Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

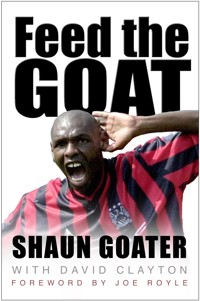

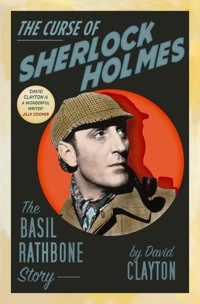

Basil Rathbone is synonymous with Sherlock Holmes. He played the Victorian sleuth in the fourteen Fox/Universal films of the 1930s and '40s, as well as on stage and radio. For many people, he is the Holmes. Basil Rathbone grew to hate Sherlock Holmes. The character placed restrictions on his career: before Holmes he was an esteemed theatre actor, appearing in Broadway plays such as The Captive and The Swan, the latter of which became his launchpad to greater stardom. But he never, ever escaped his most famous role. Basil Rathbone was not Sherlock Holmes. In The Curse of Sherlock Holmes, celebrated biographer David Clayton looks at the behind-the-camera life of a remarkable man who deserved so much more than to be relegated to just one role.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 261

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2020

This paperback edition published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© David Clayton, 2020, 2021

The right of David Clayton to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 5505 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

For Mum. My biggest fan.And for Marcia. Basil’s biggest fan.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Prologue

1 1892–1906: The Talented Mr ‘Ratters’

2 1909–1916: Theatrical Release

3 1917–1918: An Officer and a Gentleman

4 1918: Night Terrors

5 1920–1922: Onwards and Forwards

6 1922–1925: An Englishman in New York

7 1925–1926: Hollywood Beckons

8 1926–1929: Lights, Camera, Action!

9 1930–1933: England, my England?

10 1933–1935: Box Office and Hate Mail

11 1935–1937: Swashbuckling Away in Hollywood

12 1937–1938: Horror at Los Feliz Boulevard

13 1938–1939: Hollywood’s Evermore Reluctant Villain

14 1939–1941: The Game’s Afoot!

15 1940–1941: The Curious Case of Ouida Rathbone

16 1941–1944: Sherlock Takes Command

17 1944–1945: A Case of Lost Identity

18 1946: The Curse of Sherlock Holmes

19 1946–1951: Lost in New York

20 1951–1953: A Fall from Grace

21 1953–1960: The Admirable Mr Rathbone

22 1960–1967: Anything but Elementary

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House

The above is one of my favourite lines in all of literature. But what has it got to do with Basil Rathbone? Nothing. It does, however, have something to do with the writing of this book, which was also put together brick by brick (or word by word) with the floors (hopefully) firm and the doors (occasionally) shut.

Silence did indeed lay steadily at some points – several years, in fact – but at no stage did I walk alone.

In simple terms, this book would have been incredibly difficult to write but for the fantastic work of Marcia Jessen and Neve Rendell, both huge fans of Basil Rathbone and dedicated sleuths that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle himself would have been proud of. Marcia and Neve allowed me to mine their considerable collection of Rathbone material in the hope that I would be the biographer who would write about not only Basil’s life in the theatre and the movies, but his life and times away from the public eye – and certainly not focus solely on his time as Sherlock Holmes.

Marcia, I have to say, has gone above and beyond. No query was too great and her permission to share the mountains of research was generous and selfless. I owe Marcia so much and I’m very grateful to Neve as well – I just hope both ladies are happy with the final result!

My next big thank you is to my commissioning editor at The History Press, Mark Beynon. This has been a book seven years in the making and was due in 2013! For all that time, Mark gave me gentle nudges as to my progress. Towards the end, it was more a case of, ‘Oh well, I live in hope’ – just before the first chapters were sent in. Thanks, Mark – it would have been easy for you to wash your hands of this project, but your belief and persistence made me eventually fulfil my promise and also realise an ambition to write about Basil Rathbone.

Other people played a part in my research and I would like to express my gratitude to them: they include Kimi Ishikawa, whose father briefly worked for Basil; Alan Bennett for his help tracing ancestry of the Rathbone family; Major Ian Riley (retired) of the Liverpool Scottish Regiment; and Paul Stevens, librarian and archivist of Repton School. I’d also like to point out that the Repton School of Basil’s time bears no relation to the highly regarded and respected school of the present day in any way, shape or form.

