Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arena Sport

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

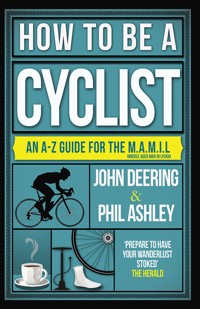

No bicycle repair was ever made easier by turning your bike upside down. White shorts are for other people. A helmet perched on the back of your head is perfect if you ride your bike backwards - These and a host of other handy pointers jostle for attention within this A - Z guide to being a cyclist. It's an essential manual and source of wisdom for those who would be kings of the road. Many pitfalls await the unwary middle-aged-man-in-Lycra, but fear not, for the Guide is here to steer you through choppy waters. No more passing out halfway up a hill. No more ridicule in the work place. No more hurty knee. And no more sock crimes. Pearls of wisdom are scattered throughout this book like rose petals before a princess on her wedding day. For instance, who could deny that life is too short to drink bad coffee? That a noisy bike is marginally more annoying than a whiney toddler? Or that style should ever be sacrificed for speed? Written by experts who know everything there is to know about cycling, yet never forget that there is nothing funnier than a rabbit playing a trumpet, How to be a Cyclist is mandatory reading for all bike riders.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 184

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HOW TO BE A

CYCLIST

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Arena Sport, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.arenasportbooks.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 90971 515 8

eBook ISBN 978 0 85790 803 2

Copyright © John Deering and Phil Ashley, 2014

The right of John Deering and Phil Ashley to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

The authors have made every effort to clear all copyright permissions, but where this has not been possible and amendments are required, the publisher will be pleased to make any necessary arrangements at the earliest opportunity.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

All photography by philashley.com, and the following contributors: Phil Ashley author picture Dan Tsantilis; 40, 106 John Deering; 164 Mondadori/Getty Images; 165 Doug Pensinger/Getty Images; 167 Procycling Magazine/Getty Images; 220 Emily Ashley.

Layout and Cover design by Jane Ashley

Printed and bound in India

John Deering’s first book, Team on the Run, was a study of his time with the chaotic but charismatic Linda McCartney Cycling Team and went on to be voted fifth best cycling book of all time. He followed that with Bradley Wiggins: Tour de Force and he spent much of 2013 working with British cycling legend Sean Yates on his autobiography, It’s all about The Bike, shortlisted for Cycling Book of the Year. John first worked with Phil Ashley on their acclaimed 12 Months in the Saddle. He has supplied many features to publications such as Procycling, The Official Tour de France Guide and Ride Cycling Review, and contributed regularly to Eurosport’s cycling coverage. Cycling and cycling writing has taken him round the world, but he prefers the mean streets of south west London to anywhere else. He lives in Richmond with his Giant Defy Advanced.

Phil Ashley has followed a life in photography. After studying in Hertfordshire and Swansea, he returned to London to spend his younger years working in the studios of many leading lights of the art. At just 25 he set up his own studio and has spent many of the intervening years photographing people, products and places for the likes of the Observer, Nokia, GlaxoSmithKline and Getty Images. Phil’s first bike was a Raleigh Record Sprint, to the envy of his schoolfriends. He turned away from cycling in his teens after destroying an unknown family’s picnic when taking the wrong route down Box Hill. His conversion to the delights of road cycling in the early part of the twenty-first century is accompanied by an uncommon zeal and he weighs considerably less than he used to. He lives in Middlesex with his wife and daughter.

HOW TO BE A CYCLIST

Welcome, Pilgrim. Enter. Relax. You have travelled far, you who would seek wisdom?

Near Guildford.

Ah, Guildford. Gateway to the provinces. Here, have a coffee. Black coffee. And what do you think you’re doing with that sugar?

Oh, sorry. No sugar?

It needs to be earned, Pilgrim. Here endeth the first lesson. No charge for that one.

Well, that’s very kind of you I must say, Mr—?

No misters round here. I am The Guide.

OK. Thanks, The Guide, I’m . . .

