Jahrbuch · Year Book · Anuario 2016 - 2017 E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

The second Year Book of the Project "Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan" (https://mayadictionary.de) includes six research notes and two project reports released in 2016 and 2017. In addition to the electronic distribution format the project makes a selection of its digital resources periodically availableas an e-book and a printed volume. This web-to-print initiative is part of the project's long term preservation and information dissemination strategy, combining the traditional publication formats with digital distribution of research data.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 274

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

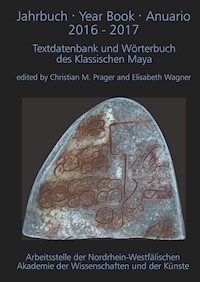

Cover:

Shell fragment of unknown provenance

PNK: EMB IV Ca 50468

5,4 x 6,3 x 2 cm, 600 - 900

Ethnologisches Museum der Staatlichen Museen, Berlin

3D-Model by TWKM, 2018 (courtesy of EMB)

Table of Contents

Foreword

PROJECT REPORTS 2014 - 2017

Milestone Report 2014 - 2016

Nikolai Grube, Christian Prager, Katja Diederichs, Sven Gronemeyer, Elisabeth Wagner, Maximilian Brodhun, and Franziska Diehr

Annual Report 2017

Nikolai Grube, Christian Prager, Katja Diederichs, Sven Gronemeyer, Antje Grothe, Céline Tamignaux, Elisabeth Wagner, Maximilian Brodhun, and Franziska Diehr

RESEARCH NOTES 2016 - 2017

The Logogram JALAM

Nikolai Grube

Filling the Grid? More Evidence for the <t’a> Syllabogram

Sven Gronemeyer

A Possible Logograph XAN “Palm” in Maya Writing

Christian Prager and Elisabeth Wagner

Two Captives from Uxul

Nikolai Grube and Octavio Quetzalcoatl Esparza Olguín

Historical Implications of the Early Classic Hieroglyphic Text CPN 3033 on the Sculptured Step of Structure 10L-11-Sub-12 at Copan

Christian Prager and Elisabeth Wagner

Jun Yop Ixiim – Another Appellative for the Ancient Maya Maize God

Elisabeth Wagner

Foreword

The hieroglyphic script of the ancient Maya, which has been only partially deciphered, is one of the most significant writing traditions of the ancient world. In 2014, the project Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan was established at the University of Bonn by the North Rhine-Westphalian Academy of Sciences, Humanities and the Arts and the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities, with the goal of researching the written language of the Maya. The project uses digital methods and technologies to compile the epigraphic contents and object histories of all known hieroglyphic texts. Based on these data, a dictionary of the Classic Mayan language will be compiled and published near the end of the project’s runtime in 2028. The project is methodologically situated in the Digital Humanities and is conducted in cooperation with the Göttingen State and University Library.

In addition to the electronic distribution format the project makes a selection of its digital resources periodically available as an e-book and a printed volume. This web-to-print initiative is part of the project’s long term preservation and information dissemination strategy, combining traditional publication formats with digital distribution of research data under the label of CC-BY. Principally, project information, in particular stable web contents and publications that are released over the course of the project, will be made available in digital format at no cost on the project’s website, which has its own ISSN 2366-5556. In addition, each contribution is permanently linked to a DOI, a handle to uniquely identify objects, standardized by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). DOIs remain fixed over the lifetime of the documents, whereas their location and metadata may change. The project’s website is also registered as a blog in the catalog of the German National Library and in the international ISSN Portal. This situation guarantees that blog contents will be citable as an internet publication with an open target audience.

