Home Fires Burning E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Georgina Lydia Lee (1869-1965) moved in high society and, together with her husband Charles, had many contacts with members of the Establishment. In October 1913, aged 44, Georgina gave birth to her only child, Harry. Georgina was closely involved with the domestic war. She describes the food shortages that took hold as Britain was blockaded and the terror and carnage caused by the Zepplin air raids that assailed London. Letters from the six serving members of her family alerted her to the despair at the size of the Regular Army in 1914, the reality of the shell shortage scandal in 1915, the shortcomings of Sir Ian Hamilton in the Gallipoli campaign. By late 1916 Georgina shared her countrymen's anti-German feeling, as the scale of the Somme casualties became known. She writes of public figures, such as Sir Edward Grey, Asquith, Churchill and Lloyd George and the events that shook British society in the midst of war. Her diaries offer a fascinating insight into how Britain coped with the pressures and crises of the First World War on the Home Front.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 699

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

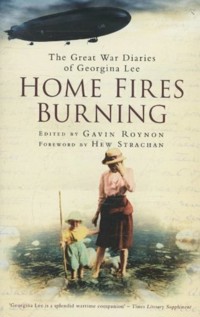

HOME FIRES BURNING

The Great War Diaries of Georgina Lee

HOME FIRES BURNING

GAVIN ROYNON

FOREWORD BY HEW STRACHAN

For Patsy La Meilleure Epouse

First published in 2006

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved © Gavin Roynon, 2006, 2013

The right of Gavin Roynon to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9602 3

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Foreword by Hew Strachan

Acknowledgements

Contemporary Map of Kensington and Chelsea

Not so Remote from the Conflict – Editor’s Note

Map: German Air Raids over London, 1914–18

Family Trees of the Davis and Lee Families

Book I: July 30 – August 29, 1914

Dread in all our hearts – Stock Exchange closed – Belgium’s appeal to the King – ‘we are in for it at last’ – weeping women at Paddington – Army and Navy Stores under siege – hunting down German spies – no standing room in St Paul’s – sewing bed-jackets and pyjamas for the wounded – why Churchill raved like a lunatic – desperate need for recruits – vive le général French! – German goods disappear from shops – no toys at Hamley’s – a walk on Wimbledon Common – Asquith backs Kitchener’s appeal – ‘mutiny’ of Irish Guards – destruction of Louvain.

Book II: August 30 – October 7, 1914

Paris prepares for siege – heroism of Captain Grenfell – Welsh distrust of ‘fighting for the English’ – telegram from Viceroy of India – ‘send a copy to the Kaiser!’ – recruitment meeting in the ‘worst’ county – Dolgelly’s blank record – Smuts brings South Africa into the War – Allied victory on the Marne – Rheims Cathedral – an act of vengeance? – lingering death of Georgina’s father-in-law – Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy torpedoed – the Mayor of Brussels arrested – a widow at eighteen.

Book III: October 9 – December 10, 1914

Fall of Antwerp – DORA and the Lights of London – Captain Williams and HMS Hawke – fire at Glaslyn – a narrow squeak for Grandpa – an extraordinary sight at Aldershot – the German POW camp at Frimley – an unpopular resignation at the Ritz – Prince Louis of Battenberg steps down – Turkey declares war – special wedding licence needed – Charles joins the Veterans Corps – fall of Tsingtao – why Captain Müller of the Emden was given back his sword – death of Georgina’s father at Glaslyn – two Kings meet at Ypres.

Book IV: December 13, 1914 – March 3, 1915

Remember Scarborough! – the last pheasant-shoot at Gelligemlyn – Guy Lee’s Christmas Eve letter – the truth about the Christmas Truce – why the Germans played God Save the King – Charles Romer-Williams takes the Beagles to Belgium – American disapproval of the blockade – Mrs Paget’s dinner party – the Saxons’ ‘truce’ with the Buffs – the truth about the Retreat from Mons – farewell to young Eugene Crombie – Queen’s Hall packed for Hilaire Belloc – Uncle Hugh Lee’s wedding – engineering workers on strike.

Book V: March 4 – May 30, 1915

Food parcels to POWs hi-jacked – lies about England – ammunition in short supply – Lloyd George’s Factory Bill – Kitchener’s appeal to the workers – ‘spend the shells and spare the soldiers’ – the King gives up alcohol – German officers escape – how a Zeppelin helped recruitment – Georgina joins the Chelsea Branch of the Belgian Relief Committee – wounded Tommies at the London Hospital – ‘I’ve had enough of Royal Visits’ – gas respirator crisis – sinking of the Lusitania – anti-German riots – Fisher and Churchill resign – a sad visit to Rustington.

Book VI: June 2 – September 27, 1915

Lloyd George’s plain speaking – ‘our guns are silent’ – the first airman to ‘bag’ a Zeppelin – Guy Lee confirms the shell shortage – ‘everything England does is wrong!’ – Sir John French and the French actress – 300,000 Welsh miners on strike – Mrs Pankhurst leads a women’s march on Bastille Day – emotional departures from Victoria station – ‘these partings are so awful’ – socks knitted by crippled Belgian soldiers – ‘blackest week of the war so far’ – reaction to ‘peace proposals’ – casualty lists from Gallipoli – Zeppelins over Chelsea – recruiting figures fall.

Book VII: September 29, 1915 – February 12, 1916

Food prices escalate – the fate of Colin Dunsmure – change of command in the Dardanelles – Edith Cavell’s courage – King George V’s riding accident – Joffre at Downing Street – Guy Lee summoned by Plumer – sinking of a hospital ship – Uncle Alex’s appendicits – lethal results of faulty grenades – Haig promoted – Christmas at Caerynwch – the Persia torpedoed – Asquith’s Compulsory Service Bill – the ironing room at Mulberry Walk – Queen Mary and the surgical supplies – Capt Guy Lee honoured – Bristol prepares for the Zeppelins.

