20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

From Scafell's towering volcanic crags to the deep lake-filled glacial valleys of Wasdale and Buttermere, the Lake District possesses an extraordinary variety of scenery in a relatively small area. This dramatic landscape has inspired writers, climbers, painters, and all who seek the solitude and beauty of the high fells – and wish to understand the forces that have shaped this unique place. With over 230 illustrations including maps and superb photographs with unique aerial views and panoramas, it includes: easy-to-understand explanations of how the rocks formed; how the geology affects the landscape and an exploration of the long human story of Lakeland landscapes. There are guided excursions to seven easily accessible geological locations and a dedicated website, with a Google Earth photographic guide to all the main localities mentioned in the book: lakedistrictgeology.co.uk This book will enable you to 'read' the landscape, understand how the region's rocks were formed, how glaciers and rivers sculpted the fells and valleys, and how human interaction with geology and climate has helped to create the Lake District today.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 295

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

The Lake District

LANDSCAPE AND GEOLOGY

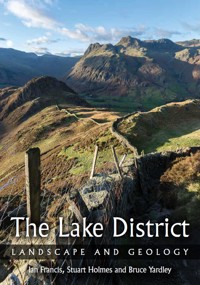

Sphinx Rock, a crag high on Great Gable near the western edge of the Scafell volcanic caldera, looking southwest over the deep glaciated trough of Wasdale.

The Lake District

LANDSCAPE AND GEOLOGY

Ian Francis, Stuart Holmes and Bruce Yardley

First published in 2022 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2022

© Ian Francis, Stuart Holmes and Bruce Yardley 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 71984 012 8

Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the many people who have helped in various ways, in particular Peter Knight (University of Keele), Hugh Tuffen (University of Lancaster), and David Breeze OBE, all of whom read and commented on sections of the book. Joe Murphy (Cumbria Wildlife Trust), Lois Mansfield (University of Cumbria), John Lackie (Cumbria GeoConservation) and David Harper (University of Durham) gave valuable advice. Richard Fox (Fix the Fells) provided text and images for parts of Chapter 10, and the artist Julian Heaton-Cooper provided text and kindly allowed reproduction of four of his paintings in Chapter 6. Thanks are also due to Kelly Davis, whose editing skills improved the manuscript enormously. Bruce Yardley would also like to thank Joe Cann, Alan Smith and the late Murray Mitchell for their introductions to various aspects of Lake District geology.

Front cover: Lingmoor Fell and Side Pike, looking towards the Langdale Pikes.

Cover design by Maggie Mellett

Contents

Natural Forces

1 Birth of the Lake District

2 Sculpting the Landscape with Ice

3 Sculpting the Landscape with Water

4 Time Travel

5 Making Lakeland’s Rocks

6 Geology and Scenery

Humans, Geology and Landscape

7 The Prehistoric Landscape

8 Wool, Walls and Wood

9 From Crags to Riches

10 Protecting a Fragile Landscape

The Excursions

1 Eycott Hill Nature Reserve

2 The Skiddaw Granite in Sinen Gill

3 Volcanic Rocks in Seathwaite

4 Coniston Copper Mines

5 Beatrix Potter’s Silurian Country

6 Around Tarn Hows

7 Limestone Landscape at Whitbarrow Scar

Further Reading

Image Credits

Index

CHAPTER 1

Birth of the Lake District

A remarkable interaction between geology, climate and human activity has produced some of the world’s most glorious scenery in the fells and valleys of this corner of northwest England. The 2362 square kilometres of the National Park boast England’s highest mountain, its largest lake and many of its most dramatic landscapes.

The Lake District. The white line of the National Park boundary encloses the high fells and lakes of Cumbria.

