Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: NYLA

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

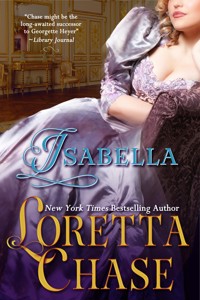

The traditional Regency classic from New York Times bestseller Loretta Chase is back…At the advanced age of 26, the independent, wealthy and imminently practical Isabella Latham has no expectation of marriage. But, good-hearted and dutiful, Isabella accompanies her two young country cousins to oversee their London debut...only to find that it's she who is attracting suitors...all of whom do seem to have quite an excess of creditors!There's the sinfully sexy Basil Trevelyan, a rake through and through, but so charming that even sensible Isabella is almost tempted. But then there's his maddeningly handsome—and maddeningly arrogant!—cousin, Edward Trevelyan, seventh Earl of Hartleigh, who has no need of Isabella's dowry; but whose adorable orphaned ward needs a mama. Could he love Isabella for herself? Isabella is too busy trying to decide whether to kiss him—or kill him!Poor, poor Isabella. What's a girl to do? But more importantly...who's a girl to choose?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 262

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1989

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Isabella

Loretta Chase

Contents

Isabella

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Isabella’s Epilogue

Also by Loretta Chase

About the Author

Isabella

by

Loretta Chase

This ebook is licensed to you for your personal enjoyment only.

This ebook may not be sold, shared, or given away.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the writer’s imagination or are used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Isabella

Copyright © by Loretta Chekani, 1987

Ebook ISBN: 9781617508516

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this work may be used, reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

NYLA Publishing

121 W 27th St., Suite 1201, NY 10001, New York.

http://www.nyliterary.com

Chapter 1

"Disappeared!" the earl repeated, in a dangerously quiet voice. "What the devil do you mean, 'disappeared'? Seven-year-old girls don't just vanish."

The thin governess trembled. She had never heard quite that tone from her employer before, and would have preferred that he shout at her, for his suppressed fury was far more terrifying. Edward Trevelyan, seventh Earl of Hartleigh, was an extremely handsome man whose warm brown eyes had often set Miss Carter's forty-year-old heart aflutter. But at the moment, the brown eyes glittered down at her with barely contained rage. And though his voice was low, the temper he so carefully controlled showed in his long fingers, which now, as he questioned her, were angrily raking the thick dark curls at his forehead.

Stammering and tearful, Miss Carter tried to explain. She'd taken Lucy to the circulating library. They'd then decided to see if they could find a ribbon to match Lucy's newest and favourite dress. Miss Carter had stopped only a moment—to admire the cut of Lady Delmont's pelisse as that grand and rather scandalous personage entered the shop across the street. Apparently, the governess had let go of Lucy's hand. Not that she actually remembered letting go—she was so sure she hadn't—but she must have, for when she looked down beside her, Lucy was gone. She had searched all the nearby shops to no avail.

Turning away from the governess in disgust, Lord Hartleigh began snapping orders to his household. He dispatched a dozen servants to comb the streets, then called for his carriage, his hat, and his cane. When the door finally closed behind him, the remaining inhabitants commenced to whispering among themselves; all but Miss Carter, who, teary-eyed and red-faced, scurried to her room.

It served him right, he thought as the carriage made its way down the street. This was what came of being so hasty as to hire a governess for his young ward. Yet Miss Carter had not seemed the least bit flighty—and she had come highly recommended. Even Aunt Clem had agreed with his choice of governess for Lucy. Well, actually, she had said, "I suppose she'll do—but it won't do, you know, Edward." Whatever "it" was. Clem had a tendency to fix you with her eye in that all-knowing way of hers and then utter cryptic pronouncements in the tone of a sybil.

