Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

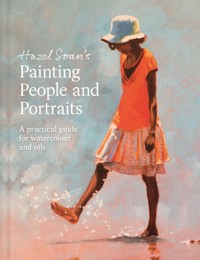

Master painting lively figures and private portraits, with simple exercises and step-by-step demonstrations. Bestselling artist and author Hazel Soan explains how to create beautiful and engaging paintings of strangers and loved ones, with handy hints and work-in-progress paintings throughout. Learn how to overcome shyness or anxiety about painting people in private and in public. Capture their energy and see beyond their likeness through angles, movement, tone and detail. Understand how to make them comfortable with poses, a timeframe and support. Learn about clothing, proportion, measuring and scene-setting. This is the only book you need for painting people and portraits. This extensive guide is ideal for all painters, new or experienced.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 120

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Coming Out of the Shadows

Watercolour, 56 × 76cm (22 × 30in)

To the Well, Uphill

Oil on Canvas, 20 × 20cm (8 × 8in)

Contents

Introduction

CHAPTER 1: Relationships: Seeing Like a Painting

CHAPTER 2: Practising People

CHAPTER 3: Pose and Proportion

CHAPTER 4: Perspective

CHAPTER 5: The Effects of Light and Shade

CHAPTER 6: Let’s Talk Composition

CHAPTER 7: Up-close and Personal: Portraits

CHAPTER 8: Clothing and Fabric

Conclusion: Expression and Narrative

Index

Acknowledgements

Game of Phones, Degrees of Separation (diptych)

Oil on Canvas, 180 × 60cm (71 ×24in)

To family, friends and fellow painters, many of whom are pictured here.

Game of Phones, Degrees of Separation (diptych)

Oil on Canvas, 180 × 60cm (71 ×24in)

Introduction

Painting people is fun, challenging and worthwhile. In this book you will find everything you need to paint people and their portraits with confidence and flair. The subject resonates with all of us – it is familiar, yet always new, allowing a natural and proper fascination with contours, lines, shapes, tones and colours explored through friends, family and strangers. Our associations with people imbue paintings with meaning by default, and although painting people can be daunting, this justifiably popular subject will thrill you once you get involved.

Heading in the Right Direction

Oil on canvas, 1 × 1m (2.2 × 3.3ft)

I enjoy painting many subjects, but people weave meaning into the painting process. Even when figures are anonymous, I become attached to each one, ‘recognizing’ individuals in the figures that emerge.

Shadows in Leicester Square

Oil on board, 23 × 30.5cm (9 × 12in)

I am constantly attracted to the patterns that crowds of people make as they walk to and fro through light and shadow, especially in urban settings.

Familiarity Breeds ...

Familiarity ought to make painting people worry-free but conversely the inclusion of figures and faces in paintings often attracts extra anxiety, probably stemming from the heightened judgment that this subject seems to attract. Maybe we are touchy about misrepresentation, but figures in a painting automatically draw our attention and they can draw our criticism too. It seems they cannot be ignored! This challenge can make painting people scarier than other subjects, causing hesitation or even avoidance, and thus denying yourself a lot of fun and satisfaction. This book aims to dispel the fear, and give you confidence to paint people and their portraits in any setting! Since I paint in both watercolour and oil, differences in approach and technique will be highlighted where appropriate. Within most chapters, there are Go Paint! pages with suggestions to practice and get you off to a good start.

Riverside Verona

Watercolour, 33 × 24cm (13 × 9.5 in)

The landscape was painted first, but as soon as the people were added in the bottom left-hand corner, the bridge, which was previously the subject of the painting, became the background and the figures become the subject.

We Are the Story

Unless the figures in a composition are really insignificant, as soon as you include people in a painting, the painting instantly becomes about their narrative. Bring figures into a beach scene, for example, and the viewer’s eye will fall upon the bathers before exploring the sand and the sea. Add to this an active pose and the figures will draw even more attention. It is no wonder, then, that painting people causes angst – once you decide to include them in your paintings, or make them your main subject, you risk being judged by whether they succeed in justifying their presence. Perhaps this raised level of accountability is because representing our own species is the most significant subject an artist can paint? If so, that explains why it can be daunting, and also the most fulfilling.

