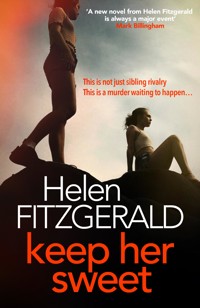

Keep Her Sweet: The tense, shocking, wickedly funny new psychological thriller from the author of The Cry E-Book

Helen FitzGerald

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

When a middle-aged couple downsizes to the countryside for an easier life, their two daughters become isolated, argumentative and violent … A chilling, vicious and darkly funny psychological thriller from bestselling author Helen FitzGerald'Sharp, shocking and savagely funny. Helen Fitzgerald is a wonderfully original storyteller' Chris Whitaker'A new novel from Helen Fitzgerald is always, a major event … magnificent' Mark Billingham'I devoured Keep Her Sweet … shite parenting and a dysfunctional sister relationship goes to fatal extremes' Erin Kelly–––––––––––––––––Desperate to enjoy their empty nest, Penny and Andeep downsize to the countryside, to forage, upcycle and fall in love again, only to be joined by their two twenty-something daughters, Asha and Camille.Living on top of each other in a tiny house, with no way to make money, tensions simmer, and as Penny and Andeep focus increasingly on themselves, the girls become isolated, argumentative and violent.When Asha injures Camille, a family therapist is called in, but she shrugs off the escalating violence between the sisters as a classic case of sibling rivalry … and the stress of the family move.But this is not sibling rivalry. The sisters are in far too deep for that.This is a murder, just waiting to happen…Chilling, vicious and darkly funny, Keep Her Sweet is not just a tense, sinister psychological thriller, but a startling look at sister relationships and they bonds they share … or shatter.––––––––––––––'A wonderful book about a toxic family … funny, shocking and full of heart. FitzGerald at her coruscating best' Doug Johnstone'Definitely one for those who love deadly dysfunctional families, whip-smart writing, and their stories dark, dark, deliciously dark' Amanda Jennings'A novel rippling with power and intensity. A true page-turner' Michael Wood'Wickedly funny, breath-stealingly tense and utterly chilling … a book you'll want to talk about' Miranda Dickinson'Helen Fitzgerald has an uncanny ability to balance savagery and hilarity … an absolute banger of a book' Matt Wesolowski'A crazy but addictive, dark and funny, read' Louise Beech'Dark humour sings from the pages' Russel McLean'A fascinating and original tale of a family in rapid decline' Jen Med's Book ReviewsPraise for Helen FitzGerald*Worst Case Scenario was Guardian, Telegraph, Herald Scotland AND The Week BOOK OF THE YEAR**Sunday Times TOP 40 Crime Novels in the Last 5 Years**Longlisted for Theakston's Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year Award 2020*'The main character is one of the most extraordinary you'll meet between the pages of a book' Ian Rankin'Sublime' Guardian'A dark, comic masterpiece which manages to be both excruciatingly tense and laugh out loud funny at the same time' Mark Edwards'Urgent, angry, absolutely terrifying, yet suffused with the humanity and humour you expect from a Helen Fitzgerald novel' Erin Kelly'Tantalisingly powerful' The Times'Ash Mountain is the author at her masterly best … I loved it!' Louise Candlish'The classic thriller gets a hell of a twist' Heat'FitzGerald writes like a more focused Irvine Welsh or a less misogynist Philip Roth' Daily Telegraph'Domestic life is rarely served up quite so dark as this – but that only makes you hungry for more' The Sun

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 312

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Desperate to enjoy their empty nest, Penny and Andeep downsize to the countryside, to forage, upcycle and fall in love again, only to be joined by their two twenty-something daughters, Asha and Camille.

Living on top of each other in a tiny house, with no way to make money, tensions simmer, and as Penny and Andeep focus increasingly on themselves, the girls become isolated, argumentative and violent.

When Asha injures Camille, a family therapist is called in, but she shrugs off the escalating violence between the sisters as a classic case of sibling rivalry … and the stress of the family move.

But this is not sibling rivalry. The sisters are in far too deep for that.