There have been others who have helped me enormously, and that’s where Grace Clearsen comes in. Grace is the granddaughter of Basil Rathbone and she has provided a series of fascinating insights into Basil’s life and relationship with her late father, Rodion. While Marcia and Neve laid the foundations for my investigations, Grace confirmed that the life Basil Rathbone projected publicly was different from the one he actually lived. Dounia Rathbone, great-granddaughter of Basil, also helped me along the way and for that I am very grateful.

As ever, I’d also like to thank my wife Sarah, and my three incredible kids Harry, Jaime and Chrissie. As Stephen King once said in a dedication, ‘Promises to keep.’

Sadly, many of the actors that appeared with Basil in his many pictures and plays have passed away, but there was a treasure trove of memories in existence that I’ve knitted together, plus plenty of new revelations that I hope make this as fascinating to read as it was to write.

Make no mistake, Basil Rathbone is one of my favourite actors. For me, and millions of others around the world, it was his appearances as Sherlock Holmes that made me aware of his work. As a kid (and I know I’m not alone), I believed him to be a real person and was desperate to visit 221B Baker Street and see for myself the place the Great Detective had once called home.

When I began this biography, I had no idea just how many fantastic movies he had made or anything about his private life. He was a wonderful actor and the consummate professional with perhaps one of the greatest voices ever to grace showbusiness. But there will be times when you wonder how he did some of the things he did. Those moments are at odds with the warm and generous man whom so many people loved, and might have had a lot to do with the experiences and horrors he suffered during the war and his complicated and long marriage to Ouida Bergere. Those are judgements left to the reader to absorb and I doubt any two opinions will be the same. But I would add that there are so many instances and recollections of a warm and generous man in the pages that follow, which duel with some of the things Basil did in his life, that lead me to believe he must have deeply regretted certain moments in his life.

His portrayal of Sherlock Holmes will, in my view, never be bettered. He was the living embodiment of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s masterful creation and Basil’s Holmes movies have entertained millions for more than eighty years. Yet despite the exposure and wealth the role brought him, the relationship between actor and character would become torturous and the title of this book bears testament to that.

As Holmes himself once said, ‘How often have I said that when you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?’

Prepare to exclude the impossible. The game is, indeed, afoot.

David Clayton

Cheshire, England

September 2019

Prologue

Who should play Holmes?! Basil Rathbone, of course!

Twentieth Century Fox producer/directorGene Markey’s response to who should playthe lead in The Hound of the Baskervilles

The life and times of Basil Rathbone could have comfortably filled the pages of any Sir Arthur Conan Doyle classic work of fiction. Intrigue, drama, tragedy, mystery, romance and a sprinkling of the macabre: Rathbone was many things to many people, but unravelling the enigma of one of the greatest British actors of his generation – perhaps of all time – would take the great detective Sherlock Holmes himself to solve.

War hero, son, brother, actor, husband, father, lover … Basil Rathbone was all of these and more, yet the role he would eventually become synonymous with would also become his nemesis. Rathbone needed no Moriarty to continually torment him. In accepting the role of Sherlock Holmes, he had, in effect, cursed himself with a character he could never escape from professionally, and even when he attempted to effectively kill Holmes off, he suffered the same ignominy Conan Doyle had when he took the shock decision to finally see Holmes off once and for all in the infamous Reichenbach Falls incident. Millions of devoted fans of Holmes simply wouldn’t accept his death and the writer was forced to backtrack, resurrect him and continue writing about his adventures with his faithful accomplice Dr Watson for thirty-four more years.

In time, Holmes would exact his own revenge on Rathbone who came to loathe a character he saw as one-dimensional, condescending, cold and mean spirited. Even worse, he despised the tacky, almost mocking recognition he received in everyday life that became almost unbearable for him. His efforts to extricate himself from the great detective were ultimately doomed to failure and there would only be one winner.

Rathbone the actor deserved better, and Rathbone the man deserved better. Many of his close friends believed the same – but there had been casualties along the way, and unlike the movies he starred in, not everything was black and white. In fact, so intertwined did character and actor become in public consciousness, that for many, Rathbone really was Sherlock Holmes, and few could tell where Holmes ended, and Rathbone began.

