18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

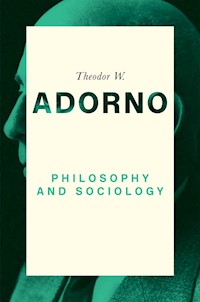

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This book provides an invaluable introduction to his historical and conceptual engagement with sociology.

Das E-Book Introduction to Sociology wird angeboten von John Wiley & Sons und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Einführung in die Soziologie, Gesellschaftstheorie, Introduction to Sociology, Social Theory, Sociology, Soziologie

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 443

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

LECTURE ONE

LECTURE TWO

LECTURE THREE

LECTURE FOUR

LECTURE FIVE

LECTURE SIX

LECTURE SEVEN

LECTURE EIGHT

LECTURE NINE

LECTURE TEN

LECTURE ELEVEN

LECTURE TWELVE

LECTURE THIRTEEN

LECTURE FOURTEEN

LECTURE FIFTEEN

LECTURE SIXTEEN

LECTURE SEVENTEEN

EDITOR’S NOTES

EDITOR’S AFTERWORD

TRANSLATOR’S AFTERWORD

INDEX

Adorno’s writings published by Polity Press

The posthumous works

Beethoven: The Philosophy of Music

Introduction to Sociology

Problems of Moral Philosophy

Other works by Adorno

Theodor W. Adorno and Walter Benjamin, The Complete Correspondence 1928–1940

Copyright this translation Polity Press 2000

First published in Germany as Einleitung in die Soziologie

Suhrkamp Verlag 1993.

First published in 2000 by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Published with the assistance of Inter Nationes.

Editorial office:

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Marketing and production:

Blackwell Publishers Ltd

108 Cowley Road

Oxford OX4 1JF, UK

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-0-7456-2971-1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

When Adorno approved the publication of a series of extempore lectures in 1962, he qualified his approval by commenting that

in his kind of work the spoken and written words probably diverged more widely than was commonplace today. Were he to speak as he was obliged by the dictates of objective discourse to write, he would remain incomprehensible. But nothing spoken by him could meet the demands he placed on a text. […] In the widespread tendency to record and disseminate extempore speeches, he saw a symptom of the behaviour of the administered world, which was now pinning down the ephemeral word, the truth of which lay in its very transience, and holding the speaker to it under oath. The tape recording is like the fingerprint of the living mind.

These words apply even more to the present publication of the last academic lectures given by Adorno, in 1968, the year before his death. They are also the only lectures by him of which a tape recording has survived. This edition therefore goes a step further than Adorno himself did when he occasionally published improvised lectures in slightly revised form. By transcribing the tape recording literally – as far as possible – this edition attempts to convey what otherwise would have been irretrievably lost: a living impression of Adorno’s lectures, however inadequately it may be reflected in print. Readers should not forget for a moment that they are reading not a text by Adorno, but a transcript of a talk ‘the truth of which lay in its very transience’.

The approach adopted in the English translation is explained in the ‘Translator’s Afterword’.

LECTURE ONE

23 April 19681

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Perhaps I may be excused for being, quite simply, delighted to see you present in such numbers at this introductory lecture. It would be disingenuous of me to conceal it – either from you or from myself. And I appreciate the confidence you show in me by being here, especially in view of certain voices which have been raised in the press of late,2 which, I am sure, have come to your notice as much as to mine. On the other hand I feel obliged, just because … [Shout from the audience: ‘Speak up!’] Well now – isn’t the loudspeaker working? – On the other hand I feel obliged, just because there are so many of you, to say a few words about the career prospects for students of sociology.

At the conference of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie3 a number of speakers complained that the Gesellschaft4 had failed to give you useful information on employment prospects for sociologists. I would point out that my colleague in Hamburg, Heinz Kluth,5 the Chairman of the Committee for Higher Education, has in fact taken great pains in that matter. However, I think I should also put before you some of the material we have in Frankfurt, however inadequate it may be, because it will help those of you who really are beginners to make a free choice on whether you want to study sociology, especially as your major subject. I have to tell you that the career prospects for sociologists are not good.6 It would be highly misleading to gloss over this fact. And far from improving, as might have been expected, these prospects have actually got worse. One reason is a slow but steady increase in the number of graduates; the other is that, in the current economic situation,7 the profession’s ability to absorb sociology graduates has declined. I should mention here something I was not aware of earlier, and have only found out since becoming closely involved in these matters. It is that even in America, which is sometimes called the sociological paradise, and where sociology does, at least, enjoy equal rights within the republic of learning, it is by no means the case that its graduates can effortlessly find jobs anywhere. So that if Germany were to develop in the same direction as America in this respect, as I prognosticated ten years ago, it would not make a significant difference. The number of students majoring in sociology has risen to an extraordinary degree since 1955.8 Let me give you a few figures: in 1955 there were 30 sociology majors, in 1959, 163; in 1962 there were 331, in 1963, 383; now there are 626. In view of this I should be professionally blinkered indeed if I were to tell you how wonderful it is that so many of you are studying sociology!