Book VIII: February 17 – November 28, 1916

Invidious work of the exemption tribunals – Pétain ‘hero of the hour’ – women bus conductors take over – blinded heroes at Anzac Day Service – fate of Sir Roger Casement – Jutland, a Pyrrhic victory? – death of Kitchener – Queen Alexandra’s Rose Day – heroism of the Boy VC – August Bank Holiday cancelled – Haig’s appeal – a feud at the Belgian Surgical Depot – captured submarine on display – gruesome fate of Zeppelin at Cuffley – unloading of hospital trains – Harry Lee’s third birthday – death of Emperor Franz Josef.

Book IX: November 29, 1916 – November 30, 1917

Upheaval in the Cabinet – the German Chancellor springs a surprise – third Christmas of the war – departures from Charing Cross – spiritualism – munitions factory disaster – submarine menace grows – food rationing – problems with removals men – USA enters the war – a droll substitute for Easter eggs – Georgina to be honoured – hospital ships torpedoed – industrial strife – Mrs Paget and the Zeppelin – wartime wedding – air-raid casualties at Chatham – the end of Kerensky – a tonic from Cambrai – the National Anthem on the steps of St Paul’s – Georgina flies her Union Jack – cook joins the WAAC.

Book X: December 2, 1917 – September 9, 1918

Allenby captures Jerusalem – Uncle Baynes dangerously ill – DSO awards for the Lee brothers – direct hit on Odhams Printing Works – rationing bites harder – family wiped out at Royal Hospital – ‘Tank Day’ in Kensington – Easter Sunday in the Great Crisis – Foch promoted – our fourth wartime wedding anniversary – the Zeebrugge Raid – Trenchard’s resignation – de Valera arrested – call-up age extended – petrol pirates caught – Government’s decree on strawberries – King of the Belgians at the Albert Hall – Aunt Edie’s funeral in Bath – ‘did ever brute beasts deserve retribution?’ – Civil War in Russia.

Book XI: September 12, 1918 – November 11, 1919

Shell-shock cases – Lee laid low by ’flu – a sinking outrage – wreath laying in Paris – captured guns in the Mall – naval mutiny at Kiel – ‘I could almost feel sorry for the Germans’ – the Kaiser abdicates – pandemonium in London – Service for the King of the Belgians – Foch and Clemenceau in Piccadilly – ‘we want the Tiger’ – dawn of women’s franchise – Wilson at Buckingham Palace – ’flu ‘killing thousands’ – Harry Lee starts at school – strikes everywhere – Versailles Treaty signed – Peace Day – anniversary of Armistice Day – Two Minutes’ Silence throughout the Empire – the Lee family at the Cenotaph.

Biographical Note on Georgina Lee by Ann de La Grange Sury

Select Bibliography

FOREWORD

In some respects the author of these diaries is not Georgina Lee, but her infant son, Harry, who was nine months old when the First World War broke out. It was to Harry that she addressed what she wrote, and it was thanks to Harry, however unconscious he was of the fact at the time, that they became such a truly outstanding chronicle of the conflict. Maternal love gives her entries the warmth and humanity which engage the reader’s emotions. However, at the same time her determination that, when Harry grew up, he should be able to comprehend the context in which his family’s doings were set, ensures domesticity is cloaked in a wider story. Georgina Lee spent the years between 1914 and 1919 entirely in Britain, and yet she gives today’s reader – like Harry, when he was old enough to read his mother’s journal – a sustained and self-contained account of a global war.

Much of this narrative was clearly pieced together from newspapers. The original diaries include her cuttings, and when in Blair Atholl she expressed her frustration at not being able to get the latest London editions. Thus her commentary often reflects the current journalistic vogue. On 21 May 1915, with Asquith’s Liberal Government in disarray, she condemned Winston Churchill’s impetuosity for Britain’s naval disasters; six months later, without a flicker of irony or apparent self-awareness, she described the former First Sea Lord as ‘one of the ablest men England has ever had’. These internal contradictions confirm that, however polished and well informed her descriptions, she resisted the temptation to revisit them, so leaving inconsistencies in place and ensuring that the account she has bequeathed us is firsthand.

Its quality, its immediacy and its depth of knowledge rebut any suggestion that those who spent the war at home were the dupes of propaganda. Her thirst for information demanded the truth: ‘no good’, she wrote on 20 March 1915, ‘is gained by keeping the country in a fool’s paradise’. From the first she was not buoyed by any false expectations that the war would be short or easy. She embraced the injunction of the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, that the war would last at least three years, and, almost four years later, as the news of the German offensives of March 1918 percolated back to London, her anxiety left her scarcely able to eat. However, Georgina Lee suffered less directly from the war than most women of her age. She had married late in life; her son was – obviously enough – too young to serve, but, as importantly, her husband was too old. Not one of her close relatives was killed, her most immediate experience of bereavement being the death of a young captain in the Gordon Highlanders in 1917.

Until then that officer, Eugene Crombie, had kept her in touch with the realities of the Western Front. So too had her brother-in-law, ‘Uncle Guy’ of the Buffs. It was Guy Lee who told her that the retreat from Mons was a rout and that Saxon soldiers attempting to surrender were shot out of hand. Other correspondents reported with chilling exactness the level of casualties, the nature of wounds inflicted by shellfire, and the quagmire of the trenches. For too long scholars of the First World War allowed themselves to be persuaded by the war novelists of the late 1920s that those at home were swept up by a tide of patriotic rhetoric which opened a gulf in understanding between them and those at the Front. Recent writing has set out to show the opposite – to emphasise how most soldiers longed to return to civilian life, to home and hearth, and that those at home were desperate for information that would help them comprehend the true nature of the fighting. Georgina Lee’s diaries corroborate such interpretations.

Nor was she as exempt from direct attack herself as received wisdom might allow. Her husband’s work as a solicitor kept her in London, worried by the increasing threats of air raids but determined not to have her life dominated by them. Rationality told her that the chances of being hit were small; concern for her son did not permit her to be quite so cavalier. Her household grew. Nationally, domestic service declined in the war as men were called up and women moved to the better-paid munitions industries. But by 1917 the Lees employed twice as many servants as they had in 1914, and nannie, cook and the maids were increasingly opposed to staying in the metropolis. The Smuts Committee, which reported in 1917 on the German raids on London and recommended the creation of an independent air force in response, highlighted the effects of bombing on the morale of the working class in the East End of London. Here class and geography intersected: the East End was closer to Germany and contained the docks and other obvious industrial targets. In the West End, where Georgina lived, class and geography diverged. But the comparative infrequency of bombing did not prevent social stereotypes from asserting themselves.

