Great Scottish Speeches E-Book

9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

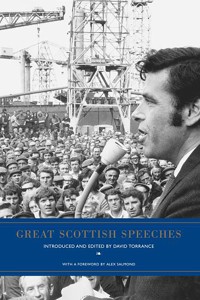

Some Great Scottish Speeches were the result of years of contemplation. Some flourished in heat of the moment. Whatever the background of the ideas expressed, the speeches not only provide a snapshot of their time, but express views that still resonate in Scotland today, whether you agree with the sentiments or not.Encompassing speeches made by Scots or in Scotland, this carefully selected collection reveals the character of a nation. Themes of religion, independence and socialism cross paths with sporting encouragement, Irish Home Rule and Miss Jean Brodie.Ranging from the legendary speech of the Caledonian chief Calgagus in 83AD right up to Alex Salmond's election victory in 2007, these are the speeches that created modern Scotland.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 360

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

First published 2011

eISBN: 978-1-912387-90-8

The paper used in this book is sourced from renewable forestry

and is FSC credited material.

Printed and bound by

MPG Books Ltd., Cornwall

Typeset in 10.5 point Gill and 10.5 point Quadraat

by 3btype.com

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Luath Press Ltd

Contents

Foreword by Alex Salmond

Preface by Prof David Purdie

Introduction

Calgacus • 1st Century AD

To robbery, slaughter, plunder, they give the lying name of empire; they make a solitude and call it peace.

Andrew Melville • 1595

There is Christ Jesus… whose subject James the Sixth is, and of whose kingdom he is not a king, nor a lord, nor a head, but a member.

Macbeth • 1611

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage.

Charles I • 30 January 1649

I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown; where no disturbance can be, no disturbance in the world.

Richard Rumbold • 26 June 1685

For none comes into the world with a saddle upon his back, neither any booted and spurred to ride him.

Lord Belhaven • 2 November 1706

None can destroy Scotland, save Scotland itself; hold your Hands from the Pen, you are secure.

Lord Balmerino • 18 August 1746

I was brought up in true, loyal, and anti-revolution principles.

Thomas Carlyle • 5 May 1840

The History of the World… is the Biography of Great Men.

Thomas Chalmers • 18 May 1843

We quit a vitiated Establishment – but we shall rejoice to return to a poorer one.

Frederick Douglas • 30 January 1846

If there was to be found a house open for him, he would yet raise the cry ‘send back the blood-stained dollars’

John Inglis • 8 July 1857

You are invited and encouraged by the prosecutor to snap the thread of that young life.

William Gladstone • 26 November 1879

Go into the lofty hills of Afghanistan.

Henry George • 18 February 1884

If I were a Glasgow man today I would not be proud of it.

Michael Davitt • 3 May 1887

Go in for what is your just and your natural right, the ownership of the land of Skye for its people.

Keir Hardie • 23 April 1901

Socialism proposes to dethrone the brute-god Mammon and to lift humanity into its place.

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman • 14 June 1901

When is a war not a war? When it is carried on by methods of barbarism in South Africa.

David Kirkwood • 25 March 1916

We are willing, as we have always been, to do our bit, but we object to slavery.

John Maclean • 9 May 1918

I am not here, then, as the accused; I am here as the accuser of capitalism dripping with blood from head to foot.

JM Barrie • 3 May 1922

Courage is the thing. All goes if courage goes.

Andrew Bonar Law • 19 October 1922

I shall vote… in favour of our going into the election as a Party fighting to win.

Lord Birkenhead • 7 November 1923

The world continues to offer glittering prizes to those who have stout hearts and sharp swords.

Ramsay MacDonald • 8 January 1924

Why will we take office? Because we are to shirk no responsibility that comes to us in the course of the evolution of our Movement.

Duchess of Atholl • 18 January 1924

Save the country from a Government which… I think the country has conclusively shown in the recent election it does not want.

John Wheatley • 23 June 1924

The bricklayer and the bricklayers’ labourers cannot afford to purchase houses which the bricklayer and the bricklayers’ labourers are building.

HH Asquith • 15 October 1926

Look neither to the right nor to the left, but keep straight on.

Rev James Barr • 13 May 1927

There is nothing better for an old Scottish song than that it should be sung over again.

Edward Rosslyn Mitchell • 13 June 1928

It connotes a journey, this one not from Lambeth to Bedford, but from St Paul’s to St Peter’s.

RB Cunninghame Graham • 21 June 1930

Nationality is in the atmosphere of the world.

