Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Legendary British comic actor John Inman broke down many boundaries by playing the camp Mr Humphries in the long-running sitcom Are You Being Served? The show ran for thirteen years, had a spin-off movie and attracted millions of viewers in the UK. Inman's character, whose innuendos were adored by viewers, invariably got the biggest laughs – and this at a time when being gay was largely frowned upon. Away from television, he soon became one of the most in-demand pantomime actors, making a small fortune over several decades. Yet it was as Mr Humphries that he was best loved and the reason he was regarded as a national treasure. In his private life, Inman was secretive about his sexuality until he married his long-term partner Ron Lynch in a civil ceremony in London in 2005. He died two years later following a long battle with hepatitis. Featuring revealing interviews with many of Inman's surviving cast mates and colleagues, I'm Free! uncovers the full story of a man who was adored by millions and who broke down barriers by simply being himself.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 313

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

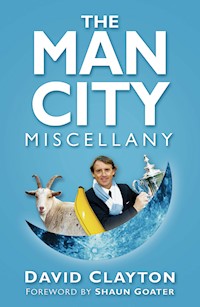

© David Clayton, 2024

The right of David Clayton to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 308 9

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

This book is dedicated to my beautiful wife Sarah and our incredible children, Harry, Jaime and Chrissie.

As the great John Candy once said, ‘Love is not a big enough word.’

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Born to Perform

2 Winging it

3 Salad Days, Indeed

4 Are you Free, Mr Inman?

5 Carry on Camping

6 The Nation’s Favourite

7 Onwards and Upwards

8 Entertaining Mr Inman

9 Opportunity Knocks

10 Troubled Waters?

11 Back to ITV

12 Less is More

13 Menswear!

14 End of an Era or Start of a New One?

15 American Dreams

16 ‘Have You Met My Daughter?’

17 The Return of Claybourne Wilberforce Humphries

18 King Rat

19 The Elder Statesman

20 Dear John

21 Being John Inman

22 Life Without John

23 John Inman: Pioneer or Harmful Stereotype?

24 There’s Nothing Like a Dame

Panto Appearances

Acknowledgements

When you begin any biography, deciding where to start can be a bit of an issue. The usual process, having done your initial background research and created a timeline, is to start contacting agents and trying to trace friends and family – many of whom have no online presence – plus people who have drifted out of the public eye or retired.

I was very lucky writing John Inman’s book in that I ended up with some incredible help from some very special people and, as I went along, the insights provided by one of John’s oldest friends, Peter Richards, became central to everything I did. To get to Peter, I had the wonderful assistance of Doremy Vernon, who is one of the few remaining cast members from Are You Being Served? Doremy helped me open so many doors and her wonderful encouragement and determination to bring me incredible contacts, phone numbers, stories and to share her opinion was above and beyond. I couldn’t have written this book without her.

Later, I was delighted to receive a Facetime call from the wonderful Miriam Margolyes and, in turn, she introduced me to an old friend of John’s, Christine Ozanne, who I would later christen ‘Miss Marple’. Christine gave up her time to interview Peter Richards on my behalf and to field endless questions, and I honestly think this book wouldn’t have been half as detailed without her wonderful assistance. I am deeply indebted.

Paul Mead was another excellent source of early information, but this is just the tip of the iceberg because writing I’m Free has been a real pleasure and it has allowed me to speak with some amazing people. People like Melanie Stace, a former co-host on The Generation Game, who couldn’t do enough to help me, and Susan Belbin, former production manager to David Croft, who gave me a rare interview about her years working with John on the show. Fantastic people with warm, vivid memories of John.

I could fill a chapter thanking everyone – the superb BAFTA-winning actor Jason Watkins gave me time during his hectic schedule to recall playing John Inman in the 2016 tribute show of Are You Being Served? – but the tendrils of this biography literally stretch around the globe, with Australia and the United States featuring prominently.

Tony Hare, one of the BBC’s top comedy scriptwriters, also shared his wonderful memories of working with John

Actress Sherrie Hewson, star of Coronation Street, Benidorm, Loose Women, another star of the 2016 remake of Are You Being Served?, was only too happy to share her memories of John.

