Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

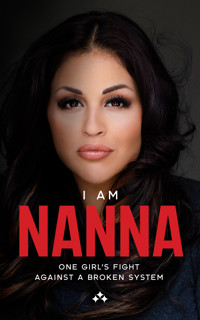

- Herausgeber: Aniara

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

I Am Nanna is a devastating exposé of a system meant to protect—but which destroys instead. Nanna should have been safe. Placed in foster care as a child, she endured years of abuse and sexual assault whilst overburdened social workers turned a blind eye to her suffering. When Nanna finally found the courage to speak out, those meant to safeguard her dismissed her allegations. She had an overactive imagination, they said. She was attention-seeking. She needed to learn to live with it—even as she lived in daily terror of encountering her rapist. Only when her sister broke her silence did authorities act. But the nightmare wasn't over. Moved to what seemed a promising new placement, Nanna was instead abandoned to isolation and despair. A searing indictment of institutional failure and a powerful testament to survival, I Am Nanna asks urgent questions about who we trust to protect our most vulnerable—and what happens when that trust is shattered.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 382

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

I am Nanna

One girl’s fight against a broken system

Nanna Hansen

© Nanna Hansen & Birgitte Vestermark, 2021

Aniara, 2025

Translation by Aniara

www.aniara.one

Original title: Jeg er Nanna: Gemt væk og svigtet af det danske system

Originally published by Grønningen, 2021

All rights reserved.

No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher or author, except as permitted by EU copyright law.

ISBN print: 978-91-90020-78-4

ISBN e-book: 978-91-90020-77-7

Cover photo: Les Kaner

Contents

Prologue

1. The Relocation

2. The Promise

3. The Seven

4. Mia

5. Mathias

6. Vendebo

7. The Girls Gang

8. Buller

9. Escaping

10. Tystoftegård

11. Startskuddet In Orup

12. Faxe Ladeplads

13. Christian

14. Turbulent Times

15. Back To Turkey

16. The Trial

17. Cecilie’s Betrayal

18. Family Honor

19. Department Masnedø

20. Thailand

21. The Money Trail

22. Niki

23. Education

24. Lyngby

25. Homeless

26. Citizenship

27. The Turning Point

28. Institution Nomad

29. Justice

30. My Father’s Shadow

Nanna’s Thanks

Birgitte’s Thanks

Prologue

On December 26, 2014, Randa Nail Abu Hassna ceased to exist. It was ice-cold, one of those rare days when the temperature never rose above the freezing point. Pale sunrays shone over the landscape, but lacked the strength to warm anything at all.

There was not much drama surrounding young Randa Nail Abu Hassna’s disappearance. The police were not involved, no one searched for her in the country’s emergency rooms and hospitals, or reported her missing through Interpol. This stateless Palestinian girl, who had cost Danish taxpayers several million kroner in out-of-home placements, case worker hours, court cases, and compensation, slipped from the public records with a click and a checkmark: An email arrived in my digital mailbox, and a health insurance card found its way to the letterbox of my boyfriend at the time. The name Nanna Hansen was embossed on it. I ran my fingers over the raised letters and felt an exhilarating sensation spread throughout my body.

Nanna.

The name Nanna had come to me several years earlier. One day, I ran away to Odense with some other kids in care, to see if anything fun was going on. We were walking down the pedestrian street, checking for anything worth stealing from the shops. While we were having a look, a woman suddenly stopped and called out to her little daughter. The girl’s name was Nanna. And when the woman called “Nanna,” I answered “yes.” I don’t know why – it just felt natural. The others laughed and thought it was funny that I had responded to her call, but that was the first time the name Nanna stuck in my consciousness.

Now it was on my brand-new health insurance card. After Nanna came “Hansen.”

It couldn’t get more Danish than that. Now I was just one of many – a Nanna among other Nannas. Finally. Finally I fit in. And not only that – I would also be much harder to track down. Relief washed over me, and the fear that had followed me for years now began to dissolve and slowly fade away. Maybe I could at last feel just a bit safer. Maybe I could stop trying to run from the past. From the present. From myself.

I placed the health insurance card in my wallet. This was the beginning of a new era. A new life.

Randa Hassna was forever in the past. A past I closed the door on.

It wasn’t until several years later that I finally found the strength within to open that door slightly. But it’s not possible with a past like mine. The moment I pressed down on the handle and allowed a sliver of darkness to appear, the door flew open, and the ghosts of my past leapt out from their hiding places. They came tumbling toward me, forcing their way through the doorway, demanding to be heard. There are no half-measures in my life. I had to go all-in.