Life certainly had changed when one must go to Aunt Clementina for advice, he thought ruefully. There was a time when he'd made his way across the Continent, close to Napoleon's forces, in search of information which would save English lives. But twice he'd endangered his own. He would be dead now if it hadn't been for Robert Warriner. Instead, it was Robert who was gone. News of his death had been delivered a month ago by the housekeeper's husband, along with a letter...and a seven-year-old girl.

The letter was short, and he had read it often enough to know it by heart, especially the closing lines:

It is rather a great favour I ask, my friend. But the doctors have no hope for me, and Lucy will be left alone in the world. Our housekeeper and her husband have offered to take her in, but they are hard-pressed to care for themselves, and I cannot place such a burden on them. For old times' sake, then, will you watch over my daughter as though she were your own?

Watch over her. And now the child was lost in the middle of a busy and dangerous city. Oh, Robert, forgive me, he thought.

"Mademoiselle Latham, you must trust me. I do not cut the gowns simply à la mode. I cut pour la femme. But see, how can you judge?" Nudging her recalcitrant customer along to the dressing room, Madame Vernisse continued in that sing-song of hers. "First you must try it on, and then we shall see what we shall see."

Although she obediently followed the modiste into the dressing room, everything within Isabella cried out for escape, and she had the mad urge to dash back out of the room, the shop, and London altogether. Back to Westford and the home she and her widowed mother had made with quiet, sensible Uncle Henry Latham. Life in Westford might be dull at times, and Aunt Pamela's social climbing a source of embarrassment, but there at least Isabella was not the object of constant scrutiny and speculation. Why, Lady Delmont had stared at her quite rudely, and for no other reason than that Isabella was Maria Latham's daughter. Well, let her stare. Mama may have disgusted her family by marrying Matthew Latham—a mere cit—but she was Viscount Belcomb's sister, nonetheless. And unlike her brother Thomas, Maria Latham was quite plump in the pocket. Isabella raised her chin just a little as Madame Vernisse slipped the blue silk gown over her head. And when the modiste stepped back with a little smile to admire her handiwork, Miss Latham bravely looked into the mirror.

It was lovely. It was also a trifle...shocking.

"Madame Vernisse, are you certain...?" She motioned vaguely toward her bosom, an alarming expanse of which was in public view.

"It is perfection on you," the modiste replied. "Of course the fashion is much more décolleté than this—but as I tell you, I do not cut just for the fashion; I cut also for the femme."

It was amazing what a new frock could do. The elegantly cut gown clung to her slim figure, calling attention to previously well-concealed curves. The rich blue deepened the blue of her eyes and made her complexion seem creamily luminous. Even her dingy blonde hair had taken on a golden luster. She looked, in fact, almost pretty. Not that it signified how she looked. After all, this was her two cousins' first Season. Isabella need only look well enough to appear with men in public.

Thinking of the coming months, Isabella suddenly felt weary. She would have much preferred to stay quietly in the country with Uncle Henry and Aunt Pamela Latham, her late father's brother and his wife. It was, as Mama had said, a great bore to go where one was not welcome. But Aunt Pamela wanted her eldest daughter, Isabella's cousin Alicia, to have a London Season; it was hoped the girl would find herself a titled husband. And so Mama had been persuaded to write to her estranged brother, the viscount, with a simple proposal: The Lathams would be pleased to finance a Season for the viscount's daughter, Veronica Belcomb, if, in return, Alicia Latham was also provided entry into Society. It was a bitter pill for the Belcombs to swallow, but they had little choice, as Aunt Pamela well knew.

"Barely a feather to fly with," she'd said. "Veronica's dowry is nothing to speak of—and what good is even that, I ask you, when they can't afford a Season for her?"

The blue gown was gently removed, and an emerald-green gown took its place, to be in turn replaced by a series of walking dresses, and a deep forest-green riding habit.

"You see?" said Madame Vernisse. "The colours of the sea, and of the cool forest. And so your hair glows and your eyes sparkle. Was I not correct?"