The second Year Book of the project Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan includes online publications that members and associates of the research project have issued on the website mayawoerterbuch.de. The original texts have been revised and partly supplemented with new information. The volume includes two project reports and six epigraphic research reports published in 2016 and 2017. The first section contains two project reports: The Milestone Report 2014-2016 and the Annual Report 2017 by Nikolai Grube, Christian Prager, Katja Diederichs, Sven Gronemeyer, Elisabeth Wagner, Maximilian Brodhun, and Franziska Diehr. Both provide a detailed summary of all project activities and results from 2014 to 2017. The following section exhibits the printed version of six epigraphic research reports by project members and associated scholars. In his Research Note 3 entitled The Logogram JALAM Nikolai Grube offers a decipherment for a rare logograph listed as T284 in Thompson’s catalog of Maya hieroglyphs. The next paper Filling the Grid? More Evidence for the <t’a> Syllabogram by Sven Gronemeyer (Research Note 4) reviews David Stuart’s reading proposal for a t’a-syllabogram and enriches the evidence by providing more examples in different productive contexts. The third paper A Possible Logograph XAN “Palm” in Maya writing by Elisabeth Wagner and the volume editor (Research Note 5) explores the idea that Maya scribes used a logograph for the word “palm” in their writing system. The relevant graph renders the image of a palm, probably for the word xan “palm”. Nikolai Grube and Octavio Quetzalcoatl Esparza Olguín’s paper Two Captives from Uxul present two panels displaying captives from the Maya site of Uxul (Research Note 6). One panel originates from Coba, the second panel is preserved only fragmentary and its provenance is unknown. Research Note 7, titled Historical Implications of the Early Classic Maya Hieroglyphic Text CPN 3033 on the Sculptured Step of Structure 10L-11-Sub-12 at Copan, by Christian Prager and Elisabeth Wagner, examines an Early Classic hieroglyphic inscription on a step found at Copan. The authors’ examination has revealed that this text exhibits a dynastic sequence with the name-glyphs of Copan’s Rulers 1 to 6. This is a significant discovery, because little is known of the kings in Early Classic Copan, especially the period from Rulers 3 to 6. Elisabeth Wagner’s study Jun Yop Ixiim – Another Appellative for the Ancient Maya Maize God (Research Note 8) discusses a new reading of the name of a particular aspect of the Classic Maya Maize God. This identification has been made after the documentation of two casts of the Oval Palace Tablet from Palenque in 2015 und 2016.

Christian Prager

Bonn, February 2019

The Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan Staff

Bonn

Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Nikolai Grube (director)

Dr. Christian Prager (coordinator)

Dr. Sven Gronemeyer (research associate)

Elisabeth Wagner, M.A. (research associate)

Katja Diederichs, B.A. (research associate)

Antje Grothe, M.A. (research associate)

Thomas Vonk, M.A. (research fellow)

Céline Tamignaux, M.A.

Laura Heise

Lisa Mannhardt

Christiane Bahr (2014)

Laura Burzywoda (2014-2015)

Nicoletta Chanis (2015)

Dr. Albert Davletshin (2017)

Leonie Heine (2014-2015)

Jana Karsch (2014-2017)

Nikolai Kiel (2015-2017)

Catherine Letcher Lazo, M.A. (2015-2016)

Mallory Matsumoto, M.A. (2015)

Nadine Müller (2015-2016)

Göttingen

Dr. Mirjam Blümm (project board)

Maximilian Brodhun, M.A. (research associate, Göttingen)

Dr. Heike Neuroth (project board, 2014-2015)

Sibylle Söring, M.A. (project board, 2014-2017)

Franziska Diehr, M.A. (project board, 2014-2018)

PROJECT REPORTS 2014 - 2017

PROJECT REPORT 4

Milestone Report 2014 - 2016

Nikolai Grube, Christian Prager, Katja Diederichs, Sven Gronemeyer, Elisabeth Wagner, Maximilian Brodhun, and Franziska Diehr

1. Project Description and Objectives

The Classic Maya hieroglyphic script, which consists of both logographic and syllabic signs, is one of the most significant writing traditions of the ancient world1. As a graphic manifestation of language, writing mediatizes human thought, communication, and cultural knowledge in the form of texts. Deciphering a script allows ideas, values, conceptions, and believes to be reconstructed, and thus permits insight into the memory of past communities. In order to achieve this, the writing system and the spoken language that underlies it must be known. For Classic Mayan, this breakthrough in decipherment has already been achieved; however, in spite of great progress made in recent decades, some 40% of the script’s more than 800 signs remain unreadable even today. One reason for this situation is their lack of systematic attestation. Even in cases in which the signs are legible, texts may still elude understanding, because the Classic Mayan language itself has not survived; instead, it can only be reconstructed through comparison of the 30 Mayan languages documented since European conquest and still spoken today. However, much of the pre-Hispanic Mayan cultural vocabulary has been lost in the aftermath of European colonization. Consequently, comprehensive documentation and decipherment of the approximately 10,000 extant hieroglyphic texts, reconstruction of the language that they record, and documentation of that language in a dictionary are necessary prerequisites for acquiring a deeper understanding of Classic Maya culture, history, religion, and society.

