Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

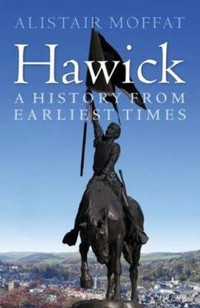

As Hawick celebrates the 500th anniversary of the fight at Hornshole, the first stirrings of the defining traditions of the common riding, Alistair Moffat takes the narrative much further back into the mists of prehistory, to the time of the Romans, the coming of the Angles and the Normans. He recounts how Hawick got its name, where the old village stood, who the early barons of Hawick were and then charts the amazing rise of the textile trade, bringing the story right up to the present day. Beneath the familiar streets and closes lies an immense story - the remarkable and unique story of Hawick. If this book shows anything, it shows that Hawick has changed radically over the many centuries since people began to live between the Slitrig and the Teviot. All that experience in one place has created and invented much and the future will turn for the better for a simple reason. Hawick's greatest invention is her people.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 367

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HAWICK

This eBook edition published in 2014 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Alistair Moffat 2014

The moral right of Alistair Moffat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 229 0

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 807 0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

For Ellen Irvine

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Introduction – The Irvines

1

Hornshole

2

Hawick among the Hills

3

Aye Defend

4

The Coming of the Wolves

5

The Lords of the Names

6

Cornets, the Common and Carterhaugh

7

Hardie’s Hawick

8

Hawick Lost and Found

Index

Also Available

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

The Mote, photographed in 1912

Auld Mid Raw, demolished in1884

Hawick Common Riding, 1902, led by Cornet William N. Graham

Hawick Railway Station, 1903

A cavalry regiment at Stobs Camp, 1904

Stobs Camp Post Office and a group of regimental postmen, 1905

The unveiling of The Horse by Lady Sybil Scott in June 1914

The 400th anniversary celebrations of Hornshole in 1914 at the Volunteer Park

The Chase

An autographed portrait of the great Jimmy Guthrie

Manly support – made in Hawick

Jimmy Guthrie’s characteristic riding style

Jack Anderson, Hawick and Scotland, Huddersfield and Great Britain

Hawick RFC, Border and Scottish Champions, 1959–60

Bill McLaren

The Mote, photographed in 1912

Auld Mid Raw, demolished in 1884

Hawick Common Riding, 1902, led by Cornet William N. Graham

Hawick Railway Station, 1903

A cavalry regiment at Stobs Camp, 1904

Stobs Camp Post Office and a group of regimental postmen, 1905

The unveiling of The Horse by Lady Sybil Scott in June 1914

The 400th anniversary celebrations of Hornshole in 1914 at the Volunteer Park. Miss Margot Barclay, ‘the Queen of the Borderland’, is drawn in her ‘car’ by 21 pages

The Chase

An autographed portrait of the great Jimmy Guthrie

Manly support – made in Hawick

Jimmy Guthrie’s characteristic riding style

Jack Anderson, Hawick and Scotland, Huddersfield and Great Britain. The only Scot ever to score two tries against the All Blacks

Hawick RFC, Border and Scottish Champions, 1959‒60

Bill McLaren

INTRODUCTION

THE IRVINES

‘AYE DEFEND!’

Startled, I looked up at my mum in terrified astonishment.

‘Aye defend your rights and Common!’ she shouted as the Cornet raised up the banner and the High Street crowd roared its support.

My mum never shouted at home in Kelso – not even when she had cause, usually supplied by me. A gigantic, snorting horse suddenly clattered sideways and I skittered behind her. But she cheered all the more and muffled, from somewhere, I could hear, ‘Hip, hip, hooray! Hip, hip, hooray! Hip, hip, hooray!’ The riders and the flag moved on, the crowd followed and I stopped clutching my mum’s hand so tightly.

When she came home to Hawick for the Common Riding, my mum became a different person. Although I did not understand it at the time, she came home every summer to be herself again – a Teri (a native of Hawick), a sister, a cousin, a niece, a girlhood friend and not just a mother. Born Ellen Irvine at Allars Crescent when it was a bowed row of tenements behind the west end of the High Street, she had seen Cornets raise the banner high only yards away from where she had grown up. The summer colour of the rideouts, the songs, the chase, the Mair and the shows at the Haugh were bright threads woven into her earliest days. One of seven sisters and a solitary brother, my mum was raised in a tiny flat, in the body warmth of a crowded, noisy and vivid family. Seventy years later, when my dad died, her bewilderment was more than emotional. She told me it would be the first time in her life she had not shared a bed.