The Relocation

The moment I spotted the flags in front of the plant nursery, I knew where I was. They stood there, three in a row, shining a piercing green toward me, fluttering cheerfully in the light summer breeze. A welcome greeting from hell.

The dark blue Ford Transit turned into the courtyard, and the dark gravel crunched under its tyres when it glided between the low white buildings, turned slightly to the right, and stopped.

I looked around, feeling both curious and uneasy. Behind me and on both sides, a three-winged building enclosed the courtyard. And directly in front of me rose a two-story main house. The buildings were old, but it was evident that they had recently been renovated. The walls were blindingly white and tried to outshine the main house’s glazed black tile roof.

The male youth care worker, sitting in the front passenger seat, turned slightly and looked at me.

“So this is Tystoftegård,” he said. “This is where you’ll be living.” My first thought was: They couldn’t be serious, but I knew full well they could be – and that was exactly what they were.

I also knew that just a kilometre from here lived the man who for several years had abused me. It was terrifyingly close. The moment I stepped outside the courtyard, I risked running into him. It could happen by chance at the local supermarket, at the bus stop, or anywhere nearby.

I couldn’t stay here.

Bring your things, I’ll show you to your room. The youth worker’s voice barely penetrated my consciousness, as if someone had stuffed cotton in his mouth to muffle the sound.

I picked up my shoulder bag from the back seat and pushed open the door. Placed one boot-clad foot onto the black gravel of the courtyard. Let the other follow. Did what was expected of me. Don’t think. Not about tomorrow, not about anything. Just focus on covering the distance from the car to the steps leading up to the main entrance. It’s not certain I’ll run into him. He probably doesn’t even know I’m here. If I can just make it to the front door, I can stay inside and never show my face outside again. It will be fine. One foot at a time. The gravel crunched beneath my soles.

The main house had two entrances. One in the middle and one to the left. We took the left one and walked up a wide stone staircase. Just inside the front door, a lye-treated wooden staircase led up to the first floor. A chemical smell of paint hung between the pure white walls. The stairs ended at a small landing that opened into an enormous white-painted room with a ceiling that rose to the ridge beam, exposed rafters and supporting pillars that seemed to divide the room into three sections across its width. To my left, in the front third of the room, stood a double bed pushed against the wall, surrounded by low bookcases.

“You can unpack your things over there,” the youth worker said, pointing. I went in and set down the bags containing my few possessions.

He walked further into the room and crossed to the opposite side, where a narrow bed stood, partially hidden behind a pillar. He put down his bag and began emptying it.

I glared at his back and hated him with all my heart.

Four weeks earlier, he and his colleague, along with a young woman, had arrived at the institution where I was living. I had run away – again. This time to Holbæk, but Maria, who was my contact person and favourite youth worker, had called me to convince me to come back. Slagelse Municipality had finally agreed to move me from the institution to a place better suited for me, she had said. A place where I could develop and have a normal life. A place where there would be room for me to have my own horse and continue riding. That’s why I came back and met the three unfamiliar staff members. I was actually excited about it, even though I felt anxious. Especially at the thought of having to say goodbye to Maria.

How bad it would get, I couldn’t even begin to imagine when I returned from my escape that afternoon.

“Well, there you are,” was the first thing the unfamiliar youth worker said when he spotted me. I glanced skeptically at him and his two colleagues. They were standing in the hallway just inside the door of the institution where I was living. None of them made any attempt to introduce themselves.

“Go upstairs and pack your things. You’re coming with us,” he added in a commanding tone. I looked at him. He was tall and broad-shouldered and didn’t look particularly friendly. His face was closed off, with a grim set to his mouth. His colleague was equally uninspiring of trust. They looked more like nightclub bouncers than social workers.

I instinctively disliked him, and my desire to leave the familiar institution plummeted right on the spot.

“I’m not going anywhere.” The ice in my voice was unmistakable. He’s not going to fucking order me around, I thought, shooting him a contemptuous look.

“You’re going upstairs to pack, and you’re doing it right now.” The staff member grabbed my upper arm and tried to force me up the stairs. I kicked him in the shin, scratched his arm, and tried to bite his hand to make him release his grip, but it made no difference. His colleague came to his aid, and suddenly I was on the floor with both workers on top of me. They twisted my arms tightly behind my back, and I felt a knee pressing down on my spine, forcing me against the cold tile floor. It was difficult to breathe in that position, and panic washed over me.