Edwin Scrymgeour • 21 July 1931

When I see this sort of thing I say, God help me, I am for none of it!

Sir Compton Mackenzie • 29 January 1932

I believe that Scotland is about to live with a fullness of life undreamed of yet.

John Buchan • November 1932

I believe that every Scotsman should be a Scottish Nationalist.

Florence Horsburgh • 3 November 1936

It has never been done better by a woman before, and, whatever else may be said about me, in the future from henceforward I am historic.

George Buchanan • 10 December 1936

Talk to me about fairness, about decency, about equality! You are setting aside your laws for a rich, pampered Royalty.

Sir Archibald Sinclair • 3 October 1938

We may yet save ourselves by our exertions, and democracy by our example.

Winston Churchill • 17 January 1941

My one aim is to extirpate Hitlerism from Europe.

Thomas Johnston • 24 February 1943

I should like before I go from this place to offer some of the amenities of life to the peasant, his wife, and his family.

Robert McIntyre • 1 May 1945

Do we want education to breed a race of docile North Britons?

Sir David Maxwell Fyfe • 4 November 1950

We consider that our light will be a beacon to those at the moment in totalitarian darkness and will give them a hope of return to freedom.

John MacCormick • 8 January 1951

Recent events have emphasised that the Scottish still remember their past and are still determined to preserve their identity in the future.

John Reith • 22 May 1952

Somebody is minded now to introduce sponsored broadcasting into this country.

Robert Boothby • 19 February 1954

Homosexuality is far more prevalent in this country than is generally admitted.

George MacLeod • May 1954

I for one cannot press that button. Can you?

Wendy Wood • 30 May 1960

The Parliament of Scotland which God has miraculously preserved for us for 250 years.

Miss Jean Brodie • Novel published in 1961

I am a teacher! I am a teacher, first, last, always!

Jo Grimond • 15 September 1963

I intend to march my troops towards the sound of gunfire.

Malcolm Muggeridge • 14 January 1968

So, dear Edinburgh students, this may well be the last time I address you… and I don’t really care whether it means anything to you or not.

Edward Heath • 18 May 1968

We would propose…the creation of an elected Scottish Assembly, to sit in Scotland.

Mick McGahey • 1968

Nationalism in itself is not an evil, but perverted nationalism, which is really chauvinism, is a menace and danger.

Jimmy Reid • 28 April 1972

A rat race is for rats. We’re not rats.

RF Mackenzie • 1 April 1974

It is the comprehensive school that is on trial today.

David Steel • September 1976

The road I intend us to travel may be a bumpy one.

John P Mackintosh • 16 December 1976

It is not beyond the wit of man to devise the institutions to meet those demands and thus strengthen the unity of the United Kingdom.

Tam Dalyell • 14 November 1977

The devolutionary coach…will be on a motorway without exit roads to a separate Scottish State.

Pope John Paul II • 31 May 1982

There is an episode in the life of Saint Andrew, the patron saint of Scotland, which can serve as an example for what I wish to tell you.

Margaret Thatcher • 21 May 1988

It is not the creation of wealth that is wrong but love of money for its own sake.

Canon Kenyon Wright • 30 March 1989

Well, we say yes and we are the people.

Renton • 1990s

I hate being Scottish. We’re the lowest of the fucking low.

John Smith • 18 November 1993

Instead of going ‘back to basics’, the Government should be going back to the drawing board.

Very Rev Dr James Whyte • 9 October 1996

When someone dies young, as these did, we tend to think of what they might have been, of what they were becoming.

Jim Telfer • 21 June 1997

Very few ever get a chance in rugby terms to go for Everest, for the top of Everest. You have the chance today.

Donald Dewar • 1 July 1999

But today there is a new voice in the land, the voice of a democratic parliament.

Lord James Douglas-Hamilton • 16 December 1999

It is neither in keeping with the spirit of the times nor consistent with the social inclusion that we wish to celebrate in the year of the millennium.

Tommy Sheridan • 27 April 2000

For 300 years, those with power have had access to legal terror.

George Galloway • 17 May 2005

Senator, in everything I said about Iraq I turned out to be right and you turned out to be wrong – and 100,000 have paid with their lives.

Alex Salmond • 4 May 2007

Scotland has changed – for good and forever.

Endnotes

Foreword by Alex Salmond

SCOTS HAVE ALWAYS loved a good argument. We have a strong history and tradition of debate.

Indeed, a great compliment – and often challenge – to a fellow countryman or woman is to say that they have ‘a guid Scots tongue’ in their heid, and an obligation to make their voice heard.