Georgina herself contributed to the war effort in conformity with her comparative affluence and with an energy and commitment facilitated by Harry’s much-loved nannie. The role of charitable work in the war effort is only just beginning to find its historians, and it is still too early to assess its overall scale. Many of Georgina Lee’s endeavours were devoted to those who were indirect victims of the war, the poor and underprivileged of Britain, as she knitted clothes for the children of soldiers and helped at the Ragged School Union. But Georgina spoke fluent French, her artist father having taken his family to live in Boulogne. As a result she worked particularly with the Belgian refugees who arrived in Britain in the autumn of 1914. Her commitment to hospital visiting, and to preparing hospital clothes and packing bandages, found its focus in the Belgian Red Cross. Her identification with the invaded territories of Belgium and northern France explains her own unswerving commitment to the war and her determination to see it through to victory. Empathy with people whose lives had been shattered by foreign occupation – whether they stayed or fled – fed her own patriotism. Attending a thanksgiving service in Bristol Cathedral nine days after the Armistice was signed, she felt ‘a sudden emotion’ choke her throat. The flags of the Allies ‘are the emblems of so much glory, such heroism and devotion, exultation and final triumph after the agony of four and a quarter years’. Not the least of the achievements of these diaries, their fluency and fullness, is that those feelings bridge the divide of the years.

Hew StrachanChichele Professor of History of War University of Oxford

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It was due to a fortuitous, but most fruitful, conversation at an authors’ lunch that I first met Ann de La Grange Sury and learnt of the existence of her grandmother’s diaries. From the start I was intrigued by Georgina Lee’s original idea of addressing her war diary to her infant son Harry, as though she was putting a message in a bottle and casting it upon the waters, for him to find one day. Where did she find the iron resolve that enabled her to keep up her diary right through the war and beyond, until Armistice Day 1919? As she often wrote at great length – there are eleven volumes – I was compelled sometimes to leave out more of the contents of the diaries than I would have wished.

I am grateful to Ann – who is Harry’s daughter – for entrusting me with this valuable primary source. She has written a detailed biographical note about Georgina Lee and her family, which is printed as an appendix. Ann has also taken a great deal of trouble to construct the Davis and Lee family trees, which will help those readers who are baffled by the diarist’s numerous relations. She has also provided several photographs from her family archives.

Much research has been necessary at the Imperial War Museum: a most enjoyable pursuit, in view of the positive attitude of the team in the Reading Room, who are a model of courtesy and always helpful. In particular, my warm thanks are again due to Roderick Suddaby, Director of the Department of Documents for his helpful advice on editing principles to follow when dealing with those terrible twins, exclusion and inclusion. I am also grateful to Alan Wakefield for helping me to track down some striking photographs of Home Front scenes, from the extensive Imperial War Museum photo-archives. Sir Martin Gilbert kindly gave his permission to reprint his map of German Air Raids over London, 1914–1918, from his Routledge Atlas of the First World War. I am grateful to David Walker and Hazel Cook for enabling me to reprint a detailed contemporary map of Chelsea, which belongs to the Kensington Town Library.

My friend and former colleague Patrick Wilson has again read sections of the diaries, pointed out certain errors and given me some very useful advice. Dr Hugh Cecil kindly helped me with the structure of the book and Malcolm Brown steered me in the right direction when I was drifting towards rocks and shoals in my introduction. Dr Edwin Robertson gave me a vivid first-hand account of his experience as a schoolboy of the Silvertown ammunition dump explosion at West Ham on 19 January 1917. Jon Nuttall, Head of Administration and Curator of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, provided exact details of the casualties and damage to the buildings in Light Horse Court caused by the Zeppelin raid on 16 February 1918. See plate section.

Dominiek Dendooven has dealt with various queries involving the King of the Belgians and the Belgian Army, and Annick Vandenbilcke provided useful information from the Documentation Centre at Ypres, about the Belgian refugees. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright owner of Louis Raemaeker’s cartoons, but so far without success.

Constructing a new book requires input from many different people and so good teamwork is the essence of a first-class publishing house. It has again been a rewarding experience to work with the team at Sutton, whom I cannot commend too highly. In particular I should like to thank Nick Reynolds for his overall supervision and sound advice, also Jonathan Falconer and Julia Fenn for their willing and positive support. I am again very grateful to Clare Jackson for her flexible approach and meticulous attention to detail as project editor and to Bow Watkinson, whose professional scanning skills are second to none.

My wife Patsy devoted much time to reading through the entire text and pinpointed various inconsistencies and ambiguities which I had not noticed. My daughter Tessa also did some helpful proof-reading. Penelope Hatfield, the archivist at Eton College, kindly clarified some confusion about the Dunsmure family. Eric Harrison and Anthony Quick gave me useful information about the Haig Brown family.

Finally, I am again indebted to Janet Easterling, who has presented the text of this book in a highly professional way for the publishers. She has tolerated numerous last-minute amendments and extra footnotes and has still kept to a tight deadline. Without her invaluable contribution, this book might never have seen the light of day.

The Borough of Chelsea in 1902. The Lee family lived here throughout the Great War. Many streets and buildings in this area were bombed. Georgina Lee describes in her diary the devastation and the reactions of Londoners to the frequent air raids. (Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Libraries and Arts Services)

NOT SO REMOTE FROM THE CONFLICT

In one sense, Georgina Lee was fortunate. She benefited from a broad, liberal education and belonged to that social stratum which enjoyed a comfortable Edwardian lifestyle in the – for some – halcyon days before 1914. On the other hand, she married late. Her firstborn and ultimately only child, Harry, was less than a year old when war broke out. Her dilemma was to know whether this precious son would be safe in London. She decided he would not – and packed him off with Nannie to her father’s house, Glaslyn, on the River Wye in Radnorshire.

Georgina then experiences all the pangs of conscience of a mother who has distanced herself from her precious baby. ‘What’s new?’ I hear some harassed young mothers of today asking. But Great Britain is at war, the Germans are sweeping through Belgium and invasion may be imminent. Georgina Lee decides to alleviate her conscience by addressing her diary to baby Harry. She wants him to be familiar one day with the grim events in Europe, but at present ‘You are too small to understand’.