This is a murder, just waiting to happen…

Chilling, vicious and darkly funny, Keep Her Sweet is not just a tense, sinister psychological thriller, but a startling look at sisterly relationships and the bonds they share … or shatter.

KEEP HER SWEET

HELEN FITZGERALD

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

The Therapist

Unhappy families always cheered her up. Joy was smiling and she hadn’t even met the Moloney-Singhs yet. She had walked past their house, though, hundreds of times, but had never noticed it really, even the engraving at the top: JB Collins, ESTABLISHED 1895. It was a bluestone fortress with bars on its meagre ground-floor windows, and was incongruous, sitting as it did between two detached verandaed weatherboards. Joy had Googled ‘JB Collins’ before the visit, thinking it the wrong address, but there was hardly anything online. Maybe it was originally used to store grain and groceries, like the infamous Pratt’s on Mair Street. After the session she would get in touch with Anne McLean – no Frank Peters, at the historical society. One thing she did find online was the ‘For Sale’ advertisement from twelve months prior:

‘Chic, romantic artist’s retreat in converted nineteenth-century warehouse in the centre of historic and vibrant Ballarat, just a short walk to galleries, theatres, bars, parks, cafés, restaurants, shops and Lake Wendouree.’

The accompanying photographs showed a bright, minimalist interior with soft lighting and low, squidgy sofas. Joy was looking forward to getting inside – the outside was glum.

She had Googled the family too, as she always did nowadays, and wished she hadn’t. She knew too much about the Moloney-Singhs to be fresh and non-judgemental – such as the fact that they lived in Preston for twenty years before moving here (and had perhaps overestimated the happiness ‘architecture’ would bring).

Second-born let her into the cavernous exposed-stone hall. Her name was Camille. She was polite and had a bruised nose. Joy knew from her mother’s email that she had just finished studying English and theatre studies at the University of Melbourne and had moved home temporarily to save for her travels.

To Joy’s surprise, the inside of the house looked nothing like the pictures she’d seen online. The lighting was stark and hurt her eyes. There were no squidgy sofas and there was stuff everywhere.

Camille led Joy to the other end of the hall and offered her a seat at the table.

‘Your mum says you’re planning to go backpacking,’ Joy said. ‘Where are you going?’

Before Camille could answer, First-Born pounced from a windowless room off the hall. Her name was Asha. She was almost identical to her younger sister except that every element that Joy could see was ever-so-slightly askew. She was twenty-four, and Joy knew from her mother’s ‘urgent’ email that she usually stayed in Sunshine but had recently been placed on an electronic tag at ‘our new (over-stretched!) house’.

Joy could see the contraption on Asha’s ankle – it had been graffitied and signed, as if it was a plaster cast. There were scratch marks surrounding it. She looked like she hadn’t been outside for a long time and could do with some broth.

‘She’s going backpacking in Werribee,’ Asha said, slamming herself onto the chair opposite her little sister and knocking the table off balance. ‘Six months rent-free and she’s saved two hundred and thirty-seven dollars.’

‘How do you know how much I’ve saved?’ Camille asked, trying to remain polite.

The vibe was so toxic that Joy was positively beaming inside. Her family was not so bad. Her life was not so sad.

Camille eventually broke the silence. ‘Mum and Dad are late back from hot yoga,’ she said, without shifting her glare from her sister.

Joy couldn’t look at the girls, so she took in the hall. Someone was trying to thrust a purpose on it, but she wasn’t clear what. Photographic studio? Workshop? Art gallery? Retail space? There was a glittery dress on a mannequin, shelves with jewellery and pottery and candles on them, and galleries of paintings all over the stone walls. There were tags on almost everything in the room, including the upcycled table she was sitting at ($2,457).

‘Everything in the house is for sale,’ Camille said.

‘Really?’

‘My parents are setting up a “content house” – well that’s this week’s plan,’ she said, waiting for Joy to understand. ‘A “hype house”, like the Tik Tok Mansion in LA but for Gen-X empty-nesters.’

‘And in Ballarat,’ Asha said, the word somehow scathing.

‘Oh,’ Joy said. (She would need to do some more Googling later.) ‘What happened to your nose?’ she asked Camille.