One thing is for certain. For Sherlock Holmes purists – and they are legion – there was only one actor who was the living, breathing embodiment of the character Sir Arthur Conan Doyle first unleashed on the world in the 1887 short story A Study in Scarlet – and that man was, indeed, Basil Rathbone.

1

1892–1906

The Talented Mr ‘Ratters’

I am seeking, I am striving, I am in it with all my heart.

Vincent van Gogh

Philip St John Basil Rathbone was born on 13 June 1892, but the quintessential Englishman’s birth was not in the green valleys of England, but Johannesburg where his mother and father had been working and living for several years.

His parents had married in 1891. Edgar Philip Rathbone hailed from the affluent Rathbone family of Liverpool who were non-conformist merchants, shipowners and also the owners of the Liverpool, London and Globe Insurance Company. In fact, Basil – as baby Philip St John would be known – was the great-grandson of the noted Victorian philanthropist, William Rathbone V. It was a family tradition not to use the first name, so the Rathbones’ youngest child quickly became known as Basil.

Edgar was 36 years old when Basil was born, and his mother Anna, a talented violinist of Irish descent, was 25 when she gave birth to what was her first child. Edgar was a mine inspector and moved to Johannesburg along with many other professionals following the discovery of the Main Reef gold outcrop, which would see a sparsely populated area of South Africa become a vibrant hub, many attracted by the dreams of untold riches.

In all-too-familiar fashion, the news of a possible gold rush saw Johannesburg’s population quickly swell to more than 100,000 people, and as with any imagined get-rich-quick opportunities, so too came a raft of philanderers, criminals, pimps, adventurers and crooks. The Rathbones were settled on the Trene Estate in Pretoria and Basil was baptised on 26 March 1894 at St Mary the Virgin Church in the Parish of Johannesburg, Diocese of Pretoria, with his sponsors listed as Thomas F. Carden, Frederick H. George and Helen Beatrice George – the latter related to his mother Anna, whose maiden name was also George.

In 1895, everything changed for the Rathbone family. After the Boers accused Edgar of being a British spy, the Rathbones were forced into a daring escape that would have read well in any spy novel. Years later, Basil would recount their dramatic escape as he wrote:

Once again, under cover of darkness, we left our sanctuary. Upon arrival at the railroad station we found that train service had been considerably disrupted. There was however a freight train leaving in a couple of hours.

The situation was too urgent to wait for a passenger train in the morning. So, we boarded a freight car and prepared for the long haul to Durban. It is some three hundred odd miles from Johannesburg to Durban, one hundred and twenty miles of which would be consumed in reaching the Natal Border – one hundred and twenty miles – and every mile fraught with danger to us all. We were fortunate in finding a car not too heavily loaded, in which there appeared to be adequate room for brief exercising should circumstances allow such a luxury. At one end of the car there was a small wooden seat. There my mother sat with her two children in her arms, while underneath it crouched my father, well hidden by the voluminous folds of my mother’s skirt. Intermittently could be heard the sounds of voices and the coupling and uncoupling of cars as the freight train was made up. Every start held the promise that we were on our way, and the hope that my father could take a brief respite from his cramped hiding place.

The drama was far from over for the Rathbone family, who may have arrived safely in Durban, but were in no fit state to travel further as Anna was sick and soon diagnosed as having typhoid fever. She was admitted to hospital, and a day later Basil and his sister fell foul of the same illness and all three were seriously ill for several weeks and under intensive medical care. It could have been the end of young Basil’s adventure before it had really begun, but thankfully mother and children recovered fully and were finally ready to return to England.

They had wisely fled Johannesburg in a hurry and finally managed to make good their escape from South Africa, though there was one final twist. They had been booked to sail back to England on the Union Castle, but during Anna’s delirious state in hospital she had suffered a nightmare so terrifyingly real that when she had recovered, she had begged Edgar not to sail on the ship in question. She had, in her mind, seen a portent of disaster so vivid, she was convinced it was a premonition of her family’s death.

