1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 0,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

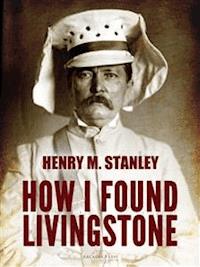

In "How I Found Livingstone," Henry M. Stanley chronicles his daring expedition to locate the famous missionary and explorer, Dr. David Livingstone, who had lost contact with the outside world in Africa. Written in a vivid and engaging prose style, the narrative serves as both an adventure tale and a compelling exploration of the complexities of African geography and culture during the 19th century. Stanley's keen observations and detailed accounts of his encounters with native tribes reflect the broader themes of imperialism and exploration that characterized the Victorian era, offering readers a glimpse into the intricacies of the continent at that time. Henry M. Stanley, born in Wales in 1841, became known for his adventurous spirit and relentless pursuit of discovery, which were essential catalysts for this book. His background as a journalist provided him with the skills to document his journey effectively, while his earlier experiences in the American Civil War shaped his resilience and determination. Stanley's desire to uncover the mysteries of Africa, coupled with a personal fascination with Livingstone's mission, drove him to undertake this perilous journey, leading to a pivotal moment in both his life and the history of exploration. This remarkable narrative is a must-read for anyone interested in the era of exploration, imperialism, and adventure. Stanley's vibrant storytelling, combined with the historical significance of his journey, makes "How I Found Livingstone" an essential work that not only informs but also entertains. It illuminates the spirit of exploration while providing a thoughtful reflection on the ethical dimensions of Western encounters with Africa. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - An Author Biography reveals milestones in the author's life, illuminating the personal insights behind the text. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

How I Found Livingstone

Table of Contents

Introduction

A lone journalist threads a path through uncertainty to meet a legend no one can find. From this stark premise emerges a narrative that fuses grit with curiosity, charting a journey through rumor, geography, and the limits of mid-nineteenth-century knowledge. The drama does not rely on spectacle alone; it is the cadence of pursuit, the steady accumulation of facts, and the human urgency of a search that gives the book its enduring pulse. Henry M. Stanley writes not merely to arrive, but to show how arrival is made possible—by decision, by endurance, and by the irreducible mystery that draws one person toward another.

This work is considered a classic because it shaped how adventure could be written without surrendering the exactitude of reportage. In an era when global news was beginning to move as quickly as steam and telegraph allowed, the book proved that disciplined observation could also carry narrative electricity. It bridged the period’s fascination with discovery and the literary appetite for character-driven travel. Its influence persists in the way later authors combine on-the-ground detail with a storyline of pursuit. The book solidified the notion that a journalist could be both witness and protagonist, a figure whose credibility and charisma propel the tale.

Its classic status also rests on the balance it strikes between immediacy and retrospect. Stanley’s pages are crowded with distances, dates, bargaining, illness, and weather—yet the story arcs toward a moral and intellectual encounter that readers sense long before any meeting occurs. The book’s composure under stress became a model for travel writing that values accuracy over bravado while still delivering tension. It helped codify an adventure template: uncertainty framed by maps, scarcity managed by planning, and purpose clarified by a single human objective. Many later narratives of exploration and reportage echo this measured, purposeful momentum.

Key facts anchor the story. How I Found Livingstone is by Henry M. Stanley and was published in 1872, soon after the expedition it recounts. The author, working as a special correspondent for an American newspaper, undertook a mission to ascertain the fate and location of Dr. David Livingstone, a Scottish missionary and explorer whose whereabouts had grown uncertain. The book describes the organization of a caravan on the East African coast, the progress inland over many months, and the steady conversion of rumor into verifiable knowledge. It is a first-person account that blends field notes with a coherent narrative of pursuit.

Readers encounter a carefully assembled journey: porters hired, guides consulted, supplies counted and recounted, and routes chosen through forests, plains, and lake-dotted interiors. Stanley records the practicalities of movement—how food is obtained, how discipline is maintained, how information circulates along trade routes—as conscientiously as he records the landscapes themselves. The geography points toward a great inland lake and the settlements around it, but the book’s interest is less in cartographic novelty than in the logistics of reaching any coherent truth about a man and a place. The caravan becomes both engine and metaphor of the search.

Stanley’s stated aim is to report faithfully to readers who could not travel with him, to chart the steps by which uncertainty yields to fact. He writes with the urgency of a correspondent and the patience of a traveler, documenting hardships not to sensationalize them but to explain the cost of verification. The book intends to honor the intellectual and humanitarian stature of the figure he seeks while also demonstrating what sustained inquiry demands in hostile conditions. Without offering revelations beyond its premise, it makes clear that the enterprise is as much about method as it is about destination.

Stylistically, the narrative adopts an unadorned, observational voice punctuated by moments of awe. Measurements, times, and numbers accumulate, giving precision to a landscape that contemporary readers knew mostly as outline and rumor. Scenes of negotiation, medical care, and provisioning reveal a granular understanding of caravan life. Yet the reportorial cadence does not preclude reflection; a sense of moral responsibility repeatedly surfaces, especially when choices affect lives and livelihoods. The book’s structure—episodic but forward-driving—mirrors the march itself. Each stage brings new obstacles to register, weigh, and overcome, so that the reader feels both the burden and the momentum of progress.

Historically, the book emerges from a contested moment. Nineteenth-century East Africa was shaped by intersecting missionary efforts, trading networks, and imperial ambitions, along with the brutal realities of enslavement and regional conflict. Stanley’s account reflects the assumptions and vocabulary of his time, and modern readers will recognize biases that require scrutiny. Yet precisely because it records the outlook of a particular era, the narrative is a valuable document for understanding how information was gathered, framed, and circulated. It invites critical engagement with the ethics of description, the power relations of travel, and the responsibilities of those who write about others.

At its thematic core lies the tension between rumor and proof, absence and encounter. The search for one person becomes a meditation on what it means to know, to verify, and to be accountable for the words that claim knowledge. Perseverance is everywhere: in steps counted against fever, in journals kept against fatigue, in maps corrected as terrain refuses easy comprehension. Leadership, too, is tested—not only in command but in care. The book asks how resolve is sustained without certainty, and how humility coexists with purpose when the traveler depends on people whose lands he traverses.

The book’s influence radiated beyond its immediate news value. It helped define the public image of the special correspondent as someone who could make distant events legible while maintaining narrative drive. Its famous meeting entered popular memory and demonstrated how a single moment could summarize a vast labor of movement and reporting. In literature, it fortified the travel memoir’s claim to seriousness by wedding documentation to suspense. In journalism, it showed how a clear mission could organize complex material for a wide readership. Its presence can be felt wherever reportage and adventure are made to reinforce each other.

For contemporary audiences, the book remains compelling as both story and artifact. Readers seeking an account of endurance will find it; those interested in media history will see how a newspaper assignment became a durable narrative; and those attentive to ethics will encounter the challenges of writing across cultural and power differences. The work models meticulous field reporting under pressure while also exposing the limitations of its frame. Engaging it today encourages a double vision: to appreciate its craft and momentum and to interrogate the perspectives it carries, thereby learning from its achievements and its blind spots.

Ultimately, How I Found Livingstone endures because it combines a clear purpose with a human-scale drama of search and recognition. It evokes landscapes and labors while foregrounding the discipline of turning uncertainty into knowledge. Themes of perseverance, responsibility, and the interpretive act of seeing bind the chapters into a whole that still reads with urgency. Its lasting appeal lies in this fusion: a reporter’s steadiness, a traveler’s curiosity, and a reader’s invitation to weigh evidence alongside wonder. In revisiting it, we confront both the courage and the constraints of its age—and find reasons, still, to follow the path it clears.

Synopsis

Henry M. Stanley’s How I Found Livingstone recounts the New York Herald’s commission to locate Dr. David Livingstone, whose silence from Central Africa had stirred concern. The narrative begins in Zanzibar, where Stanley gathers funds, permissions, and supplies, and learns the rules of the coastal caravan trade. He recruits porters, interpreters, and guards, and amasses cloth, beads, and wire for payments along the route. Stanley outlines his objective, reviews reports on Livingstone’s last known movements near Lake Tanganyika, and describes the practical planning—routes, seasons, and contingencies—needed to move a large party from the coast into the interior with minimal delay.

Crossing to the mainland at Bagamoyo, Stanley organizes his caravan and begins the inland march. Early progress across the coast and the hills of Usagara is slowed by illness, desertions, and disputes over wages and loads. He explains the practice of paying transit tolls to local chiefs, particularly through Ugogo, where hongo levies and water scarcity force careful negotiation. The narrative details daily routines, methods to maintain discipline, and the constant balancing of speed with the health of men and animals. Geography, climate, and trade customs are observed alongside the practical realities of provisioning a moving column.

Entering Unyamwezi, Stanley finds the main route disrupted by regional conflict, notably the war associated with Mirambo that endangers caravans and settlements. He halts at Unyanyembe (Tabora), fortifies his camp, and coordinates with local Arab and Swahili traders while assessing risks. The text records skirmishes in the region and the strategic decision to delay rather than force a passage. Stanley explains supply constraints, the importance of reliable guides, and the need to reshape plans around political realities. After gathering information, he selects a safer, longer arc south and west to bypass contested territory and continue toward Lake Tanganyika.

The caravan resumes, taking a circuit through lesser-traveled country, facing forests, plateaus, and difficult river crossings. Sickness recurs, and constant bargaining for food and passage remains essential. Stanley notes the languages, trade goods, and customs encountered, illustrating how diplomacy underpins movement. The party eventually reaches the lakeside town of Ujiji, a major depot on Lake Tanganyika. There, Stanley learns Livingstone has recently arrived. The account of their meeting is direct and calm, with the famously understated greeting, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" confirming the objective. Relief, formal introductions, and local celebrations follow the identification.

Stanley immediately provides Livingstone with clothing, food, and medicines, and learns about the elder explorer’s losses and ill health. Livingstone shares journals, maps, and conclusions from years in the field, emphasizing unverified river systems to the west. Stanley summarizes these exchanges, presenting Livingstone’s priorities and unresolved geographic questions. Together they review routes and resources available in Ujiji, plan a short investigation to clarify the lake’s hydrology, and restore Livingstone’s strength and supplies. The narrative remains factual, detailing what was found, what remained uncertain, and the practical steps taken to consolidate information before any broader resumption of exploration.

With canoes and crews secured at Ujiji, the two men undertake a voyage on Lake Tanganyika toward its northern reaches. Stanley records weather, shoreline settlements, and navigational challenges, along with observations on trade and fisheries. Near the Rusizi, they verify that the river enters the lake rather than exits it, reducing the likelihood that Tanganyika drains northward. This determination narrows the field of possible Nile sources and clarifies the region’s hydrology. The party returns to Ujiji with improved maps and notes, and Stanley summarizes the evidentiary basis for these conclusions, distinguishing between confirmed findings and hypotheses still requiring further travel.

After weeks of cooperation, their paths diverge. Stanley, having fulfilled his commission, prepares to return to the coast with news, while Livingstone resolves to continue inland to investigate the Lualaba and related waterways. Stanley arranges additional supplies and messengers, commits to publicize Livingstone’s situation, and secures letters for authorities and friends. Their farewell is practical and dignified. The account emphasizes the limited but essential mission completed—finding, relieving, and reporting on Livingstone—while acknowledging that key geographical uncertainties remain. Stanley frames next steps as a matter of relay: resupply, communication, and the continuation of scientific inquiry by the senior explorer.

The homeward journey retraces parts of the southern route, still requiring tolls, diplomacy, and careful management of health and provisions. Stanley describes reassembling porters, avoiding conflict zones, and protecting stores. Reaching the coast, he dispatches reports and letters to confirm Livingstone’s safety and summarize the expedition’s findings. He credits consular assistance and Zanzibar authorities, details expenses and caravan organization, and notes the response of readers and officials abroad. The narrative closes the operational loop: departure, inland travel, discovery, verification, and return, with attention to accuracy, documentation, and the roles of African guides, porters, and coastal intermediaries.

Overall, How I Found Livingstone is a factual travel narrative focused on logistics, negotiation, and observation in service of a single, defined objective. It conveys the caravan system of East Africa, the political and environmental constraints on movement, and the value of local knowledge. The book’s key contributions include confirming Livingstone’s condition, establishing contact and resupply, and clarifying parts of Lake Tanganyika’s hydrography. Stanley avoids extended theorizing, presenting evidence, routes, and incidents in sequence. The underlying message is practical: perseverance, planning, and partnership can resolve complex tasks, advance geographic understanding, and translate scattered reports into verifiable, public knowledge.

Historical Context

Set chiefly in 1871, the narrative unfolds across the East African coast and the central caravan routes leading to Lake Tanganyika. The book’s geography spans Zanzibar, a maritime entrepôt in the Indian Ocean, Bagamoyo on the mainland, Unyanyembe (Tabora) in the Nyamwezi country, and Ujiji, the Arab-Swahili depot on Tanganyika’s shore. This was a frontier of commercial expansion and political flux, where inland polities negotiated with coastal merchants and their porters. The period preceded the formal “Scramble for Africa,” yet imperial consuls, naval patrols, and missionary stations already exerted influence. Stanley’s journey charts this interlocked world of markets, caravan paths, and contested sovereignties.

