1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Quickie Classics

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

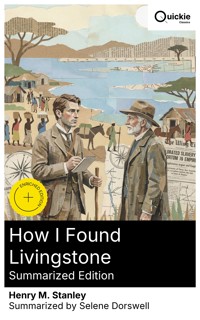

How I Found Livingstone (1872) recounts Henry M. Stanley's 1871 expedition from Zanzibar into the East African interior to locate the missing missionary-explorer, culminating at Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika with the laconic greeting, 'Dr. Livingstone, I presume?'. Combining brisk reportage with Victorian travelogue, Stanley details caravan logistics, illness, cartography, and encounters with Arab-Swahili traders and African communities. The prose shifts between sensational dispatch and careful observation, situating the journey amid newspaper-fueled exploration and debates over slavery, commerce, and geographical knowledge. A Welsh-born journalist who made his career with the New York Herald, Stanley was commissioned by James Gordon Bennett Jr. to turn a global scoop into imperial theater. Seasoned by war correspondence and driven by rivalry, he marshaled instruments, porters, and patronage from Zanzibar's court. His training shapes the book's episodic structure and evidentiary tone; his later African ventures and controversies illuminate the ambition animating this first major narrative. Recommended to readers of exploration history, media studies, and African historical geography, this classic rewards critical engagement. Read it for vivid route-maps and fieldcraft, and as a revealing document of Victorian publicity, courage, and prejudice. Quickie Classics summarizes timeless works with precision, preserving the author's voice and keeping the prose clear, fast, and readable—distilled, never diluted. Enriched Edition extras: Introduction · Synopsis · Historical Context · Author Biography · Brief Analysis · 4 Reflection Q&As · Editorial Footnotes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2026

Ähnliche

How I Found Livingstone (Summarized Edition)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Centering on the urgent disappearance of a famed explorer, How I Found Livingstone is a story in which a missing man becomes the axis of a transcontinental pursuit, where the ambitions of a young correspondent, the imperatives of a powerful newspaper, and the stubborn mysteries of Central Africa converge to test endurance, leadership, and conscience, tracing a path from ocean edge to inland lakes through fever, famine, negotiation, and doubt, while dramatizing how information travels, how reputations are made, and how the encounter between curiosity and power can illuminate landscapes even as it reveals the limits of those who seek to map them.

Henry M. Stanley’s book is a nonfiction travel narrative rooted in reportage, set largely along the caravan corridors of East and Central Africa during the early 1870s. First published in 1872, it grew out of his assignment as a journalist for the New York Herald to search for the missionary-explorer David Livingstone, whose whereabouts had become uncertain. The story moves from the coastal world linked to global trade into the interior, where distances stretch and information thins. Written in the idiom of its era, it positions exploration within a media-saturated age, balancing description of terrain with the practicalities of marching, provisioning, and command.

The premise is straightforward yet gripping: a newspaper-backed expedition must assemble men and supplies at the coast, choose a route, and advance toward rumors that point inland to the great lakes. Stanley narrates in the first person, with a brisk, insistently concrete style that catalogs obstacles and decisions while maintaining narrative momentum. Readers encounter depictions of climate, rivers, and forest, accounts of illness and recovery, and a tangle of negotiations with headmen and guides. The tone combines urgency with meticulous recordkeeping, producing a hybrid of adventure chronicle and field report that invites the reader to follow the march day by day without foreclosing suspense.

Endurance and logistics anchor the narrative, but the book also examines the authority of eyewitness writing and the reach of the press. A central theme is how knowledge is produced under pressure: maps are provisional, stories contradictory, and choices must be made with partial information. Cross-cultural encounter appears in the practical language of bargaining and alliance, revealing unequal power as well as mutual dependence along the routes. The expedition’s progress becomes a study in leadership, improvisation, and accountability. At the same time, the work registers the assumptions of its moment, encouraging contemporary readers to weigh its portrayals critically while attending to the immediacy of its detail.

For twenty-first-century readers, the book matters as both an action-filled document and a case study in media-driven exploration. It shows how journalism can mobilize resources, shape public curiosity, and impose deadlines on ventures that move at the pace of human feet. Its pages illuminate caravan economies, the costs of transport, and the human networks that make movement possible far from telegraph lines. It also exposes the biases and blind spots of its perspective, which are important to recognize when using it as historical evidence. Read with care, it becomes a resource for thinking about risk, verification, representation, and the ethics of attention.

The reading experience alternates between arduous march and reflective halt, with set pieces that turn geography into narrative propulsion. Stanley’s eye for sequence keeps the itinerary legible: distances are measured, rations are apportioned, scouts are sent, and decisions are timestamped by weather and terrain. He observes social dynamics within the caravan and the varying expectations of those encountered, without halting the forward movement of the quest. The prose favors clarity over ornament, yet it often dwells on rivers, escarpments, and sudden changes of sky that signal hazard or reprieve. The result is a textured account that rewards close attention to causes, effects, and the contingencies of travel.

