Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

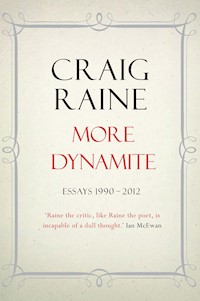

More Dynamite anthologizes a wealth of essays by a writer with one of the keenest critical eyes of his generation. Craig Raine - poet, critic, novelist, Oxford don and editor - turns his fearsome and unflinching gaze on subjects ranging from Kafka to Koons, Beckett to Babel. He waxes lyrical about Ron Mueck's hyperreal sculptures and reassesses the metafiction of David Foster Wallace. For Raine, no element of cultural output is insignificant, be it cinema, fiction, poetry or installation art. Finding solace in both literature and art alike, and finding moments of truth and beauty where others had stopped looking, More Dynamite will reinvigorate readers, challenge our perceptions of the classics and wonderfully affirm our love of good writing, new and old. This extensive collection of essays is a crash course in twentieth century artistic endeavour - nothing short of a master class in high culture from one of the most discerning minds in contemporary British letters.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1233

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MOREDYNAMITE

Also by Craig Raine

The Divine ComedyHow Snow FallsHeartbreakThe Onion, MemoryA Martian Sends a Postcard HomeRichHistory: The Home MovieClay: Whereabouts UnknownÀ la recherche du temps perduHaydn and the Valve TrumpetIn Defence of T. S. EliotT. S. Eliot: Image, Text and ContextCollected Poems, 1978–1999‘1953’The Electrification of the Soviet UnionA Free TranslationA Journey to GreeceChange

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Craig Raine, 2013

The moral right of Craig Raine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The author is grateful to the following publications in which the essays of this book originally appeared, sometimes in slightly different form: Areté, the Times Literary Supplement, the Kipling Journal, the Financial Times, Peter Lang, Penguin Books, the New Statesman, the Daily Telegraph, the Guardian, Another Magazine, the London Review of Books, Modern Painters and Memory: An Anthology.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 9781848872875E-book ISBN: 9781782392057

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWCIN 3Jz

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Patrick Marber and Debra Gillett

Contents

Part One: Books – Reading the Fine Print

Isaac Babel (2002)

Derek Walcott’s Poetry (2000)

Raymond Carver (2009)

Elizabeth Bishop (2008)

William Golding (2009)

William Golding’s The Spire (2011)

Updike: Just Looking (1990)

Updike Tribute (2009)

Memory in Literature (2005)

Kipling and Racism (1999)

Just So Stories (2001)

Stoppard’s Trilogy (2002)

Stoppard: A Speech (2004)

Life Studies (2003)

Robert Lowell’s Collected Poems (2004)

Lowell’s Letters (2005)

The Lowell–Bishop Letters (2008)

Double Exposures: Ted Hughes (2006)

Ted Hughes’s Letters (2007)

A. E. Housman’s Letters (2007)

Marianne Moore (2004)

V. S. Naipaul (2001)

J. M. Coetzee (2007)

Geoffrey Hill, Christopher Logue, Seamus Heaney (2005)

J. M. Coetzee’s Disgrace (2010)

Kundera’s Italics (2006)

Kundera’s The Curtain (2007)

Christopher Logue (2007)

Counter-Intuitive Larkin (2008)

Rebecca Gilman: Dramatist (2004)

Joyce’s Exiles (2006)

Harold Pinter Remembered (2009)

Short Bit about Beckett (2006)

Don Paterson (2007)

Kafka: The Trial (2001)

Laughter in the Dark: Nabokov (1998)

Paul Valéry’s Notebooks (2000)

Auden’s Early Poetry (2005)

Auden’s Prose (2008)

Zbigniew Herbert (2008)

Not about Heroes (2006)

Opera as a Flawed Form (2004)

Influences (2004)

Poetry and Language (2004)

Short Introduction to T. S. Eliot (2008)

The Laureate (2005)

Consider the Hipster: How Good is David Foster Wallace? (2011)

Eliot’s Inferno: The Letters (2009)

Bryan Forbes (2010)

Alan Bennett: The Angst in the Axminster (2009)

Salinger: ‘A Perfect Day for Bananafish’ (2010)

Sex: Mrs Whitehouse and Mrs Eagleton (2010)

Part Two: Art – Reading the Detail

Seurat’s Courage (1997)

Old Friends in Venice (1995)

Claes Oldenberg and Coosje van Bruggen (1999)

Masterpieces: Things in Particular (1997)

Frank Gehry (1998)

Ron Mueck (2000)

Mueck at Kanazawa (2008)

Mueck: Invitation au Voyage (2009)

Modigliani (2006)

Adam Elsheimer (2006)

Klimt (2008)

Richard van den Dool (2005)

Jeff Koons (2009)

Rodchenko (2008)

Sickert in Venice (2009)

Vorticists (2011)

Gerhard Richter (2011)

Hockney at the Royal Academy (2012)

Damien Hirst Retrospective (2012)

Acknowledgements

A Note on the Author

Index

PART ONE

Books – Reading the Fine Print

Isaac Babel

(2002)

My wife, Ann Pasternak Slater, met Nadezhda Mandelstam in Moscow in 1971, shortly after the publication of Hope Against Hope. The sequel, Hope Abandoned, was finished and waiting in another room. The poet’s chain-smoking widow jerked her thumb over her shoulder: ‘More dynamite in there.’

Isaac Babel was another dynamitist – a writer whose explosive force derives from his terse transcriptions of first-hand experience. He wrote to his friend Paustovsky: ‘on my shield is inscribed the device “authenticity”.’ Some paragraphs of his prose are acts of deliberate terror. The simple shock-waves of the actual, the cruel, the irrefutable, are his speciality. His sudden, ruthless, marvellous gift leaves the reader trying – too late – to look away from what Babel is compelled to show us. There is no escape. The violence is calculated to injure the reader’s bourgeois sensibility, to destroy his good taste, to trap him in the epicentre of the blast – to terrorise him.

Dulgushov is fatally wounded: ‘He was sitting propped up against a tree. He lay with his legs splayed far apart, his boots pointing in opposite directions. Without lowering his eyes from me, he carefully lifted his shirt. His stomach was torn open, his intestines spilling to his knees, and we could see his heart beating’ (my italics). The narrator lacks the ‘courage’ to finish him off, as the wounded man asks.

‘Afonka Bida’ tells the story of a Cossack whose wounded horse has to be shot. First, he feels in the wound with his copper-coloured fingers, then a comrade shoots the horse: ‘Maslak walked over to the horse, treading daintily on his fat legs, slid his revolver into its ear, and fired’ (my italics). Deranged with grief, Afonka Bida goes on the rampage and returns with a replacement mount. It has cost him an eye: ‘he had combed his sweat-drenched forelock over his gouged-out eye.’

