Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: NYLA

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

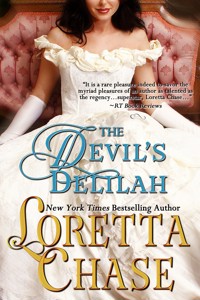

The classic traditional Regency from /New York Times bestselling author, Loretta Chase, is back… "One of the finest and most delightful writers in romance." –Mary Jo Putney What's a girl to do, when her father, known as Devil Desmond, is one of the most infamous rogues in all of England? Delilah Desmond is not happy. To provide for her, her father has sold his memoirs, filled with scandalous and embarrassing exploits—effectively ruining her chances for a suitable marriage, so she can support her family while saving her father from disgrace. But it seems the manuscript is in demand by all sorts of unscrupulous persons, and preventing its publication is going to be impossible; especially now that it has been stolen. Can the hot-tempered Delilah and her very unwilling accomplice, absent-minded, bookish, Jack Langdon with his soft grey eyes and tousled hair, salvage the disaster? It appears that deceptively quiet Jack may have a core of steel—and be the one man smart and strong enough to be the hero she'd been hoping for all along.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 397

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1990

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Devil’s Delilah

Loretta Chase

Copyright

This ebook is licensed to you for your personal enjoyment only.

This ebook may not be sold, shared, or given away.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the writer’s imagination or are used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

The Devil’s Delilah

Copyright © 1990 by Loretta Chekani

Ebook ISBN: 9781617508530

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this work may be used, reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

NYLA Publishing

350 7th Avenue, Suite 2003, NY 10001, New York.

http://www.nyliterary.com

Chapter One

Rain drummed furiouslyagainst the sturdy timbers of the Black Cat Inn. Within, its public dining parlour, tap room, and coffee rooms overflowed with orphans of the storm. From time to time a flash of lightning set the rooms ablaze with glaring light, and the more timid of the company shrank in terror at the deafening cannonade of thunder which instantly followed.

“Filthy night, sir,” said Mrs. Tabithy, approaching one of her guests. “There’ll be a sight more of them”—she nodded toward the group crowding the main passageway—” unless I miss my guess. If you’d come but a quarter hour later I couldn’t have given you a private parlour, not if my life depended on it.”

“Very kind of you, I’m sure,” said the guest, gazing absently about the room.

His hostess eyed the thick volume in his hands and smiled. His mien was that of a gentleman. The quality and cut of his attire, despite its untidiness, bespoke wealth. He was a good-looking young man—not yet thirty, she would guess—and, judging by both the book and the rather dazed expression of his grey eyes, one of those harmless scholar types. This fellow would offer no trouble at all.

“Just down that passage,” she said aloud. “Third door on the left. I’ll send Sairey along to you as soon as ever I can—but she has her hands full, as you can see.”

The young man only gave a vague nod and wandered off in the direction she indicated.

His hostess had guessed aright. Mr. Jack Langdon was a quiet, bookish sort, too preoccupied with his own musings to take any note of the service accorded him. At present he was more preoccupied—or muddled, rather—than usual. This was because Mr. Langdon was recently disappointed in love.

Retiring by nature, he was now sorely tempted to betake himself to a monastery. Unfortunately, he had responsibilities. Therefore he was taking himself to the next best refuge, his Uncle Albert’s peaceful estate in Yorkshire. His uncle, Viscount Rossing, was a recluse, even more book-minded than the nephew. Jack could spend the entire summer at Rossing Hall without once having to attempt a conversation. Better still, except for servants, he need never see a single female.

Sadly contemplating the particular female who had cast a blighting frost upon his budding hopes, Mr. Langdon lost count of doors and opened the fifth.

The room was exceedingly dim, which was annoying. He could not read comfortably by lightning bolts, frequent as they were. He’d scarcely formulated the thought when the lightning crackled again to reveal, lit like a scene upon the stage, a young woman pressing a pistol against the Earl of Streetham’s breast.

Without pausing to reflect further, Mr. Langdon hurled himself at the young woman, knocking her to the floor and the earl against the wall. Lord Streetham’s head cracked against the window frame and his lordship slid, unconscious, to the floor.

The young woman remained fully conscious though, and in full possession of the pistol. As Jack grabbed for it, she jammed an elbow into his chest and tried to shove him away. He thrust the elbow away, and went again for the weapon. Her free hand tore into his scalp. He tried to pull away, but she caught hold of his ear and yanked so hard that the pain made his eyes water. While he struggled to pry her fingers loose, she brought up the hand wielding the weapon behind his neck. Just as the pistol’s butt was about to slam down on his skull, Jack seized her wrist. He squeezed hard and the weapon dropped to the floor a few inches from her head. He lunged for the pistol, but her nails ripped into his scalp once more, jerking him back.

Mr. Langdon was growing distraught. To have assaulted a woman in the first place was contrary to his nature. Now he seemed to have no choice but to render her unconscious. He knew he could, having been well-trained at Gentleman Jack’s, yet the idea of driving his fist into a feminine jaw was appalling.