At the Common Ridings, I inherited a powerful sense of the closeness of the Irvines. My aunties Mary, Jean, Daisy, Isa and Margaret and my uncle David all gathered at the Mair, always spreading out rugs and a vast picnic at what seemed to be exactly the same place. Even the ghost of Auntie Mina, who died before we could know her, seemed to linger there. In the June sunshine, we celebrated. With all my Hawick cousins, there must have been thirty or forty eating sandwiches, drinking lemonade or something stronger, watching the races, the purples, yellows, reds, blues and greens of the jockeys’ silks shining in the sun, the rumble of hoof beats, the cheering crowds, my aunties shaking their heads at one or two neighbours who had celebrated too well and appeared to have lost control of their legs.

In those distant summers of the 1950s and early 1960s, Hawick seemed to me a wonderland of generous laughter and music. Exotic too – the shows at the Haugh smelled of spun candyfloss, hot dogs and onions, and in the air was the faint, electric whiff of disrepute. I loved it. My uncles often gave me a half-crown so that I could go on the dodgems or the Waltzer or shoot tiny, feathered darts out of ancient rifles with bent barrels. As the men jingled change in the pockets of their flannels – their tweed sports jackets, Van Heusen shirts and club ties immaculate – and the women wore new dresses, it occurred to me that Hawick people had come to their own party. There was a sense of a long celebration punctuated by mysterious rituals everyone understood, gatherings at specific places at specific times and a simple pride. Hawick was all dressed up to celebrate no more and no less than itself.

There was also a palpable sense of escape. From the deafening rattle and clack of the mills where most of my aunties worked, they were released into the June sunshine for the Common Riding. The mills fell silent then but, for the rest of the year, they meant money and, more significantly, money for women, who were in a large majority on the dozens of weaving and knitting flats. Nimble fingers, a keen eye and an uncomplaining attitude to the endless repetition of textile production had delivered jobs in abundance for women. When I began to go to Hawick Common Riding with my mum in the mid 1950s and into the 1960s, there was money in Hawick and most of it in purses and handbags rather than wallets and back pockets.

Although I did no more than intuit it at the time, Hawick women, and especially Irvine women, were vivid, even exuberant. ‘Weel pit oan, like maist Hawick folk, and aye plenty to say for theirsells’ was my dad’s description and, with the help of exclusive access to the mill sales, there was plenty of cashmere and high quality tweed on view at the Mair and the grand occasions of the Common Riding.

Hawick women also had an independent, adventurous streak. My auntie Jean was holidaying in Majorca long before the arrival of the package tourists and she even had a special, posh wee handbag-like thing she kept her fags in. Never afraid to speak her mind, if she could get a word in edgeways with her sisters, Jean also had a stock of risqué stories that came straight out of the mills. Much enhanced by the relative prosperity in the manufacture of knitwear, hosiery and tweed, the status of women in Hawick was high. I remember all my uncles very fondly but they are snapshots in black and white while my aunties lived in vivid Technicolor.

Compared to douce, well-set Kelso, essentially a market town in the 1950s serving the rich farmlands of the lower Tweed Valley, Hawick seemed metropolitan. When we stayed with Auntie Jean at her flat at the top of Gladstone Street, we went out to the pictures – almost every night. Not only was there a rapid turnover of films at the Kings and the Piv (I had to look this up, The Pavilion, long disappeared, was its Sunday name), they were shown on a continuous loop. This amazed me. You only had to pay once and you could watch everything at least twice. More amazing, my mum and my auntie Jean took me and my sisters into a film halfway through – and then we waited for it to start again so that we could see how it began. I can remember blue cigarette smoke curling upwards through the beam of the projector. And then my mum would get to say, ‘This is where we came in.’ and we would leave. Usually I managed to persuade a detour to the chip shop in Silver Street, if we were at the King’s, or a visit to Taddei’s Cafe in the High Street. It was famous because my cousin Carl once knocked over a big glass container of peanuts and it smashed on the floor.

Hawick’s sense of otherness, of being different from its neighbouring Border towns was of course heightened by language. Yow, mei, sei and hyim were immediately recognisable to me as ‘you’, ‘me’, ‘see’ and ‘home’ because that was how my family spoke. Not strange or difficult, it was the language of warmth, celebration, good jokes, relish and directness. Relish and directness because the Hawick accent encourages full value for every syllable, nothing is glossed over, literally, and its insistence is total. When my cousin Janet announced that she did not much care for me – ‘Hei is horreebull!’ – no doubt was possible.