Afonka expresses his sorrow in a phrase – ‘Where’s one to find another horse like that?’ – which recalls another story in the collection, ‘Crossing the River Zbrucz’. The narrator is billeted on a family of Volhynian Jews in Novograd. He lies back on ‘the ripped eiderdown’ and dreams restlessly about battle. He is woken by a pregnant Jewish woman tapping him on his face. I quote the rest of the two-page story, about one quarter of the total:

‘Pan,’ she says to me, ‘you are shouting in your sleep, and tossing and turning. I’ll put your bed in another corner, because you are kicking my papa.’

She raises her thin legs and round belly from the floor and pulls the blanket off the sleeping man. An old man is lying there on his back, dead. His gullet has been ripped out, his face hacked in two, and dark blood is clinging to his beard like a lump of lead.

‘Pan,’ the Jewess says, shaking out the eiderdown, ‘the Poles were hacking him to death and he kept begging them, “Kill me in the backyard so my daughter won’t see me die!” But they wouldn’t inconvenience themselves. He died in this room, thinking of me ... And now I want you to tell me,’ the woman suddenly said with terrible force, ‘I want you to tell me where one could find another father like my father in all the world!’

That sudden ‘terrible force’ is Babel’s speciality, too. But it depends not just on the way the mundane nightmare is succeeded by the infinitely worse waking nightmare. It depends also on what follows the dark blood in the beard – shaking out the eiderdown. In those four alert words is all the shock, all the tragic incongruity, of ordinary life’s unbearable, bearable continuities.

This is ‘Berestechko’ and more Jews:

The old man was screeching, and tried to break free. Kudrya from the machine gun detachment grabbed his head and held it wedged under his arm. The Jew fell silent and spread his legs. Kudrya pulled out his dagger with his right hand and carefully slit the old man’s throat without spattering himself. He knocked on one of the closed windows.

‘If anyone’s interested,’ he said, ‘they can come get him. It’s no problem.’ (my italics)

You know it is true. No fiction writer would dare this black farce – the fastidiousness of the barbarian’s meticulous barbarity, the etiquette observed by the executioner knocking on the closed window. It is writing with the greatest possible specific gravity. It exerts an awful, irresistible pull on the reader. There are the ingredients for a sick joke here, the shape of perverse laughter – but Babel skirts the absurd and renders it as sober, almost off-hand, factual, unquestionable.

The casual cruelty and the laconic prose recall the italicised prefatory micro-bulletins above the stories in Hemingway’s In Our Time. Quoted like this, the Babel stories satisfy the imperatives set down in his diary: ‘short chapters saturated with content’; ‘very simple, a factual account, no superfluous description’; ‘rest. New men. Night in the field. The horses, I tie myself to the stirrup. – Night, corn on the cob, nurse. Dawn. Without a plot.’

Of course, there are moments of more insidious vividness – a prostitute squinting to squeeze a pimple on her shoulder, a Jew on his way to synagogue (‘he fastened the three bone buttons of his green coat. He dusted himself with the cockerel feathers’), ‘a moaning hurrah, shredded by the wind’. Babel knows the ‘round shoulders’ of plump women. He is as expert on backs as a chiropractor: ‘scars shimmered on her powdered back’; passion means that ‘blotches flared up on her arms and shoulders’; ‘her back, dazzling and sad, moved in front of me.’ Or there is the mistress of Division Commander Savitsky, ‘combing her hair in the coolness under the awning’, smilingly chiding her lover as she buttons up his shirt for him. Not unbuttoning, but the far greater intimacy of buttoning up.

This is an utterly authentic vignette of a landscape transformed by battle:

Cossacks went from yard to yard collecting rags and eating unripe plums. The moment we arrived, Akinfiev curled up on the hay and fell asleep, and I took a blanket from his cart and went to look for some shade to lie down in. But the fields on both sides of the road were covered with excrement. A bearded muzhik in copper-rimmed spectacles and a Tyrolean hat was sitting by the wayside reading a newspaper.

The fatigue we might have guessed – and even the excrement – but it took Babel’s being there to assure us so confidently of those unripe plums and that implausible yet irrefutable Tyrolean hat. Equally, Babel’s first-hand knowledge can assure us that cooking pots are stirred with a twig, or that sleeping cavalry tie their horses to their legs. Or consider the narrative hypnosis that holds us while a Cossack, Prishchepa, executes a bloody revenge to restore the looted furniture to his family hut. He arranges it as he remembers from childhood, drinks vodka for two days, sings, cries – and finally sets fire to the hut. Before he vanishes, he throws ‘a lock of his hair into the flames’. A remarkable, inexplicable, unforgettable final touch.

Elsewhere, Vytagaichenko, the regiment commander, is woken by a Polish attack. ‘He mounted his horse and rode over to the lead squadron. His face was creased with red stripes from his uncomfortable sleep, and his pockets were filled with plums.’ The creases are good, but they are to be expected. The plums are the surprise – the authenticating detail, the guarantee of genuineness, by this alert connoisseur, this calm Berenson of the battlefield. Both Lionel Trilling and Henry Gifford are exercised by the perceived conflict between the timorous intellectual and the warriors he fought alongside. (See Trilling’s introduction to Collected Stories (Methuen, 1957) and Gifford’s shrewd and learned essay in Grand Street (Autumn, 1989).) In a revisionist spirit, Gifford offers the testimony of Viktor Shklovsky, the Russian formalist, who knew one of Babel’s comradesin-arms: ‘They liked Babel very much in the army. He had a calm fearlessness of which he was quite unconscious.’ The internal evidence of the stories suggests how closely this was related to an almost scholarly impulse. Those plums are recorded twice in the unflinching spirit of thoroughness – the pedantry of genius.

But selective quotation is distorting. It ignores the aesthetic pleasure of form and shapeliness. The stories are wholes. Who can tell from fragmentary quotation whether that verbal parallel lamenting the loss of a father and the loss of a horse is intentional and ironic, or inadvertent repetition? (There are unintentional repetitions in Babel, but here I think he is covertly ironising horse-centred Cossack morality.) A weak, early, overwritten, knowingly improbable story like ‘Shabos-Nakhamu’ can look intriguing if you quote only the last paragraph: ‘The innkeeper, naked beneath the rays of the rising sun, stood waiting for her huddled against the tree. He felt cold. He was shifting from one foot to another.’ And, up to now, most of my quotation has been sensationalist and Babel’s subtler registers under-represented. For example, ‘Dolgushov’s Death’ is more than its core – the slow cascade of intestines and flexing heart of Dolgushov, who is eventually put out of his misery by Afonka Bida. He shoots the dying man in the mouth. Bida despises the bespectacled, ineffectual narrator, whose fastidious tenderness is actually a form of cruelty – and he threatens to shoot him, too. The story ends like this: ‘“Well, there you have it, Grishchuk,” I said to him. “Today I lost Afonka, my first real friend.” Grishchuk took out a wrinkled apple from under the cart seat. “Eat it,” he told me, “please, eat it.”’ A quiet, indirect, apparently inconsequential, Chekhovian close. But the soothing gesture is germane. Grishchuk, the subordinate, is consoling his friend and superior, whose feelings have been wounded in parallel to Dolgushov’s physical wounding. The wrinkled apple is a token of friendship. It also carries an edge of impatience, a hint of rebuke, as the lowly driver confronts the narrator’s self-indulgent egotism with an act of self-sacrifice, the giving up of the precious apple.