If you compare the expectations and wishes of students with the professions they actually later adopt, the results are even worse. For example – and this is very interesting – only 4 per cent of sociology students originally wanted to work at a university, whereas 28 per cent of graduates have been absorbed into higher education. In other words, the university, which produces sociologists, is also their main consumer, their primary customer. This is a situation which, making somewhat free use of the language of psychoanalytic theory, I have called incestuous [Laughter], In my opinion, this is not a desirable state of affairs. On the other hand, only 4 per cent of students (I’ll only give you a few figures, so that we don’t spend too long on these matters) originally intended to go into market and opinion research, whereas 16 per cent have actually entered that profession. By contrast, a relatively high number – 17 per cent – wanted to work in journalism, radio and television, but only 5 per cent of graduates have found employment there. With regard to industrial and company sociology, 3 per cent wanted to adopt this profession and 4 per cent have actually taken it up – a somewhat better ratio.

I won’t trouble you further with these findings, but they do show you the broad picture. Herr von Friedeburg9 has put forward the – very convincing – hypothesis that the role of sociology today is essentially educational. This gives rise to obvious contradictions between educational requirements and wishes, on one hand, and the possibility of finding employment, on the other. There is always a certain tension between these two factors, and I would think this a subject not unworthy of investigation by critical sociology. The question such a study would have to address is how it has come about in society that, in general, professions which give little satisfaction, which are taken up as a kind of sacrifice to society, which go against one’s nature, are better remunerated, socially, than those in which one follows what, in more humane times, was called the ‘human vocation’.10 Naturally, I am not speaking here about manual work but about the so-called ‘mental’ or ‘intellectual’ professions – the professions one imposes on oneself, practises against one’s own inclination. This has some bearing on the issue I am discussing. It also modifies somewhat our understanding of the educational needs within sociology. If the aim of that discipline is examined very closely, it turns out, I believe, to be something quite different to the traditional idea of education. This aim, finally, is the need to make sense of the world, to understand what holds our very peculiar society together despite its peculiarity, to understand the law which rules anonymously over us. One hears much talk about the concept of alienation – so much that I myself have put a kind of moratorium on it, as I believe that the emphasis it places on a spiritual feeling of strangeness and isolation conceals something which is really founded on material conditions. However, if I were to permit myself to use this term one more time, I would say that sociology has the role of a kind of intellectual medium through which we hope to deal with alienation. This is, of course, a very difficult question. To the extent that one seriously pursues the goal implicit in such a concept of sociology, one estranges oneself from practical purposes, from the vocational requirements of society. It is extraordinarily difficult to reconcile truly profound sociological knowledge with the professional demands to which people are subjected today. One of the difficulties of sociology – and this brings me to the problem which will concern us today – is to combine these very divergent desiderata; that is, to perform socially useful work, as Marx most ironically calls it, on one hand, and to make sense of the world, on the other. By now, these two requirements have probably become almost incompatible. Earlier – as I can still remember very well – it was the most serious and wide-awake students who were most troubled by this dichotomy. Today this fact – that the better one understands society, the more difficult it is to make oneself useful within it – has probably become a regular part of the consciousness of the intellectually progressive sector of students, and at any rate, I expect, of those in this hall today. A contradiction of this kind – that the more I understand of society, the less I am able to participate in it, if I may put it so bluntly – cannot be attributed simply to the subject of knowledge, as it might appear to naïve awareness. On the contrary, this impossible, contradictory aspect of the study of sociology is deeply bound up with the object of sociological knowledge – or, as I would rather put it – of social knowledge. Nor should you blame us, as sociologists, for being unable to reconcile these two incompatible factors. The inhomogeneous nature of sociology is something you will have to come to terms with from the outset. And you will have to try – consciously, not with a clouded vision unable to distinguish between what lies on either side of the dividing line – to acquire both the sociological skills and knowledge you need for your livelihood, and, at the same time, the insights for the sake of which, I suspect, most of you have decided to study sociology.