I know who you are. You are Pilgrim. But I like your face, son, so I’m going to let you skip the definite article. Now, in your own words, Pilgrim, tell me why you think you’re here.

Umm . . . to get better at cycling?

Right. Well, that will be one of the benefits of coming under my tutelage, but that’s a bit like saying that Gareth Bale joined Real Madrid to improve his Spanish. It’ll happen, but there is a slightly wider perspective.

Wider?

Indeed, Pilgrim, as broad as the deep blue sea itself. You are here to begin your journey upon the road to knowledge, power and true enlightenment. Invincible health, devastating erudition, unimaginable wealth and prowess with the ladies are all there for the taking, providing you listen to me and follow my instructions with care and deference.

Wow.

Well might you ‘Wow’, Pilgrim. I’m not fucking about with the little stuff here, son.

The ladies, you say?

Indeed, Pilgrim. One of the things I already know about you is that you’re absolutely hopeless at understanding the fairer sex.

That’s outrageous. How dare you? I’ll have you know that I . . . I . . . Oh, OK, fair enough. But how did you know that?

Never met a cyclist who did have a clue, to be honest. But we can fix that.

But what about the ladies you see riding bikes?

Pilgrim, do you know what a MAMIL is?

Yes. It’s a middle-aged man in Lycra.

That’s right, a middle-aged man in Lycra. Ladies aren’t sad and deluded enough to think that spending the equivalent of a mid-size South American republic’s GDP on carbon fibre, Assos and Castelli will make them better people. Women riding bikes just aren’t as tragic as you. They go bike riding because it’s fun. But for you, Pilgrim – a devotee, an acolyte – it’s so much more, isn’t it? You want to make cycling your life, don’t you?

Yeah, I suppose. What’s Assos?

Ah, so much to learn. Listen carefully, Pilgrim, because this is some important shit: I know how you feel. The Guide has love, affection and deep, deep understanding for the MAMIL. I know what it’s like to wake up at 3 a.m. in a cold sweat thinking that you’ve only done 50km this week and it’s already Thursday. I know how it feels to believe you look like Eddy Merckx then catch a glimpse of yourself in a shop window and find out it’s a lot more Eddie the Eagle. Yes, Pilgrim, you may well sigh and nod. But, equally, I know what it feels like to sit in the pub waiting for your Sunday roast surrounded by bleary-eyed Observer readers who’ve just rolled out of bed when you’ve already ridden the Horseshoe Pass that morning. You want that, don’t you, Pilgrim?

Yes! Yes, I want that!

But you’re scared, aren’t you, Pilgrim? Blundering around this arcane world of tubular tyres, Roubaix Lycra and gear ratios. There’s a whole new lexicography waiting to trip up the unwary. There are more pitfalls than a bank holiday Total Wipeout Celebrity Special. It’s like Dangerous Liaisons but without a Pfeiffer.

It’s just so frightening.

I know, I know, Pilgrim. Take my hand. I shall be your guide. But beware, for the way of the Guide, to paraphrase the King James Bible, is bloody hard. I eschew frippery. I turn my back on big nights out. I say ‘No!’ to takeaway pizza. Sometimes. I choose a good night’s sleep and five hours in the drizzle around Kent instead. I feel your pain and I share your joy, Pilgrim. Are you ready?

Yes! Help me, Guide!

Hmm. Tell you what, I’ll see what I can do.

Hello, are you the Guide? I could do with some guidance.

Contents

A

Attitude

B

Bike

C

Café

D

Drugs

E

Etiquette

F

Fit

G

Gears

H

Hills

I

Italiano

J

Job

K

Kit

L

Legs

M

Mileage

N

No

O

Objectives

P

Peloton

Q

Quackery

R

Racing

S

Socks

T

Technology

U

Unlucky

V

Vulcanised

W

Winter

X

Existentialism

Y

Yarns

Z

Zeitgeist

Take a deep breath. Fill those lungs. Feel the spring sunshine tickling the four inches of bare shaved skin between the top of your mid-length socks and the bottom of your Swiss Lycra knee warmers. Check your speed on the Garmin. In kilometres, not miles. You are a pro. These are the hours of preparation for the big one. This is the time for you to measure yourself against your rivals. Hold that tummy in. Remember: got to be back by one to pick up the wife’s mother.

