Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Collected Works

- Sprache: Englisch

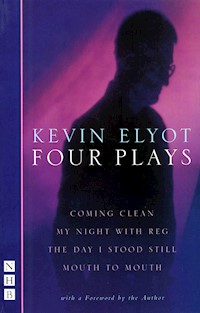

A collection of plays from the acclaimed author of My Night With Reg, spanning twenty years of work from a playwright who brilliantly captured the comedy of pain. Included in this volume are: Coming Clean (Bush Theatre, London, 1982), Elyot's first play, winner of the Samuel Beckett Award, an examination of infidelity within a gay relationship. 'A very funny and acute comedy about the gay life' Sunday Times. 'In time, it will be recognised as the first mature play about homosexuality' Mail on Sunday My Night With Reg (Royal Court Theatre, London, 1994) His breakthrough play, winner of the Evening Standard and Olivier Awards for Best Comedy, a heartbreaking play about the fragility of friendship, happiness and life itself. 'Sharply witty and humanely wise drama about gay manners and morals in the age of AIDS' Independent The Day I Stood Still (National Theatre, London, 1998) A poignantly funny drama about the heartbreak of unrequited love and the power of memories. 'What begins apparently as a very English comedy about avoiding the issue... ends as something both tragic and heartening' Sunday Times Mouth to Mouth (Royal Court Theatre, 2001) A brilliantly acerbic tragicomedy that transferred to the West End, starring Lindsay Duncan. 'An ingenious, brilliantly intricate work of art' Financial Times Also included is a foreword by the author. 'There is an unsentimental compassion about Elyot's writing that is deeply affecting, and a sharp observation of contemporary life that is often richly comic' Daily Telegraph 'Guilt, loss, unrequited love – these are the themes we've come to expect from Kevin Elyot' The Times

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 324

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Kevin Elyot

FOUR PLAYS

Coming Clean

My Night with Reg

The Day I Stood Still

Mouth to Mouth

With a Foreword by the Author

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword

COMING CLEAN

MY NIGHT WITH REG

THE DAY I STOOD STILL

MOUTH TO MOUTH

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

ForSebastian Born

Therefore: appear, shine, and, as it were, die.

Jean Genet, Letters to Roger Blin,translated by Richard Seaver

Foreword

The choir of St Peter’s in Handsworth, the Birmingham suburb where I spent my early years, consisted of a handful of grownups and myself. On certain Sundays we’d process through the streets with the vicar, carrying a cross, swinging incense and singing hymns. I was quite short at the time. Janet, one of the women, was fairly large. She had a childlike face, curly hair, a kind heart and a simple disposition. She’d regularly plonk herself down next to me in the vestry, both of us in cassock and surplus, and say, ‘Every picture tells a story.’ Then she’d laugh, and I’d smile, but I didn’t have a clue what she was talking about.

My parents often took my sister and me to the theatre: variety bills at the Hippodrome, where the number of the act would be displayed at the side of the stage, and pantomimes and plays at the Rep and the Alexandra. We had a family outing to Stratford when I was about ten to see a matinée of Richard the Third with Christopher Plummer and Eric Porter. That was the start of my love affair with the place: I’d do the hour’s journey on top of the 150 from Birmingham, queue for standing tickets and see shows two or three times. I was addicted, but it was St Peter’s that gave me my first fix.

*

For the briefest time I was taken into the confidence of Peggy Ramsay, the revered literary agent. In her office in Goodwin’s Court I perched on the sofa, where I fondly hoped Joe Orton had sat, and listened to the gossip and her occasional barbed opinions, sometimes of her own clients.

She’d taken me on after reading Coming Clean, my first foray into professional writing. From 1976 to 1984 I’d acted in several productions at the Bush Theatre, and Simon Stokes, one of the artistic directors, had casually suggested I try my hand at a play. I presented them with a script entitled Cosy, which was passed on to their literary manager Sebastian Born. He responded favourably and, largely through his support, it finally opened on 3 November 1982 under the title Coming Clean. Cosy had fallen out of favour – a pity, as I’d always liked the pun on the opera which plays such an important part. I came up with the present title as a necessary compromise after what had proved to be quite a bumpy ride from acceptance to premiere.

The Bush was the perfect space for David Hayman’s intensely intimate production, as Tony tried in vain to come to terms with his ‘open’ relationship with Greg. These were hedonistic times, when the worse that might happen, health-wise, was usually sorted by a trip to the clinic, where you’d pretend not to recognise each other, alarmingly aged in the cruel light of day, and when AIDS was a barely credible rumour filtering from across the Atlantic. The play’s final scene has an elegiac quality – in retrospect, almost a sense of foreboding. When Peggy saw it, she was in tears. ‘That’s the saddest thing I’ve ever seen,’ she said, disgorging the contents of her handbag on the floor. From then on, it was downhill.

