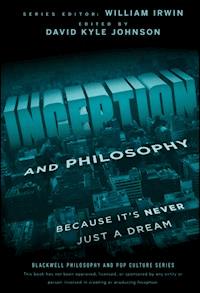

Inception and Philosophy E-Book

13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

- Sprache: Englisch

A philosophical look at the movie Inception and its brilliant metaphysical puzzles Is the top still spinning? Was it all a dream? In the world of Christopher Nolan's four-time Academy Award-winning movie, people can share one another's dreams and alter their beliefs and thoughts. Inception is a metaphysical heist film that raises more questions than it answers: Can we know what is real? Can you be held morally responsible for what you do in dreams? What is the nature of dreams, and what do they tell us about the boundaries of "self" and "other"? From Plato to Aristotle and from Descartes to Hume, Inception and Philosophy draws from important philosophical minds to shed new light on the movie's captivating themes, including the one that everyone talks about: did the top fall down (and does it even matter)? * Explores the movie's key questions and themes, including how we can tell if we're dreaming or awake, how to make sense of a paradox, and whether or not inception is possible * Gives new insights into the nature of free will, time, dreams, and the unconscious mind * Discusses different interpretations of the film, and whether or not philosophy can help shed light on which is the "right one" * Deepens your understanding of the movie's multi-layered plot and dream-infiltrating characters, including Dom Cobb, Arthur, Mal, Ariadne, Eames, Saito, and Yusuf An essential companion for every dedicated Inception fan, this book will enrich your experience of the Inception universe and its complex dreamscape.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 590

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

The Editor’s Totem: An Elegant Solution for Keeping Track of Reality

Introduction: Plato’s Academy Award

Part One: Was Mal Right? Was It All Just A Dream?: Making Sense of Inception

Chapter 1: Was It All a Dream?: Why Nolan’s Answer Doesn’t Matter

The Major Interpretations

Clues from the Work

What Nolan Says

Why We Shouldn’t Care What Nolan Says

The Epistemic Problem

The Interpretively Static Problem

The Collective Ownership Problem

So What’s the Alternative?

Chapter 2: Let Me Put My Thoughts in You: It Was All Just a Dream

A Stalemate between Views

How to Go Beyond the Evidence

A Helpful Principle

Avoiding Criticism

“You Never Really Remember the Beginning of a Dream”

Is Dreaming Worse?

Chapter 3: Even If It Is a Dream, We Should Still Care

Dreams Don’t Matter?

Spinning, Falling, or Perpetually Wobbling, It’s Still Just a Movie

The Paradox of Fiction

Don’t Worry, You’re Not Really Scared

The Art of Feeling about Art

Maybe We Just Can’t Help Ourselves

Can You Relate?

A Failed Inception

Chapter 4: The Unavoidable Dream Problem

The Dream Problem

Ways Out of Skepticism: (1) Descartes’ Solution

Ways Out of Skepticism: (2) Modern Science and Reality

Ways Out of Skepticism: (3) Pragmatism, the Last Resort?

Part Two: Is The Top Still Spinning?: Tackling The Unanswerable Question

Chapter 5: The Parable of the Spinning Top: Skepticism, Angst, and Cobb’s Choice

Angst and Meaningfulness

The Philosopher’s Response: Denouncing Skepticism

The Basement Dreamers’ Response: Escape Reality

Mal’s Response: Forget the Dream

Cobb’s Response: Choosing Reality

Taking the Leap

Chapter 6: Reality Doesn’t Really Matter

Limbo Is Great, the Real World Ain’t

Why All the Hoopla about Reality?

Turning the Tables

Familiarity Breeds Approval

Landslide on Mount Nozick

The Problem with Reality-Spotting

Why Reality Doesn’t Matter

Chapter 7: Why Care whether the Top Keeps Spinning?

Epistemology, Descartes, and Skepticism

Ethics, Nozick, and Hedonism

Totems as Elegant Solutions to Skepticism?

Why Care whether the Top Keeps Spinning?

What Matters in Life

Philosophy and Everyday Life

Part Three: Is Inception Possible?: The Metaphysics, Ethics, and Mechanics of Incepting

Chapter 8: How to Hijack a Mind: Inception and the Ethics of Heist Films

Moviemaking as Inception

Planning the Heist

Homer Hijacks the Republic

Dreams within Dreams

Resolving Issues in Dreams

Dream Bigger

Chapter 9: Inception, Teaching, and Hypnosis: The Ethics of Idea-Giving

Indoctrination and Teaching

What If Cobb Hypnotized Fischer?

Mal, Fischer, and the Ethics of Inception

“You Need to Let Them Decide for Themselves”

Chapter 10: Inception and Free Will: Are They Compatible?

Alternate Wills

We May Not Be Free

Compatibilism

Frankfurt Counter Examples

Should We Worry?

Chapter 11: Honor and Redemption in Corporate Espionage

Choosing a Life of Crime

The Hero Is Not a Thief?

The Result Should Not Justify the Method

Moral Hazard

Family Matters

The Oxymoron of Ethical Corporate Espionage

Downward Is the Only Way Forward

Part Four: What is Dreaming?: Exploring The Nature of (Shared) Dreams (Upon Dreams)

Chapter 12: Shared Dreaming and Extended Minds

Extended Minds

Collective Minds

Blended Minds

The Movie as Shared Thought

Chapter 13: Morally Responsible Dreaming: Your Mind Is the Scene of the Crime

Moral Responsibility

Is Cobb’s “Dream Self” Cobb?

The Dream Is Real

But They Know It’s a Dream

Alternative Dream Possibilities

Dream Actions That Have Effects in the Real World

“I Need to Get Home. That’s All I Care about Right Now”

Facing the Moral Dream Problem

Chapter 14: Dream Time: Inception and the Philosophy of Time

Trying to Make Sense of Time

The Measure of Movement

Believing in Time

The Sense of Time

The Speed of Thought

The Speed of a Dream

Dream Simultaneity

Chapter 15: Dreams and Possible Worlds: Inception and the Metaphysics of Modality

A Possible World Primer

Men Possessed by Radical Notions: Spinoza, Leibniz, and Lewis

Architects, God, and Evil Worlds

The Laws of Nature and the Possibility of Miracles

Dreams and the Possibility of Paradox

It’s Never Just a Dream: Reality in Inception

Chapter 16: Do Our Dreams Occur While We Sleep?