The dream saw a normal passage for the Union Star until it reached the Bay of Biscay, where it encountered a terrific storm. Not only did she see her family stranded as the ship began to list, but she heard the Seaforth Highlanders band playing ‘Flowers of the Forest’ as the ship started sinking – that’s when she awoke, certain that her family were in mortal danger.

Sceptical, but understanding, Edgard switched the sailing to the Walmer Castle liner a week later. In Basil’s autobiography, published in 1962, he writes that the Union Castle did indeed sink during a terrible storm in the Bay of Biscay, with all souls drowned as the Seaforth Highlanders band played ‘Flowers in the Forest’. He said his mother could never have lied and his father backed up the story, but there is no obvious record of the Union Castle ship existing or a liner being lost at that time. Though Basil writes that the Union Castle Line shipping company could confirm these facts, they didn’t come into existence until 1900, a few years after their voyage home. Perhaps the legend of the nightmare had grown and been embellished over the years in the family, to a point where it could no longer be undone. Or perhaps it was a different shipping company? Basil was only 4 at the time and when he wrote his memoirs, his parents had long since passed away. It’s likely we’ll never fully know the truth.

Regardless of the journey, the Rathbones were finally home and ready to settle into a new life in London. In later years, Basil recalled vague memories of the period and admitted he didn’t know (or care) if his father really had been a spy or not because he had never asked him, though it is fair to say there was a mistrust and a certain amount of resentment from the Boers during the period the Rathbones and any other British citizens were in the country, mostly due to the First Boer War. Perhaps, in their eyes, all were the enemy, and all were spies. Whatever Edgar’s real mission had been, it was all in the past now and it was time to move on.

Initially, the family lived at 145 Goldhurst Terrace in Hampstead, London. The residence was owned by a woman named Susannah Kinchingman, who was approximately 47 years old when the Rathbones took residence there, and for the 1901 Census Basil was listed as her son, though it is unclear why. Susannah was recorded as the ‘Head of the house’. Today, the house, which still stands, is worth more than £1 million. It is most likely that, back then, it was a boarding house of some sort.

By 1901, Edgar was listed as a mining engineer and Basil spent his early years as a Londoner, taking great inspiration from his older cousin Frank Benson, a highly respected actor who had founded his own company and specialised in Shakespearian productions, many of which were based on long-forgotten or largely ignored tales from the great Bard. Benson was something of a hero to the juvenile Basil, who was fascinated by the theatre. It is fair to say that Benson was one of England’s greatest classical actors of the time, and for thirty years he managed the Shakespearian Festival in Stratford-on-Avon, and though there is no proof as such, it is hard to think that an awestruck Basil didn’t see some of his cousin’s productions in London at some stage. Basil bore an uncanny resemblance to Frank Benson, too. Acting, it seemed, was very much in his DNA.

He enjoyed what he described as a ‘very sweet’ childhood. Younger brother John had been born and the family was complete, and they soon moved to their own property as Edgar found his feet again in London society. Basil’s romantic leanings were evident even at a young age, when he began dating a girl called Esther who lived close by, and with her he shared his first kiss in the hayloft at the farm near to his home.

He spent idyllic Christmas holidays with his grandparents, and occasionally the family would visit their wealthy relatives at Greenbank Cottage in Wavertree, Liverpool, where he would again fall head over heels in love with their neighbour’s daughter, Cynthia. Basil was a hopeless romantic, but he saw Cynthia dressed as a Fairy Queen and was completely smitten.

He knew her for just one day, dreaming of when he would see her again – but the next morning she had gone on holiday to Europe, and with his grandmother’s passing not long after, he would never return to Greenbank Cottage again. But he never forgot Cynthia.

He wrote and directed a family production while at his grandmother’s residence – a pantomime – but as he’d written the best part and dialogue for himself, his siblings didn’t put their heart and soul into the production! Still, it was his first attempt at what would eventually become his passion.

But a career in acting would have to wait and, aged 13, Basil had set his heart on public school, and one in particular: Repton, a long-established school some 140 miles north in Derbyshire. Basil knew of Repton’s reputation as perhaps the foremost sporting school in the country at that time, and this was the driving force behind his determination to get there. He was a natural sportsman and a fierce competitor, so he was somewhat economical with the truth when insisting to his parents that Repton was the school where he would excel academically. Repton came at a price and it would be a sizeable financial commitment for his parents, but their support was never in question. Basil won a place at Repton, where he would board and stay during school term; however, he would keep the real reasons he was going there to himself. From September 1906 to April 1910, Basil was in a boarding house called Cattley’s.