Isabella nodded agreement, but her mind was on her family and its problems. And when her ever-restless abigail, Polly, offered to run some errands while the fittings continued, Isabella dismissed her with an absent nod. To soften the blow to the Belcomb pride, Maria Latham had proposed herself as chaperone. This would save Lady Belcomb the embarrassment of being seen too much in public with a girl whose father was engaged in trade. And, of course, it would save her ladyship the expense of a new wardrobe—for it was one thing to take advantage of her only chance to see her daughter properly launched; it was quite another to be beholden to the Lathams for the very clothes on her own back. And so the offer was accepted, and Lady Belcomb had little to do but tolerate the three Lathams under her roof and smooth the way for her sister-in-law—whom society had not seen in twenty-seven years. The rest would be up to Maria.

It was unfortunate that Mama and Uncle Henry had both insisted on Isabella's coming to London as well. Of course, it was too much to expect her languid parent to be in constant attendance on a pair of "tiresomely energetic schoolroom misses," even though she had proposed herself as nominally their chaperone. The real task would fall to Isabella. And after all, they were under tremendous obligation to Uncle Henry, for had he not welcomed them into his home after Papa died, and helped them rebuild the fortune Matt Latham had speculated away? She came back to the present with a jolt when she heard the modiste's voice at her ear.

"So, mam'selle, I think we have done well for today. And by the end of the week, we shall have the others ready as well. Bon. It is a good day's work, I think." Nodding approval at her own artistry, Madame Vernisse was so pleased with herself that she even condescended to help Isabella back into her somber brown frock, although the modiste did frown as she fastened up the back and tactfully suggested that it be given—as soon as possible—to Polly. Then she hustled out of the dressing room, and promptly began scolding her assistants, who weren't looking busy enough to suit her.

Several pins had come loose from Isabella's hair, and she stopped to make repairs before leaving the dressing room. As she glanced in the mirror, she was a little disappointed to see a dowdy spinster again, and sighed. A tiny sigh echoed it, and she looked around quickly. No one was in the room but herself. Then she heard it again. It seemed to be coming from a pile of discarded lining fabric that had fallen into a corner. Evidently it had been a busy day for the modiste; normally, the shop was scrupulously tidy.

Cautiously, Isabella stepped toward the fabric. It moved slightly, and emitted a whimper. As she moved closer, she saw a tiny hand clutching a red ribbon. She lifted a corner of the fabric to find a little girl, asleep. As Isabella gently smoothed the tousled brown curls away from her face, the child, who had somehow managed to sleep through the earlier chatter in the dressing room, awoke to the caress.

"Mama?" she whispered. Then, when she realised that this was a stranger, the tears welled up in her eyes. "She's gone away," she told Isabella, and began sobbing as though her heart would break.

When Madame Vernisse re-entered the dressing room to see what had become of her latest client, she was shocked to find that young lady seated on the floor, cradling a little girl in her arms.

"And so your name is Lucy, is it?" Isabella inquired, some minutes later, after the child had been comforted and her tears bribed away with sweets. "Is that all of your name?"

"Lucy Warriner," the girl answered.

"Oh, blessed heavens. It is Milord 'artleigh's ward," cried Madame Vernisse. "They will be frantic for her. I must send someone immediatement. Michelle! Michelle! Where is that girl when you want her? Not here. Never here. Where does she go, I ask?"

"Polly will be back in a moment," Isabella replied, calmly. "We'll send her." Turning back to Lucy, she asked, "And how did you get lost in the dressing room?"

"Oh, I didn't get lost," the child replied. "I escaped."

"What did you escape from?"

"That lady. Miss Carter. My govermiss."

Suppressing a smile, Isabella continued, "I should think Miss Carter would be worried sick about you, Lucy. Don't you know it's wrong to escape from your governess? She's there to take care of you."

"Papa took care of me. He didn't get a govermiss. Even after Mama went to heaven, he took care of me himself. I don't need a govermiss. But I miss my papa." As tears threatened again, Isabella gave up her questioning and offered hugs instead.