Norman Malcolm’s Dreaming

Temporal Location and Duration of Dreams

Mental Activity during Sleep

Is Malcolm’s Extraction Successful?

Is Inception Nonsense?

Part Five: Should I Take A Leap of Faith?: Religious Themes in Inception

Chapter 17: Taking a Leap of Faith: A How-to Guide

What Is Faith?

The Pitfalls of Blind Faith

Existential Matters

An Example of Rational Faith

Faith That We Are Not Dreaming

A Rule to Follow

Unavoidable Irrationality?

The Ethics of Belief

Chapter 18: Limbo, Utopia, and the Paradox of Idyllic Hope

On the Shores of Utopia

Nolan’s Dystopian Future and the Emergence of a New Global Superpower

“Downwards Is the Only Way Forwards”

Who Wants to Be Stuck in a Dream?

Does It Depend on the Dream?

Why Is Dreaming So Important?

Chapter 19: Unlocking the Vault of the Mind: Inception and Asian Philosophy

Wake Up and Smell the Wasabi: Dreams in Asian Philosophy

Mind as Fortress and Vault: The Paradox of Accessing the Inaccessible

Mind as Mirror: Just What Exactly Is Being Reflected, and Who Reflects?

Mind as Womb: The Ethics of Insemination

Cobb’s Wet Dream: The Ocean as a Consummate Metaphysical Metaphor

Mind as Emptiness: What Happens When the Spinning Top Stops Spinning?

Is Saito an Old Man Dreaming That He Is Flying?

Lucid Ambiguity: Paradoxically Obscuring and Clarifying Dreams

Part Six: What Does It All Mean?: Finding The Hidden Lessons of Inception

Chapter 20: Mal-Placed Regret

Hell Hath No Fury Like a Woman Scorned

“One Simple Idea Could Change Everything”

Regret and Guilt

Descartes on Regret

Well-Placed Regret

Postscript

Chapter 21: “You’re Just a Shade”: Knowing Others, and Yourself

Mission Planning

“You’re Keeping Her Alive”: The Problem of Projections

Is Consciousness “Windowless”?

Is Shared Privacy an Oxymoron?

Can We Still Feel the World through the Walls?

Can We Even Know Ourselves?

Encountering the Other

Chapter 22: Paradox, Dreams, and Strange Loops in Inception

What Is a Paradox?

Why Thinking about Paradox Is Useful

The Paradox of Dreaming

Strange Loops

The Paradox of Human Subjectivity

Paradox, Creation, and Memory

Paradoxes and a Leap of Faith

Appendix: A Safe Full of Secrets: Hidden Gems You May Have Missed

Contributors

Index

The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

Series Editor: William Irwin

South Park and Philosophy

Edited by Robert Arp

Metallica and Philosophy

Edited by William Irwin

Family Guy and Philosophy

Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski

The Daily Show and Philosophy

Edited by Jason Holt

Lost and Philosophy

Edited by Sharon Kaye

24 and Philosophy

Edited by Jennifer Hart Weed, Richard Davis, and Ronald Weed

Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy

Edited by Jason T. Eberl

The Office and Philosophy

Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski

Batman and Philosophy

Edited by Mark D. White and Robert Arp

House and Philosophy

Edited by Henry Jacoby

Watchmen and Philosophy

Edited by Mark D. White

X-Men and Philosophy

Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski

Terminator and Philosophy

Edited by Richard Brown and Kevin Decker

Heroes and Philosophy

Edited by David Kyle Johnson

Twilight and Philosophy

Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski

Final Fantasy and Philosophy

Edited by Jason P. Blahuta and Michel S. Beaulieu

Alice in Wonderland and Philosophy

Edited by Richard Brian Davis

Iron Man and Philosophy

Edited by Mark D. White

True Blood and Philosophy

Edited by George Dunn and Rebecca Housel

Mad Men and Philosophy

Edited by James South and Rod Carveth

30 Rock and Philosophy

Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski

The Ultimate Harry Potter and Philosophy

Edited by Gregory Bassham

The Ultimate Lost and Philosophy

Edited by Sharon Kaye

Green Lantern and Philosophy

Edited by Jane Dryden and Mark D. White

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Philosophy

Edited by Eric Bronson

Arrested Development and Philosophy

Edited by Kristopher Phillips and J. Jeremy Wisnewski

Inception and Philosophy

Edited by David Kyle Johnson

Copyright © 2012 by John Wiley and Sons. All rights reserved

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit us at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Inception and philosophy : because it’s never just a dream / edited by David Johnson.

p. cm.— (The Blackwell philosophy and pop culture series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-118-07263-9 (pbk.); ISBN 978-1-118-16889-9 (ebk.); ISBN 978-1-118-16890-5 (ebk.); ISBN 978-1-118-16891-2 (ebk.)

1. Inception (Motion picture) I. Johnson, David (David Kyle)

PN1997.2.I62I57 2012

791.43’684—dc23

2011028933

For Zorro, who kept me company through the entire editing process. There will never be a dog better than you. May you always live on in my dreams.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Dream Team

The dream that is this book would not be possible without a great many people. It is a shared dream.

I wish to thank the contributing authors for their tireless efforts and philosophical architecture. Like Ariadne, they designed the dream—I just filled it with my subconscious. Hopefully, it didn’t turn on them too severely.

My thanks also go to Connie Santisteban, at John Wiley and Sons, for her hard work and dedication. Like Arthur, she makes sure everything runs smoothly. This shared dream wasn’t possible without her. Likewise, I would like to thank all the folks at Wiley who work behind the scenes to make this series possible. They are the Saito to my Cobb; their giant bankroll made this book possible. If only I could get them to buy me an airline.

Last, I wish to thank my good friend and colleague William Irwin, for his patience, incredible feedback, and dedication to the cause. I’m very glad, my friend, that we have the shared dream of incepting the public with knowledge of philosophy.