I know that one of the complaints which many of you – at least, I assume many of you were present on that occasion – made against the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie, for whose policies I am no longer responsible11 [Applause], was that it had failed to provide you with study guidance or a proper syllabus. Let me just say here – without wanting to minimize any omissions which may have occurred, for I am, heaven knows, no apologist for that learned body – that up to a point the discipline itself is responsible for those omissions. It is responsible in the sense that a continuity of the kind which is possible in, let’s say, medicine or the mathematical natural sciences, or even, to an extent, in jurisprudence, is not possible in sociology. It cannot be promised, nor should it be expected.

So if you expect me, in these lectures, to explain how you can best plan your course of study, I am not quite equal to the task. At this university we have taken some care to ensure that you will find out about the things which are tested in the sociology exam, or at least hear something about them. But there is no royal road in sociology which would enable you to be told what are, first of all, the subject matter of sociology, then its main fields, then its methods. Or at least my own position, that I neither can nor wish to suppress, is that sociology really cannot be carried on in that way. I am sure it is a good thing, if you want to study sociology, to start by going to an introductory lecture and, at the same time, to attend some specialized lectures on empirical techniques or special fields which interest you particularly. But I believe that you will need to find your own way into this somewhat diffuse entity called sociology. I hope you will forgive me if I also say that if one takes seriously the idea of freedom, which in the academic sphere means academic freedom, or the free choice of study – which I believe you take just as seriously as I do – then this idea also applies, to some extent, to the way students compile their courses of study. If we were to draw up a precise syllabus for this discipline and oblige you to study according to it, that would certainly make some things easier. It would put those of you who are primarily interested in exams – and I don’t think less of you for that – in a position to reach your goal with a greater degree of certainty than probably is possible under present conditions. But, on the other hand, it would bring a degree of schooling, of standardization, into this new and still relatively free subject – free because of its newness – and I think that would run exactly counter to what you are hoping to gain from your studies.

There is, here, a curious contradiction which, as far as I can see, has not been given much thought in the debate about university reform. It is a very obvious contradiction, and one really does not need to be a great thinker to bring it to light. It is that, in the efforts being made to reform the universities, two contradictory motives are at work. One is a desire to streamline the university, to make it more like a school. This would strip away, in the name of vocational training, all detours, incidentals and much else. Such a view is entirely governed by the idea of load reduction, of rationalization along the lines of technical rationality. On the other side is the demand for a university reform which does not lead by the nose, which gives priority to free and independent thought. From the way I have formulated the matter it is probably not difficult to see how I think one ought to decide, nor is it a great secret that, to me, the second way is more important. However, rather than being satisfied with making this choice, I think it more worthy of an intellectually autonomous human being to realize that the difficulty of reconciling these two demands reflects the antinomy I spoke of at the outset. Apart from dividing your time between introductory lectures, on one hand, and highly specialized ones requiring all kinds of skills and aptitudes, on the other, therefore, I cannot give you instructions on how you should study sociology. I cannot do so for the very simple reason that I believe that if this study is to perform the educational function with which it has clearly been entrusted, it is a part of that function to preserve the autonomy of those being educated, who, like Goethe’s famous mole, must ‘seek their way in the murk’.12