While he struggled with his sense of propriety, she struggled to better purpose, punctuating her blows with a stream of choked oaths that would have shocked Mr. Langdon to the core had he been able to pay full attention. He, however, had all he could do to keep her down. He prayed she’d tire soon and spare him the shame of having to beat her senseless. But she only writhed, elbowed, scratched, and pummelled with unabated ferocity.

Mr. Langdon’s prodigious patience began to fail him. In desperation, he grabbed both her wrists and pinned them to the floor. She cursed vehemently now, but her heaving bosom showed she was finally weakening, though she continued twisting frantically beneath him. That is when his concentration began to fail.

The form beneath his was strong and lithe, and he became acutely aware of supple muscles and lush curves. As her writhings abated, a warmth more beckoning than the heat of combat began to steal over him. In a moment it had stolen into his brain, along with a host of other inappropriate sensations, all of which loudly demanded attention.

Mr. Langdon attended and—alarmed at what he found—hastily lifted his weight off her. His adversary promptly thrust her knee against a portion of his anatomy.

Jack gasped and rolled onto the floor, and the young woman scrambled to her feet, grabbed her pistol, and dashed out of the room.

Moments later, as Jack was struggling to rise, he heard a low groan and saw the earl painfully raising his head from the floor. Jack crawled towards him. Blood trickled past Lord Streetham’s ear along his jaw line.

“My Lord, you’re hurt,” said Jack. He fumbled in his coat for his handkerchief.

Lord Streetham pulled himself up to a sitting position, clutching his head. “Damned madwoman,” he muttered. “How was I to know she wasn’t—what are you doing?” he cried.

“Your head, My Lord-”

“Never mind that. Go find the she-devil. I’ll teach her to—well, what are you waiting for?”

From his earliest childhood Jack Langdon had run tame in the earl’s house, dealt with on the same terms as his lordship’s son, Tony. Jack had played with Tony, studied with Tony and – periodically – been flogged with Tony. When, therefore, Tony’s father told Jack to do a thing, Jack did it.

He stumbled to his feet and out of the room.

“Well, Delilah, and now what have you been up to?” said Mr. Desmond as he coolly studied his daughter’s disheveled appearance.

Delilah glanced at the pudgy little man who stood, perspiring profusely, beside her papa. “Oh, nothing,” she said, airily indifferent to the scene of carnage she’d recently left. “A misunderstanding with one of our fellow guests. Two, actually,” she added, half to herself.

“Good heavens, Miss Desmond, it appears to have been a great deal more than that. I hope one of the gentlemen has not behaved uncivilly. A terrible thing, these public inns,” said the damp fellow. “You really should not have come unattended. Your maid –”

“My maid has a sick headache, Mr. Atkins, though I have told her repeatedly that only women of the upper classes are permitted the luxury of migraines. I fear she has aspirations above her station.” Miss Desmond impatiently thrust her tangled black curls back from her face.

“Mr. Atkins is right, my love. You should not have come.”

“Of course I should, Papa. The matter nearly concerns me—as I hope you’ve explained to Mr. Atkins.” She turned to the small man. “I believe Papa has already informed you of his change of plans. Therefore I cannot think why you have travelled all this way on a fruitless errand.”

“Oh, Miss Desmond, not fruitless, surely. As I was just explaining to your father—” Mr. Atkins stopped short because at that moment the door flew open.

The woman Jack sought stood with her back to the door, but as he drew on his remaining strength for a second assault, he heard a low, lazy voice say, “Ah, the guest in question, I believe.”

Mr. Langdon stopped mid-lunge as his gazeswung towards the voice. There were others in the room. Two others.

One was a small, rather plump, exceedingly agitated creature with a moist, round face. At the moment he was nervously mopping his forehead with his handkerchief.

The other—the voice’s owner—was a tall, powerfully built man with a darkly handsome face and riveting green eyes. He stood coolly, almost negligently, surveying the intruder, yet his very negligence was threatening.

It occurred to Mr. Langdon that when and if the Old Harry took human form, this was the form he must take. The man exuded force, danger, and something else Jack couldn’t define.

“I beg your pardon for interrupting,” said Jack, bracing himself for he knew not what, “but I’ve been sent to apprehend this woman.”

“You apprehended me once already,” said she. “This smacks of obstinacy.”

“Ah, it is the guest,” said the satanic-looking fellow. He took a step towards Jack and smiled. The gleam of his white teeth was not comforting. “My dear young man, you must give up your pursuit of my daughter. She objects to being pursued by gentlemen to whom she has not been introduced. Objects most strongly. She is likely to shoot you.”

“I don’t doubt it,” said Jack. “She just tried to murder the Earl of Streetham.”

“Dear heaven!” cried the small man. “Lord Streetham? Oh, Miss Desmond, this will never do!”

“No, it will not,” the man who claimed to be her father agreed. “How many times have I told you, Delilah, not to murder earls? Really, my dear, it is a very bad habit. Steel yourself. Overcome it. Mr. Atkins is quite right. Won’t do at all.” He turned to Jack. “My dear chap, I’m terribly sorry, but this is a fiend we never have done wrestling with. Rest assured that I will speak very firmly to my daughter later. Pray don’t trouble yourself further about it. Goodbye.”