‘Netball injury,’ the girls said at exactly the same time.

The chemistry between them was making Joy’s legs fidgety, so she resumed her scan of the space. She could smell stale coffee coming from the back end of the house. She couldn’t see beyond the hall but knew from Google that it opened into a bright open-plan kitchen/living area with a huge mezzanine bedroom above. There were two rooms off the high-ceilinged hall she was sitting in: the windowless one Asha came out of, which had two single beds in it, and another with a high, barred window that was jam-packed with the most extraordinary array of objects: huge, steel pottery wheel right in the centre, desk, clay, piles of yellowing newspapers, sculpting tools, easel, clothes rack, paints, brushes, sewing machine, remnants, packing materials. If this was a memory game at a birthday party Joy would be winning. The chair she was sitting on was hard and rickety, and $355 was a crazy price for it, no matter what was painted on the seat (fifties housewife, holding a teacup).

Asha and Camille seemed to be having a staring competition across the table, and it was a relief when Mum and Dad arrived.

Mum’s hair, and much of her hand-painted silk kaftan, were wet with sweat, which sprayed off her as she took her seat at the head of the table, exhaling as if she was exhausted with having to make feminist seating statements. Her name was Penny and she was fifty-four. Her email had sounded desperate. To do this visit today, Joy had actually rescheduled family number two – the McDonalds, whose third- and fourth-borns enjoyed driving like maniacs at ‘hoon meets’ and were in trouble with the law.

‘My youngest, Camille, suggested I get in touch re family therapy,’ Mum’s email had read. ‘After the girls left home, my husband and I moved here with such excitement, and it has turned into a living hell.’

Dad, Andeep, fifty-seven, could not decide which daughter to sit beside, finally choosing to shove a chair at the end next to his wife. Joy knew from Google that he was a successful stand-up comedian in the UK in the nineties, but made some kind of filthy blunder on live television and had moved to Melbourne to be near several other disgraced comedians. She also discovered online that Andeep had recently started teaching a stand-up comedy course at the Eureka Theatre in town.

‘I hear you’re setting up some kind of contents house?’ she said to Andeep.

‘Ha, content, well yes, the ideas are evolving all the time.’

She was a little shocked at his accent; she did not expect him to sound like Billy Connolly.

‘Penny’s an artist. She made everything here – that lamp, that was her, the shade anyway I think, yes, baby? Yes. All those paintings, that bowl – Not that one? Almost everything you can see. And I’m a comedian. We thought we could combine our skills.’

‘Like they do on all those shows,’ Penny said. ‘You know: people are baking profiteroles or blowing glass, and someone’s walking around telling jokes at them.’

From her tone, it didn’t seem Penny had much confidence in the idea.

‘The girls are going to help us set up a YouTube channel,’ Andeep said.

‘You haven’t filmed anything yet,’ Asha said.

‘It’s evolving’ / ‘It’s a work in progress,’ Penny and Andeep said.

Joy did the usual introduction about her experience and qualifications. She told them she’d lived in Victoria for forty-five years – despite her strong English accent – and was still working at seventy because she loved helping families work things out. She really did. It wasn’t like relationship counselling, which Joy only dipped into when she was desperate for work. It never started with the question: ‘Do you want to stay together?’ Families don’t ask that. Families are forever.

Spiel over, Joy asked them to take turns to say – in one or two sentences – why they were here. Penny didn’t wait for the silence to get awkward:

‘I think we’re here because there are too many ideas in the house.’

Joy gave Penny a reassuring nod – there were no wrong answers – while marvelling that every idea in the space appeared to be hers.

After a brief pause, Andeep said, ‘I think we’re here because … Why I think we’re here … One or two sentences…’ He was thinking very hard. ‘Okay, so I am starting to realise that it must be very difficult having a famous father.’

Andeep’s wife and first-born, Asha, erupted into laughter. Asha choked on a sip of water.

Camille couldn’t help smiling. It seemed to hurt her. She held her stomach.

Andeep tried to disappear into his chair.

‘Asha?’ Joy bit her lip. ‘What about you, why do you think we’re here?’