In such disciplines – and this applies just as much to philosophy, which I refuse to divide strictly from sociology – the situation is unlike that in mathematics, for example, as it is taught in schools. There, one advances by totally transparent steps, each of which is quite obvious, from the simple to the complex, or whatever the progression might be. Years ago I wrote an essay in Diskus on the study of philosophy,13 and I think it would apply, mutatis mutandis, to sociology as well. What I have to say is not intended to be frivolous, or to encourage anyone to go about their studies in an amateurish, indiscriminate way. It simply expresses my experience that academic study differs emphatically from school work in that it does not proceed step-by-step in a mediated, unbroken line. It advances by leaps, by sudden illuminations. If you have been immersed in it long enough, even though you may sometimes find things difficult to understand at first, something like a qualitative leap occurs, simply through the length of time you have studied the material and, above all, reflected on it, and lights up things which were far from obvious at first. Perhaps I might remind you of the short piece ‘Gaps’ in Minima Moralia,14 in which, more than twenty years ago and long before I was confronted with these so-called ‘pedagogical problems’, I attempted to define this kind of progression. And I think you would do well to move with a certain liberality or patience in the dimension I have just tried to describe. If, at every step, you do not immediately insist on finding out whether you have understood that step, but just make the leap, I think this will benefit your understanding of the whole rather than hindering it. Of course, this does not mean that you should uncritically accept the verba magistri when their meaning is far from clear to you. It only means that you should not proceed from the outset in accordance with what I am not embarrassed to call a positivistic, Cartesian model, employing a step-by-step approach. According to the theory to which I am introducing you, it is highly uncertain whether that model has any such absolute validity as was once claimed for it. That is what I have to say to you on these matters for the moment.

The purpose of an introduction to sociology – as many of you may have extrapolated from what I have been saying over the past few minutes – raises very specific difficulties, which arise because sociology is not what in mathematics is called a ‘determinate manifold’.15 Furthermore, it entirely lacks the kind of continuity which is generally supposed to be peculiar to the study of disciplines which impart ‘knowledge conferring control’, to use an expression of Scheler’s.16 This will undoubtedly seem somewhat paradoxical to those of you who are embarking on this study with a certain naïve trust and whose existence I have to assume in a so-called introductory lecture. To us hard-boiled old hands it seems less paradoxical. If one has acquired the deep-seated certainty that the society in which we live – and ultimately, despite the disagreement of some sociologists, society is the primary subject of sociology – is contradictory in its essential structure, then it is not so terribly surprising that the discipline which concerns itself with society and social phenomena or social facts, faits sociaux,17 does not itself represent such a continuity. If one were a thoroughly devious and malicious person, one might even suspect that the scientific demand for an unbroken continuity of sociological knowledge, of the kind which underlies the grand system of Talcott Parsons, for example, is itself infected by what might be called a ‘harmonistic’ tendency.18 This would mean that within the seamless exposition and systematization of social phenomena there lurks – unconsciously, of course, for we are witnessing the objective mind at work – a tendency to explain away the constitutive contradictions on which our society rests, to conjure them out of existence.

To enable you to familiarize yourselves with the ideas I shall be discussing first, I should like to recommend you to look at my book Soziologische Exkurse. This is for the real beginners among you. Read the first two chapters in particular, where these matters are not just set out theoretically but are underpinned by fairly copious material on the history of dogma.19

I imagine that many of you have come here expecting to hear, first, a definition of the field of sociology, then a division of this field into its different compartments, followed by a discussion of its methods. I would not dispute that such a procedure is possible or even that it is pedagogically fruitful. However, I cannot bring myself to proceed in that way, although I am aware that I am thereby asking rather more of you than many of you may have expected from an introductory lecture. I am also aware that by deciding not to proceed like that I am influenced by a number of theoretical positions which I can only set out for you properly in the course of these lectures. However, I do not want to present my divergent approach in a merely dogmatic way. I should like to explain why I cannot proceed as mentioned just now, or as required by so-called common sense, which, of course, scholarly consciousness is supposed to transcend but which – as can be learned from Hegel20 – is not to be despised. So I should like to begin e contrario, not by introducing you to sociology and sociological problems, but by giving you an idea of what lies ahead. I shall do so by showing why I do not believe one can proceed in sociology in the sequence: definition of academic field; compartmentalization of academic field; description of methods.

First of all, I should like to mention something very simple, which you can all understand without any prior discussion of the problems of social antagonisms. It is that sociology itself, as it exists today, is an agglomerate of disciplines which first came into existence in a quite unconnected and mutually independent way. And I believe that many of the seemingly almost irreconcilable conflicts between schools of sociology arise in the first place – although I am aware that deeper issues are also involved – from the simple fact that all kinds of things which initially had nothing to do with each other have been brought together under the common heading of sociology. Sociology originated in philosophy, and the man who first inscribed the name ‘sociology’ on the map of learning, Auguste Comte, called his first major work The Positive Philosophy.21 On a different level, empirical techniques for collecting data on individual social phenomena gradually emerged from the cameralistics of the eighteenth century, which were already active under the mercantilist system. These techniques of sociology, and the aspirations it derived from philosophy, were never really combined, but came into being independently of each other.