Today, Lakeland attracts millions of visitors every year, but until the mid-eighteenth century no sensible person would have chosen to go there for pleasure or recreation. Most considered it a remote and intimidating wasteland, a view expressed by Daniel Defoe in 1724:

Westmorland, eminent only for being the wildest, most barren and frightful of any that I have passed over in England … bounded by a chain of almost impassable mountains, which in the language of the country are called Fells.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, perspectives shifted as ideas of the ‘picturesque’ took hold in the popular imagination. The Lakes began to attract writers and artists, who were thrilled and inspired by the wildness of the mountain scenery and captivated by the dramatic juxtaposition of ‘frightful’ crags with the pastoral tranquillity of the valleys and lakes.

Early geologists

While the Lake District played a unique part in the development of the Romantic imagination, it also attracted a new sort of adventurer — geologists who classified the region’s rocks and minerals, and who sought to understand the processes that had created its remarkable landscape. The region produced its own pioneers in the field, notably Jonathan Otley (born in Grasmere in 1766 and later a resident of Keswick) and the illustrious Adam Sedgwick (born in Dent), who became Woodwardian Professor of Geology at the University of Cambridge. Sedgwick and Otley first met in 1823, and they remained friends and geological collaborators until Otley’s death in 1856.

In 1820, Otley published a short letter relating to his findings in a rather obscure Cumbrian journal known as The Lonsdale Magazine. Entitled ‘On the Succession of the Rocks in the District of the Lakes’, it was reproduced later that year in the more widely read Philosophic Magazine. In it, Otley described for the first time the three distinct belts of rock that underlie the Lake District, and their relative ages.

He observed that the first, and lowest, in the series ‘forms the mountains Skiddaw, Saddleback, Grisedale Pike and Grasmoor, with most of the Newlands mountains… All the rocks of this division are of a dark colour, inclining to black, and generally of a slaty structure’. Otley called these rocks ‘Clayslates’. Next, he identified what he called the ‘Greenstones’:

Rocks more varied in their composition … generally of a pale bluish-grey colour. The mountains of Eskdale, Wasdale, Borrowdale, Langdale, Grasmere, Patterdale, Martindale, Mardale, etc including the highest mountains … are all in this division.

Last, he described ‘the third division’, which ‘[formed] only inferior elevations’. This belt ‘[commenced] with a bed of a dark blue limestone … succeeded by rocks of excellent flags … and dark-coloured roofing slate’. These rocks form the low country around Windermere and Coniston Water.

This was an era when amateurs could still make an important contribution to the young science of geology, and Otley’s recognition of the three-fold division of the region’s rocks was certainly crucial. For this insight (and his other observations on cleavage and bedding described in Chapter 5), he is rightly called the ‘father of Lakeland geology’.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, all discerning visitors to the region were expected to have at least some interest in its geology. Wordsworth included three long passages written by Adam Sedgwick in the 1842 edition of his famous Guide to the Lakes. These beautifully summarized what was then known about the region’s geology, and they are still worth reading today. Sedgwick observed that the high Cumbrian fells appear as a jumble of peaks and valleys markedly set apart from the more subdued hills that surround them:

By whatever line a good observer enters the region … he must be struck with the great contrast between the hills and mountains that are arranged on its outskirts, and those which rise up towards its centre. On the outskirts, the mountains have a dull outline, and a continual tendency to a tabular form: but those in the interior have a much more varied figure, and sometimes present outlines which are peaked, jagged, or serrated.

The rocks around the edges of the high fell country sometimes lie on top of Lakeland rocks, which are often hard and slaty, with some tilted or contorted layers. Sedgwick surmised that the Lake District rocks must be much older than those of the surrounding regions. By the time the younger rocks of the periphery were laid down, the older rocks were already, as he put it, ‘as hard and solid as they are at the present day’.

Modern dating techniques (seeChapter 4) have confirmed that the early geologists got it right. It is now known that the rocks making up the heart of the Lake District are between 400 and 485 million years old. By contrast, the rocks around the edges of the region are at least tens of millions of years younger.