‘lf you don’t write your next play soon, you’ll never write again,’ she warned. Alarmed, I forced out a piece called A Quick One. ‘Rather than write stuff like this,’ she said, ‘you should take up a hobby, like squash.’ Then I thought I’d try my hand at a radio play, According to Plan, which she insisted she wouldn’t be able to sell. I asked Sebastian Born, by now a literary agent with James Sharkey Associates, if he thought he might be able to sell it, which he did. It was transmitted in 1987 on Radio 4, directed by Pat Trueman, with Sheila Reid, Jean Anderson and Tom Wilkinson. Sebastian became my agent and the manuscript of A Quick One disappeared without trace.

I’ve yet to try my hand at squash.

A year after its London premiere there was a production of Coming Clean at the Palace Theatre, Westcliff. From the Leigh Times:

Let me say immediately that I did not enjoy this evening. In fact, it made me feel ill.

J. T. (theatre critic)

The play itself was a nasty, horrid little piece . . . Whatever happens to actors who have to perform such scenes night after night? . . . Do they spoil their own souls in order to divert us?

Councillor Joan Carlile, Southend

My family have attended the Palace Theatre . . . for thirty years, but not any more if this is the kind of beastly filth they are going to present us with . . . I consider Coming Clean to be a perverted horror.

David Price (letter to the editor)

*

One evening in the summer of 1993, alone in a house outside Todi, I thought, ‘So this is how it ends.’

The malaise had begun during what proved to be my last acting job – ironically, a tour of Molière’s The Hypochondriac. The gloom of fetching up in wintry, wet Worthing, or Swindon, or Poole, week after week in a fairly dismal show, was compounded by private fear as I obsessively weighed myself, wondering why the pounds were slowly shedding. By the summer, still refusing medical advice, I insisted on holidaying with friends in Umbria, where I spent most of the time in bed, high on fever and a diet of paracetamol. I even took some old antibiotics I’d come across, which brought me out in a fearful rash. My friends took me to a dermatologist, who, when he saw it, muttered, ‘Bestiale,’ and told me to take a blood test at the hospital in Todi. This I did with no intention of finding out the result.

The evening in question, I noticed a storm threatening on the horizon. It reached the house, cutting off the electricity, so I went outside to the fuse box, a pointless exercise even if I hadn’t had a fever. Back inside, huddled up on the sofa in the dark, I thought, for the first time in my life, that this was it. It wasn’t, but things would never be quite the same again.

Within days of getting home I was hospitalised with pneumonia. The love of family and friends, and the exceptional skill of Margaret Johnson and her team at the Royal Free, pulled me back from the brink – also, quietly but insistently, My Night with Reg, already scheduled for production the following year. Though I learnt later how close I was to snuffing it, I never once, after diagnosis, believed that I wouldn’t pull through. Since then I’ve clung to projects almost like fetishes to keep together body and soul.

My Night with Reg had been a long time coming. I thought of the title in 1983, but didn’t write it until nearly ten years later. In the meantime it started to emerge: a David Bowie concert I’d been to at Bristol’s Colston Hall in 1973; listening to ‘Every Breath You Take’ on the roof of an apartment block overlooking Central Park; the death of a dear friend and the funeral of another – gradually the pieces began to fall into place.

In 1991 it was commissioned by Hampstead Theatre. In 1993 they passed on it and Sebastian submitted it to the Royal Court. He got a swift response, and Stephen Daldry, in the process of taking the reins from Max Stafford-Clark, scheduled it for Easter 1994 in the Theatre Upstairs. He suggested Roger Michell should direct it, and our first meeting took place while I was still in the Royal Free. And so it moved forward, and I was determined to see it through. What seemed at times to be so nearly an ending proved, in fact, a beginning.

*

During the run of The Day I Stood Still at the National I got a card from someone I’d known at school, moved and disturbed to see parts of our story reconfigured on stage – but this was not the whole story. One summer’s afternoon, around the time of the death of Rolling Stone Brian Jones, I was enjoying an unlikely friendship with one of the school’s star sportsmen. He suddenly asked if I’d ever read James Baldwin, and for some reason I didn’t pursue his line of enquiry, a decision I regret to this day. Thirty years on, this tickled my imagination, and these and other little histories amalgamated in a fiction to the point where the play hardly accords with any actual fact. The past stalks the characters at every turn, so deftly achieved in Ian Rickson’s production that the ghosts onstage seemed at times to drift across the footlights. On a couple of occasions people told me they’d been convinced they’d seen their first lovers sitting in the audience.

Ideas can come from unexpected quarters. A visit with a friend one Sunday morning in August 1997 to Seville’s Hospital de la Caridad, where we saw Valdes Leal’s ‘Fin de la Gloria del Mundo’, then going back to the hotel and catching a news bulletin announcing Princess Diana’s death, somehow transmogrified a few years later into Mouth to Mouth, which is not about Seville, Valdes Leal or Diana. Mouth to Mouth was the second time I’d worked with Ian Rickson, and the first time I’d written a part for a particular actor: Lindsay Duncan. Old friends from Birmingham, it was, in a way, a testament to teenage aspirations.