Consider ‘A Letter’, a four-page masterpiece about the civil war. In it, a father butchers his son Fyodor and is in turn butchered by another son, Semyon. The narrative is contained in a letter dictated to Babel by yet a third son, Vasily. The appalling cruelties are matched by the calculated subtlety of the narrative’s ironies. The main thrust of the letter is prefaced by the tenderest of digressions – tenderness which, as it turns out, indicates a lack of affect. It concerns Stepan. It is several unpunctuated sentences before we realise that Stepan is not a child but a horse. ‘Write to me a letter about my Stepan – is he alive or not, I beg you to look after him and to write to me about him, is he still scratching himself or has he stopped, but also about the scabs on his forelegs, have you had him shod, or not?’ The father makes his first, unfavourable appearance in the context of the horse: ‘I beg you, dearest Mama, Evdokiya Fyodorovna, to wash without fail his forelegs with the soap I hid behind the icons, and if Papa has swiped it all then buy some in Krasnodar, and the Lord will smile upon you’ (my italics). The tenderness privileges the horse over the human being.

Like the peasant boy this soldier is, he then describes the local inhabitants, the crops, the poor soil, before broaching the story of his father’s brutality: ‘In these second lines of this letter I hasten to write you about Papa, that he hacked my brother Fyodor Timofeyich Kurdyukov to pieces a year ago now.’ When the revenge is achieved, it is Greek in its restraint: ‘Semyon sent me out of the yard, so that I cannot, dearest Mama, Evdokiya Fyodorovna, describe to you how they finished off Papa, because I had been sent out of the yard.’ Who could have guessed that a null tautology – ‘because I had been sent out of the yard’ – in conjunction with the formulaic endearment and patronymic would manage to convey so vividly the hideously inept offstage murder? In the hobbled clumsiness of the prose, in the awkward, inappropriate expression of affection, Babel’s oblique mimesis is horrifyingly exact. The letter concludes with other ‘news’ about the wet town of Novorossisk – which situates the letter’s moral tone somewhere between the affectless and a misplaced sense of naive politesse.

(Babel is uniformly good on letters: ‘Trunov scrawled gigantic peasant letters on a crookedly torn piece of paper’ (my italics); Khlebnikov ‘asked me for some paper, a good thirty sheets, and for some ink. The Cossacks planed a tree stump smooth for him, he placed his revolver and paper on it, and wrote till sundown, filling many sheets with his smudgy scrawl.’ His comrades tease him as ‘a regular Karl Marx’.)

The story of Vasily’s letter concludes with a family photograph, showing his father and ‘next to him, [his mother] in a bamboo chair, a tiny peasant woman in a loose blouse, with small, bright, timid features. And against this provincial photographer’s pitiful backdrop, with its flowers and doves, towered two boys, amazingly big, blunt, broad-faced, goggle-eyed, and frozen as if standing at attention: the Kurdyukov brothers, Fyodor and Semyon.’ What is the photograph telling us? Beyond, that is, the blunt irony of the photographer’s ‘flowers and doves’ and the record of family togetherness? The photograph is eloquent about how little it is telling us. It confesses its fraud, its nugatory pretence. It keeps us out like that earlier repetition: ‘because I had been sent out of the yard.’

‘A Letter’ is a story perfect in every particular – and therefore rare in Babel’s consistently imperfect œuvre. And the cause of the imperfections? So far selective quotation of the high points might imply that Babel is a realist – ‘sisters with their little moustaches’ – whereas he is only partly a realist. He has a fatal hankering for poetry, too. By which he understands something essentially anti-realist. Babel was a writer, uneasy with the idea of documentary. The editor of this sumptuous and thorough Complete Works, the writer’s daughter, Nathalie Babel, emphasises in her headnote to the Red Cavalry stories that they were, ‘as Babel himself repeatedly stressed, fiction set against a real backdrop’. Art, then, not reportage. According to Henry Gifford, Babel was a great reviser, taking twenty-two drafts to finish ‘Lyubka the Cossack’: he didn’t want posterity to think him a passive onlooker and recording stenographer-angel merely taking down dictation. Lest we should undervalue the writing itself, Babel’s opus includes a number of characteristically Russian over-statements about the writing process. They are fondly quoted by credulous admirers like Cynthia Ozick, who here contributes a breathless, brainless introduction. ‘I spoke to her of style,’ he writes in ‘Guy de Maupassant’, ‘of an army of words, an army in which every weapon is deployed. No iron spike can pierce a human heart as icily as a period in the right place.’ This self-vaunting credo might carry more weight were it not for another obiter dictum about repetition on the same page: ‘When a phrase is born, it is both good and bad at the same time. The secret of its success rests in a crux that is barely discernible. One’s fingertips must grasp the key, gently warming it. And the key must be turned once, not twice.’ This is sound, subtle, tactful – and violated by Babel in the previous paragraph, where we are twice told that the maid had ‘pointed breasts’. ‘Debauchery had congealed in her gray, wide-open eyes,’ Babel confides on one page, only to write on the facing page, ‘turning away her eyes in which debauchery had congealed’.

Poetry was intended as a stay against the accusation of reportage, the lowest form of realism. In practice, for Babel, ‘poetry’ meant overwriting, flirtation with non-sense, exaggeration, deliberately chosen imprecision, anti-realism. And it is fatal for many of the stories. In an early story, ‘Odessa’, Babel complains that in Russian literature ‘there haven’t been so far any real, clear, cheerful descriptions of the sun.’ His stories are, among other things, a sustained effort of reparation and overwriting. Here is a partial cull: the sun ‘poured into the clouds like the blood of a gouged boar’; ‘the sun soared up into the sky and spun like a red bowl on the tip of a spear’; ‘the sky changes colour – tender blood pouring from an overturned bottle’; ‘the dying sun in the sky, round and yellow as a pumpkin, breathed its last rosy breath’; ‘a timid star flashed in the orange battles of the sunset’; ‘we rode toward the sunset, its boiling rivers pouring over the embroidered napkins of the peasants’ fields’; ‘in his yard, the sun was tense and tortured with the blindness of its rays’; ‘the cross-eyed lantern of the provincial sun’. Every one a dud. You can have too much of a bad thing.