Market Day

Watercolour, 28 × 28cm (11 × 11in)

Little is needed to suggest a narrative. Even without any background setting and the anonymity of a back view, this figure tells a story that is evocative.

It’s All About Relationships

As you read this book and explore the engaging subject of painting people and portraits, you will notice that painting people is about relationships: the relationship between the artist and their subject, the relationships set up on the two-dimensional surface of the canvas or paper, and the relationship between the painting and the viewer.

Within these pages, you will learn how to paint lively figures, how to include figures in wider settings, how to paint individuals, and come in close for a portrait. However, you will be constantly reminded (by me!) that in each scenario the image created is a painting. Paintings are not people, but flat patterns of colourful shapes and tones presented on a two-dimensional surface. Figurative paintings represent the three-dimensionality of the real world: they can be entertaining, interesting and appealing, and they also have the mysterious power to move people, even to tears. It is because they carry meaning that making paintings of people is worthwhile. It can be scary, but the challenge is within your grasp.

Maasai Chief

Watercolour, detail

A portrait is born when a pattern of light and shade in a variety of tonal values comes together on the paper to describe a face. This Maasai chief had never seen paintings and our guide, his nephew, described it to him as writing. When shown the image, he recognized his white hair and was satisfied.

Corridor of Light

Watercolour, 61 × 43cm (24 × 17in)

I made this painting because the relationship between the shapes of light and shadow excited my eye and I wanted to share the thrill. The figures remain anonymous, their movement described simply by colourful shapes, their narrative expanded by the intervals between them to create a wordless and (hopefully) intriguing tale.

Seeing Patterns

To make effective figurative paintings, the first relationship to attend to is that between the artist and the subject. When you want to paint somebody, or a group of people, or even place figures in a landscape, you should ask yourself what it is that excites or interests you about them. Why do you want to paint them or add them to the painting? The answer will help steer your concentration, allow you to leave out what does not interest you, and so paint and place them effectively. For example, if you are painting someone you know, you will probably want to please the sitter, working quickly in case they tire, and wanting to achieve likeness. But if the person is anonymous, say a stranger on a train, likeness may not be as important, and the concentration might be on the pose rather than the face.

The next relationship is between the elements that make up the physical painting. In order to make a painting work, shape, line, tone and colour have to come together to form a composition. This requires balancing the relationships between the shapes, spaces and intervals on the canvas or paper. These relationships could be within the figure, between figures, or within the features of a face, and these have to be translated into shapes and lines on a two-dimensional surface. Think of what the painting needs in order to succeed. To ‘see’ as a painting ‘sees’ requires seeing the subject as a two-dimensional pattern. The three-dimensional form or space you suggest is an illusion created by light and shade and perspective.

Weekend in Venice

Indian ink, 51 × 51cm (20 × 20in)

The shape of the gap between the two people leaning on the bridge is as important to the two-dimensional plane as the shapes of the actual figures. The interval allows the painting to hint at the relationship between the two people.

Umbrella Company

Oil on canvas, 51 × 51cm (20 × 20in)

A striking pattern is created on the flat canvas by the arrangement of the figures, the umbrellas and the spaces between them. These are balanced across the picture plane and endorsed by a counterchange of coloured tones.

A Shared Relationship

The third relationship only comes into play when the painting is finished and is the interpretative or emotional one forged between the painting and the viewer in response to the figures or persons portrayed. This relationship cannot be engineered but it can be manipulated, and differs depending on the audience. Like the other arts, such as music, theatre and literature, painting is entertainment. Whereas music is entertainment for the ears, painting is entertainment for the eyes. If a painting successfully entertains the eye, it will resonate with its audience and may be granted access to the soul.