So what some may describe as a national tendency to be disputatious, I prefer to think of as a commitment to speak up for what we think is right, to join in the discourse, and ultimately let the people decide.

And that is another aspect of our national character, the ‘democratic intellect’ – the strong belief that knowledge should be available to all, and that every citizen has the right to express their view without fear or favour, regardless of rank or station.

In Scotland, we have a shared and passionate commitment to the political and constitutional process as the determinant of change – which means that the force of argument decides what happens.

Therefore, as this book narrates, Scotland has always placed the highest value on the merits of a case – and its ability not just to persuade, but also inspire people to join a common cause.

And as this book also testifies, it is a tradition of our national story which reaches from the earliest times to the present day – and extends across the spectrum of political, religious, philosophical and scientific thought.

Throughout our history, we have had many different forums for national debate, as circumstances changed. Before our parliament was reconvened in 1999 after an adjournment of nearly 300 years, Scotland was nonetheless alive with passionate discourse on all sides and in many places – not least in the letters columns of our national newspapers!

It is an important part of our national life, and one that I hope this book helps foster. Public speaking can instil great self-confidence among young people, and we are blessed as a nation with so many talented young Scots with so much to offer – and with a guid Scots tongue in their heid.

As Scotland embarks on a new process of discussion and debate about our constitutional future, it is timely to celebrate the different voices and strands of opinion which have taken the nation to our present place – and to encourage new voices for our future progress.

Let the discourse begin!

The Rt Hon Alex SalmondMSP, First Minister of Scotland

Preface by Prof David Purdie

PSYCHOLOGISTS TELL US that neither the death of a parent nor the birth of a child, nor the beginning or ending of a partnership or love affair, is as terrifying to the generality of mankind than the looming requirement to give a public address. It need not be so. Great orators are few, but competence is within the reach of most people given adherence to the basics; especially the basic ability to get up, speak up and then shut up and sit down within the attention span of the audience.

In public speaking there are many rules and regulations but one – and only one – Golden Rule: Leave them wanting more. The finest compliment for an orator is to be told, collectively by ovation and individually by hearers, that they could have done with ten more minutes of that. So what makes a good speech? The question was first addressed by the greatest polymath of classical Athens, the Edinburgh of the South. Aristotle’s great Treatise, The Art of Rhetoric, set out ground rules which are as valid today as when he formulated them two and a half millennia ago.

A speech must do three things: It must educate; it must entertain and finally it must move the audience. Persuasive speaking requires another triad: the speaker must be seen to be a master of the subject; the emotional content must fit that of the audience – and the speech must flow seamlessly from a gripping start to a logical middle and to a valid conclusion.

Throughout the address, a really good speaker will engage with the audience through eye contact and gesture, having first prepared for the occasion by following the famous five steps. These were set out by Marcus Cicero, Rome’s greatest orator and writer on the subject: decide what to say; decide in what order to say it; decide the style of delivery; memorise it – and then deliver it. One other talent not possessed by all, but a huge asset if present, is the decoration of a speech with humorous anecdote and story. Scottish audiences particularly enjoy that magic mixture of education and entertainment when served up and garnished with the sauce of wit and analogy. All these ingredients you will find here in David Torrance’s deft selection.

The English and Scots languages are the most powerful weapons that can be placed at your command. But language, like any other weapon system, requires cleaning and oiling and repeated testing to be sure of accuracy in the field, or in this case, on the platform. Misdirected, it can cause serious injury, but when mastered it can cause pleasure almost without limit.

The very first orator in European literature was Odysseus, King of Ithaca. Homer tells us in the Iliad that he was not a massive physical presence:

But, when let that voice go from his chest,

And his words came drifting down like winter’s snows

Then no living man could stand against Odysseus.

In other words, he left them wanting more….

Prof David PurdieMD FRCP Edin. FSA Scot.

Introduction

THIS BOOK STARTED – unusually – as a status update on the social networking website Facebook. I posted the following on 15 November 2010:

David Torrance is on the hunt for Great Scottish Speeches (for a possible book pitch). Any ideas? The only criteria is that the oratory was delivered by a Scot, or in Scotland by anyone else…

Despite this rather vague invitation, within a few days more than 60 people had left comments, suggesting possible speeches and, in a few cases, simply remarking how stimulating the discussion was. Neil Mackinnon, for example, said it was ‘possibly the longest and most interesting Facebook status update comments list’ he had seen. Heartened, I collected these together, added some of my own, and took the idea to Gavin MacDougall at Luath Press, who enthusiastically took it on board. Enthusiasm from a publisher is a rare and therefore agreeable phenomenon!