Mr Spooner himself, Mike Berry was my very first interview and along the way I also got to speak with John Lloyd, Jeffrey Holland, Barry Creyton, Melvyn Hayes, Bobby Crush, Su Pollard, Jimmy Cricket, Les Dennis, Joanna Lumley, Brian Blessed, Shane Bourne, Gary Wilmot, Joanne Heywood, Rula Lenska, Bill Young, Alex Needham, Niall Gavin, Liam Rudden, Fay Hillier, Peter Symonds, Richard Curtis, Sally Grace, esteemed Australian TV star Christine Amor, Sallyann Webster and many more …

Also, there are the words of the wonderful Mark Gatiss, Times journalist Matthew Parris, plus the help of countless agents – many very helpful, a few not so much! – and the valuable contributions of Alistair Smith of The Stage, Helen Nicholas at the Blackpool Gazette, Paul Middleton, Graham Robson, as well as the fantastic resources and info supplied on pantoarchive.com and theatricalia.com which proved invaluable during my research.

Thanks to John’s friends for providing many of the illustrations. Every attempt was made to track down credits, but any oversights will be corrected in future editions.

Of course, there are people who are ‘invisible’ in many ways, but equally important. Mark Beynon, my long-suffering commissioning editor at The History Press, was as patient as always and is continually supportive of my ideas as deadlines sailed into the rearview mirror. This is the fourth biography I have done with Mark, and I also think it is the best. But then I would say that.

Last but not least, to my wife Sarah and our three kids, Harry, Jaime and Chrissie – the ‘kids’ all being bigger and smarter than I am now – thank you for allowing me to immerse myself in the ‘spare time’ I had outside my day job as a journalist.

Again, thank you so much to everyone for sharing their many memories of John Inman. He was a much-loved man, that’s for sure.

Introduction

I don’t believe in coincidences and think everything that happens has purpose. The first ever episode of Are You Being Served? was screened on my birthday on 8 September 1972, and John Inman was buried on my wedding anniversary on 23 March 2007.

That may seem insignificant to some people, but not to me. Some things just feel written in the stars, don’t they?

I must admit, I was surprised nobody had written a biography of John Inman when I first floated the idea to my editor.

I was a kid when Are You Being Served? was at its height and I always remember laughing and enjoying a show that had a wonderful cast with sharp, witty scripts.

Mr Humphries was hilarious, and even at a very tender age, I knew his character was somehow different. While I might not have understood completely that he was almost certainly gay, he introduced a campness into the living rooms of millions of people and, along with Larry Grayson, proved to be incredibly popular to young and old alike.

It’s easy to forget what a huge star he became in Britain, Australia and the United States. He was also loved in the Netherlands, Canada and many other countries that screened Are You Being Served?

But I was intrigued to find out how this fame came about – was it an overnight success or did he have a long body of work that perhaps not many people knew about that led into it? Plus, what happened to him after the show finally ended its thirteen-year run?

What I discovered in the pages that follow, told through the eyes of close friends and colleagues, is that John Inman was greatly admired and, though he kept his private life private, once he stepped on to a stage, in front of a camera or appeared as a dame in any number of pantos, he was the consummate professional and a wonderful entertainer, hellbent on sending people home happy.

You’ll learn all about that as you go along, and at the end of the book, I speak to a number of journalists, commentators and actors to try to find out whether John Inman forwarded the cause for gay people or did their fight for equality more harm than good. I think it is a fascinating end to the journey, and I thank The Times and The Guardian for permission to use a couple of very powerful articles that appeared after John’s death.

I hope you enjoy John Inman’s life story as much as I did writing it.

David Clayton

Cheshire, January 2024

1

Born to Perform

Some people, they say, are born to perform.

They have an innate desire to entertain others, stand in the spotlight and milk the applause for all it is worth. It’s in their blood and seems to be pre-programmed into their DNA and, no matter what, they will make their dreams become reality by hook or by crook.

Their path to fame and (sometimes) fortune might be full of challenges, obstacles and hurdles, but they find a way, eventually, using a mixture of talent, the odd break here and there, a few white lies and, most of all, because they are driven to find that stage to perform on and that spotlight to stand in.