Men asserted themselves mightily in one huge aspect of life. Rugby was dominant in the Borders in the 1950s and 1960s. And rugby was the only thing I didn’t like about Hawick. They won all the time. And reared, but never sated, on season after season of unremitting success, Hawick rugby crowds could be tribal. If, by some rare refereeing mischance, Hawick were knocked out of a Borders sevens tournament, the terraces thinned dramatically as the Hawick fans simply went home. At the end of the 1960s, I played for Kelso against Hawick in a couple of tournaments and, while the players had the confidence of repeated success (they won both ties), the crowd was nevertheless visceral. When I tackled a Hawick player on the touchline at Riverside Park and momentum carried us skidding to the feet of the packed crowd, a voice hissed, ‘Dirty Kelsae bastard.’ and another spat at me. Only eighteen, I was taken aback.

Probably wisely, my mum never came to see me play. But she could be quietly fierce about things that really mattered and, looking back now, I can see that her independent strength of will and mind had much to do with her upbringing. My mum deferred to no one, believed that no one had any right to call themselves better. Richer certainly, better educated probably, taller obviously, but never innately better. That belief in a fundamental egalitarianism developed into an equality of regard. Everyone, no matter how humble or exalted their circumstances, had the right to an equality of regard and my mum never wavered from that. In her eyes, dustmen and dukes deserved respect that was theirs to lose.

Much of her sense of herself and other people sprang from her utter decency and enveloping warmth but some of it was also learned as she grew up in Allars Crescent in the 1920s. ‘Aye defend your rights and Common!’ was shouted with conviction for my mum believed it, believed in the fundamental democracy of a community of ordinary people lining their streets to hail one of their own as he passed with the town standard, the emblem of that democracy, in his working man’s hand. Like many of the Border principals, Hawick Cornets are chosen precisely because they are ordinary citizens who have demonstrated a simple love for the place where they were born. And, from that central, irreducible feature, the commonality of the Common Riding flourishes. It is a celebration of Hawick and everyone in it, regardless of status or money. All you have to be is a Teri. And my mum first imbibed that sense of simple democracy as a child and grew into a woman who believed in it absolutely.

Despite all of the reverses, closures and failures of recent years – even the humbling of the great rugby team – the flame of the Common Riding still burns brightly. All that it symbolises still lives and thrives in Hawick. It remains a remarkable, utterly different place and its story is never less than fascinating. My mum, Ellen Irvine, never lost her love for the town and never misplaced its values. I am honoured to be her son and, in inadequate thanks for all the love she gave me, this book is dedicated to her memory.

Alistair Moffat, January 2014

1

HORNSHOLE

WHEN DAWN broke on the morning of 10 September 1513, the landscape of hell was revealed. On the gently undulating northern ridges of Branxton Hill, more than 10,000 men lay dead or dying. In the midst of the carnage were the naked, plundered bodies of King James IV of Scotland, Alexander Stewart, Archbishop of St Andrews, George Hepburn, Bishop of the Isles, two abbots, nine great earls of Scotland, fourteen lords of parliament, innumerable knights and noblemen of lesser degree and thousands of ploughmen, farmers, weavers and burgesses. It was the appalling aftermath of the Battle of Flodden, the greatest military disaster in Scotland’s history.

In the grey light of that terrible dawn, sentries posted around the captured Scottish cannon could make out where the brunt of battle had been joined. Below them, at the foot of the slope, ran the trickle of a nameless burn now piled with slaughter, a wrack of bodies, obscenely mangled, broken pike shafts, shattered shields and everywhere blood and the sickening stench of death, vomit and voided bowels. Not all of the bodies were yet corpses. Through a long dark night, the battlefield had not been a silent graveyard. Trapped under lifeless comrades, crippled, hamstrung or horribly mutilated, fatally wounded men still breathed. Bladed weapons rarely kill outright and they were often used to bludgeon men to their knees or into unconsciousness. In the churned mud of the battlefield, some men will have lost their footing, fallen and been hacked at before they could get up. Many bled to death, maimed, lacerated by vicious cuts, screaming, fainting and screaming once more in their death agonies. Some will have been put out of their misery by parties of English soldiers scouring the field by torchlight for plunder but others will have lingered on in unspeakable pain, praying to their god, passing in and out of consciousness. The fury of the battlefield may have been stilled and Flodden Field awash with death and defeat but all was not yet over.

In an instant, the plunderers looked up and the sentries by the cannon stood to, clutching at their weapons, frantically peering through the morning light. They could hear the rumbling thunder of hoof beats – and then suddenly riders erupted over Bareless Rig. With 800 horsemen at his back, Lord Alexander Home galloped hard across the horrors of the battlefield and up the slopes of Branxton Hill. They had not come back to Flodden to rejoin a lost battle but to rescue their captured ordnance. And they very nearly succeeded. After a sharp skirmish, the English gunners managed to load and get off a volley at Home’s squadron and they scattered.