Gavin was aware, as was I, of Richard Aldous’s excellent collection of Great Irish Speeches1, which had been a bestseller in, naturally enough, Dublin bookshops in the Christmas of 2007. I was already thinking of editing a Scottish equivalent when I ordered a copy of Aldous’s book online, but seeing it confirmed in my mind that if Ireland’s turbulent history could justify a book of speeches, then so could Scotland’s (admittedly less turbulent) past. As Aldous told me by email, his book attracted a lot of media attention, ‘primarily because it allowed everyone to turn it into a parlour game – what’s your favourite, what else should have been in/out, which person should have been in/out, etc’. I hoped mine would do the same, just as it had on Facebook.

Next came the criteria. Broken down, this fell into three parts. First, a speech had to be ‘Scottish’, which I took to mean – as per my original Facebook posting – speeches made by anyone (Scots and non-Scots) in Scotland or speeches made by Scots anywhere else in the world. (I’ll spare the reader a tortuous treatise on what precisely constitutes a ‘Scot’.) Next, and this may sound foolish, anything worthy of inclusion had to be classifiably a ‘speech’. In other words any piece of oratory that sources confirmed had been delivered by its author, and of any length from a paragraph up to several pages long (although for reasons of brevity, most of the speeches in this collection have been edited down – I hope sympathetically – to no more than four pages). Some did not qualify on this basis. Several people suggested Jenny Geddes’ interjection at St Giles’ Cathedral in 1637, but as it amounted to no more than a cry – ‘Deil colic the wame o’ ye, fause thief; daur ye say Mass in my lug?’2 – I had to leave it out, however significant it was historically.

Finally, each speech had to be ‘great’. Primarily, this came down to content; a truly great speech needs to say something, make an argument with coherence and brevity. It also needs to be well delivered, although in many cases content is more important than theatrical flourish; Sir David Maxwell Fyfe was not renowned as a great orator, but his speech at the signing of the European Convention on Human Rights in Rome was arguably historically important, and therefore ‘great’. A great speech also requires a contemporary context that heightened its delivery to more than just words on a page: a simple, memorable idea that somehow defined the moment. Great oratory, in short, needs to be authentic.

As I gathered material, I became more flexible. It seemed a shame, for example, to exclude fictional oratory, so my criteria was relaxed to allow room for speeches from the pens of William Shakespeare, Muriel Spark and, more contemporaneously, Irvine Welsh. A speech is a speech, be it fictional or real, imagined or intended. Few if any of those in this collection would not have been considered ‘speeches’ at the moment of their delivery.

Which speeches have made it to the final cut – and I gathered enough material for around 100 – is, of course, highly subjective, although I have striven for political balance, given that most speeches are political in nature. Thus there is, I hope, a good spread of rhetoric (and I don’t mean that in a pejorative sense) from Left and Right, Nationalist and Unionist. Some readers will inevitably start foaming at the mouth when they reach Margaret Thatcher’s 1988 ‘Sermon on the Mound’, but whether a speech is great or not does not come down to whether we like its speaker’s politics. I hope that even the Iron Lady’s most fervent critics could not deny the historical significance of her – after all sincere – oratory.

The process of tracking down the full texts of possible speeches was challenging, fun, time consuming and occasionally frustrating. With the exception of those delivered in the last few years (in which case the internet furnished me with the full text following a quick search), speeches, even contemporary ones, can be remarkably elusive. There are no Scottish suffragettes in this collection, for example, for although they gave hundreds of speeches at rallies across the country, contemporary newspaper coverage was paltry and subsequent scholarship incomplete.

Indeed, while I am on the subject of women, lest anyone consider me misogynistic, I am conscious that they are under-represented in this collection. I can only plead that the business of oratory is almost an entirely male category. Indeed, when The Guardian published a collection of great 20th-century speeches back in 2007, it obviously struggled to find female examples. The obvious explanation for this is that it was politicians who generally made speeches and, generally speaking, until recently Scottish politics was dominated by men.

Nevertheless, some have made their way into this collection, including the early female MP Frances Horsbrugh, the fictional Miss Jean Brodie and the robustly non-fictional Margaret Thatcher. As I have already mentioned, I searched in vein for extant speeches by Scottish campaigners for women’s suffrage, and was also frustrated in my hunt for oratory by early female political activists such as Helen Crauford, who made numerous speeches during the rent strike of 1917. Unfortunately, no one thought to preserve them.