After the purdah of writing, it’s always something of a treat to work again with actors, but any bonding is usually tempered with reserve, like being let back into the playground, but not back into the gang. Their commitment never ceases to amaze, none more so than the cast of Mouth to Mouth, led by Lindsay and Michael Maloney, at both the Royal Court and the Albery.

Once it had opened in the West End, a transfer plagued with difficulties, I went to Rome where I came across Magritte’s ‘L’Empire des lumières’ at a Surrealist exhibition, which set me thinking about a new play.

Another picture, another story, and a faint echo down the years of Janet in the vestry . . .

At the time of writing, Forty Winks is due to start rehearsals at the Royal Court, directed by Katie Mitchell.

Kevin Elyot

August 2004

COMING CLEAN

For

Jack Babuscio(1937-1990)

Coming Clean was first performed at the Bush Theatre, London, on 3 November 1982. The cast was as follows:

TONY

Eamon Boland

WILLIAM

C. J. Allen

GREG

Philip Donaghy

ROBERT

Ian McCurrach

JÜRGEN

Clive Mantle

Director David Hayman

Designer Saul Radomsky

Lighting Designers Bart Cossee and Simon Stokes

Characters

TONY, thirty-three

WILLIAM, thirty-six

GREG, thirty-eight

ROBERT, twenty-five

JÜRGEN, thirty-eight

Setting

The living room of a first-floor flat in Kentish Town. The essentials are as follows: two doors – one leading to the hallway, bedrooms, bathroom, and front door; and one leading to the kitchen; hi-fi equipment and record shelves; a window looking down on to the street; a dining area; a drinks table; a side table; a sofa and various chairs. The atmosphere is sparse: it has the potential of being tasteful, but lacks the necessary care. It isn’t homely, and also not very clean or tidy.

The action takes place from April to October 1982.

SCENE ONE

The Adagio of Samuel Barber’s String Quartet begins playing. The house lights fade. As the stage lights come up on TONY and WILLIAM, the music fades. TONY is in a dressing gown, pulling on a pair of socks. WILLIAM (from Bradford) is rolling a cigarette. On a chair, in a pile, are a pair of jeans and a shirt. A bag of doughnuts stands on the side table. Late morning.

TONY. Was it fun?

WILLIAM. No.

TONY. I’m surprised. He looked quite promising.

WILLIAM. I know.

TONY. Big, hairy, brutal, verging on the psychopathic. Just your type.

WILLIAM. That’s what I thought. But he wasn’t.

TONY. He looked like he ate babies for breakfast.

WILLIAM. He eats rusks for breakfast. Don’t let me hold you up.

TONY. I won’t. (He starts to pull on his jeans under his robe.)

WILLIAM. The lights in that disco’d put cosmetic surgeons out of business. I thought he was a virile forty, but in fact he’s a rather limp fifty. (He lights the cigarette.) And all those monosyllabic grunts he breathed down my ear in the club soon disappeared when we were sat in that taxi. Crystal-clear enunciation – Oxford English, a hundred per cent proof. And he wouldn’t shut up. He went on and on about some opera or other. I mean, I’d expected him to talk about lorry-driving, or hod-carrying, or oil rigs. But no – it was all legatos and top Cs! It’s not fair, is it? I thought I’d tricked with Steve McQueen, but I ended up with a leather-clad Richard Baker.

TONY. Steve McQueen’s dead.

WILLIAM. He’d still have been more fun.

TONY goes into the kitchen.

Honestly, Tony, I reckon some of these guys are contravening the Trade Descriptions Act.

TONY (off). What’s he do?

WILLIAM. Something in chemicals. He did explain it all to me, but it went in one ear and out the other. Like the rest of the rubbish he came out with.

He wanders over to the kitchen door to speak to TONY.

Mind you, he’s obviously well-off. More money than taste. His flat’s horrendous. An emetic combination of Salvador Dali and the Ideal Home Exhibition. Gallons of dark-blue paint everywhere, with hundreds of mirrors, and glass-topped tables, and concealed lighting. He was so proud of his dimmer-switch. Kept readjusting it to get the mood just right. I nearly said, the only thing that’d improve this room’d be a power cut.

TONY enters with two mugs of coffee and a jug of milk.

TONY. I quite like the idea of dimmer-switches. (He puts the coffee and milk on the side table.)

WILLIAM. And you couldn’t move for all these statuettes of Michelangelo’s David. Everywhere you looked. There was an epidemic of them. And endless plants of every description leaping out at you from all directions. Like a Triffid attack. And the bedroom! I tell you, I was frightened of falling asleep in there in case I woke up embalmed.

TONY. I knew I shouldn’t have gone. I spent a fortune: ninety p for a pint of lager!

WILLIAM. No one was twisting your arm to drink six.

TONY. I felt so uncomfortable. It’s such an effort holding your stomach in for four hours. Black?

WILLIAM. Yes. With a drop of milk.