Asha calmed herself and took another sip of water: ‘I think we’re here because Camille made us come here.’

It really was so hot in that hall. Joy was finding it difficult to focus. ‘Camille,’ Joy said to the second-born, ‘why do you think we’re here?’

Camille took her time to think about it – she was very like her dad – then sat up even straighter than before, leaned in towards her older sister and said, ‘I think we’re here because she broke my fucking nose.’

CHAPTER TWO

The Mum

Penny was into therapy. CBT, for example (first and twelfth year of marriage); as well as psychotherapy (post baby blues with child number two); and marriage counselling (year twelve again, that was a tough time. Andeep had abandoned her to wail by his mother’s death bed in Glasgow, for seven months). But this one, family therapy, had made her so nervous she did a vomit-swallow during the hot plank. She wished she’d never emailed the therapist and had only done so because Camille went on and on about it to her and Andeep, and she wanted to gain the upper hand. When they had marriage counselling, Andeep made the appointment, and the therapist was so on his side the whole way through. Penny exhaled. She definitely wasn’t the bad guy this time. Also, the therapist was an older woman so might be more inclined to see through the lovable façade and see the true man who was her (all right, whatever) lovable husband. She stretched and breathed. The sessions might help her. But with what, her habit of point scoring? Penny had recognised it as an issue in CBT no.2 and had since done Very Well at not doing it. Perhaps she was terrified of being accused of poor parenting. This seemed unfair when she had done absolutely everything in her power to be a good parent all the way to the finishing line. She only ever worked part time, for example, right up till they left school. She had wanted to drop them off and pick them up and ferry them round and feed them food. She had wanted to read them stories at night and make mud pies with them and go to parent-teacher group and organise play dates. She had wanted to be a good mum, and she was. She had given herself over to it completely.

Sometimes she had to look through old photos to remind herself of all the above – and indeed there was a lot of evidence of her excellent parenting. There were so many photos of the meals she had made, for example. Andeep always insisted on snapping a shot of the table before they started eating, so there were hundreds of photos of picnics, barbecues, beautifully laid table after luscious food-filled table – in the garden in Preston, in the kitchen in Preston, in the holiday house in Portsea, in the tenement in Glasgow. In every photo she was smiling – a genuine beaming smile – because she loved hard work and she loved being a mother and she loved food. Penny added it up and estimated that she had made at least twenty-one thousand meals since having children. This meant she had probably smiled genuinely more than twenty-one thousand times, and therefore could again.

Andeep held her hand all the way home, a hold that had become more and more of a hand brake since they decided to create the perfect life. He was using all his energy to slow her down, and she was using all hers to pull him along this allegedly beautiful boulevard.

She had imagined this walk from yoga a great deal before the move, and they had walked a lot faster than this, and when Andeep stopped to chat to a friendly country local, he had said something really funny that she had never heard before. Penny had imagined a lot of things about Ballarat differently – much of her knowledge based on satellite view. She realised now that everything looked lovely in satellite.

Andeep pulled the hand brake on full to wave at Brendan Valencia from Mount Clear, who they had absolutely no time to talk to. Penny breathed in and zoned out, ‘almost as if you’re inhaling smack,’ a counsellor with burgundy hair had said to her once; ‘let everything go blurry.’ She was really good at this now but could never do it for very long.

‘And your third wish?’ Andeep was saying to Brendan Valencia from Mount Clear in a genie voice that he had perfected in August 1990 and which had lost its zing in September of the same year. ‘Tell me, what is your third wish?’

Penny squeezed his hand gently and looked at the time on her phone, but he did not take the hint. A good thing probably, because whenever she squeezed his hand like this, or kicked him under the table at a dinner party – despite lengthy discussions regarding secret codes beforehand – he would without fail loudly announce: ‘Why’d you kick me under the table?’ She didn’t squeeze again – risky. She was Ballarat Penny now and she could listen to the rest of her partner’s joke and work towards enjoying it. She would start with a fake smile. ‘A fake smile might well turn into a real one,’ a counsellor dressed in yellow had said to her once. The genie joke was a particularly long one though.