Nor is the moon exactly ignored: ‘the snaking moon’; ‘only the window, lit up by the fire of the moon, shone like salvation’; the moon is twice described as ‘a nagging splinter’, which for once has a kind of precision. Otherwise, Babel seems bent on the widest gap possible between tenor and vehicle – as a guarantee of poesis. Now and then, success seems close. For instance, there is a kind of metaphoric counterpoint between the cool of evening and a mother tending a fevered child: ‘The evening wrapped me in the soothing dampness of her twilight sheets, the evening placed her motherly palms on my burning brow.’ Maybe it sounds less cluttered and more natural in Russian. In English, the nursing details, the dampened sheets to lower the temperature, simply overwhelm the cool crepuscular half of the comparison. Then there is the judiciously indecorous, anti-poetic comparison I associate with Pasternak: ‘the sunset was boiling in the skies, a sunset thick as jam.’ Again, the two-stage comparison with jam-making is unwieldy and faintly argumentative. I prefer the precisely Pasternakian comparison, ‘the kerosene-coloured night of Baku’, or the real oddity of the word ‘implausible’ in this figure: ‘the fire of the sunset swept over him, as crimson and implausible as impending doom.’

But mostly the implausibility lies in the metaphors and similes themselves. ‘Bullets unfurled like string along the road.’ Bullets bring out the worst in Babel: ‘the bullets plunge into the earth and writhe, quaking with impatience’ (my italics). Any metaphor with an olfactory element is invariably solipsistic and inscrutable: ‘her sponge cakes had the aroma of crucifixion’; ‘a sour odor rose from the ground, as from a soldier’s wife at dawn’; ‘I stink like a slit udder’; ‘a red-headed widow, who was drenched with the scent of widow’s grief’; ‘the cadaverous aroma of brocade’; ‘Sashka’s body, blossoming and reeking like the meat of a slaughtered cow’.

There is no single rationale for these overblown figures, rather a variety of contributing reasons. As well as the Russian tradition of the opaque, apparently unjustified comparison, there are two other causes to take into account: the potent example of the epic simile and the vernacular tradition. The vernacular tradition employs exaggeration as its stock in trade: think of Huckleberry Finn retailing (with an inflection of doubt) an image of his father’s, when a man who has fallen from a high roof is buried not in a coffin but between two barn doors. It might be the Beano. You can identify this bent in Babel’s imagery now and again. For instance, when Benya Krik fights his father, the favoured figure of speech is ‘he shuffled his father’s face like a fresh deck of cards.’ In English pub argot, the equivalent euphemism would be ‘to rearrange someone’s features for the worse’. What makes these phrases both popular and vulgar is their artifice, their frank contrivance. Raymond Chandler’s Marlowe is, like Babel, equally given to suave, original variations of this wise-cracking demotic.

‘Konkin’ subtly but self-consciously comments on the vernacular. In this story, a Cossack pursues a Polish officer whose dignity will not allow him to surrender to anyone other than the supreme commander, Budyonny. Exasperated, the Cossack declares his civilian identity and demonstrates it. He is a ventriloquist from Nizhny. And the whole story is ventriloquised by Babel, who is interested in the anecdotal method of the anonymous soldier. ‘Konkin, the political commissar of the N Cavalry Brigade and three-time Knight of the Order of the Red Flag, told us this story with his typical antics during a rest stop one day’ (my italics). The demotic style is antic. Doors don’t simply open. They burst open. ‘Barbara Stepanovna turned purple.’ ‘Her voice boomed like mountain thunder.’ ‘The snake of his peasant grin slithers across his rotten teeth.’ Exaggeration is an implicit declaration of class solidarity.

Writing of the Red Cavalry, Babel was aware of his political duty to heroise, even as he unflinchingly and critically depicted the casual barbarities of his Cossack comrades. I believe that Babel was consistently subversive. ‘And in a loud voice, like a triumphant deaf man, I read Lenin’s speech to the [illiterate] Cossacks.’ The speech is there for the political commissar. The ‘triumphant deaf man’ is there for the reader alert for irony. In ‘Salt’, another ventriloquised story, the narrator throws a female smuggler off a train, then shoots her. The story ends with this affirmation of Bolshevism: ‘we will deal relentlessly with all the traitors who pull us into the pit and want to turn back the stream and cover Russia with corpses and dead grass.’ The speaker, Nikita Balmashov, has just left the corpse of the woman by the side of the railway. This contradiction, that the revolution brings destruction indistinguishable from that of the former tyrants, is one to which Babel returns time and again.

The epic simile is part of the iron necessity to heroise, lest the ironies become transparent. And the epic simile carries the requirement of radical indirection. Where the normal simile insists on likeness, the epic simile prescribes differentiation. So Savitsky rises ‘splitting the hut in two like a banner splitting the sky’. The commander’s ‘long legs looked like two girls wedged to their shoulders in riding boots’. In Babel’s prose, the expansiveness of the epic simile proper is cognate with demotic hyperbole: ‘he ran after [the prisoners] and gathered them under his arms, the way a hunter grips an armful of reeds and pushes them back to see a flock of birds flying to the river at dawn.’ ‘And Madame Gorobchik stood by her husband’s bed like a mud-drenched crow on an autumn branch.’ Only occasionally does Babel allow the epic simile its iota of irony: ‘The damp mold of the ruins blossomed like a marble bench on an opera stage. And I waited with anxious soul for Romeo to descend from the clouds, a satin Romeo singing of love, while backstage a dejected technician waits with his finger on the button to turn off the moon.’

Yet, after all the allowances and explanations, much remains that is simply indigestible – confused, arbitrary, affected, contrived, arch and preening. ‘My husband brings me firewood as wet as newly washed hair.’ ‘Blue roads flowed past me like rivulets of milk trickling from many breasts.’ ‘I rise from my bunk from which sleep had run like a wolf from a pack of depraved dogs.’ ‘You have laid impetuous rails across the rancid dough of Russian prose.’ Babel’s first Red Cavalry story, the two-page ‘Crossing the River Zbrucz’, has an ending that is not unforgettable but inescapable – the account of the dead Jew with his face ‘hacked in two’. But almost equally inescapable is the melodrama of the sun ‘rolling across the sky like a severed head’, the ‘snaking moon’ – and the Jews who ‘hop around in silence, like monkeys, like Japanese acrobats in a circus, their necks swelling and twisting’. My italics mark a physiological impossibility – an impossibility which is bound to mar the authenticity, the realism, on which Babel’s uncertain claim to greatness is founded.

The Complete Works of Isaac Babel, edited by Nathalie Babel and translated by Peter Constantine (W. W. Norton & Co., 2002).

Derek Walcott’s Poetry

(2000)

Plagiarism is, of course, the original sin. But a still more original version is copying yourself. There are many examples of self-plagiarism in Derek Walcott’s extensive œuvre. On at least six occasions, Picasso is reported denouncing self-plagiarism as abject: ‘copying others is necessary, but what a pity to copy yourself,’ he told Dor de la Souchère.