THE EDITOR’S TOTEM

An Elegant Solution for Keeping Track of Reality

I know, I know. An editor’s note. Who cares, right? Wrong! Don’t skip it. This is important stuff. If you care about understanding Inception, and this book, you’ll want to hear me out.

Editing this book wasn’t easy. Inception is so ambiguous, I had to worry about whether the contributing authors interpreted, and thus would speak about, the movie in the same way. One problem, in particular, kept popping up around every corner like Cobol agents in Mombasa. How much of Inception is a dream? Is the end a dream? Is everything after Yusuf’s basement a dream? Could the whole movie be a dream? If I wasn’t careful, the book could have ended up looking like it was about two or three different movies.

So I came up with an “elegant solution for keeping track of reality.” Throughout the book, the authors refer to the world in which the inception is planned—the world in which Mal jumps from the window, where Cobb is on the run, meets Ariadne, and doesn’t wear his wedding ring anymore—as the real world. The italics are important—they indicate a title, not a description. By the use of the italicized phrase, the authors will not assume that the real world actually is the real world (notice, no italics that time). That way, when we need to ignore the issue, we can; and when the issue is important, we can concentrate on it.

Now, that’s all you need to know to start reading the book. But if you want to know why we can’t just assume that the real world of Inception actually is real, and you want to gain a much deeper understanding and appreciation of the movie, continue reading.

How much of Inception is a dream? Most people think the answer lies in an event just beyond our reach. Does the top fall at the end of the movie after the screen cuts to black? If it does, then Cobb is awake; if it doesn’t, then Cobb is still dreaming. A careful examination of the film, however, shows us that this is not the case.

First of all, Cobb’s totem is extremely unreliable as a dream detector. Arthur specifically points out, when telling Ariadne about totems, that they work only to tell you that you are “not in someone else’s dream.” So even if the top falls, Cobb could still be in his own dream. Totems have this weakness because, if the dreamer knows how the totem behaves in reality, the dreamer could dream that it behaves that way; and obviously the owner of a totem knows how it behaves in reality. This is why you don’t want anyone else to touch your totem. If anyone gets a hint of how it is supposed to behave, they could dream that it behaves that way, and then your totem couldn’t tell you that you are not in their dream world.

Despite all this, Cobb tells Ariadne, specifically, how his totem works. When she asks if the concept of a totem was his idea, Cobb says, “No . . . it was Mal’s actually . . . this one was hers. She would spin it in the dream [and] it would never topple. Just spin and spin.” So the top can’t tell Cobb that he is not in Ariadne’s dream; she knows how it works. And in fact, since she is the architect of all the dream layers in the inception, couldn’t she have (even inadvertently) worked the law “All tops fall” into the very physics of the dreams she designed? How could spinning his top ever tell Cobb that he has left the dream layers of the inception?

And wait . . . what was that? Look at that quote again. The totem was Mal’s? Well that’s just great! Sure, Cobb thinks Mal is dead; and if she is, then he doesn’t have to worry about being in her dream. But Cobb thinks she’s dead because he believes the world in which Mal threw herself from the window (the real world) is real. The only way he could come to that conclusion, however, is by spinning the top and watching it fall—but wouldn’t that be circular reasoning?

Besides, who doesn’t know that tops fall after they are spun? We have no idea how Arthur’s die is weighted, or how Ariadne’s chess piece is supposed to work. But if Cobb spun his top in anyone’s dream, wouldn’t they dream that it fell? So sure, if the top did keep spinning, after the screen went black, that would tell us Cobb is still dreaming. But the top falling wouldn’t tell us anything!

This line of reasoning brings up another problem. Forget the end of the film. Think about the beginning and the real world that most of the first half of the movie takes place in—the world where Mal jumps out the window, Cobb is a fugitive, the inception is planned, and the main characters meet. Think about when Cobb and Mal first reentered this world, after leaving Limbo. How could they tell it was real? The top couldn’t help, since they both knew how it works; either one of them could have been the dreamer. So how could they tell that world was real? The fact is, they couldn’t. There was no way to prove one way or the other. In fact, that was Cobb’s problem. There was no way to convince Mal that world was real, and that is why she ultimately threw herself from the window. Now, since that world didn’t start to crumble as soon as Mal “died” in it (like the Japanese Mansion dream started to crumble as soon as its dreamer, Arthur, died in it), it’s safe to conclude that world was not Mal’s dream. But it could still be Cobb’s dream. And if it is, Mal is not dead. She didn’t commit suicide; she was right. They were still dreaming, and she woke up.

Sure, it’s possible Cobb and Mal were still dreaming—but is it reasonable to think they were? Yes! If you pay careful attention to the movie, you will see that it is ambiguous throughout. For the same reasons that the end of the movie might be a dream, the entire movie might be a dream. Let me elaborate.

Whether the top keeps spinning at the end of the movie is an issue because it’s not clear whether Saito and Cobb make it all the way back to the real world, after exiting Limbo.1 Why is this not clear? For one thing, it’s never clear. Even when one dream ends, Cobb is always concerned that he merely dreamed that he awoke. That’s why he’s always spinning his top. But specific elements of the film give us reason to suspect that Cobb and Saito didn’t make it back. Think about this: What happens to someone when they exit Limbo? Where do they go? The two clearest examples we have are Fischer and Ariadne, who both exit Limbo by falling off a tall building. Where do they go? Not out to the real world! They go one level up, to the third layer of the shared dream—the snow fortress. (They have to ride the kicks back up to the first layer.) So when Cobb and Saito exit Limbo, wouldn’t they go up to that third layer too? If so, wouldn’t it have been long abandoned by then? (The other characters make it back up to the first level, while Cobb and Saito’s bodies lie motionless in the van.) Given this, wouldn’t one of them have simply remade that layer based on their own expectations—to find themselves on a plane, landing in California?2

You might think this is inconsistent with the facts of the film, but it says nothing about what happens to someone upon arriving at an abandoned dream level, or whether or not such a thing is possible. We know, at least, that a dreamer exiting a dream layer does not necessarily make it collapse immediately; we learn this early on in the film, when Arthur exists his Japanese Mansion dream and it continues. So it is possible to inhabit a dream layer, without a dreamer. Arthur even tries to keep Saito under, to keep the dream going. If he had been successful, who knows how long that dream could have continued, or if it would have become Saito’s or Cobb’s dream.

