30,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

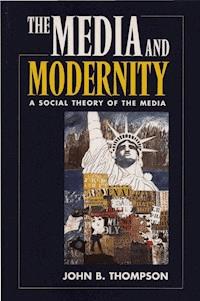

In this major new work, Thompson develops an original account of ideology and relates it to the analysis of culture and mass communication in modern Societies.

Thompson offers a concise and critical appraisal of major contributions to the theory of ideology, from Marx and Mannheim, to Horkheimer, Adorno and Habermas. He argues that these thinkers - and social and political theorists more generally - have failed to deal adequately with the nature of mass communication and its role in the modern world. In order to overcome this deficiency, Thompson undertakes a wide-ranging analysis of the development of mass communication, outlining a distinctive social theory of the mass media and their impact.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 783

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Copyright ©John B. Thompson 1990

The right of John B. Thompson to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published 1990 by Polity Pressin association with Blackwell Publishers LtdReprinted 1992, 1994, 1996, 2006, 2007

Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge, CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN: 978-0-7456-6876-5 (Multi-user ebook)

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 11½ on 12½ pt Bembo by Joshua Associates Ltd, Oxford Printed and bound in Great Britain by Marston Book Services Limited, Oxford

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.polity.co.uk

Preface

Introduction

1 The Concept of Ideology

Ideology and the Ideologues

Marx’s Conceptions of Ideology

From Ideology to the Sociology of Knowledge

Rethinking Ideology: A Critical Conception

Reply to Some Possible Objections

2 Ideology in Modern Societies

A Critical Analysis of Some Theoretical Accounts

Ideology and the Modern Era

Ideology and Social Reproduction

The Critique of the Culture Industry

The Transformation of the Public Sphere

3 The Concept of Culture

Culture and Civilization

Anthropological Conceptions of Culture

Rethinking Culture: A Structural Conception

The Social Contextualization of Symbolic Forms

The Valorization of Symbolic Forms

4 Cultural Transmission and Mass Communication

The Development of the Media Industries

Aspects of Cultural Transmission

Writing, Printing and the Rise of the Trade in News

The Development of Broadcasting

Recent Trends in the Media Industries

The Social Impact of New Communication Technologies

5 Towards a Social Theory of Mass Communication

Some Characteristics of Mass Communication

Mass Communication and Social Interaction

Reconstituting the Boundaries between Public and Private Life

Mass Communication between Market and State

Rethinking Ideology in the Era of Mass Communication

6 The Methodology of Interpretation

Some Hermeneutical Conditions of Social-Historical Inquiry

The Methodological Framework of Depth Hermeneutics

The Interpretation of Ideology

Analysing Mass Communication: The Tripartite Approach

The Everyday Appropriation of Mass-Mediated Products

Interpretation, Self-Reflection and Critique

Conclusion: Critical Theory and Modern Societies

Notes

Index

This book is a development of the ideas which were initially sketched in an earlier volume, Studies in the Theory of Ideology. The earlier volume was concerned primarily with the critical assessment of a number of outstanding contributions to contemporary social theory. In the course of that assessment I put forward some constructive ideas about the nature and role of ideology, its relation to language, power and social context, and the ways in which ideology can be analysed and interpreted in specific cases. My aim in this book is to take up these ideas, to develop them and incorporate them into a systematic theoretical account. This is an account which is certainly informed by the work of others - other theorists as well as others engaged in empirical and historical research. But I have tried to go beyond the material upon which I draw and to which I am indebted, in an attempt to stretch the existing frameworks of analysis and to provide some stimulus to further reflection and research.

While in many ways this book is a continuation of the project announced in Studies, there is one respect in which it differs significantly from the earlier volume: in this book I have sought to give much more attention to the social forms and processes within which, and by means of which, symbolic forms circulate in the social world. I have therefore devoted considerable space to the nature and development of mass communication, which I regard as a definitive feature of modern culture and a central dimension of modern societies. My analysis of the nature of mass communication and of the development of media institutions raises more issues than I can adequately address within the scope of this book, but they are issues which I plan to pursue further in a subsequent volume on social theory and mass communication.

In thinking about the ideas discussed in this book, I have benefited from the comments and criticisms of others. Anthony Giddens and David Held deserve particular mention: they have been partners in an ongoing dialogue which has been, and no doubt will continue to be, invaluable. Peter Burke, Lizbeth Goodman, Henrietta Moore and William Outhwaite read an earlier version of this text and gave me a great deal of helpful and encouraging feedback. I am also grateful to Avril Symonds for her skilful word-processing, to Gillian Bromley for her meticulous copy-editing, and to the many people at Blackwell-Polity and Stanford University Press who have contributed to the production and diffusion of this text. Finally, I should like to thank the friends who, in the course of the last couple of years, have helped to create the space for this book to be written: their generosity has meant much more to me than a few words of acknowledgement might suggest.