This problem extended even to better-known, and more recent, speeches by men. Harry Reid urged me to include the educationalist RF Mackenzie’s plea for genuinely comprehensive education in 1974, observing that ‘surely’ someone had recorded his whole speech. Alas, they had not, and neither contemporary newspaper reports nor the Aberdeen Council archives gave me anything more than a few paragraphs. Even so, I pieced together what I could (including Reid’s contemporary Scotsman reports) and it is included within these pages.

Other fields – for example the sporting fraternity – simply have not made many significant speeches. I tried hard to include some footballers, rugby coaches, even golfers. But while I located plenty memorable quotes, there was simply no extended oratory. Likewise with writers, poets and artists. If they had spoken at all, it was on a political matter, and political speeches rather dominated in any case. Jim Telfer’s 1997 ‘Everest’ speech was an honourable, and very worthy, exception.

If I am making my task sound impossible, I do not intend to, for other speeches were remarkably easy to track down. Anything Parliamentary, for example, could be traced via the excellent http://hansard.millbanksystems.com website, which contains – in digital form – almost everything uttered in the House of Commons over the last couple of centuries. Similarly, modern orators tended to be modest enough to post transcripts of recent triumphs on their personal websites, for example www.georgegalloway.info. Indeed, Gorgeous George’s 2005 Washington performance is a fine example of a defensive or valedictory speech, echoing those made by others from the gallows, such as Lord Balmerino in 1746 and John Maclean in 1918. The difference, of course, is that today’s speakers – having vindicated themselves – tend not to be hanged.

Several interesting things occurred to me as I researched this book, such as the impact of certain speeches on public opinion. We may think that the art of oratory no longer has any tangible effect beyond the political fraternity, but when you consider Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman’s brave stand against the ‘barbarism’ of the Boer War alongside Tommy Sheridan’s speech against poindings and warrant sales almost a century later, it becomes clear that little, in some respects, has changed.

Indeed, talking of Sheridan highlights an important shift in the origins of significant oratory. ‘The essential ingredient of a great speech, a sense of injustice or outrage,’ observed the columnist Philip Collins in The Times, ‘began to dwindle as life got less and less outrageous in the back half of the 20th century.’ There is something in this, for as the austerity of the 1930s and ’40s gave way to the post-war boom, there was simply less to make impassioned speeches about. The firebrand Tommy Sheridan, however, believed that even in the year 2000 there was still a lot to be angry about.

I noticed other consistent features, not least the need for great speeches to project a social or political vision, from the utopian plea for a ‘Socialist Common wealth’ by Keir Hardie in 1901 to Thatcher’s very different ideological perspective at the Church of Scotland in 1988. There were also cultural differences. Two Rectorial addresses, for example, are included in this collection, a platform for great oratory that has not existed in the other three parts of the United Kingdom (or indeed Ireland prior to 1922).

A quick note on the chronology. The earliest speech included here is that reputedly given by Calgacus in advance of the Battle of Mons Graupius in AD 83 or 84, from which a misquotation – ‘they make a desert and call it peace’ – would certainly be known to the Nationalist Alex Salmond, whose speech following the 2007 Holyrood election is the most recent.

What almost 20 centuries of Scottish oratory highlights, above all, is the changing expectations of the listening audience, another crucial – and much underrated – requirement for a great speech. From speeches intended to rouse troops going into battle, to the more recognisable political, legal and religious oratory of the 18th and 19th centuries, and finally to those of the 20th century, encompassing wars both hot and Cold, and the constitutional debate.

One can only imagine what those listening to Calgacus made of his speech (if indeed it ever took place), while a glance at verbatim newspaper reports of 19th-century speeches – complete with notes of ‘Applause’ and ‘Laughter’ at key moments – indicates that audiences used to listen to complex political arguments for hours. As the 20th century wore on, what audiences expected to hear changed, and great speechmakers had to adapt. There were fewer public meetings, and therefore fewer public speeches, but in an increasingly mediadominated landscape speakers found other means by which to reach their audiences, and speeches became much shorter as a result. There is, however, one striking constant: the remarkable and enduring power of the spoken word.