TONY. It’s a beautiful day. You ought to go for a walk. Get some fresh air.

WILLIAM. My lungs’d collapse from shock.

TONY. God, those windows . . . (He takes off his dressing-gown and puts on his shirt.)

WILLIAM. We didn’t get to bed till five – he wouldn’t stop talking – and when we did, it was the same old story: he rolled over as soon as we hit the sheets. Talking of which, I think he must have lost the instructions to his Hoovermatic, cos I’m here to tell you, they hadn’t seen the inside of it for weeks.

TONY. You fucked him?

WILLIAM. If only to shut him up, but it didn’t. He liked talking dirty. Well, that turns me on. Sometimes. But not when he sounds like a Radio Three announcer.

TONY. Did you enjoy it?

WILLIAM. Not at all. It was like slopping around in a bowl of custard. Loose? I expected to find half of London up there. Do you want a jammy doughnut?

TONY. No thank you . . . (He checks himself in a mirror.)

WILLIAM. It’s so disillusioning! All these men who give the impression of being such studs, when in fact they’re just big nellies who want to get poked. Anyway, I made up for it this morning. I met his lover.

TONY. He has a lover?

WILLIAM. Yes. He’d been out all night, whoring, and he came back while my number was in the shower. So I introduced myself.

TONY. How civilised.

WILLIAM. Yes – I blew him off. Very nice it was too, until we were interrupted. From the state of the sheets, I should have realised – that guy was going to take a quick shower!

TONY. Did he mind?

WILLIAM. He minded. God knows why. They both screw around, but when it’s under their noses – well! So fucking hypocritical! I don’t know why they put themselves about. They’d obviously be happier living together in a Wendy house, watching the roses grow round the door. So, while they were going at it cat and dog, I thought it prudent to make myself scarce, which I did, and I left without so much as a cup of instant.

TONY (looking at his watch). Christ, he’ll be here in a minute. (He starts tidying up: cushions, books, papers, ashtrays.)

WILLIAM. That’s what you’re paying him for!

TONY. We haven’t even met. I’ve got to make a reasonable impression.

WILLIAM. Cleaning up for a cleaner! It’s like wrapping up rubbish before chucking it in the bin.

TONY. He hasn’t definitely said yes. I don’t want to put him off.

WILLIAM. Well . . . So what happened to you after I’d gone?

TONY. Nothing.

WILLIAM. I might have guessed. You were on the brink of a sulk when I left.

TONY. Well, it developed into a major depression.

WILLIAM attacks a doughnut.

WILLIAM. What about the guy in the construction helmet?

TONY. He deigned to look at me once during the whole evening, and his expression made me feel about as attractive as an anthrax spore.

WILLIAM. There were others.

TONY. He was the only one I fancied. Anyway, you know what I’m like. When it comes to the crunch, I get facial paralysis. I can’t even smile, let alone speak. I’m not exactly the greatest cruiser in the world.

WILLIAM. Rubbish! I’ve told you before, all you need is that little glint in your eye and you could get anyone you wanted.

TONY. A little glint!

WILLIAM. Just a hint of a smile around the eyes.

TONY. A hint of a glint.

WILLIAM. That’s right.

TONY. Which I don’t have.

WILLIAM. Only when you’re not concentrating.

TONY. So how do I normally look?

WILLIAM. Fucking miserable.

TONY. Thanks a lot. William, don’t you think you ought to use a plate?

WILLIAM. I like men in construction helmets. As long as they don’t wear them in bed.

TONY. He did look good, didn’t he? So arrogant. God, he could’ve done anything he liked with me . . . I wish I could have met him at a dinner party or something, had a chat, got to know each other a bit. In that situation, I do far more justice to myself, rather than leaning against a bar, trying to look like Burt Reynolds. Glinting.

WILLIAM. So why do you carry on going?

TONY. Because it’s addictive.

WILLIAM. And you enjoy it.

TONY. Well . . . yes. Sometimes. Anyway, I don’t go that often.

WILLIAM. You don’t need to. I don’t think I’d go at all if I had Greg to fuck me every night.

TONY. He doesn’t fuck me every night. Not after five years.

WILLIAM. He could fuck me every night after ten years.

TONY. You’d soon get itchy feet. One-night stands don’t suddenly lose their appeal when you fall in love. The prospect of a new body’s always exciting. Mind you, it is a transitory excitement, and it doesn’t change my feelings for Greg.

WILLIAM. A transitory excitement . . . I saw this guy who looked so – terribly transitory, and he took me back to his place and gave me a transitory rogering on the carpet, and after we’d spent our lust all over the Axminster, we lay transitorily in each other’s arms, and he looked into my eyes and said, ‘How was it?’, and I looked back at him, somewhat sultrily, and said, ‘My God, that was – transitory!’

TONY. Have you ever considered sending your jaw on holiday?

WILLIAM. Five years! Who’d have thought it? A paragon of domestic bliss! A man, a flat, a car, and now – a houseboy!