Already standing 6ft tall, Basil was a natural leader, and though he would struggle academically, Repton would allow him to thrive on the sports field. His sporting prowess quickly made him a popular figure amongst his peers, and this undoubtedly made his time at the school far more palatable than the fate of some of its less confident pupils.

Despite its reputation for education, sport and discipline, at the time it was a case of survival of the fittest at Repton, where bullying and ‘fagging’ – younger boys acting as servants to older boys – was a rife and even accepted tradition, with many of the masters turning a blind eye. Beatings, antisemitism and homosexual relationships were recorded in Repton’s discipline log – also known as the ‘Black Book’ – and those who did suffer at the hands of others often underwent anguish and mental torment. Some years later, bestselling author Roald Dahl wrote of his experiences at Repton in his autobiographical tale Boy, claiming: ‘All through my school life I was appalled by the fact that masters and senior boys were allowed literally to wound other boys, and sometimes quite severely… I couldn’t get over it. I never have got over it.’

For Basil, however, life at Repton would be different. His four years there were afforded a chapter in his autobiography, In and Out of Character. Nicknamed ‘Ratters’, he seemed to relish his time as a Reptonian, and though he was devastated not to be selected to represent the school at cricket, his ability at football would elevate his status yet further. He recalled:

Football boots, well soaked in ‘dubbin’ against the invariably inclement weather – football boots with their masculine leather thongs… upon the notice board outside Pears’ Hall – that magic word – ‘Hopefuls’… one day my name was on that board… the first step towards one’s colours.

Days when one had played badly – inspired days when one played with the thought of someday playing for England! Then, at last, that cold, wet afternoon when I.P.F Campbell, our captain, walked slowly towards me and took my hand on the football field. I had won my colours! A roar of young voices approving his choice, and a moment later, one was lifted on to the shoulders of one’s friends and carted in triumph from the field of play. Later, one was to hear such applause again – many times – but no first night in any theatre anywhere held such ecstasy of accomplishment as that moment when one received one’s colours at Repton School.

Naturally athletic, Basil’s height, physique and speed ensured he would become a major asset for Repton’s sporting reputation, though it was to the detriment of his education, where Basil admitted to putting his learning a firm second to the football field and athletic track. He wrote: ‘I scraped through my exams, remaining pretty much at the bottom of my classes except for Carr and Vatchell, my bosom friends who I could rely upon to keep me out of bottom place.’

One sports day recorded in the school magazine has Basil finishing fourth in the steeplechase, while winning the 600m sprint and the Under-17s hurdles race. He also made it into the dreaded Black Book with the following entry: ‘July 5th, 1909: Rathbone, Basil: Rowdy behaviour on Cricket Field on Sunday. Also disparaging Head Boy’s warning and then lying about it. Flogged.’

Yet, when he did put his mind to it, Rathbone clearly had at least some academic ability, surprising both his teachers and friends by winning an essay competition – so much so, that his friends thought it must be a fluke! It also backfired somewhat in that it also convinced some of his masters that he was a ‘slacker’ who simply couldn’t be bothered putting his heart and soul into education. The truth probably lay somewhere in between. He had already shown where his true passions lay and though he had the tools and imagination to succeed, he was all too aware that his other secret love – that of the theatre – would have changed his standing at the school entirely. As a sportsman, he was safe from the bullying and ridicule gentler, more artistic souls had been subjected to at Repton, and Basil had enough nous to keep his own thespian interests firmly to himself. He said:

Little did my friends realise that, during homework in the dining room, I was working on my first play, ‘King Arthur’. Had my friends known, this would have indicated to them that I was not quite the ‘he-man’ they thought me to be. Repton was not a school that prided itself on the arts and any boy so interested would definitely be suspect of being a ‘queer one’. And so, I kept my love of the theatre to myself.