“Help me, Maria, help me,” I screamed desperately. Tears welled up in my eyes as I twisted and turned, trying to wrench myself free from their iron grip. I started hyperventilating. Snot and tears streamed down my face. In all my time at the institution, I had never been subjected to a single physical restraint. It hadn’t been necessary because I never became physically violent. Yes, I would get angry and shout insults at people, but I wasn’t a danger to myself or others.

“Is this really necessary?” Maria asked, shocked. “The girl is just nervous about having to leave behind everything she knows.”

The two male staff members didn’t respond. Maria knelt down. She stroked my hair soothingly while the two men continued to press me down against the tile floor.

“It’ll be over faster if you calm down,” said the woman who had arrived with them. But I couldn’t calm down. I could barely breathe, and I was completely panicked. Helpless in the truest sense of the word. While Maria tried to calm me with her familiar hoarse voice, I felt zip ties being tightened around my wrists as the two men yanked me up.

“Will you pack up her things, Michella,” one of them asked, before they dragged me out to a waiting car and threw me into the back seat. I was sobbing so hard I could barely breathe.

Minutes later, I was being driven away from the institution, from Maria, from Ringsted and from everything I had known for the last four years of my life. Heading toward a summer house on Møn. With three people I didn’t know and who I felt meant me no good.

“Just forget about running. It’s not going to happen because we’ll be keeping constant watch over you,” said the one they called Michella. I hated her too. Sydsjælland rushed past in a blur of tears, but with my hands tied behind my back, I couldn’t wipe them away.

We spent four weeks in the summer house before they found Tystoftegård, and they actually did watch me around the clock, as if I were a dangerous criminal or a threat to myself or others. In reality, I was just a deeply angry and unhappy fourteen-year-old carrying a horrible secret.

And so here I was at Tystoftegård. I lay in the darkness, staring up at the scraped wooden beams that were barely visible in the shadows. The moon’s pale light filtered through the three windows in the gable. They hung in a row – one above the other, and I lay so I could look out through them. It felt nice. Liberating, with a view of an endless sky and myriads of stars, both large and small, some bright and sharply defined against the night sky, others more diffuse or so faint they were barely visible. I chose a brightly shining star that sat slightly apart from the others, imagining it was my mother watching over me from her place in heaven. A small glimmer of light in infinite darkness.

A few meters away, the care worker turned in his bed. It creaked under his weight. I froze and stared into the shadows where moonlight couldn’t reach. Was he getting up? Would he come over to me? I strained my ears to track his slightest movement, to be prepared for anything. He rustled a bit more in his bedding, then his breathing became slow and regular. I relaxed. The tension in my neck muscles eased, and my shoulders dropped back into place. False alarm. Fortunately. But I couldn’t handle having an adult man so close to me. I just couldn’t. I had to escape, run away from this place and get as far as I could. Away from the memories, away from the nightmares, and away from myself. But how could I possibly do that when I was under constant surveillance, twenty-four hours a day?

The Promise

For as far back as I can remember, my life has been chaotic and unsafe. I am the second eldest of four Palestinian sisters who were placed in foster care after our father beat our mother to death.

In the years before that, we had been frequent visitors to Copenhagen’s women’s shelters whenever my father’s temper got the better of him. My oldest sister, Jasmin, has been brain-damaged since she was hit in the head by a teapot our father threw, aiming at my mother. I remember sitting on the floor holding her hand while my mother had to push my father out of the apartment. Jasmin’s hand was ice-cold in mine, and while we waited for the ambulance, I promised myself over and over that I would always do as I was told if only she would survive.

While she was in the hospital, the doctors discovered that she suffered from Williams syndrome, a congenital chromosomal disorder. People with this condition have developmental disabilities but typically possess relatively good language skills and are very talkative. Jasmin isn’t like that. Until my mother died, I think I only heard her speak five words, and I’m convinced that her condition was made worse by the teapot being thrown at her head.

Since Jasmin is ill, it has always been my responsibility to look after my sisters, and that was also the last promise my mother demanded of me on the day she was killed.

She knew what awaited her because she had divorced a man who was mentally unstable and violent, and that’s why she explicitly asked me to take care of the other three. I promised her – at the age of five – with eyes dark and round with solemnity, wearing a brand-new orange dress that I had long wished for, but which my mother had said was far too expensive for her to afford. That day I got the dress. And that day I lost my mother and the life I had known until then. If only I could have traded back, I would have done it. A thousand times over. How often I’ve thought that I would gladly go without the orange dress if only I could have my mother back. But of course, it doesn’t work like that.