She’d never admitted it to Andeep, but when she saw him at The Comedy Lounge for the second time, she was devastated, and a little ashamed, that he was repeating the same routine. One-quarter of a joke in and she thought he was having a panic attack, why else was he being unspontaneously unfunny? As she’d only been to two live comedy shows previously, she didn’t realise that, really, they were all just reading the same thing over and over. In her close-knit extended Irish family, repeating jokes was up there with being English. Andeep still told the same set of twelve jokes to this day, and it was difficult when people didn’t understand why Penny did not laugh.

The joke wasn’t over and she was late and vomitous. The children would be present at this counselling session – for the first time ever – and may say anything. Children – they were enormous adults, suddenly and indefinitely expecting her to make thousands and thousands of meals again.

If only they were still children – she would have been able to prep them for family therapy first. She would have been able to ask, bribe, no tell, them not to mention the time she ran away to the garage, for instance, when Twin-Pearls Janey had to break the window to wake her because Little Asha was playing teachers with Camille and punishing her with a fly swat. Andeep was at the Adelaide Fringe again at the time, an annual career essential that cost them four times what he ever made. Penny loved that garage. Apparently she had been asleep in it for five hours when Twin-Pearls clambered through the broken window and landed on her.

Brendan Valencia’s laugh seemed genuine, Penny confirmed to Andeep, twice. Cheered, he eased the hand brake the rest of the way home.

Thankfully, the girls were so angry at each other that they didn’t mention the garage incident, nor the time Penny smacked Camille for stealing her sister’s favourite waistcoat then staining it with raspberry sauce then using green fairy liquid to completely destroy it almost as if on purpose. Penny wasn’t in trouble in family therapy at all, particularly after Camille said the F-word. Mrs Salisbury recoiled and coughed, and paused for an uncomfortable amount of time. She was very old fashioned – Mrs Salisbury. She then went on about the importance of siblings, that they are your only shared historians, the longest relationships you will ever have and should therefore be nurtured forever like her relationship with her beloved little sister, Rosie, even though she’s so far away…

Penny zoned out. She needed to call her big brother, James, it had been way too long. She imagined him and little Frankie wrestling on the gold lounge carpet in Coburg, everyone laughing and taking bets, but never on Frankie. Frankie was the youngest of the three boys (Penny’s mum stopped when she finally had a girl), and he always needled and whined and picked fights – just like Camille – even though he knew he would end up pinned down. It was like he always wanted to play the victim. Penny smiled as she recalled the rules of engagement for wrestling and other games in her childhood home. James wrote them on the wall of the treehouse one summer. She was so excited finally to be included in their big-boy adventures. The rules were thus:

No weapons.

No groins.

No nipples. (Penny’s idea.)

No heads.

Not on your birthday. (Frankie’s idea.)

It was Frankie’s twelfth birthday that day.

And James agreed … that this would be the rule ‘from tomorrow onwards’. Poor Frankie.

It made her smile, which was inappropriate, she realised, as the table came into focus once more. The therapist was talking about support and action and negative words. She finally ended by giving everyone tasks to complete before the next session, some the same, some tailored. Great, exactly what Penny needed. Homework. Most of which stomped on her needs, like giving up her studio/office so the girls could have some space. This house had seemed perfect for the two of them, a groovy creative oasis with a workspace for each of them off the oversized and underused hall. It simply did not work for four people. Fine. She’d get her homework done quick smart, she decided, because it would be a good idea to give the girls some space. She and Andeep could visit poor Frankie in Laverton, or even James in Balwyn. No, a mini-break would be better, for everyone. When Mrs Salisbury finally left the building, Penny raced up to the mezzanine and eyed a five-star cottage overlooking marsupials and a creek in Hall’s Gap. The girls would have the house to themselves for a couple of nights. To contribute – this was not an allocated task, by the way, the girls were not required by Mrs Salisbury to help in any way – to contribute, the girls could prepare the hall for the open house on Saturday and help with cocktails and receipts on the day. Such a good plan. Even if Penny only managed to sell the retro side-table, she would have covered the costs of this much-needed break. She had rescued the mid-century piece from a car-boot sale in Buninyong and was almost finished painting it gold. In fact $2,000 was stupid, she should be asking at least three. They could go after lunch. Before then she’d whip up a sexy black dress on the Singer. Hall’s Gap, yay. You never know, Andeep might find some new material.