Maasai Herders

Watercolour, 30.5 × 66cm (12 × 26in)

Moved by both the camaraderie and the slender agility of the Maasai herders, I made this painting across the spread of my sketchbook, aware I was also trying to convey my respect and admiration.

Making it Happen

As already mentioned, since paintings are two-dimensional, the painter’s main task is to make the relationships between the painterly elements on the flat surface of the paper or canvas come together in a workable whole. This is achieved by balancing the lines, shapes, values and colours. The aim is to ensure the lines have purpose, the shapes are actively descriptive, the patterns exciting, the tones convincing and agreeable, and the colours captivating. To the flat surface of a painting, people are no different from plants, boats, pots or rocks. It is the art (and privilege) of the painter to turn a pattern of painted blobs into the illusion of a person or their face, bringing all the elements of painting together in a way that appeals to the eye and moves the mind, heart and soul of the viewer.

The Speed of Life

Oil on canvas, 30.5 × 43cm (12 × 17in)

This painting is a pattern of black and blue shapes separated by bands of pale yellow. By making descriptive shapes they can be read as people hurrying home while shadows lengthen at the end of a working day.

Paint Life From Life

We may think we are familiar with the shapes and poses people make, but we never truly know what something looks like until we attempt to draw or paint it. I would love to promise that this book can teach you how to paint people by osmosis, but no matter how many times you read this book, it can only help you if you actually paint! Familiarity with the subject is the starting point. Practice painting people from life and you will become familiar with the shapes and poses they commonly make.

If you can get out, take a trip to your local high street or mall, train station, bus stop, promenade or beach – anywhere that people gather. Fill the pages of a sketchbook with multiple quick figure sketches of passers-by. Not only is this a fast way to grasp proportion and pose, but it is also great fun! The next few pages will suggest an approach and give ideas.

It takes surprisingly little to represent a figure on paper: an oval blob denotes a head, an elongated rectangle the torso, two sticky-out bars for the arms and two drop-down bars for the legs.

A Seat With a View

Ideally, sit yourself down somewhere with a longish view so that the people are far from you, but not too small to see to paint, and mostly standing around or walking towards or away from you, rather than back and forth across your line of vision. The figure sketches I make are small, about 5–8cm (2–3in) high, and painted with watercolour directly onto the paper because the brush can immediately demarcate shapes but drawing an outline takes longer.

If painting from life is not an option, flip though magazines or books to find pictures of people in natural everyday poses – out shopping, at sports events, standing in groups and in lines. Imagine they are moving so that you keep the sketches rapid and uncomplicated.

We have no trouble accepting that a few blobs and lines can represent figures.

I take my sketchbook out into city streets and squares, filling the pages with figures in a variety of poses that I can later transfer into paintings.

Figure Shapes and Poses

When you start, choose people standing around as static poses give more time to garner proportion and grasp pose. When you feel comfortable with these, you can graduate to figures coming towards or walking away from you. This allows time to register the lift and fall of legs in movement.

As confidence grows, paint figures walking across your line of vision, looking out for the alternating triangular spaces between the knees and thighs as the knees cross back and forth. These sketches will take seconds, not minutes, so bring plenty of paper!

Start in monochrome with standing figures, letting your brush dance lightly on the paper. Resist the temptation to tamper with the shapes. The natural irregularity inherent in a brushstroke makes a livelier figure than if you try to satisfy or correct the pose.

Once you feel you are getting the hang of the proportions, move onto active poses. Use slightly drier paint and dash the brushstroke across the paper to allow it to break up and create a ragged edge. This fragmentation infers movement in the pose.

As you become confident with individual figures, look for pairs and groups, linking figures together in one blended shape. Small gaps between the limbs add interest to a pose.

Rain in St Mark’s Square I

Watercolour, 30.5 × 30.5cm (12 × 12in)

The lively silhouettes that represent the groups of figures hurrying through the rain can barely be said to describe human shapes and yet we have no trouble reading them as people in the square.