Though this response was hardly satisfactory, there was something so assured in the man’s tones that for one eerie instant, Jack, half convinced he was acting in a comic play, very nearly took his cue. He had even begun to back out of the room when he felt the young woman’s gaze upon him. He turned towards her and froze.

In the heat of battle he had become conscious of her lush person. Now he saw that her heavy black hair framed a perfect oval face startlingly white in contrast, smooth and clear as his mother’s precious porcelain. Her eyes, the grey-green of a stormy sea, had a slight upward slant. As she watched his baffled face, her generous mouth curved slightly in an enigmatic, maddening smile that made his heart lurch within him. Jack suddenly needed air.

All the same, he could not retreat. This young Circe had attempted the worst of crimes.

“I’m very sorry, sir, but I’m obliged to be troubled,” said Jack, attempting similar nonchalance. “I’m afraid this is a matter for the constable.”

“Dear God!” Mr. Atkins sank into a chair.

“As you like,” said Miss Desmond. “I wish to speak to a constable myself. Perhaps he can explain why your Lord Streetham is permitted to wander about public inns assaulting defenceless young women. He cannot be very successful at it, since he requires accomplices. I shall recommend he find a hobby better suited to his limited skills.”

“Assaulted you! You were holding a pistol to his heart.”

“Ah, now I understand. His lordship is a tall man?” Mr. Desmond enquired.

“Yes, but that –”

“There you have it. She could not hold the pistol to his head. Much too awkward. As you can see, Delilah is scarcely above middle height.”

“This is hardly a time for humour,” said Jack, much provoked. “Lord Streetham lies bleeding just a few doors away.”

“There you are mistaken,” said Delilah’s father. “He is bleeding slightly, but he is standing right behind you.”

Jack whipped around. Sure enough, there was his lordship, leaning weakly against the door frame and pressing a handkerchief to the side of his head.

Mr. Atkins scurried towards the earl. “My Lord, you are hurt. Here, take my handkerchief. Shall I send for a physician? Shall I send for water? Shall I send for brandy?” The man continued babbling as he alternately thrust his handkerchief in the earl’s face and mopped his own moist brow.

“Who is this person?” the earl demanded. “Why does he wave that filthy rag in my face?” He nodded to Jack. “Remove him, Jack. This is a private matter.”

‘Mr. Atkins did not wait for removal. He shot past the earl out of the room.

Lord Streetham’s icy glare now fell upon the dark gentleman, who produced another gleaming grin. The earl’s hauteur faltered slightly. “So it is you, Desmond,” he said. “When I heard that voice I was certain I’d passed over. Where else but in Hades would one expect to see you again?”

“But not, surely, where you’d expect to find yourself, eh, Marcus?” Mr. Desmond returned. “You are, I promise, still in this sad world, and this poor hostelry is hardly the Other Place, though the Devil himself takes refuge here from the storm.”

Lord Streetham manufactured a taut smile. “Then I may take it this young woman belongs to you?”

The green eyes glittered. “Young lady, if you please. This is my daughter, Delilah.”

“Daughter?” the earl repeated weakly.

The tension in the air was palpable. Once more Jack braced himself.

To his amazement, the earl’s hauteur vanished completely, replaced by a rather white expression of solicitude. “My dear young lady, a thousand apologies,” he said. “The poor light—and my eyes are not what they used to be. I took you for that saucy maid. A terrible misunderstanding.”

Miss Desmond stared coldly at him.

“Nearly fatal, actually,” said her father. “Now I suppose I must call you out. How tiresome.”

“Too tiresome, Papa,” said Miss Desmond. “His lordship has apologised. I am unharmed.” Obviously, his lordship was not, but the young lady tactfully forbore to mention this. “Now if his accomplice will apologise as well,” she added with an amused glance at Jack, “we might all continue peaceably about our business.”

Jack was certain that some sort of signal passed then from daughter to father, but he could not perceive what it was. A flicker of an eyelid... an infinitesimal movement ... or even—impossible—no one could read another’s mind.

He looked to the earl for guidance.

“A misunderstanding, Jack,” said Lord Streetham. “That’s all.”

All. He, Jack Langdon, had violently assaulted an innocent young woman who had only been attempting to defend her honour. He wished the floor would open up and swallow him, but as floors are rarely accommodating in this way, he reddened with mortification instead.

“I—I do beg your pardon, Miss Desmond,” he stammered. “I’m dreadfully sorry—and—and—” Abruptly he recalled the appalling urges she’d aroused. “I hope I caused you no injury.”

“Oh, no,” she answered soberly, though her eyes were lit with amusement. “And I trust I caused you none.”

Mr. Langdon’s colour deepened. “N—no. Of course not.”

“Very well, Mr.—?”

“Langdon,” the earl impatiently supplied. “Jack Langdon. Known him since he was a babe. Wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

“Very well, Mr. Langdon. Apology accepted.”

Mr. Langdon begged pardon of the room at large, then fled.

He found the correct parlour this time and sat staring at the table for half an hour before he remembered that he’d dropped his book during his scuffle with Miss Desmond. Reluctant to risk bumping into any of the witnesses to his humiliation, he sent a servant to retrieve the volume.