So, think again of the end of the film. If that third snow fortress dream level was empty when Saito arrived,3 why wouldn’t he dictate a new architecture for that level with his expectations? And, once Cobb arrived, why wouldn’t he populate it with projections of his subconscious—his team and his family? They were under very heavy sedation, and according to Cobb and Yusuf, it wasn’t going to wear off until after they spent a week on the first layer of the dream (which was six months on the second level and ten years on the third). And the other dreamers made it back up to that level before even an hour had passed in it. Even after exiting Limbo, Saito and Cobb could have almost ten years to live on that third level before the sedative even begins to wear off.

Is it reasonable to worry that Cobb and Saito didn’t make it back to the real world after exiting Limbo? Of course it’s reasonable—that’s why so many people care whether the top falls at the end of the film. But as we listen to Cobb recount his and Mal’s story to Ariadne, we realize a very similar problem comes up for them—one where we don’t even have to worry about what happens if one arrives at an abandoned dream level.

Cobb and Mal entered Limbo by experimenting with multilayered dreaming. As Cobb recounts to Ariadne,

We were working together. We were exploring the concept of a dream, within a dream. I kept pushing things, I wanted to go deeper and deeper . . . when we wound up on the shore of our own subconscious [Limbo], we lost sight of what was real.

To exit Limbo, they laid their heads on the train tracks—and woke up on the floor of some house, hooked up to a “dream machine” (PASIV) briefcase, married with two kids. But if their exit from Limbo was like every other, that floor was only one level up—the deepest layer of a multilevel dream, just above Limbo. If so, their fifty years in Limbo was long enough for them to forget this fact, or what the real world was even like. So, even if that world is not real, it’s no wonder that Cobb believes it is. Sure, Mal believes it is a dream only because Cobb incepted the idea into her in Limbo. That doesn’t mean, though, that Mal’s belief is false. She might be right, and if she is, she didn’t commit suicide—she woke up!4 If the sedative Cobb and Mal used is nearly as potent as the one used on the airplane, Cobb could be stuck on that level for ten years before he even has a chance to wake up in the real world. Who knows? Cobb and Mal might not even have kids in the real world. They might not even be married; they might have been just exploring the possibility through shared dreaming.

In fact, it seems that Christopher Nolan, the film’s writer and director, leaves us some subtle clues to suggest that it is indeed possible that the real world is only a dream.

Through his conversations with Ariadne, Yusuf, and others, we learn that Cobb can’t dream anymore unless he hooks into a PASIV device, and that he does so every night. This is, apparently, how he sleeps. Could it be that he can’t sleep or dream without the machine because he is already asleep and dreaming?Consider the scene in which Mal jumps from the window. Cobb navigates through the room that Mal has trashed, and looks out the window. She is on the opposite ledge, in the open window of another room in the hotel.5 How did she get there? Wouldn’t she have inched out on the ledge, away from their hotel room window and thus been on the same side of the building as Cobb? Isn’t Mal being on the opposite ledge just the kind of inexplicable thing that happens when dreaming?In Cobb’s dream in the basement, as he sees images of her laying her head on the train tracks in Limbo, Cobb’s projection of Mal tells him, “You know how to find me. You know what you have to do.” She says this again, as Ariadne finds him reliving his memories. If the real Mal was right and they were dreaming, Cobb merely has to commit suicide to find her. Is Cobb’s projection of Mal calling him to wake up from the dream of the real world—by committing suicide—so he can find the real Mal “up above”?Consider the chase scene in Mombasa. When Cobb jumps out the bar window, a Cobol “Businessman” is waiting for him and says, “You’re not dreaming now, are you?” Yet the chase has dreamlike qualities. Notice, in the overhead shots, how much Mombasa appears to be a maze, a labyrinth—just like Ariadne designs for the Fischer inception. Notice also how businessmen continually appear, around every corner, in just the right place, and for no reason. As the chase begins, Cobb eliminates the two who are chasing him; but as soon as he turns to run, two more are inexplicably right on his tail. When he tries to run out of the restaurant, a businessman literally appears out of nowhere to tackle him from the side. And how about the company they work for—Cobol?6 Isn’t “Cobol” just a little too similar to “Cobb”? Is he chasing himself?7 And what about that restaurant waiter, who won’t get him a “café,” but insists on drawing attention to him? And what about when he tries to escape between the two buildings, and the walls literally close in on him? Aren’t these the kinds of things that happen while one is being chased in a dream?Fischer’s subconscious is trained, when Arthur’s research shows that it should not be. Could it be trained, because in attacking Fischer, they are actually attacking Cobb—because it’s all just Cobb’s dream?When Ariadne enters Cobb’s memory of the night Mal jumped, why does she step on the glass just as Cobb did? Is it because, as a projection in Cobb’s dream, she is Cobb?Consider the beginning of the movie, when we see Cobb talking to the elderly Saito in Limbo. Saito spins the top, and then we flash back to Cobb speaking to Saito as a young man in Arthur’s dream. We then spend the rest of the movie getting back to where we started—Cobb talking to the elderly Saito in Limbo. And, we see, the top is still spinning; it was, in a way, spinning the whole movie! Could this be a symbolic clue, left by Nolan? After all, when the top spins, but doesn’t fall, aren’t we in someone else’s dream?Similarly, the running time of Inception is exactly 2:28 (in hours and minutes). The song the dreamers use to signal the end of a dream is Edith Piaf’s “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien,” the original recording time of which is 2:28 (in minutes and seconds). Another subtle clue? When the song is done, the dream is over.And what is the deal with the dream share technology? Not only do we not know how it works, but it doesn’t even make sense. Controlling dreams . . . through the arm? The technology working inexplicably is what we would expect if it is just a part of a dream. Not so much, if it is supposed to be technology that could exist in reality.8Of course, you can explain all of this away. Maybe Cobb can’t sleep or dream because he is addicted to the dream machine. Maybe Mal rented another hotel room, across the way, and went to it after she trashed the other. Maybe Cobb’s projection of Mal is calling him back to Limbo, not back to reality. Maybe Cobb is just unlucky when it comes to Mombasa chases. Maybe Fischer had covert training, and the “movie long spinning top” is just an artifact of the flashback. Maybe the film ending at 2:28 signals that it’s time for us to return to reality. Maybe Cobb’s memories never change. Maybe a dream briefcase emits some kind of “psychic field” that synchronizes all unconscious brains in the vicinity. Maybe you can’t enter layers once they are abandoned, and Saito and Cobb did make it back to the real world. Maybe Cobb and Mal didn’t use heavy enough sedatives for stable multilevel dreaming, and their suicide in Limbo woke them all the way back up. Maybe, in fact, every dreamlike element of the real world is just a way to hint at the fact that Cobb is losing his ability to distinguish dreams from reality. Maybe I’m just anomaly hunting, seeing clues where there are none! I am not arguing that the “Full Dream” interpretation is the right one. I’m pointing out that it is a legitimate, consistent interpretation of the film. (In fact, as we will see, these are not the only clues.)9