Looking north to the Lakeland Fells from Scout Scar, Kendal. The viewpoint is a ridge of the Carboniferous limestone that underlies the Yorkshire Dales, but the older rocks of the Lake District emerge from beneath the limestone at the base of the cliff. Millions of years ago, the limestone extended across the entire region.

Jonathan Otley’s theory about the three-fold division of the rocks of the Lake District has also stood the test of time. His ‘Clayslates’ of the northern fells are now known as the Skiddaw Group (or, more informally, the Skiddaw slates). They are the oldest rocks in the region, formed from marine muds and silts, and found mainly in the fells between Keswick and Cockermouth (and in an isolated patch at Black Combe near Millom).

Resting on the Skiddaw slates, and therefore younger, are Otley’s ‘Greenstones’, now known as the Borrowdale Volcanic Group (or simply the Borrowdale volcanics). These are mainly lava and ash, erupted from long-gone volcanoes. Since the rock layers incline to the south overall, the Borrowdale volcanics are found to the south of the Skiddaw slates, forming the high central and eastern fells.

South of the central fells, the volcanic rocks are overlain by marine mudstones and sandstones belonging to the Windermere Supergroup (known as the Windermere group for simplicity). These mudstones and sandstones lie beneath the southern Lake District.

Thornton Force in the Yorkshire Dales. The lip of the fall is formed from layers of grey Carboniferous limestone. Below these limestone layers are revealed much older brown-coloured rocks, comparable to the slates and sandstones of the Lake District.

Many of the sediments that gave rise to the rocks of all three of the main divisions originally contained clays, and have been converted to slates by being deeply buried and squeezed during large-scale earth movements in the distant past. Slates are therefore common in all three of the main divisions of Lakeland rocks, and have been of great importance in the economy of the region. (The origin of slates is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.)

Both Otley and Sedgwick recognized a fourth category: granites. These formed when molten rock created deep within the crust rose upwards, forcing its way into the other rock groups. The two main areas of granite are around Eskdale in the southwest, and between Ennerdale and Buttermere. Smaller outcrops occur near Skiddaw and Shap.

The mountainous Lake District

The Lake District is often referred to as being ‘mountainous’, but this does not refer only to its height. The Lake District fells are indeed high by English standards, but not exceptionally so. Cross Fell in the northern Pennines rises to 893m - higher than all but a handful of Lakeland fells - and the Pennines as a whole have a greater area of land over 600m. ‘Mountainous’ in this context means that the Lake District fells share many characteristics with major mountain ranges - steep slopes, deep valleys, rocky peaks, and so on - but on a small scale.

Why is this? Well, a superficial answer might be that the Lake District rocks are harder than those surrounding them, and so they have resisted erosion. Like many simple answers, this has some foundation in truth, but fails to get to the heart of the matter. The gentle landscape surrounding the Lake District is certainly formed from younger rocks, but it is debatable whether they are particularly soft and easily eroded. The red sandstones of the Eden valley and the Solway coast are hard enough to make excellent building stones, for example, while the limestones and sandstones that extend east to the Pennines give rise to extensive high plateaux, including Cross Fell.

A more accurate answer might be that, over geological time, the area has actually risen up, relative to its surroundings. Rocks like those of the Lake District are in fact present below much of England but they are normally hidden hundreds of metres below the surface. There is plenty of evidence to support this version of events. For instance, in some places at the edge of the National Park, such as Scout Scar, younger rocks clearly sit on top of much older ones. The same relationship is seen further east, in the deep valley bottom of the Ingleton Waterfalls Walk, off the A65 in the Yorkshire Dales. Here, erosion has cut down through the overlying limestone to reveal more ancient rocks, very like those seen in the Lake District.

So it is likely that limestones (like those of the Pennines), and other sedimentary rocks, were originally deposited above the rocks of the present-day Lake District. They were then removed by erosion, not because they were particularly soft, but because earth movements lifted up the Lake District relative to surrounding areas.