And so it ended. And the Border horsemen wheeled round and raced out of range. To the north, having crossed the Tweed by the morning of 10 September, the remnants of the defeated Scottish army limped homewards. There appears to have been no organised pursuit for, although between 5,000 and 8,000 Scots had been killed at Flodden Field, the Earl of Surrey’s army had also taken severe casualties. But those Englishmen who fell were, for the most part, ordinary foot soldiers. King James himself led the downhill charge of his own battalion, running towards the enemy, and most of his noblemen did the same. They led from the front and, when the grim scrummage of hand-to-hand fighting went against them, the king, his earls and his knights were amongst the first to be cut down and killed, unable to retreat, trapped in a murderous, fatal vice. By contrast, the Earl of Surrey and his captains had stationed themselves behind their lines and could direct the flow of the battle, making judgements, issuing orders. Submerged in the ruck of the front rank, James IV and his earls were impotent and, having become foot soldiers able to see only what was directly in front of them, they left the huge Scottish army leaderless. It was a critical, determinant distinction between the two sides.

Lord Home and the Earl of Huntly were in command of the battalion on the left wing of the Scottish army and were the first to engage. The Border pikemen and Huntly’s Highlanders drove through the English ranks and a rout was only prevented when the Cumbrian baron Lord Dacre ordered his cavalry to charge into the melee. But, when the king’s massive battalion of 9,000 men locked with the centre of Surrey’s forces and the English billmen began to turn the battle into butchery, Home and Huntly became detached. Able to rally their men on the higher ground to the south-west, they saw that history was moving below them, turning against Scotland. In the rear of the Scottish battalions, the less well-armed, less disciplined and much less motivated ordinary soldiers could see the Scottish pikes falling in front of them and their lords and captains going down with them. Many turned away and fled, following Home and Huntly as they led their men off the field in some order. Many Borderers will have gone with them, saving themselves from the slaughter.

Douglases fell at Flodden. In the front rank, Sir William Douglas of Drumlanrig, Baron of Hawick, was hacked to death by the billmen. It is said that two hundred of his kinsmen were killed by his side. While there exists no firm documentary evidence to corroborate this tradition, a similar fate certainly befell William Hay, the Earl of Erroll, and his retinue. Eighty-seven Hays died with him. Flodden devastated Scotland’s noble families and, while many ordinary soldiers were cut down (amongst the battalion of Highlanders led by the Earls of Argyll and Lennox, there was great carnage when they were attacked by English archers), it seems likely that Borderers did not suffer as badly as traditions – and music – insist.

I’ve heard the lilting, at the yowe-milking,

Lassies a-lilting before dawn o’ day;

But now they are moaning on ilka green loaning;

‘The Flowers of the Forest are a’ wede away.’

Jean Elliot’s lyrics of 1756 imply that Flodden saw many Border flowers ‘wede away’ and the ancient air is played at the Casting of the Colours at Selkirk Common Riding each year when it is understood as a lament and a commemoration of the battle. While many Borderers were undoubtedly killed, the association may well be overstated.

It was Scotland’s auld alliance with France that induced James IV to invade England and thereby open up a second front while Henry VIII was campaigning across the Channel. But less than a year after Flodden, England made peace with France and French support for Scotland ceased immediately. Without any consultation or even fore-knowledge, the treaty included Scotland by expressly forbidding any raiding into England – but not English raiding into Scotland. By the standards of any age, it was a cynical sell-out – the abandonment of an ally so recently devastated in a battle fought in a common cause.

In the winter months of 1513 and a year later, in 1514, several English raiding parties were reiving cattle and burning farms in Tweeddale and Teviotdale. Aside from the skirmish at Sclaterford on the Rule Water near Bonchester Bridge in November 1513, few reports of incidents have found their way into the historical record but there is no doubt that serial mischief took place in the aftermath of the great slaughter. While the armies clashed at the foot of Branxton Hill, Scottish and English thieves, the forerunners of the Border Reivers, had attacked the English camp at Barmoor, two miles to the east. According to a contemporary chronicler, ‘Many men lost their horses, and such stuff as they left in their tents and pavilions, by the robbers of Tynedale and Tweeddale.’

For exhausted soldiers who had survived and won a bloody battle, their return to a plundered camp would have left a bitter and lasting taste. It may be that a year later some would ride back into the Scottish Border country in search of revenge. But one particular party of English raiders in one particular place would be disappointed.