Once it was safely in his hands, Jack relaxed somewhat, and even managed to order his dinner without stammering. This was about all he could manage. He ate his meal without tasting it, and read his book without comprehending a syllable. The storm continued with savage fury, and he noticed nothing. Hours later, when all was quiet within and without, he crept to his room and stared at the ceiling until daybreak.

While Mr. Langdon was trying in vain to find oblivion in his book, and Miss Desmond was recounting her adventure to her papa, Lord Streetham was relieving his own frustrations at the expense of the hapless Mr. Atkins. After berating the poor fellow unmercifully for nearly revealing their connexion, his lordship proceeded to an unkind analysis of said connexion.

The world knew Lord Streetham as an enthusiastic book collector. Mr. Atkins knew him as a secret partner in his publishing business. That this was a closely guarded secret was perhaps because of the firm’s tendency to offer the British public some of the naughtiest volumes ever to be hidden under mattresses or tucked away in locked drawers. Despite readers’ regrettable affinity for anatomy manuals, directories of prostitutes, reviews of crim con cases, and guides to seduction, the business had not done well of late—as the earl was at present pointing out.

Atkins was obviously a failure, his lordship observed, perhaps a fraud as well. Be that as it may, he now had leave to plunge into bankruptcy solo. In short, Lord Streetham proposed to cease tossing good money after bad.

“But, My Lord, to give up now—when a brilliant success is practically in my grasp—virtually in the printer’s hands.” Mr. Atkins squeezed his eyes shut and bit his lip. “Oh, my. I had not meant—oh, dear me.”

Lord Streetham paused in the act of bringing his glass to his lips and studied his companion’s face over the rim. Then he put the glass down and fixed his pale blue eyes on the publisher.

“What hadn’t you meant?” he asked.

The man only stood speechless and terrified, gazing back.

“You’d better speak up, Atkins. My patience is quite at an end.”

“My—My Lord, I c—cannot. I’m sworn to s—secrecy.”

“You have no business secrets from me. Speak up at once.”

The publisher swallowed. “The memoirs, My Lord.”

“I am not in the mood to catechize you, Atkins, and you are provoking me.”

“Hismemoirs,” the publisher said miserably. “Mr. Desmond has written his memoirs and I have paid him—partially, I mean, as an incentive to complete them speedily. That is why I am here. I learned he was travelling to Rossingley to visit relatives, so I came up from Town to—to spare him the trouble of bringing them to me.”

“Written his memoirs, has he?” Lord Streetham asked as he absently poured more wine into his still nearly full glass.

“Yes, My Lord. I saw them—at least part of them—myself. He had written to ask whether I had any interest, and naturally, being familiar with his reputation—as who is not?—I made all haste to examine the work. I had to travel all the way to Scotland, but the journey was well worth my while, I assure you. All of Society will be clamouring to read Devil Desmond’s story. We’ll issue it in installments, you see, and—”

“And have you got them?” his lordship asked.

Mr. Atkins was forced to admit he had not, because Mr. Desmond had raised difficulties.

“Of course he has,” said the earl. “If you know his reputation, you should know better than to give Devil Desmond money before you have the goods in your hands. You are a fool. These memoirs do not exist. He showed you a few scraps of paper he’d got up for the purpose, and you were cozened.”

The publisher protested that the manuscript must exist, or Miss Desmond would not have been so eager to interrupt the meeting with her father. “He’s ready to publish,” Atkins explained, “but she won’t let him. She’s afraid of the scandal. The girl’s looking for a husband, you know. That’s why Mr. Desmond has returned to England.”

The earl sneered. “Devil Desmond’s daughter? A husband? The wench must be addled in her wits. I suppose she means to find herself a lord—a duke, perhaps?” Lord Streetham chuckled. “Silly chit. What’s one more scandal to her? As it is—but no, ancient history bores me. Still, the public dotes on such sorry tales, and you are correct. These memoirs, if they truly exist, are certain to be popular. Unfortunately...” He paused and lightly drummed his fingers on the table.

“My Lord?”

“People change, Atkins,” said the earl, without looking up. “Some of those with whom Desmond consorted in his wicked youth have died of their excesses. Those who survived are today men of prominence, highly respected. They will not take kindly to such an exposure of their youthful follies. If you are not careful, you will be sued for libel.”

“My Lord, I assure you—”

Lord Streetham continued, unheeding, “Furthermore, libellous or not, there may be information that would destroy the peace of innocent families. We can’t have that.” His lordship sipped his wine with an air of piety.

Mr. Atkins panicked. “Oh, My Lord. For fear of a few domestic squabbles you are prepared to deprive the world of these recollections? I promise you, they’ll be pounding at the doors every time a new installment is announced. I beg of you, My Lord, reconsider.” Tears formed in the publisher’s eyes.

Lord Streetham reflected for several agonising minutes while Mr. Atkins mopped his brow and waited.

“Very well,” said the earl at last. “It would be wrong to deprive the public. He has lived an extraordinary life. You may publish, if you can—but on one condition.”

“Anything, My Lord.”

“I must approve the material first. A bit of editing here and there will do no harm, and may spare some of my colleagues considerable pain.”