Zanzibar in the late 1860s and early 1870s served as the hinge of East Africa’s ivory and slave trades and the staging ground for expeditions into the interior. The Omani-Zanzibari sultans maintained a maritime empire of clove plantations and commercial stations, while Arab-Swahili caravans organized the transport of ivory from the Great Lakes. Inland, Nyamwezi, Hehe, and other societies controlled corridors and tolls, and Ujiji functioned as a hub for boats on Lake Tanganyika. Stanley’s account captures this mosaic: a coastal court culture intertwined with Islamic networks, a caravan economy dependent on African porters, and interior politics that could facilitate or obstruct travel.

After Sultan Said bin Sultan’s death in 1856, British arbitration in 1861 divided his dominions into Muscat and Zanzibar, cementing Zanzibar’s autonomy under Sultan Majid (r. 1856–1870) and then Barghash (r. 1870–1888). The island’s prosperity rested on cloves, ivory brokerage, and the inland slave trade, with Bagamoyo as the mainland terminus. European consuls in Zanzibar monitored commerce and, increasingly, slavery. How I Found Livingstone opens in this milieu. Stanley negotiates permissions at the Zanzibari court and organizes his caravan on the coast, revealing how the sultanate’s institutions, customs duties, and merchant houses framed the very possibility of a transcontinental search for Livingstone.

The 1871 New York Herald expedition to find Dr. David Livingstone emerged from the era’s globalizing press. James Gordon Bennett, Jr., proprietor of the Herald, commissioned Henry M. Stanley in 1869 to locate the missing explorer. Stanley traveled via the Mediterranean and the Red Sea to Zanzibar, recruited a contingent of nearly 200 porters and askaris, and assembled trade goods to purchase passage inland. The mission’s objective joined journalism with geography: to verify whether Livingstone survived in the interior and to gather news from an area still unmapped by Europeans. The book recounts this preparation and the negotiation of authority with coastal officials and caravan leaders.

Stanley’s route followed established caravan roads: from Bagamoyo across Ugogo and Unyamwezi to Unyanyembe (Tabora), where war conditions delayed progress. He staged supplies, secured escorts, and split his parties to navigate hostile zones. Proceeding westward, he crossed Uvinza and entered Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika, where, on 10 November 1871, he greeted the ailing Livingstone—an encounter that became emblematic of nineteenth-century exploration. The narrative chronicles fever, famine prices, desertions, and the careful use of cloth and beads as currency. These logistical details are central historical evidence of how caravans functioned and how inland commerce and politics shaped movement and safety.

Beyond the dramatic meeting, the expedition illustrates the operational culture of long-distance caravans: chains of headmen, interpreters, gun bearers, and Wangwana (freedmen) porters; rationing of grain and beads; and reliance on local markets. Stanley forged alliances with chiefs, purchased carriers in districts with food, and avoided contested paths. His record of payrolls, loads, and desertions aligns with contemporary accounts of the interior economy, where cloth types (merikani, kaniki) had calibrated value. How I Found Livingstone thereby documents the practical infrastructures—financial, diplomatic, and logistical—underpinning nineteenth-century exploration and reveals how European objectives were embedded in African trade systems.

The Mirambo War (1871–1872) disrupted the central route. Mirambo, a Nyamwezi leader from Urambo, consolidated power by controlling caravan corridors, battling Arab-Swahili merchants and their allies at Unyanyembe (Tabora). In mid-1871, fighting led to sieges, the burning of settlements, and the blocking of roads. Caravans were halted or diverted; tolls increased; escorts became essential. Stanley’s progress stalled at Unyanyembe, and he planned alternative approaches to Ujiji, timing his movements to avoid active fronts. The book’s descriptions of fortified positions, negotiations, and rumor networks provide firsthand testimony of how regional warfare shaped commerce and travel in the Tanzanian interior during this period.

The East African slave trade, intertwined with ivory, remained robust into the early 1870s. Captives from the interior were marched to coastal depots and shipped across the Indian Ocean. British diplomatic pressure culminated in the 1873 Anglo-Zanzibari treaty, compelling Sultan Barghash to close the Zanzibar slave market and prohibit exports by sea, though inland slaving persisted. In July 1871, at Nyangwe on the Lualaba, Livingstone witnessed a massacre of market-goers by slavers, an atrocity he reported to Stanley months later. How I Found Livingstone integrates these reports with Stanley’s observations of coffles and manacles, making the book an important documentary source for the trade’s late phase.

David Livingstone’s final journeys frame the mission. After the Zambezi Expedition (1858–1864), he returned to East Africa in 1866 to investigate the watersheds of the Lualaba and the Nile-Congo question. He traveled from Zanzibar through Nyasa and Tanganyika regions, reaching Manyema but suffered illness and loss of porters. His correspondence failed to reach Europe reliably after about 1869, prompting fears for his life. The Royal Geographical Society and the wider public debated his fate. Stanley’s commission arose from this uncertainty. In the book, Livingstone’s maps and journals—recovered at Ujiji—anchor a historical record of inland rivers and of the hardships of transcontinental fieldwork.

Mid-century geographical controversies supplied intellectual stakes. Richard F. Burton and John Hanning Speke reached Lake Tanganyika (1858), and Speke identified Lake Victoria, claiming it as the Nile source (1858; confirmed with James Grant in 1862). Burton and Speke’s dispute culminated in London debates in 1864, yet Tanganyika’s hydrology remained unresolved. The Royal Geographical Society fostered expeditions to clarify these issues. Stanley’s narrative engages these scientific questions, relaying Livingstone’s contention that the Lualaba flowed northward but questioning its relation to the Nile. How I Found Livingstone thus mirrors the period’s empirical ethos, measuring rivers, testing assertions, and integrating local geographic knowledge.

In December 1871, Stanley and Livingstone conducted a boat reconnaissance on Lake Tanganyika to assess inflows and possible outlets. They confirmed the Ruzizi River entered the lake from the north near present-day Burundi, weakening claims of a northern outlet to the Nile. They saw no clear egress, not yet identifying the Lukuga’s seasonal discharge westward (more fully noted by Verney Lovett Cameron in 1874–1875). Stanley’s account details soundings, bearings, and coastal settlements around Ujiji. The book connects exploration directly to scientific inference, demonstrating how incremental observations on currents and river mouths influenced broader debates on African hydrography.

The Arab-Swahili caravan system underwrote inland commerce. Traders organized seasonally timed departures, contracted headmen, and conveyed cloth, beads, and brass wire inland, returning with ivory and captives. Key entrepôts included Tabora (Unyanyembe) and Ujiji, where inland chiefs levied tolls and forged alliances. Guns and gunpowder were strategic commodities. Stanley’s reliance on these networks—hiring porters, buying rations, bartering safe passage—anchors the narrative in the material economy of the region. His lists of tariff-like payments and gifts to chiefs corroborate how political authority and commerce were fused, and how knowledge of routes and markets, held by African and coastal intermediaries, guided European travelers.

Missionary enterprises shaped the moral and logistical landscape. The Universities’ Mission to Central Africa (UMCA), after setbacks on the Shire Highlands (1861–1862), relocated to Zanzibar under Bishop Tozer and later Edward Steere, founding schools for freed slaves at Mbweni. The Holy Ghost Fathers established a Catholic mission at Bagamoyo in 1868, aiding ransomed captives and offering hospitality to travelers. These missions mediated between consuls, sultans, and local communities. In Stanley’s narrative, missions provide intelligence, shelter, and moral commentary on slavery. Their presence also exemplifies how Christian abolitionist agendas intersected with, and sometimes depended upon, the same caravan circuits that moved goods and people inland.

A revolution in communications underpinned the enterprise. The successful 1866 transatlantic telegraph cable and expanding cable networks enabled rapid transmission of news. James Gordon Bennett, Jr. cultivated sensational, global reporting in the New York Herald, financing distant correspondents as part of a competitive press market. Stanley filed dispatches en route where possible, and his book emerged from this reportage. The connection is explicit: How I Found Livingstone is both geographical document and media event, reflecting how nineteenth-century journalism could mobilize capital, public attention, and diplomatic access to penetrate regions beyond regular imperial administration.

British consular diplomacy in Zanzibar provided a political frame. Sir John Kirk, consul and later consul-general (from 1866), advised Sultan Barghash and pressed anti-slavery measures culminating in the 1873 treaty. Consuls issued letters of introduction, facilitated supplies, and coordinated with the Royal Navy’s local presence. Stanley consulted the consulate, navigated customs, and leveraged diplomatic goodwill to secure cooperation from coastal authorities. The book echoes these ties, revealing how exploratory ventures often depended on quasi-official backing, even when led by private newspapers, and how British policy—commercial protection, abolitionism, and strategic oversight—shaped the conditions of travel and publication.

As a social and political critique, the book exposes the structural violence of the caravan world. Stanley documents slave coffles, markets distorted by war and famine, and the coercive power of guns and trade monopolies. He describes porters’ mortality from disease, the harsh discipline of caravan leaders, and the vulnerability of villages to raiding. By giving dates, place names, and prices, he renders exploitation legible as a system, not merely as isolated episodes. The narrative’s attention to the Mirambo War and to the mechanics of tribute and tolls highlights how commercial interests and militarized authority preyed upon communities and travelers alike.

The work also interrogates imperial ambivalence. While aligned with abolitionist sentiment and scientific mapping, it reveals how European aims relied on local hierarchies, forced labor, and media sensationalism to achieve results. Stanley’s sympathy for African auxiliaries sits beside acceptance of punitive measures against deserters, reflecting class and racial asymmetries of the age. His collaboration with consuls and sultans—necessary for passage—illustrates the convergence of humanitarian rhetoric with strategic power. By publicizing Livingstone’s testimony on atrocities and by quantifying the costs and casualties of movement, the book critiques the era’s injustices even as it supplies the knowledge later mobilized for imperial expansion.

Author Biography

Henry Morton Stanley was a Welsh-born journalist, explorer, and author whose career epitomized the ambitions and contradictions of late nineteenth-century imperial exploration. Rising to fame through his reporting and expeditions in Africa, he became one of the most widely recognized figures of the Victorian era. His books, drawn from field notebooks and dispatches, helped shape public perceptions of the African interior for European and American readers. Celebrated for feats of endurance and geographic discovery, he was also a controversial participant in colonial projects whose human costs have been extensively scrutinized. Stanley’s legacy is thus both literary and political, bridging journalism, exploration, and empire.

Stanley’s early life in Wales involved limited formal education, followed by years of self-reliance and travel that fostered a practical schooling in seamanship, logistics, and reportage. As a young man he reached the United States, where he gravitated toward journalism. The craft of the newspaper correspondent—rapid observation, concise description, and a flair for narrative—proved a decisive influence on his writing. War reporting and frontier assignments tested his endurance and honed his ability to organize men and materials under pressure. These experiences, more than classroom study, formed the foundation of his later career, establishing habits of meticulous note-taking, map sketching, and on-the-move composition.

Stanley achieved international celebrity after undertaking a widely publicized mission for the New York Herald to locate the missing Scottish missionary-explorer David Livingstone in East-Central Africa. Their meeting at Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika in the early 1870s—later memorialized by a now-famous phrase—instantly propelled Stanley into the first rank of global reporters. He transformed the expedition into a bestselling narrative, How I Found Livingstone, whose blend of on-the-ground detail, serialized suspense, and dramatic pacing set a model for adventure reportage. The book established him as a writer who could translate arduous travel into vivid scenes for a mass readership, while also amplifying his reputation as an organizer and leader.

Building on that success, Stanley led a trans-African expedition in the mid-to-late 1870s that traced the Congo River’s course to the Atlantic and surveyed portions of the Great Lakes region. The journey, notable for its logistical complexity and high attrition, underpinned his two-volume Through the Dark Continent. In those pages, he presented itineraries, maps, and observations on terrain, climate, and trade routes, embedding his narrative in the cartographic and commercial priorities of the era. The work was celebrated by many contemporaries for its geographic contributions and narrative drive, even as it reflected prevailing European assumptions about Africa and framed exploration as a prelude to commerce and governance.

In the early 1880s, Stanley worked to establish stations, transport corridors, and agreements along the Congo on behalf of interests associated with King Leopold II. His activities helped lay the groundwork for the Congo Free State. The project, promoted at the time under banners of scientific progress and the suppression of the slave trade, quickly drew criticism for coercive labor practices and violence. Stanley defended his role in The Congo and the Founding of its Free State, a mid-1880s account that blended justification, policy argument, and travel narrative. Subsequent scholarship has scrutinized both the book and the enterprise, documenting the profound human costs that accompanied territorial claims and extraction.

Stanley returned to Central Africa in the late 1880s to lead the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, a venture marked by arduous conditions, internal conflicts, and heavy loss of life. He recounted it in In Darkest Africa, published in the early 1890s, combining field diaries with maps and roster-like detail. The book sold widely, further cementing his stature as a premier narrator of exploration, while also intensifying debates about conduct, ethics, and aims. In these years he lectured extensively and entered public life in Britain, receiving honors and serving in Parliament in the late 1890s. His prose, though firmly of its time, remained influential in the travel and adventure canon.