Under the patronage of Lord Thomas Dacre, the Cumbrian baron whose cavalry had driven off Home and Huntly the year before, a group of raiders had been encouraged to take advantage of the victory at Flodden. In 1514, Dacre sent a despatch to Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII’s principal minister saying, ‘There was never so much mischief, robbery, spoiling and vengeance in Scotland as there is now, without hope of remedy, which I pray our Lord God to continue.’ And it did. A party of English horsemen had corralled a pack of stolen beasts at Hornshole, on the banks of the Teviot two miles east of Hawick. The place name probably derives from Heron’s Hole, a favoured fishing-place for those elegant birds once memorably described as Presbyterian flamingos. Other possible meanings are Orm’s Hole, after the same Anglian lord who gave his name to Ormiston, or Orm’s Tun. Less likely is Hornie’s Hole, a deep dwelling place for the Devil – although diabolical doings are an understandable association with the times local people were living in. Perhaps the advancing English raiders planned to assault the village and the farms around that stretch of the Teviot. A powerful oral tradition recounts that a party of young men from Hawick mustered and, at night, attacked the enemy encampment. Called ‘callants’ (an unusual term, cognate to the Latin verb calere, ‘to warm’, and probably carrying the sense ‘hotheads’), they are said to have scattered the raiding party and captured their flag.

Where documentary history is silent or lost, the imagination of the great Hawick poet, James Hogg, rushed in to fill the vacuum. Here is his description of events at Hornshole followed by the rousing chorus of ‘Teribus’:

All were sunk in deep dejection,

None to flee to for protection;

Till some youths who stayed from Flodden,

Rallied up by Teriodin.

Armed with sword with bow and quiver,

Shouting ‘Vengeance now or never’,

Off they marched in martial order

Down by Teviot’s flowery border.

Nigh where Teviot falls sonorous

Into Hornshole dashing furious,

Lay their foes with spoil encumbered;

All was still, each sentry slumbered.

Hawick destroyed, their slaughtered sires –

Scotia’s wrongs each bosom fires –

On they rush to be victorious,

Or to fall in battle glorious.

Down they threw their bows and arrows,

Drew their swords like veteran heroes,

Charged their foe with native valour,

Routed them and took their colour.

Now with spoil and honours laden,

Well revenged for native Flodden,

Home they marched, this flag displaying –

Teribus before them playing.

Teribus ye Teri Odin,

Sons of heroes slain at Flodden,

Imitating Border bowmen.

Aye defend your rights and Common.

Much has been made of this incident – indeed, some would argue that the complex traditions of Hawick’s Common Riding are built on it. Encouraged by Hogg’s skill, there is a widely held belief that the young callants or hotheads were somehow taking revenge for ‘the sons of Hawick who fell at Flodden’ and that the village and surrounding area had been emptied of older men – those who had died in battle a year before.

Much more likely is that many of the local lairds had been killed – the Douglases of Hawick and Cavers had certainly suffered loss but other notables had as well – and, in military terms, the community lacked leadership. It is important to grasp what this meant. As Baron of Hawick, Sir William Douglas owned the village (it was not yet a town) and much of the land around it. The inhabitants owed him services – almost all of them related to food production of one sort or another. Douglas had absolute power over his tenants and he would not have hesitated to assert it by force. Equally, he and his household would have protected their assets, the village and the neighbouring farmland, by force. But, in 1514, it is very likely that central authority in Hawick, Cavers and elsewhere had been cut to pieces on Flodden field and whoever was left in Drumlanrig’s Tower was female, very young or too powerless to take any initiative.

In these unusual circumstances, a much more attractive interpretation of the events that led to Hornshole suggests itself. Instead of cowering, waiting for the attack or fleeing into the hills, the callants acted on their own initiative to protect their people and what property they had. Without the need for aristocratic direction, they acted together in the common interest – aye defend your rights and Common! It was the beginning of a long, proud and immensely impressive tradition of Hawick helping herself.

2

HAWICK AMONG THE HILLS

ON THE ROCKY western coast of the Isle of Man near the hamlet of Niarbyl, the cliffs of a secluded cove have preserved something unique – the key to understanding the geology and the landscape of the Borders. A thin, greyish-white seam of rock runs diagonally down to the shore and disappears below the waves. It marks exactly the point at which two gigantic continents collided an unimaginably long time ago and it is the only place on Earth where what is known as the Iapetus Suture can be clearly seen. Between 480 and 430 million years ago, a vast prehistoric sea called the Iapetus Ocean was shrinking. It lay between three palaeocontinents – Laurentia, Baltica and Avalonia. The Earth’s crust was still young, forming and reforming vast landmasses. The immensely powerful phenomenon of tectonic shift was moving Laurentia, Baltica and Avalonia ever closer together and the Iapetus Ocean was narrowing. This remote episode of geological drama would determine the shape and nature of Borders landscape and throw up the hills that shelter Hawick.