CHAPTER THREE

The Second-Born

I’m sposed to write down why it happened, the netball injury, and I’m having difficulty finding the beginning. It’s just for me, so I know I can write anything, but it’s a hard question, why. Even harder is when. Not last week when we did chest passes in the courtyard. Way before then. For inspiration I’m scrolling through our family group chat. It’s illuminating; it’s like a complete history of the Moloney-Singhs. Mum set it up six years ago when Asha left for uni in Sydney. For a few years it was lovely. We were all doing fun things and posting positive messages and funny gifs. I was missing Asha like mad but was also loving being alone with Mum and Dad. She got her time with them when she was little. It was my turn, and I milked it. We started going out for brunch on Sundays. Mum and I got into upcycling furniture. Dad took me to The Comedy Lounge once a month, and we watched movies every night on Netflix. And Asha was enjoying Sydney. She had a nice boyfriend for a while. Maybe she would have passed her final year if he hadn’t ended it with her. That’s when Asha became a stranger, when she returned from Sydney feeling like a total failure. She was not used to being a failure. If only she hadn’t met that guy, if only she hadn’t moved to that house of weirdos in Sunshine, if only that crazy church hadn’t got hold of her. So many If Onlys. I am starting to think about Asha the way Mum talks about her little brother, Poor Frankie. Poor Asha.

Our group chat is called Nucular Family, which was kind of funny at the time but not now we’re cooped up in this bunker. I’m shocked, reading over it. There has been a huge change in all of us, mostly in the last two weeks, but I can tell it started deteriorating three years ago when I left Preston to live the student life. Mum and Dad were on their own for the first time in twenty-three years. For a while Mum posted family photos every day, at least two a day, and we all felt and said the right things like ‘aww’ and ‘ahh’ and ‘how cute are we’, but after a while Dad stopped responding and Mum stopped posting. There was a lull till lockdown happened, then we all chatted heaps. I was living in North Carlton, Asha was in Sunshine, Mum and Dad in Preston. We sent recipes and TV suggestions and jokes and photos and links to TikToks and pictures of food and of things we were growing in our gardens. That tailed off after six months or so. Chat was now for important information only, like birthday dinner ideas and information about Mum’s plan to semi-retire. She sent us links to crazy houses that they could buy outright: a houseboat on Lake Eildon, a converted tram plonked in a field near Seymour, a treehouse in Daylesford. (Guess it’s lucky we’re in this place and not on a houseboat – one or more of us would defo have drowned by now). Mum had itchy feet and was so excited. Dad didn’t respond to the new-house ideas much. In fact, I’m just realising that he stopped posting altogether a year ago. He didn’t even respond to our messages – not even a like or a love heart. Shit, he didn’t even read them. His wee photo doesn’t pop up at all. Not one time in twelve months. Can’t believe I never noticed that. He just skedaddled, unofficially. I guess if he left the group officially we’d all see it in writing and it’d look way bad: ‘Dad has left the Nucular Family.’

After Dad stopped reading, Mum stopped posting, except to put a love heart on every comment that Asha and I made. Just a heart, that was all. Looking at it now, it’s obvious that Dad and Mum had both left the group. I miss Mum. She used to make beautiful roast dinners on Sunday. She used to take me to get my nails done. She used to find things funny. Now she watches true crime all day and drinks too much wine and looks like she just wants us all to go away.

I don’t blame Mum and Dad for abandoning the family group chat, actually. Since Sunshine and lockdown, Asha had been sending prayers and hymns and links to church zooms. She was anti-vaccine too, till her boss gave her an ultimatum. She started spouting stuff about freedom that made the three of us very uncomfortable. Then there was the time I sent a message to Nucular Family that was intended for Mum only – something like: ‘Are you going to let Asha go on like that? Bonkers. You need to step up and tell her off.’ This sparked a separate thread between me and Asha that was not pretty and ended with us vowing never to discuss politics or religion again.