* * *

The seventeen months following our mother’s death, we lived at Frederiksholm children’s home in Copenhagen’s Sydhavn area. They established a special unit solely dedicated to caring for us four girls. It was an expensive solution that the municipality didn’t want to fund for long. So they began searching for a foster family for us. A middle-aged couple named Gunnar and Lise expressed interest and offered to take in all four of us. They lived on a small farm with their two teenage sons in the village of Magleby, just outside Skælskør. Initially, the staff at Frederiksholm rejected this foster family, arguing that they weren’t qualified to be foster parents for four sisters with our difficulties and needs, but when no one else came forward, we ended up being sent to Gunnar and Lise. Neither of them had professional training in childcare. Gunnar was an electrician, and Lise was a daycare provider. They had fostered children before, and they took us in as a package deal.

The sons were twelve and sixteen years old, and we would become their four little sisters. One big family. The social services were satisfied, and after a so-called transition period, during which we visited Gunnar and Lise a few times and stayed overnight in the yellow house, we moved in with them.

It was February 23, 1999, and it was a Tuesday.

Lise was kind enough during the first few months, but she seemed strangely disinterested in us. She taught us the family’s routines, and we slowly began to adapt, but there weren’t many hugs or loving words hidden beneath her curly, henna-orange hair, which somehow matched – in a slightly unsettling way – her yellow teeth and the heavy amber necklace she always wore around her neck.

Gunnar was a stocky, short-statured man with grey hair, a short beard, and steel-grey eyes. He was friendly and smiling when speaking with other adults, but had an unsettling habit of staring at me and holding my gaze. It was as if he could see right through me.

Our stay with Gunnar and Lise quickly proved not to be the fresh start we were in need of. Just as the mandatory trial period with the foster family ended, and a social worker had placed the decisive checkmark on the form, daily life in the yellow house changed drastically. Now began an endless succession of days filled with hunger, humiliation, and beatings.

This and that were prohibited. First and foremost, we were under no circumstances allowed in each other’s rooms. If one of us, most often my eldest little sister, Sapran, was grounded, she wasn’t allowed to leave the room. For several days, my sister would be ordered to lie in bed facing the wall, and she was only permitted to leave the bed to use the toilet twice per day. Lise would write in her school records that she had been sick, even though it wasn’t the case.

We were absolutely never to touch the mail, and we weren’t permitted to take our schoolbags into our rooms either. They had to remain in the hallway, and we could only take our pencil cases and the books we needed for homework. I didn’t particularly enjoy reading or doing homework, but I was happy to be able to draw.

At dinner time, silence and strict table manners ruled. We girls were told to keep quiet and sit properly with straight backs and arms at our sides. I had protruding front teeth because I’d been slow to give up my pacifier, and my teeth were so crooked that it was easiest for me to chew my food with my front teeth. Lise couldn’t stand it. One day, she sat watching me intently while I ate, and then suddenly said: “You eat like an animal, it’s disgusting. I’d rather have the dogs at the table.”

Her words stung. I was six years old and well aware of my buck teeth. I was embarrassed about them, so she didn’t have to humiliate me like that. Instinctively, I wanted to snap back with something nasty and equally hurtful about Lise’s own nicotine-yellow teeth that looked like they had been thrown into her mouth with a shovel. But I remained silent. I knew better than to talk back. At Lise’s dining table in the kitchen, speaking without being spoken to was not tolerated.

If Lise was dissatisfied with our behaviour, we risked being sent to our room without dinner. Or worse. We risked having her empty our entire plate into the blender, transforming the meal into a sticky mass. It was the most disgusting thing you could imagine. But there was nothing we could do about it. Down it had to go. And if I didn’t eat it voluntarily, she would grip my jaws firmly and force-feed me until the very last spoonful. She might also decide to pour a glass of white wine over my cornflakes at breakfast, making them mushy and sticky, tasting sour and revolting.

The sons were often called down to witness the psychological torture, and somehow it felt worse when there were more witnesses to the humiliations, more eyes resting upon you. But the boys didn’t hold back either when it came to mocking us. I remember standing in the backyard once, where I had been ordered to stand in one specific spot as punishment for something I had done. When the eldest son passed by and saw me standing there, he shouted: “Pull your stomach in, fatty, you look huge standing like that.”

Another time, the youngest son had placed an apple on the edge of the dining table and ordered me to eat it with my oversized teeth while keeping my hands behind my back. It was nearly impossible, and as I tried, he taunted and mocked me.