J.B.T., Cambridge, December 1989

Today we live in a world in which the extended circulation of symbolic forms plays a fundamental and ever-increasing role. In all societies the production and exchange of symbolic forms - of linguistic expressions, gestures, actions, works of art and so on - is, and has always been, a pervasive feature of social life. But with the advent of modern societies, propelled by the development of capitalism in early modern Europe, the nature and extent of the circulation of symbolic forms took on a new and qualitatively different appearance. Technical means were developed which, in conjunction with institutions orientated towards capital accumulation, enabled symbolic forms to be produced, reproduced and circulated on a hitherto unprecedented scale. Newspapers, pamphlets and books were produced in increasing quantities throughout the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; and, from the nineteenth century on, the expanding means of production and circulation were accompanied by significant increases in levels of literacy in Europe and elsewhere, so that printed materials could be read by a growing proportion of the population. These developments in what is commonly called mass communication received a further impetus from advances in the electrical codification and transmission of symbolic forms, advances which have given us the varieties of electronic telecommunication characteristic of the late twentieth century. In many Western industrial societies today, adults spend on average between 25 and 30 hours per week watching television - and this is in addition to whatever time they spend listening to the radio or stereo, reading newspapers, books and magazines, and consuming other products of what have become large-scale, trans-national media industries. Moreover, there are few societies in the world today which are not touched by the institutions and mechanisms of mass communication, and hence which are not open to the circulation of mass-mediated symbolic forms.

Despite the growing significance of mass communication in the modern world, its nature and implications have received relatively little attention in the literature of social and political theory. To some extent this neglect is due to a disciplinary division of labour: social and political theorists have been content, mistakenly in my view, to leave the study of mass communication to specialists in media and communications research. To some extent this neglect is also a consequence of the fact that the problems which preoccupy many theorists today are a legacy of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century thought. It is the writings of Marx and Weber, of Durkheim, Simmel, Mannheim and others which have, in many respects, set the agenda for contemporary theoretical debates. Of course, the legacy of these and other thinkers is not necessarily a millstone. As commentators on the social transformations and political upheavals which accompanied the development of industrial capitalism, these thinkers called attention to a range of social phenomena, and elaborated a series of concepts and theories, which remain relevant in many ways to the circumstances of the late twentieth century. But where there is insight and illumination, there is also blindness, over-simplification, wishful optimism. Part of the task that confronts social and political theorists today is to sift through this legacy and to seek to determine what aspects can be and should be retained, and how these aspects can be reconstructed to take account of the changing character of modern societies. In confronting social and political phenomena we do not begin with a tabula rasa: we approach these phenomena in the light of the concepts and theories which have been handed down from the past, and we seek in turn to revise or replace, criticize or reconstruct, these concepts and theories in the light of the developments which are taking place in our midst.

In the following chapters I shall take as my starting point the concept and theory of ideology. A notion which first appeared in late eighteenth-century France, the concept of ideology has undergone many transformations in the two centuries since then. It has been twisted, reformulated and recast, it has been taken up by social and political analysts and incorporated into the emerging discourses of the social sciences; and it has filtered back into the everyday language of social and political life. If I take the concept and theory of ideology as my starting point, it is because I believe that there is something worthwhile, and worth sustaining, in the tradition of reflection which has been concerned with ideology. Although there is much that is misleading and much that is erroneous in this tradition, we can nevertheless distil from it a residue of problems which retain their relevance and urgency today. The concept and theory of ideology define a terrain of analysis which remains central to the contemporary social sciences and which forms the site of continuous and lively theoretical debate.

I shall be concerned to argue, however, that the tradition of reflection on ideology also suffers from certain limitations. Most importantly, the writers who have concerned themselves with problems of ideology have failed to deal adequately with the nature and impact of mass communication in the modern world. Some of these writers have certainly acknowledged the importance of mass communication - indeed, they were among the first social and political theorists to call attention to the growing role of the mass media. But even these writers tended to take a rather dim view of the nature and impact of mass communication. They were inclined to regard the development of mass communication as the emergence of a new mechanism of social control in modern societies, a mechanism through which the ideas of dominant groups could be propagated and diffused, and through which the consciousness of subordinate groups could be manipulated and controlled. Ideology was understood as a kind of ‘social cement’, and mass communication was viewed as a particularly efficacious mechanism for spreading the glue. This general approach to the relation between ideology and mass communication is one which I shall criticize in detail. It is an approach which has, explicitly or implicitly, moulded many of the recent contributions to the ongoing debate about ideology and its role in modern societies, as well as some of the attempts to reflect theoretically on the nature and impact of mass communication. And yet it is, in my view, an approach which is fundamentally flawed.

One of my central aims in this book is to elaborate a different account of the relation between ideology and mass communication - or, to put it more precisely, to rethink the theory of ideology in the light of the development of mass communication. In pursuing this aim I shall adopt a three-stage argumentative strategy. I shall begin by reconsidering the history of the concept of ideology, retracing its main contours and its occasional detours. Against the backcloth of this brief analytical history, I shall formulate a particular conception of ideology which preserves something of the legacy of this concept while dispensing with assumptions which seem to me untenable. I shall then examine some of the general theoretical accounts which have been put forward in recent years concerning the nature and role of ideology in modern societies. I shall argue that these accounts are inadequate in numerous respects, particularly with regard to their treatment of mass communication and its significance for the theory of ideology.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!