When another quarter hour had passed and Polly had not yet returned, Isabella determined—despite Madame Vernisse's vociferous Gallic protests—to escort the child back to the earl's house herself. So it was that she emerged from the mantua-maker's shop with Lucy's hand in hers and nearly collided with a very tall, very well-dressed, and very angry gentleman.

"I beg your—" he began, irritated. His eyes then fell upon Lucy, who was attempting to hide in Isabella's skirts. "Lucy! What is this?" He glared down at Isabella from his more than six-foot height. "That child is my ward, miss," he growled. "I assume you have some explanation."

Stunned by this unexpected rudeness, and not a little cowed by his size, Isabella stared, speechless, at him. She felt Lucy's grip on her hand tighten. This was the girl's guardian? The poor child was terrified of him.

"Perhaps you would be kind enough to release her," Lord Hartleigh continued, reaching for Lucy's free hand. Lucy, however, backed off.

At this Isabella found her tongue. "I will be happy to— if in fact you are her guardian, and if you would calm yourself. You're frightening her."

Hearing the commotion, Madame Vernisse hurried to the entrance. "Ah, Milord 'artleigh. You have arrived at the bon moment. We have found your ward!" she cried triumphantly.

"So I see," he snapped. "Then perhaps you would be kind enough to tell your assistant to let me take the girl home."

Madame Vernisse looked from one to the other in bewilderment. "But Milord—"

"Never mind," said Isabella. She was shaking with anger, but endeavoured to control her voice as she bent to speak to the little girl. "Now, Lucy, your guardian is here to take you back home."

"I don't want to," Lucy replied. "I escaped."

"Yes, and you have worried Lord Hartleigh terribly. You see? He is so distraught that he forgets his manners and blusters at ladies." This last caused the earl's ears to redden, but he held his tongue, sensing that he was at a disadvantage. "Now if you go nicely with him, he'll feel better and will not shout at the servants when you get home."

"You come, too," Lucy begged. "You can be my mama."

"No, dear. I must go back to my own family, or they'll worry about me, too."

"Then take me with you," the child persisted.

"No, dear. You must go back with your guardian. You don't want to worry him anymore, do you? Or hurt his feelings?"

The notion of this giant's having tender feelings which could be hurt was a bit overwhelming for the child, but she shook her head obediently.

Isabella stood up again. Reluctantly, the little hand slipped from her own, the brown curls emerged from their hiding place, and Lucy allowed her guardian to take her hand.

"I'm sorry I worried you, Uncle Edward," she told him contritely. "I'm ready to go home now." As they began to walk to his carriage, she turned back briefly, to offer Isabella one sad little wave good-bye.

The missing Polly reappeared in time to see the earl lift Lucy into the carriage and then climb in himself. "Oh, miss," she gasped. "Do you see who that is?"

"Yes. It is Lord Hartleigh. And it is time we went home."

"A spy, you know, miss," Polly went on, hurrying to keep up with her mistress, who was clearly in a tizzy about something. "They say he was a spy against those wicked Frenchies. And they caught him, miss, you know, and threw him in prison, and he nearly died of the fever there, but he got away from them. And then came back half-dead. Laid up for months, he was. And all for his country. He's a real hero—as much as my Lord Wellington—but it's a secret, you know." She sighed. "Lor', such a handsome man. The shoulders on him—did you notice, miss?"

"Handsome is as handsome does," snapped her mistress. "Do hurry. I promised to be home for luncheon."

Lord Hartleigh had ample time to consider his behaviour during the silent ride home. After all, one could not expect Lucy to speak. She was always sad and withdrawn, and speaking to her only made her sadder and more withdrawn. It was only at Aunt Clem's that the child had shown any sign of animation. But Lucy had not been the least shy with that strange woman at the dressmaker's. Good heavens, she'd even asked her to be her mama! As he recalled the scene, he was filled with self-loathing. What an overbearing bully he must have looked!