Geological map of the Lake District, showing the location of the described excursions. The old rocks of the Lake District form three distinct northeast-southwest bands, with the younger rocks in a ring around them.

Cumbria from space (ESA Sentinel 2 image, June 2020). Skiddaw Group and Borrowdale Volcanic Group rocks underlie the light brown areas (the high fells), contrasting with the dark greens of the southern Lakes around Windermere, underlain by Windermere group rocks, where the landscape is gentler, and well wooded. Encircling much of the Lake District is a light green patchwork of fields marking the richest agricultural land in the county, underlain by much younger rocks. The Scafell range is in the very centre of the image and radiating outwards from the fells are the principal valleys of the Lake District.

A much simplified north-south geological cross-section through Cumbria, to show how Permian, Triassic and Carboniferous rocks have been stripped away from the uplifted dome of older rocks that form the Lake District fells. The vertical scale is greatly exaggerated.

To better understand this uplift, it might help to imagine the Lake District as a cake sliced down the middle, revealing its different layers. This imaginary cross-section reveals the way in which the three main divisions of hard ancient rock, and the granites, which together form the Lakeland fells, have been pushed up. The younger rocks, which once covered the entire region, have been stripped away from this uplifted central area so that they are found only on its peripheries.

How and when did this uplift occur? Between about 90 and 65 million years ago, in what is known as the Cretaceous period, most of the British Isles was covered by a clear, shallow sea. Microscopic shells accumulating on the seabed became a distinctive limestone, the Chalk. The Chalk Sea almost certainly extended across what is now the Lake District, because this limestone is found to the east in Yorkshire and to the west in Northern Ireland.

Sixty million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous, the North Atlantic began to open, separating northwest Europe from North America. This was a time of volcanic activity to the west and north of the Lake District (from the Hebrides, south to Antrim); the western skies would have glowed red at night from the outpourings of lava over the horizon. These Earth movements caused the crust near the new Atlantic margin to break up along lines of weakness (known as faults). Rocks were tilted and some regions were forced up, relative to others. The Lake District was one such region: a chunk (or ‘block’) of the Earth’s crust, bounded by fault lines and pushed upwards along them.

The principal rivers of the Lake District (adapted from Mill’s Bathymetrical Survey of the English lakes, 1895). The rivers follow the drainage pattern originally created on a domed upland that formed 60 million years ago, as the region emerged from the sea. Glacial erosion during the Ice Age accentuated the valleys to produce deep troughs, some now occupied by lakes (in black).

As the Lake District steadily rose (at a rate of just a few millimetres a year), its surface was subjected to the inexorable forces of erosion. Over millions of years, the rivers carved their way downwards, first removing the chalk, then, successively, older layers of rock, until eventually the ancient rocks were exposed. At least a kilometre of rock has been removed from above the present-day fells since the uplift began, and probably more in some parts.

The radial distribution of rivers, valleys and lakes in today’s Lake District probably reflects the original pattern of the streams that drained the chalk as it emerged from the sea. This period of uplift and erosion was the start of the development of the Lake District as we know it today, although it is still only poorly understood. It is likely, however, that the uplift was largely complete by around 25 million years ago.

Then, around 2.5 million years ago (at about the same time as our hominid ancestors started to use stone tools in Africa), the planet was plunged into its most recent Ice Age. Many periods of glaciation ensued, each lasting millennia, interrupted by shorter warm intervals when the ice retreated. During the cold episodes, glaciers moved down the original river valleys in the proto-Lake District and scoured them into deep, steep-sided troughs. Many of these glacial troughs are now occupied by the lakes that give the region its name.

In short, it is uplift of the Lake District that largely explains why its rocks are different from those found at the surface in surrounding areas. Nevertheless, as Chapter 5 will explore, Lakeland rocks and their hardness do affect landscape, and each of the major rock groups gives rise to distinctive scenery.

The Lake District landscape is, above all, glaciated. The next two chapters will explore how ice created the landscape, and how water continues to modify it.