Ultimately, this book endures because it situates the drama of a search within the larger drama of how the world was being narrated. It chronicles movement through unfamiliar ground while revealing the machinery that turned such movement into news, commerce, and reputation. As a primary account of a consequential expedition published in 1872, it offers evidence, contradictions, and textures that no summary can replace. As literature, it delivers suspense without artifice and detail without tedium. Approached with curiosity and skepticism in equal measure, it allows contemporary readers to study exploration from the inside while questioning the frames through which exploration was imagined.

Synopsis

How I Found Livingstone is Henry M. Stanley’s first-person narrative of his 1871–1872 expedition in East and Central Africa to locate the missing Scottish missionary-explorer David Livingstone. Written as a journalistic travel account and first published in 1872, it blends reportage, logistics, and observation with the sensibilities of a nineteenth-century correspondent working for the New York Herald. The book traces the venture from its conception and commissioning through the slow accumulation of resources, the inland march, and the pursuit of verified information. Stanley frames the search as both a practical task of movement and supply and an editorial quest for reliable, on-the-ground evidence.

Stanley begins on the Indian Ocean coast, chiefly in Zanzibar and the mainland port of Bagamoyo, where the caravan economy, Arab-Swahili trade houses, and complex patronage networks shape every decision. The narrative dwells on bargaining for cloth, beads, and wire—the currencies of the interior—and on negotiating contracts with porters and headmen. He details the hierarchy of caravan personnel, explains the function of interpreters, and describes how coastal markets provision long journeys. Throughout, he emphasizes the necessity of aligning European aims with practices already established by East African merchants, without which movement inland would be impossible.

The march from the coast introduces the routine of caravan travel: setting loads, managing rations, mediating disputes, and balancing speed with health. Stanley records heat, water scarcity in certain stretches, sudden storms, and the toll of fever. Diplomacy is constant; passage often depends on customary gifts and negotiated tribute. Chiefs, village elders, and guardians of routes must be addressed in the regional lingua franca, and misunderstandings can halt progress. The narrative’s focus remains on verification—separating rumor from actionable intelligence about the interior and, especially, evaluating reports of a European traveler said to be alive beyond the well-trodden trade belts.

In the central inland hub of Unyanyembe (modern Tabora), Stanley’s party intersects with larger caravan currents, Arab trading strongholds, and news of warfare. The book recounts how conflict destabilizes routes and forces delays, compelling him to reconfigure loads, reassess escorts, and weigh risks against the imperative to push on. He portrays Unyanyembe as both a sanctuary and a pressure point: a place to heal, gather information, and plan, yet also a theater where alliances and hostilities influence every next step. These chapters highlight the strategic patience required when geography and politics converge to obstruct travel.

When the route opens, Stanley opts for speed and maneuverability, describing a leaner advance with selected carriers and guides. The narrative emphasizes endurance under illness and scarcity, navigation by local knowledge, and the discipline necessary to prevent desertion. He sketches landscapes of dry plains, wooded highlands, and valleys leading toward the Great Lakes region, noting wildlife in passing but centering his account on people, paths, and provisions. As the party approaches watersheds feeding the continent’s interior basins, Stanley underscores how geography, trade, and rumor interlace, and how the caravan’s survival depends on reading all three correctly.

The final approach to the Lake Tanganyika corridor brings an intensification of reports about a European at Ujiji. Stanley narrates how he cross-checks testimonies from traders and villagers, tests distances against marching times, and conserves morale for the last stages. Arrival at Ujiji is presented as a carefully managed entrance to a major lakeside market community, with attention to local authorities and customs. The encounter that follows fulfills the expedition’s stated purpose without dwelling on rhetoric. Stanley’s account centers on confirmation—who is present, in what circumstances, and what can reliably be conveyed to the wider world.

The book then pauses to take stock of circumstances around the lake: the trading importance of Ujiji, the movements of canoes, and the mosaic of communities on Tanganyika’s shores. Stanley records discussions about the uncertain hydrography of Central Africa—how rivers and lakes might interconnect—and the practical implications for travel and supply. He also notes the presence of slave and ivory routes, situating his mission within broader regional economies. The narrative emphasizes cooperative exchange of information, maps, and observations, while carefully separating what was witnessed from what remained conjectural at the time.

As plans turn toward reporting outcomes, Stanley details the logistics of securing stores, organizing escorts, and safeguarding notes. He considers obligations to his employers and to the people who aided his progress, and he addresses responsibilities toward the fellow European traveler he has located, including the provisioning needed for continued inland work. The return path, though more swiftly told, reiterates the themes of risk management, negotiation, and the constant need to corroborate news against terrain and time. The focus remains on delivery of verified information rather than on dramatic flourish.

