6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

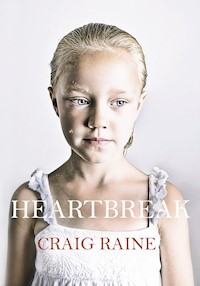

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

What becomes of the broken-hearted? Craig Raine's first novel is an exquisite, moving, erotic investigation of love and its painful corollary. In Heartbreak, Craig Raine's startlingly moving, intellectually nimble, sexually candid, wickedly funny first novel, the central character is not a person, but an invisible metaphor: heartbreak. Through the stories of a virtuoso cast of characters - among them a physically scarred academic, a strangely beautiful young girl with Down's syndrome, a world-renowned actress, and a brilliant Czech poet - Heartbreak investigates one of the most elusive yet deeply felt of human conditions. It is a compassionate and textured novel about what happens to us when love and loss collide.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

HEARTBREAK

Also by Craig Raine:

The Onion, Memory A Martian Sends a Postcard Home Rich History: The Home Movie Clay. Whereabouts Unknown A la recherche du temps perdu Haydn and the Valve Trumpet In Defence of T. S. Eliot T. S. Eliot Collected Poems, 1978–1999 ‘1953’

First published in Great Britain in 2010 in hardback by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Craig Raine, 2010

The moral right of Craig Raine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

The extracts from ‘Stop all the Clocks’ and ‘Anthem for St. Cecilia’s Day’,Collected Poems, W. H. Auden (Faber and Faber, London, 2004) © The Estate of W. H. Auden and reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

The extract taken from ‘Little Gidding’, Complete Poems and Plays, T. S. Eliot (Faber and Faber, London, 2004) © The Estate of T. S. Eliot and reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

‘I Wish I Were In Love Again’. Words by Lorenz Hart, Music by Richard Rodgers © 1937 (Renewed) Chappell & Co., Inc. (ASCAP)

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84887 510 4 ePub ISBN: 978 1 84887 999 7 Mobi ISBN: 978 1 84887 999 7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my son Moses,

who gave me the idea for this book and one of its best jokes

‘The man in the brown macintosh loves a lady who is dead’

– James Joyce, Ulysses

Contents

Stop All the Clocks

PART I: A Passion For Gardening

Damp Squib Followed by Fireworks

PART II: Gallagher and Frazer

I Was So Unfair

Miroslav Holub

PART III: Annunciata Williams-McCrae

By Design

PART IV: Heart Failure

Enobarbus

All That Flesh and Blood

PART V: Desert Island Discs

As the Actress Said to the Bishop

Many Happy Returns

Fashion Statement

You Don’t Understand

Breakfast at the Bishops’

Kristin Scott Thomas at the Royal Court

Her Greatest Role

And Then He Kissed Me

RADA

The End of the Affair

Desert Island Discs

PART VI: All I Want is Loving You – and Music, Music, Music

Hans von Bülow

A Conductor’s Perquisites

Cosima von Bülow

My Mother and Henry James

Reluctant Richard Wagner

Nymphenburg, München, the Villa von Bülow

Force the Moment to Its Crisis

The Children

Tribschen, Lake Lucerne

A Footnote about Ann Golding

PART VII: Find the Lady

Princeton

First Kiss

How the Thought of You Lingers

The Male Gaze

Strike the Father Dead

Fucking Assia

PART VIII: Without Acknowledgement

In Flagrante

I Want a Divorce

The Sexual Imagination is Transgressive

The Royal Festival Hall

She Knew He Knew

Mrs Kipling’s Heartbreak

PART IX: Work Experience

Olly

PART X: CODA

Acknowledgements

Stop All the Clocks

Miss Havisham has had her heart broken. She has been jilted at the altar itself. In Great Expectations, Dickens gives us standard-issue, instantly recognisable, consensual heartbreak but in a dramatically lit version. She is still in her trousseau, her veil a cobweb, presiding over the ruins of her wedding reception. The cake is like an opera house after an earthquake. There is a Beckettian drama of dust thick over everything. Like the three principals in Play, Miss Havisham is trapped in a constricted vicious circle of repetition. Because her heart is broken, nothing now works, not time itself. We enter an oubliette that remembers only one event. Dickens doesn’t tell us Miss Havisham’s Christian name. It could be Trauma. Or Aporia. All the clocks are stopped at twenty minutes to nine, the very moment when her heart was broken.

‘Stop all the clocks’, Auden’s cabaret song, is about the failure of love – about heartbreak. It isn’t about the death of a lover, as readers commonly assume – including Richard Curtis, the script-writer of Four Weddings and a Funeral. Auden’s song (written for Hedli Anderson) is too hyperbolically comic to be seriously elegiac: ‘Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone’; ‘Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves’; and (the source of the mistake) ‘Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead / Scribbling on the sky the message He Is Dead …’ But only in a manner of speaking.