At that time, I set up a chat with Mum and Dad only, which I did not name and which we rarely used, not till I left uni and had to follow them here.

I wonder if other splinter groups formed at this time: did Asha set one up with Mum and Dad? Did Dad send messages just to Mum? Did Mum message Asha but not me?

No-one uses the family chat anymore. I messaged everyone to remind them about family therapy, but no-one messaged back. I think they’ve all muted it.

My stomach is sore. I wish I could put something on it, like Savlon or a bandage. Just gonna pop on a looser T-shirt, see if it works – hang on.

Sorry bout that.

So, when did it all start to go so wrong that I wound up with a broken nose? Last week? Three years ago? Or even earlier, like my eighth birthday? That’s what comes to mind as the beginning. Maybe just because of what’s going on with my stomach area. The loose top is not working. Gonna try a tight singlet then put a pillow on it.

That’s a bit better I think.

My eighth, so she was eleven. Dad had been away in Glasgow for months. Mum had been spending a lot of time in bed or in the garage. Asha was taking me to school and back, stuff like that. She used to pack me lovely lunches, surprises wrapped in cling wrap, like roast-beef sandwiches and slices of apple. And she organised and presided over my party, which was wonderful right to the end. I invited my five best friends, played innocent girl games like pass the parcel and remember the things on the tray. We danced and ate fairy bread and no-one cried, not even Sarah who was the most sensitive of my friends. I remember Asha propped Mum up on the sofa, and she acted all parental when the adults dropped off and collected their daughters.

Maybe Asha was really tired after the party. So much work. She’d even made me a chocolate cake, which was gorgeous even if it didn’t rise as much as she hoped it would. She got Mum to bed, and when she came back to the lounge she was different.

‘Truth or dare,’ she said.

‘I don’t want to play any more games,’ I said. I was tired too. And I was watching something I liked on the telly.

‘Oh go on, you start.’

‘Truth or dare,’ I said, still watching the telly.

She chose truth.

‘Have you got a boyfriend?’ I asked.

‘Not yet,’ she said, ‘but there’s a boy. Wes. I think about him all the time. He’s good at footy, I’ve watched but I don’t think he knows I have. Nice hair if he used wax or maybe gel on it. Quite tall already, he’ll go to six foot I reckon, his dad’s tall. I know he likes me because he told his mate Georgie, who told Beth from netball. Now your turn, truth or dare?’

I also chose truth.

‘Why do you hate your…’

(I can’t even write it down)

‘…belly button?’

The question made me sick. I didn’t know she knew it was a big deal, for a start. But mostly I didn’t want to talk about you know what. I didn’t answer her, and before I knew it she was sitting on me and pinning my arms down and lifting my party dress and squeezing toothpaste into my you know what.

I screamed. I couldn’t breathe.

When she finished she got off and headed to her room. ‘You need to grow up, Camille. It’s ridiculous, you’re eight now.’

I remember looking at my stomach area – there was toothpaste all the way in it, it was filled. The jaggy edge of the tube had scratched the inside of it and everywhere around.

I pulled my dress back down and put a pillow on top of my tummy and cried. I tried not to think about it – and after a few days, I almost managed.

Do you know what? I bet there’s still some toothpaste down there, but I will never check.

There’s a word for this kind of phobia, but I can’t remember what it is. If I Google it, pictures come up and scare me away. I don’t need to know the word for it anyway.

That’s incident no.1, I’d say, which led to incident no.2:

It was my twenty-first. One month ago. Asha was living in Sunshine and seemingly on top of the world – a city girl, with a job, flatmates she adored and vice versa – even some new guy she was crazy about. To celebrate, she organised an action-packed girl’s day out. She met me at Southern Cross Station and we hugged and giggled, so happy to see each other. We had brunch at Southbank, manicures in Collins Street and did some fabulous shopping in the Burke Street Mall (I got a white fluffy jumper, which I love). By late afternoon we were drinking cocktails on a roof in Lonsdale Street. And then tequila shots at a pub somewhere dodgy, can’t remember where. We were heavily pissed by the time she took me to a secret location for my actual present, which she was so excited about. We had to walk arm in arm to stay upright, and we were singing. She stopped in a side street filled with independent shops and handed me a small gift. I hugged her. She had already given me so much. When I opened it I was so drunkenly in love with her sisterly generosity. It was a jewellery box. How sweet.