CHAPTER 2

Sculpting the Landscape with Ice

Geologists now recognize several distinct episodes in our planet’s history when there has been extensive ice cover. Sometimes, the entire planet was encased in ice, while at other times even the poles were free of ice. The cold periods are known as Ice Ages.

Decades of scientific research, using cores sampled from polar ice caps, as well as other sources of long-term climate data, show that the Earth has been in an Ice Age for the last 2.5 million years. During this period there have been as many as 50 separate glacial periods, each interrupted by a shorter warm (or interglacial) interlude, such as the one we are in now.

Each glacial–interglacial cycle within an Ice Age takes approximately 100,000 years. Subtle but regular changes in Earth’s orbit which affect the amount of solar energy reaching the planet’s surface provide an astronomical explanation for the climatic changes needed to trigger the beginning and end of each glacial period.

It is impossible to determine how many of these 50 glacial episodes, or Stages, directly affected the Lake District, because glaciers erode away much of the evidence of previous glaciations. Geologists have found evidence for at least three glacial periods in Cumbria, but it is likely that there have been many more.

The Helvellyn ridge, here seen looking northwest with Thirlmere behind, is carved into a series of impressive cirques on its eastern side (to the right). The western side slopes to Thirlmere uninterrupted.

How do glaciers act on a landscape?

Glaciers are the most powerful agents of erosion on the planet. They erode by abrasion (where rocks carried along at the base of the ice stream act like sandpaper, grinding away at the land surface) and by ‘plucking’ (where boulders are prised away from the bedrock by mechanical force). Fast-flowing valley glaciers, such as those in the Alps or Himalayas, can remove on average 1–5mm of solid rock per year. Clearly, over the thousands of years of glacial erosion that the area has experienced since the current Ice Age began, there has been ample time for glaciers to carve the deep valleys that make the Lake District so spectacular.

Mosedale near Threlkeld. Thick deposits of glacial boulder clay like this are common around the edges of the Lake District.

Glaciers not only wear down the land surface; they also act as giant conveyor belts, carrying rocks, gravel and finer material from mountain areas into valleys and surrounding lowlands. This debris is dropped when the ice melts, to leave mounds or ridges (called moraines) in the valley floors, or sheets of glacial boulder clay (also referred to as ‘till’), which underlie much of lowland Cumbria.

Effects of glaciers in the Lake District

The most recent glacial period (called the Devensian Stage) started about 115,000 years ago, and ushered in what is known colloquially as ‘the last Ice Age’, which ended about 11,500 years ago. The coldest time in the Devensian was a relatively small part of the whole period – between about 25,000 and 14,000 years ago – when, as we will see, huge glaciers formed in the Lake District.

Before this period of maximum cold, the region’s climate was cool, rather than truly arctic, probably not that different from the conditions found in Iceland and northern Scandinavia today. The ground below the surface would have remained frozen all year round, with snow cover lingering into the summer. Small glaciers may have been present in the highest fells.

If we could travel back in time to this earlier Lake District, we would probably recognize many of the large-scale features of the landscape. After all, its valleys and fells had already been affected by earlier glacial periods in the more than 2 million years leading up to the Devensian.

At some point after about 30,000 years ago, rapid cooling set in, leading to a climate similar to that of today’s polar regions. One of the first signs of this change would have been the appearance of permanent snow patches on the higher slopes and valley heads, particularly those with a northerly or northeasterly aspect. As these areas received least sunlight, the snow blown into them by the prevailing southwesterly winds was allowed to accumulate.

As the snow built up year on year, it compressed under its own weight, and recrystallized into ice. Ice fields began to grow in the fells, and eventually the ice started to flow downhill under the influence of gravity, forming glaciers.

Small high-level glaciers like these lacked the erosive power of the huge valley glaciers that were to form later, but they were able, over millennia, to scour amphitheatre-shaped hollows in the fellsides. Physical geographers call these hollows cirques, but they are known in Cumbria as coves, coombes or combes; in Scotland, they are corries, and in Wales, cwms.