Gunnar’s temper was terrifying. He didn’t become furious and shout like my father did. His anger was more insidious and unpredictable. It struck like lightning from a clear sky. Overwhelming and sudden.

The first time Gunnar hit me, I was eight years old. It was morning, and he was sitting in his green armchair in the living room watching TV. We girls were sitting on the sofa diagonally behind the armchair, and I had gathered enough courage to speak on behalf of all of us. It was my responsibility. After all,I had promised to take care of my sisters, and none of us liked living with Gunnar and Lise. So I stood up and walked over to stand beside Gunnar’s armchair: “I don’t want to live here anymore,” I said.

Gunnar’s mouth twisted into a sneering grimace, and a small laugh escaped his lips, but he didn’t say anything.

Amal and Sapran stared at me from the sofa, their eyes round with shock and awe. I couldn’t fail them. For their sake, I had to be strong. Without changing my tone of voice, I said: “I don’t think you’re very kind, so I want to leave.”

Gunnar still pretended not to hear me. His only reaction was to turn his chair slightly so I wouldn’t block his view of the TV screen. It really provoked me that he was ignoring me. So I raised my voice a little and continued: “I want to go back to the children’s home, because you’re not very nice to us.”

Quick as a striking cobra, Gunnar’s arm shot out, seized my upper arm in a brutal grip and threw me across his knees. He gave me three hard slaps on my bottom before shoving me to the floor. It all happened so fast that I couldn’t process it until I was already lying there. Then the pain and humiliation hit me full force, and I let out a howl.

Gunnar still didn’t say a word. He had sunk back into his armchair and was utterly focused on the TV program. His face was completely expressionless. It was terrifying.

After that episode, I became more combative. I imagined that if I made myself absolutely impossible to deal with, Gunnar and Lise would eventually give up on having us as foster children, contact the municipality and tell them they couldn’t take it anymore. Often, when I was grounded, I would sit by the window in my room, looking out into the garden, imagining Gunnar with the phone to his ear, using that ingratiating, friendly voice he often put on for other adults, saying: “It’s just not working out, unfortunately! You’ll have to take the four girls back, because we simply can’t manage them here at the farm.”

But it didn’t turn out that way. Instead, the punishment became more rough and calculated. Gunnar was a master at hitting without leaving visible marks on the skin. He rarely struck us in the face, but would often appear unexpectedly behind Sapran and me in particular, delivering a stinging slap to the back of our heads or hammering his clenched index finger knuckle into our scalps. It hurt a lot. And the element of surprise in the punishment left us with an ongoing sense of uncertainty. We never knew when Gunnar would suddenly pop up like a jack-in-the-box and drive his knuckle into the back of our heads.

He would sometimes kick us from behind with his ankle.

Later came the abuse and those long nights in darkness, where I lay listening for his footsteps on the stairs or heard the echo of his threats ringing in my ears. Threats that he would hurt my sisters if I ever told anyone what he did to me when he came into my room at night.

I had to make myself hard, had to avoid crying or showing any sign of weakness at all costs, because my sisters’ fate depended on me. I had to protect them at any price, and if this was the price, then I would have to endure and suffer in silence.

Meanwhile, my hatred for Gunnar and Lise grew, and I seized every opportunity to rebel. But the more I protested and defied them, the more they isolated me from my sisters. To this day, I don’t know whether Gunnar and Lise kept me away from the others to punish me, or because they genuinely feared my defiance would spread to the others, leading us all to finally revolt against the abuse we endured in that yellow brick house on Basnæsvej.

Gunnar was a true master of manipulation, and he constantly tried to mess with us psychologically. He would mock us, humiliate us, and turn everything upside down. When I told him I knew very well that hitting children was forbidden, he would look at me with a slightly surprised expression and claim he hadn’t hit anyone at all, even though I could still feel the dull ache in the back of my head from his hard knuckle.

The prohibitions also played a crucial role. By keeping us separated from one another, he could play us against each other and prevent any real solidarity from developing. Whenever one of us was punished, the others were torn between relief at having escaped punishment themselves, shame at being unable to help or comfort the unfortunate one, and fear that they would be next. Each of us felt completely alone against Gunnar, who, like a terrifying supreme power, controlled our lives according to his arbitrary whims.

Even the ban on bringing mail inside helped isolate us from the outside world, and I later discovered that our former caregivers from Frederiksholm children’s home in Sydhavn had faithfully sent us birthday cards and Christmas cards year after year. We just never got to see them. We weren’t allowed to call them either, even though we missed them a lot, especially in the beginning.

“If they missed you too, don’t you think they would call you?” was Gunnar’s sneering response.

He didn’t tell us that he and Lise had explicitly asked our former caregivers not to visit or call, claiming it would cause us girls too much grief and interfere with the foster family’s attempts to build a relationship with us.

I don’t want to go into more detail about our traumatic experiences with Gunnar and Lise, as I have no desire to rip the wounds open, and besides, my sister Sapran has already written extensively about this dark chapter of our lives in her book Cursed Childhood (Forbandede barndom).

I will simply say that several years later, Gunnar was sentenced to five years in prison for sexual abuse, indecent exposure, and daily acts of violence against me and my sisters. He was also permanently barred from working with children under eighteen years of age – both professionally and in connection with recreational activities. Additionally, he was prohibited from ever living in a household with children under eighteen without first obtaining permission from the police.

The District Court of Næstved, which handed down the verdict, emphasised that it was an aggravating circumstance that Gunnar had molested children who were as young as we were, and who were, moreover, placed in his care specifically so he could protect us. The fact that the abuse had taken place over so many years was also considered an aggravating circumstance when determining the sentence.

My story has a different focus than my sister’s. And my message is another. It’s not about the abuse in the foster family, but rather about the betrayal by social workers and supervising authorities that I saw continued in the years after I was moved from the foster family because I was severely unhappy there. About the greed, distrust, and incompetence that I, as a child and youth in care, felt permeated the system. And about a lack of ability or willingness to delve deeper into the problem and try to find the reason why I reacted the way I did.

Instead, I became just another file in the municipal office, growing into meters of shelf space filled with case documents, while responsibility for me and my development was shuffled from desk to desk, from case worker to case worker, or left gathering dust in a municipal filing cabinet month after month.

* * *

When I was ten years old and discovered that the municipality would move me urgently from the foster family because I wasn’t doing well there, I was overjoyed. I thought I had saved my sisters, but as always, there was another side of the coin. As a matter of fact, no one conducted any supervision of my sisters or asked how they were doing. They merely treated the symptoms and moved me because I was reacting with anger and causing trouble. Meanwhile, no one seemed interested in Sapran, who was more timid by nature than me and always tried to please her way out of problems, or in Amal, who still played the role of pet in Gunnar and Lise’s sick psychological power games.

To this day, I don’t know why I was the only one they moved, and I can only guess it was because the municipality couldn’t find a place that could accommodate all of us.

Gunnar was obviously furious about having to let me go. While carrying my belongings out of the house, he spat curses at me.“You’ll regret this, Randa,” he hissed. ”You’ll spend the rest of your life moving from place to place. Someone like you will never have a real home!” I steeled myself. Let his mocking words bounce off my shield.In just a few minutes it would all be over, and we would be picked up by the municipal workers and taken to a better place. But as usual, Gunnar had a trick up his sleeve. Just before the case workers arrived, he dragged us all out into the courtyard and pointed an accusing finger at me.

“Your sister is moving,” he announced, “because she can’t stand living with you anymore!”

I gasped in surprise. That was nowhere near the truth. There was nothing I wanted more than to help my sisters find a better place, but Gunnar made it sound like I didn’t care about them. Now we were being separated, and all our talks about escaping together echoed with broken promises. Gunnar’s presence didn’t even give me the chance to tell them the truth of the matter. Once again, Gunnar had succeeded in bringing me down and sowing doubt and discord between my sisters and me.

The disappointment in their eyes was unbearable. It burned into the back of my neck all the way down the driveway and far along Basnæsvej. I hadn’t saved any of them. I had only saved myself. I had broken my promise to my mother.

The Seven

The Municipality of Slagelse had chosen to place me in a yellow house called The Seven, because it was located at number 7 on Sct. Knudsgade in Ringsted. The institution was part of the Ringsted Children and Youth Centre and housed a few children with serious problems.

I loved The Seven because it was an awesome house. It was small and cosy, and there were only five of us living there, so in a way it felt a bit like a family.

Just as you entered through the front door, a staircase led up to the upper floor, where we each had our own small room. Mine was the farthest from the stairs. It had white walls and a sloping ceiling that faced the garden. Just to the right when you came through the door was a desk. And under the sloping ceiling stood my bed. When I sat at the desk, I could look out over Sct. Knudsgade, and if I turned the office chair, I could look out over the garden.

On the ground floor, the living room and kitchen were one open space. The ceiling was pretty low, and the windows were set low in the walls, as they often are in old houses. The furniture was quite ordinary – exactly what you’d expect to find in any family home.

The house was elegant from the outside. It was Skagen yellow, and between each of the white-painted windows, the facade featured small protrusions that looked like flattened columns. These stretched from the top of the stone foundation all the way up to the red-tiled roof. The entrance door was located in the house’s gable, and to reach it, you had to pass through a small wooden gate in the white-painted fence. Behind the house stretched a rectangular garden with very tall trees, where we eventually built a tree house. It all felt very homey and cosy, and very little like an institution.

* * *

That first evening at The Seven, I was allowed to choose what I wanted for dinner, and I didn’t think twice before saying “beef patty with gravy, potatoes, and caramelised onions.”

The food was placed on the table, and there was plenty of it. This was completely different from what I was used to in the foster family, where we often went to bed hungry. I put a couple of patties on my plate. Then potatoes, poured thick brown gravy over everything, topped it with caramelised onions, and then I started eating. It was fantastic. I’m crazy about potatoes, and these were round and light yellow, not too firm and not too mealy, with a lovely sweet taste. The patties were well-cooked with a thin crust and slightly pink inside. I chewed contentedly while glancing around at the others at the table. The staff and other children were talking quietly together. No one seemed to pay any particular attention to me. It wasn’t that they were ignoring me; they just weren’t staring or keeping watch over me like my foster mother Lise used to do. They let me sit there and take in the atmosphere around the table, look around the dining room, and they let me eat in peace.

After I finished my first portion, I reached for the spatula again and loaded first one, then two, and finally a third beef patty onto my plate, all while keeping a watchful eye on the adults. None of them made any move to stop me. One of them gave a small, crooked smile, but didn’t say anything. I ate again – no, that’s not right – I stuffed myself, and I just kept going and going and going.

When the second portion was consumed, I launched another assault on the serving dishes and pans. Shoveled potatoes onto my plate and transferred more beef patties the same way, while trying to figure out if there were any restrictions in my new home. Apparently, there weren’t. That evening, I managed to eat nine beef patties, fourteen potatoes, and a mountain of caramelised onions without anyone so much as raising an eyebrow. The price I paid was terrible stomach pain throughout the night, which lasted most of the following day.

* * *

The kitchen matron at The Seven was called Anne Marie. She was a warm-hearted, middle-aged woman with broad hips and soft breasts. Her face was furrowed by life, but her dark brown eyes were kind and trustworthy, and looking into them filled me with an immense sense of calm. She was a real mother hen who would offer me toast with butter and cheese or jam, and always looked after me with love. She played a great role in making The Seven feel more like a home than an institution.

There was no doubt that Anne Marie ruled over the kitchen, and she could be incredibly harsh if you didn’t behave properly, as the kitchen definitely wasn’t a playground. But she was also very caring and loving, and I had enormous respect for her. I think the other children at The Seven did too.

I loved being in the kitchen with Anne Marie. She would always chat away while chopping and dicing, and she let me sit there enjoying the scent of food simmering on the stove. For lunch, she would serve me fried potatoes, and I loved it. I still do.

* * *

When I moved into The Seven, at just ten years old, I was the youngest resident there.

But even though I was the youngest, I was by no means the most compliant. I felt very torn when I arrived at The Seven. On one hand, I was relieved to have escaped the foster family, but at the same time, I was extremely worried about my sisters whom I’d had to leave behind. How would those small, defenceless girls manage without me there? I was usually the one who confronted the foster family. It was me who fought back, and me who took the heat. How would they possibly survive when I wasn’t there anymore to act as a lightning rod for Gunnar’s temper and moods? I shuddered. I couldn’t bear to think about it.

I was quick to rage and would lose it over the slightest provocation. Not that I would hit or kick when I got angry. Instead, I used my voice. I shouted, I yelled. I spoke viciously and was cruel to anyone who came too close. I hadn’t told anyone that Gunnar had abused me, neither the staff nor the kids, but if any of the male staff members so much as grabbed my arm, I would completely lose it. I just couldn’t let them touch me!

At the same time, I had a strong need to constantly test the adults’ boundaries. It was as if I had an insatiable urge to act out after my time with the foster family, where I had constantly been walking on eggshells, constantly keeping my guard up. I had been trapped in a cage, suppressed, subject to the family’s whims, locked in my room, and all of a sudden I was free. But I had no idea what to do with all that freedom, and it wasn’t easy for me to navigate it.

I felt an irresistible urge to constantly test how far I could push the adults before they got angry. What would it take before they hit me? To be completely honest, I think the staff struggled to handle a young girl like me who took up so much space in an institution.

When I arrived at The Seven, I didn’t really have any sense of who I was, no idea of my own identity, so I modeled myself after the other residents, and it was a huge surprise for me to discover that there could be so many different types of people like those who lived in the yellow house.

Besides me, there was Natasha, who was around fourteen or fifteen. She was the cool girl at the residential home, the one people looked up to, the one with status. Natasha had long, blonde hair and a rather broad nose. She was a beautiful girl, and guys would circle around her, though back then I didn’t quite understand why. I just sensed that she could control everyone around her and get them to do exactly what she wanted. I don’t think I ever saw her hit anyone or use physical force in any way. She didn’t need to. Natasha had mastery over words, and her verbal humiliations were as sharp as the crack of a whip – and about as painful for those on the receiving end. So nobody wanted to get on her bad side.

Then there was Vibeke. She was a plump girl, but somehow rather colourless. She was just … there. She never had an independent opinion about anything at all. If Natasha believed something, Vibeke believed the same thing. Always. Maybe because it was the safest option.

And then there was Max. Max was a couple of years older than me, and he hated people with different skin colours. He was always after me, and I didn’t really understand why until I met his parents, who, as far as I could tell, were pure racists. Max bullied me, hit me, and gave me dead arms whenever he got the chance. It hurt like crazy when his bent middle finger hammered right into my shoulder muscle, sending a shock through my entire arm and leaving a tingling sensation spreading through my fingers.

At mealtimes, Max would almost daily grab a litre of milk and throw it over me while shouting “Turn white.”

Anders, who was one of the youth workers, told me to just ignore Max, but I couldn’t. I just couldn’t. Instead, I would lose it completely, throwing myself at him, hitting back or spitting and scratching him, and it usually ended with me being the one pressed down against the floor and restrained, or being sent to my room to cool off.

* * *

At The Seven, we got pocket money. This too was an entirely new concept for me. Once a week, I was handed a shiny twenty-kroner coin that I could spend on whatever I wanted. I can still remember the feeling of walking down the pedestrian street in Ringsted, sensing the weight of the coin in my palm. That euphoric feeling of knowing that I – and only I – decided what it would be exchanged for. Should I spend it on sweets? Or maybe a kebab? These were the difficult choices I suddenly faced. I ended up spending the money on sweets.

Just a few weeks later, pocket money lost its effect on me. They were no longer magical coins that had to be handed over the counter to feel real. They could be used for something bigger. Something you really wanted. That is, if you set them aside and saved up.

I had fallen in love with a silver handbag hanging in one of the pedestrian street shop windows. It cost a dizzying one hundred fifty kroner, so I would have to save for many weeks before it could be mine. But I am stubborn and persistent, and when I set my mind to something, I do it. So I gritted my teeth and stayed away from both kebab and sweets, and one day I could proudly walk through the door to The Seven with my (horrible) new silver-shining handbag dangling from my wrist.

The pocket money followed a special municipal rate schedule and increased with age. So did my need to spend it. At some point, I managed to convince the care workers that I was a year older than I actually was. Maybe they fell for it because I’d always been tall for my age. In any case, it would be several years before they discovered my little scam. They just faithfully continued celebrating my thirteenth birthday when I turned twelve, and my fourteenth birthday when I was really turning thirteen. And they kept raising my pocket money to match my supposed age. That way, I quickly ended up with quite a bit more money in my hands than my peers. The trick was only discovered when, at age fourteen, I needed a passport, and someone finally took the time to closely examine my birth certificate.

Fortunately, I didn’t have to pay the money back, but I couldn’t escape having to tell the other children that I was actually younger than I’d been pretending to be. That was almost the worst part. By then, I’d spent ages strutting around, proud of being the oldest at the institution, but after my little scam was discovered, that title was no longer mine.

* * *

When I arrived at The Seven, I had a really weird sense of style. I had no idea what clothes went together. Not like Ida and Karina from The Nine next door, who seemed like they were just born cool. They wore g-strings and tight tops that always managed to show a bit of midriff. Ida always dressed completely in black. Her tight flared pants were black, her crop top was black, and she had a belly button piercing. I was totally fascinated by her.

Karina had a lovely, round face and always wore Miss Sixty jeans, and I thought these girls were simply the coolest in the world. They were a couple of years older than me, and both had dated a guy named René, and now the three of us had ended up in the same home economics group. Quite a love triangle played out among the pots and bowls, as the two older girls saw each other as rivals, while I was just in awe of being in a group with two people I looked up to so much.