The subject of the project is an incompletely deciphered, complex writing system, which the project aims to decipher with the aid of digital tools and to describe its underlying language in a dictionary. For these purposes, the hieroglyphic texts are being made machine-readable and saved in a text database with analysis and commentary. In addition, the Classic Mayan language is being represented in its original orthography in a web-based dictionary, allowing users to compare the content with its analysis. Until now, no project in the realm of digital writing systems research has demonstrated comparable standards, goals, and qualifications, or could serve as a model for conceptualizing and developing our database. When developing their databases, research projects in Greek,2 Latin,3 or ancient Egyptian4 epigraphy are not faced with the same challenge of their respective writing systems and the corresponding languages being only partially or not at all deciphered. Our goal is to use the digital tools currently under development to compile and register newly classified signs in sign lists, make the texts machine-readable, discern readings, and document the vocabulary in its original orthography. The innovative character of our project requires flexible management when developing the digital infrastructure and deploying financial resources, as well as methodical ground work to develop working concepts that will be useful over the long term. It consequentially affects the project’s work, timeline, and personnel planning in the first two work packages. The project’s outcomes will ultimately include the development of new tools, methods, and standards in digital research on ancient writing systems and even the digital humanities as a whole, in addition to the content it produces about the Maya script.

The project’s emphases on digital epigraphy, database development, and long-term and interoperable storage of research data in particular underscore the great significance of the digital humanities for such an innovative undertaking. Yet the project will also contribute pioneering work to computer-based research on writing systems, and will develop methods and standards that will benefit other areas of research. To this end, it is co-operating with the Göttingen State and University Library (Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek; SUB), which represents the project’s informatics and information technological capacities. The project is assuming an interdisciplinary stance and operates at the intersection between applied informatics and the humanities. In this respect, the project does not merely provide an interface between these disciplines in the realm of digital epigraphy. In addition, it is also giving our research and informatics personnel interdisciplinary skills that they can integrate not only into their work in the project, but also into their teaching.

The collective tasks of the project include documenting existing research on Maya culture in a bibliographic database; collecting, archiving, and organizing hieroglyphic texts; and developing metadata models for describing and annotating the texts. Epigraphic and linguistic analysis of the texts, as well as collecting research data in a database of texts and text-bearing objects, will provide the basis for the aforementioned dictionary, which will comment on the texts and reference all existing bibliographic literature. The database will include original spellings, from which variants and developments in Classic Mayan vocabulary, grammar, and the script can be reconstructed.

Methods from the digital humanities are being employed, and in some cases innovated, in order to complete these tasks and to optimally and sustainably process the large quantity of data. The project is utilizing text mining to recognize textual patterns; identify signs, sequences of signs, or passages; test decipherments in their respective contexts of application; and propose new phonemic values. All of this work is ultimately directed towards the goal of generating a corpus linguistics record of the vocabulary of Classic Mayan in its temporal, spatial, and social dimensions.

The digital working environment is being implemented in the virtual research environment (VRE) TextGrid, where our adaptations and epigraphic tools operate under the designation Interdisciplinary Database of Classic Mayan (IDIOM). The research data will be stored long-term in the TextGrid Repository, and will be made freely available in their entirety via a web portal. In cooperation with the Bonn University and State Library (ULB), select contents from the TextGrid Repository will be published in a virtual inscription archive in the ULB’s Digital Collections, including for instance images of the inscriptions, basic information about them, and analyses and translations.

Text databases and dictionaries are not only being used to document Classic Mayan; in addition, they are also our tools for deciphering the Maya script. New phonemic values or proposed readings for logographic and syllabic signs are being identified and continuously entered into the digital sign catalog. They can be directly tested for feasibility using the texts available in the system. Furthermore, the architecture and implementation of the database and dictionary always take into account the current state of decipherment and thus represent the dynamics of Maya epigraphic research. The writing system is only partially deciphered and many texts cannot be completely read. As such, it is necessary to document all available information about the text-bearing objects, because the meaning of words is their use in context. For this reason, we are gathering information about each text-bearing object and its context (so-called non-textual information) and linking this information to the analysis of the script and language. Maya texts often concern the inscribed object, its position, and its commissioner. Consequently, the materiality and cultural and social context of a text-bearing object provide important insights. We are accounting for these complex relationships between sources of information when designing and building the VRE, and are thus paying particular attention to the VRE’s development and adaptation to the demands of our project.

2. Project Phase I (2014 - 2016) – Documenting and Recording Text-Bearing Objects

The foundation of the project’s textual analysis, which will be the central element of the work package from 2017 through 2028, is created by documenting and recording text-bearing objects. Consequently, the project began by designing and subsequently constructing its information technology infrastructure. When compiling the Classic Mayan dictionary or analyzing the meaning of words, texts should not be considered independent of the object on which they are recorded, nor of their temporal or spatial context. The object and its content provide non-textual information, or metadata, about the text-bearing object itself, its location, neighboring monuments and associated finds, commissioner, and historical context as a whole. These data are highly significant for deciphering and interpreting the inscriptions, and carefully documenting them in the database is a prerequisite for decipherment and text interpretation.

Another essential component of the object database, in addition to its link with the text database, is its capacity to establish and query relationships between multiple texts and text-bearing objects. This feature is significant because a text can extend across multiple text-bearing objects. Such work becomes possible and relations between people, events, and places can be made visible only after very detailed metadata have been recorded. However, the database contains more than just descriptions of the text-bearing objects and their textual contents. With the literature database, the user can access an overview of which authors have studied or published a monument, discussed a text passage, or first proposed to the public a linguistic reading of a hieroglyph or sign that remains valid to this day. By closely cross-linking these data, the project’s work on the text and object database will yield an additional benefit by producing the source material for the project’s ultimate goal: a Classic Mayan dictionary.

2.1. Constructing the Technical Environment for Recording Text-Bearing Objects

Close exchange between the disciplines represented in the project is necessary to create a capture environment that fulfills the scientific needs of the Bonn workplace. Mutually communicating knowledge (epigraphy, linguistics, and ancient American studies on the one hand and data modelling, vocabulary development, and informatics on the other), collaboratively defining and specifying demands, and developing information technology capacities are processes that enhance the transfer of knowledge and information in the project and, above all, significantly contribute to reaching the desired goal.

2.1.1. Analyzing the Project’s Scientific Needs and Developing the Metadata Schema

The Göttingen team modeled the metadata schema for recording the text-bearing objects and historical context based on a collectively specified and professionally evaluated catalog of requirements. This development was an iterative process through which the technical requirements could be continuously redefined. In order to guarantee that our own conceptions were of high quality, the schema was constructed on the basis of established international standards. Reusing pre-existing and professionally recognized terms furthermore contributes to its high degree of interoperability with other data sets and information systems. The structure of the resultant schema is ontologically cross-linked, representing complex relationships and correlations.5

2.1.2. Developing Controlled Vocabularies

A total of 10 multilingual thesauri were developed through interdisciplinary collaboration to scientifically record the text-bearing objects. The Bonn team’s task was to research, select, and define scientifically appropriate terms, whereas development of the vocabularies was supported in Göttingen by the application of methods from documentation science.

In choosing appropriate terminology, all terms that had been previously employed in the literature were checked for plausibility, comparability, and utility. The resultant collection of terms was ordered according to terminological principles and modeled in the SKOS (Simple Knowledge Organization System) format,6 in order that they could be represented in machine-readable format and integrated into the metadata schema. The terms could also thus be simultaneously mapped onto the normed data from the Getty Thesauri,7 which allows the reused terms to be referenced.

Developing the vocabularies is extremely relevant not only for the project’s own work, but also for the discipline more broadly. Until now, a multitude of terms, vocabularies, and descriptive schemas have existed in Maya epigraphy, resulting in a wide range of differentially documented text-bearing objects. The terminology being applied demonstrates relatively little agreement at times and is often incomplete, erroneous, imprecise, or dramatically simplified.

In developing these vocabularies, the project is making a significant contribution to standardization in Maya epigraphy, because it is reusing terms that are already established in scientific research, clearly defining them for the first time, and also situating them in a terminological relationship to one another.

The vocabularies will be published in both machine- and human-readable form on the project’s website by the end of 2016, according to the project’s timeline.

2.1.3. Developing and Designing the Technical Infrastructure

As part of the project’s work, data of various types are being created and stored. Image data, metadata, and text analysis files have to be managed in relation to one another in a single infrastructure with respect to their creation, storage, processing, and access regulation. The VRE TextGrid is being used for these tasks. The frontend TextGrid Laboratory (TG Lab) allows files to be created and processed, as well as fine-grained management of the rights thereto. The backend provides access to the repository TG Rep, which stores the data in a secure environment. The repository is made available by the GWDG and guarantees data storage using long-term digital preservation methods.

The densely networked structure of the files with the metadata for the text-bearing objects requires appropriate storage. This need is met by the format RDF (Resource Description Framework)8 and by storing them in a graph database in the form of a triplestore.

An entry mask is used to record the metadata in a user-friendly manner. This tool is HTML- and JavaScript-based and provides the user with multiple entry aids. When utilized as a plug-in for the TG Lab, the entry mask can be installed and directly used from the TG Lab. Examples of its supporting functions include searches in internal and external databases (to establish object relations), validating entry fields, and automatically converting data formats. Another important support in data entry is navigating within the vocabulary hierarchy, whereby the user does not initially have to search using concrete keywords. The triplestores for storing the metadata and vocabularies, the entry mask, and the project website are being made available on the project server.

2.2. Scientifically Recording Text- and Image-Bearing Objects and Their Historical Context

Since November 2015, the team in Bonn has been documenting text-and image-bearing objects using TG Lab and the entry mask. As part of this work, the research team, with support from the student assistants, conducted a systematic search for all available publications, databases, and websites of collections, museums, and other research institutions. These data form the foundation for recording the objects, a task which can be broadly divided into three components:

Documenting the artifacts (names, identifiers, object type and shape, measurements, state of preservation, and contexts of production, discovery, acquisition, and storage);

Archaeologically relevant places (with archaeological and geographic coordinates, normed and alternative place names) and their classification in a complex hierarchy of places (the place of an object’s discovery and its situation within the architectural context of a structure, the latter’s location in an architectural group in the site, and the site’s situation in the hierarchy of modern political and administrative regional authorities);

Situation in the relevant historical context: events and persons (e.g., wars, monument dedications, accession, ruler biographies, sociopolitical relations).

Recording is additionally supported by controlled vocabularies and references to normed data.9 Furthermore, the information can be supplemented with citations of sources that are supplied by the project’s bibliographic database in Zotero.

The ontologically networked data structure allows complex questions to be asked of the material, for example, which text-bearing objects are situated on Tikal’s Great Plaza? When were they dedicated, who commissioned them, and what historical events are mentioned there, for instance compared to those mentioned on the altars (text-object relation)?

The contents of the inscriptions from the site of Tikal and their associated persons and events have already been registered. Tikal is one of the largest and most significant Classic Maya cities. Tikal (located in the Department of Petén, Guatemala) was selected as our initial test case for object recording, instead of the state of Campeche, Mexico as stated in the proposal. Because Tikal is well-documented in the existing literature, it is well-suited for testing the information technology environment (including the metadata schema, entry mask, and data querying) against the project’s research demands. The text-bearing objects from Campeche, in contrast, are scattered between multiple sites and have in some cases been only superficially described in publications.

We began documenting texts from the state of Campeche as per the proposal in the second half of 2016, and have recorded the metadata for the texts from the site of Calakmul. In addition, we have just started to record artifacts from the sites whose inscriptions have been documented in the over 20 fascicles published by the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Project since 1975. The database currently10 includes 597 artifacts connected with 76 discovery events, 88 production events, 2 acquisition events, and 56 storage events, and 439 places, all in various stages of recording. We have also entered an additional 25 persons and groups (including researchers, curators, and museums) relevant to the artifacts’ research histories and provenience, and 302 individuals (mostly rulers) and 91 epigraphically attested events related to their historical contexts. The total number of entries in the database thus amounts to 1706.

2.3. Documenting and Digitizing Research Materials

Texts and the objects on which they are recorded together constitute the project’s research subject. Thus, the text-bearing objects themselves must be researched as well. Because they are geographically dispersed and in many cases cannot be moved, they must be digitized in high quality in order for research to be conducted effectively and transparently. This approach facilitates data exchange and permits collaborative research from multiple sites.

In order to conduct epigraphic analysis in a VRE, the unit of text plus text-bearing object absolutely must be digitally available, and thus first digitized if necessary. Unpublished research should be accounted for in the same manner. Descriptions or epigraphic notes, which are essentially “analog metadata” that can be re-used, are available for many archives. These materials also must be digitized and can thus be made available for research for the first time. The project additionally is producing its own digital research materials.

The materials being documented originate from archives both in Germany and overseas (e.g., Ibero-American Institute in Berlin, Carnegie Institution of Washington via Artstor). The collections of Prof. Karl Herbert Mayer and Emeritus Prof. Berthold Riese provide particularly important private archives.

In parallel to this work, the Bonn team is gathering detailed information in working lists, which include a concordance11 of all existing sign catalogs and classifications; lists of sites, museums and collections, text-bearing objects, grammatical morphemes,12 and lemmata; and an inscription archive that comprises all text-bearing objects with comments about the inscription and chronology is also kept on file in paper form.

2.3.1. Digitizing the Archival Materials

Berthold Riese’s inscription archive consists of 135 binders containing photographs, drawings, and epigraphic notes; as of the time of writing, just about one-third of the materials have been digitized in over 14,000 files. At present, over 20,000 of the ca. 40,000 images (slides, negatives, prints) from Karl Herbert Mayer’s photographic archive have already been digitized as well. The project’s research materials are additionally supplemented by the team members’ private holdings, as well as donations from colleagues such as Dr. Daniel Graña-Behrens and Stephan Merk. The materials are being digitized with scanners by undergraduate assistants in Bonn and supplied with metadata by a graduate assistant. We expect a total of over 70,000 documents to be scanned and integrated into the digital archive over the coming years.

2.3.2. Documenting and Digitizing Inscriptions

Traditional methods, such as photography and drawing, as well as newer techniques like photogrammetry and 3D structured light scanning, are being used to document the inscriptions. Compared to existing imaging procedures and measuring techniques, documenting and measuring artifacts with a 3D scanner prove to be particularly advantageous for epigraphic research. 3D scanning permits thorough examination of the numerous eroded inscriptions that are no longer readable to the naked eye and cannot be rendered legible using photography and subsequent image processing. Detailed features can be more easily recognized with virtual manipulations (e.g., simulating lighting from various angles). In addition, fragmented text-bearing objects can be virtually reconstructed, and data acquired from application of earlier methods can be supplemented and refined. Documentation and measurement procedures also require notably less time for each individual object than do pre-existing techniques. Furthermore, 3D scanning contributes to archiving and storing existing cultural heritage in a form that is true to the original. 3D scanning is thus an essential component of the documentation trips to archaeological sites, museums, and archives that are undertaken by the project, as specified in the proposal.

The project places particular emphasis on collaboration with museums and collections whose inventories include artifacts with texts that can be scanned for epigraphic analysis and published as a 3D object. The 3D objects are made available to the museums after they have been processed, compiled, and rendered with software. As early as 2015, the project has used these methods to document Maya artifacts from the exhibition “Relief Collections from Great Ages” (Reliefsammlung der großen Epochen) at the Knauf Museum in Iphofen, as well as the wooden lintels from Tikal held at the Museum of Cultures in Basel. The trips during which this documentation was conducted occupied 3 work days in 2014 and 68 work days in 2015, and are expected to occupy 46 work days in 2016.

2.3.3. Compiling the Bibliography

The free and open-source application Zotero is being used to collect, manage, and cite diverse online and offline sources, thereby documenting the existing scientific literature. This application supports editing and processing of bibliographic citations and lists, as well as collaborative work from multiple locations. The bibliographic database currently contains almost 16,000 entries and is being continuously expanded, with an anticipated eventual total of 70,000 entries. The contents also being regularly revised and tagged by theme.