What do we learn from these shared clocks? The full implication of ‘broken’. That things no longer work and, oddly enough, that repair is out of the question. There is something odd, something impossible, about the words ‘broken’ and ‘heart’ put together. You can’t break a heart. It isn’t a mechanism, in this instance. It is a figure for love. When the heart’s mechanism breaks down, we call it heart failure. It is a physical condition. So what do we make of this impossibility – heartbreak?

We learn that heartbreak is hyperbolic – an exaggerated claim to an impossible condition. Those who claim it make exaggerated claims for it. You can hear them raising their voices – so they can shout down the idea of recovery. So others will know what they are suffering. Misery is being acted out.

Finality is being acted out.

But what about the ones who aren’t shouting? Who aren’t acting the role like Miss Havisham?

People more like Catherine Sloper in Washington Square. People whose hearts are invisible.

What is heartbreak, really?

Is it really only rhetoric?

PART I

A Passion for Gardening

Damp Squib Followed by Fireworks

It was 5.30 in the grey morning. Carmen Frazer, who slept lightly, was already dressed. With thickening fingers, she pinched the yellowing leaves from the bottom of the chilli plant on her kitchen windowsill. The plain white saucer had two tartar tidemarks of lime scale and a mascara of grit in the remaining dirty water. Her passion was gardening.

She was 66 and had been retired for seven years. Her sturdy rubber-tipped cherrywood walking stick leaned in the corner. Arthritis of her left hip had made her job at Oxfam impossible: she was co-deputy editor of JobsWorth, a small in-house magazine. But the stairs were too difficult. Manoeuvring herself into the car wasn’t easy either. She was in constant pain, despite the anti-inflammatories. Toothache the length of her leg, touching a nerve. For her valete in JobsWorth, she made a little joke: who put the ‘ouch!’ in touch? (Colleagues at Oxfam had always found her ready, nervous laugh irritating. Anything – the weather, mention of a queue at the post office – could activate that bright, brief, unconvinced laughter, a door-chime of high soprano, a joke alarm at the lowest setting.)

A second rubber-tipped beechwood outdoor walking stick stood in the hall. Her walk had a dramatic list to the right as she took the weight off her stiff left leg. To spectators, it looked as if the trouble were in the right leg. As if it were shorter by six inches. Wrong. The hitch was like some South American dance step – a secret weight change in the tango. Except that it wasn’t secret. Only misleading.

In 1964 she had taken a boat to Valparaiso. It flew the Liberian flag – easily mistaken for the Stars and Stripes – but was called the Regina del Mare and was crewed by Italians mainly, with four Russians who smoked together in the evening – cigarettes with pinched cardboard tubes. It sailed from Liverpool. She was 22. She was going to marry Frank, her fiancé. It was the first and, as it proved, the only time she ever went abroad. The fare, one-way, round Cape Horn, was £275 and fifteen shillings. It included two meals a day. The journey by sea took ten weeks. In that time, she spoke only five words of English: yes, no, please, thank you. Her laugh, she found, was multilingual, a kind of Esperanto. She became familiar with the horizon. She read and then re-read the ten Agatha Christies in her travelling trunk.

When the ship anchored in Montevideo, to provision and take on fuel, at night she heard for the first time the stridulation of insects like an automatic sprinkler system. In the morning, when she walked to the consulate, carefully watching her sandals on the pavement, she glanced up and saw a Negro wearing a stack of panama hats. Maybe twelve. She never forgot the bandoneon of brims, the perfect stutter of hat. There was no mail waiting for her at the consulate.

On the way back, keeping to the shady side of the streets, she saw the bronze scrotum in a bronze church bell. She waited a while, wanting it to strike, staring at the dark metal bruise where it had struck before. Where it always struck. When it struck. But not today, a Saturday.

At the docks, there was a large white ocean-going yacht like a bride. A member of the crew, in white ducks, was leaning out, awkwardly swabbing the white sides with a chamois leather at the end of a long cleft stick – a ginkgo leaf of gold leaf.

How dark her cabin after the aching sunlight, as if she were about to faint. She turned her waistband, undid the zip, stepped out of her skirt and lay on the bunk in her slip. She was trying to think what the sway and the slight bounce of the gangway reminded her of. It came to her. It was like the ship – when it was calm.

At Valparaiso, there was no Frank. There was a messenger who spoke her name as she looked about her, shielding her eyes, her other hand on the green, brass-bound trunk. ‘Misshess Carmen Frasseur?’