His behaviour that day had been abominable: Cold and impatient with Miss Carter, he had gone on to make a complete ass of himself at the modiste's. But he had been turned inside out by worry—and guilt. That hour he'd spent searching the shops had seemed like months. Robert had trusted his child to him. And after less than a month, this trusted guardian had proceeded to misplace her. I take better care of my horses, the earl thought miserably.

He glanced again at Lucy. She was the image of her father, with her hazel eyes and curling brown hair, but she had none of his spirit. Not that her recent losses weren't enough to stifle the spirit of even the liveliest child. Pity for her welled up in him, and he felt again the same frustration he'd felt for weeks: He could not make her happy. Why had she run away? And what was so appealing about this dowdy young woman that Lucy wanted to go away and live with her?

Of course, that fair-haired young woman had not been the dressmaker's assistant; he should have known it as soon as she opened her mouth. He'd seen her somewhere before...at one of those dreary affairs to which Aunt Clem was forever sending him in search of a suitable wife? Or had it been somewhere else? No matter. He should have known by her dignity and poise that she was a lady. But he'd been too distraught to think clearly. He smiled ruefully. Distraught and blustering. Just as the young lady had explained so patiently to Lucy. He had simply reacted—out of fear for Lucy's safety and, it must be admitted, hurt pride. It was not agreeable for a man who'd taken responsibility for the safety of whole armies to discover that he could not adequately oversee the care of one little girl. Nor was it agreeable to see the way the child had clung to that woman, or the reluctance with which she had come to him.

But it was to be expected, was it not? Lucy wanted a mama; so badly that she would pick up strange women on the street. Well, if a mama was what was required, he would supply one. It was not pleasant to think of, but when before had he shunned a dangerous mission?

Dangerous. That was it. The woman he'd seen early the other morning, dashing across the meadow on that spirited brown mare. Good God! Lord Belcomb's niece.

Looking up timidly, Lucy saw that her guardian's face was turning red. Fearful of a scolding, she shrank farther into her corner.

Chapter 2

"Do my eyes deceive me, Freddie? Or has a new face actually entered this redoubt of redundancy, this mansion of monotony?"

Young Lord Tuttlehope looked toward the doorway where Lord and Lady Belcomb had just entered, accompanied by a nondescript blonde young woman in a modish blue gown. Blinking away his friend's literary flourishes, he responded to the few words he understood. "Matt Latham's daughter. Belcomb's niece. Got a few thousand a year."

Basil Trevelyan lifted an eyebrow.

"How few?"

"Ten or twenty. Maybe more. Matt blew up most of what he had in one scheme or another. But Henry took them in hand. Clever man, Henry. Shrewd investor."

Basil's interest increased. His topaz eyes half-closed in apparent boredom, he nonetheless watched the trio make their way through the room until they settled in a corner with Lady Stirewell and her daughter.

"Indeed. Charming girl, don't you think?"

Freddie blinked uncomprehendingly at his friend. The two had been at Oxford together and maintained a friendship ever since; yet it may safely be supposed that Lord Tuttlehope understood only a fraction of what his companion said or did. However, he made up for his slow wit with a strong loyalty.

"Barely met the girl myself," he replied. "Introduced at the Fordhulls' dinner. Sat the other end of the table. Never said a word. Don't blame her. Meal was abominable. Fordhulls never could keep a good cook."

"My dear Freddie," Basil drawled, still watching the young woman, who had embarked upon a lively conversation with the youngest Stirewell daughter, "it does not require an intimate relationship to ascertain that a young woman with an income of more than ten or twenty thousand a year must perforce be charming. And to those already considerable charms, one must add the mystique of scandal. Didn't her mother up and run off a week after her come-out?"

"Heard something about it. Never said whom she'd run off with. Six months later sends word she's married the merchant—and breeding," Freddie added with a blush.