So you can see the problem. A first viewing of the film leads one to believe that the real world—the world in which Mal jumps from the window and in which the inception is planned—is the real world. A deeper look reveals that this might not be the case, however. In fact, the entire movie might be a dream.

It will be helpful, then, to start right from the first chapter by thinking about the issue of how much of Inception is a dream. So, stave off your temptation to go watch the movie again and dive right into Inception and Philosophy.

NOTES

1. There is even an issue as to whether they exited Limbo at all. But since Limbo is never as populated as the world is in the final scenes in the movie, I think we can assume they at least made it out of Limbo.

2. Besides, even if they did make it back up to the first level, their bodies are strapped into a van that is submerged in water. So, even if they did make it out of Limbo and back to the first level, it seems that they would just die again and fall right back down into Limbo.

3. Since Saito had the gun in Limbo, I’ll assume he shot himself first. Since Cobb has the same expectations, if Cobb arrived first, the story works out about the same.

4. Maybe in the real world, but maybe just in another layer of dreaming.

5. If you look behind Mal, you will see the interior of the room is the same as the one Cobb is in—notice the couch and the lamp, among other things. It’s just that Cobb’s room is trashed. She is not in another part of their suite; she is in the window of another room.

6. Interestingly, the name of Saito’s Company is “Proclus Global,” and Proclus was a Neo-Platonist philosopher (a.d. 412–485) of minor fame, who played a key role in keeping Platonic philosophy alive by heading the Platonic Academy in Athens. I considered the possibility that this was another subtle clue that Cobb is dreaming, and looked at Proclus’ philosophy. But, alas, I found nothing—although I don’t think Nolan chose the name coincidentally. It must be symbolic of something else. Nolan likes symbolic Greek names. Ariadne helped Theseus through the labyrinth to slay the Minotaur. Perhaps Nolan considers Saito to run a company of “cutting-edge thinkers” like Proclus did.

7. Actually, Nolan spoke to this possibility and dismissed it in an article in the January 2011 issue of Empire magazine titled “Christopher Nolan Made Our Minds the Scene of the Crime.” When asked whether the name “Cobol Engineering” is a giveaway that the whole plot’s a subconscious fabrication since its first syllable matches Cobb’s name, he said, “That unfortunately I would have to confess is definitely not the case. For legal reasons I had to rename Cobol Corporation about ten times. So that one I can shoot down as being not indicative of anything in particular.” One wonders, however, despite his original intention—could it still be a clue? For more on whether an author’s original intent sets the meaning of a film, see Ruth Tallman’s chapter in this volume.

8. This last point deserves some elaboration. It could be that an aside about how the technology works would just get in the way of the story, so Nolan left it out. This is actually how my favorite modern sci-fi television show, Doctor Who, handles such things. It simply explains away funky technology and time travel paradoxes by saying “It’s wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey stuff,” and moves on. Unlike Star Trek fans, most Doctor Who fans care about the story and characters, not the technical specifics, so this seems perfectly acceptable. But the problem with Inception’s dream technology goes a little deeper. How the dream share technology works is not only unexplained, it’s inexplicable. Dreams are caused by brain activity, and for a device to synchronize a group of people’s dreams, it would have to make their brains’ neurons fire in similar ways. Perhaps the machine could find some arm nerves to hook into, but synchronizing brain activity with arm nerves would be like trying to program a computer by using only the “shift” key. There is no way to control the mass action of the brain through the arm.

9. For more such clues, see Ruth Tallman’s and Jason Southworth’s chapters in this volume.

INTRODUCTION

Plato’s Academy Award

Inception didn’t win the 2010 Academy Award for Best Picture. But if they gave an Oscar for philosophical depth—call it Plato’s Academy Award—Inception would have taken home the statue (which would look like Rodin’s The Thinker). Indeed, no film in recent memory raises philosophical questions quite like Inception.

The screen cuts to black before we see whether the top falls. If we can’t know whether Cobb is dreaming, can we know that we ourselves are not dreaming? And if we can’t, how exactly should we deal with the angst such uncertainty brings? This problem has been considered by philosophers as far back as Plato (c. 428–347 bce), and it raises questions about Inception itself. If we can’t know whether Cobb is dreaming, can we really know how much of the movie is a dream? Maybe Cobb is still in Yusuf’s basement. Maybe Mal was right, and the whole movie is a dream! When it comes to works of art, is there even a way to settle such matters and determine what Inception means?

What if someone offered you a life in Limbo? Would you take it? Imagine living in a world that you control, where you can have any experience you want: a utopia. Sure, they aren’t real experiences—but what if you didn’t know that? What if, like Mal did in Limbo, you thought it was real? Would you take it then? Or would there be something pitiful about being a prisoner in Limbo, forced to think that your dream was real? Would you really want to live in Limbo anyway? Is a utopia even possible? If not, why do we strive toward one? Perhaps because it’s important to dream?