Finally, a book such as this inevitably creates debts, so thank you to everyone who suggested, or helped me track down, speeches, including Keith Aitken, Professor Richard Aldous (for advice when I first started this project), Gavin Bowd, Rebecca Bridgland, Jill Ann Brown, Jennifer Dempsie, Robbie Dinwoodie, Michael Donoghue, Stuart Drummond, Rose Dunsmuir, John Edward, Tom English, Bradley Farquhar, Colin Faulkner, Neil Freshwater, Professor Gregor Gall, Tom Gallagher, Sam Ghibaldan, Martyn Glass, Duncan Hamilton, Martin Hannan, Malcolm Harvey, Professor Christopher Harvie, Gerry Hassan, Bill Heaney, Andrew Henderson, Martin Hogg, Professor James Hunter, Peter Kearney, Jacq Kelly, Hugh Kerr, Ed Kozak, Lallands Peat Worrier, Graeme Littlejohn, Danny Livingston, Andrew Lownie, Andrew MacGregor, Iain Mackenzie, Neil Mackinnon, John MacLeod, Maxwell MacLeod, Carole McCallum, Patrick McFall, Iain McLean, Michael McManus, Sarah McMillan, Lynne McNeil, Professor James Mitchell, Brian Monteith, Kenny Morrison, David Mowbray, Andrea Mullaney, Timothy Neat, Dr Andrew Newby, Willis Pickard, Harry Reid, James MacDonald Reid, David Ritchie, James Robertson, Jim Sillars, Graeme Stirling, Duncan Sutherland, DR Thorpe, Michael Torrance, the TUC Library, Alison Weir, Andy Wightman, Craig Williams, Mike Wilson, Donald Wintersgill, Canon Kenyon Wright, Jane Yeoman, Duncan Young and Eleanor Yule.

Please feel free to email me with suggestions for ‘More’ Great Scottish Speeches!

David Torrance

Edinburgh, July 2011

www.davidtorrance.com

Follow @davidtorrance on twitter

To robbery, slaughter, plunder, they give the lying name of empire; they make a solitude and call it peace.

Calgacus

1st Century AD

SPEECH REPUTEDLY GIVEN IN ADVANCE OF THE BATTLE OF MONS GRAUPIUS • NORTHERN SCOTLAND AD 83 OR 84

According to Tacitus, the senator and historian of the Roman Empire, Calgacus was a chieftan in Caledonia who fought the Roman army of Gnaeus Julius Agricola at the Battle of Mons Graupius in northern Scotland. The only historical source, however, in which he appears is Tacitus’s own Agricola, which describes him as ‘the foremost in courage and the noblest in birth’ of the Scottish chieftans. Tacitus also recounts the following short speech, the earliest in this collection, which he attributes to Calgacus.

The speech, often misquoted as ‘they make a desert and call it peace’, describes the exploitation of Britain by Rome in order to rouse Calgacus’s troops to fight. The site of this conflict, in which more than 30,000 native troops are supposed to have united in order to defend Caledonia (eastern Scotland, north of the Forth and Clyde), only to be routed by a numerically inferior Roman force, has yet to be conclusively identified, although it could have taken place between the rivers Don and Urie in Aberdeenshire.

The battle formed the decisive climax of Agricola’s governorship (AD 77/8–83/4) and seems to have broken resistance to Rome in the north of Britain for almost two decades, inaugurating a military occupation of most of what is now lowland Scotland.

Calgacus (sometimes styled Calgacos or Galgacus) is the earliest of only four named figures to feature in the history of Roman Scotland. Significantly, like the others, he bore a recognisably Celtic name, the equivalent of Calgaich, meaning ‘swordsman’ or ‘swordbearer’ – an element occasionally found in Irish Gaelic place names.

WHENEVER I CONSIDER the origin of this war and the necessities of our position, I have a sure confidence that this day, and this union of yours, will be the beginning of freedom to the whole of Britain. To all of us slavery is a thing unknown; there are no lands beyond us, and even the sea is not safe, menaced as we are by a Roman fleet. And thus in war and battle, in which the brave find glory, even the coward will find safety. Former contests, in which, with varying fortune, the Romans were resisted, still left in us a last hope of succour, inasmuch as being the most renowned nation of Britain, dwelling in the very heart of the country, and out of sight of the shores of the conquered, we could keep even our eyes unpolluted by the contagion of slavery. To us who dwell on the uttermost confines of the earth and of freedom, this remote sanctuary of Britain’s glory has up to this time been a defence. Now, however, the furthest limits of Britain are thrown open, and the unknown always passes for the marvellous. But there are no tribes beyond us, nothing indeed but waves and rocks, and the yet more terrible Romans, from whose oppression escape is vainly sought by obedience and submission. Robbers of the world, having by their universal plunder exhausted the land, they rifle the deep. If the enemy be rich, they are rapacious; if he be poor, they lust for dominion; neither the east nor the west has been able to satisfy them. Alone among men they covet with equal eagerness poverty and riches. To robbery, slaughter, plunder, they give the lying name of empire; they make a solitude and call it peace.