Having agreed to accept any condition, Mr. Atkins could hardly quarrel with this modest request. Some time later, however, as he took himself to bed, he bewailed the cruel fate that had brought Lord Streetham to this accursed inn. By the time his lordship had done “approving” Devil Desmond’s memoirs, they’d look like a book of sermons, and Mr. Atkins would consider himself very fortunate if even the Methodists would buy them.

Lord Streetham took to his own bed in bad humour. He might have known this would be a night of ill omen from the start, when his mistress had failed to appear. Then, when Desmond’s chit had entered his private parlour, he’d mistaken her for the tart, and nearly had his claret spilled. After that, he’d narrowly escaped certain death at Devil Desmond’s hands, had had to truckle to the monster—with Jack Langdon, the soul of rectitude, a witness to the whole tawdry scene. Worst of all were these curst memoirs, whose pages must surely reveal secrets of his own to the unsympathetic London mob.

His lordship was not altogether easy in his mind about the publisher, either. The choice between certain success and certain ruin is not a difficult one, and a desperate man is not a patient one. Suppose Atkins betrayed him, and made off with the manuscript? Suppose, even if he didn’t, the book was so scurrilous that editing would not be enough? Perhaps it were safest to destroy the work altogether. With these and hosts of other, equally unsettling questions did Lord Streetham while away the long, dreary night.

Chapter Two

Hoping once again to avoid his fellow travellers, Jack stole out of his room shortly after dawn. As he was about to turn the corner towards the stairs, there came a noise from a room nearby. Jack glanced back at the precise instant that another gentleman came hurrying around the corner. The two collided, and Mr. Langdon was sent staggering against the wall.

“Drat—so sorr—Jack!” exclaimed the gentleman. “Is that you, truly?”

He reached out a hand to help, but Jack had swiftly recovered his balance, though he was still rather dazed. He glanced up into what most women would have described as the face of an angel. It was a face that might have been painted by Botticelli, so classically beautiful were its proportions, so finely chiseled every feature, so clear, blue, and innocent its eyes, so golden the halo of curls that crowned it.

This, however, was not only the face of a mortal man, but of a most unseraphic member of that gender. Lord Streetham’s son, the Viscount Berne, was well on his way to becoming the most dangerous libertine the British peerage had ever produced. He was also Jack’s oldest friend.

“Yes, it’s me—at least I think so,” said Jack with a grimace as he rubbed the back of his head.

“What brings you here—up and about at this ungodly hour? And as usual, never looking where you went. Why, I nearly threw you down in my haste.”

“That’s quite all right, Tony,” said Mr. Langdon. “I’m growing accustomed to falling on my face.”

Lord Berne’s innocent countenance immediately became pitying. “Oh, yes, I heard about that. Too bad about Miss Pelliston.”

Mr. Langdon winced. He had not been aware that his failure was common gossip.

“Still, that’s the way of love,” the viscount consoled. “Plants you a facer every now and then. The secret is to pick yourself up and march on to the next battle. We civilians must take our lesson from Wellington.”

He threw an arm about his friend’s shoulder and led him down the stairs. “First, you want sustenance. We shall breakfast together. Then, you must return with me to the ancestral pile for a long visit. I’m forced to ruralise because I am obliged to court Lady Jane Gathers. Of course she’ll make a paragon of a wife. My sire’s judgement is infallible, as he incessantly reminds me.”

Since Lord Berne had a tendency to run on wherever his fancy took him, his monologues could continue for hours if not ruthlessly interrupted and hauled back to the point.

Accordingly, Jack cut in. “You don’t usually ruralise at inns—at least not so close to home. What brings you here?”

“A wench of course. What else? Perhaps you have not yet met the fair and saucy Sarah? No matter. I scarcely saw her either, for I’d no sooner stepped into the coffee room than I spied a high flyer sitting lonely and neglected amid the storm-tossed rabble.

“What choice had I but to come to the dark-haired damsel’s aid?”

“Lady Jane will hardly appreciate that sort of knight errantry,” said Jack as they stepped into the main passage.

“Lady Jane is determined to know nothing about such matters, which is most becoming in her. I only wish her face were more becoming. But no matter. We’ll woo her together, you and I,” Tony offered.

He deftly steered his preoccupied friend into the public dining room. “Perhaps you’ll steal her away. Actually, Jack, I wish you would. She’s all very well, but I’m not ready—Good God! Where did she come from? With my noble sire, no less. Where in blazes did he come from?”

Mr. Langdon followed his companion’s gaze past the enormous communal table to a quiet corner near the fireplace. There Mr. Desmond and his daughter sat breakfasting with the Earl of Streetham.

Though the last thing in this world Jack wanted was interaction with any of the three, he could hardly expect Tony to ignore his own father, particularly when that parent was in the company of a beautiful young woman. There was no escape, because Tony had a firm grip on his friend’s arm and was propelling him towards the table.

Jack employed the next few minutes examining with apparent fascination a small landscape containing several evil-looking sheep which hung upon the wall some inches above Miss Desmond’s head. Dimly he heard introductions and a number of what he was certain were falsehoods as the earl and his son respectively accounted for their appearance at the Black Cat.