"I thought Belcomb had washed his hands of his regrettable sister and her more regrettable spouse and offspring. Or hath ready blunt the power to soothe even the savage Belcomb beast?"

His speech earning him two blinks, Basil translated, "Is his lordship so sadly out of pocket that he's reconciled with his sister?"

The light of comprehension dawned in Lord Tuttlehope's eyes. "Thought you knew," he responded. "Bet at White's he'd be down to cook and butler by the end of the Season. Staff got restless—hadn't paid 'em in months. Then the Lathams turned up."

"I see." And certainly he did. No stranger to creditors himself, Basil easily understood the viscount's recent willingness to overlook his sister's unfortunate commercial attachment. Though he was barely thirty years old, Basil Trevelyan had managed to run up debts enough to wipe out a small country. Until two years ago, he'd relied on his uncle—then Earl of Hartleigh—to rescue him from his creditors. But those halcyon days were at an end. Edward Trevelyan, his cousin, was the new Earl of Hartleigh and had made it clear, not long after assuming the title, that there would be no further support from that quarter.

Basil had remained optimistic. Edward, after all, regularly engaged in extremely risky intelligence missions abroad, and one could reasonably expect him to be killed off one fine day soon—and, of course, to leave title and fortune to his more deserving cousin. Disappointingly, upon his father's death Edward had dutifully ceased risking his life on England's behalf, and had taken up his responsibilities as a Peer of the Realm.

"Not in the petticoat line myself, you know," Freddie remarked, "but she ain't much to look at. And past her prime. Closer to thirty than not."

His friend appeared, at first, not to hear him. Basil's attention was still fixed on the viscount's party. It was only after Lady Belcomb finally let her glance stray in his direction that he turned back to his companion, picking up the conversation as though several empty minutes had not passed.

"Yes, it is rather sad, Freddie, how the uncharming poor girls look like Aphrodite and the charming rich ones like Medusa."

Lord Tuttlehope, whose own attention had drifted longingly toward the refreshment room, recalled himself with a blink. After mentally reviewing the stables of his acquaintances and recollecting no horses which went by these names, he contented himself with what he believed was a knowing look.

"Always the way, Basil, don't you know?"

"And I must marry a Medusa. It isn't fair, Freddie. Just consider my thoughtless cousin Edward. Title, fortune, thirty-five years old, still a bachelor. Should he die, I inherit all. But will he show a little family feeling and get on with it? No. Did he have the grace to pass on three years ago, when the surgeons, quite intelligently, all shook their heads and walked away? No. These risky missions of his have never been quite risky enough."

"A damned shame, Trev. Never needed the money either. Damned unfair."

Basil smiled appreciatively at his friend's loyal sympathy. "And as if that weren't exasperating enough, along comes the orphan to help spend his money before I get to it. And to ice the cake, I now hear from Aunt Clem that he's thinking to set up his own nursery."

"Damned shame," muttered his friend.

"Ah, but we must live in hope, my friend. Hope of, say, Miss Latham. Not unreasonably high an aspiration. Perhaps this once the Fates will look down on me favourably. At least she doesn't look like a cit—although she obviously doesn't take after her mother. Aunt Clem said Maria Belcomb was a beauty—and there was something odd in the story...oh well." Basil shrugged and turned his attention once more to the pale young lady in blue. Seeing that the viscount had abandoned his charges for the card room, he straightened and, lifting his chin, imagined himself a Bourbon about to be led to the guillotine.

"Come, Freddie. You know Lady Belcomb. I wish to be introduced to her niece."

Miss Stirewell having been swept away by her mother to gladden the eyes and hearts of the unmarried gentlemen present (and, possibly, to avoid the two ne'er-do-wells who seemed to be moving in their direction), Isabella Latham tried to appear interested as her aunt condescended to identify the Duchess of Chilworth's guests. Her grace's entertainments were famous, her invitations desperately sought and savagely fought for, with the result that anyone of the ton worth knowing was bound to be there, barring mortal illness.