3. Presentations and Publications

The project is working to promote timely, open, interdisciplinary, collaborative science. To the greatest extent possible, the project strives for completely open access to its scientific publications (“Open Access”), documentation of its methodology and work procedures (“Open Methodology”), as well as its research data (“Open Data”) and the software used by the project (“Open Source”), in accordance with “Open Science”. Unimpeded access to the project’s research, as well as a guarantee of productive re-use, must be achieved using free licenses.

For this reason, all data compiled in the context of the project are published online under the internationally valid Creative Commons copyright license CC BY 4.0 “Open Access”.13

The project strives to make accessible all digitized images and drawings of Maya monuments from various publications for which the project has received or purchased the rights for worldwide publication. These images, together with annotated metadata, will be made available online in the TextGrid Repository and Portal, along with citations of the original sources and authorship. Digital images and publications whose rights are restricted will at a minimum be made available for research purposes within the TG Lab to a registered group of scientific users.

The individual “Open” strategies feed into or necessitate each other in the project’s work process. The project thus uses several different platforms on which methods, research results, data, and metadata developed over the course of the project can be shared, published, and made available for continued use.

3.1. Website, Social Media, and Portal

The project’s website,14 which was released in 2015 and is based on WordPress, serves as the project’s principal platform for online publications and guarantees rapid dissemination of its research results at no cost. The German National Library has registered our internet presence as a publication platform.15 Current work on lexicography, decipherment, and linguistics are published in the sections “Working Papers”, “Research Reports”, and “Project Reports”, along with working papers and concept papers about the use of tools from the digital humanities in epigraphy. In collaboration with the SUB, the project established a workflow for registering a unique digital object identifier (DOI) to ensure the long-term referencing and citeability of these digital objects. The DOI references the object itself, not the storage location (URL).

Another aspect of the website, in addition to special case studies, is rapid and broad dissemination of research data in the section “Documentation” (e.g., site list, sign concordance, 3D meshes), as well as announcements and general information about the project.

Furthermore, communication with users is critical: all research data that result from the working lists allow the potential for feedback that is intended above all for quality control purposes. An additional component is discussions about the online publications, which can be publically commented to foster scientific discourse.

In addition to our website, social media channels play a significant role for the project. Channels on Facebook16 and Twitter17 went online at the same time as the website. Sketchfab18 offers not just a platform for 3D models, but also its own models, and other users’ models can be shared and linked as well.

Furthermore, beginning in the second quarter of 2018, the project intends to develop a portal that not only presents the data from TextGrid, but also enables fine-grained searches. The portal will be accessible via the website, but technologically independent from it. Eventually, all of the research data created in the project and current working versions of the dictionary will be made available on the portal. In addition, the portal will offer targeted search functions that permit complex queries of the TextGrid Repository containing all of the textual and non-textual metadata mentioned in Section 3.2.

3.2. Using and Adapting the ConedaKOR Image Database for Registering Digital Materials

An essential component of the project’s work is publishing the data it has recorded and compiled. In particular, the research material donated to the project that has been documented and digitized and concerns Maya non-textual objects and materials (see Section 3.3.1) needs to be managed, archived long-term, and made publically accessible for research. For this task, the project will employ its own image database in ConedaKOR19 as an additional publication platform. In ConedaKOR, the digitized archival materials, such as uninscribed utilitarian objects, artifacts, and architecture from the Classic Maya, are arranged and represented in relationship to one another. Beginning in late 2016, the project has been developing a metadata schema and testing the process of recording stored contents in its own ConedaKOR database, using selected digital images. The plan is to develop and represent in the given graph database a metadata model oriented not towards the digital images, but towards the represented entities (e.g., artifacts, places, people). The contents should be linked with metadata to bibliographic references, in addition to descriptions of the object’s history. For this, the project will again use its Zotero bibliography, which will be technically linked with the data structure. In the future, access to our ConedaKOR database in the DARIAH infrastructure should be possible via a web service.

3.3. The Inscription Archive in the Digital Collections of the ULB Bonn

In collaboration with the ULB Bonn, the project intends to develop an inscription archive for Classic Mayan in ULB’s Digital Collections.20 The archive will present the text-bearing objects documented by the project with their digital images and object-related metadata, as well as their inscriptions with transcriptions and translations.