It was a wise decision. Basil felt incredibly guilty about the financial hardship his parents suffered as a result of his schooling, hardships also felt by his younger siblings, sister Beatrice and brother John, though he said nobody in his family had held it against him and gave what they had ‘affectionately and willingly’. The guilt stemmed from his academic results – or lack of – and the real reasons he’d wanted to attend Repton in the first place. Yet in many ways the decision was correct, as he was able to gain confidence, social standing, fulfil his competitive needs and achieve sporting prowess: assets that he would take and utilise into his future career – though, after leaving Repton behind, he would first have to negate his father’s slightly more grounded vision of where his future employment lay…

2

1909–1916

Theatrical Release

Destiny is no matter of chance. It is a matter of choice. It is not a thing to be waited for, it is a thing to be achieved.

William Jennings Bryan

Aged 17, and with his whole life in front of him, Philip St John Basil Rathbone was ready to take on the world. His triumphant stay at Repton had seen him carried through school largely on his athletic prowess, with his academic achievements a very poor second.

Having successfully kept his love of acting and playwriting a secret, he was now free of the masculine shackles he felt school had kept him in during his time there, and was ready to follow his true calling. His dream of becoming an actor was not dismissed by his parents, but the sacrifices they’d made for their son to attend such a prestigious place of learning needed some form of recompense and their teenage son duly accepted as much. For now.

Frank Benson was the son of Basil’s mother Anna’s sister, and the likeness to Basil was incredible. Edgar must have been aware of how much Basil looked up to his older cousin – he was thirty-four years his senior – and Benson’s passion for Shakespeare. It was as though Basil was Frank Benson junior, and Edgar and Anna probably realised their son would eventually follow his true calling to the stage, sooner rather than later.

Edgar had organised a position for Basil as a junior clerk at the Globe Insurance Company in London, where he was expected to learn the business and perhaps forge a steady career for himself. Dutifully, he accepted the role, no doubt feeling indebted to his parents and particularly his father, who had no doubt hoped his son’s acting aspirations would eventually fade.

But there was little chance they would, and it was to be a fairly brief brush with the insurance world, with the budding actor desperate to forge a career of his own volition. Recalled Basil:

My father asked me to compromise by going into business for one year, at the end of which time I might do as I pleased. It was a generous compromise. And so, I became a junior clerk in the main office in London branch of the Globe Insurance Company and with him it was made clear that I was due for early promotion, provided I worked hard. I was given special instruction and attended lectures after hours, and within a few months I was moved to the accounting department of the West End Branch at Charing Cross, under the local management of E. Preston Hytch – a bald-headed, hard-working Dickensian, with very little discipline over his staff. During this period, I was elected to play cricket and football, every Saturday afternoon for the L, L & G’s first team. I was also invited to spend a weekend with Mr and Mrs Lewis and their eligible daughter. It was all so obvious and made no impression on me, except to increase my determination to be rid of them all at the end of the one year.

On 22 April 1911, he finally got the opportunity he’d been waiting for. Using his family connections, he won the part of Hortensio in Sir Frank Benson’s No. 2 Company production of The Taming of the Shrew at the Theatre Royal in Ipswich. The No. 2 company was made up of promising young talent, still finding their feet, but it was a highly respected branch of the Benson empire – a sort of academy of aspiring actors.

Directed by Henry Hubert, the teenage Rathbone impressed sufficiently to be invited on a tour of the United States with Benson’s troop in October 1912. The chance to take Shakespeare to the States, and playing roles such as Paris in Romeo and Juliet, Fenton in The Merry Wives of Windsor and Silvius in As You Like It, was impossible to turn down. He was doing what he loved, earning a living and travelling the world as he honed his craft. The trip to the United States would also be the beginning of a lifelong love with a country he would eventually call home in years to come. Basil was in his element and thrived on tour, winning wide acclaim for a striking performance in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Like cousin Frank, he was a devoted student of Shakespeare and this was his destiny. Everything, it seemed, was going to plan.

With Benson’s Shakespeare Festival in Stratford-upon-Avon still going strong, Basil would appear in many varied productions as he shaped into the classical actor that would bring wealth and fame in later life. It was also there that he would meet actress Marion Foreman, with whom he would fall hopelessly in love. In his autobiography, Rathbone wrote: