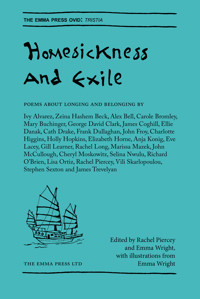

Homesickness and Exile E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Emma Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: The Emma Press Ovid

- Sprache: Englisch

How does it feel to be a foreigner? Can you choose where you call home? What if you reject your home or your home rejects you? Homesickness and Exile is a fascinating collection of poems about the fundamental human need to belong to a place, as poets from across the world provide profound and moving insights into the emotional pull of countries and cities. Poems about homecoming, departure and both voluntary and involuntary exile provoke reflections on alienation and identity, and a recurring theme is the yearning for a sense of belonging and acceptance by a place. This anthology is inspired by the Tristia, a collection of poems written by the Roman poet Ovid after he was banished from Rome by the Emperor for an unknown misdemeanour. Homesickness and Exile expands on Ovid's themes and considers spiritual as well as physical exile in the modern world, with poets writing about rootlessness and geographical ennui.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 56

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Homesickness and Exile

Edited by Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright

With poems from Ivy Alvarez, Zeina Hashem Beck, Alex Bell, Carole Bromley, Mary Buchinger, George David Clark, James Coghill, Ellie Danak, Cath Drake, Frank Dullaghan, John Froy, Charlotte Higgins, Holly Hopkins, Elizabeth Horne, Anja Konig, Eve Lacey, Gill Learner, Rachel Long, Marissa Mazek, John McCullough, Cheryl Moskowitz, Selina Nwulu, Richard O’Brien, Lisa Ortiz, Rachel Piercey, Stephen Sexton, Vili Skarlopoulou and James Trevelyan.

A Guide to Using This Ebook

When I started the Emma Press, I wanted to create the kinds of books which people wanted to carry with them, to read on busy commutes and on holiday. Homesickness and Exile is especially appropriate for this, so thank you for buying this ebook.

The difficulty of formatting poetry ebooks

Some of the poems in this book have experimental layouts, with multiple levels of indentation and gaps between words on lines. This is difficult to recreate in an ebook, because the ebook can be read on so many different devices which each treat formatting slightly differently.

My solution

I want to create reflowable ebooks instead of fixed-format ebooks, which only really work on large tablet devices like iPads. So, to make this reflowable ebook work, I’ve done my best with the formatting on difficult poems but also included a screencap of how the poem looks on the printed page. This means that you can still adjust the size of the text, but you can also see how the poet intended the poem to be read.

— Emma Wright, 21/9/14

Copyright

First published in Great Britain in 2014

by the Emma Press Ltd

Poems copyright © individual copyright holders 2014

Selection copyright © Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright 2014

Illustrations and introduction copyright © Emma Wright 2014

All rights reserved.

The right of Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright

to be identified as the editors of this work

has been asserted by them in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988.

eISBN 978-1-910139-10-3

Print ISBN 978-1-910139-02-8

A CIP catalogue record of this book

is available from the British Library.

theemmapress.com

Contents

A Guide to Using this Ebook

Copyright

Preface, by Emma Wright

Light on the Galactic Tide, by Anja Konig

Dundalk, by Frank Dullaghan

Homecoming, by Selina Nwulu

Yellow Sea Night, by James Trevelyan

Emigrant, by Carole Bromley

Foreign, by Mary Buchinger

Ithaca, NY, by Anja Konig

Prodigalia, by George David Clark

One Morning, Borås, by James Coghill

Paris, Texas, by Alex Bell

Coming down, by Elizabeth Horne

Mzungu, by Cheryl Moskowitz

Away, by Carole Bromley

Exile, by Charlotte Higgins

Women of Corinth, by Eve Lacey

Aunty, by Rachel Long

Hiding from a Mouse, by Holly Hopkins

On Rosebery Avenue, by Rachel Piercey

Coming Home, by Ellie Danak

The Town, by Alex Bell

Ariel, by Charlotte Higgins

What Greta Garbo Offered, by Ivy Alvarez

The Restaurant at One Thousand Feet, by John McCullough

Winged Carrots, by Zeina Hashem Beck

The boy travels, by Elizabeth Horne

The Terminal Building, by Carole Bromley

Leaving Perth, October 2012, by Cath Drake

Samovar, by Marissa Mazek

Interview Conducted through the Man-Eater’s Throat, by George David Clark

Forgetting How to Swim, by Richard O’Brien

In a local café, by Vili Skarlopoulou

Skype, by Stephen Sexton

England, where did you go?, by Holly Hopkins

The Descent from Mount Olympus, by Gill Learner

Before, by Selina Nwulu

Common Prayer, by John Froy

Back Home, by Rachel Long

vena cava, by Ivy Alvarez

Ten years later in a different bar, by Zeina Hashem Beck

Marooned, by Lisa Ortiz

Acknowledgments

About the poets

Also from the Emma Press

* * *

List of illustrations

I.1. Ovid sends a book of sad poems back to Rome.

I.2 Ovid recalls his voyage over stormy seas to Tomis.

I.3 Ovid struggling to leave on his last night in Rome.

I.4. Ovid’s ship is in danger of being blown off course.

I.5. As he endures the storm, Ovid misses his loyal friend.

I.6. Ovid praises his beloved wife.

I.7. Ovid wishes to be remembered for the Metamorphoses.

I.8. Ovid’s fresh fury for a treacherous friend.

I.9. Ovid remembers a friend who did stand by him.

I.10. Ovid describes his ship’s journey to Tomis.

Preface

Part of the appeal in reading the Classics is seeing what still resonates today. Feeling something in response to words written in a completely different culture over two thousand years ago creates a connection across the millennia and raises fascinating, sometimes disturbing, questions about what it means to be human.

When the Roman poet Ovid was ejected from Rome by the emperor Augustus and sent to Tomis, a remote town on the Black Sea, he wrote five books of poetry in an attempt to bring about his pardon. These books, the Tristia, describe his last night in Rome, his terrifying journey across stormy seas, his misery in Tomis, his abandoned wife and friends, his early life and poetic works, and – above all – his hope that Augustus will relent and let him come back to Rome.

Ovid’s heartbroken descriptions of his wife and friends will resonate with anyone who has ever had to leave behind a loved one, but for me the fascination lies in Ovid’s unwavering belief in where his home is. He’s been banished from it by Augustus and he’ll live the rest of his days in Tomis, but his home will always be in Rome – not where he was born, but where he chose to live, surrounded by his wife, friends, library, reputation and personal history. In a very callous way, I feel envious of Ovid in his absolute conviction in where he calls home, because it strikes me as quite rare and wonderful to be able to identify somewhere as your home with full satisfaction and accuracy. Ovid may have lost it, but he had it to begin with: somewhere he was happy to belong.

When we launched the call for poems for this book, I wondered what we would learn about modern attitudes to home and whether Ovid’s feeling of bereavement would be echoed in any of the poems. In the privileged world of cheap flights and Skype, people can, in theory, go wherever they like, come back and visit often, and stay in touch via the Internet. Do people even feel homesick like Ovid anymore?

In the poems we collected, the concept of ‘home’ appears to be problematic, at once more flexible and more elusive than it is for Ovid. In Holly Hopkins’s ‘