She opens her diary on 30 July 1914, five days before Asquith officially declared war, and launches into the highly personal style which is to be her hallmark. Her warm affection for her son shines throughout – and somehow by ‘speaking’ to him through her diary, she gains some solace for the lengthy periods when she is not with him. Single-minded devotion to Harry lends a striking coherence and unity to the whole and impels her to continue writing her diary for over five years until the first anniversary of the Armistice.

What then is the character of this remarkable lady, who is so committed to her infant son, that she creates a complete war diary for him? She emerges as a warmhearted and compassionate wife and mother, a popular figure with a wide circle of friends, who is more at ease than her husband with all sorts and conditions of men. She is intensely loyal, but sometimes confides her worries about him to her diary. Although they only have the one precious child, both she and Charles have many siblings and belong to large families, whose welfare is never out of her mind for long. Judging by the frequent letters she receives from her brothers and brothers-in-law, she is the hub of the extended family.

There are very few other published sets of Home Front diaries which chronicle the entire war from start to finish. Georgina keeps going throughout and does not limit herself to family concerns. She gives an informed account of the progress of the war at home and abroad and its effect on her life and that of her friends. If it is still claimed that British civilians, unlike those in Belgium and France, were remote from the real conflict, the Georgina Lee Diaries challenge that concept. They provide valuable evidence to the contrary, adding substantially to our understanding of how Londoners reacted to wartime conditions.

At the start, the reader is brought face to face with the panic-stricken days of late July and early August 1914. Even before Great Britain enters the war, Georgina Lee describes the closing of the Stock Exchange and the Bank of England, Paddington paralysed by a rail strike, ‘Church Full’ notices outside St Paul’s, a moratorium on the paying of bills, and chaotic scenes at large department stores. Hoarding of food is rife in London. Among the worst culprits are customers at Harrods, where the store is forced to stop selling goods over the counter. On the east coast an invasion is expected in Harwich any day, trenches are being dug and nobody may leave the town after 6 pm.

In London, an ever-mounting phobia assumes that individuals with Germanic-sounding names are spies. Even the First Sea Lord, Prince Louis of Battenberg, whose connection with the Royal Navy goes back more than forty years, has to stand down. Georgina does not subscribe to this until the gas-bomb scare in 1915. As she had spent her formative years in France and had studied in Germany for two years, she has a European awareness and displays a special sympathy for German-born individuals with British spouses, who are now placed in quasi-POW camps.

In 1915, Georgina witnesses the great women’s march on 17 July. Led by Mrs Pankhurst, 50,000 women processed through London, petitioning for women to be allowed to work in the munitions factories. Georgina watches Lloyd George with an approving eye, as he addresses the demonstration and displayes his skills as an orator: ‘Without women victory will tarry and the victory which tarries means a victory whose footprints are footprints of blood’. The wind of change for women was blowing strongly. Less than three years later, in June 1918, women over the age of 30 were granted the right to vote, provided they were householders or wives of householders.

Georgina becomes involved with several groups helping the war effort, but her greatest challenge comes with her appointment in March 1916 as superintendent of the Belgian Surgical Depot in Kensington. During the last week of June 1916, she responds to a special appeal to provide thousands of shell dressings within three or four days. There is frantic activity when it is realised that a major British offensive is about to be launched: ‘Shell dressings! Words horribly suggestive of the gaping wounds caused by splinters of shell. I worked and worked, never looking up . . . How devastating to be making preparations for the appalling bloodshed we know is to begin in a few days.’

Georgina’s prediction was right. Almost 20,000 British soldiers were killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Such grim statistics were not released to the public until much later. But Paddington, where Georgina saw the hospital trains arrive from the ports, told its own story. The platforms were covered with stretchers and a porter told Charles Lee that, on one day alone, 4,000 wounded had arrived there. The same was true of Charing Cross and Victoria. To see the injured arrive from a few miles across the Channel, maimed and battle-scarred, brought the grim reality of the war very close.

Georgina is appalled by the news of the sinking of the Lusitania and shocked beyond measure by the drowning of Kitchener, the executions of Edith Cavell and of Captain Fryatt, and the torpedoing of hospital ships. But she does not yield to doom and gloom. She witnesses the emotional departure scenes at Victoria and does her best to cheer up those for whom every farewell to son or husband may be their last.

So much attention has been afforded to the Blitz in 1940, that the extent of damage to life and limb from the air in the First World War is often forgotten. One thousand four hundred and thirteen people were killed and 3,408 injured as a result of air-raids.* Of these casualties, more than half were Londoners. East coast towns such as Southend, Margate, Harwich, Ramsgate, Folkestone and Dover were also frequent targets. The motive for these attacks was to render city life intolerable and to destroy morale. Georgina Lee’s diaries show that the Germans succeeded in neither respect.

Initially, Zeppelins had a certain novelty value. A dozen airships cross the coast on an early September night in 1916 and Georgina – rushing outside their Kensington house to see a Zeppelin – reveals her irritation when she is dragged back inside for safety’s sake by her husband and fails to see it. Aeroplane raids presented a greater threat and one of the worst was the first daylight raid on London on 13 June 1917. Seventy-two bombs fell within a radius of a mile from Liverpool Street station, 162 people were killed and 432 injured. These raids continued unremittingly until May 1918, and the Lee family experienced most of them.

Towards the end of 1917, the outlook remained bleak as Georgina began the tenth volume of her diary. The Eastern Front had collapsed and Lenin had withdrawn Russia from the war. ‘Yet another book and the war seems farther from its end than it did three years ago. We have entered a very critical, fierce stage and once again Germany’s position is better, for the time being, than our own.’

Thousands of German troops are transferred from East to West and the great German offensive, so long expected, begins in March 1918. News comes to Georgina via a Grenadier officer that the Germans have exploited a thick fog and are effectively breaking through the Fifth Army. Unbelievably, after the sacrifice of all those lives, the British Army is back on the line of the Somme. Not since the Mons crisis in the early weeks of the war has she felt so worried. Happily, after a few agonising days, the German advance appears to be faltering. ‘Thank God!’ she writes with disarming honesty, ‘I feel inclined to be on my knees all day – so unlike me!’