Others first. Walcott’s stated position on the anxiety of influence – that you could just as easily say ‘the influence of anxiety’ – is as unequivocally evasive as you might expect from a writer so clearly, lastingly and fatally touched by Dylan Thomas. ‘The Bounty makes clear Walcott’s continuing relationship to Dylan Thomas’s verse,’ writes Bruce King, his sympathetic biographer. He must mean Walcott’s ‘snail-horned steeples’ which owe so much – everything, in fact – to Thomas’s ‘Poem in October’: ‘the sea wet church the size of a snail / With its horns through mist.’

But Thomas’s legacy to Walcott isn’t simply the odd purloined image or two – or more – but also the considered embrace of fuddled syntax as a chosen poetic method. When T. S. Eliot said that the modern poet must ‘dislocate if necessary, language into his meaning’, Thomas evidently took Eliot too literally. There is in Thomas and Walcott a great deal of wilfully crippled language. Bruce King has this to say: ‘some of [Howard] Moss’s other comments point to difficulties that are so common to Walcott’s writing that they are part of his style. There are words with uncertain reference which look forward and backward, there is a lack of verbs, the syntax may be erratic, punctuation is erratic in terms of clarifying meaning.’ The amount of incompetent exposition in, say, Omeros is astonishing.

There are not only loose ends of plot. Hector loses his canoe in a storm on page 50, only to sell it on page 116 to buy his Comet car. Helen has stolen Maud’s yellow frock on page 31, even though Maud Plunkett has altered it for Helen on page 29. On page 64 we are told (how reliably?) that the dress was a gift to Helen which Maud forgot. After all, Helen has definitely nicked towels from the Plunketts. There are also frequent passages where syntax and grammar seem designed to obstruct and occlude. Here are two related passages, dealing with Warwick Walcott, the poet’s dead father: ‘Out on the sidewalk the sunlight drained like a print / of a postcard flecked with its gnawing chemical / in which there was light, but with a sepia tint’ (my italics). Walcott wants to say, I think, that the scene outside looks like a faded sepia postcard. This is Warwick Walcott in full fatherly spate: ‘But before you return, you must enter cities / that open like The World’s Classics, in which I dreamt / I saw my shadow on their flag-stones, histories / that carried me over the bridge of self-contempt, / though I never stared in their rivers, great abbeys / soaring in net-webbed stone, when I felt diminished // even by a postcard’ (my italics). The sense nearly survives its setting forth. Warwick Walcott prophesies his son will encounter at first hand the European culture the father only read about. He recalls his sense of inferiority and insularity, which could be exacerbated by a postcard of Europe, and yet was soothed by his reading. Reading his son, though, you start to dread the apparently helpful, but actually phantom connectives. In which. The syntax is purely gestural. It is no accident that my grammar-check – admittedly a crude instrument for assessing poetry – has underlined that entire quotation. It doesn’t make sense.

Though Dylan Thomas (‘past sleep-tight houses’) is the main Other in Walcott, there is, via Thomas, Hopkins: ‘in the indigo dark before dawn’ is indebted to Hopkins’s ‘Moonrise’. Walcott is also touched by Auden, Yeats, Lowell, Heaney and Brodsky – less permanently, but so extensively that one is almost embarrassed by his lack of guile. The clichéd colonial paradigm of invasion and conquest has been fulfilled aesthetically. Odd, given that Walcott’s pronouncements on the colonial past and its role in the present are so eminently sensible. Drawing on the Caribbean experience, he sees that no one and no race is without guilt – what happened, he asks, to the aboriginal Aurac people? Forget the past, then. Prepare, guiltlessly, to take advantage of English literature and all its language has to offer. In the event, though, English literature seems to have taken advantage of him – to have imposed its poetic practitioners successfully, absolutely.

Derek Walcott’s reputation rests primarily on three works: Another Life (1973), ‘The Schooner Flight’ (1979) and Omeros (1990). The last, a work of over 300 pages, written over three years, published in 1990, is widely seen as the work that secured him the Nobel Prize in 1992. This review will concentrate therefore on Omeros. How good is it?

Walcott has always been a striking phrase-maker, and there are wonderful, memorable touches throughout Omeros. ‘Then I heard patois again, as my ears unclogged’ – whenever Walcott turns to dialect, ‘then everything fit’. You are quenched and convinced by the authority, by the authenticity – ‘Girl, I pregnant,/ but I don’t know for who.’ Now and then, of course, there are poetic flourishes rhetorically beyond the speakers. ‘Their leaves start shaking / the minute the axe of sunlight hit[s] the cedars,’ for example. This is a problem intrinsic to vernacular. How does the writer accommodate his linguistic gifts within the cramped, if fresh, givens of the vernacular? And unquestionably Walcott has those gifts: the egret’s ‘one rusted cry’, the iguana’s ‘slit pods of its eyes’, ‘sunrise / trickled down its valleys’, ‘whales burst into flower’, ‘the wick of the cypress charred’, ‘the gold sea / flat as a credit card’, ‘and the only sound is the hot, lazy drum of the sea’ (my italics). Walcott’s metaphoric resource is widely celebrated – though a phrase like ‘a bouquet of spume’, if 200 pages away from ‘whales burst into flower’, still looks repetitious – parsimonious trope rotation.

In fact, surprisingly, the best Walcott is the plainest, those instances of straight observation, of unadorned directness: for Philoctete’s perpetual shin-sore, ‘like a radiant anemone’, there is ‘the usual medicine for him, a flask of white / acjou, and a jar of yellow Vaseline’ (my italics). The colour is careful. That ‘anemone’ is fine, too, but weakened when, eleven pages later, we read that ‘His knee was radiant iron’ – an echo undiminished by the difference senses of ‘radiant’. Walcott is good, also, on the way the erotic situates itself in the ordinary without being diminished – even perhaps enhanced. His St Lucian Helen of Troy, the casus belli between the fishermen Hector and Achille, is seen on several occasions, perhaps too many, ‘swinging a plastic sandal’ – a credible goddess, who, when she leaves Achille’s exhausting jealousy for Hector, leaves ‘a hair-pin / stuck in her soap dish’. Though there are fine phrases which, as it were, straddle the literal and the metaphoric – ‘The reek of the beach / was rimmed with a white noise’ – the more literal are the better. Walcott’s much vaunted metaphoric facility has its negative side. Sometimes, he simply can’t say things simply. In Omeros, there is precious little crying that isn’t precious: ‘Dew was filling my eyes’, ‘my dewy gaze’, ‘a coming rain hazing his pupils’, ‘both of them wept / the forgiving rain of those who have truly loved.’ It could be Enoch Arden.

Then there are the stars. Plainly: ‘From night-fishing he knew the necessary ones, / the one that sparkled at dusk, and at dawn, the other.’ This is on a par with the flat effectiveness of ‘she [Maud Plunkett] took off her damp gardening hat // and lay down on the faded couch, she loosed her bodice / and blew down to her heart.’ This factuality has an irrefutability shared by the lover who taps Walcott’s knuckles in the morning by way of goodbye – by way of affection, of acknowledgement, by way of saying how little need be said. Add to these the mourners who ‘walk home / to their rusted villages, good shoes in one hand’ (my italics), or the ‘nut-littered troughs’ of the sea, or bank tellers pausing to hear the Angelus – ‘one wet fingertip / drying before it moved on to turn the next leaf’.