On the southern edge of Laurentia lay the land that would become Scotland and on the northern shore of Avalonia was much of what would become England and Wales. When the palaeocontinents finally collided, a process lasting many millennia, they squeezed up the Southern Uplands between them, and the angle of the collision laid down the fundamental shape of Borders geography. Broadly, the ranges of hills and the course of rivers and their valleys run south-west to north-east precisely because of the way in which Laurentia and Avalonia were pushed into each other.

Differences in the nature of rock had the second determinant effect. When the much harder rocks of Scotland/Laurentia ground into England/Avalonia, scraping and crumpling together like an extremely slow-motion collision, they buckled and twisted the softer southern formations. The tremendous energy of the tectonic shift pushed up seams of coal and iron ore much nearer to the surface and, many millions of years later, the heavy industries of West Cumbria and Tyneside would be founded on this geological quirk. And, while the Industrial Revolution rumbled into life and mines were sunk into the softer seams to the south, the hard rock of the north would underpin some of the most fertile agricultural areas of Scotland.

Laurentia, Baltica and Avalonia formed part of Pangea, the massive single landmass that existed for millions of years surrounded by a vast ocean. It fragmented but, joined by the Iapetus Suture, Scotland and England stuck together. And geology influenced politics directly and the compass direction of the border between the two nations runs from the north-east to the south-west along the Cheviot watershed because of an ancient collision. That the collision at Flodden happened where it did is an accident of geology as much as history. And, when the hills and valleys of the Borders rose up out of the waters of the Iapetus Ocean more than 400 million years ago, that little known episode of tectonic drama merely served to underpin something that Borderers have always known – that our landscape and people are unique, not a part of Scotland or England but independent of either.

Around 350 million years ago, the tranquil plains of Pangea shuddered and suddenly erupted as a series of events of astonishing violence began. From the mouths of volcanoes, huge tonnages of ash, dust and pumice rocketed into the atmosphere, great storms blew, thunder boomed and rivers of white-hot lava flowed. Cheviot may be the stump of a gigantic volcano and the Eildon Hills the north-western rim of another but surely the most perfect relic of several eras of volcanic violence is the conical shape of Ruberslaw.

All of these hills are but a shadow of what they once were. Aeons of erosion have diminished them and, around a million years ago, the fire and thunder that spewed from their summits was stilled by the first of many ice ages. The most recent ended only 13,000 years ago – a mere blink of the eye in geological time. In places, ice-sheets more than a kilometre thick crushed what would become Scotland and the pitiless white landscape was dominated by vast, spherical ice-domes. One of these formed over Ben Lomond and, around its foot, cycles of low pressure brought near-constant hurricane-force winds, their velocity increased by the smoothness of the ice. Above them, on the summits of the ice-domes, high pressure produced endless days of dazzling sunshine. But it warmed nothing. At the height of the last ice age, around 16,000 BC, no plant, no insect, no animal, no human being could live in what was a desert of devastating beauty. And, under this thick and sterile blanket, Scotland slept, waiting to form, waiting for its green grasses, flowers and trees, its animals and, ultimately, its people.

When the thaw at last came, around 11,000 BC, it was dynamic. As the ice-domes began to splinter and crack and glaciers ground slowly down from their summits, they began to shape Scotland’s landscape. Singular and famous features like Stirling and Edinburgh castle rocks show the direction in which the melting ice moved. The tails of land on the eastern sides of both rocks (where people eventually began to build houses) and the sheer cliffs on the west are incontrovertible proof that the glaciers moved eastwards down the slopes of the Lomond ice-dome.

The same effects influenced the Borders landscape profoundly. As the ice scarted and ground its way eastwards, it carried along much debris. Locked into the mighty glaciers were huge boulders, pods of gravel and much else. Like prehistoric sandpaper, they scoured out the river valleys of the Borders, directing them eastwards to the North Sea. And fertile Berwickshire, eastern Roxburghshire and north Northumberland were where the ingredients that made the best soil on the flatter land were bulldozed and dumped. And, in western Roxburghshire, the ice broke out the watercourses that would become the Slitrig and the Teviot.

Scientists now believe that the ice retreated quickly – perhaps over the course of only a handful of generations. As the land warmed and summers lengthened, a green carpet of vegetation crept northwards. On what had been polar tundra, grass began to grow and, in sheltered places, willow scrub, birch and alder seeded and slowly spread. Watered by spring rains, pasture colonised the Tweed and Teviot valleys and herds of grazing animals followed it northwards. Wild horses, reindeer, elk and bison roamed the open spaces, always alert for predators. Cave lions, lynx and wolf packs circled the herds, searching out old, young or weak stragglers.