Nonetheless she heads her diary entry for March 31 Easter Sunday in the Great Crisis. Her husband, Charles, tells her that every available man is off to France. This leaves scarcely a man to mount guard at Buckingham Palace! But Foch is now in supreme command and gradually the tide turns. The Germans are pushed back and in the autumn the proud Habsburg Empire, rent by internal conflict, collapses. Georgina records joyfully how the German government, now isolated, her citizens starving, is forced to bid for an armistice, to avoid revolution.

Far better now for readers to dig into the diary itself and get to the heart of the matter. They will trace the wonderful exhilaration when news of the Armistice comes through. Georgina goes out into the streets of London on 11 November 1918, with her 5-year-old son. She gives an eyewitness account of the elated crowds, the flag-waving, the celebrations and the pandemonium. Yet, for so many, the exhilaration is bittersweet:

Florence Younghusband [one of Georgina’s friends] was on the top of a bus when the guns were fired. In front of her were two soldiers, one with his face horribly scarred. He looked straight ahead and remained stonily silent; the other just bowed his head in his hand and burst out crying. The omnibus conductress dropped into the vacant seat by Florence, leant her head on her shoulder and cried too. ‘I lost my man two months ago, I can’t be happy today,’ she murmured.

Gavin Roynon

* Joseph Morris, The German Air Raids on Great Britain, 1914–1918, Preface, p. v.

The Families of LEE and ROMER-LEE

Notes (relating to the Lee Family Tree)

1. Minna Constance Williams is affectionately referred to as Muz by Georgina Lee throughout her diaries. Minna was the daughter of Charles Reynolds Williams of Dolmelynllyn, Dolgelly.

2. Harry Lee assumed the surname Romer-Lee in later life and his descendants have maintained this as their family name. Georgina Lee refers to him either as Uncle Harry or Uncle Tich (his nickname, because he was so tall).

3. Brenda Wason was the daughter of Rt Hon. Eugene Wason, who was MP for Clackmannan and Kinross when war broke out in 1914.

4. Ella Sale-Hill was the daughter of Gen Sir Rowley Sale-Hill, KCB.

The Descendants of Henry William Banks Davis RAand Georgina Harriet Lightfoot

Notes (relating to the Davis Family Tree)

1. Henry William Banks Davis RA lived from 1862 to 1901 with his family at Le Château de la Barrière Rouge, St Etienne au Mont, near Boulogne. It was here that Georgina Lee and her siblings were born. Today this handsome country house, which dates back to the Second Empire, is occupied by the Huguet family and known as Les Quesnelets.

2. The mother of the diarist, Georgina Harriet Davis, died in 1879. She was buried in the graveyard of Rhayader 35 years later. See diary entries for the first week of December 1914.

3. Henry John Davis adopted the surname Banks-Davis, but was the only one of his siblings to do so.

4. After the marriage of Arthur Davis to Audrey Clive, the couple adopted the surname Clive-Davies.

5. Philip Osorio changed his surname by deed poll to Probert.

6. Both Dunsmure brothers served in the Cameron Highlanders. They were killed within a few months of each other. 2/Lt Colin Dunsmure was 21 only a few days before he left England. He was last seen alive at Loos on 25 September 1915, when his devoted servant H.P. Thompson tried to carry him into shelter, but was killed doing so. See diary entry for 12 October 1915 – when conflicting telegrams were reaching his Mother – and for 5 January 1916.

1914

What had the Belgians done, that their country should be invaded and ravaged?

Sir Edward Grey

BOOK I

JULY 30 – AUGUST 29, 1914

THURSDAY JULY 30

15 Neville Street, South Kensington

You are nine months old, my little son, when I begin this Diary. We are parted at present, at what cost to the joy of the house, only your Father and I know. You are too small to understand. You are happy as the day is long at Glaslyn* with a Grandfather who adores you while Daddy and I remain alone in London. Your Grandfather’s message today says ‘Baby is a real little Hercules – He seems to think I am there on purpose to joke and laugh with. As soon as I appear he entices me to play.’ Your Nannie, a quiet, placid Somersetshire woman, who sings to you all day, writes ‘The mountain air is doing Baby so much good that his cheeks are as firm and rosy as apples.’

But there is one solemn reason that makes me start my Diary tonight. Grave rumours of a possible terrible conflict of Nations are on everybody’s lips, and have been gathering for some days past. If indeed the dread that is in all our hearts is justified by future events, my little boy will have some idea of what War means to our Country. Except for the Boer War, thousands of miles away, we have been at peace with our neighbours for one hundred years. If we fight, it is because we shall have been dragged in through loyalty to our friends abroad.

Sir Edward Grey, the Minister for Foreign Affairs whose name will go down as one of the most patient Peacemakers the world has known, is failing to reconcile the quarrel between Serbia and Austria, with Germany, lusting for War, at her back to make peace impossible.

The murder of the Crown Prince (and his Consort) of Austria by Serbians is the excuse for provoking war. If Austria declares war on Serbia, Russia must help Serbia as they are all brother Slavs together. Germany is Austria’s ally, and France must help Russia if attacked – we are France’s friends, and cannot allow her to be crushed.

Therefore, my baby, whose dimpled hands, however eager, cannot yet grasp a weapon for the honour of your country, we must wait and see what the next fateful days bring forth.

FRIDAY JULY 31

This being Bank Holiday weekend, Daddy and I had arranged to spend it at Cossington.* We were to start from Paddington at twelve. But at breakfast, we saw in the papers that Germany has flung down the gauntlet. She is taking as a pretext the preparations for war Russia is making on the Austrian frontier. Worse still, breaking all conventions, she is marching to invade the neutral state of Luxemburg. This is an open menace to France.

There is such a panic on all the money markets on the Continent, that to protect itself our Stock Exchange has closed for an indefinite period. Bad as this is, it saves the country from a worse catastrophe, for it prevents foreign securities from being dumped on our market, it saves a panic rush on our banks, and chaos. But it causes the sudden ruin of many stockbrokers,** and a feeling of terrible depression throughout the country.

