusty white bread, which Margery baked – the meal washed down with strong tea, laced with gin if you wanted it, for this was a traditional Sunday ritual of Tom’s. Sometimes as a result of these great whacks of gin in the tea, and having picked up logs in the yard and put them in the boot of the Bentley, I would take off down the lane in splendid state, singing ‘The Skye Boat Song’ loudly, the car swinging madly in and out of the ruts. Yes, a mad life lost in the wolds, and a fine madness when Katie was there.

She’d come regularly to the barn and spend nights and most weekends during the first three years of our affair, and I’d painted her time and again, summer and winter, portraits, nudes, sitting, standing, lying out on the low divan, pushed near the big fire in winter, naked in the warmth, her skin with a reddish tinge, coloured by the glowing logs.

Then things changed for her at home, and she came less and less often to the barn, then hardly at all, and didn’t care much to see me up at the stables either. I painted her only once after that, over a year ago, the nude of her lying at the edge of the flax field. After that she wouldn’t be painted, and my painting went to pot. I practically gave it up.

I took some more Châteauneuf, rolled myself a cigarette. So much for my various careers. The long struggle for good work seemed to have ended here, where it had begun thirty years before – upstairs, further upstairs, in this house. There was another, narrow stairway at the end of the landing, leading up to the attics. I got up and made towards it, climbing the steep stairs, sweating.

I’d made a studio for myself in one of these attic rooms when I was eighteen and first studying art in Dublin. I’d fitted it out in all the traditional ways as I’d seen them then: an attic with a skylight giving north light, dark drapes, a raised ‘throne’, big easel, a high stool, but I’d abandoned the place a year later after a flaming row with my mother and left for Paris.

I suppose my stuff was still up here. Nobody ever went up to these rooms. I moved along the narrow corridor, passing rooms filled with old furniture and lumber, until I reached my old studio at the end. I pushed the door open. The early-evening sun streamed through the cobwebbed skylight. The place was filthy, dust motes rising as I trod the boards. The throne was gone, but everything else was still there, including a stack of my old canvases in the corner.

I sat up on the high stool, right under the skylight, the sun beating down on me, the little room right under the slates an oven after the long day’s heat. I had another go at the wine, mopped my brow, and licked my salty lips.

My head started to swim.

Suddenly I was swaying, the stool tipping. I fell, sideways, smashing into the stack of old canvases against the wall, my head glancing off the stonework, stunned for a moment.

When I got my senses back my head was still swimming; my eyesight was blurred and my shoulder hurt. The room seemed almost in darkness now. I crouched up on all fours, trying to clear my head, looking at the wall where my old canvases lay scattered, some of the wooden stretchers broken. Gradually my vision cleared.

I got up and looked at the paintings. Only the stretchers of the front two or three were smashed. The other half-dozen oils at the back were all right. I picked through them. Tyro work, many of them nudes. Derivative, too influenced by Modigliani’s nudes.

Then I saw the picture.

It was at the back of the stack, unharmed. A nude woman, not a large canvas. The first thing I knew was that, though it was much in the Modigliani style, I hadn’t done it myself. The painting was far too good. The subtle colours of the woman’s face a darkish peachy tone, with touches of coral and orange that seemed to glow in the slanting beams of sunlight.

The body done in pink, light umber, lemon yellow, sitting on the edge of a divan, set against a dark maroon background, so that the lines and contours of her flesh stood out, were all the more sensuously apparent, the body vibrant, seeming to come out of the canvas at me. There was a fine symmetry in the placing of her arms, making angled parallel lines across the upper body, one hand at her crotch, the other touching the end of a blue beaded necklace. A young, dark-haired woman with a sad, almost tortured face, head cast down, eyes half-closed, as if she had just been, or knew she was about to be, abandoned by the painter.

The composition, colouring, the woman herself – with her angular set of head, long neck, oval eyes, mask-like face, breasts splayed to either side of one forearm – the whole thing was wonderful. In the style of Modigliani, or a copy. Though if the latter, I’d never seen the original in any book or gallery.