TONY. He’s not a houseboy. He’s a cleaner. Actually, he’s not even a cleaner. He’s an actor.

WILLIAM. An actor! No wonder he’s a cleaner. I’ve yet to meet an actor who actually acts. And Greg hates actors.

TONY. We’re hiring him to clean, not perform. Whether Greg likes him or not is irrelevant. As long as he’s good at cleaning.

WILLIAM. I wonder if he’s good at acting.

TONY. Please try not to be too disgusting when he’s here. Not everyone wants to know about the workings of your insides – or other people’s insides, for that matter. (He looks at his watch.) He’s late. (He lights a cigarette.)

WILLIAM. So how are you going to celebrate your anniversary?

TONY. What?

WILLIAM. Your anniversary!

TONY. We haven’t talked about it.

WILLIAM. You’ve got to do something.

TONY. What can we do? Greg’s such a difficult sod. He hates parties, hates eating out –

WILLIAM. Hates paying for it. Tight-fisted bugger.

TONY. We could have dinner here, I suppose, but I’d end up having to do it all, and that’s not my idea of a celebration.

WILLIAM. I’ll cook for you.

TONY. I wouldn’t trust you with boiling the kettle.

The doorbell rings.

WILLIAM. It’s the slave.

TONY. William, please . . .

TONY goes into the hall. Sound of front door opening.

(Off.) Hello.

ROBERT (off). Hello. I’m Robert.

TONY (off). Tony. Pleased to meet you. Come on in.

Enter ROBERT and TONY.

This is William . . . and William, this is Robert.

ROBERT and WILLIAM shake hands.

WILLIAM. Hello.

ROBERT. Hello.

TONY. William’s a neighbour. Well, almost a neighbour. Often pops round. Sort of a – permanent fixture, really. Did you find it alright?

ROBERT. Yes. No trouble.

TONY. Would you like some coffee?

ROBERT. Thank you.

TONY. I’ll make a pot.

WILLIAM. A pot!

TONY. William.

WILLIAM. Yes?

TONY. Would you like some coffee?

WILLIAM. Yes, please.

TONY. I won’t be a minute. Do sit down. (He goes into the kitchen.)

WILLIAM. Make yourself at home.

ROBERT. Thank you.

ROBERT sits. WILLIAM starts a roll-up.

WILLIAM. Would you like a roll-up?

ROBERT. No thanks.

WILLIAM. Don’t you smoke?

ROBERT. Sometimes. I have the odd Silk Cut, but then only on social occasions.

WILLIAM. Strictly business, is it?

ROBERT. No . . . yes. I suppose it is.

WILLIAM. You don’t mind if I do, do you?

ROBERT. No. Not at all.

Pause.

WILLIAM. I used to smoke Silk Cut, but I found they made me very chesty. I used to wake up with a very tight feeling just here – (Pats chest.) – and I’d cough and cough, but it wouldn’t budge. Nothing’d come up.

ROBERT. Did you smoke a lot?

WILLIAM. About fifty. But then I decided to roll my own, cos I thought it’d make me smoke less.

ROBERT. And did it?

WILLIAM. No, but it’s shifted the phlegm. Now when I wake up and have a really good cough, it all comes up. Great gobfuls of the stuff. Much more satisfying than having it sit on your chest all day.

ROBERT. I’m afraid they’re too strong for me. Although they do have – quite a flavour.

WILLIAM. Yes. (Beat.) This stuff’s repulsive. Like rimming a camel. Not that I ever have, but I can imagine. I suppose I’m just a glutton for punishment. Do you want a jammy doughnut?

ROBERT. No thank you.

WILLIAM. Well, it’s there for the eating. Madam didn’t feel like it. She suffers very badly from morning sickness. I wish you would, cos I’ll only eat it if you don’t.

ROBERT. I’m really not hungry.

WILLIAM. I don’t blame you. They’re not very nice. I like the sort which are really squidgy, that you bite into and the jam squirts out all over the place, and drips down your chin, and gets everywhere. With these, you’re lucky if you find a pinprick in the middle.

Enter TONY. WILLIAM devours the doughnut.

TONY. It won’t be long. Are you alright?

ROBERT. Yes, thank you.

TONY. It’s quite a mess, as you can see. I’ll show you round in a minute. I’m afraid Greg and I have been pretty slack about it all. We’re both rather . . .

WILLIAM. Filthy.

TONY. We hate cleaning, and any that was done I did. I think Greg thinks flats clean themselves. And it’s all got a bit out of hand. So . . . I’ll just . . . (He returns to the kitchen.)

WILLIAM. Do you like cleaning?

ROBERT. Yes. Yes, I do.

WILLIAM. Mm. (Beat.) I don’t. I can always find something better to do.

ROBERT. It’s a case of having to. I need the money.

WILLIAM. Are you very domestic?

ROBERT. In other people’s houses. I think I’m quite good at it. I also do the occasional bit of cooking from time to time. All helps to bring in the cash.