One has heard of well-known City firms being ‘hammered’ the last two days, but now all the offices are closed, and behind the closed door each firm is reckoning its losses. I heard something of it as I sat for an hour at Paddington waiting for our train. A sense of impending calamity hanging over everyone, overcame the ordinary reserves of English people. Tongues were loosened, people spoke of their experiences.

An elderly man sitting by me in the waiting room told me in listless tones he had been on the Stock Exchange forty years, and had never known it close in a crisis, nor seen so many failures in a few hours. The room was crowded with holiday people and children making the best of the absence of the trains which should be taking them to the seaside. They played with their spades and pails on the dusty floor of the waiting room.

To add to the general disorganisation, the shunters of the Great Western had seen fit to go on strike a few hours earlier. Paddington was getting every moment more congested by would-be travellers finding the platforms packed by people who should have departed some hours previously.

We wired to Aunt Ethel that there was a strike at Paddington and we did not know when we could arrive. We finally did board a train, that took us straight to Taunton, twenty-five miles beyond our destination, but that was a trifle, since we reached Aunt Ethel at 8 o’clock instead of 5.

Your cousin, wee Patience, rushed into the hall and suspended herself by both arms from my neck. Patience is five, a little fairy with large grey-green eyes and long dark lashes. With her tiny fingers she models the most astonishing little objects out of plasticine, nothing too minute, even a string of monkeys climbing up a tree, the whole thing not more than 2 inches high. She is the cleverest little girl I know.

SATURDAY AUGUST 1

The papers at breakfast announce the official declaration of war on Russia by Germany, and so, my son, the Emperor, or Kaiser, Wilhelm II, has thrown off at last the mask of peacemaker he has worn for ten years and shown himself in his real light. There was no reason for Germany to meddle in Austria’s quarrels with her vassals. The Kaiser has long thirsted for an opportunity to hurl his gigantic army and his fleet, at the whole of Europe.

For the last ten years our country has looked with suspicion at the continually expanding German Fleet. Yet friendly relations have increased between the two countries. Until just lately the German papers were congratulating themselves that the two peoples had at last reached a good understanding. Now that the German Army is invading Luxemburg, these illusions are fast vanishing. Yet we must be patient, and not jump at once to the worst view.

To revert to more peaceful topics. We spent the day at Cossington walking about the neighbourhood which is very picturesque, but so busy were we, discussing the chances of war in all its aspects that we scarcely noticed the scenery.

Uncle Baynes* was chiefly concerned as to whether England would join in. The mere possibility that she might not, filled him with disgust. With our Navy at the very height of its strength and efficiency, and our aeroplanes ready to do such splendid service, it would be a mighty pity if we did not have a go at the Germans. Uncle Baynes’ views are I think, shared by the majority.

SUNDAY AUGUST 2

No newspapers to be had today in Cossington, but as we intend to motor to Taunton this afternoon, we may get them on the way home. Taunton, my baby, and its neighbourhood was the home of some of your ancestors. Your great-grandmother was a Corfield, and many are the tales she told us when we were children, of the home of her girlhood in sunny Somerset.

Having delved into the peaceful recollections of a century ago, we remembered the great excitement of the war, and made for a newspaper shop in Taunton. Imagine our shock of surprised excitement on reading that Germany has invaded French territory without even declaring war and while the German Ambassador is still in Paris! So far there has been no collision, but Germany’s brutal threat to ‘blot France out from the map of Europe’ shall not be realised, please God, as long as England is there to help.

MONDAY AUGUST 3

Today has been very wet. Heavy showers pouring on the little garden enclosed by high walls, make it a gloomy abode in bad weather. Most of the day we have sat in the sheltered loggia, discussing Belgium’s appeal to King George to help her against Germany’s brutal invasion.

In 1839, Germany had pledged herself, with other Powers, to respect the neutrality of Belgium. Yet an attack on France through Belgium is her avowed plan of campaign. Having reckoned on the compliance of Belgium, she has insolently threatened her if she attempts to resist; if however she submits to the desecration of her territory, Germany promises to leave her intact when peace is signed.

To this ‘infamous proposal’, as Asquith stigmatised it in his great speech in the House, the King of the Belgians gave an indignant refusal.* Having appealed to King George to stand by him, he prepared for a vigorous defence at Liège.

Sir Edward Grey also delivered a great speech, laying before the house his attempts to secure peace, and declaring that ‘England cannot stand aside if France is to be attacked’. He explained how Germany had appealed to England not to interfere, promising that if our Navy leaves Germany alone, Germany claims she will not interfere with French territory along the coast!

TUESDAY AUGUST 4

We had to leave Cossington very early, at 7.30, to get back to town by midday for Daddy to be at Westminster. The Archbishop and the Bishop of London did not leave London, owing to the crisis, and their presence means much more work for their Legal Secretaries.**

The thrilling news we found at the station was that Sir Edward Grey, has delivered an ultimatum to Germany, ‘If by midnight tonight Germany has not pledged herself to respect the neutrality of Belgium, England will declare war’ – meantime the British Army has begun mobilising. Of this we had ample evidence on our journey up. Already trains full of soldiers were at every station. When we reached London soldiers and officers in khaki were everywhere.

Daddy came home from the Sanctuary in the evening saying there was no cash to be had anywhere; not even at his club could they change a £5 cheque. The Banks are to remain closed until Friday, and the Government has ordered a ‘moratorium’. This means no debts can be recovered by law until a date is fixed. The tradespeople have not sent in their weekly books.

Your Uncle Gerry came to dine with us.* He is on the Stock Exchange and, as he explained to us quite cheerfully, is ruined for the time being. His kindness and liberal generosity to those in need of help, are untold. His only fault is an excess in this direction. This puts himself at present in a tight corner, when he should have ample resources. He left us at 11 pm to go to his club, White’s, to await the news of Germany’s decision.

Awakened soon after midnight by shouting in the street. We guessed that war was declared and were a long time going off to sleep again after that!

WEDNESDAY AUGUST 5

We are in for it at last. But there is not one of us in the country who is not thankful at heart that the great fight is to take place at last. The strain has been too great for many years. We all marvel at the reckless audacity of the Kaiser who, with Austria, has Russia, France, England and Belgium to fight. Italy has declared she will remain neutral.