So, let me ask you a question, Pilgrim: do you ride a bike for money?

Money? Err, no, not for money. For fun, I suppose.

Working upon the premise that if we’re not doing something for money then we’re doing it for fun, then you are, to a degree, correct. However, there will be many, many seconds, minutes, hours, days and weeks when it is no fun whatsoever.

Forgive the impertinence, Guide, but if it’s not for fun, what is it for?

Just because cycling is not your profession, doesn’t mean we can’t approach it in a professional manner. Be a professional at all times. To answer your question, your goal is something much deeper, much more emphatic than simple fun, Pilgrim. Your hours in the saddle are designed to bring you closer to karma, to true understanding of this world we share. You are here to become a better person. A better word than fun would be enjoyment. Concentrate on a deep, satisfied state of enjoyment, and then, maybe, you can have fun. Because, as you suggested earlier, it is meant to be fun. Eventually.

A cycling cap older than your teeth. Respect.

Oh right. OK then. Where do I start?

Inside yourself, Pilgrim. Inside your head, your heart, your very soul. I am going to prepare you, immerse you in the cooling waters of knowledge. Ready?

Is it cold? Should I have bought a rain jacket?

Oh dear, I can see I’m going to have to be a lot more literal with you. Have you heard of Eros Poli, Pilgrim?

Hmm. Eros . . . Eros . . . Anything to do with Piccadilly Circus?

Yeah. No. No, not really. Eros Poli was the six foot four, 85kg Italian rouleur who took the most brilliant individual stage win in Tour de France history. OK, there are some great stories about the stars and their exploits, but the key thing about Eros is that he wasn’t a star. He was a worker, a domestique, a gregario. Now, the night of Sunday, 17 July 1994 was a very long one for our Eros, as it was the hottest night of the year, he was marooned in a hotel in the south of France and he still had a week left in the longest, hottest Tour in memory. He’d already spent the best part of 300km in long breaks, trying to take something home from a race that had been marked by the absence of his leader, Mario Cipollini, through injury. In fact, way back in the seventh stage, he had spent over 100 miles on his own trying to get a win, only to get caught within sniffing distance of the finish.

Gutted.

You’d think so, eh? On this night, it was so hot that his roommate had dragged his duvet out on to the balcony and was sleeping out there. But the heat wasn’t the only thing on Eros’s mind, Pilgrim: it was the World Cup final that night.

Oh yeah! 1994. That was California, Brazil versus Italy, wasn’t it?

It was. The time difference meant that the game went on late into the French night; and extra time and penalties didn’t help.

The grim winter miles will all be worthwhile when you finally feel that sunshine on your white calves.

Box Hill. Piccadilly Circus for cyclists.

Jesus, how must he have felt when Baggio put his penalty over the bar?

I think we’re back with gutted. Want to know what Eros did? He got up a couple of hours later, drank a lot of coffee, then went on a lone break again. Not any old break, either. It was 231km over Mont Ventoux, one of the most feared mountains in cycling, and it was about 40 degrees.

Wait a second. Ventoux? Didn’t you say he was six foot four and 85kg? That’s the size of two Marco Pantanis. How did he do it?

By riding so hard to get to the foot of the climb that he was twenty minutes in front.

My God. How far in front was he at the top?

Four minutes, with 40km left to go. No bother for our boy. But what I want to tell you about Eros is his advice for you when you’re trying to overcome the odds and they’re stacked against you, when you’re sweating, grunting, trying and failing to conquer a huge mountain that stands between you and reaching your goal.

I’m listening. What does Eros say?

He says: this is a beautiful place. You’re not sitting behind a desk. Enjoy yourself.

That’s some attitude.

The Guide agrees with you, Pilgrim. Come with me and we shall follow the path of Eros. Actually, on second thoughts, that sounds a bit weird. Let’s just get on with it. Let’s start with a checklist to make sure you are correctly prepared.