WILLIAM. What else do you do for cash?

TONY enters with the coffee.

TONY. Here we are . . .

ROBERT. What do you do?

WILLIAM. I’m a proofreader for Yellow Pages.

TONY. Black?

ROBERT. White, please.

WILLIAM. I wish I could afford a cleaner. One day, I hope to live in Kentish Town. But for now, the lower reaches of Tufnell Park will have to suffice. (To ROBERT, about TONY.) He’s very grand, this one, y’know. He thinks he lives in an After Eight commercial.

TONY. White?

WILLIAM. Yes, please. Have you met Greg yet? Oh no, of course you wouldn’t have. You’ll like him . . . Robert. He’s very nice, very warm. A most gregarious, outgoing sort of a person. And generous to a fault, isn’t he, Tony?

ROBERT. Where’s the bathroom?

WILLIAM. You’re not sick, are you?

ROBERT. No. I want to pee.

TONY. It’s through there. On the right.

ROBERT. Thanks. (He exits into the hall.)

TONY. William . . .

WILLIAM. I’m off. I’ve got loads to do. And I want to get some sleep before tonight. I have to look rested and serene if I’m going to score. At the moment I feel like a bucket of horseshit.

TONY. Cruising again!

WILLIAM. Of course.

TONY. You never stop.

WILLIAM. Well, you know what it’s like. Once you’ve had a taste, you keep wanting more. Like Chinese food. Talking of which, I’ve thought of a brilliant solution to your anniversary problem. Equity’s answer to Mrs Beeton also hires himself out for dinner parties. And I’m sure he’s very cheap.

TONY. What makes you so sure you’d be invited anyway?

WILLIAM. To make up the numbers. As ever. The day I’m invited to a dinner party and find an odd number of guests, I’ll know I’m loved.

TONY. William, you are loved.

WILLIAM. You sweet thing!

They embrace.

I’ll buy you something really special for your anniversary.

TONY. There’s no need. Without you, there wouldn’t be one.

WILLIAM. Oh! D’you know, I think I could fall in love with you, if I didn’t find you so sexually uninteresting.

TONY. You break my heart.

They kiss affectionately. Enter ROBERT.

ROBERT. Oh sorry . . .

WILLIAM. That’s alright. I’m just saying goodbye. Lovely meeting you, Robert. I’m sure we’ll meet again.

ROBERT. Yes. Goodbye.

WILLIAM. Tara, Tony. I’ll see myself out.

TONY. Bye.

WILLIAM exits. Sound of front door opening and then shutting. Pause.

So.

ROBERT. So.

They smile.

TONY. I’ll show you round, shall I?

ROBERT. Yes. (Beat.) I like your stereo.

TONY. Good, isn’t it?

ROBERT. I’ve always wanted one like this.

TONY. I’ll play something, if you like.

Beat.

ROBERT. Shall we get the business out of the way first?

TONY. Okay.

ROBERT. Where’s Greg?

TONY. At a conference. For the weekend.

ROBERT. Oh.

Beat.

TONY. After you.

ROBERT notices something behind the sofa. He picks it up. It’s TONY’s dressing-gown. He offers it to TONY.

(Taking it.) You don’t waste any time, do you?

ROBERT. Oh sorry . . .

TONY. No, no. I’m impressed. Shall we . . . ?

ROBERT. Yes.

ROBERT goes into the hall, as TONY holds the door for him. As TONY exits, he throws the dressing gown across his shoulder.

SCENE TWO

Morning. A vacuum cleaner is heard offstage. GREG (from New York) is reading through a manuscript, trying hard to concentrate. Eventually he looks up and sighs with frustration. He sits back. After several seconds the vacuuming stops. With relief, GREG returns to the manuscript. He begins annotating. The vacuum starts up again. GREG buries his face in his hands, then he composes himself, puts his hands over his ears and attempts to resume his work. The vacuum gets closer. Soon the door opens and ROBERT appears, pushing the vacuum cleaner, covering every square inch of carpet with concentrated thoroughness. He doesn’t seem to be aware of GREG. GREG has sat back from his work and fixes a beady eye on ROBERT.

GREG. Excuse me.

ROBERT doesn’t hear.

Excuse me.

ROBERT looks across, smiles shyly and continues his vacuuming.

Hey!

ROBERT looks across and turns off the cleaner.

ROBERT. Sorry?

GREG. Would you mind?

ROBERT looks slightly puzzled.

I am trying to work.

ROBERT. Oh. I’m so sorry. I wasn’t thinking.

GREG. Do you have to use that thing?

ROBERT. Oh . . .

GREG. Couldn’t you do something else? Elsewhere?

ROBERT. I’ve only got this room left to do.

GREG. Well, is there anything you could do that doesn’t involve noise?

ROBERT. I should think so.

GREG. I don’t wanna be difficult, but I’m finding it totally impossible to concentrate.

ROBERT. I’m so sorry.