This has been a day of emotion and new experiences. Having promised to see Uncle Gerry off at Paddington in the morning, I started with him in a taxi. The first unusual sight we met with was at the Powder Magazine in Hyde Park. Our taxi was held up by the manoeuvres of a whole fleet of motor buses, in the hands of soldiers, who were bringing out cases of ammunition and removing them. All was quiet at Paddington, though the railways are taken over by the State from today, for the transport of troops.

We were surprised to see the platforms filled with poorly-dressed men whom we took for unemployed come there to make a disturbance. But after the departure of our train we saw our error and made mental reparation for hard thoughts. Numbers of weeping women began to file down towards the exits, accompanied some by a small son or an old man trying to console them. For the first time I realise what these scenes mean that are going on round London in every station and all day. All reservists are being called up.

Uncle Gerry was loth to leave London during these stirring days, but he is badly needed at Gelligemlyn** where your darling Gran is very, very ill. It is one of Mummy’s greatest griefs that you will never know your Daddy’s Father, a man beloved by all who know him, rich and poor. For 3 months now he has been hopelessly ill, and all we can do is to stand by and give him all the affection in our hearts.

Later in the day, I had to go to the Army and Navy Stores to get in provisions. But what a state of affairs I found! The grocery and provisions departments had been under siege all day, from customers anticipating a sudden shortage of supplies.

All the men behind the counters were absent. Only a few foremen walked about, displaying a patience worthy of the Order of Merit. But nothing was sold over the counters. Long tables were littered with order forms and pencils, and here everybody had to write out his own order with no guarantee as to delivery or prices. Articles will be charged at the price current on day of despatch, perhaps a fortnight hence. They had had 7,000 orders for groceries that day and were overwhelmed.

People have lost their heads, and are all seeking to hoard food. This is a fatal mistake, as it creates a famine. Also an enormous rise in prices, which is most unfair for the rest of the community. I hear of one woman who ordered £500 worth of groceries at Harrods, and another who actually bought over the counter £45 worth. Her chauffeur stood by, carrying off parcels in relays to her motor car.

On coming in at 7 pm I could have cried with vexation. Your Aunt Edie, who has been staying at Sheringham on the East Coast, telephoned from Paddington to say she was there with little Winnie (6) and Geoffrey (2½) with Uncle Lionel and Nurse. She had wired me to meet her, and wondered why I hadn’t turned up. She hoped to reach Bristol some time tonight.

Now this is terrible. The railways are dislocated, their house at Clifton is closed, with no servants and no food in it. I had written to Aunt Edie to tell her I would put them all up here. But she never received my letter, because of the disruption of postal arrangements. It seems to me inconceivable, though, that her hostess should have allowed her to travel on the first day of the war and go right across the country with two little mites!

At 10.30 tonight another wire, this time from your Uncle Romer, your Godfather, asking us to put him up tomorrow, as he has his orders. We are to get him a sleeping valise and cork mattress at Harrods.

I am very, very tired tonight, and yet my brain is so excited, I don’t think I shall sleep much. Lord Kitchener has been made Secretary of State for War.

THURSDAY AUGUST 6

There isn’t a sleeping valise to be had in all London. This is the result of our efforts, begun at 9.30 am at Harrods, to buy one for Uncle Romer. The Camp Equipment Department at the Army and Navy Stores was besieged by officers and relatives trying, like Daddy and me, to procure campaigning requisites. However, we did secure a cork mattress. We made a dash for one and Daddy shouldered it for fear of losing it. He and I then marched back with it to his office. Nobody minds what he does these days.

The forts round the city of Liège are so invulnerable that the enemy cannot get through. The Belgians are suddenly the heroes of the hour, for their splendid stand is playing havoc with the German plan of campaign. This serious check is giving time to England to send her army across to join the French and Belgian forces.

The general indignation against Germany is bearing dangerous fruit. All the nations are turning against her and towards England who is championing the cause of a small people and a great ally threatened with disaster. The Americans are vehement in their praise of England and abhorrence of the German ‘mailed fist’. Japan has offered her navy’s services, and all the colonies are offering assistance.

At sea, several German reverses are reported. The great Hamburg-Amerika liner Königin Luise was sunk yesterday by a light cruiser, the Amphion, while laying mines in the Channel.*

Sir Edward Grey is the most popular man in England today. We feel proud of this statesman who has steered the country so honourably through the biggest crisis in our history. I am reminded of the prophecy of our German Governess when my sisters and I were children. ‘The German Empire will fall under the reign of an Emperor with only one arm and who mounts his horse from the wrong side.’ The German Kaiser has a withered arm, and mounts from the wrong side.

Your Uncle Romer arrived at 9 at night. He is on the Headquarters’ Staff of the Mounted Division, Central Army of Home Defence, and will be at Bury St Edmunds for the present. His staff appointment pleases us all.**

FRIDAY AUGUST 7

Every hour makes the situation more thrilling. Astounding developments occur. I grudge every moment spent indoors, out of sight of the fresh crops of news posters that spring up continually. London seems to be all turned into streets, which are seething with human beings. We had a good experience of this driving right across the city to Liverpool Street Station with Uncle Romer, in full uniform and accompanied by baggage and kit, to see him off to Bury.

The taxi crawled from the moment we reached the Law Courts. There seemed to be thousands of men in cabs. As we moved slowly forward our footboard was boarded every minute by newsboys thrusting special editions in our faces. Your Uncle Romer who to his splendid physique and lion’s heart adds the calmest disposition possible, only smiled at the invasions, and thanked them every time in the same polite way.

But your Daddy, I’m afraid, is not so gentle. These continual noisy interruptions got on his nerves. In his already strained state, he spoke so sharply and looked so fierce, that from that moment we were left alone. The crush at Liverpool Street was terrible. Numbers of natives, too, were returning to India from that station as well as soldiers to the East Coast.

But through the pandemonium our big handsome Staff Officer remained serene and composed, distributing smiles all round even to the porters. He pulled a little aluminium cigarette case from his pocket, given him by Uncle Gerry years ago, and said he had left all his valuables behind. When the train moved off I had such a lump in my throat that I couldn’t say goodbye.