In his later years, Stanley withdrew from expedition work, turning to public speaking, reflection, and preparation of his papers. He died in the early twentieth century, and a posthumous autobiography assembled from his writings expanded the record of his early struggles and professional formation. Today his books—especially How I Found Livingstone, Through the Dark Continent, The Congo and the Founding of its Free State, and In Darkest Africa—are read both as primary sources on Victorian exploration and as documents implicated in imperial ideology. Scholars mine them for geographical data, media history, and colonial discourse, while the iconic meeting with Livingstone endures as a cultural shorthand for the era’s ambitions and blind spots.

How I Found Livingstone

CHAPTER I.— INTRODUCTORY. MY INSTRUCTIONS TO FIND AND RELIEVE LIVINGSTONE.

On the sixteenth day of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-nine, I was in Madrid, fresh from the carnage at Valencia. At 10 A.M. Jacopo, at No.— Calle de la Cruz, handed me a telegram: It read, "Come to Paris on important business." The telegram was from Mr. James Gordon Bennett, jun.[1], the young manager of the 'New York Herald.'

Down came my pictures from the walls of my apartments on the second floor; into my trunks went my books and souvenirs, my clothes were hastily collected, some half washed, some from the clothes-line half dry, and after a couple of hours of hasty hard work my portmanteaus were strapped up and labelled "Paris."

At 3 P.M. I was on my way, and being obliged to stop at Bayonne a few hours, did not arrive at Paris until the following night. I went straight to the 'Grand Hotel,' and knocked at the door of Mr. Bennett's room.

"Come in," I heard a voice say. Entering, I found Mr. Bennett in bed. "Who are you?" he asked.

"My name is Stanley," I answered.

"Ah, yes! sit down; I have important business on hand for you."

After throwing over his shoulders his robe-de-chambre Mr. Bennett asked, "Where do you think Livingstone is?"

"I really do not know, sir."

"Do you think he is alive?"

"He may be, and he may not be," I answered.

"Well, I think he is alive, and that he can be found, and I am going to send you to find him."

"What!" said I, "do you really think I can find Dr Livingstone? Do you mean me to go to Central Africa?"

"Yes; I mean that you shall go, and find him wherever you may hear that he is, and to get what news you can of him, and perhaps"—delivering himself thoughtfully and deliberately—"the old man may be in want:—take enough with you to help him should he require it. Of course you will act according to your own plans, and do what you think best—BUT FIND LIVINGSTONE!"

Said I, wondering at the cool order of sending one to Central Africa to search for a man whom I, in common with almost all other men, believed to be dead, "Have you considered seriously the great expense you are likely, to incur on account of this little journey?"

"What will it cost?" he asked abruptly.

"Burton and Speke[2]'s journey to Central Africa cost between £3,000 and £5,000, and I fear it cannot be done under £2,500."

"Well, I will tell you what you will do. Draw a thousand pounds now; and when you have gone through that, draw another thousand, and when that is spent, draw another thousand, and when you have finished that, draw another thousand, and so on; but, FIND LIVINGSTONE."

Surprised but not confused at the order—for I knew that Mr. Bennett when once he had made up his mind was not easily drawn aside from his purpose—I yet thought, seeing it was such a gigantic scheme, that he had not quite considered in his own mind the pros and cons of the case; I said, "I have heard that should your father die you would sell the 'Herald' and retire from business."

"Whoever told you that is wrong, for there is not, money enough in New York city to buy the 'New York Herald.' My father has made it a great paper, but I mean to make it greater. I mean that it shall be a newspaper in the true sense of the word. I mean that it shall publish whatever news will be interesting to the world at no matter what cost."

"After that," said I, "I have nothing more to say. Do you mean me to go straight on to Africa to search for Dr. Livingstone?"

"No! I wish you to go to the inauguration of the Suez Canal first, and then proceed up the Nile. I hear Baker is about starting for Upper Egypt. Find out what you can about his expedition, and as you go up describe as well as possible whatever is interesting for tourists; and then write up a guide—a practical one—for Lower Egypt; tell us about whatever is worth seeing and how to see it.

"Then you might as well go to Jerusalem; I hear Captain Warren is making some interesting discoveries there. Then visit Constantinople, and find out about that trouble between the Khedive and the Sultan.

"Then—let me see—you might as well visit the Crimea and those old battle-grounds, Then go across the Caucasus[5] to the Caspian Sea; I hear there is a Russian expedition bound for Khiva. From thence you may get through Persia to India; you could write an interesting letter from Persepolis.

"Bagdad will be close on your way to India; suppose you go there, and write up something about the Euphrates Valley Railway. Then, when you have come to India, you can go after Livingstone. Probably you will hear by that time that Livingstone is on his way to Zanzibar; but if not, go into the interior and find him. If alive, get what news of his discoveries you can; and if you find he is dead, bring all possible proofs of his being dead. That is all. Good-night, and God be with you."

"Good-night, Sir," I said, "what it is in the power of human nature to do I will do[1q]; and on such an errand as I go upon, God will be with me."

I lodged with young Edward King, who is making such a name in New England. He was just the man who would have delighted to tell the journal he was engaged upon what young Mr. Bennett was doing, and what errand I was bound upon.

I should have liked to exchange opinions with him upon the probable results of my journey, but I dared not do so. Though oppressed with the great task before me, I had to appear as if only going to be present at the Suez Canal. Young King followed me to the express train bound for Marseilles, and at the station we parted: he to go and read the newspapers at Bowles' Reading-room—I to Central Africa and—who knows?

There is no need to recapitulate what I did before going to Central Africa.

I went up the Nile and saw Mr. Higginbotham, chief engineer in Baker's Expedition, at Philae, and was the means of preventing a duel between him and a mad young Frenchman, who wanted to fight Mr. Higginbotham with pistols, because that gentleman resented the idea of being taken for an Egyptian, through wearing a fez cap. I had a talk with Capt. Warren at Jerusalem, and descended one of the pits with a sergeant of engineers to see the marks of the Tyrian workmen on the foundation-stones of the Temple of Solomon. I visited the mosques of Stamboul with the Minister Resident of the United States, and the American Consul-General. I travelled over the Crimean battle-grounds with Kinglake's glorious books for reference in my hand. I dined with the widow of General Liprandi at Odessa. I saw the Arabian traveller Palgrave at Trebizond, and Baron Nicolay, the Civil Governor of the Caucasus, at Tiflis. I lived with the Russian Ambassador while at Teheran, and wherever I went through Persia I received the most hospitable welcome from the gentlemen of the Indo-European Telegraph Company; and following the examples of many illustrious men, I wrote my name upon one of the Persepolitan monuments. In the month of August, 1870, I arrived in India.