By comparison, the metaphors can seem contrived, muscle-bound, if powerful: in ‘The Schooner Flight’, we read ‘nail holes of stars in the sky roof’, conscious of the i’s in the comparison being dotted and the t’s being crossed. As we are in Another Life, where we read for the first time, ‘the usual smoky twilight / blackened our galvanized roof with its nail holes of stars.’ The latest sighting was in The Bounty: ‘the stars that nail down their day’. You begin to wonder about Walcott’s famous fecundity.

Which brings us to the subject of repetition in Walcott’s poetry.

In Omeros, ‘the corrugated iron / of the sea glittered with nailheads’. It is raining. In ‘The Schooner Flight’, it isn’t raining, otherwise nothing has changed: ‘the cold sea rippling like galvanize’. In Omeros, ‘the sunrise was heating the ring of the horizon’, whereas in ‘The Schooner Flight’ ‘the sun / heat the horizon’s ring.’ In The Arkansas Testament, ‘A Propertius Quartet’, bafflingly, ‘the sea’s ring turned red with heat / under bubbling Colombian coffee.’ Then there are the asphalt roads which produce a curiously persistent comparison: in Omeros, ‘I smelt the drizzle / on the asphalt leaving the Morne, it was the smell // of an iron on damp cloth.’ This Proustian equation had already been set down in ‘The Schooner Flight’: ‘every hot road, smell like clothes she just press.’ But even before that, Another Life spoke of ‘The smell of drizzled asphalt / like a flat iron burning’. In the post-Nobel The Bounty, the trope recurs: ‘a singed smell rose / from the drizzling asphalt’.

Omeros is an extraordinary anthology of repetition.

Initially, one is dazzled by the metaphoric brilliance of Walcott’s comparison of the sway of the sea to the swoon of scales: ‘the horizon’s glittering scales’. Then you recall a prior, clumsier sighting, 240 pages previously: ‘each brass basin / balanced on a horizon, but never equal’. And then it all comes back: in Another Life, ‘the steel, silver scales of the sea’. It is possible, however, that these ‘scales’ are the more obvious fish scales, as they are in The Bounty: ‘the sea shone / like its fish, the scales danced.’ Nothing to do with weights and measures.

On pages 98 and 321, there are ‘asterisks of rain’. On page 294, the starfish is an asterisk. On page 7, mosquitoes on his arms are ‘flattened to asterisks’ by Achille. On page 224, we meet ‘asterisks of bulletholes’.

On page 38, the market discloses ‘the iron tear of the weight’ and on page 324 ‘the copper scales, swaying / were balanced by one iron tear’.

Then there are the Homeric lances, flung everywhere to create a spurious, overworked ‘classicism’: page 9 ‘the lances of oars’, page 230 ‘with lances for oars’, page 292 ‘lance of an oar’; page 15 ‘lances of rain’, page 50 ‘lances of rain’, page 149 ‘the rain’s lances’; page 51 ‘the lances / of a flinging palm’, page 31 ‘the palms’ rusted lances’, page 33 ‘copper spears of the palms’; page 35 ‘lances of sunlight’, page 297 ‘a lance of sunlight’. Not to mention ‘lances of yachts’ or ‘the feathered lances of cane’.

We could list all the comparisons of the sea to lace, or the heat haze as wires, but the list would be, well, epic ... Instead, what about the comparison of rain to nails? Page 50: ‘the crash / of thousands of iron nails poured in a basin // of rain on his tin roof’. Page 222: ‘pouring tin nails on the roof’. The sea as parchment recurs on pages 3, 155 and 282. Of course, you can’t have such egregious repetition without a built-in excuse – and Omeros duly supplies one. Page 96: ‘and none noticed the Homeric repetition / of details, their prophecy.’

None noticed. Hold on a second there. Or do I mean a third, or a fourth.

Of course, the poem does have deliberate reprises: ‘This was History. I had no power to change it. / And yet I still felt that this had happened before.’ Often it has. There is a motif which links slavery to the work of ants. And when the slavers come to Achille’s African village, the tableau of destruction depicts a mongrel and child in the street. Later in the poem, when the Sioux are raided, the child and mongrel motif is deliberately redeployed to make the link. But, equally obviously, this doesn’t excuse the swarm of repetition in Omeros because many of those repeats are further repeated outside the poem. Repetition is a kind of disease in Walcott’s work: in Another Life the narrator ‘heard the grey, iron harbour / open on a seagull’s rusty hinge’ and a hundred pages later ‘Day pivoted on a seagull’s screeching hinge.’ Is it indolence or inadvertence or pure incompetence?

Elizabeth Bishop, a peerlessly controlled, precise poet, memorably compared a basin to the moon in ‘The Shampoo’. The whole stanza is memorable for its effortlessly sustained metaphor:

The shooting stars in your black hair

in bright formation

are flocking where,

so straight, so soon?

– Come, let me wash it in this big tin basin,

battered and shiny like the moon.

Walcott helplessly shoplifts her image and wears it out with overuse: page 12, ‘stuck like a basin, / the rusting enamel image of the full moon’; page 235, ‘the moon’s cold basin’; on page 273, ‘Moon-basins flashed in the riverbed.’

Clearly, there is a difference between Elizabeth Bishop’s innate metaphoric tact and Walcott’s unwieldy, wordy procedures. Where Bishop’s analogy with the night sky is beautifully unforced, yet sustained, Walcott’s extended metaphors arrive with the air of brazen, bald contrivance one associates with the cod TV host Alan Partridge. A nudge too far. My italics in the following quotations: ‘roosters, their cries screeching like red chalk / drawing hills on a board’; ‘and a breaker arched with a sound like tearing cloth / ripped down the stitched seam, a sound Mama make sewing // when, in disgust, she’d rip the stitches with her mouth’; ‘The lights stuttered in the windows // along the empty beach, red and green lights tossed on / the cold harbour, and beyond them, like dominoes / with lights for holes, the black skyscrapers of Boston.’ The sound of Walcott painfully explaining. One last absurd unified field of agricultural imagery:

he had counted the clustered berries on the nose,

noted the eyebrows’ haystacks, the dull canal gaze

of his reflection, the forehead’s deep-ploughed furrows,

the bovine leisure with which he turned away eyes

stupefied by distances ...

Could Walcott have a Dutch farmer in mind? Just a thought.

It is interesting to compare repeats in which the second version achieves a crispness denied the initial cluttered attempt. The hurricane in Omeros, Chapter IX provides instances of Walcott’s writing at its worst:

Lightning, his stilt-walking messenger, jiggers the sky

with his forked stride, or he crackles over the troughs

like a split electric wishbone. His wife, Ma Rain,

hurls buckets from the balcony of her upstairs house.