All of the above is true of Frederick John Inman, who was born on 28 June 1935, at 18 Garden Street, Preston, in Lancashire. It was a modest terraced family home, just a stone’s throw away from the nearby Avenham Park and the River Ribble.

He was Frederick Inman and Mary Rawcliffe’s first child – they would have another son, Geoffrey, a few years later – and he was born into a household of moderate income and occasional domestic abuse. In later years, John would say that his father was ‘a drinking man who used to knock my mother about’ – though understandably, he would never say much more than that.

His parents were both hairdressers – Frederick was a master hairdresser, no less. John’s first few years in Preston were sometimes upsetting as his father took his own frustrations out every now and then on Mary, leaving their son to escape into his own world, one filled with sparkles and wonder.

The first inklings that the Inmans’ first-born might have stars in his eyes came when he began to hold mini concerts in the back garden for friends and family, which would always be a mixture of song and dance. The applause at the end was all he needed to fuel his passion and by the age of 5, he had a number of characters that he had developed, including his showstopper, ‘Bill’.

‘He was always singing and dancing and inventing characters,’ recalled his mother in 1976. ‘One character was called Bill and he’d use his grandfather’s walking cane, go behind the curtain and the door and make his entrance. He’d say, “Bill’s here!” and then start to dance.’

John began his education at Cambridge House School, and it wasn’t long before he’d found a new audience to entertain, inventing sketches with his friends as the Second World War progressed. Preston would escape largely unscathed from the Luftwaffe air raids, though the German bombers would pass high over the town on their way to military targets in Barrow-in-Furness some 70 miles north.

John and pal Peter Diamond would perform shows in Peter’s garage at 214 Brockholes View, creating their own theatre among the various bric-a-brac that was stored there, including their own production of Cinderella. Years later, John would regale the story and add, ‘And no – I wasn’t Cinderella!’

Their first ‘professional’ show was at the New Victoria pub on Church Street in town, and it was perhaps here more than anywhere before that convinced John that his future lay in showbusiness.

He idolised movie star, dancer and entertainer Betty Grable and he had an innate talent to design and create glitzy dresses and costumes for his own performances, often inspired by Grable’s Hollywood glamour. His mother encouraged his artistic leanings, even paying for him to take elocution lessons at a local church to give him a chance of perhaps winning less colloquial roles in the future – something few northern actors and entertainers ever quite seemed to shake off in their bid for national acclaim.

Like any family in Britain at the time, the Inmans suffered during the war with restrictions on movement and rationing causing them to reassess their lives and ambitions to give their sons the upbringing they wanted. So when the conflict ended in September 1945, Frederick and Mary decided they wanted something different. Their marriage had not been without its problems, but Mary was committed to her husband in spite of the beatings she would occasionally suffer.

The country was slowly recovering from almost seven years of conflict and continued shelling from the Nazis and there was a collective hunger and thirst to move forward and enjoy life again. Fortunately, the Inmans didn’t have to look too far to find everything they wanted and more, and for 13-year-old John Inman, it was manna from heaven.

The family moved 17 miles west to Blackpool – a place they’d always loved and frequently visited – and bought a boarding house at 55 Banks Street in the seaside town. Conveniently located just a few hundred yards from Blackpool Talbot Road Railway Station, the Irish Sea was visible at the west end of Banks Street and with the promenade, beaches that stretched for miles and trams making for a bustling, vibrant spectacle.

But what thrilled and delighted the impressionable John more than anything was the fact that Blackpool was the entertainment capital of Britain, with its many theatres and concert halls attracting all the top acts of the era. And he would see them all, saving his pocket money to go and watch some of the biggest acts in vaudeville, soaking it all up with vociferous enthusiasm, none more so than his comedy idol Frank Randle, who was a huge star in the north of England and the man who, more than any other, inspired the teenager to follow his showbusiness dreams.

During an interview for US TV, John would later recall those heady days on the Fylde coast:

All the stars came to Blackpool and Frank Randle was the biggest draw of them all. People would queue for hours to see him. I’d go and see him for one and six in the stalls and he’d come on stage with his boots on the wrong feet and hold the audience in the palm of his hand for as long as he liked – and he succeeded by just being himself.