Cirques – and the tarns that lie in many of them – are perhaps the most instantly recognizable landscape features of the fells; tarns will be dealt with in more detail in Chapter 3. There are at least 150 cirques in Lakeland, the vast majority of which (around 125) are found in the Borrowdale volcanics of the central fells, with only around 28 in the Skiddaw Group fells to the north, and none in the Windermere group country of south Lakeland.

The Red Pike – High Stile ridge, here seen looking southeast towards Buttermere, exhibits several cirques on its northeastern flank (left, in the photo), in contrast with the smooth slopes on the Ennerdale valley side, to the southwest.

For the reasons noted above (wind direction and sunlight), Lake District cirques are mostly found on northern, northeasterly or easterly sides of the fells and not on west-facing slopes. The Ullswater side of Helvellyn, for example, boasts a spectacular group of cirques, whereas the western – Thirlmere – side of the ridge has none. The ridge between Red Pike and High Stile (Buttermere) shows a similar pattern: High Stile falls relatively smoothly down to Ennerdale, whilst on the opposite side the ramparts of Burtness Combe, Bleaberry Tarn Coombe, and Ling Combe (all examples of cirques) tower over the Buttermere valley.

Striding Edge, an arête on the south side of the Red Tarn cirque, Helvellyn.

Examples of U-shaped glaciated Lakeland valleys:TOPNewlands valley, near Keswick, looking north towards Skiddaw;BOTTOMEnnerdale, looking down-valley from Green Gable.

The glaciers in adjacent cirques eroded the mountain shoulders separating them, to produce narrow ridges called ‘arêtes’. The Lake District’s arêtes are not as narrow as those of the French Alps (from where the word originates), but fell-walkers are nevertheless well advised to treat Sharp Edge on Blencathra and Striding and Swirral Edges on Helvellyn with the respect they deserve.

Into the freezer – the glacial climax

As glacial conditions tightened their grip, so the cirque ice fields grew, and the small glaciers coalesced into larger valley glaciers. This process is evident in modern glaciated regions, of which the area to the east side of Sermiligaaq Fjord, in the southeastern corner of Greenland, is a fine example.

Ice from cirque glaciers flows out of the cirques and coalesces into a primary valley glacier on the east side of Greenland’s Sermiligaaq Fjord.

The first extensive valley glaciers in the Lake District probably formed in valleys such as Wasdale, Ennerdale and Eskdale. These radiate westwards and southwestwards from the highest fells in the centre of the region, where the most snow would have accumulated and been converted to ice. Within perhaps only a few centuries from the appearance of year-round cirque ice fields, all the Lakeland dales were occupied by glaciers. These continued the action of erosion that had begun in earlier glacial periods, carving the valleys, steepening their sides and widening the valley bottoms to create a characteristic U-shaped profile. These U-shaped valleys are found in all glaciated mountain regions worldwide, and they are an iconic feature of the Lake District landscape.

The thicker a glacier is, the faster it erodes the rock beneath, so the main valleys were deepened more rapidly than the tributary valleys, with their smaller, less powerful glaciers. This meant that the ends of the tributary valleys were eventually left ‘hanging’ above the main valleys, separated from them by a steep slope. Gillercomb hanging valley above Seathwaite (in the south of Borrowdale) is one example, but there are many more distributed throughout the Lake District.

Examples of ‘knock-and-lochan’ landscape produced by glacial scouring:TOPHigh Knott, Borrowdale (with Derwentwater and Skiddaw in the far distance);BOTTOMupper Eskdale, with the River Esk visible on the right (Scafell, Scafell Pike, Ill Crag, Esk Pike, and Bowfell form the mountain skyline).

The view west from Thorneythwaite Fell across Seathwaite, Borrowdale (Excursion 3). Sour Milk Gill tumbles down into Seathwaite from the lip of the hanging valley of Gillercomb.