Mr. Langdon nudged himself to proper attention when he heard the earl renew his pleas that the Desmonds be his guests at Streetham Close. Since his lordship addressed his requests primarily to thedaughter, Jack gathered that she was the more reluctant of the pair. In the next moment, however, Tony added his persuasions, and, as might be expected, Miss Desmond capitulated.

Having completed their meal, the trio soon left, one of them followed by a look of such languishing adoration from Lord Berne that the waiter knocked over two chairs in his haste to reach the table, so certain was he the young gentleman was about to perish of hunger.

Mr. Langdon, being inured to his companion’s fits of romantic stupefaction, took no notice. Their breakfast was speedily served, and while they ate, Jack calmly explained why he could not visit Streetham Close. His uncle was expecting him, he said. He was not in a humour to be sociable. He had not read a book through in months. These and other lame excuses received short shrift from the Viscount Berne.

“You only want to go off to hide and feel sorry for yourself, Jack, and that’s unhealthy. To wish to be elsewhere when this exotic flower will be under my roof is evidence of mental decay. We must make you well again. If those grey eyes of hers don’t restore you to manhood, I don’t know what will.”

“They’re green,” said Jack.

“Grey.”

“Green. And I don’t need to be restored by anyone’s eyes. I want peace and quiet, Tony, and I must tell you there’s nothing peaceful about the pair of them.” Jack was on the brink of revealing the previous night’s adventure when his friend blithely cut in.

“I don’t expect them to be peaceful,” said Lord Berne. “Don’t you know who that is? Devil Desmond, the most infamous rogue in Christendom. Adventurer, charlatan, and—at least until he wed— corrupter of feminine virtue the like of which has not been seen since Casanova. His conquests would populate—”

“Thank you, Tony. The broad outlines will do.”

“He’s a legend in his own time, I tell you. Never thought he’d return to England after that duel with Billings—but that’s aeons ago, isn’t it?”

Mr. Langdon scowled at his coffee. “Then I wonder at your father’s taking him under the ancestral roof.”

“His lordship grows pious in his dotage. Maybe he means to reform the Devil. Still, what do I care about the reasons? Delilah.” Lord Berne sighed. “Even her name throbs with sinful promise. She has not touched a hair of my head, yet I feel the strength ebbing from my very sinews.”

His friend sighed inwardly. Tony fell in love on a daily—sometime hourly—basis, and the results, in the view of some, amounted to a national tragedy. The pitiful remains of the feminine hearts Lord Berne had shattered lay strewn in a broad path from London to Carlisle. One more scrap of wreckage would not change the course of history—though, unless Jack much missed his guess, Miss Desmond’s heart was made of sturdier material.

For the philosopher, their interchange would provide an interesting study, but Mr. Langdon was not in a philosophic mood. He stubbornly insisted on going to his uncle’s.

Lord Berne played his trump card. “You must come, Jack, to save me from myself.”

“Rescue is not in my style,” was the irritated reply.

“But who else can keep me from straying beyond light dalliance into dangerous depths? Very dangerous, I promise you. You will not want to see the Devil put a bullet through my too tender heart, will you?”

“Then keep your hands to yourself.”

“But Jack.” Lord Berne fixed his friend with a wide-eyed gaze. “You know I can’t.”

Mr. Desmond and his daughter travelled in their own carriage, the earl preceding them on horseback. After they had driven some time in silence, Mr. Desmond remarked, “That young man interests me.”

“Which young man, Papa?”

‘My dear, you can hardly think I find that fair-haired coxcomb interesting. I have met his type across the world, through several generations. I refer to the Guest in Question. The unhappy young man with the rumpled brown hair and poetic grey eyes.”

“I did not find him poetic.”

“You most certainly did. Also, you felt sorry for him. I nearly swooned with astonishment.”

Miss Desmond gazed stonily ahead. “I did neither. Your eyesight is failing you, Papa, just like poor Lord Streetham’s.”

“You are very cross today, Delilah. Is it because the poetic young man turns out to be heir presumptive to Viscount Rossing and you regret your decision?”

Miss Desmond’s head snapped towards her father so abruptly that her gypsy bonnet tipped over her ear. As she straightened it she said angrily, “I am not going to force a man to marry me on some trumped up pretext of being compromised. It’s absurd.”

“He would have done it, though.”

“Because he’s an innocent babe. Oh, Papa, that’s not how I wish to begin—yet there’s no fresh beginning, is there? My feet scarcely touch English soil before I become embroiled in a dreadful scene. I wish I could act like a lady. I can act everything else, it seems,” she added ruefully.

“Had you acted a helpless female—which I take is your definition of a lady—you would have been dishonoured by that sanctimonious old hypocrite.”

“If I’d waited for my maid or kept to my room I should not have invited incivility.”

Mr. Desmond smiled, a far gentler smile than the one Mr. Langdon had observed the previous evening. “You were concerned that Mr. Atkins’s pleas would soften my susceptible heart. A natural anxiety, my dear, though quite unnecessary. In fact, I’ve given the matter a great deal of thought. Perhaps I should destroy those paltry literary efforts of mine, so we might proceed in this enterprise with easy minds. I made a great mistake in contacting Atkins, I know. But I wanted to ascertain the value of the work. Suppose I died suddenly?”

Delilah shuddered. “Don’t say such things, Papa.”