I have sure confidence that this day, and this union of yours, will be the beginning of freedom to the whole of Britain

In war and battle, in which the brave find glory, even the coward will find safety.

There is Christ Jesus… whose subject James the Sixth is, and of whose kingdom he is not a king, nor a lord, nor a head, but a member.

Andrew Melville

1545–1622

‘INTERVIEW WITH THE KING’ • FALKLAND PALACE • 1595

Andrew Melville was a university principal and theologian whose fame attracted scholars from across Europe to study at the Universities of St Andrews and Glasgow. He held the post of Rector at both of these seats of learning, but achieved added fame for campaigning to protect the Scottish Church from government interference. Although most accepted Melville was fighting to safeguard the constitutionally guaranteed rights of the Church, his critics believed him to be disrespectful of the monarch in the process.

In 1594 Melville was suspected by the King, apparently without foundation, of favouring the Earl of Bothwell, who had for a time supported Presbyterian objections to the King’s recent arbitrary and illegal behaviour. In 1595, and again in 1596, Melville made his famous ‘two kingdoms’ speech on the separate nature of the ecclesiastical and civil jurisdictions to King James VI of Scotland (later to become King James I of England) at Falkland Palace. It worked, for as one historian recorded, during the delivery of this ‘confounding speech his majesty’s passion subsided’.

Andrew Melville was born near Montrose in Angus, and educated at the Universities of St Andrews and Paris. After travelling in Europe he returned to Scotland in 1574 and was appointed principal of Glasgow University, and thereafter principal of St Andrews. Melville was also moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1578. Having annoyed the King, he was sent to the Tower of London for four years, and saw out the rest of his life in Sedan.

SIR, WE WILL ALWAYS humbly reverence your majesty in public; but since we have this occasion to be with your majesty in private, and since you are brought in extreme danger both of your life and crown, and along with you the country and the church of God are like to go to wreck, for not telling you the truth and giving you faithful counsel, we must discharge our duty, or else be traitors both to Christ and you. Therefore, Sir, at diverse times before I have told you, so now again I must tell you, there are two kings and two kingdoms in Scotland: there is King James, the head of this commonwealth, and there is Christ Jesus, the King of the church, whose subject James the Sixth is, and of whose kingdom he is not a king, nor a lord, nor a head, but a member. Sir, those whom Christ has called and commanded to watch over his church, have power and authority from him to govern his spiritual kingdom both jointly and severally; the which no Christian king or prince should control and discharge, but fortify and assist; otherwise they are not faithful subjects of Christ and members of his church. We will yield to you your place, and give you all due obedience; but again I say, you are not the head of the church: you cannot give us that eternal life which we seek for even in this world, and you cannot deprive us of it. Permit us then freely to meet in the name of Christ, and to attend to the interests of that church of which you are the chief member. Sir, when you were in your swaddling-clothes, Jesus Christ reigned freely in this land in spite of all his enemies: his officers and ministers convened and assembled for the ruling and welfare of his church, which was ever for your welfare, defence, and preservation, when these same enemies were seeking your destruction and cutting off. Their assemblies since that time continually have been terrible to these enemies, and most steadable to you. And now, when there is more than extreme necessity for the continuance and discharge of that duty, will you (drawn to your own destruction by a devilish and most pernicious counsel) begin to hinder and dishearten Christ’s servants and your most faithful subjects, quarrelling them for their convening and the care they have of their duty to Christ and you, when you should rather commend and countenance them, as the godly kings and emperors did? The wisdom of your counsel, which I call devilish, is this, that ye must be served by all sorts of men, to come to your purpose and grandeur, Jew and Gentile, Papist and Protestant: and because the Protestants and ministers of Scotland are over strong and control the kind, they must be weakened and brought low by stirring up a party against them, and, the king being equal and indifferent, both shall be fain to flee to him. But, Sir, if God’s wisdom be the only true wisdom, this will prove mere and mad folly; his curse cannot but light upon it: in seeking both ye shall lose both; whereas, in cleaving uprightly to God, his true servants would be your sure friends, and he would compel the rest counterfeitly and lyingly to give over themselves and serve you.

You are brought in extreme danger both of your life and crown, and along with you the country and the Church of God are like to go to wreck.

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage.