On the 12th of October I sailed on the barque 'Polly' from Bombay to Mauritius. As the 'Polly' was a slow sailer, the passage lasted thirty-seven days. On board this barque was a William Lawrence Farquhar—hailing from Leith, Scotland—in the capacity of first-mate. He was an excellent navigator, and thinking he might be useful to me, I employed him; his pay to begin from the date we should leave Zanzibar for Bagamoyo. As there was no opportunity of getting, to Zanzibar direct, I took ship to Seychelles. Three or four days after arriving at Mahe, one of the Seychelles group, I was fortunate enough to get a passage for myself, William Lawrence Farquhar, and an Arab boy from Jerusalem, who was to act as interpreter—on board an American whaling vessel, bound for Zanzibar; at which port we arrived on the 6th of January, 1871.

I have skimmed over my travels thus far, because these do not concern the reader. They led over many lands, but this book is only a narrative of my search after Livingstone, the great African traveller. It is an Icarian flight of journalism, I confess; some even have called it Quixotic; but this is a word I can now refute, as will be seen before the reader arrives at the "Finis."

I have used the word "soldiers" in this book. The armed escort a traveller engages to accompany him into East Africa is composed of free black men, natives of Zanzibar, or freed slaves from the interior, who call themselves "askari[3]," an Indian name which, translated, means "soldiers." They are armed and equipped like soldiers, though they engage themselves also as servants; but it would be more pretentious in me to call them servants, than to use the word "soldiers;" and as I have been more in the habit of calling them soldiers than "my watuma"—servants—this habit has proved too much to be overcome. I have therefore allowed the word "soldiers" to appear, accompanied, however, with this apology.

But it must be remembered that I am writing a narrative of my own adventures and travels, and that until I meet Livingstone, I presume the greatest interest is attached to myself, my marches, my troubles, my thoughts, and my impressions. Yet though I may sometimes write, "my expedition," or "my caravan," it by no means follows that I arrogate to myself this right. For it must be distinctly understood that it is the "'New York Herald' Expedition," and that I am only charged with its command by Mr. James Gordon Bennett, the proprietor of the 'New York Herald,' as a salaried employ of that gentleman.

One thing more; I have adopted the narrative form of relating the story of the search, on account of the greater interest it appears to possess over the diary form, and I think that in this manner I avoid the great fault of repetition for which some travellers have been severely criticised.

CHAPTER II. — ZANZIBAR.

On the morning of the 6th January, 1871, we were sailing through the channel that separates the fruitful island of Zanzibar from Africa. The high lands of the continent loomed like a lengthening shadow in the grey of dawn. The island lay on our left, distant but a mile, coming out of its shroud of foggy folds bit by bit as the day advanced, until it finally rose clearly into view, as fair in appearance as the fairest of the gems of creation. It appeared low, but not flat; there were gentle elevations cropping hither and yon above the languid but graceful tops of the cocoa-trees that lined the margin of the island, and there were depressions visible at agreeable intervals, to indicate where a cool gloom might be found by those who sought relief from a hot sun. With the exception of the thin line of sand, over which the sap-green water rolled itself with a constant murmur and moan, the island seemed buried under one deep stratum of verdure.

The noble bosom of the strait bore several dhows speeding in and out of the bay of Zanzibar with bellying sails. Towards the south, above the sea line of the horizon, there appeared the naked masts of several large ships, and to the east of these a dense mass of white, flat-topped houses. This was Zanzibar, the capital of the island;—which soon resolved itself into a pretty large and compact city, with all the characteristics of Arab architecture. Above some of the largest houses lining the bay front of the city streamed the blood-red banner of the Sultan, Seyd Burghash, and the flags of the American, English, North German Confederation, and French Consulates. In the harbor were thirteen large ships, four Zanzibar men-of-war, one English man-of-war—the 'Nymphe,' two American, one French, one Portuguese, two English, and two German merchantmen, besides numerous dhows hailing from Johanna and Mayotte of the Comoro Islands, dhows from Muscat and Cutch—traders between India, the Persian Gulf, and Zanzibar.

It was with the spirit of true hospitality and courtesy that Capt. Francis R. Webb, United States Consul, (formerly of the United States Navy), received me. Had this gentleman not rendered me such needful service, I must have condescended to take board and lodging at a house known as "Charley's," called after the proprietor, a Frenchman, who has won considerable local notoriety for harboring penniless itinerants, and manifesting a kindly spirit always, though hidden under such a rugged front; or I should have been obliged to pitch my double-clothed American drill tent on the sandbeach of this tropical island, which was by no means a desirable thing.

But Capt. Webb's opportune proposal to make his commodious and comfortable house my own; to enjoy myself, with the request that I would call for whatever I might require, obviated all unpleasant alternatives.

One day's life at Zanzibar made me thoroughly conscious of my ignorance respecting African people and things in general. I imagined I had read Burton and Speke through, fairly well, and that consequently I had penetrated the meaning, the full importance and grandeur, of the work I was about to be engaged upon. But my estimates, for instance, based upon book information, were simply ridiculous, fanciful images of African attractions were soon dissipated, anticipated pleasures vanished, and all crude ideas began to resolve themselves into shape.

I strolled through the city. My general impressions are of crooked, narrow lanes, white-washed houses, mortar-plastered streets, in the clean quarter;—of seeing alcoves on each side, with deep recesses, with a fore-ground of red-turbaned Banyans, and a back-ground of flimsy cottons, prints, calicoes, domestics and what not; or of floors crowded with ivory tusks; or of dark corners with a pile of unginned and loose cotton; or of stores of crockery, nails, cheap Brummagem ware, tools, &c., in what I call the Banyan quarter;—of streets smelling very strong—in fact, exceedingly, malodorous, with steaming yellow and black bodies, and woolly heads, sitting at the doors of miserable huts, chatting, laughing, bargaining, scolding, with a compound smell of hides, tar, filth, and vegetable refuse, in the negro quarter;—of streets lined with tall, solid-looking houses, flat roofed, of great carved doors with large brass knockers, with baabs sitting cross-legged watching the dark entrance to their masters' houses; of a shallow sea-inlet, with some dhows, canoes, boats, an odd steam-tub or two, leaning over on their sides in a sea of mud which the tide has just left behind it; of a place called "M'nazi-Moya," "One Cocoa-tree," whither Europeans wend on evenings with most languid steps, to inhale the sweet air that glides over the sea, while the day is dying and the red sun is sinking westward; of a few graves of dead sailors, who paid the forfeit of their lives upon arrival in this land; of a tall house wherein lives Dr. Tozer, "Missionary Bishop of Central Africa," and his school of little Africans; and of many other things, which got together into such a tangle, that I had to go to sleep, lest I should never be able to separate the moving images, the Arab from the African; the African from the Banyan; the Banyan from the Hindi; the Hindi from the European, &c.