Glaciers were most effective at grinding away the underlying bedrock about midway down their length. This is where the ice was thickest, and where it flowed most rapidly. Here, the valley bottoms were scooped into deep basins, often deeper than the downstream parts of the valley. As the ice retreated from the Lake District valleys, these basins filled with water to form the elongated lakes that are the defining feature of the region (seeChapter 3).

Erosion by ice was not confined to the valleys. Where the ice sheet built up across intervening fells, these too were scoured by flowing ice, which relentlessly wore away at weaknesses in the rock. This gave rise to a landscape of crowded rocky knolls, separated by shallow depressions; it is sometimes called a ‘knock-and-lochan’ landscape, after its Scottish counterpart. Good examples can be seen on Haystacks, above Buttermere, and around Eskdale.

Ice-free peaks?

During the 100,000 years of the Devensian Glacial Stage the severity of the climate and the thickness of the ice varied considerably. There is debate about whether the highest peaks – above about 800m – protruded above the ice, as ‘nunataks’, like those seen in Greenland and Svalbard today. The summits of Scafell, Helvellyn and Great Gable, for example, may have been free of thick ice for long periods.

Nunataks protrude through the ice sheet of southern Svalbard. Some geologists believe that Lakeland’s highest peaks were similarly ice-free for long periods during the Devensian glaciation.

This theory is supported by the rounded profiles of many summits in the highest fells, suggesting they may have suffered far less glacial erosion than the steep and rugged valley sides.

There is an alternative explanation though: perhaps these highest peaks were covered by ice, at least at times, but the ice was frozen to the ground surface, preventing the sort of erosion that took place under fast-flowing valley glaciers.

A brief thaw and the re-advance

Around 14,500 years ago, the climate in northern Britain suddenly warmed and, within as little as a decade, summer temperatures recovered to levels similar to those of today. This has been determined via the study of beetle remains and plant pollen preserved in lake-bottom muds. The ice retreated, first from the lowlands surrounding the Lake District, and from the south- and west-facing slopes of the fells. The glaciers stagnated, then retreated up-valley. Cumbria became ice-free for the first time in about 15,000 years. Vegetation returned to the valleys, and animals and their Mesolithic hunters ventured into the lowland forests.

The rounded summits of Lakeland’s highest peaks may have been ice-free for long periods. Looking east to the central fells, the nearest peak is Pillar; Great Gable lies at the head of Ennerdale (the valley on the left), while the Scafell range lies to the right of Gable.

However, the brief thaw did not quite mark the end of the glacial period. About 13,500 years ago, there was a sudden lurch back to colder conditions, a period known as the Younger Dryas (also sometimes called the Loch Lomond Re-Advance). Glaciers returned to the highest fells and the vegetation that had become established in the valleys disappeared.

One of the UK’s most spectacular fields of hummocky moraines lies at the head of Ennerdale. Black Sail YHA is just visible top centre.

The glaciers that re-grew in the high valley heads and cirques during the Younger Dryas left their mark in the form of moraines – piles of rock debris that were carried by the glaciers, then dumped on the valley floor and sides, either while the glaciers were active, or once they started to retreat. Most Lakeland valleys contain moraines of different shapes and sizes, and geologists have used them to map the likely extent and distribution of the Younger Dryas glaciers. Some of the most impressive moraines can be seen in the higher valley heads of the central fells. The moraine field at the head of Ennerdale, just beyond the Black Sail YHA hut, is a particularly spectacular hummocky example.

Long Combe, a cirque above Coledale, near Braithwaite, west of Keswick. Crescent-shaped moraines draped across the outer edge of the cirque mark the edge of the vanished cirque glacier.

Terminal or end-moraines were deposited at the snout (or terminus) of glaciers. They are often found at the edges of cirques, marking the position of the outer limit of a cirque glacier.

An erratic of Borrowdale lava, resting on Skiddaw slates 350m above sea level on Broom Fell, near Cockermouth. The boulder was carried by ice some 15km northwards, probably from the Honister area.