“It might have easily happened but a year ago. You and your mama would be left destitute, with no prospects of aid from either of our callous families. Insurance, I thought. A nest egg in case of calamity. Naturally I had to make sure the egg was a golden one.”

“Of course you did. And not another word about destroying your wonderful story, after all your months of work. As you say, calamities happen. I may never find a husband.”

“Or you may fall in love with a penniless young man.” .

Miss Desmond sniffed disdainfully. “I have no intention of falling in love with anybody. One cannot preserve a clear head and be in love at the same time. My marriage wants a clear head.”

“You mean a cold, calculating one, I suppose.” The parent sighed. “I fear your mama and I went sadly astray in your upbringing. We have failed you.”

“Oh, Papa.” Miss Desmond hugged her father, setting her bonnet askew again. “You have never failed me. I only hope I might be clear-headed enough to find a man half as splendid as you.”

“That, my love, wants a muddled head. What a silly girl you are. But at least you have recovered your temper. I shall endure the silliness.”

Whatever objections Lady Streetham had about entertaining the notorious Devil Desmond were ruthlessly crushed by her lord and master.

“I have reasons,” said he, “of a highly confidential anti political nature. You may treat him with civility or you may blight my Cabinet prospects. The choice is yours.”

After subduing his wife, Lord Streetham called upon his most trusted servants and, again citing national security, ordered them to search the Desmonds’ belongings.

While Lord Streetham and his minions laboured on behalf of the imperiled kingdom, Lord Berne took his guests on a riding circuit of the park. Mr. Langdon went as well, though he knew every stick, stone, and rabbit hole of every acre. He had his book with him, however, and whenever the group had occasion to pause, would take it out to stare blindly at the pages.

Miss Desmond found this behaviour most curious. As they were returning to the house, she asked Lord Berne, “Does he always have a book with him?”

“Always,” said her companion, glancing back at his friend, “even in Town, at the most magnificent balls, routs, musicales. There you’ll unfailingly find Jack Langdon with a book, which he unfailingly loses at some point, and must of course go poking about for. Drives the ladies wild. Not that I blame them. It must be most exasperating when you’re just commencing a bit of flirtation to see his eyes glaze over and then watch him wander off, talking to himself.” His own appreciative gaze dropped from her eyes to her lips. “Though I cannot understand his behaviour in the present case.”

“I find it perfectly understandable,” Miss Desmond answered lightly. “What lady can compete with Plutarch?”

The viscount opened his mouth to answer, but she added quickly, “Pray, My Lord, do not say it is myself, when the facts contradict you. Besides, that is too easy a compliment. You cannot think I was angling for it.”

“You need never angle for praise, Miss Desmond,” was the prompt reply.

The exotic countenance grew blank with boredom, and Lord Berne was wise enough to revise his tactics.

“Actually,” he said, dropping his voice, “Jack is more than usually abstracted because”—he paused dramatically—”he has had a disappointment.”

Miss Desmond was intrigued. “Really? What sort? It cannot have been love, since you say he eludes feminine wiles. What can it be?”

“To disclose that would be dishonourable.”

“Then you were dishonourable to mention it at all,” she retorted, tossing her head. This tipped her beaver riding hat over her forehead, causing several black tendrils to escape from behind. She impatiently thrust these back Tinder the hat while Lord Berne watched with every evidence of enchantment.

“As long as I am sunk beneath reproach, I suppose one more indiscretion can scarcely matter,” he said, when hat and hair had been jammed into order. “Yes, there was a lady in the case. Amazing, isn’t it?”

“She must have been extraordinary to distract him from his books.”

“Not at all. From what I’ve heard, she was a mousy little model of propriety—and a blue stocking. I think he’s had a narrow escape, though it wouldn’t do to tell him so, of course. A friend is obliged to sympathise and console.”

“Then I keep you from your obligations, My Lord. You must attend to Mr. Langdon, and leave Papa and me to make shift without you.” So saying, she rode ahead to catch up with her father.

“Bored so soon?” asked Mr. Desmond^. “I told you he was like everyone else.”

“On the contrary, he’s a wonderful gossip. In less than an hour I have learned the entire past Season’s on-dits.”

“Then doubtless the conversation grew too warm for your maidenly ears.”

Delilah shot him a disbelieving glance. “His lordship was courteously amusing, no more. Still, if the prey is not elusive, the hunter soon loses his relish for the pursuit, as you have told me a thousand times.”

The father grinned. “I am always right, of course. You’ve set your mind on Streetham’s heir, then?”

Delilah shook her head. “His parents would never condone it. I was most surprised by his lordship’s invitation. I don’t think he likes you, Papa.”

“Loathes me,” the Devil replied easily. “Still, he wouldn’t want his faux pas to be noised about—and even I am not so low a cur as to tattle on my gracious host, am I?”

“What an old hypocrite he is! Naturally his son is out of the question.” She smiled into the sunlit distance. “As a husband, I mean. But as a pursuer, he could prove useful. It would be pleasant to have at least one suitor on hand when the Little Season begins. Let us hope he pursues me as far as London.”