Zanzibar is the Bagdad, the Ispahan, the Stamboul, if you like, of East Africa. It is the great mart which invites the ivory traders from the African interior. To this market come the gum-copal, the hides, the orchilla weed, the timber, and the black slaves from Africa. Bagdad had great silk bazaars, Zanzibar has her ivory bazaars; Bagdad once traded in jewels, Zanzibar trades in gum-copal; Stamboul imported Circassian and Georgian slaves; Zanzibar imports black beauties from Uhiyow, Ugindo, Ugogo, Unyamwezi and Galla.

The same mode of commerce obtains here as in all Mohammedan countries—nay, the mode was in vogue long before Moses was born. The Arab never changes. He brought the custom of his forefathers with him when he came to live on this island. He is as much of an Arab here as at Muscat or Bagdad; wherever he goes to live he carries with him his harem, his religion, his long robe, his shirt, his slippers, and his dagger. If he penetrates Africa, not all the ridicule of the negroes can make him change his modes of life. Yet the land has not become Oriental; the Arab has not been able to change the atmosphere. The land is semi-African in aspect; the city is but semi-Arabian.

To a new-comer into Africa, the Muscat Arabs of Zanzibar are studies. There is a certain empressement about them which we must admire. They are mostly all travellers. There are but few of them who have not been in many dangerous positions, as they penetrated Central Africa in search of the precious ivory; and their various experiences have given their features a certain unmistakable air of-self-reliance, or of self-sufficiency; there is a calm, resolute, defiant, independent air about them, which wins unconsciously one's respect. The stories that some of these men could tell, I have often thought, would fill many a book of thrilling adventures.

For the half-castes I have great contempt. They are neither black nor white, neither good nor bad, neither to be admired nor hated. They are all things, at all times; they are always fawning on the great Arabs, and always cruel to those unfortunates brought under their yoke. If I saw a miserable, half-starved negro, I was always sure to be told he belonged to a half-caste. Cringing and hypocritical, cowardly and debased, treacherous and mean, I have always found him. He seems to be for ever ready to fall down and worship a rich Arab, but is relentless to a poor black slave. When he swears most, you may be sure he lies most, and yet this is the breed which is multiplied most at Zanzibar.

The Banyan is a born trader, the beau-ideal of a sharp money-making man. Money flows to his pockets as naturally as water down a steep. No pang of conscience will prevent him from cheating his fellow man. He excels a Jew, and his only rival in a market is a Parsee; an Arab is a babe to him. It is worth money to see him labor with all his energy, soul and body, to get advantage by the smallest fraction of a coin over a native. Possibly the native has a tusk, and it may weigh a couple of frasilahs, but, though the scales indicate the weight, and the native declares solemnly that it must be more than two frasilahs, yet our Banyan will asseverate and vow that the native knows nothing whatever about it, and that the scales are wrong; he musters up courage to lift it—it is a mere song, not much more than a frasilah. "Come," he will say, "close, man, take the money and go thy way. Art thou mad?" If the native hesitates, he will scream in a fury; he pushes him about, spurns the ivory with contemptuous indifference,—never was such ado about nothing; but though he tells the astounded native to be up and going, he never intends the ivory shall leave his shop.

The Banyans exercise, of all other classes, most influence on the trade of Central Africa. With the exception of a very few rich Arabs, almost all other traders are subject to the pains and penalties which usury imposes. A trader desirous to make a journey into the interior, whether for slaves or ivory, gum-copal, or orchilla weed, proposes to a Banyan to advance him $5,000, at 50, 60, or 70 per cent. interest. The Banyan is safe enough not to lose, whether the speculation the trader is engaged upon pays or not. An experienced trader seldom loses, or if he has been unfortunate, through no deed of his own, he does not lose credit; with the help of the Banyan, he is easily set on his feet again.

We will suppose, for the sake of illustrating how trade with the interior is managed, that the Arab conveys by his caravan $5,000's worth of goods into the interior. At Unyanyembe the goods are worth $10,000; at Ujiji, they are worth $15,000: they have trebled in price. Five doti, or $7.50, will purchase a slave in the markets of Ujiji that will fetch in Zanzibar $30. Ordinary menslaves may be purchased for $6 which would sell for $25 on the coast. We will say he purchases slaves to the full extent of his means—after deducting $1,500 expenses of carriage to Ujiji and back—viz. $3,500, the slaves—464 in number, at $7-50 per head—would realize $13,920 at Zanzibar! Again, let us illustrate trade in ivory. A merchant takes $5,000 to Ujiji, and after deducting $1,500 for expenses to Ujiji, and back to Zanzibar, has still remaining $3,500 in cloth and beads, with which he purchases ivory. At Ujiji ivory is bought at $20 the frasilah, or 35 lbs., by which he is enabled with $3,500 to collect 175 frasilahs, which, if good ivory, is worth about $60 per frasilah at Zanzibar. The merchant thus finds that he has realized $10,500 net profit! Arab traders have often done better than this, but they almost always have come back with an enormous margin of profit.

The next people to the Banyans in power in Zanzibar are the Mohammedan Hindis. Really it has been a debateable subject in my mind whether the Hindis are not as wickedly determined to cheat in trade as the Banyans. But, if I have conceded the palm to the latter, it has been done very reluctantly. This tribe of Indians can produce scores of unconscionable rascals where they can show but one honest merchant. One of the honestest among men, white or black, red or yellow, is a Mohammedan Hindi called Tarya Topan. Among the Europeans at Zanzibar, he has become a proverb for honesty, and strict business integrity. He is enormously wealthy, owns several ships and dhows, and is a prominent man in the councils of Seyd Burghash. Tarya has many children, two or three of whom are grown-up sons, whom he has reared up even as he is himself. But Tarya is but a representative of an exceedingly small minority.

The Arabs, the Banyans, and the Mohammedan Hindis, represent the higher and the middle classes. These classes own the estates, the ships, and the trade. To these classes bow the half-caste and the negro.

The next most important people who go to make up the mixed population of this island are the negroes. They consist of the aborigines, Wasawahili, Somalis, Comorines, Wanyamwezi, and a host of tribal representatives of Inner Africa.