Taken as a whole, How I Found Livingstone presents exploration as a discipline of documentation: assembling facts from layered testimony, testing them against geography, and building a narrative that can withstand public scrutiny. It preserves a detailed view of East African caravan systems and frontier politics while reflecting the era’s assumptions and limits. Beyond the immediate story of a celebrated search, the book endures as a primary source on nineteenth-century travel, journalism, and cross-cultural negotiation, illustrating how media ambition, local expertise, and sheer persistence combined to shape global understanding of an inland world then largely unknown to European readers.

Historical Context

Published in 1872, Henry Morton Stanley’s How I Found Livingstone recounts an American-funded journey into East and Central Africa undertaken in 1871. The narrative belongs to a mid-nineteenth‑century surge in European geographic inquiry, promoted by the Royal Geographical Society and fueled by earlier expeditions by Richard Burton, John Hanning Speke, and James Grant. At stake were unresolved questions about the interlinked lakes of the interior and the ultimate sources of the Nile. The setting spans coastal Zanzibar to inland caravan routes, where African trading networks structured movement and authority, while European powers maintained consulates and limited coastal influence but little direct control inland.

David Livingstone, a Scottish missionary and explorer, had gained fame for traversing southern Africa in the 1850s and for advocating the suppression of the slave trade through “commerce and Christianity.” After an 1858–64 Zambezi expedition, he launched a final venture from Zanzibar in 1866 to investigate East-Central African waterways and the Nile question. Irregular communications, illness, and the region’s vast distances cut him off from reliable contact by 1867–70, prompting conflicting reports in Europe and the United States. Learned societies, newspapers, and the British public followed his fate closely, intertwining humanitarian concern with scientific curiosity and imperial interest.

In 1869 James Gordon Bennett Jr., editor of the New York Herald, commissioned the journalist Henry M. Stanley to search for Livingstone and report exclusively for the paper. The assignment reflected the era’s expanding mass-circulation press and transatlantic competition for news, where exploration could be staged as both public service and headline spectacle. Telegraph networks and steamship routes accelerated dissemination, enabling readers to follow distant expeditions with unprecedented immediacy. Stanley’s background as a war correspondent and his access to newspaper financing shaped the expedition’s logistics, priorities, and narrative framing, aligning field decisions with the demands of timed, vivid reportage.

Zanzibar, then under the Omani sultan Barghash bin Said, served as the principal staging ground for inland journeys. Its harbor, customs, and merchant houses supplied cloth, beads, and firearms used as trade goods and wages along caravan routes. From nearby coastal towns such as Bagamoyo, caravans moved toward the interior. European and American consulates on the island, including the British consulate led by John Kirk, functioned as diplomatic and logistical hubs, issuing letters, advice, and introductions. This institutional setting anchored Stanley’s preparations and connected his enterprise to existing commercial circuits, local authorities, and long-established Swahili-speaking networks that linked coast and interior.

Inland travel relied on African expertise. Caravans employed porters and guides from communities such as the Nyamwezi, and interpreters communicated in Kiswahili, the region’s lingua franca. Among the most notable intermediaries was Sidi Mubarak Bombay, who had guided earlier expeditions and contributed to routefinding and negotiations. Trading centers like Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika, first reached by Burton in 1858, connected lake traffic to overland routes and hosted mixed communities of African, Arab, and coastal merchants. The same corridors carried ivory and, tragically, enslaved people, whose movement and treatment were recorded by missionaries, officials, and travelers, including Livingstone and Stanley.

Expeditions faced environmental and logistical challenges that shaped their tempo and risk. Seasonal rains, swamps, and steep escarpments slowed travel, while malaria, dysentery, and other fevers threatened personnel. Quinine was carried as a prophylactic and remedy, though its effectiveness varied. Pack animals were limited by tsetse belts, making human porterage essential. Navigating large lakes and rivers required canoes or collapsible boats, and mapping relied on sextants, chronometers, and estimated distances. Such conditions affected the accuracy of earlier maps and fueled disputes over lake connections and river outlets—controversies that framed both Livingstone’s quest and Stanley’s reporting to readers abroad.

The book’s timeframe coincided with intensifying abolitionist pressure on the East African slave trade. The Royal Navy policed the Indian Ocean, and British officials in Zanzibar negotiated restrictions that culminated in the 1873 treaty banning slave markets and the maritime export trade from the sultan’s dominions. Livingstone’s dispatches had described slave caravans and violence in the interior; Stanley’s account disseminated similar observations to a wide readership. These reports strengthened humanitarian arguments in Britain and the United States while intersecting with commercial ambitions, encouraging future schemes for “legitimate” trade and missionary expansion that would influence later imperial ventures in the region.