I do not want to overburden you in this first lecture with historical considerations, although to see how all this actually came about would not be the worst way of gaining access to sociology. All the same, if I am any judge of your own needs, I think it is better to approach the problems as directly as possible in an introductory lecture, rather than explaining at length where everything comes from. I am probably the last to be suspected of underestimating the historical dimension. As far as historical considerations are relevant, they will be covered in the introductory seminar which follows these lectures, and in the various tutorials connected with it.22 Nevertheless, I should like to say to you that this peculiar and somewhat disturbing inhomogeneity of sociology, its character as an agglomerate of disparate elements, is already to be found in Comte himself. Not explicitly, of course, as Comte was a scholar who adopted a highly rationalistic and even pedantic stance. At least on the surface he felt the need to present everything as if it had the coherence of a mathematical proof. But in this respect sociology is not so very different to philosophy: its famous texts, too, must be considered as a force-field; the conflicting forces beneath the surface of the seemingly unanimous didactic opinions, which are brought together more or less provisionally from time to time in systems or summaries, must be uncovered. With regard to Comte, it looks as if, on one hand, he subscribed quite clearly to the scientific ideal of knowledge, and that one of his great themes was to complain that the science of society did not yet possess the absolute reliability, the rational transparency and, above all, the unambiguous foundation in strictly observable facts which he ascribed to the natural sciences. In doing so he did not pause to reflect that this might have to do with the subject matter itself. For example – to give you my opinion straight away – he did not consider whether predictions were possible in sociology, or at least in the field of macrosociology, in the same way as they are possible in the field of the natural sciences in general. Of course, he gives reasons for sociology’s position as a late-comer among sciences, but he does not worry unduly about this, assuming quite naively that if only knowledge could advance sufficiently, the science of society would be formed on the model of the natural sciences, which had been so eminently successful. On the other hand, however – as I have already said – sociology for him also meant philosophy. This is a very difficult aspect of Comte, for it can be said that Comte was an enemy of philosophy above all else. In this he was the direct successor to Saint-Simon, his teacher, a sworn enemy of speculative thought, of metaphysics. Comte hoped that sociology would take over the function which, according to him, had been earlier performed by metaphysical speculation. Be that as it may, Comte, too, wanted sociology to go beyond the exploration of individual sectors, individual problems of epistemological practice, and to provide something like a guide to the proper arrangement of society. He arrived at this expectation from the very specific standpoint in which he found himself. On one hand, he was the heir of bourgeois emancipation, of the French Revolution; on the other, very much like Hegel, he was fully aware that – as Hegel was already pointing out – bourgeois society was being driven beyond itself.23 This social antagonism, felt by Comte, was precipitated in the dichotomy between the principle of order and the principle of progress, between the static and dynamic principles within sociology.24 But however that may be, on one hand, Comte espoused the outlook and the ideal of the natural sciences; on the other, he upheld a secularized philosophical ideal, in that he envisaged a situation in which society would be guided by sociology along what was, according to his theory, the correct path. You can see, therefore, how the dual nature or the ambiguity of sociology reaches right back to its theoretical beginnings. I shall say more about this, and about the original function of sociology in the narrower sense, in the next lecture.

LECTURE TWO

25 April 1968

Ladies and Gentlemen,

You will recall that I attempted in the last lecture to show you in rather abbreviated terms that the peculiarly dualistic character of sociology is already discernible where the term sociology was first introduced, in the work of Auguste Comte.

We have read in the press recently1 that the deliberations at the conference of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie, which many of you must have attended, failed to advance beyond certain antitheses existing within sociology. I believe this to be wrong because, as long as sociology remains what it was at its origin, it will not be possible to eliminate that antithesis – to resolve it, in the popular phrase. It will only be possible to give expression to this antagonism – if you wish to call it that – on the various levels at which it manifests itself. If, on the other hand, it is expected that details, and sometimes just minutiae, pertaining to this or that area of the discipline, should be presented at a congress of that kind, that seems to me to miss the point of such an occasion, which ought to give information on essential problems and not serve up detailed results. If the latter is demanded as the yardstick of such a gathering, the dispute or antagonism at issue is, in a sense, decided in advance. And that is precisely what concerns me: that the conclusion should not be preempted one-sidedly, but that the argument should be carried forward through all its stages, as far as that can be done.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!