What about inception itself? You might think it’s impossible, but isn’t it just implanting ideas in other people’s minds in a way that makes them think they came up with the idea themselves? Isn’t that a big part of what advertisements, news media, songs, television shows, preachers, teachers, and even movies like Inception do? In fact, Inception seems to be an allegory for moviemaking—Cobb is the director, Eames is the actor, Yusuf is special effects. Does this mean that movies are as dangerous, and as immoral, as inception? Does real-world inception violate our free will?

What exactly are dreams? Do they really occur while we sleep? Might they occur in another world? Is it possible to act immorally in our dreams? What exactly is a mind, and could we really share ours—share our dreams? In Inception, time moves slower the deeper you go into multilayered dreams. Even in reality, though, dreaming messes with our sense of time. What might our dreams tell us about the nature of time itself?

Cobb, Saito, and Mal are all asked to take a leap of faith. Mal leaps twice, once right out a window. Saito, too (it seems). Cobb does not. He “knows” what’s real. So when, if ever, should we take our own leaps of faith?

The questions don’t stop there. Regret, self-knowledge, paradox—unlocking Inception’s secrets with Asian philosophy. We have already designed the dream. So get out your big silver briefcase, pull out the tubes, hook them up to your arm, put your finger on the big yellow button, and get ready to tackle all these issues, and more. We are about to enter the dream world of Inception.

PART ONE

WAS MAL RIGHT? WAS IT ALL JUST A DREAM?:MAKING SENSE OF INCEPTION

CHAPTER 1

WAS IT ALL A DREAM?: WHY NOLAN’S ANSWER DOESN’T MATTER

Ruth Tallman

Your world is not real. Simple little thought that changes everything. So certain of your world, of what’s real. Do you think [Cobb] is? Or do you think he is as lost as I was?

—Mal

Inception is anything but straightforward. If nothing else, the fact that the final scene cuts to black before we see whether the top falls leaves the movie open to many interpretations. Of course, figuring out whether Cobb is still in a dream is not the same as figuring out the “meaning” of the film. But the two questions are closely related, as are the questions one must ask in order to answer them. It seems that the movie doesn’t give us enough information to settle these questions, so how will we find answers? Where do we look? Is there a single answer? If Christopher Nolan, the director of Inception, told us what he thought, would that settle it?

These questions are not new, nor are they unique to this particular film. Good works of art are usually not straightforward. They challenge us, confuse us, and leave us wondering what we “should have” or “were supposed to” get from them. We worry that we might have missed the point, or misunderstood, or made a mistake in our understanding of the artwork. And when we have these concerns, when we disagree with one another about the “right” understanding of an artwork, quite often the go-to solution is to find out what the artist intended the work to mean. So, many people think, if Christopher Nolan thought the top fell, then we have our answer—the top fell. The idea here is that the artist, as the creator who gave life to the work, is privileged to determine the meaning and proper understanding of the artwork; if anyone has the authority to say, “Sorry, you just got it wrong,” it’s the artist. This position, known as intentionalism, will be discussed below.

But is this right? Does the creator of an artwork have such power over his creation? Let’s look at this question. After considering some views and arguments, I think you will agree that the answer is no. In fact, I think you’ll see that Christopher Nolan would agree as well.

The Major Interpretations

Determining whether or not the top fell at the end of the movie should, it is believed, indicate whether Cobb and Saito made it out of Limbo. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. Remember when they went to that basement full of men who shared forty hours of dream-time every day? Cobb tried Yusuf’s heavy sedative, and the dream was so deep that Cobb spun his top in the bathroom to make sure he had come out of the dream. But if you recall, he knocked the top over before it fell on its own. The whole rest of the movie could be a dream!

In fact, the entire movie could be a dream. After all, Mal and Cobb entered Limbo while “exploring the concept of a dream within a dream.” What assurance do we have that when they exited Limbo, they didn’t simply rise into a second or third layer of dreaming—like Ariadne and Fischer did when they exited Limbo at the end of the film? Consider that after Cobb assures his Limbo projection of Mal of his knowledge of reality, she retorts, “No creeping doubts? Not feeling persecuted, Dom? Chased around the globe by anonymous corporations and police forces? The way the projections persecute the dreamer?” Even part of Cobb, it seems, is not really sure the real world is real. Maybe Mal was right. Maybe she didn’t commit suicide. Maybe she woke up.

All in all, it seems that there are four major interpretations of Inception.

The “Most Real” Interpretation: Cobb and his crew exist in waking time except for when we are clearly told they are entering dream states. Cobb’s wife, Mal, is dead, having killed herself as she tried to “wake up” from her real life, which she believed was a dream. The movie ends with Cobb and Saito exiting Limbo and Cobb finally able to return home to his children in reality.

The “Mostly Real” Interpretation: Just like the most real interpretation, except that Cobb and Saito do not fully awake into reality, but into some other part of Limbo or some other dream. Thus, Cobb does not make it back to his children in reality.

The “Mostly Dream” Interpretation: What Cobb thinks is reality is reality, including Mal’s death. However, when he tries out Yusuf’s heavy sedative in his basement, he gets trapped in a dream that is the rest of the movie.

The “Full Dream” Interpretation: The entire movie is a dream, which takes place on several different dream levels, all in Cobb’s head. When Cobb and Mal woke up from Limbo, they only woke up into a layer of dreaming they had created to enter Limbo in the first place.1 They spent so long in Limbo that they forgot, and only because Cobb had incepted Mal in Limbo did Mal think it was a dream, attempt suicide, and wake up. (Perhaps she woke up in reality, perhaps in another layer of dreaming.) None of the other characters are anything but projections of Cobb’s subconscious. Even if Cobb did return to what he thought were his real children, in the real world, he is still only dreaming.2

So which interpretation is correct?

Clues from the Work

One method used to determine which interpretation of an artwork is “correct” involves an internal analysis of the work—what clues does the work itself offer? Sometimes the work gives us a pretty clear-cut answer, but a blessing and a curse of Inception is its ambiguity. Proponents of the Most Real view will point out that Cobb’s children, Phillipa and James, are played by actors who are two years older in the final scene, and that their clothing is also different in the last shot, lending credence to the view that the children have aged and Cobb really has made it home.3

Defenders of the “Mostly Real” hypothesis will argue that the children may only dress differently and look older because Cobb expects them to, and that his expectations determine the content of his dream. In addition, we never see Cobb or Saito commit suicide in Limbo, and the final sequences of the movie seem dreamlike (the film is very slow and jumps from scene to scene with no explanation). Last, the top seems to spin for much longer than is natural.