I saw things like Happidrome with Harry Korris, Cecil Frederick and Robbie Vincent and had been an avid listener to the show on the radio. They were a great trio and very popular who played to packed halls. They were also great favourites of mine.

A few years later there was a show on the North Pier called Lawrence Rides on With the Show featuring Albert Modley, and I went to see him do his act and he was another of my idols.

These were magical, intoxicating days for John.

Now attending Claremont School in Blackpool, he became involved in the theatrical productions and enjoyed creating props, sound effects and other aspects of backstage management. Commenting that one particular sound effect of a character falling in a river sounded more like a ‘sugar lump dropping in a tea cup’, John and friend Tommy DeVere found an old bathtub, filled it to the brim and then dropped a hefty boulder in as they recorded the splash, which also drenched the pair in the process.

‘Now that’s a body falling in water,’ commented John, before turning to his pal and claiming, ‘but you’ve ruined my make-up!’

His penchant for performing and his understanding of theatre meant that when any auditions were advertised – and he scoured for them in the local papers continually – he was well placed to go along and try his luck.

John Inman was no ordinary 13-year-old, and his effeminate voice, openly camp behaviour and light on his feet gait could easily have led to him being bullied by his contemporaries, but his ability to make others laugh was also his best protection and he was a well-liked schoolmate.

He had not been resident in Blackpool for more than a few months when he won a part in a play called Frieda at the South Pier Pavilion, playing the lead’s son and immediately catching the eye with a mature and comedic performance beyond his years. The Jack Rose Repertory Company paid him the not insubstantial sum of £5 per week – the equivalent of £227 in 2024 – to appear in the play and the management were suitably impressed enough to give him part-time work as a general dogsbody, making tea, cleaning up, helping with props and sets after the run in the show ended, and he loved every minute of what was, in effect, his apprenticeship in showbusiness.

John would fill in roles here and there and be continually in and around the various productions, plays and shows, meeting actors, bringing them cups of tea and chatting to them about their craft and learning all the time. He could also watch their performances for free when he wasn’t involved and was also now earning enough to pay admission for whatever entertainer he fancied seeing.

Blackpool was a thriving, energetic place to live with hundreds of thousands of tourists packing out the town’s theatres, concert halls, hotels, boarding houses and bed and breakfasts during the spring and summer months, with the famous Blackpool Illuminations extending the holiday season well into the autumn.

At Claremont School, aged 14, he took on his first starring role in the production of Aladdin, playing the classic pantomime villain Widow Twankey in a costume designed by his own fair hands. His comical performance stole the show and he helped create a ‘boy mangle’ that he would turn and ‘flatten’ out schoolmates as they were sandwiched between two rollers, to the delight of the gathered parents, teachers and fellow pupils. It was his first public display as a pantomime dame and the reaction he received would lead to a love affair with panto that would last all his life.

Within a year, John’s joyous time at Claremont had ended and, aged 15, he left school to seek his fortune. It was 1950 and a whole new set of opportunities lay before him, but first he had to earn his keep.

Given his artistic talents and dressmaking skills, it was perhaps no surprise that he was taken on as a trainee window dresser at Fox’s Department Store on Church Street in the town centre, and there he would be based in the gents’ outfitters department. His boss Jack Holden recalled, ‘He was a jolly good assistant, eager to learn, easy to teach – I was sorry in many ways that I eventually persuaded him to leave and go to London and I’m pleased to say that, having applied for the job I’d suggested, he got it.’

Of that time, John remembered, in an interview from 1976:

I never used to do any work! Jack did it all while I made props in the fitting room! He used to come in and say, ‘There’s a customer here, John,’ and I’d look up and he’d just add ‘Oh, I’ll see to it you just get on with whatever you’re making.’

John still had time to put on a performance of Mother Goose at the local church and brother Geoff recalled how he later felt the sharp edge of his brother’s tongue. He said:

John made the costume by himself, and I had to go into it with a little peephole at the front and when I came on stage his face looked a bit naughty because there was smoke coming out of the gills, which was me having a crafty drag on a Park Drive!