The maximum extent of the Devensian British-Irish Ice Sheet, about 25,000 years ago.

Patterns of ice flow in the landscape

At the height of the glacial period, some 25,000 years ago, all of Scotland, northern Ireland and most of northern England and Wales were glaciated. Although some Scottish ice flowed south, it never over-rode the Lake District. Instead, this area – because of its relative height and its high volumes of snowfall – was a glacial centre, with its own home-grown glaciers flowing radially outwards from the central fells and merging with the Scottish ice streams. We know this from the boulders and debris that the glaciers left behind.

One type of boulder is the erratic, made of rock gouged from valley sides and floors by glaciers, and carried by the moving ice, often ending up many miles from their point of origin. Only the hardest boulders survived this treatment, so most Lake District erratics are of Borrowdale volcanic rocks, or granite.

Boulders of these rocks from the central fells are found widely scattered in areas surrounding the Lake District, such as the Solway Plain, the Vale of Eden, Morecambe Bay and as far south as Cheshire. They prove that ice from the high central fells flowed westwards towards the Irish Sea, north towards the Solway Firth, east to the Vale of Eden and south to Morecambe Bay.

An erratic of Scottish granite exposed at low tide on the Solway coast near Maryport. The boulder was carried by ice from Criffel, 40km to the northwest and visible on the opposite shore. Scottish ice reached the coastal fringes of Cumbria but was prevented from continuing further inland by glaciers flowing outwards from the Lake District.

Ice flowing south from Scotland seems to have been deflected away from the Lake District towards the Solway and Irish Sea to the west and the Eden valley to the east. The evidence for this is that Scottish erratics (such as boulders of Criffel granite) are found in these peripheral areas, but never within the Lake District itself.

As well as indicating the direction of ice flow, erratic boulders also give clues about glacial thickness. Boulders are regularly found at heights of up to 800m or more in the Helvellyn range, for example, and occur on the summit of Whitbarrow (215m) in the far south of Cumbria (seeExcursion 7).

A drumlin field near Millholme, Kendal, looking west. Each of the low hills in the middle ground is a drumlin. The long axes of the drumlins run roughly northeast-southwest.

Another clue to the direction of ice flow comes from drumlins. These are small hills composed of glacial sand and gravel, moulded by moving ice. They usually occur in swarms, called drumlin fields, and are found in the lowlands surrounding the fells such as the Solway Plain or Eden Valley. Formed under ice sheets, their long axes run parallel to the direction of ice flow, and their elongated tails point ‘downstream’.

Entering the Lake District from the southwest, between the M6 motorway and Kendal, you drive through a rolling agricultural landscape, dominated by numerous drumlins. These rounded hillocks are elongated, with all their long axes running in the same general direction. Seen from the air, they look rather like a school of whales breaking the surface. The use of satellite and aerial photography to map drumlins has enabled geologists to reconstruct the directions taken by the principal glaciers, as they flowed out of the Lake District uplands, or southwards into Cumbria from Scotland. This information, combined with data from glacial erratics, gives an overview of ice flow directions in Cumbria.

Patterns of ice flow during the Devensian glaciation. The dashed line shows the approximate zone where Scottish and Irish Sea glaciers met ice moving west from the Lake District.

Flowing ice produced two other features in the Lakeland landscape: ‘roches moutonnées’ and striations. Roches moutonnées are distinctive rocky outcrops created when the moving base of a glacier encountered a band of particularly resistant rock. It rode over this obstacle, smoothing the side facing up-flow, but breaking up the leeward side by fracturing, then prising away fragments of rock. The rocky outcrops that resulted are smooth on one side, and craggy on the other. (The name was coined by the French eighteenth-century naturalist de Saussure, who saw a resemblance between the rocks shaped by this process and the wigs worn by French gentlemen at the time. These wigs were, apparently, called moutonnées