She shakes the sodden mops of the palms and once again

changes her furniture, the cloud-sofas’ grumbling casters

not waking the Sun ...

This epic of plodding ingenuity, of deranged decorum, of laboured proliferation, leaves one longing for the brilliantly prosaic narration of Ma Kilman’s cure of Philoctete, say, or the amusing, if irrelevant chapters about the political aspirations of Statics. How much more lightly the metaphors might be managed is demonstrated by Walcott himself: ‘Lightning lifted his stilts over the last hill.’ Similarly, there is the thumbsiness of ‘in the grey vertical forest of the hurricane season’ and the perfect economy of the later ‘rain was an unshifting thicket’.

Some wordiness is forgivable. Heaney’s brilliant comparison – ‘fungus plump as a leather saddle’ – waves aside the pedantic objection that, since all saddles are leather, ‘leather’ is tautological. The comparison is just, surprising, swift. It is self-explanatory and brilliant – obvious once it is pointed out. It requires no justification, no argumentation. Not that Heaney is entirely immune, though he is an infinitely more accomplished writer than Walcott. In The Spirit Level there is a terrible meddling moment of Walcottian over-insistence, a failure of tact: ‘and the angler’s motorbike / Deep in roadside flowers, like a fallen knight’. The image is perfect, did it stop there. Alas, it continues: ‘Whose ghost we’d lately questioned: “Any luck?”’ The cause here seems to be the rhyme scheme, as much as anything else.

The rhyming in Omeros has been widely acclaimed, particularly by Brad Leithauser in the New Yorker. The currently high value placed on rhyme seems to me much exaggerated. Christopher Reid’s poem ‘Two Dogs on a Pub Roof’ manages effortlessly to rhyme the same word exactly a hundred times. It is, I think, an ironic comment on the facility possible, given the latitude permitted. What was once a minor skill is now absurdly easy. Many of Walcott’s rhymes are outrageous, following the example of Brodsky. The Bounty gives us ‘even a’, ‘novena’ and ‘when a’. Omeros is an encyclopedia of brazen botches: ‘jacket’/ ‘back, it’; ‘tin-stealer’ / ‘Achille, the’; ‘verandah’ / ‘Morne, the’; ‘weather’ / ‘This year, the’; ‘farmer’ / ‘uniform, a’; ‘demeanour’ / ‘seen the’; ‘savannah’ / ‘and the’; ‘were the’ / ‘warrior’; ‘Winchester’ / ‘was the’; ‘flag-pole’ / ‘uphol-[stered]’. I could go on. The point is neither the ingenuity, nor the licence – though Hopkins and Browning have been scolded for greater ingenuity and less licence. The point is the continuous havoc Walcott’s rhymes impose on his lines. Omeros is an epic of ugly lines, each one of which is individually allowable, but cumulatively disastrous:

... a fur monkey over the dashboard altar

with its porcelain Virgin in flowers and one arm

uplifted like a traffic signal to halt. Her [my italics]

Again:

... palm-fronds talking

to each other. It was one of the mysteries

of advancing age to like those tempestuous

gusts that hyphenated leaves on a railed walk, in- [my italics]

stead of keeping things in place and their proper use.

These two examples must stand for many where the integrity of the line is systematically violated.

In an interview for New Letters, Walcott said of Omeros that ‘he had not had a plot in advance’ and that ‘his main aim as a writer was to give a clear picture of life in the Caribbean, especially its beauty.’ Both these statements are fatal for the poem – which suffers from event-famine and an overdose of description. Who would have believed that all that lush landscape could be so monotonous, so relentless? Omeros is also without form. Anything goes in. Walcott goes to Lisbon in 1988 to attend a Wheatland Foundation conference, paid for by Anne Getty, and a touristic section finds its way into Walcott’s epic. The slave trade is the slender link, the pretext for pages of picturesque watercolours in words.

There are three main narratives in Omeros: the love triangle of Helen, Hector and Achille; the Maud and Dennis Plunkett story which culminates in Maud’s death; and the real but masked narrative of Walcott’s own life. The last is potentially the most interesting, but the personal material, as opposed to the tourism of the international writer, is flinchingly unfrank. It seems to touch on Walcott’s tormented relationship with his third wife, Norline Metivier. I deduce this from Bruce King’s ultra-discreet life, which commendably guards the intimate detail of Walcott’s biography, while disclosing the bare minimum of necessary facts. Walcott himself in Omeros mentions no names – and his insufferably coy treatment of sexuality is uniform with its treatment in the fictional narrative. Think of Larkin’s tough candour in ‘Love Again’ – ‘Love again: wanking at ten past three’ – and compare Walcott’s biblical, euphemised hand-job: ‘House whose rooms echo with rain, / of wrinkled clouds with Onan’s stain’. Sex throughout Omeros proves intractable for Walcott – especially masturbation. Helen, apparently to bring back Achille in some unexplained mystic fashion, masturbates in Chapter 29:

... The hand was not hers

that crawled like a crab, lower and lower down

into the cave of her thighs, it was not Hector’s

but Achille’s hand yesterday. She turns slowly round

on her stomach and comes as soon as he enters.

The last line makes Walcott’s cultural difficulty with masturbation clear. It isn’t the real thing. Helen can come only with a man – he enters the room and enters her body too. But an innocent reader could be forgiven for not knowing what was going on precisely – given that crab and all that prestidigitation of hands. This is an early fuck in Omeros, with sperm – I think: ‘we swayed together in that metamorphosis / that cannot tell one body from the other one, / where a barrier reef is vaulted by white horses.’ I could easily be wrong. This is an even earlier fuck: ‘She lay calm as a port, and a cloud covered her / with my shadow.’ I could just as easily be wrong again. And this is Walcott fantasising a fuck with a Polish waitress in Toronto. He is reading at Greg Gatenby’s Harbourfront. He is lonely and horny. It comes out as poetry: ‘snow draped its bridal lace over the raven’s-wing sheen. / Her name melted in mine like flakes on a river / or a black pond in which the wind shakes packets of milk.’ Welcome back, in which. No wonder one of the three alleged charges of sexual harassment against Walcott has been so difficult to resolve. Walcott has never denied his words – only the meaning of what he said.

Bruce King has a brave try at unifying the bricolage and brocante of Walcott’s epic – but he isn’t convincing. The theme of Book I is ‘that life consists of wounds’ – of Philoctete’s shin, of Dennis Plunkett’s head wound, and of ... Apparently, the quarrel between the Plunketts is a kind of wound. As is, apparently, Helen quitting her job after being insulted by a tourist. Initially plausible, these ‘themes’ do not in fact engross the detailed narrative – where, in the words of Sinatra, anything goes. Including some appallingly twee poetic fictions – the bogus epicese of ‘the surf abated / its sound, its fear cowering at the beach’s rim’ and the weeping porcelain Madonna on Hector’s dashboard when he is killed in a road accident. Worse than these is the encounter in Ireland with the ghost of James Joyce – an ineffably vulgar copy of Heaney’s Dante-influenced encounter with Joyce at the conclusion of Station Island. Where Heaney has Joyce hitting a litter basket with his ashplant, Walcott’s account sinks under the weight of its clichés – the CNN version of the Troubles and the genial company of ‘The Dead’ singing along with their author, ‘his voice like sun-drizzled Howth’. This isn’t poetry at all. It is the Dante Experience Franchise trading at a loss.