Proponents of the “Full Dream” hypothesis will point to the many dreamlike elements that the real world possesses. Cobb himself informed us, through a conversation with the dream architect, Ariadne, that a way to know that you’re dreaming is that you can’t explain how you got to your present location. We see such jumps quite often in the real world, including when Cobb mysteriously enters his father-in-law’s classroom in Paris without opening the door. In this same scene, Cobb’s father-in-law, Miles, implores him to “come back to reality.” Of course, we might be meant to take that as a metaphorical reality check. And maybe Cobb opened the door so quietly that Miles didn’t hear it. But wait a minute—how did Mal get to the ledge across from the hotel room she and Cobb frequented? Are the two ledges connected? Who’s to say? That’s actually the problem, right?4 When two careful viewers struggle with the same data and cannot agree on an answer, chances are that one of them is simply getting something wrong. But that’s not what we’re dealing with here. We’re dealing with thousands of viewers, many of them very careful, repeatedly studying the work and struggling to find “the answer.” Yet disagreement persists. It seems that Nolan simply has not given us enough information to determine “the correct understanding” of the film. Nolan himself addressed this issue in an interview. After acknowledging how many viewers have asked him for “answers” regarding the correct understanding of the film, he says:

There can’t be anything in the film that tells you one way or another because then the ambiguity at the end of the film would just be a mistake. It would represent a failure of the film to communicate something. But it’s not a mistake. I put that cut there at the end, imposing an ambiguity from outside the film.5

What Nolan Says

So an internal analysis tells us that the film is ambiguous, and Nolan says he made it that way on purpose. Yet Nolan claims to have an “answer” to the meaning of the film. He says:

I’ve always believed that if you make a film with ambiguity, it needs to be based on a sincere interpretation. If it’s not, then it will contradict itself, or it will be somehow insubstantial and end up making the audience feel cheated. I think the only way to make ambiguity satisfying is to base it on a very solid point of view of what you think is going on, and then allow the ambiguity to come from the inability of the character to know, and the alignment of the audience with that character.6

Clearly, Nolan thinks part of the magic of an ambiguous artwork is that the audience, like the characters, and like real-life human beings, must decide what to believe in the face of incomplete evidence. A work of art from a God’s-eye view, in which there is no question about how events are to be understood, rings far less true than a work that forces us to make decisions without full knowledge. And this is part of the beauty of Inception. Yet many viewers are still wedded to the idea that there is an answer, a secret to be unlocked, and that the answer lies in Nolan’s intention when he created the work. Even if he refuses to tell us what it was, these viewers feel, since Nolan intended a particular interpretation when he created the film, that’s the right answer and any view that runs contrary to that is incorrect.

Why We Shouldn’t Care What Nolan Says

Again, figuring out the “meaning” of Inception is not the same thing as figuring out how much of the movie is a dream. The meaning question, and how it relates to the dream question, is an entirely different issue. But what philosophers have said about meaning, and how to grasp the meaning of art, can help us determine how to interpret the plot of Inception.

Many philosophers accept intentionalism, the view that the artist’s intention determines the meaning of the artwork.7 But I think that such an approach fails, for three reasons. First, the intentionalist view leaves us with an epistemic (knowledge-related) problem regarding many artworks; many end up either having an unknowable meaning or no meaning at all, both of which are quite counterintuitive conclusions. Second, intentionalism forces us to understand artworks as interpretively static, when they don’t seem to be. Third, intentionalism is inconsistent with the view that the concept of art is a social convention that, properly understood, means that artworks are the collective property of the art world.

The Epistemic Problem

This objection stems from the problem that if the meaning of an artwork is rooted in the intention of the artist, we are left with an interpretive hole regarding many works of art. Nolan tells us that he has an answer regarding Inception, but that he plans to keep it a secret. This means that if Nolan gets to set the meaning of the work, the rest of us will simply never know the “right answer” regarding the way we ought to interpret the film. Now, maybe one day Nolan will crack and give us his answer (I doubt it), but what’s worse is that many artists report that they simply did not intend any particular meaning when they created their works, arguing that their only intention was for each viewer to find her own meaning in the piece (J. R. R. Tolkien made this claim regarding The Lord of the Rings in the introduction to that work).8 Regardless of that intention, if artworks really obtain their meaning through artist’s endorsement, we’re forced to conclude that these works are simply meaningless, because their artists didn’t see fit to give them one. And that doesn’t seem right.

Another problem is that some artists appear to change their interpretive account of their works over time, perhaps because they themselves are unsure of the meaning or perhaps because they perceive some benefit from rewriting their account (maybe to accord with a particular political agenda or to cash in on a new trend). In fact, they may even change their mind about how they think the work ought to be understood, or come to view it in a new way. (For instance, Christopher Nolan claimed in an interview that he never detected the connections between filmmaking and the dream-sharing technology in the film—the relationship has to do with simultaneous creation and observation—until it was pointed out to him by his brother.)9 Regardless, these types of cases raise further concerns regarding the intentionalist view. Do we really want to say that the meaning of artworks can change at the whim of the artists but that they cannot be changed for any other reason? This gives a strange amount of power to the artist and runs contrary to a social understanding of art.10 (We’ll talk more about that below.)

Not to pile on, but some works of art are of unknown authorship, making their meaning forever unknowable on this account. The gravity of this problem should be clear when you consider that many portions of the Bible—certainly a work of art, whether or not you believe it to be divinely inspired—are of unknown or disputed authorship. And even those works with known authors typically do not come packaged with an authorial account of meaning, which leaves the majority of viewers, who lack knowledge of the author’s intent, in the dark about the meaning of the work. The intentionalist view forces us to conclude that all of those viewers simply cannot know the meaning of the work or, if they do, they merely lucked into it and don’t know that they know it. The epistemic problem with the intentionalist view, then, is that many artworks—including Inception—are either meaningless or are interpretive mysteries.11 And this is quite counterintuitive. Most of us believe that we can derive meaning from a work, even if we do not know what interpretation the artist had in mind, and we don’t think the meaning we derive is in some sense wrong, or flawed, if it doesn’t accord with the artist’s intentions. A position that commits us to believing that most viewers cannot know the meaning of most works of art is therefore one that ought to be rejected.