Behind the seasonal migrations of the great herds came their most deadly predator – human beings. Soon after the ice finally retreated, pioneers came north and traces of a very early encampment have been found at Cramond, near Edinburgh. It dates between 9,000 BC and 8,500 BC but all that excavators could scrape at carefully with their trowels were the remains of waste pits, soil discolourations where fires had been lit, some hazelnuts shells (organic matter crucial for radiocarbon dating) and stake-holes that once supported shelters.

Much more substantial was a remarkable find near the farm of East Barns. To the east of Dunbar, not far from the A1, archaeologists came across a circle of massive postholes, each large enough to accommodate a trimmed tree trunk. The angle at which the holes had been dug indicated that the trunks had been canted inward to form a conical structure, perhaps lashed together at the top or simply locked in place by its own weight. This was no mere shelter but a substantial and sophisticated house – and it dated to 8,000 BC. The construction implied all sorts of revisions. The pioneers who came north after the ice were hunter-gatherers, people who harvested wild fruits, roots, fungi, nuts (like the hazelnuts at Cramond), hunted animals and fished. Virtually nomadic, they were thought to have flitted through the landscape, barely rustling the leaves, leaving little trace of their passing. But here at East Barns was a house, a huge investment in labour, large enough to sleep eight to ten people – a family band who will have regarded it as their own and also claimed ownership of the land around it.

Coastal sites like Cramond and East Barns were good places to live 10,000 years ago. The landward area provided natural resources such as wood, stone and bracken for roofing and insulation and fresh water as well as its bounty of flora and fauna. In winter, when the land was less productive, the sea could be fished and mussel and oyster beds harvested at low tide. Many of the earliest settlements in northern Britain are to be found near the sea.

Pioneers preferred seaside sites for another simple reason. They knew where they were and could travel quickly and easily between locations – by water. The ancient technology of coracle and curragh construction is still alive in southern Ireland and skilled men can put together a well-made craft from greenwood rods, cord and fabric (instead of expensive hide) in a morning. These boats were undoubtedly widely used in prehistory, although it must be said that their wholly organic and relatively flimsy nature has meant that no sign of them exists in the archaeological record. Two of the many advantages of curraghs (coracles are rounder and generally used on lakes while curraghs are more canoe-shaped) were that they were light and easily carried and that they needed very little depth of water to float.

As men sailed along the coasts of the Firth of Forth after 8,000 BC, their landward vista contrasted sharply with the open sea. It was green and almost impenetrable. Trees had begun to grow and, as the weather warmed, they reached high altitudes, much higher than in modern times. Willow, birch and alder had been first but then came mighty oaks and tall elms. By 6,000 BC, Scotland was covered by the wildwood, a temperate jungle where the only paths were made by animals, where the overhead canopy was dense and at ground level it was humid and very shaded. The prey animals of the grassland plains had been replaced by forest species, some of them very dangerous. Brown bears browsed the undergrowth, fished the streams and no doubt searched for wild honey. The bones of wild boar have been unearthed on the banks of the Tweed near Coldstream and those of the huge wild cattle known as aurochs found at Synton Moss between Hawick and Selkirk. They were herbivorous but almost six-foot tall at the shoulder and, with a lyre-shaped horn spread of more than three feet, viciously pointed, they were not to be disturbed. Less alarming, beavers dammed the streams of the wildwood in the Borders and the remains of a birch wood felled by them around 5,000 BC have been identified near Earlston.

Hawick is about as far from the sea as it is possible to be in Scotland. Nevertheless pioneer bands did penetrate far inland – and very early. Some time around 6,000 BC, men and women cleared part of the wildwood near Teviothead. Pollen cores drilled out of peaty, anaerobic soil revealed data indicating that trees were felled or burned back at that time. Hunters may have been creating clearings where woodland animals could graze and drink and present themselves as easier prey.

These pioneers used rivers as their highways. It was easy to become lost in the dense and dark green of the wildwood and, if they came into the Borders from the east, up the wide mouth of the Tweed, their navigators will have quickly developed a mental map of the river system. Paddling where possible, picking up their curraghs on what they hoped were short portages, noting junctions with tributaries and recognisable geographical features near riverbanks, they will have penetrated far inland, perhaps at first on summer expeditions. Or perhaps the woodland clearers at Teviothead came from the west, by the Esk and the Ewes, before climbing the Mosspaul watershed.

Who were these people? Brave, resourceful and adventurous, they certainly came from the south. As the ice retreated and what became Scotland warmed, all of the first new arrivals came from the south – but from where exactly? That is not an impossible question to ask about people who lived 8,000 years ago. Borderers carry the answer in their bodies.