It was fortunate that Lord Streetham was not a superstitious man, else he had concluded a cursehad fallen upon him from the moment he’d strayed past the Black Cat’s portals. A diligent search of all of the Desmonds’ belongings, including their carriage, had yielded nothing.

Lord Streetham now had two choices. He could offer Desmond an enormous sum for the memoirs. Though the earl was tight-fisted, he was prepared to pay in so urgent a case. The trouble was, he must pay Desmond, and to admit himself at that creature’s mercy was unthinkable. The second choice— to seek his irresponsible son’s help—was nearly as unthinkable. Yet this was one of the few enterprises in which Tony’s narrow talents could be useful. Thus, as soon as the group had returned to the house, Lord Streetham sent for his son.

“I suppose you are on your way to making a conquest of Miss Desmond,” said the earl, once the door was closed.

Tony shifted uneasily. “I was only trying to entertain them, sir. That is one’s duty to one’s guests.”

“I’ll tell you your duty,” the earl snapped. “I didn’t ask them here for their amusement or yours, and I mean to be rid of them as soon as possible. Your mother is still in fits, and she doesn’t know the half of it.” Lord Streetham proceeded to tell his son the whole of it—or most of it, for he did not reveal precisely what revelations he feared. He dwelt instead upon the ignorance of the public and the jealousy of political rivals. The latter, he insisted, would snatch at any straw that might discredit him.

“They will twist minor peccadillos out of all recognition and make me appear unfit to lead,” he stiffly explained. “What you or I, as men of the world, would shrug off as youthful folly they will exaggerate into weakness of character. Mere boyish pranks will be transformed into heinous

crimes.”

He turned from the window in time to catch his son grinning. The grin was hastily suppressed.

“I’m delighted you find this so amusing,” said Lord Streetham coldly. “Doubtless your mother will find it equally so, particularly when she grows reluctant to go about in public, for fear of hearing her former friends snickering behind their fans, or—and I’m sure this will be most humorous—enduring their expressions of pity.”

Lord Berne became properly solemn. “I beg your pardon, My Lord. I did not mean—”

“I’ll tell you what you mean, you rattle! You mean to relieve Desmond of that confounded manuscript.”

“I?”

“The girl, you idiot. If you must dally with her, then do so with a purpose. I am unable to locate the memoirs. That does not surprise me. Desmond is cunning. She may be equally so—certainly her mother is—but she is a female, and all females can be managed.”

Since Lord Berne had never met a young woman he couldn’t manage, he could hardly find fault with this reasoning. Nor, being sufficiently intelligent, was he slow to grasp what his father wished him to do.

“You believe I might persuade her to turn this manuscript over to me, sir?” he asked.

Lord Streetham uttered a sigh of vexation. “Why else would I impose so on that depraved brain of yours? Of course that is what I wish. Now go away and do it,” he ordered.

Lord Berne went away not altogether pleased with his assignment—which was rather odd, considering this was the first time his father had ever trusted him with any matter of importance. Furthermore, what was at stake was power, and the viscount had selfish reasons for preferring that his father’s not be diminished in any way. Lord Streetham’s influence had more than once saved his son from an undesirable marriage, not to mention tiresome interviews with constables.

The trouble was, the son was accustomed to pursue pleasure for its own sake. Though he would have been delighted to dally with the ravishing Miss Desmond, doing so as a means to an end was very like work, and his aristocratic soul shuddered at the prospect.

Still, he thought, his noble sire could not possibly expect him to begin this minute. Consequently, Lord Berne took himself to the water tower for a cold bath, and remained there, coolly meditating, for two hours.

Chapter Three

Though she had bathed and dressed leisurely, Miss Desmond discovered she had still the remainder of the afternoon to get through and no idea what to do with herself.

Lady Streetham, Delilah knew, was not eager for her company, and the feeling was mutual. Papa was having a nap. Her host was closeted with his steward. Lord Berne, according to her maid, had not yet returned to the house.

Clearly, Miss Desmond would have to provide her own amusement until tea. The prospect was not appealing. She could not play billiards, because that was unladylike. She doubted very much her hosts would approve her gambling with the servants. For the same reason, she could not spend the time in target practice. This enforced inactivity left her to her reflections, which were not agreeable.

Though she’d made light of it to her father, last night’s contretemps preyed on her mind. It was no good telling herself, as her father had assured her, she hadn’t had any choice. She might have attempted at least to reason with the earl before drawing out her pistol. Certainly she needn’t have wrestled, for heaven’s sake, with Mr. Langdon. Shemight have pretended to faint or burst into tears, but not one of these alternatives had occurred to her, though they would have been instinctive to any truly genteel young lady.

Delilah Desmond had a great deal to learn about ladylike behaviour, that was for certain. She hoped Lady Potterby would be up to the task of reeducating her grand niece. Otherwise that grand niece would never attract the sort of gentleman she needed to marry.

Right now, for instance, she ought to make an effort to impress her stony hostess by conversing with her on some suitably dull subject, preferably while doing needlework. The trouble was, Delilah was heartily sick of Lady Streetham’s condescension and would be more likely to plunge her needle into that lady’s starched bosom.

Miss Desmond decided her wisest course was to take a stroll in the gardens. At least they were extensive enough to make the walk something like real exercise.