‘Sí.’

He was wearing a double-breasted dark blue suit with sandals. His toenails were dirty. There was an oil stain on his left lapel. His features, though, were handsome. First he showed her a small snapshot of herself – lifting a glass of stout towards the person (Frank) taking the photograph. She was smiling, tensely. Then the messenger held up his left hand, paused, patted his jacket and produced from the inside pocket a letter curved by his ribcage. Then he turned and disappeared between the stacks of dockside crates. No name. The envelope was blank – except for a pastel smudge, franked by the messenger’s thumb, which she smelled. Coffee grounds.

Frank’s letter was written on lined paper, the top edge a ruffle where it had been torn from a spiral notebook. What it said – that he was sorry, that he had fallen in love with someone else in Chile, another English woman actually, and he had married her – was of no importance. There was no address. But she had his address in her passport and also in her purse. There was a telephone number. She decided not to ring it. Instead, she beckoned a Negro boy with a porter’s brass lozenge and paid him to carry her trunk back on to the boat.

The ship was a week in port before it began the return journey of eleven weeks. For some reason, the return journey took a week longer. She had money for the return fare with a goodish sum left over. She had been saving for a long time. In Valparaiso she never left the boat again. She had been on the dockside for ten minutes, including the time it took to read Frank’s letter.

On the voyage home, she was, she could tell, a figure of interest, of speculation. Of mystery, in fact. Mainly because she hadn’t cried or even looked upset.

She felt insulted and wounded and yet it was a relief.

On the last night in Valparaiso, there was a fireworks display, to celebrate the departure of the plague in 1572 which had claimed 150,000 lives in less than two years. She decided not to watch it. She had seen fireworks before and she wanted to think. The porthole of her cabin bloomed and flickered, tarnished and brightened, like the iris of someone watching fireworks. ‘Some bearded meteor, trailing light.’ She smiled. She smiled and listened to the bombardment overhead. It lasted thirty minutes and had a surprising dynamic range. The crump of grenades, all grades of ordnance, tracer, tormented shrieks, viciously beaten bass drums, glissandos. A great orchestra of violence, deprived of visual distraction.

She was thinking about the messenger – the way he put his dark glasses over those friendly, handsome eyes, the way he went between the crates, like a pigmy. Or like a giant in Manhattan.

And she came, with a definite jerk, for the first time in her life.

Sharp, then strangely long, like an injection.

Every evening at sea, to the music of Joe Loss on a portable gramophone, she watched two sisters from Slough, in their late thirties, efficiently dancing, breast to breast, on the tiny sloping dance floor. They both worked in the exchange department of Lloyds bank. They had identical wristwatches, equally high on their freckled forearms, and they were going to marry two twin sailors from Valparaiso when they returned in six months’ time. They took turns as leader and follower.

Here she is at her kitchen table, fingering a jigsaw of thalidomide ginger, thinking about the arthritis in her hands. Her knuckles like bunions, her deviant final finger joints. In the field, beyond the barbed-wire, there are four sheep in their tea cosies that she looks at but doesn’t see. She is remembering.

What puzzles her – and what puzzles me – is why she is still attached to a man with whom she was never happy. He hated her laugh and said so. He didn’t like the way she smiled. ‘Why do you smile like that? As if you’re scared.’ She held her knife incorrectly at table. They couldn’t even talk: ‘You interrupt me like your mother.’ Everything about her irritated him. Especially in bed. His large penis hurt her. It was a source of resentment (in him) and soreness (in her) that she never came. ‘You’re supposed to like a big cock.’ From the beginning, he found it difficult to come. ‘Look, it’s like dancing. Why can’t you dance?’ He was righteous and indefatigable. She suffered constantly from the itching, thrush, and other yeast infections.

No wonder Frank had fallen for someone else.

(Who was equally unhappy.)

And here she was, thinking about him, thinking about his eyes, thinking about the way he thought, the tell-tale compression of his lips, thinking thirty, forty years later, about their lost life together. It would have been misery, but it made no difference. She had given herself, her narrow hips that wouldn’t open wide enough at first, her mouth, her hands, the gold-beige, semiprecious hair on her vagina, the vagina itself.

And in return had been given this pendulous body in the big bathroom mirror, gorgonzola dolce, grotesque with gravity, concealed by condensation. In the fog, her upper torso swayed like a bloodhound, nose sampling a spoor.

Colin at the garden centre was recovering from cancer of the throat and vocal cords. A silk scarf hid the radical surgical intervention. It wasn’t a scar exactly. His neck had gathered round a raw hole, withered like a sick plant. And his voice had changed. It crackled and buzzed like a walkie-talkie.

They were discussing the ginkgo.