Far to the south, during the long millennia when the hurricanes whistled around the foot of the ice-domes over Scotland, human beings were sheltering from the cold and bitter weather. In the deep river valleys of the south-west of France, towards the Pyrenees, a series of extraordinary caves have been discovered. Inside them, in what are known as the Ice Age Refuges, men, women and children lived and survived. At those latitudes, the summers were long enough to see grass grow on the plains and forests flourish in the sheltered valleys. Like the later hunter-gatherers of the north, the people of the Refuges gathered a wild harvest and hunted game. But, unlike the pioneers, they left a remarkable, stunning record of their lives.

Famously at Lascaux, in the steep-sided valley of the River Vézère, a tributary of the Dordogne, they painted on the walls of their caves. Some time around 15,000 BC, when a sterile Scotland froze in the grip of the ice, these people painted animals and occasionally themselves. At the entrance to the cave at Lascaux is a monumental representation of four huge aurochs bulls. Herds of wild horses, deer and bison thunder across the walls of the cave and, in all, more than 2,000 paintings were discovered. And they are not unique. On either side of the Pyrenees, 350 painted caves have been discovered and they date from between 30,000 BC to 8,000 BC.

They were painted by our direct ancestors. DNA testing has shown clear genetic links between the people of the Refuges and modern Scots. One of the most ancient Y chromosome lineages detected amongst Scottish men is known as M284 and it came from the cave painters. After 12,000 BC, when the ice began to retreat, bands of men and women began to leave the Refuges and travel north, probably following the herds of wild horses, deer and bison. Some of them walked into Britain. At that time, it was not an island but linked to continental Europe by a vast landmass. And their descendants kept moving north, ultimately bringing their genes, M284, to Scotland. About 6% of all Scottish men carry this living link to the Refuges, approximately 150,000 Scots. And it may well be that a proportion of Borderers and men living now in Hawick carry it. Perhaps the woodland clearers at Teviothead first brought the marker to Scotland where it has remained and flourished.

Prehistoric artefacts found around Hawick are not especially informative. Perhaps one of the earliest objects in the Hawick Museum and Gallery at Wilton Lodge Park is a stone hand axe (that is, an axe without a handle) lifted out of the Teviot. Fashioned from greywacke, a hard local stone, it was used for everyday functions such as chopping wood. Its edges will have been blunted by many centuries of clashing against the stones of the riverbed but greywacke is a coarse sandstone and, unlike flint or chert, cannot be sharpened to give razor-like blades. Arrowheads made from flint have been turned up by the plough in fields around the town and, in Wilton Lodge, there is a mysterious stone ball. It appears not to have been functional but symbolic or religious in some unknowable way. What these and a handful of other objects can tell us about prehistoric Hawick is meagre – a grey rickle of stones and bones.

What the cave paintings made by the ancestors of the pioneers who came to Scotland after the ice can say, by contrast, is vivid and striking. Human beings advanced northwards very quickly and will have reached the Tweed and Teviot valleys within only a few generations, while the memories and traditions of the paintings were still fresh. In essence, these people were pre-eminent amongst our ancestors, the earliest arrivals.

Perhaps the first and most obvious observation about the cave art of southern France and northern Spain is how technically brilliant it is. Working in darkness lit only by guttering torches, the painters gave life to the giant aurochs, the horses, the lions and the deer. Their mastery of form and colour far exceeded that of much of medieval European art and the lifelike animals gallop and leap across the rock walls, their movement often fully understood and realised. The techniques of perspective were not fully grasped until the Italian Renaissance of the 15th century and yet the cave painters had developed simple devices to give depth to their creations. Artistic intelligence of the highest level was at work in the damp and darkness of these underground galleries and the notion that prehistoric people were somehow primitive and deficient simply fades into the background, where it belongs. When Pablo Picasso visited Lascaux soon after the end of the Second World War, he was astonished by what he saw, remarking, ‘We have learned nothing in 12,000 years.’

One of the most arresting images found in the caves is not that of an animal. As a form of signature, some prehistoric masters left a kind of stencil on the walls. Having filled their mouths with paint, they placed one of their hands flat on the rock surface and sprayed around it. It is a moving, direct link with a long past, our past. And it is also a long echo. When the great Italian painter, Raphael, was commissioned, patrons sometimes specified that the work should be done con il suo mano, ‘with his own hand’.

Our ancestors also believed, as we do, that art was magical and sometimes best experienced alone. When archaeologists found the hidden entrance to the painted caves at Chauvet in southern France in 1994, they knew that they were the first to see them for 27,000 years. And they also discovered who had been the last to see the lost art of a disappeared culture.