Driving home, we saw the Bank of England open for the first time since the 3rd, and queues of people were streaming in quietly to cash their notes.

On coming home at 7 o’clock with Daddy whom I had been to fetch at Westminster, I found a wire from Uncle Romer. He must come back tonight as he has been summoned by his General to a meeting. He arrived at 9.30 pm. Then another wire came from Aunt Clara saying she was also coming to us for the night to see Uncle Romer. So we set to, and made up the bed in your second nursery.

At midnight she arrived overjoyed to find Uncle Romer, as she hardly expected him to arrive till next morning. She was in a frantic state, fearing the summons back to London meant Uncle Romer was to be sent at once to Belgium, so she was determined to see him once more. They sat talking together upstairs until the early hours.

SATURDAY AUGUST 8

Uncle Romer went to his Staff meeting and came back to 2 o’clock lunch. The fare I provided was simple but sufficient for wartime, roast beef and plum tart, as we are told to use the utmost economy in our food. The Bishop of London in a sermon a few days later said nobody, however rich, should have more than two courses for dinner.

After tea Daddy and I went for a walk to see what was going on. Went to Wellington Barracks where the troops are mobilising fast. A long row of horses of all sorts, cart and carriage horses, hacks and hunters, were picketed behind the railings, munching happily at bundles of hay laid out before them. Soldiers were walking up and down with relatives come to say goodbye. Transport wagons were being packed and tarpaulins dragged on the top of those ready to depart.

While we watched, a detachment of men with bayonets fixed and in full campaign order marched out of the gates past where we stood in a big crowd and disappeared in the direction of Waterloo. We then saw two motor cars in which sat two officers of the Flying Corps just ready to go off. A third officer, with a cheery resolute air came out from the gates with an elderly lady and pretty girl speaking very fast. Laughing he caught hold of the girl, kissed her, and jumped into the car which drove quickly away. The poor girl watched the car out of sight with a look of perfect misery.

Today serious measures are being taken to hunt out German spies. All Germans still in England have to report themselves to the police. Several successful raids have been made on suspicious houses and any arms or ammunition was removed by the police.

SUNDAY AUGUST 9

Official news of the seizure of Togoland, Germany’s colony in West Africa since 1884. It was their first colony and now seems destined to be incorporated into our Gold Coast. It was seized at once because it possesses the most extensive wireless station outside Europe.

Daddy and I went at noon to see the 2nd Grenadier Guards march past Buckingham Palace on their way to who knows where? The Prince of Wales has been attached to the 1st Battalion. The Prince, with the King, Queen, Princess Mary and Queen Alexandra, were in the courtyard before the Palace, watching the march past.

The crowds outside must have numbered five or six thousand. A great column of these splendid fellows filed past to the strains of The British Grenadiers. Everyone was too affected, I think, to cheer. It was a very stirring sight, but we are getting used now to seeing our regiments go by. Every day we have them trooping down the Fulham Road at the end of our street, bands and pipes playing and followed by a crowd. All the board schools are turned into barracks for the Territorials.

This morning I saw the school in Draycott Avenue besieged by eager little boys climbing up the gates to stare at the soldiers who have taken possession of the class rooms. They were seen leaning on the window sills smoking a peaceful cigarette while they have the chance.

This evening we had hoped to hear the Bishop of London’s sermon in St Paul’s Cathedral, before he himself goes into camp with the London Rifle Brigade of which he is Chaplain. We had the greatest difficulty in getting on to an omnibus at all. They were all packed inside and out, and when at last we reached Ludgate Hill, we could see the approaches to the Cathedral blocked with people, and large ‘Church Full’ notices.

It was very disappointing for the Service must have been most impressive, with our Army just on the point of embarking for the Front. We turned away and went to St Bartholomew the Great, the oldest church in the City, and attended the Service of Intercession.

It was a beautiful night, and the crowds filling the City and the precincts of Westminster and the Palace were as great as on Coronation Day.

MONDAY AUGUST 10

The newsboys’ shouts seem to have stopped. War news is scanty. With Lord Kitchener at the head of military affairs this is only to be expected. All information as to movements of our Army and Navy is kept out of the papers. Kitchener has appealed to the country for a second army of 100,000 regulars.

The London streets are quietening down, soldiers are much scarcer and seem to be vanishing silently. Food prices are practically normal. 2,000 motorbuses,* with their drivers who are reservists, have gone from London to Belgium to transport soldiers to the Front.

TUESDAY AUGUST 11

The town is growing very quiet. But under this calm exterior the public are bracing themselves to face the terrible events we must expect. Everywhere people are organising relief, and making arrangements for temporary hospitals. The Red Cross Headquarters are at Devonshire House. Every district is establishing Committees to work under the direction of the Headquarters Staff, so that no efforts are wasted by working in an inexperienced and useless way.

This morning being the day on which I pay my weekly bills, I went round to the tradesmen who had not sent in the books for a fortnight and asked them to do so at once. They seemed so surprised, but Daddy has just explained that the ‘moratorium’ ordered by the Government, during which no debts need be paid, still holds good till September 4th. No Bank need cash a cheque over £5, unless it be for wages. Wages are the only legal debt that need be paid.

Paper money is now everywhere in use. £1 notes and postal orders for which no commission is charged, are legal tender.

WEDNESDAY AUGUST 12

Grouse Day! The very best grouse moor in Scotland can be rented today for £5, they say. There is scarcely a sportsman left on the moors, yet the few who are too old to join the ranks and still hale enough to tramp the moors are enjoined to shoot, if only to send the proceeds to the national funds. The Prince of Wales Fund amounted last night to £500,000.

This morning a notice was brought to me by two ladies on behalf of the Kensington Detachment of the Red Cross Society. The Borough has undertaken to equip hospitals for 200 beds, by voluntary contribution. A long list of furniture, utensils, bedding and other requisites was given to me, with a request to mark down those things we would undertake to provide. I must then mark each article and pack them ready to be called for at a moment’s notice. I shall give sheets, pillowcases and towels, the folding chairs we use on the balcony, some jugs and a few other items.

Uncle Alex has asked us to put him up for two nights and insisted on paying for his board in these hard times.* I was going to refuse, but shall now accept a donation to produce more articles for the Kensington Hospital.