GREG. There’s no need to be sorry. You’re doing your job. The only problem is I’m trying to do my job too.

ROBERT. I could do the dusting.

GREG. Yeah. Do the dusting.

ROBERT. Would that put you off?

GREG. No. That would not put me off. Dusting’s fine. (Beat.) So long as it’s not loud.

GREG has returned to his manuscript and ROBERT pushes out the vacuum cleaner. He returns with a duster and starts dusting. After a while, he stops, wanting to say something.

ROBERT. I’m sorry to bother you again but . . . are you going to be here for the rest of the morning?

GREG. If that’s alright with you.

ROBERT. Yes of course, but I was just wondering when I could do the vacuuming.

GREG. Next week. (GREG is still working.)

ROBERT. Okay. (ROBERT dusts.)

GREG. I’m sure the carpet will survive.

They continue working. ROBERT stops and looks across at GREG. He’s about to speak, then thinks better of it. He continues dusting. He stops again and plucks up the courage.

ROBERT. Would you mind if I interrupted again?

GREG. What is it?

ROBERT. Well, I just wanted to say how pleased I am to have met you at last.

GREG. Uh-huh.

ROBERT. Because I’ve read your book . . . quite a while ago, actually, and I enjoyed it very much.

GREG. Thanks.

ROBERT. It meant a lot to me.

GREG. Yeah?

ROBERT. You see, I come from Shrewsbury.

GREG looks blankly.

Have you ever been?

GREG. No.

ROBERT. I don’t recommend it; it’s very dull. I lived there until I was eighteen, and nothing goes on there, nothing at all, and I found it very difficult – being gay. In fact, I began to think that I was the only gay in the country, let alone Shrewsbury. But your book made me realise I wasn’t. It gave me a bit of confidence. It really helped.

GREG. Good.

ROBERT. Never looked back since.

Pause. He returns to his dusting.

GREG. You’re an actor.

ROBERT. Yes.

GREG. Ever work?

ROBERT. Oh yes. But it’s a bit of a bad time at the moment.

GREG. From what I understand, it always seems to be a bit of a bad time.

ROBERT. I suppose so.

GREG. Dunno how you do it.

ROBERT. It can be difficult.

GREG. Ever done television?

ROBERT. Oh yes.

GREG. What?

ROBERT. Bits and pieces. Nothing very much.

GREG. You work mainly in theatre?

ROBERT. Well, that’s where the opportunities have presented themselves, so far. Do you go much?

GREG. No. I prefer the movies.

ROBERT. So do I.

GREG. Uh-huh.

GREG returns to the manuscript. ROBERT dusts. Pause.

ROBERT. You’re from New York, aren’t you?

GREG. Yes.

ROBERT. I’ve always wanted to go there.

GREG. What’s stopping you?

ROBERT. Don’t know. Money?

GREG. You should go. It’s very exciting. I love it.

Beat.

ROBERT. Why do you live here then?

GREG. Well, when I’m in London, I sometimes wonder why I don’t live in New York, and when I’m in New York, I realise why I live in London. (Beat.) My work’s here. And of course Tony.

ROBERT. Do you go back much?

GREG. Once a year.

ROBERT. Tony’s very excited about the autumn.

GREG. Yeah. It’ll be his first visit. I’m looking forward to it.

ROBERT. I really must get it together. One day.

Beat. He returns to his dusting.

GREG. Hey, I tell you what?

ROBERT. What’s that?

GREG. Why don’t you leave that?

ROBERT. I’ve hardly started.

GREG. I can’t concentrate with you here. I’ve gotta get this finished. It’s already overdue. (Beat.) Leave it till next time, yeah?

ROBERT. Okay.

GREG continues working. ROBERT goes out and returns, minus the duster.

I’ll be going then.

GREG. So long, Richard.

ROBERT. Robert . . . actually.

GREG looks up.

GREG. Then so long, Robert.

Beat.

ROBERT. Tony said you’d have my money.

Pause.

GREG. How much?

ROBERT. Ten pounds.

Beat. GREG takes out his wallet and hands him ten pounds.

Thank you.

ROBERT moves to the door.

Bye then.

GREG (working). Goodbye.

ROBERT pauses at the door.

ROBERT. I’m sorry if I’ve been a nuisance, but I didn’t expect you to be here. Tony said you usually . . .

The phone rings. GREG lifts the receiver.

GREG. Hello? . . . Hi . . . I dunno . . . About six, I should think . . . Uh-huh . . . So-so . . .

ROBERT has gone out.

You wanna word with him?

GREG looks up.

Well, he just . . . hang on . . . (Shouts.) Robert?

Sound of front door shutting.

He’s gone . . . Just now . . . No, I’m not running after him . . . Can’t it wait? . . . What the hell do you wanna say to him anyway? . . . I’m sorry . . . Look, I really gotta get on, okay? . . . Yeah . . . See you.

He replaces the receiver. Beat. He returns to the manuscript. Pause. He suddenly throws down his pen.

Twenty dollars!