To a white stranger about penetrating Africa, it is a most interesting walk through the negro quarters of the Wanyamwezi and the Wasawahili. For here he begins to learn the necessity of admitting that negroes are men, like himself, though of a different colour; that they have passions and prejudices, likes and dislikes, sympathies and antipathies, tastes and feelings, in common with all human nature. The sooner he perceives this fact, and adapts himself accordingly, the easier will be his journey among the several races of the interior. The more plastic his nature, the more prosperous will be his travels.

Though I had lived some time among the negroes of our Southern States, my education was Northern, and I had met in the United States black men whom I was proud to call friends. I was thus prepared to admit any black man, possessing the attributes of true manhood or any good qualities, to my friendship, even to a brotherhood with myself; and to respect him for such, as much as if he were of my own colour and race. Neither his colour, nor any peculiarities of physiognomy should debar him with me from any rights he could fairly claim as a man. "Have these men—these black savages from pagan Africa," I asked myself, "the qualities which make man loveable among his fellows? Can these men—these barbarians—appreciate kindness or feel resentment like myself?" was my mental question as I travelled through their quarters and observed their actions. Need I say, that I was much comforted in observing that they were as ready to be influenced by passions, by loves and hates, as I was myself; that the keenest observation failed to detect any great difference between their nature and my own?

The negroes of the island probably number two-thirds of the entire population. They compose the working-class, whether enslaved or free. Those enslaved perform the work required on the plantations, the estates, and gardens of the landed proprietors, or perform the work of carriers, whether in the country or in the city. Outside the city they may be seen carrying huge loads on their heads, as happy as possible, not because they are kindly treated or that their work is light, but because it is their nature to be gay and light-hearted, because they, have conceived neither joys nor hopes which may not be gratified at will, nor cherished any ambition beyond their reach, and therefore have not been baffled in their hopes nor known disappointment.

Within the city, negro carriers may be heard at all hours, in couples, engaged in the transportation of clove-bags, boxes of merchandise, &c., from store to "godown" and from "go-down" to the beach, singing a kind of monotone chant for the encouragement of each other, and for the guiding of their pace as they shuffle through the streets with bare feet. You may recognise these men readily, before long, as old acquaintances, by the consistency with which they sing the tunes they have adopted. Several times during a day have I heard the same couple pass beneath the windows of the Consulate, delivering themselves of the same invariable tune and words. Some might possibly deem the songs foolish and silly, but they had a certain attraction for me, and I considered that they were as useful as anything else for the purposes they were intended.

The town of Zanzibar, situate on the south-western shore of the island, contains a population of nearly one hundred thousand inhabitants; that of the island altogether I would estimate at not more than two hundred thousand inhabitants, including all races.

The greatest number of foreign vessels trading with this port are American, principally from New York and Salem. After the American come the German, then come the French and English. They arrive loaded with American sheeting, brandy, gunpowder, muskets, beads, English cottons, brass-wire, china-ware, and other notions, and depart with ivory, gum-copal, cloves, hides, cowries, sesamum, pepper, and cocoa-nut oil.

The value of the exports from this port is estimated at $3,000,000, and the imports from all countries at $3,500,000.

The Europeans and Americans residing in the town of Zanzibar are either Government officials, independent merchants, or agents for a few great mercantile houses in Europe and America.

The climate of Zanzibar is not the most agreeable in the world. I have heard Americans and Europeans condemn it most heartily. I have also seen nearly one-half of the white colony laid up in one day from sickness. A noxious malaria is exhaled from the shallow inlet of Malagash, and the undrained filth, the garbage, offal, dead mollusks, dead pariah dogs, dead cats, all species of carrion, remains of men and beasts unburied, assist to make Zanzibar a most unhealthy city; and considering that it it ought to be most healthy, nature having pointed out to man the means, and having assisted him so far, it is most wonderful that the ruling prince does not obey the dictates of reason.

The bay of Zanzibar is in the form of a crescent, and on the south-western horn of it is built the city. On the east Zanzibar is bounded almost entirely by the Malagash Lagoon, an inlet of the sea. It penetrates to at least two hundred and fifty yards of the sea behind or south of Shangani Point. Were these two hundred and fifty yards cut through by a ten foot ditch, and the inlet deepened slightly, Zanzibar would become an island of itself, and what wonders would it not effect as to health and salubrity! I have never heard this suggestion made, but it struck me that the foreign consuls resident at Zanzibar might suggest this work to the Sultan, and so get the credit of having made it as healthy a place to live in as any near the equator. But apropos of this, I remember what Capt. Webb, the American Consul, told me on my first arrival, when I expressed to him my wonder at the apathy and inertness of men born with the indomitable energy which characterises Europeans and Americans, of men imbued with the progressive and stirring instincts of the white people, who yet allow themselves to dwindle into pallid phantoms of their kind, into hypochondriacal invalids, into hopeless believers in the deadliness of the climate, with hardly a trace of that daring and invincible spirit which rules the world.

"Oh," said Capt. Webb, "it is all very well for you to talk about energy and all that kind of thing, but I assure you that a residence of four or five years on this island, among such people as are here, would make you feel that it was a hopeless task to resist the influence of the example by which the most energetic spirits are subdued, and to which they must submit in time, sooner or later. We were all terribly energetic when we first came here, and struggled bravely to make things go on as we were accustomed to have them at home, but we have found that we were knocking our heads against granite walls to no purpose whatever. These fellows—the Arabs, the Banyans, and the Hindis—you can't make them go faster by ever so much scolding and praying, and in a very short time you see the folly of fighting against the unconquerable. Be patient, and don't fret, that is my advice, or you won't live long here."

There were three or four intensely busy men, though, at Zanzibar, who were out at all hours of the day. I know one, an American; I fancy I hear the quick pit-pat of his feet on the pavement beneath the Consulate, his cheery voice ringing the salutation, "Yambo!" to every one he met; and he had lived at Zanzibar twelve years.

I know another, one of the sturdiest of Scotchmen, a most pleasant-mannered and unaffected man, sincere in whatever he did or said, who has lived at Zanzibar several years, subject to the infructuosities of the business he has been engaged in, as well as to the calor and ennui of the climate, who yet presents as formidable a front as ever to the apathetic native of Zanzibar. No man can charge Capt. H. C. Fraser, formerly of the Indian Navy, with being apathetic.

I might with ease give evidence of the industry of others, but they are all my friends, and they are all good. The American, English, German, and French residents have ever treated me with a courtesy and kindness I am not disposed to forget. Taken as a body, it would be hard to find a more generous or hospitable colony of white men in any part of the world.