I opened the box and pondered. One large, gold, hoop earring. Just one. I was about to remind her I don’t have my ears done when she looked at my tummy and then at the shop we were standing in front of. Piercings.

Inebriation and fear came over me. She saw it, held my hands: ‘You can do this, Cammy, you can do this. No more fear. I’ll sit with you.’ She took her flask out of her bag and said I should take a swig for courage, which I did. Which I fucking did, because I am an idiot and a fool.

Fifteen minutes later I exited that little shop with a piercing in my … Oh god, it is so hard writing this down. I don’t want to. It’s stupid writing things down. And this tight singlet is making it itch, I mustn’t touch, scratch, oh god oh god.

I’ve had it for a month – four weeks! I don’t know if it’s infected or what, because I don’t look at it. When I shower I only look up. I got used to doing this from the age of eight. Just let the water flow over it, and hope the toothpaste goes away.

Every time I think about taking it out I can’t breathe so I don’t think about that anymore. I just wear the right clothes and cover my tummy with a pillow or something if I can.

I’m going to change this top. It’s tight, it’s rubbing.

Yeah, I’d say that’s the crux of it. Why netball happened.

*

I’d been home several months when Asha gave me ‘the present’. It had been quiet and nice. Mum and Dad were cool to be around; they were wanting to be happy. Then a couple of weeks after my birthday Asha turned up with a tag on her ankle, and everything changed. We all tried to be positive to begin with, signing her ankle tag and drawing wee pictures on it. We all felt so sorry for Poor Asha, for whom everything appeared to have gone wrong. But pity and positivity were overshadowed by Asha’s anger and drinking, and by Mum’s depression and drinking, and by Dad’s constant absence even when he was present. If my thing is infected I reckon it happened the minute Asha walked in the door with that ankle tag on.

Camille Camille Camille Camille.

Sorry about that. Asha asked what I was writing that was making my face so slappable, so I upped the speed and intensity – I can write my name really fast, it’s the thing I’ve written the most I spose.

The therapist said this would help but it’s not. She’s like the Queen of England: bright red lipstick, pointless and nearly dead. She didn’t say what it might help with, and that’s because I don’t think The Queen knows anything.

You, Dear Diary, have been on my dresser since I was thirteen, stupid floral thing that you are. Asha pretended the tiny key must have gone missing when she was wrapping you – she went all manic making out like she was so upset; screaming that it must have got mixed up with the expensive dotty paper she bought at Northland and which I shouldn’t have torn because she was wanting to use it again for Anj McLean’s sixteenth birthday party. I knew then she stole the key. I didn’t try to find it, but I did keep you visible and accessible at all times and – as predicted – she has snooped regularly since. I know this because your first page is dog-eared and I haven’t opened you for eight years.

Mum eventually agreed that family therapy was a good idea after the netball injury. She’s always delegated to the professionals, and they have always backed her up, and that is exactly what happened. It took such courage to say what I said, finally out loud and in front of a non-Moloney-Singh, but no-one said a thing, not a thing. I rarely fight back with Asha and that’s why: because I never win. ‘I think we’re here because she broke my fucking nose,’ I said, and ‘fucking’ was all anyone heard even though swearing has always been an okay thing to do in this house. Not when The Queen of England is present, obvs, when she is present we have to pretend we all play polo.

I had to stop myself from bawling. I had to sit there and hold my shaking knees in place while The Queen set tasks that would help everyone but me, everyone but the girl with the broken nose.

Task no.1: move rooms, give ‘Poor Asha’ some space.

Task no.2: choose three family photos that depict happy times and bring them to next week’s session. (I am putting this off. I know it is going to get ugly. How, you wonder? Just you wait.)

Task no.3: is all about examining the ‘netball injury’ to ensure it does not happen again and I reckon I’ve nailed it – it all started when I was eight.

*