"Even the Earl of Hartleigh," Lady Belcomb added. "For I understand he's given up those foreign affairs and is finally settling down."

Isabella's cheeks grew pink at the mention of the name. Though a week had passed since that scene at the dressmaker's shop, she still had not fully recovered her equanimity. True, the earl had called the day after the contretemps to make a very proper, though cool, apology—to which she had responded equally coolly and properly. Lady Belcomb had absented herself for a moment (to arrange for Veronica's "accidental" appearance), and Mama, as usual, was resting. Thus none of the family had been privy to their conversation. However, the footman who stood at the door guarding her reputation had heard every syllable, and Isabella wondered what exaggerated form the drama would have taken by the time it reached her aunt's ears.

"Indeed," that lady continued, "it was most astonishing, his coming to call. But he is rumoured to be seeking a wife. And Veronica was looking well Tuesday, was she not?"

"She is always lovely, Aunt," Isabella replied. She had not missed the increased warmth in the earl's manner when Veronica entered the room. Nor, when those haughty brown eyes had been turned upon herself, had she failed to notice how he'd sized her up, appraising her head to toe and, in seconds, tallying her value at zero. Not that it mattered. It was her cousin's Season to shine. At the advanced age of twenty-six, Isabella Latham need not trouble her head with the appraisals of bored Corinthians.

"It is a pity their come-out had to be put off so late," Isabella continued, forcing the handsome and haughty earl from her mind. "For Alicia and Veronica might have been here to enjoy this with us."

"Well, well. Alicia could not be presented to society in a wardrobe made by the village seamstress."

"That is true, Aunt."

"And after all," Lady Belcomb went on, not noticing the irony of her niece's tone, "there will be festivities enough. Although this is quite a brilliant assembly—did you notice Lady Delmont's emeralds? I was not aware her husband...but then, never mind." Reluctantly, she turned from contemplation of the jewels on Lady Delmont's bosom. "Veronica will have plenty of time to shine, along with your other little cousin. It is but two weeks until their little fête."

Her niece looked down to hide the smile quivering on her lips. While the viscountess had accepted the exigencies of fate and graciously agreed to oversee preparations for the come-out ball, she was compelled to reduce the situation to diminutives. Thus the come-out for Veronica and Alicia, costing the Lathams many hundreds of pounds, was a "little" party, and Alicia herself, though three inches taller than Lady Belcomb, a "countrified little thing."

"That reminds me; we must be certain Lord Hartleigh has been sent an invitation. It would be mortifying, after his thoughtful visit, to discover he had not been included."

Isabella, who had, purely on her cousins' account, resisted the temptation to hurl said invitation into the fire, assured her aunt that all was well. With the coming ball, Lady Belcomb's responsibilities would cease, according to the agreement. It would then be up to Isabella to accompany her cousins on their debutante rounds, for Mama was bound to be too tired, or too bored. Idly, Isabella wondered where she would fit in. Would she be required to sit with the rest of the gossiping duennas and attempt to converse with them? Did chaperones dance? The music had just begun, and Isabella looked down to see her white satin slippers tapping in time, as though they had nothing to do with respectable chaperones. Were chaperones allowed to tap their toes to the music? Smiling at the thought, she looked up to meet a pair of glittering topaz eyes gazing down at her.

"Lady Belcomb, Miss Latham, may I present Mr. Basil Trevelyan," Lord Tuttlehope announced, with the air of one introducing Prinny himself. And she should count herself lucky, Freddie thought. Mousy old thing for Basil to be leg-shackled to, poor chap, with all his romantic poetical nonsense.

But Mr. Trevelyan was looking at the possible answer to his prayers. Hadn't Aunt Clem warned him that few parents would care to put their daughters' fortunes in his hands?

"Even I should not," she warned him, "though I do believe you'll outgrow it in time."