The Interpretively Static Problem

Setting aside the epistemic problem, even if the artist’s intended meaning were knowable in all cases, the intentionalist view would still face the problem of forcing us to the position that artworks are interpretively static. On this view, once the artist has set the meaning of the work, that meaning is fixed for the life of the artwork. This view thus denies one of the features that we tend to value about art. It is generally held that one of the marks of a great work of art is that it continues to be relevant to audiences long after its original context has faded into history, and we tend to fault works that quickly become “dated.” Sometimes modern viewers will read an interpretation into a work that the artist could not possibly have intended. There is no way that Sophocles intended for Oedipus Rex to be read with a Freudian psychoanalytic spin, but do we want to say that such an interpretation is wrong because the author didn’t intend that interpretation? On the contrary, it is typically held that the power and immediacy with which Oedipus Rex continues to hit new readers is a mark in its favor, rather than an indication that all of us today are simply involved in a huge misunderstanding of the work.12

Despite its success, it is too early to tell whether Inception will stand the test of time, and if our great-grandchildren will be arguing about whether or not the top fell. But if viewers are still watching and trying to understand this film in fifty years, it is quite reasonable to suppose that those future audiences will find meaning in the work, connecting it to events or perhaps new ways of thinking or new understandings of dreams and the subconscious that Nolan could not possibly have anticipated. Do we throw out those views as incorrect, and insist that the only way to know the work is to situate it rigidly in the context of its original creation? This runs counter to a fluid understanding of art, one that allows the audiences to impact future understandings of the work, just as the work impacts the audience’s future understanding of their world. If we value the ability of an artwork to continue to exist as a dynamic piece, immediate and powerful to ever-changing audiences, we cannot privilege the author with the ability to set the work’s meaning for all time.

The Collective Ownership Problem

A third reason why we should believe that artists lack the authority to impose a singular meaning on a work stems from the very definition of art as a social convention. Some philosophers argue that artworks must be understood in relation to other artworks. This view requires a clear rejection of the intentionalist view of artwork meaning because, in this view, the meaning of a work comes partially from other works, rather than from the artist. For instance, think of the way music and lighting cue you to anticipate a particular kind of narrative turn as you watch Inception. We experience Pavlovian responses to ominous music, such as the “drum drum” in the introductory score of Inception—which, interestingly, is really just a slowed-down version of the song (Edith Piaf’s “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien”) that is used to time kicks throughout the film—because years of movie watching have primed us regarding the way we should encounter films. Think about something as basic as understanding Inception as a work of fiction in which we are invited to suspend our disbelief and suppose, for the duration of the film, that such a thing as dream-sharing is possible. This would not be the effortless transition out of everyday life that it is for us, smoothly executed as we move through the dimming aisle with our popcorn, were we not schooled in the art of film-watching.

Some philosophers place less emphasis on the role of other artworks in setting the stage for our understanding of a work, arguing instead that the concept of art exists because a subset of society, typically referred to as the “art world,” has agreed to accept the concept and to set its parameters. To put it a bit more concretely, George Dickie explains that artworks are the kind of things that are deliberately presented to an audience for the purpose of appreciation.13 This is what sets objects of art apart from ordinary objects—the art objects are the ones that have been purposely held up with an invitation to attend to them, it is hoped with positive results. On this view, there is no such thing as a private work of art. Why? Because it is the act of presenting the object to the audience that transforms it from a private sketch, musings, or experimentation into an actual work of art.

Arthur Danto takes the audience’s role with regard to artworks even further, arguing that artworks, as opposed to non-aesthetic objects, engage the audience by inviting them to “finish” the work by shading in the interpretative gaps that have been left in the artwork by the artist. After all, that is why the artists left them there—to be filled in by the audience as part of the aesthetic experience.14 When we understand an artwork as something that is by definition public in nature, the artist necessarily relinquishes control of the work when he sets it free in the world. The work then becomes the shared property of its society, and everyone is invited to impose their interpretation on it. For instance, one particularly interesting take on the movie comes from Devin Faraci, who argues that Inception is a movie about making movies.15

In this view, the artist’s possession and control of the work end when he presents it to the world as a work of art. Any restrictions regarding acceptable interpretations of the work must be built into the work itself, and to the extent that the artist leaves the work interpretively open, he has surrendered his ability to define the work. This seems to be precisely what Nolan had in mind in telling us that he purposely left the film ambiguous. He appears to be advocating the position that it is each viewer’s task to decide what to make of the confusion of information that they receive when they view the film. The right answer does not exist, and were Nolan to reveal “his” answer, it would not make a bit of difference, as the whole point of the film is for each of us to discover an answer for ourselves.

So What’s the Alternative?

My view, multiplism, says that more than one interpretation of an artwork could be valid, or “correct.” Thus, in addition to not giving the intentionalist view priority, no one view necessarily gets priority—there could be multiple, equally valid interpretations of an artwork. A common concern regarding this type of view is that it leaves artwork interpretation too open, allowing for an “anything goes” approach to artworks.

For example, we don’t want a view that says that an acceptable interpretation of Inception is that it is about a troubled guy with parental abandonment issues who dresses up in a scary cape and haunts rooftops seeking to bring bad guys to justice. We’d want to say such an interpretation is acceptable for other Nolan films, such as Batman Begins and The Dark Knight, but is unacceptable as an interpretation of Inception. Fortunately, the view I am defending does allow us to reject such interpretations, for it allows us to dismiss interpretations that are inconsistent with the facts of the film itself. As a result, the artist does have a way to restrict interpretations of his work. Our understanding of an artwork, if it is to be proper, must be consistent with the information the artist chooses to give us.16