The Adagio of Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto starts playing.

SCENE THREE

As the lights come up, the music transfers to the speakers onstage. Evening. TONY, GREG and ROBERT are sitting round the dinner table. They have eaten the main course. They are drinking wine. TONY is smoking. There is an empty, untouched place set for dinner.

GREG. They’re so damned lazy. It’s like banging my head against a brick wall. I have to constantly nag to get any work out of them, and when they do get round to handing in an essay, it’s like they’re doing me a favour, even though it is six months late. And nine times out of ten, the standard is dismal, so I lose my temper, and then they sulk. They’re nice enough kids, but I don’t understand why most of them are doing the course.

ROBERT. I could never teach.

GREG. I can’t tell you how depressing it is standing in front of my classes. They’re like the Living Dead, or the Stepford Wives. They just sit there, blankly.

TONY. Maybe you bore the shit out of them.

GREG. I am never boring. I put a lot into it. I just wish they’d give me a little bit back.

ROBERT. It sounds very frustrating.

GREG. I’ve even resorted to jokes to try and get a reaction, but will they laugh?! Not a glimmer.

TONY. That’s because you’re not funny.

GREG. Thanks a lot.

ROBERT. What jokes do you tell them?

TONY. He only knows one.

ROBERT. I can never remember them.

TONY. Why don’t you tell it, Greg? We could do with a good belly laugh.

GREG. I’m not telling it now.

TONY. Go on. Robert wants to hear it.

GREG. You won’t find it funny.

TONY. I haven’t the past fifty times, it’s true, but –

ROBERT. I haven’t heard it.

TONY. We promise we’ll laugh, however badly you tell it. Won’t we, Robert?

ROBERT. Yes.

TONY. Go on.

Beat.

GREG. Well, do you know anything about American history?

ROBERT. Bits.

GREG. Like you know the names of the presidents?

ROBERT. Some of them.

GREG. Does Calvin Coolidge mean anything to you?

ROBERT. A little.

GREG. Well, he was president during the twenties. And it’s quite interesting that he should have been because the twenties were, culturally speaking, a very exciting, flamboyant decade, and Coolidge was anything but exciting and flamboyant. He kept himself very much to himself. And he was a pretty straight sort of a guy, a traditionalist, and he believed very strongly in the American way of life.

TONY. It’s the way you tell ’em!

GREG. If you don’t know fuck all about Coolidge, the joke doesn’t mean anything!

ROBERT. Please. Carry on.

GREG. Anyway, d’you know who Dorothy Parker was?

TONY. Greg! He’s not stupid.

GREG. Listen, one of my students thought she was a tights manufacturer.

TONY. Please tell the joke. The tension’s killing me.

GREG. Well, the day Coolidge died, some guy came up to her and said, ‘Have you heard the news? Calvin Coolidge has died – ’

ROBERT. Oh, and she said, ‘How can they tell?’ (Beat.) Is that the one?

TONY. ’Fraid so.

ROBERT. Sorry.

TONY goes to the stereo.

TONY. Any requests?

ROBERT. Shall I serve the pudding?

TONY. In a minute.

ROBERT. That’s dreadful of me.

TONY. Greg. What would you like?

GREG. Whatever.

TONY looks through the records.

TONY. Well, let me see. There’s Telemann, Vivaldi, Handel, Corelli, Bach, Village People. You’d like some Village People, wouldn’t you, Greg? You’re not going to sulk, are you?

ROBERT. I’m so sorry.

GREG. I’m not sulking.

TONY. Or we could even have some more Mozart.

ROBERT. We could hear the end of that concerto.

TONY. I think we’ve heard the best of that. I’m a sucker for slow movements. (He takes a record out of its sleeve.) More Mozart, I’m afraid. But this one’s an andante rather than an adagio. I hope you don’t find it depressing.

ROBERT. Oh no. I love Mozart.

TONY (putting record on the turntable). I have to admit, I am indulging myself. I’m suffering from that well-known after-dinner complaint: Melancholia Hirondelle.

He places the stylus on the disc: the Andante of Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante in E flat (K. 364).

ROBERT. What is this?

TONY. It’s here.

He hands the sleeve to ROBERT and points.

That one.

ROBERT. Oh. I haven’t heard this before.

TONY. I quite like it. There’s a lovely bit that comes up in a minute. A sort of descending – tune, that . . . Anyway, you’ll hear it.

He walks behind GREG and kisses his head.

Alright?

GREG. Uh-huh.

Beat.

TONY. Well, you could have chosen something.

GREG. I’m okay.

Beat.

ROBERT. When I was at school, there was this master who . . . took me under his wing, you might say. I don’t think he was gay, but his interest in me was more than academic. Anyway, I used to write a lot – poetry and things – and one day, I remember, he called me to his room and worked his way through a whole load of stuff I’d given him, line by line, word by word, until he’d completely eroded my confidence, and at the time, I – Sorry, are you listening to the music?

TONY. No. Carry on.