Bruce King’s biography is the first and probably the last full-length account of Walcott’s life. It is unintrusive, well disposed, charitable to its subject – and finally, reluctantly, critical of the man and his work. It feels intermittently as if there are two books, not one – the authorised and the rebellious.

King is continuously interesting about Walcott’s troubled relationship to his own blackness. He is authoritative and sometimes tedious on Walcott’s drama, a subject he has already written about. His eagerness to praise Walcott – the biography’s worth being grounded on his subject’s artistic stature – means that his judgements begin to bite only in the second half. Before that, King’s criticism is credulous and a bit budget – for example, the meaningless statement that ‘long before he met Joseph Brodsky, Walcott was already at heart a Russian writer.’ A Russian writer like whom? – Mayakovsky, Pasternak, Goncharov, Griboyedev, Pushkin?

Now and then, though, a piqued biographer lets slip judgements both subversive and true. We learn that bits of Walcott’s prose autobiography went straight into Another Life and ‘became marvellous poetry. Once Walcott moves beyond journalism his prose often becomes poetic – mood, impressionism, epiphanies, and posturing’ (my italics). King proves to be rightly uneasy with Walcott’s easy resort to ‘large gestures’ – ‘running together slavery, imperialism, the attempted extermination of the Jews, the war in Vietnam, and personal sins, loses their specificity, their difference, the reality of what has been done.’ History as simplification, then.

For King, the advent of Brodsky isn’t an unqualified benign influence: ‘this contempt of democratic levelling, assertion of improbabilities, and use of tangential replies was often Walcott’s manner during these years. It is rather grand, probably influenced by Brodsky’ (my italics). On Walcott’s appalling critical prose – prose that can refer, hilariously, ignorantly, to ‘Eliot and Pound in their Byronic romanticism’ – King is divided. On the one hand, ‘his best essays are unusually rich in style, in symbolism, in ellipses, epiphanies; they are, in fact, poetic, deep, rich.’ On the other hand, ‘as I look through fragments and drafts of Walcott’s autobiographical pieces and essays, I am struck by the digressiveness, by the waffling about and the lack of economy.’ I suggest that these two views are saying the same thing – politely, then truthfully.

Finally, before I forget – those ‘slit pods’ of the iguana that I praised. Compare ‘crocodiles, slitting the pods of their eyes’ on page 133. In Omeros there are seven instances of slitted eyes. At the last count.

Bruce King, Derek Walcott: A Caribbean Life (Oxford, 2000).

Raymond Carver

(2009)

In 1967, Raymond Carver and his wife Maryann filed for bankruptcy protection. Carver was drinking heavily. He decided to train as a librarian and enrolled into the master’s programme at the University of Iowa’s School of Library Science. By June, he had abandoned this plan and was hired as a textbook editor at Science Research Associates in Palo Alto, California. It was Carver’s first white-collar job. Carver’s story ‘Will You Please Be Quiet, Please’ was selected for Best American Stories 1967. In 1968, Near Klamath, Carver’s first book of poems, was published in the spring. So, literary achievement, if on a small scale.

But probably the most important thing in Carver’s life had already happened. Late in 1967, he was introduced to Gordon Lish, the founder editor of Genesis West, an avant-garde magazine. Lish was also working for a textbook publisher in Palo Alto. In 1969, Lish became fiction editor at Esquire magazine and in November wrote to Carver asking for stories. (Lish’s shift from avant-garde to mainstream was ironised in his 1971 essay ‘How I Got to be a Big-Shot Editor and Other Worthwhile Self-Justifications’ – that title, a boast and a knowing, wry disclaimer, gives you some idea of how clever Lish is.) In 1970, Lish line-edited Carver’s story ‘Neighbors’ and accepted it for Esquire. Carver was grateful – for acceptance and editing.

By 1976, Lish’s assiduous promotion of Carver paid off. McGraw-Hill, under the Gordon Lish imprint, published Carver’s first book of fiction, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? The twenty-two stories had all been previously published in periodicals and were further edited by Lish, with Carver’s approval. In this year, Carver was hospitalised for acute alcoholism and wound up in Duffy’s, a residential treatment centre in the Napa Valley. Did I mention that in 1974, Carver and his wife filed for bankruptcy protection a second time? Well, I did now.

In 1980, Carver, separated from Maryann, set up house with poet and Guggenheim Fellow Tess Gallagher in El Paso, then Syracuse in upstate New York. Carver gave a manuscript to Lish, now an editor at Knopf, and Lish edited the stories so intensively that the original was halved in length. On 8 July 1980, Carver wrote a despairing letter to Lish, insisting that, unless the original text was restored, publication of What We Talk About When We Talk About Love should be cancelled. Part of Carver’s problem was that several other writers, like Tobias Wolff and Stephen Dobyns, had seen the originals. They would know what Lish had done.

In the event, publication went ahead and Carver’s name was made. Though thereafter Carver was confident enough to resist Lish’s editing, ever since, there have been rumours that Gordon Lish was responsible for everything valuable in Carver’s work. The editors of the Library of America Collected Stories (not complete) have chosen to publish Carver’s original manuscript (Beginners) alongside Lish’s edit (What We Talk About When We Talk About Love). They have done so at the urging of Carver’s widow, Tess Gallagher, who feels the original manuscript is superior to Lish’s edit. It isn’t. It is manifestly inferior. Lish was an editor touched with genius.

But does this mean that Carver was untalented? Think of Ezra Pound’s peerless and ferocious editing of The Waste Land. Every edit an improvement – and Eliot’s reputation unaffected. Think of Charles Monteith’s editing of the original typescript of Lord of the Flies: no one would wish back the thirty introductory descriptive pages of nuclear war cut by Monteith, who was Golding’s editor at Faber. What remains is brilliant and all Golding’s own work.

Is Carver a Golding or a T. S. Eliot? That is the fundamental question. We can test the hypothesis by examining Carver’s work before-Lish and after-Lish. Before 1971 and after 1980. A related issue is the nature of the editing. Pound and Monteith cut. On occasion, Lish added and rearranged. He treated Carver’s stories as rough drafts – which is what they were in reality after Lish had redesigned them, a bit like Picasso taking massive liberties with Velázquez’s Las Meninas. Except that Carver was no Velázquez.

One of the things non-musicians find difficult is the attitude of serious composers to tunes. Stravinsky lifts the opening melody of The Rite of Spring