Go for it, Guide.

Always wear a helmet. Eros may have preferred the wind in his hair, but that was the nineties. It’s the twenty-first century, and you have to wear one if you’re a pro.

Is it acceptable to wear a cap?

A cycling cap is a good thing to carry; you can put it under your lid if it’s pouring with rain, or stick it on at the café. Riding wearing a cap instead of a helmet is really only an option if you live in the thirties or you’re one of those Shoreditch types who waxes his moustache.

Got it. Anything else I need to know about lids?

Yes. The most important thing. Mountain bike helmets have peaks; road bike helmets do not. Take that peak off and discard it immediately. This is one of the things that will immediately differentiate the pro from the IDWID.

I’m sorry, did you say ‘idwid’?

Yes. An acronym for I dunno what I’m doing. Peak on the helmet: you must be an IDWID. Bike upside down for any, any, reason: you must be an IDWID.

Aren’t they easier to fix upside down?

Oh yeah, much easier. That’s why all garages turn cars over before they start work on them. Anyway, that’s enough about IDWIDs for now. Let’s get this helmet right. It needs to be parallel on your head, not on the back of your bonce. If there’s no mirror handy, look up: you should just be able to see the front of it. That’s why you don’t want a peak. If you’ve got your lid on properly and your position on the bike is correct, a peak will stop you seeing where you’re going.

Sorted. Thanks, Guide.

Are you ready, Pilgrim?

As I’ll ever be.

Lord of all you survey.

The Koppenberg can reduce even the best to walking. So this lot have no chance.

In the old days, all the frames were made of steel. They were cheap. Different alloys of steel, of chromium and molybdenum, the Dark Ages really. Then the hard, light, stiff aluminium bikes started arriving: first from America, then Italy and Taiwan. Before long, the directional carbon fibre weaves the manufacturers used for forks to take the sting out of the aluminium were being glued together to make whole frames. The Americans started drawing titanium tubes to tune the ride again. The Taiwanese started making complete moulds for monocoque carbon frames. Over in Europe, the cutting-edge manufacturers found a new material that had outrageous capabilities for bike building: it was strong, light, stiff and absorbent, and could be shaped into a frame custom-tuned for you. It was amazingly expensive. It was called steel.

Right then, Pilgrim, let’s talk about bikes. Let’s talk about bikes, baby. Let’s talk about you and me. Let’s talk about all the good things and the bad things that may be.

Bikes! Brilliant, yes! That’s what I’m here for!

Woah, hold your horses there, boy. You’re not here for bikes, you’re here for cycling. An easy mistake to make, granted, but a mistake nonetheless. We all know somebody who talks about compact versus traditional, Campag versus Shimano, steel versus aluminium, Selle Italia versus San Marco, and who hasn’t been on a bike since they were ridden in black and white. Don’t be that man, Pilgrim. The bike is merely the chassis; you are the engine. It’s you we’re here for, not the wheels.

Fair enough. I do like bikes though.

And well you might. Good, aren’t they? Let’s go through a few things.

I’m all ears.

First of all, let’s talk about what bikes are made of, or to be more specific, what bike frames are made of. The bare minimum you need to get you going is a decent aluminium frame. Yes, that’s al-you-min-ee-um, not aloominum. Tell any Americans you pass on the road that there are two I’s in the word. Now, aluminium is great stuff for making bikes. It’s light, it’s stiff, it’s strong, it’s relatively easy to work with, so it makes for a lively, responsive, nippy, inexpensive ride. Unfortunately, the other thing aluminium is really good at is transmitting shock. To combat that, you need to have a carbon fibre fork to soak up a bit of road buzz. That’s a prerequisite.

Take your pick. They’re all good.

Got it: aluminium frames need a carbon fork.

Good. Now, whole frames made out of carbon have been available for about 25 years, but it’s only in the past decade that they’ve reached maturity.

Why’s that? You’d think that if you could make a fork out of the stuff, then a frame would be straightforward.