He stayed at Fox’s until he was 18, but his boss felt John was destined for bigger and better things. He had outgrown Blackpool somewhat and Jack Holden told his protégé that he needed to spread his wings and head for the bright lights of London.

When a position at the prestigious Austin Reed flagship store in Regent Street in London was advertised, Holden encouraged John to apply – and, as stated previously, he was successful in his application. It meant uprooting from the north for the first time in his life and at 18, he’d be standing on his own feet without his family around him in a new and much bigger city. He found a £3 per week bedsit and was soon sewing costumes for the many nearby theatres to augment his modest income.

Typically, he took it all in his stride and was soon a popular member of the gents’ outfitters he now worked for. And, much like the future Mr Humphries he would achieve worldwide fame with, he never missed an opportunity to have fun, managing to supress a smile as he stood in the window on one occasion holding a sign that said, ‘Available in other colours’.

One former colleague, Eddie Whitehouse, recalled how quickly John made an impression for both his professionalism and the ability to make anyone and everyone laugh.

‘Each Friday, we’d join all the other members of the department to discuss the week’s work,’ he said:

John was always late for our Friday meetings – always. Anyone else would have got into trouble but not John – he used to breeze into the office with the boss with everyone glaring at him for being late, but he soon had everyone in stitches because he’d say, ‘What’s up? Have I missed the start of a big film?’

His boss, Ron Dyer concurred, adding: ‘It was impossible to lose my temper with John – he was so funny – but he was also very good at his job. But I knew he wouldn’t stay with us long because he told us constantly of his real ambition, which was to go on the stage.’

Indeed, just two years later, the 21-year-old John Inman decided it was now or never and in 1956 he handed in his notice, which the company accepted reluctantly. He’d decided that he had to get a foot on the theatrical ladder somehow and four years of working in a men’s department had not curtailed his dreams of being in showbusiness – if anything, it had fed his hunger even more. Time and tide waited for no man and if the theatre wasn’t going to come to him, he had to find a way to go to it and make things happen, one way or another.

2

Winging It

During his time at Austin Reed, John had become friends with BBC newsreader Kenneth Kendall, who worked alongside him for a short time. Kendall, eleven years older than John, was a freelance newsreader for the BBC and also an actor who was part of a repertory company based in Crewe. Kendall enjoyed John’s company, and he could also see he had a talent that needed a break of some kind, so he offered him a job as part of the company – which John readily accepted. It meant returning north again to live in the Cheshire town, best known for its vast railway junction, but it also meant he was just a relatively short train ride back to Blackpool to see his parents whenever he wanted to.

In 1986, on Mike Craig’s It’s a Funny Old Business show on Radio 2, John recalled:

A mate of mine [Kendall] was taking a Rep company to Crewe, and they didn’t have a scenic artist, so I said, ‘Well I’m a scenic artist so I’ll come and paint the sets.’ I wasn’t, but I had done some set painting, but it wasn’t exactly my job stamp. So I went along and did that for ten weeks in Crewe.

On the second or third week, they were doing an Agatha Christie play – The Spider’s Web – and they didn’t have enough people. So not only did the stage manager get roped in to play a part, so did everyone else, including me – the scenic artist – and I played the part of a 65-year-old Justice of the Peace called Hugo Birch and I got wonderful notices for it!

Being part of the company meant he was immersing himself in the acting world, and he was soon regularly performing in weekly plays at Crewe’s Lyceum Theatre with a group of seven or eight actors. The roles would be varied, but it would enable him to get the one thing he needed most to progress his fledgling career – an Equity card – something no professional actor could find work without.

He spent a few months in Crewe before returning to Blackpool, where his brother Geoff helped him get a job working with his employers – at a gents’ outfitters! It felt as if things had come full circle and he was back working in menswear in Blackpool again, but far from feeling sorry for himself or having his tail between his legs, he knew it was just a temporary bump in the road for his acting career and he continued to perform whenever the chance came, working on a casual basis with his brother and making costumes for the theatres of Blackpool when he wasn’t on stage.