Macbeth

FICTIONALSOLILOQUY FROM THE PLAY MACBETH • 1611

The Macbeth of Shakespeare’s play was largely drawn from Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles, published in 1577. Holinshed had been heavily influenced by the writings of Hector Boece, who asserted, without any authority, that Macbeth had been ‘thane’ of Glamis and Cawdor, a styling then picked up by Shakespeare.

The unspoken conflict in this speech – one of the playwright’s great soliloquies – is that between free will and predestination, or in other words the King’s inability to overcome his darker temptations. The appearance of a bloody dagger in the air unsettles Macbeth, who does not know if it is real or a figment of his guilty imagination as he contemplates killing Duncan.

William Shakespeare was born in Stratford in 1564 into a relatively prosperous family. Details of his life are sketchy, although it is known he married at 18 and thereafter spent most of his time in London writing and performing his plays. He died in 1616.

MACBETH

Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee.

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?

I see thee yet, in form as palpable

As this which now I draw.

Thou marshall’st me the way that I was going;

And such an instrument I was to use.

Mine eyes are made the fools o’ the other senses,

Or else worth all the rest; I see thee still,

And on thy blade and dudgeon gouts of blood,

Which was not so before. There’s no such thing:

It is the bloody business which informs

Thus to mine eyes. Now o’er the one halfworld

Nature seems dead, and wicked dreams abuse

The curtain’d sleep; witchcraft celebrates

Pale Hecate’s offerings, and wither’d murder,

Alarum’d by his sentinel, the wolf,

Whose howl’s his watch, thus with his stealthy pace.

With Tarquin’s ravishing strides, towards his design

Moves like a ghost. Thou sure and firm-set earth,

Hear not my steps, which way they walk, for fear

Thy very stones prate of my whereabout,

And take the present horror from the time,

Which now suits with it. Whiles I threat, he lives:

Words to the heat of deeds too cold breath gives.

Art thou but/ A dagger of the mind, a false creation/ Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?

MACBETH

Wherefore was that cry?

SEYTON

The queen, my lord, is dead.

MACBETH

She should have died hereafter;

There would have been a time for such a word.

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown; where no disturbance can be, no disturbance in the world.

Charles I

1600–1649

SPEECH FROM THE SCAFFOLD • BANQUETING HOUSE • LONDON30 JANUARY 1649

Charles I (of England, Scotland and Ireland) is chiefly remembered for the English Civil War, in which he fought the forces of the English and Scottish Parliaments that had challenged his attempts to overrule parliamentary authority. Having been defeated, Charles was accused of treason by the republican victors and sentenced to death. His execution was set for early on the morning of 30 January 1649, although it had to be delayed while Parliament ensured it would be treason for anyone to proclaim a successor.

Charles prayed in the morning and dressed in two shirts so he would not shiver in the cold and appear frightened of his fate. The execution took place on a platform set against the wall of the Banqueting House on Whitehall (still standing), to which chains and manacles had been attached in case the King resisted execution. But showing considerable self-control, Charles not only remained calm but also delivered the following speech, in which he declared himself a ‘martyr of the people’. He then forgave his executioner, said some more prayers and gave the signal that was to sever his head from his Body.

Charles I (1600–1649), King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, was born in Dunfermline Castle on 19 November 1600 and baptised at the Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, the following month. He succeeded his father, James VI and I, as King in 1625.

ISHALL BE VERY LITTLE heard of anybody here… Indeed I could hold my peace very well, if I did not think that holding my peace would make some men think that I did submit to the guilt, as well as to the punishment; but I think it is my duty to God first, and to my country, for to clear myself both as an honest man, and a good King and a good Christian.

I shall begin first with my innocence. In troth I think it not very needful for me to insist upon this, for all the world knows that I never did begin a war with the two Houses of Parliament, and I call God to witness, to whom I must shortly make an account, that I never did intend for to encroach upon their privileges, they began upon me, it is the militia they began upon, they confess that the militia was mine, but they thought it fit for to have it from me.

I could hold my peace very well, if I did not think that holding my peace would make some think that I did submit to the guilt.

God forbid that I should be so ill a Christian, as not to say that God’s judgments are just upon me: many times he does pay justice by an unjust sentence, that is ordinary: I will only say this, that an unjust sentence that I suffered to take effect, is punished now by an unjust sentence upon me, that is, so far I have said, to show you that I am an innocent man.

Now for to show you that I am a good Christian: I hope there is a good man that will bear me witness, that I have forgiven all the world, and even those in particular that have been the chief causers of my death: who they are, God knows, I do not desire to know, I pray God forgive them.