Two things, really. The first is a matter of understanding the forces that a frame is subjected to. Carbon fibre sheets are directional, so they’re ideal for forks. You can make it laterally very stiff to make the handling true and predictable, but absorbent perpendicularly, to take the sting out of rough roads. Frames are much more complicated; there’s a lot more going on. You need the back end to be stiff to give you value for the effort you’re putting in, you need the front end not to twist when you’re pounding the pedal on one side and pulling on the opposing side of the handlebars, but you want the whole thing to be light and absorbent too. It’s taken them a while to figure that out.

I see. What’s the other thing?

How you put the thing together. The first carbon frames were tubes, glued into lugs, not that different to welded metal frames. In fact, the lugs were metal on the older ones. The benefit was that they were easy to make and you could tune the size easily by cutting the tubes to length, but they were relatively heavy and a lot of the absorbency was lost with all those joints. These days, the ultimate is to have what they call a monocoque frame, where a mould is made for the whole thing. That’s financially prohibitive though, so there’s a balancing act between cost and delivery. The best off-the-peg bikes are usually two or three pieces put together.

Ain’t about the cha-ching, ain’t about the ba-bling, forget about the price tag.

You can get really cheap carbon frames now, can’t you?

Yes, but be careful. Not all carbon is the same. There are as many different types as there are metals. You can spend a grand on a carbon bike, or three grand on a frame alone. Logic should tell you they’re not the same thing.

OK. Buyer beware. Are all the professionals riding carbon?

The vast majority, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re the best bikes. Bike manufacturers put a lot of cash into teams and they expect them to ride the things they’re trying to sell, and that, largely, means carbon fibre bikes.

What else is there?

Well, one of the drawbacks of carbon fibre frames is the difficulty in providing a made-to-measure bike because a mould is so expensive. Titanium has been the dream material for a long time, but it’s now found a niche as the ideal stuff for making custom frames out of. Ti bikes, like carbon ones, chase the Holy Grail combination of low weight, stiffness, comfort and strength.

Carbon fibre won’t rust.

You don’t need to own all the right tools. You need to know somebody who does, though.

The trouble is, they cost loads; but if you want a custom fit, it’s straightforward to weld one to your shape, rather than knocking up an expensive mould. The other advantage of ti is that it doesn’t deteriorate. It ought to be the same in twenty years’ time, providing you don’t ride it into a brick wall.

Were you saying something about steel earlier?

Ah, the old favourite. If you want a bit of class, a bit of personality, it’s hard to beat. And they’ve got better at it. The best steel is light and stiff, and it’s always been the most comfortable ride. But the real joy is in the personal touch. The relationship between builder and rider is a beautiful thing.

I like the idea of having something with a bit of history behind it.

Remember this: good steel or aluminium bikes come from Europe. Mainly England and Italy. The best carbon comes out of Taiwan. Some people get upset when they hear that their prestigious Italian marque carbon fibre bike was actually fabricated in the Far East, but they’re wrong. The carbon bike industry in Europe is nascent to say the least. It’s a good thing that it’s made out there. As for titanium, the Americans rock.

So much to think about, Guide.

Sweet dreams, Pilgrim.

The Weald from Firle Beacon, a high spot of the South Downs ridge.

Please, don’t let us stop at the café at the top of the hill today.

Please let us wait until we get near home.

I don’t want to get there red-faced and out of puff in front of all those skinny guys again. Please.

Now then, Pilgrim, let us discuss the trials and tribulations of café culture. The dos and don’ts. The opportunities and the pitfalls.

I love cafés, me. You can’t beat a bacon butty, can you?

Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear. Pilgrim, what are we going to do with you?

What?

I was hoping that incident with the coffee might have given you some kind of grounding.

I can only drink black coffee without sugar?

Before a ride or when you’re not riding, that is correct, Pilgrim. But, on the post-ride stop, you can treat yourself to a cappuccino. You can even sprinkle a bit of chocolate on it. Fuck it, scatter three grains of brown sugar on the foam; you’ve earned it.

Can I have that bacon butty now?