‘That’s how it started,’ said John on his time in Crewe:

and it sort of snowballed from there. I decided I didn’t really like being a scenic artist because it’s a dirty job, so I became a stage manager. And then I started to go from rep company to rep company with chunks of labour exchange in-between. I’d always been a bit nifty with a needle, so I’d make costumes when I wasn’t acting.

But John was always on the lookout for new opportunities, and it wasn’t long before he found a job advert he liked the look of. The Royal Theatre in Chester was looking for a stage manager and his application resulted in an interview with theatre boss Arthur Lane.

Though John had performed all the roles of a stage manager over the past few years, he’d never actually been employed as one, not that he was going to let that stop him. Speaking during a TV interview in 1976, Lane – who had played many small roles himself in films – recalled that job interview with great clarity: ‘I met him, and John said, “I’m the finest stage manager in the business” – and I believed him!’

John was back fully immersed in the showbusiness world again and would continue to fill in acting roles here and there as the 1950s wore on. He was making a living being in and around the theatre, without appearing in the spotlight, but that was as close as he could get without anything stellar on his CV. Yet.

This continued into the new decade and, now aged 26, John must have had grave doubts that he would ever progress from stage management to regular acting roles. But finally, the opportunity he had waited for presented itself – and it came in his home town.

Arthur Lane recalled during John’s 1976 This Is Your Life TV broadcast:

John was still my stage manager and we’d taken a production to the Grand Theatre in Blackpool At 4.30 p.m. on the opening night, the leading man came up to me pointing to his throat, but I couldn’t hear a word he was saying.

I said, ‘Are you telling me you’ve lost your voice?’ and he handed me a doctor’s certificate saying he had acute laryngitis. I had to think on my feet, so I said, ‘John, take a script – go in the dressing room, you’re on tonight playing the lead.’

He said, ‘What about my uniform?’ I told him to put on the one we had, and he said, ‘But this was made for a man who is six-foot four!’

I said, ‘John, don’t make this difficult! The curtain’s up in an hour’s time.’ Before we began, I went out front and explained to the audience what had happened and they gave John a standing ovation when he came on – he had the script in his hand throughout and if he looked at it twice during the show, that was as much as he did.

John had proved beyond doubt that he could hold his own in a production and the fact he had done everything at the drop of a hat was testament to his professionalism, versatility and ability – not to mention confidence.

Arthur Lane was delighted, and John was handed various roles as he toured with Lane’s company for several months. Here he met his first boyfriend of note in Kenneth Hendel. John had never made being gay anybody else’s business and it was still a time when homosexuality was frowned upon, but his relationship with Hendel was not a secret in the theatre world. The pair were discreet but were clearly ‘an item’.

Actress Christine Ozanne was part of the Chester rep company and she recalls:

I first met John at the Royalty Theatre in 1962, which closed for good in 1966. John was the stage manager at the time and filling in acting gaps here and there when an opportunity arose.

Arthur Lane was the central character in most of the productions there and he was terrible! He was a rogue and vagabond! We did a tour in 1962 – maybe six or seven dates around the country in a terrible play called Done in Oils about an interior decorator and John was one of a couple of decorators.

He got all the laughs with his flat cap up a ladder and he was so funny. John made all his own costumes – absolutely everything. I remember seeing him once make a wig out of wood shavings as he planed a piece of wood and took these curly thin strips of wood and created a wig – he was a genius.

It was around this time that John also met and became close friends with Barry Howard, with the pair instantly clicking with their roguish sense of humour and love of dressing up as dames. It would be a friendship that lasted many years and would become particularly profitable when they began playing the Ugly Sisters in panto productions of Cinderella in years to come.

‘When John sang in panto with Barry, it was a bit like Flanagan and Allen – one kept the tune while the other more or less spoke the words,’ recalled Ozanne.

John had outgrown rep and was ready for bigger and better things. His star was slowly ascending and the opportunities for better work were more frequent – one offer in particular, working for two renowned theatre impresarios, would pay off handsomely. In a 1986 TV interview, he recalled:

I actually got a very good job in 1962 working for George and Alfred Black and got paid an enormous amount of money – £25 per week, which was a fortune at the time.

I was in a play called What a Racket for the summer season at the Arcadia in Scarborough and Albert Modley played my father – it was his show – and he was marvellous to me.

I learned a valuable lesson in that, too. Albert was cleaning my shoes because my character was going to be a teenage pop star and his dad – Albert – was out of work. That was the whole premise of the story, and we had this scene when he said, ‘You can’t go on like this – what are you going to be in a couple of years’ time?’ – and I said, ‘18 dad’ and he’d clip me around the ear with this brush.

But instinctively, I was standing about two feet upstage, which meant that Albert had to turn his neck around to look at me and say the line. Alfred Black was watching the rehearsals and he said, ‘John, come over here for a moment’, which I did. He then said: ‘We’re paying Mr Modley a lot of money – a lot more than we’re paying you – and we don’t want to see the back of his neck … we want to see his face, so if you can come down stage a little bit, that would be perfect.’

And that’s another lesson I never forgot. After that, George and Alfred used to look after me and I was given a part in a summer farce with Sid James in Wedding Fever and by also playing outrageous characters in various shows.

I worked very well with Sid, and I remember in one scene, I did my first ad lib and thought I was going to get in trouble for it. My character was sat at a table and the woman I was visiting offered me a cup of tea. She gave me a cup filled with dried tea and I just said, ‘Do you think I could get a drop of water with it?’

It got a huge laugh, but during the interval, I went up to Sid and said, ‘I’m ever so sorry, but I just felt it was a good line.’ Sid said not to apologise and anything I wanted to add in, I should. He said, ‘You’re a very good actor and I’m a very good reactor, so you say that line and I’ll react to it, and we’ll get another laugh.’

I did a summer season every year and a panto every year after that.

John would go to London and he moved in with Ken to be nearer the theatres and be available if and when more noticeable parts came up.

A mutual friend of Barry Howard’s and John’s – Paul Mead – recalls how he became part of a regular get-together when John and his partner Ken moved south to work. He said:

I was friends with Barry from Murdella Grammar School in Nottingham – he lived about half a mile away from me. I was a bit older than Barry and his dad owned the butchers near to my house.

I didn’t know him that well at school, but the first time we met was when I was in the company at Nottingham Playhouse, and he joined – it was his first job after leaving Birmingham Theatre School and he was in a play called The Shoemaker’s Holiday. In this business, you meet people and then you don’t see them for years – but when you do, you pick up where you left off.

I first met John in 1962 because a friend of mine called Anthony Linford was in the company with him at Chelmsford and when he wasn’t working, they used to have Friday night Monopoly sessions at John and Ken’s flat in Notting Hill Gate along with Gerald Moon and I was just sort of introduced and integrated into that. Ken was an actor as well – he was older than John and he eventually went to live in South Africa. That continued each week for a couple of years, and they went on from 8 p.m. to midnight. We’d have cheap booze because none of us had any money and remember John was struggling for work at the time.

That ended when John went on tour with Barry on a Salad Days tour which did extremely well – a play which I choreographed, played almost every role in and lived off for a year! John was very funny, especially when he was with Barry.

After the successes of What a Racket and another play he’d appeared in called Friends and Neighbours, Salad Days would prove John Inman’s biggest hit yet. The move south had been a wise one, and things were definitely moving in the right direction, if not quite at the speed he wanted. However, he was getting noticed – and earning more substantial roles as he went along.

The gamble to leave menswear behind had most definitely paid off.

3

Salad Days, Indeed

Arthur Lane’s production of Salad Days kept John Inman and Barry Howard in salad and much grander fayre for the best part of eighteen months as it toured up and down the land to packed houses. John played PC Boot in the musical, which also featured Patricia Duggan, Belinda Carroll and Noelle Finch – the latter would become one of John’s closest friends over the years to come.

The Inman–Howard partnership had also led to a lucrative panto opportunity, as they performed alongside one another as the Ugly Sisters in Cinderella – but also appeared together in Babes in the Wood, Mother Goose and Aladdin. They had quickly established themselves as the best panto double act in the business and were in high demand around the country for their festive hijinks.